Abstract

Objective

We present the protocol of a study aiming to examine the efficacy of a technologically-mediated storytelling intervention called Caregiver Speaks in reducing distress and grief intensity experienced by active and bereaved hospice family caregivers of persons living with dementia (PLWD).

Design

The study is a mixed-method, two-group, randomized controlled trial.

Setting

This study takes place in five hospice agencies in the Midwest and Northeastern United States.

Participants

Participants include hospice family caregivers of PLWD.

Intervention

Participants are randomized to usual hospice care or the intervention group. In the Caregiver Speaks intervention, caregivers engage in photo-elicitation storytelling (sharing photos that capture their thoughts, feelings, and reactions to caregiving and bereavement) via a privately facilitated Facebook group. This intervention will longitudinally follow caregivers from active caregiving into bereavement. The usual care group continues to receive hospice care but does not participate in the online group.

Outcomes Measured

We anticipate enrolling 468 participants. Our primary outcomes of interest are participant depression and anxiety, which are measured by the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder screening (GAD-7). Our secondary outcomes of interest are participants’ perceived social support, measured by the Perceived Social Support for Caregiving (PSSC) scale, and grief intensity, which is measured by the Texas Revised Inventory of Grief Present Subscale (TRIG-Present).

Keywords: caregiver distress, grief, dementia, hospice, bereavement

Introduction

Over 15 million Americans living with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias receive daily care from family caregivers—unpaid individuals who are typically related to the care recipient and assume responsibility for daily care and decision-making.1 Caring for a person living with dementia (PLWD) greatly alters caregivers’ daily lives, often resulting in depression and anxiety as they labor throughout the illness trajectory.2–4 Caregiving challenges typically increase as the patient nears death,5–8 yet family caregivers of PLWD often lack support during this terminal phase and bereavement. Lack of support at this difficult time intensifies both caregiving-related distress and caregivers’ grief.9–11

Caregivers’ pre-bereavement experience are associated with how well they adapt to their post-loss lives.7,12 Caregivers who experience pre-bereavement depression, anxiety, and inadequate social support are likely to experience more intense grief and distress after their care recipient dies.11,13–15 Thus, interventions that reduce caregivers’ pre-bereavement depression and anxiety may improve the caregiving experience and bereavement journey.6–8,16 Hospice is one of the few healthcare services that follows caregivers into bereavement. Although Medicare Conditions of Participation require hospice agencies to deliver bereavement services, no standards exist to prescribe what these services should include or how they should be delivered.17 Furthermore, many hospice agencies lack resources to provide comprehensive services to all bereaved caregivers.17 Thus it is not surprising that current efforts for supporting hospice caregivers of PLWD show little efficacy at reducing pre- and post-loss depression and anxiety during caregiving or into bereavement.7,12

