Fashions come and fashions go. Changes in clothing, automobiles and restaurants follow popular trends and are often periodic and cyclical. Ideally, medical change is driven not by fashion but instead by concepts of effectiveness and safety, and that these improve and refine as better data become available. Trends hold true also in anesthesia practice, where for example intraoperative opioid selection has swung from long-duration to ultra-short duration and then at least partially back again.1. Recent years have witnessed a new fashion in anesthesiology – “opioid-free anesthesia”. For some, the opioid pendulum has swung clear past rational opioid use in balanced anesthesia, to eliminating opioids intraoperatively and sometimes also postoperatively (“opioid-free analgesia”). Eradicating opioids from intraoperative and postoperative analgesic plans has been termed a “movement”,2 and like many “movements” it has attracted passionate proponents and spirited debate.3,4 Nevertheless, clinical research and peer-reviewed evidence on the potential benefits and risks of opioid-free anesthesia have remained scant, needed, and called for.5–7

This issue of Anesthesiology features two articles on opioid-free anesthesia, which bring some light to the heat of the debate. The original investigation by Beloeil et al reports the results of a randomized clinical trial of balanced anesthesia with either remifentanil or dexmedetomidine (opioid-free).8 The review by Shanthanna et al provides a narrative exposition of opioid-free versus opioid-sparing approaches in the perioperative period.9 These articles are timely and important.

The clinical trial8 was investigator-initiated, multicenter, randomized, prospective, parallel-group, and single-blind, conducted in 10 centers in France, with an independent data and safety monitoring board to oversee the conduct and review safety data. Patients undergoing major noncardiac surgery received intraoperative balanced anesthesia featuring opioids (remifentanil infusion and morphine) or dexmedetomidine infusion (opioid-free), and postoperative morphine. The primary outcome was a composite of opioid-related adverse events (hypoxemia, ileus or cognitive dysfunction) in the 48 hours postoperatively. Secondary outcomes included postoperative pain, opioid consumption, nausea and vomiting, and times to extubation and PACU discharge.

Frighteningly, the investigation was stopped prematurely, because of safety concerns. Specifically, there were 5 cases of severe bradycardia in the dexmedetomidine group, including 3 cases of asystole. The composite primary endpoint (adverse events) occurred in significantly more dexmedetomidine (78%) than opioid (68%) patients (relative risk 1.16), due to greater incidence of hypoxemia but not ileus or cognitive dysfunction. Times to extubation and PACU discharge were significantly longer in the dexmedetomidine than the opioid group. While dexmedetomidine patients had lower rates of nausea and vomiting, postoperative morphine consumption was statistically but not clinically meaningfully less (median 3 mg difference), and postoperative pain scores, ICU admission, and length of stay did not differ between groups. The authors concluded that balanced opioid-free anesthesia with dexmedetomidine increased serious adverse events and they questioned the benefit of eliminating intraoperative opioids in favor of dexmedetomidine.

This investigation is important, because it evaluated both the benefits and risks of an opioid-free anesthetic regimen in a carefully controlled and blinded randomized trial. Any benefits were negligible. It is rare and concerning when a clinical trial is terminated for safety. Moreover, the adverse events in this trial were not strictly related to dexmedetomidine dose, meaning that they are less predictable and that reducing the dose may not be a strategy for mitigation. This investigation exemplifies the critical need for carefully assessing the safety of multimodal regimens (and, in this case, opioid-free anesthesia), in addition to potential benefit, as has been called for previously in this Journal.10–12 and by others.13,14 Case in point, a 4-drug intraoperative non-opioid regime added no benefit to standard anesthesia and did not appreciably change postoperative opioid use or pain scores despite the greatly increased complexity of the anesthetics.12 The trial reported by Beloeil et al clearly demonstrates that we can do more harm than good by eliminating intraoperative opioids, depending on how we replace them.8

