Summary

We present a proteogenomic study of 108 human papilloma virus (HPV)-negative head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCCs). Proteomic analysis systematically catalogs HNSCC-associated proteins and phosphosites, prioritizes copy number drivers and highlights an oncogenic role for RNA processing genes. Proteomic investigation of mutual exclusivity between FAT1 truncating mutations and 11q13.3 amplifications reveals dysregulated actin dynamics as a common functional consequence. Phosphoproteomics characterizes two modes of EGFR activation, suggesting a new strategy to stratify HNSCCs based on EGFR ligand abundance for effective treatment with inhibitory EGFR monoclonal antibodies. Widespread deletion of immune modulatory genes accounts for low immune infiltration in immune-cold tumors, whereas concordant upregulation of multiple immune checkpoint proteins may underlie resistance to anti-PD-1 monotherapy in immune-hot tumors. Multi-omic analysis identifies three molecular subtypes with high potential for treatment with CDK inhibitors, anti-EGFR antibody therapy, and immunotherapy, respectively. Altogether, proteogenomics provides a systematic framework to inform HNSCC biology and treatment.

Graphical Abstract

eTOC Blurb

Huang et al. report a proteogenomic study on 108 HPV-negative head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCCs). In addition to creating a comprehensive resource for pathogenic insights, multi-omic analysis identifies therapeutic hypotheses that may inform more precise approaches to treatment.

Introduction

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) is the sixth most common epithelial malignancy worldwide (Bray et al., 2018) and can be broadly classified into human papillomavirus (HPV)-associated (HPVpos) and HPV-negative (HPVneg) subtypes. Most HNSCC patients are treated with surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy. Targeted agents, including an EGFR monoclonal antibody (mAb) inhibitor and two PD-1 inhibitors, have been approved by FDA for HNSCC treatment, but overall response rates have been moderate (Baselga et al., 2005; Burtness et al., 2005; Herbst et al., 2005; Seiwert et al., 2016; Vermorken et al., 2008; Vermorken et al., 2007). Recently, the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and other studies have defined the genomic landscape and transcriptomic subtypes of HNSCC (Cancer Genome Atlas, 2015; Chung et al., 2004; Keck et al., 2015; Walter et al., 2013). However, a complete understanding of how genetic aberrations drive tumor phenotypes remains elusive, and translation of genomic and transcriptomic findings into improved HNSCC treatment has been limited.

By integrating mass spectrometry (MS)-based proteomics with genomics and transcriptomics, we performed an integrated proteogenomic characterization of 108 HPVneg HNSCCs. We focused on HPVneg HNSCCs because they account for 75% of all HNSCCs and have distinct molecular profiles and significantly worse prognosis compared to HPVpos tumors (Kreimer et al., 2005). Our study systematically catalogs HPVneg HNSCC-associated proteins, phosphosites, and signaling pathways. Proteogenomic integration provides functional insights into genomic aberrations, with practical implications for precision treatment of patients with HPVneg HNSCC.

Results

Proteogenomic Profiling

We prospectively collected 110 treatment-naïve primary HNSCC tumors and matched blood samples (Table S1), and 66 tumors had matched normal adjacent tissues (NATs). Homogenized samples were aliquoted for molecular profiling using whole-exome sequencing (WES), whole-genome sequencing (WGS), methylation array, RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), microRNA sequencing (miRNA-seq), and isobaric tandem mass tag (TMT) labeling-based global and phosphoproteomics (Figure 1A). One sample with evidence of HPV infection by RNA-seq was removed from downstream analysis (Figure S1A). The cohort was 87% male and tumor sites were predominantly from the oral cavity and larynx (44.5% each). Consistent with self-reporting, genomics-based smoking inference associated 70% of the patients with strong evidence of smoking (Figure S1B-C).

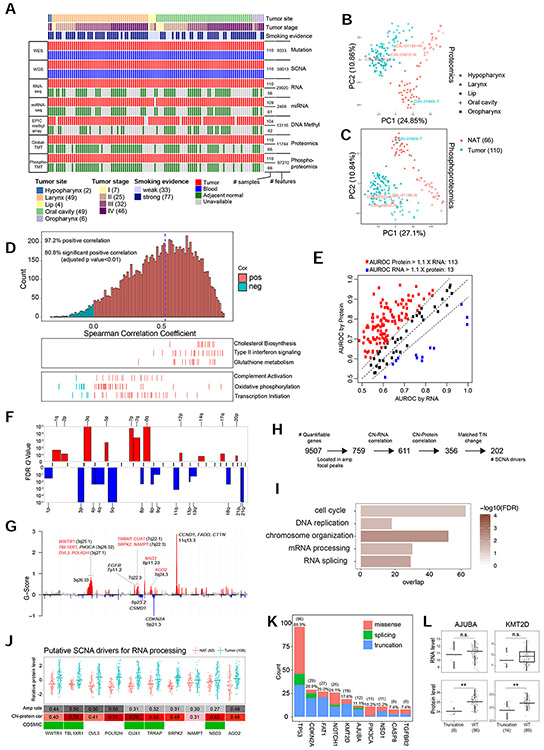

Figure 1. Proteogenomic profiling and impact of genetic aberrations on proteins.

(A) Cohort clinical features and omic data generation. (B) Global proteomics and (C) peptide-level phosphoproteomics PCA plots. (D) Gene-wise mRNA-protein correlation and pathway enrichment. (E) Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) for KEGG pathway membership prediction using RNA and protein data. Red and blue indicate pathways with >10% difference between the two. (F) Arm-level SCNAs. (G) Focal-level SCNAs with known drivers and RNA processing genes (red) annotated. (H) Prioritization of genes in focal amplification peaks. (I) GO terms enriched for prioritized SCNA drivers (Fisher’s exact test). (J) Protein abundance of RNA processing genes in tumors and NATs, annotated with amplification rate, copy number-protein correlation (Pearson’s correlation), and presence (green) in the COSMIC Cancer Gene Census. (K) Mutation frequency and type for the most frequently mutated genes. (L) Comparisons of RNA and protein levels for AJUBA and KMT2D between samples with truncating mutations and wild-type (WT) samples. **p<0.01, Student’s t-test. n.s., not significant. Numbers in parentheses represent the sample sizes for the involved groups. See also Figure S1 and Table S1-2.

Proteomic analysis identified 11,744 proteins. Phosphoproteomic analysis identified 97,210 phosphopeptides, covering 56,959 confidently localized phosphosites from 8,133 genes, including 81% on serine, 16% on threonine, and 3% on tyrosine. Replicate samples showed high measurement reproducibility across the TMT plexes, and there were no observable batch effects by TMT plex (Figure S1D-G). Unsupervised principal component analysis (PCA) of both proteomic and phosphoproteomic data separated tumor samples from NATs (Figure 1B-C). One tumor and three NAT samples with questionable tumor/NAT identity in data quality control (labeled in Figure 1B-C) were confirmed by pathological inspection and removed from downstream analysis.

For the 108 tumors, the median gene-wise Spearman’s correlation between protein and RNA abundance was 0.52, and the median sample-wise correlation was 0.43. Genes involved in forming large protein complexes, such as those related to complement activation, oxidative phosphorylation, and transcription initiation, showed lower protein-RNA correlation (Figure 1D). Protein data substantially outperformed RNA data in co-expression-based gene function prediction (Figure 1E), suggesting a critical role for protein-level regulation in determining gene functions.