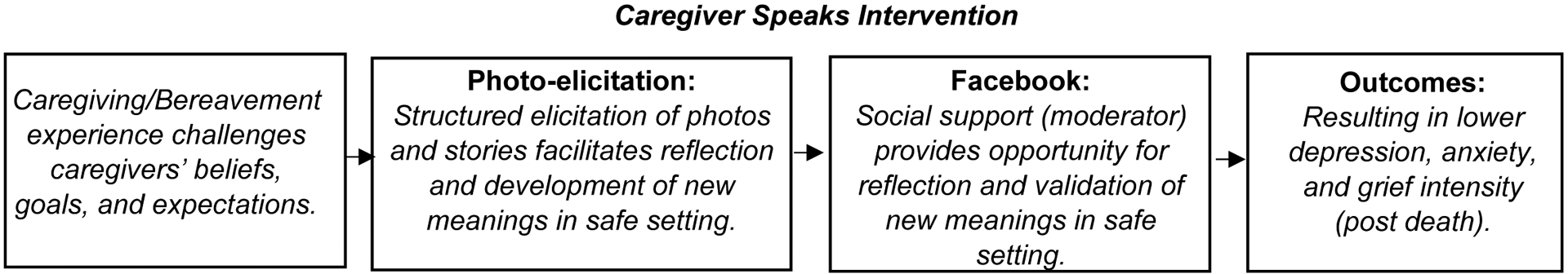

The authors are conducting a two-arm, multi-site, randomized controlled trial of a technologically-mediated storytelling intervention called Caregiver Speaks. Caregiver Speaks empowers caregivers’ self-expression, moderated by increased social support, to make meaning of the caregiving and bereavement experiences, thus reducing depression and anxiety. The scientific premise of this intervention is informed by Park and Folkman’s meaning-making coping model18 (see Figure 1), which posits that an individual’s ability to make sense of, and find benefit in, an adverse life situation (e.g., caregiving and bereavement) will be enhanced by social support, resulting in reduced depression, anxiety, and grief intensity.13,19–21 Described more in depth below, Caregiver Speaks employs photo-elicitation—the use of photos to elicit caregivers’ thoughts and feelings about their experiences—and a private Facebook (FB) group to enable them to capture and share their stories in a supportive online environment.

Figure 1.

Adapted Meaning-Making Model of Stress and Coping

In this article we describe the protocol for a study that tests the efficacy of the Caregiver Speaks intervention. To our knowledge, this is the first hospice intervention offered during active caregiving that follows caregivers into bereavement using the innovative storytelling technique of photo-elicitation. We aim to: 1) Determine the efficacy of the Caregiver Speaks intervention in reducing depression and anxiety among hospice family caregivers of PLWD, 2) Examine the effect of the Caregiver Speaks intervention on grief intensity among bereaved hospice family caregivers of PLWD, and 3) Describe how caregivers make meaning of their caregiving and bereavement experiences. Qualitative and quantitative data will be collected throughout and given the same weight in the final analysis. We hypothesize that hospice family caregivers of PLWD who participate in Caregiver Speaks will experience more social support (mediating variable) and thus less depression and anxiety during caregiving (outcome), and less intense grief (outcome) during bereavement than those receiving usual hospice care. All associated research questions and hypotheses are located in Table 2.

Table 2: Aims, Hypotheses, and Associated Measures.

Pre-bereavement measures collected at baseline, 14, 30, 90, and 150 days. Post-death measures collected at transition, 14, 30, 90, 150 and 180 days.

| Specific Aim | Hypotheses (H) and Research Questions (RQ) | Instruments and Variables | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aim 1: Determine the efficacy of the Caregiver Speaks intervention in reducing depression and anxiety among hospice family caregivers of PLWD. |

RQ1: What is the effect of the Caregiver Speaks intervention on caregivers’ depression, anxiety (outcomes of interest)? H1a: Family caregivers receiving the intervention will report lower depression and anxiety (outcomes of interest), which is facilitated by higher social support (mediating variable) than those in the control group during active caregiving. H1b: Family caregivers receiving the intervention will report lower depression and anxiety (outcomes of interest), which is facilitated by higher social support (mediating variable) than those in the control group during bereavement. H1c: the intervention group, family caregivers with higher baseline depression scores will experience a larger reduction in depression compared to those with less depression at baseline. |

Primary Outcome:

Depression Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) Secondary Outcome: Anxiety Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) Mediating Variables: Social Validation & Growth: Social Meaning in Life Events Scale –Social Validation SMILES-SV Integration of Stressful Life Experiences Scale Short Form (ISLES-SF) Caregiver Quality of Life Index (CQLI-R) |

PHQ-9: a 9-item screening tool to capture presence of depressive symptoms.37 Internal Consistency: .8738 GAD-7: a 7-item screening tool and severity measure for generalized anxiety. Internal Consistency: .8939 SMILES-SV: a 9-item tool for measuring social validation and meaning-making during stressful life events. Internal Reliability: .8440 ISLES-SF: a 6-item measure that assess meanings made of stress during bereavement.41 CQLI-R: a 4-item scale that measures physical, social, emotional, and financial quality of life among active caregivers. |