The narrative review9 is comprehensive, and concludes that while complete opioid sparing is possible in some contexts and procedures, there is no evidence that opioid-free strategies a) have benefits above and beyond opioid-sparing strategies, b) influence the risk or prevent persistent postoperative opioid use, or c) prevent postoperative opioid overprescription. In fact, there is little reason to suppose any of these hoped for benefits would accrue. The narrative remarks that opioid-free strategies, however noble in their cause, do not fully acknowledge the limitations and gaps in existing evidence and clinical practice considerations; do not allow analgesic titration based on patient needs; are unclear about optimal non-opioid components; have ill-defined roles in different surgical settings and perioperative phases; necessitate additional equipment, monitoring, resources, and cost; ignore concerns about safety and drug interactions; do not serve to decrease the risk of persistent opioid use; and, as a result, are unrealistic in routine clinical practice. Perhaps most importantly, the undue focus on opioid-free anesthesia may be distracting us from optimizing pain relief and minimizing long-term harms.

Looking back

What are the antecedents and potential drivers of “opioid-free anesthesia”? These may include inappropriate overreaction to the opioid crisis, opioid-sparing taken to an extreme, and misinterpretation of contemporary emphasis on enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) guidelines.

The opioid crisis

The current opioid crisis emanated from inappropriate prescribing, marketing, diversion, and misuse of oral prescription opioids for acute and chronic noncancer pain. The human and economic toll is staggering (400,000 US deaths over the past two decades, one quarter of which may be suicides, and $2.5 trillion costs for just 2015 to 2018, including $700B in 2018 alone – 3.4% of the US gross domestic product),15–18 and the problem is not limited to the US.19 Whether via the medical or lay press, no one is unaware of the opioid crisis, and opioid overdose has worsened with the COVID-19 pandemic.