Impact of Genetic Aberrations on Cognate Proteins

Somatic copy number alteration (SCNA) analysis identified arm level amplifications and deletions (Figure 1F). Focal peaks included amplifications of 3q26.33, 7p11.2, 7q22.3, 8p11.23, and 11q13.3 and deletions of 8p23.2 and 9p21.3, among others (Figure 1G). The strongest focal alteration was observed at 11q13.3. Some of these focal SCNA hotspots were also associated with structural variation events (Figure S1H and Table S2).

By filtering for correlated copy number (CN), mRNA, and protein levels across tumor samples and concordant protein level changes between paired tumor and NAT samples, we prioritized 202 putative SCNA drivers, including well-established PIK3CA, EGFR, CCND1, and CTTN, from a total of 759 quantifiable genes in the focal amplicons (Figure 1H-G, Table S2). The prioritized genes showed higher essentiality in HPVneg HNSCC cell lines in a genome-wide genetic perturbation screen (Tsherniak et al., 2017) (Figure S1I). Enrichment analysis associated the prioritized genes with cell cycle, DNA replication, chromosome organization, mRNA processing, and RNA splicing (Figure 1I). Amplification of the RNA processing genes (Figure 1G) has not been linked to HNSCC tumorigenesis previously, but some (WWTR1, TBL1XR1, CUX1, TRRAP, NSD3) are known cancer genes (Figure 1J).

Frequently mutated genes in this cohort (Figure 1K) were consistent with those in TCGA HPVneg HNSCCs, and we assessed the impact of mutations on cognate gene products. Missense mutations in TP53 were associated with increased p53 mRNA and protein abundance (Figure S1J), suggesting that certain TP53 mutations might endow oncogenic gain-of-function to this protein. Several frequently mutated genes had a substantial proportion of truncating mutations (Figure 1K), which typically induce nonsense-mediated decay (NMD) of cognate transcripts. Interestingly, truncating mutations in KMT2D and AJUBA were associated with reduced protein but not mRNA abundance (Figure 1L). Most of the truncating variants in these two genes may escape NMD according to the NMD rules (Lindeboom et al., 2016) (Table S2). Thus, proteomic data were crucial to support the tumor suppressor role of these genes.

DNA methylation of 91 genes was associated with both reduced mRNA and protein abundance in tumors (Table S2). These genes included several putative tumor suppressor genes whose expression was reported to be regulated by promoter methylation in other cancer types, such as NEFM (Calmon et al., 2015), MGMT (Rivera et al., 2010), GLDC (Min et al., 2016), and CHFR (Brandes et al., 2005).

Proteomic Alterations Associated with Tumorigenesis and Prognosis

We compared 63 tumors vs paired NATs to identify HNSCC-associated alterations in transcripts (mRNA, miRNA, and circRNA), proteins, and phosphosites (Table S3). Here we focus on results from the analysis of proteins and phosphosites quantified in ≥50% of the pairs. For proteins, 3,355 (35%) were significantly increased and 3,163 (33%) were significantly decreased in tumors (adjusted p<0.01, Wilcoxon signed-rank test, Figure 2A). The 104 proteins increased by >2-fold were enriched in biological processes such as protein hydroxylation, leukocyte migration, cell chemotaxis, and angiogenesis, whereas the 488 decreased proteins were enriched in acute inflammatory response, platelet degranulation, muscle system process, and fatty acid metabolic process (adjusted p<0.01, Fisher’s exact test, Table S3). After controlling for epithelium content in a multivariate model, 63 out of the 104 remained significantly elevated by >2-fold (Figure S2A, Table S3), and over two-thirds showed above average abundance of all proteins (Figure S2B). Among the 63, 22 are secretable and could serve as putative salivary biomarkers, seven can be targeted by FDA-approved drugs, and one is a cancer/testis (C/T) antigen (Figure 2B, Table S3). Notably, KIT, CAMP, and other highly increased proteins such as DEFA3, DEFA1B, CRTAP, and CLCNKA had decreased mRNA in tumors (Figure 2C, Figure S2C). Elevated tumor expression was supported by data-independent acquisition (DIA) proteomics (Figure S2D. I). Immunohistochemistry (IHC) data from the Human Protein Atlas (HPA) provided further independent validation for a subset of proteins (Figure S2E).

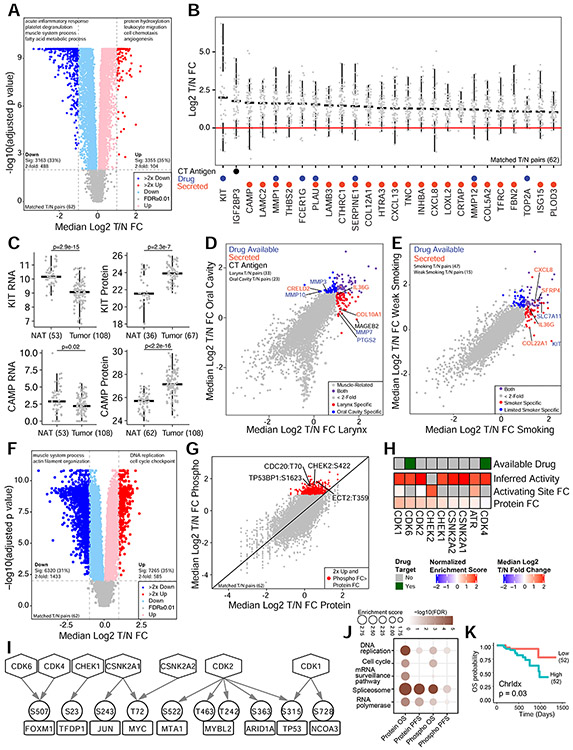

Figure 2. Proteomic alterations associated with tumorigenesis and prognosis.

(A) Protein abundance differences between tumors and NATs (Wilcoxon signed-rank test). Representative GO terms for 2-fold increased and decreased proteins are listed. (B) Abundance fold changes (FC) for selected highly elevated proteins annotated with potential clinical utilities. (C) Comparisons of RNA and protein levels for KIT and CAMP between tumors and NATs, Student’s t-test. (D) Comparison of protein changes in two anatomic sites. Dot colors indicate shared or site-specific elevations, and font colors indicate different types of clinical utilities. (E) Comparison of protein changes in tumors with strong and weak smoking evidence, colored as panel D. (F) Phosphosite abundance differences between tumors and NATs (Wilcoxon signed-rank test). Representative GO terms for proteins with 2-fold increased or decreased phosphosites are listed. (G) Comparison of abundance changes between phosphosites and their corresponding proteins. (H) Kinases with increased activity inferred from phosphorylation of its substrates (normalized enrichment score) or increased phosphorylation of its activating site. (I) Increased phosphorylation (circle) on transcription factor substrates (rectangle) of kinases (hexagon) with increased activity. All transcription factors had increased inferred activity from the RNA targets. (J) The common pathways enriched with proteins or phosphoproteins associated with OS or PFS (Fisher’s exact test). (K) Kaplan-Meier plot comparing OS for patients stratified by the median Chrldx score, logrank test. Numbers in parentheses represent the sample sizes for the involved groups. See also Figure S2 and Table S3.

Most proteins behaved similarly in the tumor vs NAT comparison whether derived from larynx or oral cavity (Figure 2D). However, 261 proteins, many muscle-related, were decreased specifically in oral cavity tumors, likely due to higher levels of muscle tissue in oral cavity NATs compared to larynx NATs. Several proteins with potential clinical utility were increased in a particular site (Figure 2D), including MAGEB2, PTGS2, MMP7, COL10A1, and IL36G in larynx (blue dots), and MMP3, MMP10, and CRELD2 in oral cavity (red dots). When grouped based on smoking evidence, tumors with strong smoking evidence showed specific increase of four secretable proteins (CXCL8, SFRP4, IL36G, COL22A1) and two targets of approved drugs (KIT, SLC7A11) (Figure 2E). The highly specific overexpression of KIT in tumors with strong smoking evidence explained the large variation of protein fold change observed for KIT across all tumors (Figure 2B).