| Aim 2: Examine the effect of the Caregiver Speaks intervention on grief intensity among bereaved hospice family caregivers of PLWD | H2: Bereaved family caregivers receiving the intervention will report lower grief intensity (outcome of interest) than those in the control group. | Secondary Outcome: Grief Intensity Texas Revised Inventory of Grief (TRIG)-Present Scale | TRIG-Present: a 13-item scale measuring present grief among bereaved individuals. Internal Consistency: .8642,43 |

| Aim 3: Describe how caregivers make meaning of their caregiving and bereavement experiences | RQ2: In what ways do active caregivers find meaning as reflected in their FB posts? RQ3: In what ways do bereaved caregivers find meaning as reflected in their FB posts? RQ4: In what ways does the social support in an online group facilitate meaning making? |

SMILES-SV and TRIG-Present | Triangulation of qualitative analysis of photos, discussion of photos via Facebook Group, and interview transcripts with SMILES-SV and TRIG. |

Methods

Study Design and Sampling Strategy

We are conducting a two-group, randomized trial with anticipated enrollment of 468 participants (234 per group). Based on the literature and our preliminary work regarding the prevalence of depression and its impact on bereavement, we selected depression as our primary outcome. We are powering this intervention on the PHQ-9 (depression inventory), a commonly used tool for bereaved individuals. The PHQ-9 is a reliable, valid, and sensitive tool for this population.22–25 Our power calculations based on our preliminary work hold the following assumptions: 1) attrition rate of 30%, 2) 80% power, 3) a two-sided alternative for group differences at the 0.05 level of significance, and 4) a change in PHQ-9 score with a mean of 4 points and a variance of 5.5.

Participants and Setting

Participants are hospice family caregivers of PLWD. In the United States, hospice serves most individuals in their residence, nursing homes, or other long-term care environments. Therefore our sample includes these locations. Participants are recruited from five hospice agencies in the Midwest and Northeastern United States. These hospice agencies serve a diverse population, including rural, urban and suburban areas.

The study’s target population is the designated family caregivers of hospice patients of persons living with dementia (PLWD). Our extensive hospice research experience has found that the majority of hospice family caregivers are female spouses or daughters. Thus, no special recruitment procedures for women will be necessary because they are adequately represented in this population. However, we will ensure that more than half of the participants will be women.

We also recognize the many well-documented challenges of recruiting minority participants in hospice and palliative care studies. These challenges require planning and monitoring to assure that minorities are adequately represented in such research. Therefore, the protocol itself was designed welcoming environment that is sensitive of the concerns for minority populations and appreciative of what participants contribute to research. Furthermore, all research staff have been trained in cultural sensitivity, and when possible, minority investigators and staff have been and will be solicited to participate.

Eligibility Criteria

Eligible participants must 1) be a designated family caregiver (i.e., a family member or friend providing unpaid care) of a PLWD who is enrolled in hospice care, 2) be at least 18 years old, 3) be involved in decisions related to their loved one’s hospice care, 4) have access to a digital camera or other photo-taking device such as a cell phone, 5) be willing to photograph images they feel capture their caregiving and bereavement experiences, 6) be willing to set up a Facebook account and join the private Facebook group, and 7) have access to e-mail for survey data collection. Family caregivers without an internet-enabled device are given a smart phone and data plan restricted to Facebook use for the duration of their participation in the study.

Recruitment, Randomization, and Consent

Upon a patient’s enrollment in hospice, a hospice staff member gives eligible caregivers a brochure explaining the study. When family caregivers express interest, the staff member requests their verbal permission for a member of our research team to contact them via phone. We have successfully used this recruitment strategy in a prior study.26 Consented participants are randomized into two equal groups (Caregiver Speaks intervention or usual hospice care) using the randomization module in the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) system. Once assigned to an arm, the participant remains in that arm for the entire study, from active caregiving through bereavement. It is important to note that while the participants will be randomized into two equal groups, the intervention group will not have 234 participants in it at one time. Participants will phase into the Facebook groups at varying times depending on date of enrollment and date of patient death. Our previous pilot of this intervention,27 as well as other preliminary work running online social support groups for hospice family caregivers and patients with chronic pain,28,29 suggest that anywhere between 10 and 30 participants in a group at one time lends itself to meaningful interaction amongst group members.