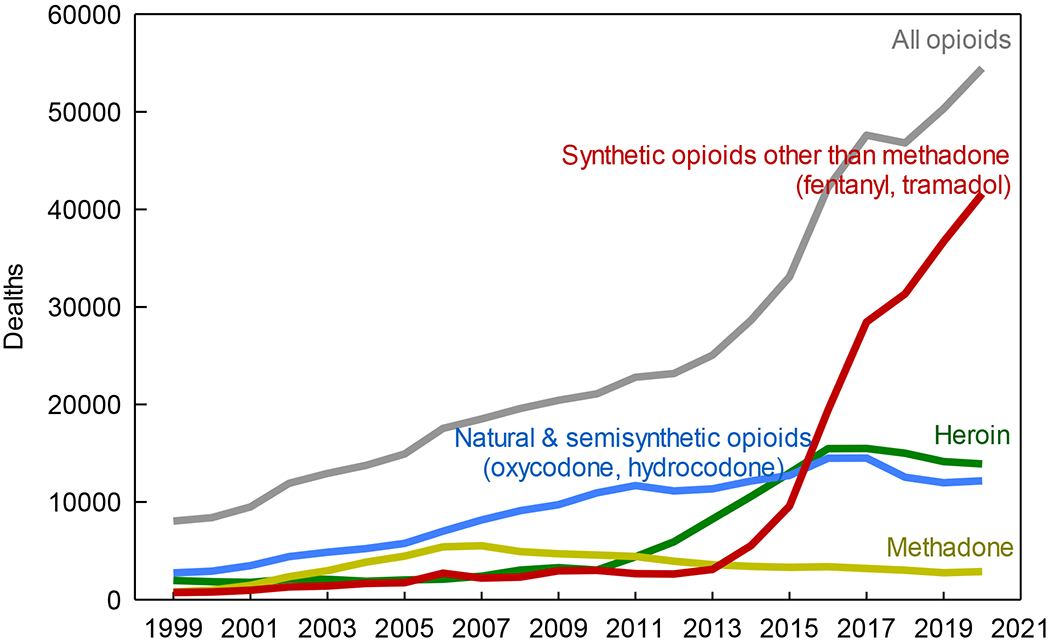

The opioid crisis has multiple antecedents, and the roots are even deeper than popular narratives and current medical literature portray. Opioids have been used medicinally for millennia. However more recent and successive waves of use have culminated in our current predicament. In the first wave (1960s) acute pain management with oral opioids was so common that propoxyphene was the second most commonly dispensed drug in the US.20 A second wave (1990s) saw further increases in oral opioid use for chronic pain treatment despite unclear evidence of effectiveness.20 A third wave (2001–2010) saw further expanded oral opioid use, with aggressive marketing, liberalized prescribing, and proliferating managed care, regulatory agency, and practice efficiency guidelines that encouraged expanded opioid prescribing. Indeed, from 2006–2010, hydrocodone-acetaminophen was the most widely prescribed drug in the US.21 Commensurate with increased oral opioid use during that time, the annual overdose deaths involving prescription oral opioids escalated by 182% (Figure 1).22,23 The fourth, most recent, and most devastating wave of opioid overdoses relates to escalating heroin and illicit fentanyl use (Figure 1), economic stress and employment deterioration,24 a shift of the abused opioid supply chain from medical to illicit sources, and a fluid substitution of illicit fentanyl for prescription opioids. Overall opioid prescribing has fortunately receded,25 yet overdose deaths have negligibly changed, due to this more lethal wave of heroin and illicit fentanyl abuse.26,27

Figure 1.

United States drug overdose deaths involving opioids 1999–2020 (November), by type of opioid. Data are accessed at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm

The point is this: Notably absent from this entire historical narrative is any mention of, association with, or causal attribution of the opioid crisis to intraoperative and immediate postoperative use of opioids to treat moderate-severe surgical pain. Similarly, it is a great and unfounded leap to say that there is an opioid crisis and therefore we must stop using opioids for surgery. Yet the steady drumbeat of the opioid crisis can influence practitioner behavior, voluntarily or subconsciously. If the concept and practice of “opioid free” anesthesia is a response to the opioid crisis, it is unnatural, unfounded, and perplexing.

Opioid-sparing vs opioid eradication

With the shift from balanced intraoperative anesthesia and postoperative analgesia with opioids as the only analgesic component to current concepts of balanced anesthesia and multimodal analgesia with opioids and other drugs, perhaps then just dropping opioids altogether was somehow seen as a logical or natural progression. After all, we have regional anesthesia, lidocaine, ketamine and other drugs that can contribute to the analgesic components of anesthetics. Opioids do have untoward side effects, the most bothersome being nausea and vomiting and the most dangerous being respiratory depression. Multimodal analgesic therapy is based on the theory of combining drugs to achieve additive benefit without additive risk or synergistic benefit with only additive risk. Multimodal approaches can clearly reduce pain and opioid consumption in some circumstances. All is not pure benefit, however, as many adjuvant drugs can actually increase the very side effects that are unwanted, or introduce new risks. For example, gabapentinoids, sedative-hypnotics, benzodiazepines, and “muscle relaxants” (e.g. baclofen and carisoprodol) can produce additive or event potentiate opioid-induced respiratory depression.28–30 This is not more benefit with less risk, but in fact more risk with less benefit.

Perhaps then the thinking was to change further, to ideally eliminate untoward opioid drug interactions by just eliminating opioids altogether. The problem is that opioids are the most efficacious analgesics available in many situations, and the remaining multimodal components alone are insufficiently effective against moderate-severe pain. No amount of wishing will turn acetaminophen into hydromorphone. While opioid-sparing (if it means avoiding excessive opioid use) is appropriate, opioid eradication, as identified by Shanthanna et al, is not, based on evidence to date. Opioid-sparing is not synonymous with opioid-absence.