For phosphosites, 7,265 (35%) were significantly increased and 6,320 (31%) were significantly decreased in tumors vs NATs (adjusted p<0.01, Wilcoxon signed-rank test, Figure 2F). Proteins with a phosphosite change >2-fold were enriched in biological processes such as DNA replication and cell cycle checkpoint, whereas proteins with a phosphosite change decreased by >2-fold were enriched in muscle system process and actin filament organization. Among the 559 phosphosites increased by >2-fold with stronger changes than in the corresponding protein (Figure 2G), only 8% had known functional annotations. Of these, 30% were involved in cell cycle regulation, including a site on the essential mitotic regulator CDC20 (Hein et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2015). An additional 12% were involved in cytoskeleton reorganization, including ECT2 T359, which contributes to tumor cell invasion (de Cárcer et al., 2017; Justilien et al., 2011). TP53BP1 S1623, which inhibits DNA repair, was also highly phosphorylated (Benada et al., 2015). Differential phosphosite analysis identified only one hyperphosphorylated activating site on a kinase, CHEK2 (Lovly et al., 2008). Kinase activities were also inferred based on the levels of substrate phosphorylation. A total of nine kinases had significantly increased activity, including targets of approved inhibitors (CDK4 and CDK6) (Figure 2H). Using predicted substrates for kinases (Linding et al., 2007), we identified 12 more kinases with increased activity in tumors, including CHUK and IKBKB, which are targets of approved inhibitors (Figure S2F). Increased kinase activity was supported by phosphorylation of corresponding transcription factor substrates and, in turn, increased transcription factor activity inferred from their mRNA targets (Figure 2I, Table S3).

Survival analysis identified 263 proteins and 173 phosphoproteins significantly associated with overall survival (OS), and 162 proteins and 164 phosphoproteins significantly associated with progression-free survival (PFS) (nominal p<0.01, Table S3). OXSR1 and GPALPP1 remained significant for both after multiple test adjustment, and 8 phosphoproteins remained significant for OS (Figure S2G-H, adjusted p<0.2). Strikingly, poor prognosis associated proteins/phosphoproteins were enriched in pathways reported in Figure 1I for SCNA drivers, including DNA replication, cell cycle, and RNA processing (Figure 2J), suggesting a potential relationship between SCNA and adverse clinical outcome. Indeed, tumors with higher chromosome instability scores (ChrIdx score) tended to have shorter OS (Figure 2K) and PFS (Figure S2I).

Mutually Exclusive FAT1 Truncating Mutations and 11q13.3 Amplification Converge to Protein-level Actin Dysregulation

FAT1 encodes an atypical cadherin and is one of the most frequently mutated genes in this cohort (Figure 1K) and the TCGA cohort. Truncating mutations account for >70% of all FAT1 mutations in both cohorts, in sharp contrast to other cancer types (Figure S3A). By integrating copy number data, we further divided FAT1 mutations into four groups (Figure S3B, Table S4). Compared to WT FAT1, samples with FAT1 biallelic truncations showed reduced FAT1 protein and mRNA levels (p=3.4e-6 and p=1.5e-3, Student’s t-test, Figure S3C-D). Since samples with other types of FAT1 mutations showed intermediate and more variable mRNA and protein levels, we excluded them from downstream analyses to focus on the most frequent mutation type with the strongest cis effects.

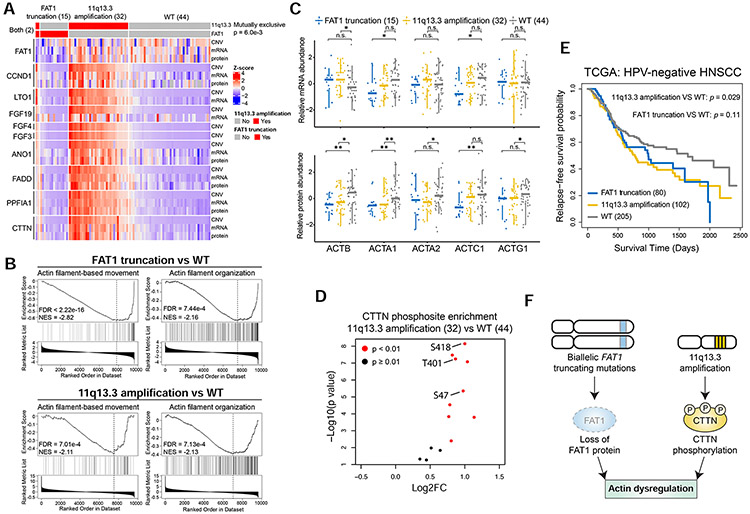

Mutual exclusivity was observed (p=6.0e-3, Fisher’s exact test) between FAT1 truncating mutation and 11q13.3 amplification (Figure 3A), the strongest focal SCNA in our cohort (Figure 1G). This was confirmed in TCGA HPVneg HNSCCs (p<0.001, Figure S3E). For all 9 protein coding genes in 11q13.3, amplification resulted in concordantly increased mRNA and protein abundance (Figure 3A).

Figure 3. Mutually exclusive FAT1 truncating mutations and 11q13.3 amplification converge to protein-level actin dysregulation.

(A) Heatmap visualizing multi-omic profiles of FAT1 and the nine coding genes in 11q13.3. (B) GSEA plots for actin-related pathways in FAT1 truncation or 11q13.3 amplification vs WT comparisons. (C) Relative mRNA and protein abundance in the FAT1 truncation, 11q13.3 amplification, and WT groups for five actin isoforms. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, Student’s t-test. n.s., not significant. (D) CTTN phosphosite abundance differences between the 11q13.3 amplification and WT groups (Student’s t-test). (E) Relapse-free survival in HPVneg HNSCC TCGA patients with FAT1 truncation or 11q13.3 amplification compared to WT (logrank test). (F) Proposed model explaining the mutual exclusivity between FAT1 truncating mutations and 11q13.3 amplification. Numbers in parentheses represent the sample sizes for the involved groups. See also Figure S3 and Table S4.

Mutual exclusivity may arise when two aberrations are functionally equivalent (Ciriello et al., 2012). Pathway enrichment analysis using proteomic data showed downregulation of proteins involved in actin dynamics in both FAT1 truncated and 11q13.3 amplified groups compared to the WT group (adjusted p<0.05, gene set enrichment analysis [GSEA], Figure 3B). Despite varying mRNA abundance of actin genes between groups, protein abundance for five actin genes was higher in the WT group (p<0.05, Student’s t-test, Figure 3C). In particular, beta-actin (encoded by ACTB), a non-muscle actin implicated in cell motility, structure and integrity (Drazic et al., 2018), was significantly downregulated at the protein level in both FAT1 truncated and 11q13.3 amplified groups despite upregulated mRNA. This finding was verified using DIA proteomic data (Figure S3F). These data suggest that FAT1 truncation and 11q13.3 amplification converge on regulating actin dynamics at the protein level.