Intervention Protocol

Participants assigned to the control group receive usual care - standard hospice care and bereavement support from their hospice agency and are asked to complete study measures electronically at the same intervals as the participants in the intervention group. We considered using an attention control but chose usual care instead, as prior research demonstrated that using an attention control in a behavioral randomized trial is problematic,30 especially for outcomes such as depression (our primary outcome of interest) and anxiety. This literature advocates that controlling for attention is not necessary and counterproductive in some behavioral intervention trials.30

Participants assigned to the intervention group receive usual care plus the Caregiver Speaks intervention. As part of participation, they join a Facebook group in which they share photos and personal stories of what it means to be an active caregiver of a PLWD, and after the patient’s death, bereaved. Caregivers assigned to the Caregiver Speaks intervention receive assistance in setting up a Facebook account (if needed) and information regarding privacy concerns for photo taking during a one-time orientation call. At this time, the interventionist also discusses elements of their caregiving story, identifies artifacts they may wish to feature in their photo-elicitation process, and enrolls them in the active caregiver private Facebook group. Caregivers participate in this group until the PLWD dies, at which time they transition (one month later) into a bereavement-focused group. The bereavement group includes the same components, but the focus of the photos and conversation are on bereavement. Table 1 provides a summary of the study and intervention participation. We provide caregivers a reference guide for using Facebook, including group rules and common Facebook terms, based on materials we have used extensively in our preliminary work.31

Table 1.

Summary of Study/Intervention Participation for Caregiver Speaks

| Time | Study/Intervention Procedures |

|---|---|

| Recruitment | Flyer given to interested participants by hospice admissions staff, consent given for research staff to contact participant, phone meeting (orientation) scheduled. |

| Phone (orientation) meeting and randomization | Informed consent obtained; randomization to group; instructions given to intervention group for Facebook and photo-elicitation procedures. |

| Weekly (pre-bereaved caregiver Facebook group) | Research staff will facilitate ongoing discussion of photos and caregiver experiences. Research staff will encourage participants to post weekly. |

| 1-month bereavement transition | Once bereaved, caregivers will have one month to transition into the bereavement group. Research staff will 1) walk them through the steps of joining the bereavement group, 2) give instructions, and 3) conduct a brief, semi-structured, qualitative interview. |

| Weekly (bereaved caregiver Facebook group) | Research staff will facilitate discussion of photos. This will continue up to ~180 days (6 months) after the death of their loved one. Research staff will encourage participants to post weekly. |

| Study exit | Termination and follow-up: participants will terminate from the group, and will complete 180-day survey and follow-up interview. |

Photos are the primary medium through which participants engage with other group members. Before their loved one dies, caregivers are asked to take photographs that they feel best capture their daily caregiving and share them with other caregivers in the active caregiving Facebook group. The primary group moderator asks caregivers to focus their photo-taking and discussion on their meaning structures as caregivers (including their pre-caregiving lives) and how they have changed over the course of the illness. For example, caregivers may capture their daily activities caring for their family member, their perceptions of themselves and their interpersonal relationships (including how these changed when they assumed the caregiver role), and how caregiving affects their views of the future and their world. Caregivers who enter the bereavement phase of the study are asked to take photographs capturing their post-loss meaning structures (e.g., how their sense of self has changed in bereavement, re-examined priorities for life, relationships with the living and continued bonds with the dead, and how their views of the world and future have changed). Members will be asked to discuss these things with others in the bereavement group.

Safety and Ethical Considerations and Institutional Review Board Approval

This study was approved by the primary author’s institutional review board. Hospice family caregivers incur minimal risk by participating in the study. Potential risks include sadness and renewed grief reactions, frustration or anxiety with malfunctioning or technically deficient equipment. Some individuals entering the study might not know how to use Facebook, which may cause some anxiety or frustration. Participants may feel nervous about sharing photos on Facebook and engaging with other hospice family caregivers via the private group. They may also feel uncomfortable discussing their active caregiving and bereavement experiences on this platform.