Enhanced recovery after surgery and opioids

The objective of enhanced recovery after surgery protocols is to restore patients to their presurgical state of health as quickly as possible, as well as to reduce complications and standardize perioperative care to minimize variability and improve outcomes.13 Postoperative recovery is influenced primarily by minimally invasive (laparoscopic) surgical approaches and postoperative care (e.g. oral intake, early ambulation), and only one of the five key enhanced recovery protocol components originally associated with improved outcomes relates to anesthesia (epidurals in open colectomy).13,14 Nevertheless, enhanced recovery protocols have been increasingly laden by well-intentioned clinicians with more and more elements, simply added under the assumption they will provide additional benefit. Unfortunately these protocols and assumptions are often untested, unvalidated, and of unknown benefit and risk.14

Also problematic is that enhanced recovery protocols and consensus statements may overstate and/or misinterpret published literature to support assertions about opioids and the value of opioid eradication, and it is important to separate evidence from conventional wisdom and assumption. For example, a consensus review of optimal perioperative care in colorectal surgery from the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery Group claimed that adverse effects of opioids can hamper recovery and prolong length of stay, citing a Cochrane review, yet that review did not address opioids.31 A set of clinical practice guidelines for enhanced recovery after colon and rectal surgery from the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons and Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons claimed that multiple prospective studies (citing four) demonstrated that minimizing opioids was associated with earlier return of bowel function and shorter length of stay, yet inspection of those four studies found that none evaluated the specific contribution of postoperative opioids in isolation, and none eliminated opioid use entirely.32 Less may be better but it is not clear that none is best. Such overstatements notwithstanding, enhanced recovery protocols do not universally advocate for opioid eradication over rational use. Even the most recent enhanced recovery guidelines state that opioids cannot necessarily be avoided, and that analgesia is best provided by opioid-sparing, not by opioid eradication.33

Looking forward

It is time to regain our balance in anesthesia. Opioid-free anesthesia may be feasible. Nevertheless, it appears neither logical nor beneficial to patients. Feasibility is not a therapeutic indication nor is it patient-centric. In a hierarchical progression of values from feasible (can it be done?) to viable (does it have value?) to worthwhile (does it meet patient needs?) to desirable (do patients want it?) to optimal (does it best meet patient needs and optimize outcome?), feasibility is the lowest of value propositions.

Surgery hurts. Patients suffer from acute postoperative pain. More than 80% of patients report their postoperative pain is not adequately treated, a metric unchanged for decades.34–36 Depriving patients of analgesic opioids is unlikely to improve that metric. Additionally, poorly controlled acute postoperative pain is the greatest risk factor for chronic postoperative pain, which afflicts 10–60% of surgical patients.37,38 Moreover, acute postoperative pain is associated with complications - both generalized (postoperative cognitive decline, delirium, and sleep disturbances39) and surgical (surgical site and urinary tract infections,40 30d infection rates,41 and higher readmission rates42) So too is chronic postsurgical pain associated with postoperative complications.43 Patients who experience postoperative pain have poorer recovery, less satisfaction, and more regret about having had surgery.44 Non-opioid approaches to treating acute postoperative pain in order to prevent the transition to chronic postoperative pain, such as local and regional anesthesia, and non-opioid analgesics such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, NMDA-receptor antagonists and gabapentinoids have, unfortunately, not been successful.38 The history of excessive and inappropriate outpatient prescribing of oral opioids for chronic pain should not motivate the withholding of opioids for acute perioperative surgical pain. As stated previously, “perioperative practitioners should avoid making surgical patients pay with unnecessary suffering for the opioid overprescribing sins of others.”7

The clinical trial report8 and the comprehensive review9 in this issue of Anesthesiology demonstrate that it is time for the opioid pendulum to swing back from the unjustified extreme of opioid eradication to a more balanced and rational approach.7 While it is well-known that excessive opioid use can have adverse consequences that can and should be mitigated, swinging completely to the absence of opioids, in the name of whatever well-intentioned motivation, can also have adverse consequences that can and should be mitigated. There is a Goldilocks zone for opioids in which patients are provided the optimal balance of analgesia with minimal or no side effects or risks. The problem is that one dose regimen does not fit all. Personalized medicine is difficult to protocolize.