Depletion of FAT1 has been causally linked to dysregulated actin organization at the cell periphery, looser cell association, and abrogated cell polarity (Tanoue and Takeichi, 2004). Phosphoproteomic data showed significantly elevated levels of CTTN phosphosites in 11q13.3 amplified samples compared to WT (Figure 3D). The most elevated phosphosite was CTTN S418, reported to alter cell motility and cytoskeletal rearrangement to promote tumor progression (MacGrath and Koleske, 2012). Although small sample size and short follow-up time precluded prognostic association in our cohort, patients harboring FAT1 truncation or 11q13.3 amplification had worse survival than those without either alteration in TCGA HPVneg HNSCCs (Figure 3E). These results suggest that both FAT1 truncation and 11q13.3 amplification drive poor prognosis, possibly through a common mechanism of modulating actin dynamics (Figure 3F), which provides an explanation for the mutual exclusivity between these frequent genomic aberrations in HPVneg HNSCC.

Proteogenomic Delineation of the Rb Pathway

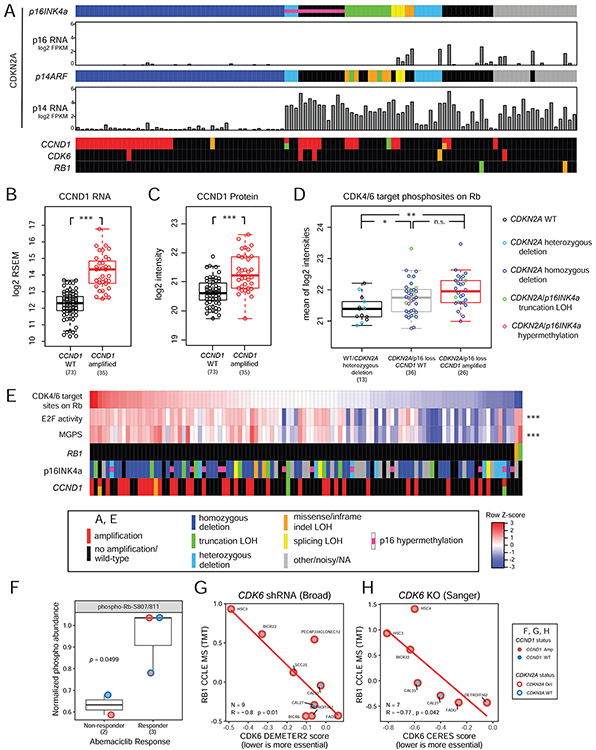

The most common genetic aberrations affected the cyclin D-CDK4/6-Rb pathway, including CDKN2A deletions (57%) and mutations (27%) and CCND1 amplifications (32%) (Figure 4A), all of which had comparable frequencies in the TCGA HPVneg HNSCCs. CDKN2A was hypermethylated in 13 tumors (12%), and hypermethylation was mutually exclusive with other loss of function alterations (Figures 4A and S4A-B, Table S4). Mutations in CDK6 (5%) and RB1 (2%) were also observed (Figure 4A).

Figure 4. Proteogenomic delineation of the cyclin D-CDK4/6-Rb pathway.

(A) Genetic and epigenetic aberrations in pathway genes. Impact of CDKN2A aberrations for two major isoforms, p16INK4a (p16) and p14ARF (p14), on respective transcript mRNA levels are shown separately. LOH: loss of heterozygosity. (B-C) Cis-effects of CCND1 amplification on RNA (B) and protein abundance (C). ***p<1e-4, Wilcoxon rank sum test, n=108. (D) Comparison of Rb phosphorylation levels (average of all CDK4/6 target sites) among three tumor groups. *p<0.05. **p<0.001, Wilcoxon rank sum test. (E) Heatmap comparing Rb phosphorylation, E2F activity, and the mean of cell cycle regulated genes (MGPS), with genomic aberrations annotated. ***p<1e-4, Pearson’s correlation with Rb phosphorylation. (F) Comparison of phospho-Rb-S807/811 in non-responsive and responsive HPVneg HNSCC PDX models to abemaciclib, Student’s t-test. (G-H) Associations between mass spectrometry (MS)-based Rb abundance and CDK6 essentiality scores derived from shRNA (DEMETER2, G) or CRISPR (CERES, H)-based genetic perturbations, respectively, in seven HPVneg HNSCC cell lines. R: Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Numbers in parentheses represent the sample sizes for the involved groups. See also Figure S4 and Table S4.

Homozygous deletion of CDKN2A led to loss of mRNA expression of both major isoforms, p16INK4a (p16) and p14ARF (p14), but other aberrations such as promoter hypermethylation primarily affected p16 (Figure 4A and S4B). Five CDKN2A mutations associated with loss of heterozygosity (LOH) altered p16 but not p14, and an additional six mutations resulted in truncation of p16 but only missense or in-frame indel changes in p14 (Figure S4A). Altogether, 68 tumors (63%) had genetic or epigenetic events predicted to disrupt p16 expression (tumors with homozygous deletion, p16 hypermethylation, or p16 truncation LOH in Figure 4A), which may explain widespread missing proteomic measurements for p16. CCND1 amplification was associated with increased levels of CCND1 RNA and protein in general, but not in all tumors as evidenced by overlap between the distributions of the amplified and WT groups (Figure 4B-C). To assess the impact of CDKN2A aberrations and CCND1 amplifications on CDK4/6-Rb signaling, we defined three groups: samples that were WT for pathway genes, including those with CDKN2A heterozygous deletion (n = 13), samples with p16 aberration affecting RNA expression but no CCND1 amplification (n = 36), and samples with both p16 aberration and CCND1 amplification (n = 26). Mean phosphorylation levels of the CDK4/6 target sites on Rb protein (Rb phosphosite score) were significantly higher in the 2nd and 3rd groups than in the 1st group (Figure 4D). However, many of the samples from the 2nd and 3rd groups had Rb phosphosite scores that were well within the range of the 1st group. The observation that CDKN2A and CCND1 aberrations did not always result in increased CCND1 protein and CDK4/6 activity was also seen in data from TCGA HPVneg HNSCCs (Figure S4C-E).

Rb phosphosite scores were significantly correlated with both E2F activity scores and multi-gene proliferation scores (MGPS) inferred from the RNA data (Pearson’s correlation = 0.50 and 0.47, p=4e-8 and 4e-7, respectively, Figure 4E). However, several samples with low Rb phosphosite scores had high E2F activity and MGPS, indicating cell cycle activation through other mechanisms besides CDK4/6 mediated phosphorylation. For example, the two samples with the lowest Rb phosphosite scores had high E2F activity and MGPS. These samples harbored RB1 mutations, potentially bypassing the need for CDK4/6 to phosphorylate Rb. While nearly all samples with high cell cycle activity had CDKN2A or CCND1 aberrations, a number of samples with these aberrations had low cell cycle activity. These observations suggest that Rb status is an effective and necessary indicator of CDK4/6-dependent cell cycle activity, which cannot be accurately predicted using genomic or transcriptomic markers.

To test the clinical relevance of Rb for CDK4/6 targeting, we analyzed data from HPVneg HNSCC PDXs treated with abemaciclib (Karamboulas et al., 2018), a CDK4/6 inhibitor in phase II clinical trials for HNSCC. While CCND1 and/or CDKN2A status did not separate response to abemaciclib, treatment responsive PDXs had elevated phospho-Rb-S807/811 signal (p=0.05, Student’s t-test) (Figure 4F). Moreover, CDK6 dependency was examined in HPVneg HNSCC cell lines from two independent genetic perturbation screens with associated molecular profiles from the cancer cell line encyclopedia (CCLE) (Behan et al., 2019; McFarland et al., 2018; Nusinow et al., 2020). Cell lines with higher levels of Rb protein, which was highly correlated with the Rb phosphosite score in our dataset (Spearman rho = 0.89, p<0.0001), were more sensitive to genetic depletion of CDK6 (p<0.05, Pearson’s correlation, Figure 4G-H). Taken together, these results support the hypothesis that phospho- or total Rb may serve as markers for CDK4/6 inhibitors in HPVneg HNSCC.