The Facebook platform presents special considerations of risk and privacy. The consent form makes these issues known, and the protocol requires research staff to review participants’ privacy settings. We recommend the strictest settings. We tell potential participants that if they join the study, their name will be added to a “closed secret” Facebook page, giving them access to other hospice family caregivers of persons living with dementia (PLWD) enrolled in the study. Closed secret Facebooks groups are not searchable, and participants must receive an invitation to join. Although the research team controls membership in this group, participants are advised to protect their personal information and privacy with their individual privacy settings. Members of the Facebook group may contact one another through the Facebook website. However, the research team does not share participants’ personal contact information.

To participate in the intervention, participants must join Facebook and have an account. They are advised to read the Facebook privacy policy and set their Facebook privacy settings with the tightest controls. Over the phone, our research staff review the privacy settings with participants to assist them in understanding their meaning. However, participants decide on their own Facebook privacy settings. They are told that the settings of other group members might affect the privacy of what they share. We also inform participants of Facebook’s policy that it owns all materials placed on the Facebook website, and advise them to read the policy when posting photos. If participants wish to feature non-consented individuals in their photos, they are asked to obtain verbal consent from these individuals before posting the photo in the group. As members of the secret Facebook group, we encourage participants to discuss experiences, share caregiving advice, and access questions and concerns regarding similar issues with others enrolled in the intervention via the Facebook group.

Data Collection and Analysis Plan

Table 2 describes the data collection time points, outcomes, and measures used in this study.

We use the secure REDCap network to store all study data and data collection instruments, schedule follow-up assessments, monitor enrollment, and manage secure storage. The lead data manager provides technical support for the data-capture system. At pre-specified intervals, participants are sent a link by e-mail with instructions on how to complete the surveys. All photos, qualitative Facebook data, and transcribed interviews are entered into qualitative coding software (Dedoose) for triangulation (use of multiple data sources to ensure a rich and robust dataset)32,33 and thematic analysis.34

Based on entered data, the data manager produces reports of apparent data discrepancies and missing data. Any data concerns are addressed through the data/statistical team and reported to the research Steering committee, which is comprised of investigators from the research team, including the principal investigators. The role of the steering committee is to discuss any project related issues or concerns, including recruitment and onboarding challenges, intervention issues, and staff concerns. Larger concerns with the protocols are forwarded to the full team or institutional committees depending on their severity. Intervention fidelity and data quality is monitored by random inspection of the completed surveys by the member of the Intervention Committee and the lead data manager. Any problems detected are discussed with the Steering Committee.

In compliance with the reporting requirements, a Data and Safety Monitoring Plan (DSMP) is part of this trial. The DSMP report includes participants’ socio-demographic characteristics, expected-versus-actual recruitment rates, retention rates, any quality assurance or regulatory issues that occurred during the past year, summary of adverse events and serious adverse events, and any actions or changes regarding the protocol.

Conclusions

This randomized trial tests the Caregiver Speaks intervention among a vulnerable population – hospice family caregivers of persons living with dementia (PLWD). This study addresses the urgent need for evidence-based interventions that improve caregivers’ experiences4,35,36 from enrollment in hospice through bereavement.6–8 The intervention is innovative because: 1) it spans the final period of the PLWD’s life as well as the caregiver’s bereavement period, 2) photo-elicitation is an innovative storytelling approach that has not been extensively used in this population to provide social support, and 3) Caregiver Speaks uses a low-cost, readily-available technology (Facebook) to deliver the storytelling intervention as well as to increase social support, which enhances meaning-making in caregiving and bereavement.

The research is conducted by a highly collaborative and multidisciplinary research team that represents the fields of medicine, nursing, social work, family science, informatics, health services research, and public health. This research team exemplifies expertise in photo-elicitation and narrative storywork as well as palliative and end-of-life care.