The challenge is to devise regimens, optimize drug selection, and deliver care which provides optimal intraoperative and immediate postoperative analgesia, and ideally also confers long-lasting benefit with improved recovery trajectories.45 For example, and the exact opposite of opioid eradication, the long-duration opioid methadone not only reduces intraoperative and immediate postoperative pain and opioid requirements, but also reduces pain and opioid consumption long after patients have left the health care institution.46–49 An “opioid-sparing opioid” like methadone might confer advantage over opioid eradication.

Optimal postoperative analgesia will only be achieved by using the available tools in a manner tailored to the specific needs of individual patients. Our preoccupation with opioid-free anesthesia and analgesia distracts us from this challenge. What is clear is that our current analgesic pharmacologic armamentarium is inadequate to the task of providing adequate pain relief with minimal side effects, and it has not materially changed in decades. While academia and industry regroup after years of failures, hopefully new molecular, cellular and systems-based approaches will help us to discover novel approaches to analgesia. In the meantime, we can work on using existing tools more effectively. We have not defined the optimal components of multimodal analgesic pathways nor have we developed tailored approaches consistent with the goals of precision medicine. Rather than toss aside opioids, some of our most powerful tools, we should focus on defining the optimal use of these important drugs.

Acknowledgments

Supported by National Institutes of Health grant No. R01 DA042985 (Bethesda, Maryland; to Dr. Kharasch) and Department of Veterans Affairs grant No. I01 BX000881 (Washington, D.C.; to Dr. Clark).

Footnotes

Dr. Kharasch has no competing interests Dr. Clark has a consulting agreement with Teikoku Pharma USA (San Jose, California).

References

- 1.Kharasch ED: Opioid half-lives and hemlines: The long and short of fashion. Anesthesiology 2015;122:969–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Society for Opioid Free Anesthesia.https://goopioidfree.com/, last accessed December 15, 2020

- 3.Lirk P, Rathmell JP: Opioid-free anaesthesia: Con: it is too early to adopt opioid-free anaesthesia today. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2019;36:250–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lavand’homme P: Opioid-free anaesthesia: Pro: damned if you don’t use opioids during surgery. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2019;36:247–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu CL, King AB, Geiger TM, Grant MC, Grocott MPW, Gupta R, Hah JM, Miller TE, Shaw AD, Gan TJ, Thacker JKM, Mythen MG, McEvoy MD: American Society for Enhanced Recovery and Perioperative Quality Initiative joint consensus statement on perioperative opioid minimization in opioid-naive patients. Anesth Analg 2019;129:567–577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Egan TD: Are opioids indispensable for general anaesthesia? Br J Anaesth 2019;122:e127–e135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kharasch ED, Avram MJ, Clark JD: Rational perioperative opioid management in the era of the opioid crisis. Anesthesiology 2020;132:603–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beloeil H, Garot M, Lebuffe G, Gerbaud A, Bila J, Cuvillon P, Dubout E, Oger S, Nadaud J, Becret A, Coullier N, Lecoeur S, Fayon J, Godet T, Mazerolles M, Atallah F, Sigaut S, Choinier P-M, Asehnoune K, Roquilly A, Chanques G, Esvan M, Futier E, Laviolle B: Balanced opioid-free anesthesia with dexmedetomidine vs balanced anesthesia with remifentanil for major or intermediate non-cardiac surgery: The POFA randomized clinical trial. Anesthesiology 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shanthanna H, Ladha KS, Kehlet H, Joshi GP: Perioperative opioid administration: A critical review of opioid-free versus opioid-sparing approaches. Anesthesiology 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kharasch ED, Eisenach JC: Wherefore gabapentinoids? Was there rush too soon to judgement? Anesthesiology 2016;124:10–2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kharasch ED, Clark JD, Kheterpal S: Perioperative gabapentinoids: Deflating the bubble. Anesthesiology 2020;133:251–254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maheshwari K, Avitsian R, Sessler DI, Makarova N, Tanios M, Raza S, Traul D, Rajan S, Manlapaz M, Machado S, Krishnaney A, Machado A, Rosenquist R, Kurz A: Multimodal analgesic regimen for spine surgery: A randomized placebo-controlled trial. Anesthesiology 2020;132:992–1002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joshi GP, Kehlet H: Enhanced recovery pathways: Looking Into the future. Anesth Analg 2019;128:5–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Memtsoudis SG, Poeran J, Kehlet H: Enhanced recovery after surgery in the United States: From evidence-based practice to uncertain science? JAMA 2019;321:1049–1050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oquendo MA, Volkow ND: Suicide: A silent contributor to opioid-overdose deaths. N Engl J Med 2018;378:1567–1569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The Council on Economic Advisers: The full cost of the opioid crisis: $2.5 trillion over four years https://www.whitehouse.gov/articles/full-cost-opioid-crisis-2-5-trillion-four-years/, 2019, last accessed December 15, 2020