Two Modes of EGFR Activation

We analyzed our data to gain insights into the poor response of HNSCC patients to EGFR inhibition. EGFR mutations were identified in only three tumors, and none were hotspot mutations. Moreover, no samples harbored the EGFR VIII fusion variant. However, 49 samples showed EGFR amplification (CN log2 ratio > 0.1), and six had high amplification (CN log2 ratio > 1) (Figure 5A). EGFR CN was significantly associated with mRNA and protein abundance, overall phosphorylation level of EGFR, and phosphorylation levels of activation sites Y1110, Y1172, and Y1197 (Figure 5A-B). Thus, EGFR amplification is associated with EGFR activation.

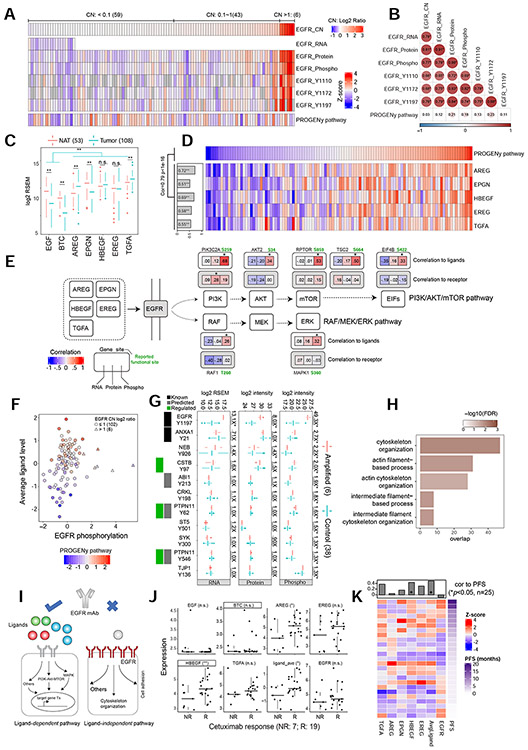

Figure 5. Proteogenomic characterization of EGFR ligand-dependent and -independent pathways.

(A) Heatmap comparing EGFR multi-omics profiles and the inferred PROGENy EGFR pathway activity and (B) their Pearson’s correlation coefficients. *p<0.01. (C) EGFR ligand mRNA abundance in tumors and NATs. **p < 0.001, Student’s t-test. (D) Pearson’s correlation between EGFR pathway activity and mRNA abundance of individual ligands. (E) For genes in the ligand-dependent pathways downstream of EGFR, the Pearson’s correlations between each omics feature and average ligand abundance (correlation to ligands) or EGFR abundance (correlation to receptor) are shown. *p < 0.01. Reported functional sites are colored green. (F) Relationship between PROGENy EGFR pathway activity (color gradients) and average ligand abundance or EGFR phosphorylation level. The six triangles represent samples with the high EGFR amplification. (G) Abundance comparisons between amplified samples and controls for 11 tyrosine phosphosites and cognate mRNA and proteins. Green box indicates known regulation by EGFR, black and gray indicate known and predicted EGFR substrates, respectively. Numbers on the side indicate fold changes. *p<0.01, Student’s t-test. (H) GO biological processes enriched with proteins with EGFR CN-associated phosphorylation (Fisher’s exact test). (I) Diagram depicting two modes of EGFR activation with implications for EGFR mAb therapies. (J) Comparisons between non-responsive (NR) and responsive (R) HPVneg HNSCC PDX models to Cetuximab treatment for average ligand (ligand_ave), individual ligands, and EGFR mRNA abundance. *p<0.05; **p<0.01 Student’s t-test. (K) Spearman’s correlations between mRNA abundance and PFS using data from a clinical trial testing panitumumab in HNSCC patients. Numbers in parentheses represent the sample sizes for the involved groups. See also Figure S5 and Table S5.

We inferred EGFR pathway activity based on mRNA expression data using PROGENy (Schubert et al., 2018). Unexpectedly, the inferred pathway activity showed no or weak correlations with EGFR alterations (Pearson’s correlation = 0.03 - 0.23, Figure 5A-B). In contrast, except for the two with very low mRNA abundance in tumors (Figure 5C), all EGFR ligands (Singh et al., 2016) showed strong correlations with inferred pathway activity (Pearson’s correlation = 0.51 – 0.72, Figure 5D). These observations were fully recapitulated in data from TCGA HPVneg HNSCCs (Figure S5A-D). Moreover, phosphoproteomics quantified several phosphosites on proteins involved in the PI3K/Akt/mTOR and the RAF/MEK/ERK pathways, two primary downstream pathways of EGFR (Wee and Wang, 2017). These phosphosites, including several key functional sites such as PIK3C2A S259 (Margaria et al., 2019), RPTOR S859 (Wang et al., 2009) and EIF4B S422 (Shahbazian et al., 2006), showed strong correlations with EGFR ligands, independent of the mRNA and protein expression of the host genes (Figure 5E). Conversely, none were significantly correlated with EGFR protein abundance. Thus, both transcriptomic and phosphoproteomic data suggest that the EGFR ligands, instead of the receptor, are the rate-limiting factors for EGFR pathway activity.

To identify signaling changes associated with EGFR amplification, which did not result in increased EGFR pathway activity but seemed to enhance EGFR phosphorylation in a ligand-independent manner (Figure 5F), we compared phosphoproteomic profiles between the six samples with high EGFR amplification and 38 other samples with similar chromosomal instability (ChrIdx score >3) (Figure S5E). This analysis identified 297 phosphosites with significantly higher phosphorylation in the EGFR amplification group (p<0.01, Student’s t-test), and 212 phosphosites showed stronger changes than at the RNA or protein level, suggesting these are bona fide phosphorylation changes and not due to differential gene expression or cell type composition (Table S5). The 11 tyrosine sites with significantly increased phosphorylation (Figure 5G) included five known or predicted EGFR substrates (EGFR Y1197, ANXA1 Y21, PTPN11 Y546, PTPN11 Y62, and ABI1 Y213). Additionally, PTPN11 Y546, PTPN11 Y62, and CSTB Y97 are reported to be regulated by EGFR in the PhosphoSitePlus database. Proteins harboring the 212 sites were enriched in cytoskeleton organization, actin filament, and intermediate filament junction related pathways (adjusted p<0.01, Fisher’s exact test, Figure 5H), suggesting a role for EGFR in modulating intercellular junctions and cell motility, as previously reported (Klymkowsky and Parr, 1995; Stallaert et al., 2018).

Since our data suggest that EGFR amplification activates EGFR in a ligand-independent manner, and EGFR mAbs function primarily by binding to the EGFR extracellular domain to prevent ligand-induced pathway activity (Harding and Burtness, 2005; Messersmith and Hidalgo, 2007), EGFR ligand abundance, rather than EGFR amplification or overexpression, should be used to select HNSCC patients for treatment with anti-EGFR mAbs (Figure 5I). Indeed, utilizing data from an HNSCC PDX study with treatment response to an EGFR mAb, cetuximab (Klinghammer et al., 2017), we found that EGFR ligands, not the receptor, showed significantly higher expression in responders than non-responders (Figure 5J). Furthermore, in a clinical trial testing another EGFR mAb, panitumumab, in HNSCC patients (Siano et al., 2018), we found that EGFR ligand abundance, but not receptor abundance, significantly correlated with PFS (Figure 5K).