Potential Challenges and Limitations

There are limitations to this study. First, the timing of death will differ for each participant, which could impact the pre-bereavement dose of the intervention (i.e., active caregiving phase) as the length of time spent in the pre-bereaved caregiver Facebook group will likely differ for each participant. Secondly, although the possibility is uncertain, potential exists for contamination because we are randomizing at the individual level, and not at the hospice level. If more than one family member is assigned to a hospice patient and consent to participate they are all randomized to the same group, thus reducing risk of contamination. Because hospice staff are not facilitating the intervention, contamination should not be a major issue in this study. Also, to receive the intervention in Facebook, the Facebook moderator or another member of the research team must invite the participant to join.

Timeline

The project timeline can be found in Table 3, below.

Table 3:

Project Timeline

| Months | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activity | 1–6 | 7–12 | 13–24 | 25–36 | 37–42 | 43–48 | 49–54 | 55–60 |

| Obtain IRB approval | X | |||||||

| Create Secret Facebook Group pages and Training Materials for Joining Facebook | X | |||||||

| Finalize REDCap Surveys and Processes | X | |||||||

| Hire and Train Research Staff | X | |||||||

| Enroll hospice family caregivers | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Data collection | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Preliminary analyses | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Develop Implementation Manual | X | |||||||

| Complete analyses | X | |||||||

| Disseminate findings | X | X | X | X | X | |||

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01AG059818. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Alzheimer’s Association. 2015 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11(3):332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Differences between caregivers and noncaregivers in psychological health and physical health: a meta-analysis. Psychol Aging. 2003;18(2):250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Associations of caregiver stressors and uplifts with subjective well-being and depressive mood: a meta-analytic comparison. Aging Ment Health. 2004;8(5):438–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sörensen S, Pinquart M, Duberstein P. How effective are interventions with caregivers? An updated meta-analysis. Gerontologist. 2002;42(3):356–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haley WE, Bergman EJ, Roth DL, McVie T, Gaugler JE, Mittelman MS. Long-term effects of bereavement and caregiver intervention on dementia caregiver depressive symptoms. Gerontologist. 2008;48(6):732–740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schulz R, Boerner K, Shear K, Zhang S, Gitlin LN. Predictors of complicated grief among dementia caregivers: a prospective study of bereavement. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(8):650–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schulz R, Hebert R, Boerner K. Bereavement after caregiving. Geriatrics. 2008;63(1):20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schulz R, Mendelsohn AB, Haley WE, et al. End-of-life care and the effects of bereavement on family caregivers of persons with dementia. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(20):1936–1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Godwin B, Waters H. ‘In solitary confinement’: Planning end-of-life well-being with people with advanced dementia, their family and professional carers. Mortality. 2009;14(3):265–285. [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCarty CE, Volicer L. Hospice access for individuals with dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2009;24(6):476–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanders S, Ott CH, Kelber ST, Noonan P. The experience of high levels of grief in caregivers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementia. Death Stud. 2008;32(6):495–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stroebe M, Schut H, Stroebe W. Attachment in Coping With Bereavement: A Theoretical Integration. Rev Gen Psychol. 2005;9(1):48. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boerner K, Schulz R, Horowitz A. Positive aspects of caregiving and adaptation to bereavement. Psychol Aging. 2004;19(4):668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hebert RS, Dang Q, Schulz R. Preparedness for the death of a loved one and mental health in bereaved caregivers of patients with dementia: findings from the REACH study. J Palliat Med. 2006;9(3):683–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lobb EA, Kristjanson LJ, Aoun SM, Monterosso L, Halkett GK, Davies A. Predictors of complicated grief: A systematic review of empirical studies. Death Stud. 2010;34(8):673–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang B, El-Jawahri A, Prigerson HG. Update on bereavement research: Evidence-based guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of complicated bereavement. J Palliat Med. 2006;9(5):1188–1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Demmer C. A national survey of hospice bereavement services. Omega-J Death Dying. 2003;47(4):327–341. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park CL, Folkman S. Meaning in the context of stress and coping. Rev Gen Psychol. 1997;1(2):115. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park CL. Religion as a Meaning-Making Framework in Coping with Life Stress. J Soc Issues. 2005;61(4):707–729. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gillies J, Neimeyer RA. Loss, grief, and the search for significance: Toward a model of meaning reconstruction in bereavement. J Constr Psychol. 2006;19(1):31–65. [Google Scholar]