- 17.Hubbard WK: Getting serious about opioid regulation. JAMA Intern Med 2020;180:309–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.The Economist: The wider effects of America’s opioid epidemic https://www.economist.com/business/2020/01/16/the-wider-effects-of-americas-opioid-epidemic 2020, last accessed December 15, 2020

- 19.Verhamme KMC, Bohnen AM: Are we facing an opioid crisis in Europe? Lancet Public Health 2019;4:e483–e484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dasgupta N, Beletsky L, Ciccarone D: Opioid crisis: No easy fix to its social and economic determinants. Am J Public Health 2018;108:182–186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stoddard KI, Huggett DB: Wastewater effluent hydrocodone concentrations as an indicator of drug disposal program success. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol 2015;95:139–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.The Council of Economic Advisors: The role of opioid prices in the evolving opioid crisis. Washington, D.C., The White House, 2019, last accessed December 15, 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hedegaard H, Miniño AM, Warner M: Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999–2018. Hyattsville, MD, National Center for Health Statistics, 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seltzer N: The economic underpinnings of the drug epidemic. SSM Popul Health 2020;12:100679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhu W, Chernew ME, Sherry TB, Maestas N: Initial opioid prescriptions among U.S. commercially insured patients, 2012–2017. N Engl J Med 2019;380:1043–1052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alpert A, Powell D, Pacula RL: Supply-side drug policy in the presence of substitutes: Evidence from the introduction of abuse-deterrent opioids. Am Econ J Econ Policy 2018;10:1–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilson N, Kariisa M, Seth P, Smith Ht, Davis NL: Drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths - United States, 2017–2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:290–297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Verret M, Lauzier F, Zarychanski R, Perron C, Savard X, Pinard A-M, Leblanc G, Cossi M-J, Neveu X, Turgeon AF: Perioperative use of gabapentinoids for the management of postoperative acute pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Anesthesiology 2020;133:265–27932667154 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Izrailtyan I, Qiu J, Overdyk FJ, Erslon M, Gan TJ: Risk factors for cardiopulmonary and respiratory arrest in medical and surgical hospital patients on opioid analgesics and sedatives. PLoS One 2018;13:e0194553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li Y, Delcher C, Wei YJ, Reisfield GM, Brown JD, Tighe P, Winterstein AG: Risk of opioid overdose associated with concomitant use of opioids and skeletal muscle relaxants: A population-based cohort study. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2020;108:81–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lassen K, Soop M, Nygren J, Cox PB, Hendry PO, Spies C, von Meyenfeldt MF, Fearon KC, Revhaug A, Norderval S, Ljungqvist O, Lobo DN, Dejong CH: Consensus review of optimal perioperative care in colorectal surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Group recommendations. Arch Surg 2009;144:961–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carmichael JC, Keller DS, Baldini G, Bordeianou L, Weiss E, Lee L, Boutros M, McClane J, Feldman LS, Steele SR: Clinical practice guidelines for enhanced recovery after colon and rectal surgery from the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons and Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons. Dis Colon Rectum 2017;60:761–784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gustafsson UO, Scott MJ, Hubner M, Nygren J, Demartines N, Francis N, Rockall TA, Young-Fadok TM, Hill AG, Soop M, de Boer HD, Urman RD, Chang GJ, Fichera A, Kessler H, Grass F, Whang EE, Fawcett WJ, Carli F, Lobo DN, Rollins KE, Balfour