Immuno-proteogenomic Analysis Reveals Immunosuppressive SCNAs

To gain a deeper understanding of immune evasion and resistance to PD-1 inhibitors in HNSCC, we performed an immuno-proteogenomic analysis. Tumors showed a wide range of immune cell infiltration levels as consistently quantified by ESTIMATE immune score (Yoshihara et al., 2013), CD3 IHC staining, and CD3 proteomic data (Figure 6A). Higher immune cell infiltration was not linked to any anatomic sites but was associated with lower clinical stage, less smoking, and better prognosis (Figure 6B, Figure S6A-B). In silico deconvolution using xCell (Aran et al., 2017) showed that both cytotoxic immune cells (e.g., CD8 T cells and M1 macrophages) and immunosuppressive cells (e.g., Tregs and M2 macrophages) were enriched in tumors with high levels of immune cell infiltration. In these immune-hot tumors, both cytotoxic immune enzymes and immunosuppressive proteins were overexpressed at the protein and/or mRNA levels (Figure 6A), with high correlations observed across immune inhibitory genes (Figure 6C). These data may explain the moderate response rate to single-agent pembrolizumab treatment in PD-L1 positive HNSCCs (Seiwert et al., 2016) and suggest combinatorial checkpoint inhibition as a logical proposition to increase treatment efficacy.

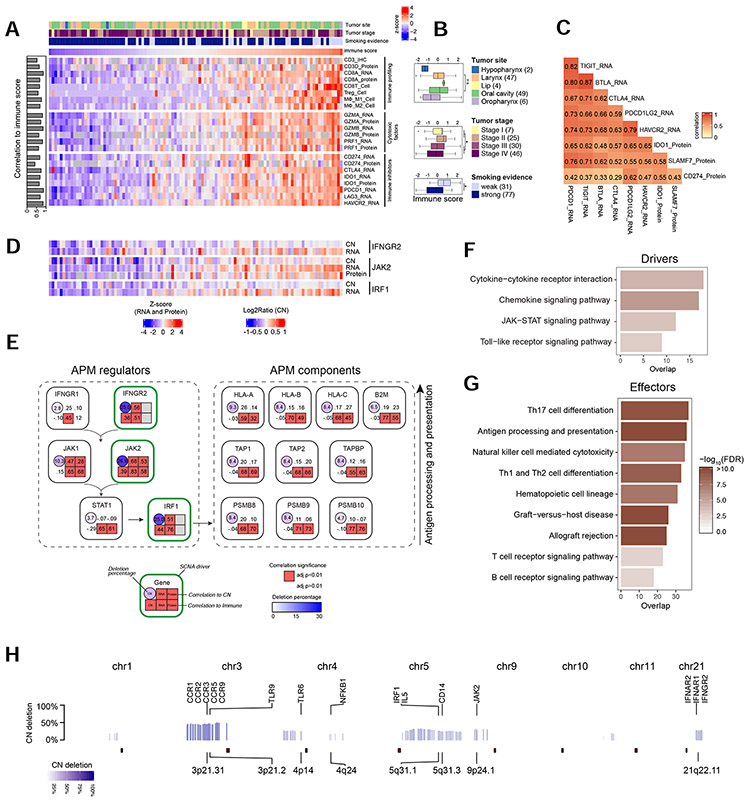

Figure 6. Immuno-proteogenomic analysis reveals immunosuppressive SCNA drivers.

(A) Pearson’s correlations between ESTIMATE immune score and proteogenomic profiles of immune infiltration, cytotoxic factors, and immune inhibitors. (B) Comparisons of the immune score across clinical attributes (*p<0.01, Student’s t-test). (C) Correlations among immune checkpoints and suppressors. (D) Copy number (CN), mRNA abundance, and protein abundance of three SCNA driver genes. (E) Diagram showing the information flow from antigen processing and presenting machinery (APM) regulators to APM components. The top row for each gene shows the cis-effect of CN on RNA and protein abundance, and the bottom row shows the correlation between immune score and each omics type. (F) Pathways enriched for immune-associated genes whose expression was suppressed by SCNA (i.e., immunosuppressive SCNA drivers). (G) Pathways enriched for immune-associated genes whose expression was not associated with SCNA (i.e., effectors of the immune-suppressive CN deletions). (H) The distribution of immunosuppressive SCNAs across the genome. Selected immune genes are highlighted. Numbers in parentheses represent the sample sizes for the involved groups. See also Figure S6 and Table S6.

Next, we sought to identify tumor intrinsic determinants of low immune infiltration in immune-cold tumors. We observed negative correlations between immune cell infiltration and either tumor mutational burden or protein abundance of quantified C/T antigens (Figure S6C). Moreover, proteomics-supported neoantigens (Wen et al., 2020) (Table S6) showed little correlation to immune cell infiltration (Figure S6C). Thus, the low immune infiltration was not driven by a lack of tumor antigen sources. Instead, we found significantly reduced expression of multiple components and regulators of the antigen presentation machinery (APM) pathway at both mRNA and protein levels in immune-cold tumors (Figure S6D-E). Few mutations in APM genes and their regulators were identified in our cohort (Figure S6F), but frequent somatic CN deletions (>25%) were found in APM regulators IFNGR2, JAK2, and IRF1 (Figure S6G). CN levels of these genes correlated strongly with mRNA and protein levels when data were available, and these genes further showed strong correlation with immune infiltration at all molecular levels (Figure 6D-E), suggesting a causal contribution of these gene deletions to APM deficiency and low immune infiltration (i.e., ‘SCNA drivers’). In comparison, APM components showed significant correlation with immune infiltration at the gene expression, but not CN level, indicating that the changes occurred in trans (i.e., “SCNA effectors”). Consistent with the model depicted in Figure 6E, gene regulatory network analysis using VIPER (Alvarez et al., 2016) identified STAT1 as the central transcription factor regulating immune activity.

Expanding the APM-focused analysis to a genome-wide search identified 294 putative SCNA drivers (Table S6) and 2,058 putative SCNA effectors. SCNA drivers were enriched in cytokine/chemokine receptor, JAK-STAT, and TLR pathways, all of which regulate immunogenicity or immune response within tumor cells (Figures 6F and S6H). By contrast, SCNA effectors were mostly involved in immune cytotoxicity, especially adaptive immune cell activation and function (Figure 6G). SCNA drivers were distributed widely across the genome (Figure 6H), including the most frequently deleted 3p region, which encodes chemokine/cytokine receptors and TLRs, and 9p24.1, which encodes JAK2, a key component of the JAK-STAT pathway. Genes deleted in 9p24.1 also include CD274 that encodes PD-L1, suggesting that PD-L1-mediated immune checkpoint is not needed in immune-cold HNSCCs. Our observations for both immune-cold and immune-hot tumors were supported by our reanalysis of transcriptomic data from TCGA HPVneg HNSCCs (Figure S6I-L), albeit at a lower sensitivity for detecting the driver CN pathway signals, suggesting that integrating proteomic data helpedprioritize driver CN events involved in immunogenicity.

Multi-omics Subtypes and Targeted Therapies

By integrating CN, RNA, miRNA, protein, and phosphopeptide data, an unsupervised clustering analysis grouped tumors into three clusters. Clusters I, II, and III were significantly associated with previously established classical, basal, and mesenchymal RNA subtypes (Walter et al., 2013), respectively (p<0.05, Fisher’s exact test, Figure 7A-B).