- 21.MacKinnon CJ, Milman E, Smith NG, et al. Means to Meaning in Cancer-Related Bereavement. Couns Psychol. 2012;41(2):216–239. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huh HJ, Huh S, Lee SH, Chae JH. Unresolved Bereavement and Other Mental Health Problems in Parents of the Sewol Ferry Accident after 18 Months. Psychiatry investigation. 2017;14(3):231–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamaguchi T, Maeda I, Hatano Y, et al. Effects of End-of-Life Discussions on the Mental Health of Bereaved Family Members and Quality of Patient Death and Care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;54(1):17–26.e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller MD, Stack J, Reynolds CF 3rd. A Two-Tiered Strategy for Preventing Complications of Bereavement in the First Thirteen Months Post-Loss: A Pilot Study Using Peer Supports with Professional Therapist Back-up. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;26(3):350–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aoyama M, Sakaguchi Y, Morita T, et al. Factors associated with possible complicated grief and major depressive disorders. Psychooncology. 2018;27(3):915–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kruse RL, Parker Oliver D, Wittenberg-Lyles E, Demiris G. Conducting the ACTIVE randomized trial in hospice care: keys to success. Clinical Trials. 2013;10(1):160–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parker Oliver D, Rolbiecki A, Washington K, et al. Families Involved in Nursing Home Decision-making (FIND): A Mixed Methods Pilot Pragmatic Randomized Controlled Trial for Nursing Home Residents with Serious Illness. . The Gerontologist. (2018);(Under Review). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oliver DP, Washington K, Wittenberg-Lyles E, Gage A, Mooney M, Demiris G. Lessons learned from a secret Facebook support group. Health Soc Work. 2015;40(2):125–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rolbiecki A, Crenshaw B, Teti M, Ordway J, LeMaster JW, Mehr DR. Exploring Lived Experiences of Chronic Pain Through Photo-Elicitation and Social Networking. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Freedland KE. Demanding attention: reconsidering the role of attention control groups in behavioral intervention research. Psychosom Med. 2013;75(2):100–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parker Oliver D, Washington K, Gage LA, Demiris G. The promise of secret Facebook groups for active family caregivers of hospice patients. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(11):1199–1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carter N, Bryant-Lukosius D, DiCenso A, Blythe J, Neville AJ. The use of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2014;41(5):545–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patton MQ. Enhancing the quality and credibility of qualitative analysis. Health Serv Res. 1999;34(5 Pt 2):1189. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Braun V, Clarke V, Terry G. Thematic analysis. Qual Res Clin Health Psychol. 2014;24:95–114. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aziz NM, Miller JL, Curtis JR. Palliative and End of Life Care Research: Embracing New Opportunities. Nurs Outlook. 2012;60(6):384–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arruda EH, Paun O. Dementia caregiver grief and bereavement: an integrative review. West J Nurs Res. 2017;39(6):825–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kroencke K, Spitzer R, Williams J. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure [Electronic version]. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kocalevent R-D, Hinz A, Brähler E. Standardization of the depression screener patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9) in the general population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013;35(5):551–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Löwe B, Decker O, Müller S, et al. Validation and standardization of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med Care. 2008;46(3):266–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bellet BW, Holland JM, Neimeyer RA. The Social Meaning in Life Events Scale (SMILES): A preliminary psychometric evaluation in a bereaved sample. Death Stud. 2019;43(2):103–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Holland JM, Currier JM, Neimeyer RA. Validation of the integration of stressful life experiences scale–short form in a bereaved sample. Death Stud. 2014;38(4):234–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Crespo M, Piccini AT, Bernaldo-de-Quiros M. When the Care Ends: Emotional State of Spanish Bereaved Caregivers of Persons with Dementia. Span J Psychol. 2013;16. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Faschingbauer TR, Devaul RA, Zisook S. Development of the Texas Inventory of Grief. Am J Psychiatry. 1977;134(6):696–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]