A, Baldini G, Riedel B, Ljungqvist O: Guidelines for perioperative care in elective colorectal surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Society recommendations: 2018. World J Surg 2019;43:659–695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu CL, Berenholtz SM, Pronovost PJ, Fleisher LA: Systematic review and analysis of postdischarge symptoms after outpatient surgery. Anesthesiology 2002;96:994–1003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gan TJ: Poorly controlled postoperative pain: prevalence, consequences, and prevention. J Pain Res 2017;10:2287–2298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meissner W, Zaslansky R: A survey of postoperative pain treatments and unmet needs. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 2019;33:269–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Perkins FM, Kehlet H: Chronic pain as an outcome of surgery. A review of predictive factors. Anesthesiology 2000;93:1123–1133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Glare P, Aubrey KR, Myles PS: Transition from acute to chronic pain after surgery. Lancet 2019;393:1537–1546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu CL, Rowlingson AJ, Partin AW, Kalish MA, Courpas GE, Walsh PC, Fleisher LA: Correlation of postoperative pain to quality of recovery in the immediate postoperative period. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2005;30:516–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Boekel RLM, Warle MC, Nielen RGC, Vissers KCP, van der Sande R, Bronkhorst EM, Lerou JGC, Steegers MAH: Relationship between postoperative pain and overall 30-day complications in a broad surgical population: An observational study. Ann Surg 2019;269:856–865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Albers KI, van Helden EV, Dahan A, Martini CH, Bruintjes MHD, Scheffer GJ, Steegers MAH, Keijzer C, Warle MC: Early postoperative pain after laparoscopic donor nephrectomy predicts 30-day postoperative infectious complications: a pooled analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pain 2020;161:1565–1570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hernandez-Boussard T, Graham LA, Desai K, Wahl TS, Aucoin E, Richman JS, Morris MS, Itani KM, Telford GL, Hawn MT: The fifth vital sign: postoperative pain predicts 30-day readmissions and subsequent emergency department visits. Ann Surg 2017;266:516–524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Willingham M, Rangrass G, Curcuru C, Ben Abdallah A, Wildes TS, McKinnon S, Kronzer A, Sharma A, Helsten D, Hall B, Avidan MS, Haroutounian S: Association between postoperative complications and lingering post-surgical pain: An observational cohort study. Br J Anaesth 2020;124:214–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Berkowitz R, Vu J, Brummett C, Waljee J, Englesbe M, Howard R: The impact of complications and pain on patient satisfaction. Ann Surg 2020:in press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kharasch ED, Brunt LM: Perioperative opioids and public health. Anesthesiology 2016;124:960–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kharasch ED: Intraoperative methadone: rediscovery, reappraisal, and reinvigoration? Anesth Analg 2011;112:13–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Murphy GS, Szokol JW: Intraoperative methadone in surgical patients: A review of clinical investigations. Anesthesiology 2019;131:678–692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Komen H, Brunt LM, Deych E, Blood J, Kharasch ED: Intraoperative methadone in same-day ambulatory surgery: A randomized, double-blinded, dose-finding pilot study. Anesth Analg 2019;128:802–810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Murphy GS, Avram MJ, Greenberg SB, Shear TD, Deshur MA, Dickerson D, Bilimoria S, Benson J, Maher CE, Trenk GJ, Teister KJ, Szokol JW: Postoperative pain and analgesic requirements in the first year after intraoperative methadone for complex spine and cardiac surgery. Anesthesiology 2020;132:330–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]