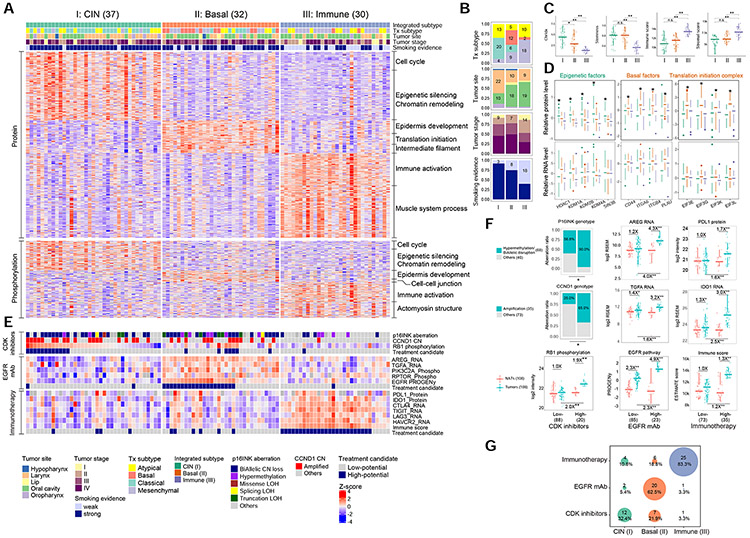

Figure 7. Integrated multi-omics subtypes and subtype-specific targeted therapies.

(A) Proteomic and phosphoproteomic profiles of the signature proteins and the enriched biological processes of the three integrated subtypes. (B) Sample distribution across different clinical attributes. (C) Comparisons of the three subtypes for four molecular phenotypes. *p<0.01, **p<0.001, Student’s t-test. (D) mRNA and protein levels of protein-specific gene signatures related to epigenetic, basal, and translation initiation factors for different subtypes. Each feature was tested for its differential abundance between the given subtype and the other two subtypes. *: adjusted p<0.01 for both comparisons, Student’s t-test. (E) Heatmap visualizing proteogenomic measurements of the suggested biomarkers for targeted therapies and candidacy for treatment with CDK inhibitors (upper), EGFR mAb (middle), and immune checkpoint blockade (bottom). (F) Comparisons of the proposed biomarkers between high-potential and low-potential tumors, and between each group of tumors and NATs. Numbers at the top denote fold changes. *p<0.01 **p<0.001. Student’s t-test. (G) The proportions of high-potential candidates for each target therapy in the three subtypes. Numbers in parentheses represent the sample sizes for the involved groups. See also Figure S7 and Table S7.

The classical, basal, and mesenchymal RNA subtypes have been characterized by overexpression of genes related to cell proliferation, epidermal development, and stromal infiltration, respectively (Walter et al., 2013). Proteomic and phosphoproteomic data not only confirmed these features but also provided new insights (Figures 7A and S7A-C, Table S7). Cluster I was associated with the larynx, strong smoking (Figure 7B, p<0.01, Fisher’s exact test), and high chromosome instability (CIN) (Figures 7C and S7D). Proteomic data, but not RNA-seq data, showed increased levels of multiple epigenetic regulators in this cluster (Figure 7D), supporting a suggested linkage between aberrant epigenetic activities and smoking and CIN in HNSCC (Ghantous et al., 2018; Papillon-Cavanagh et al., 2017). This cluster showed the worst prognosis (Figure S7E-F), which is consistent with the observation for the classical RNA subtype of HNSCC (Keck et al., 2015). Cluster II showed protein-level elevation of several basal factors (Figure 7D). Moreover, protein- and phosphorylation-specific elevation of eukaryotic translation initiation (EIF) complex members indicated higher translational activity in these tumors (Figures 7D and S7G). Both clusters I and II were associated with higher stemness (Figure 7C), likely due to aberrant epigenetic activity and basal-like factor activation, respectively (Malta et al., 2018). Cluster III was enriched with tumors with weak smoking evidence (p<0.01, Fisher’s exact test, Figure 7B). It was also associated with higher immune scores and, to a lesser degree, higher stromal scores (Figure 7C). Consistent with our observation, a more recent HNSCC subtyping study annotated the mesenchymal RNA subtype as “inflamed” (Keck et al., 2015). Notably, the atypical RNA subtype, which was enriched with HPVpos samples in the original study, collapsed to clusters I and III (Figure 7B), which was supported by their associations with relatively higher stemness cores and higher immune/stromal scores, respectively (Figure S7H). Taken together, our multi-omics subtyping identified three subtypes of HPVneg HNSCCs, which we named CIN, Basal, and Immune, respectively.

To examine the utility of these subtypes in guiding treatment selection, we evaluated their associations with our proposed biomarkers for targeted therapies in HNSCC (Figure 7E). The CIN subtype was associated with frequent genetic aberrations of CCND1 and CDKN2A and high CDK4/6 activity as indicated by Rb hyperphosphorylation, suggesting potential response to CDK4/6 inhibitors. The Basal subtype was characterized by high EGFR ligand expression (AREG and TGFA) and high EGFR pathway activity, suggesting potential response to EGFR mAb. The Immune subtype showed high expression of multiple immune checkpoint proteins, and thus may benefit from checkpoint blockade. For each treatment option, the high-potential tumors showed significantly higher levels of the biomarkers than the low-potential tumors and the matched NATs (p<0.01, Student’s t-test), whereas the latter two showed no or a less significant difference (Figure 7F). In total, 32% of the CIN tumors, 62% of the Basal tumors, and 83% of the Immune tumors had high potential for treatment with CDK inhibitors, EGFR mAb, and immunotherapy, respectively (Figure 7G).

Discussion

With several targeted therapies approved for the treatment of HNSCC and many more in development, the identification of accurate biomarkers to guide treatment selection is a major research priority (Santuray et al., 2018). Our study demonstrates the promise of proteogenomics in addressing this challenge. For EGFR targeted therapy, it is well acknowledged that EGFR amplification or overexpression cannot be used to predict response to EGFR mAbs in HNSCC (Ang et al., 2014; Burtness et al., 2005; Crombet et al., 2004; Psyrri et al., 2014). Our data suggest a new strategy of using EGFR ligand abundance to stratify patients for effective treatment with EGFR mAb. In addition, some tumors with EGFR ligand overexpression also harbor CCND1 and CDKN2A aberrations, which may render them resistant to anti-EGFR mAb monotherapy. Tumors with high EGFR amplification do not necessarily have high levels of EGFR ligands and may not respond to EGFR mAbs. However, these tumors show strong EGFR phosphorylation and thus could respond to small-molecule EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs). Consistent with this hypothesis, the combination of p16-negativity and EGFR amplification identified HNSCC patients that achieved a clinically meaningful benefit from afatinib, an EGFR TKI, in a phase III trial (Santuray et al., 2018).

For immunotherapy, immune-hot tumors concordantly overexpress multiple checkpoints and other immunosuppressive genes, which may partially explain the moderate response rate in PD-L1 positive HNSCCs to a single-agent pembrolizumab treatment (Seiwert et al., 2016). Moreover, there was no clinical improvement from combining durvalumab (PD-L1 antibody) and tremelimumab (CTLA-4 antibody) in unselected patients with relapsed/metastatic HNSCC in a phase III trial (Ferris et al., 2020). Profiling of multiple immune checkpoint proteins may allow more precise personalization of combination immunotherapy regimens, potentially leading to improved outcomes through accurate patient selection.

Multiple clinical trials are evaluating CDK4/6 inhibitors in HNSCC, but there are no established biomarkers to guide patient selection (Adkins et al., 2019). Rb phosphorylation status could be considered as a biomarker together with CCND1/CDKN2A genomic aberrations for future clinical trials of CDK4/6 inhibitors, whereas these genomic markers alone, or transcriptomic markers of E2F activity, may not accurately reflect CDK4/6 activity.

We identified new targets for therapeutic development, such as KIT, FCER1G, PLAU, SERPINE1, TOP2A, several MMPs, and several cell cycle and DNA damage-related kinases. In addition, multiple C/T antigens are recurrently overexpressed in tumors compared to NATs, including IGF2BP3, MAGEB2, KIF2C, CEP55, and NUF2 (Figure 2, Figure S6), and proteomics-supported neoantigens were predicted for 20.4% of the patients (Table S6). Both C/T antigens and neoantigens are promising immunotherapy targets.

We also generated new knowledge concerning HNSCC biology. Proteomics data prioritized copy number drivers and highlighted an oncogenic role for RNA processing factors in HNSCC tumorigenesis. Widespread deletion of immune modulatory genes may account for loss of immunogenicity and low immune infiltration in HNSCC. FAT1 was among the most frequently mutated genes in HNSCC. Previous studies have linked FAT1 mutations to the WNT and HIPPO pathways (Ciriello et al., 2012; Martin et al., 2018) or apoptosis (Kranz and Boutros, 2014), but none of these theories were supported by our data (Figure S3G). Instead, proteomic investigation of the mutually exclusive relationship between FAT1 truncating mutations and 11q13.3 amplifications revealed their functional convergence on dysregulated actin dynamics, which may underlie poor prognosis of tumors with these genetic aberrations.

In summary, this study extends our biological understanding of HPVneg HNSCC and generates therapeutic hypotheses that may serve as the basis for future preclinical studies and clinical trials toward molecularly guided precision treatment of this aggressive cancer type. Meanwhile, we have made the primary and processed datasets available in publicly accessible data repositories and portals, which will allow full investigation of this extensively characterized cohort by both the HNSCC and broader scientific communities. We also expect wide application of the demonstrated proteogenomics framework to future studies of HNSCC and other cancer types.

STAR METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead Contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Bing Zhang (bing.zhang@bcm.edu).

Materials Availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and Code Availability

Raw proteomics data files are hosted by the CPTAC Data Portal and can be accessed at: https://proteomics.cancer.gov/data-portal. Genomic and transcriptomic data files can be accessed via the Genomic Data Commons (GDC) Data Portal: https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov. Processed data utilized for this publication can be accessed via LinkedOmics: http://www.linkedomics.org.

Several customized coding software packages were generated as part of this study and have been referenced in the corresponding STAR Methods section and listed with links to the coding script in the Key Resources Table: software codes generated by the Cieslik laboratory for genomic analyses (CNVEX), by the Nesvizhskii laboratory for proteomic data processing (Philosopher and TMT-Integrator), and by the Zhang lab for data processing and neoantigen detection (NeoFlow and PepQuery).

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid | Alfa Aesar | Catalog: J63218 |

| Acetonitrile, Optima LC/MS | Fisher Chemical | A955-4 |

| Ammonium Hydroxide solution | Sigma | Catalog: 338818 |

| Aprotinin | Sigma | Catalog: A6103 |

| CD3 antibody (polyclonal) | Agilent - Dako | #A0452 |

| DAB | Agilent - Dako | #K3468 |

| Dithiothreitol | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Catalog: 20291 |

| Envision+ System HRP labelled polymer, anti-Rabbit | Agilent - Dako | #K4002 |

| Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid | Sigma | Catalog: E7889 |

| Formic acid | Fisher Chemical | Catalog: A117-50 |

| Hydroxylamine solution | Aldrich | Catalog: 467804 |

| Iodoacetamide | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Catalog: A3221 |

| Iron (III) chloride | Sigma | Catalog:451649 |

| Leupeptin | Roche | Catalog: 11017101001 |

| Lysyl endopeptidase, aass spectrometry grade | Wako Chemicals | Catalog: 125-05061 |

| Ni-NTA agarose beads | QIAGEN | Catalog: 30410 |

| PUGNAc | Sigma | Catalog: A7229 |

| Phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride | Sigma | Catalog: 93482 |

| Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail 2 | Sigma | Catalog: P5726 |

| Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail 3 | Sigma | Catalog: P0044 |

| Reversed-phase C18 SepPak | Waters | Catalog: WAT054925 |

| Sequencing grade modified trypsin | Promega | Catalog: V511X |

| Sodium chloride | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Catalog: sc-295833 |

| Sodium fluoride | Sigma | Catalog: S7920 |

| TMT11-131C label reagent | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Catalog: A34807 |

| Tandem mass tags – 10plex | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Catalog: 90406 |

| Trifluoroacetic acid | Sigma | Catalog: 302031 |

| Tris(hydroxymethyl)amino methane | Invitrogen | Catalog: AM9855G |

| Urea | Sigma | Catalog: U0631 |

| Water, Optima LC/MS | Fisher Chemical | W6-4 |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| TruSeq Stranded Total RNA Library Prep Kit with Ribo-Zero Gold | Illumina | Catalog: RS-122-2301 |

| Infinium MethylationEPIC Kit | Illumina | Catalog: WG-317-1003 |

| Nextera DNA Exosome Kit | Illumina | Catalog: 20020617 |

| KAPA Hyper Prep Kit, PCR-free | Roche | Catalog: 07962371001 |

| BCA Protein Assay Kit | ThermoFisher Scientific | Catalog: 23225 |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| Software | Source | Identifier (i.e. links) |

| Bowtie (v1.1.1) | (Langmead et al., 2009) | https://sourceforge.net/projects/bowtie-bio/files/bowtie/ |

| Bowtie2 (v2.3.3) | (Langmead and Salzberg, 2012) | http://bowtie-bio.sourceforge.net/bowtie2/index.shtml |

| BWA (v0.7.17-r1188) | (Li and Durbin, 2009) | http://bio-bwa.sourceforge.net/ |

| cBioPortal | (Cerami et al., 2012; Gao et al., 2013) | https://www.cbioportal.org |

| CIRI (v2.0.6) | (Gao et al., 2015) | https://sourceforge.net/projects/ciri/ |

| CNVEX | Marcin Cieslik Lab | https://github.com/mctp/cnvex |

| Customprodbj | (Wang and Zhang, 2013) | https://github.com/bzhanglab/customprodbj |

| EricScript v0.5.5 | (Benelli et al., 2012) | https://sites.google.com/site/bioericscript/ |

| ESTIMATE | (Yoshihara et al., 2013) | https://bioinformatics.mdanderson.org/public-software/estimate/ |

| germlinewrapper v1.1 | Li Ding Lab | https://github.com/ding-lab/germlinewrapper |

| GISTIC2 | (Mermel et al., 2011) | https://www.genepattern.org/modules/docs/GISTIC_2.0 |

| GSVA | (Hänzelmann et al., 2013) | https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/GSVA.html |

| lmerTest | (Kuznetsova et al., 2017) | https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/lmerTest/index.html |

| INTEGRATE v0.2.6 | (Zhang et al., 2016) | https://sourceforge.net/projects/integrate-fusion/ |

| iProFUN | (Song et al., 2019) | https://github.com/WangLab-MSSM/iProFun |

| LinkedOmics | (Vasaikar et al., 2018) | http://linkedomics.org |

| Manta v1.6.0 | (Chen et al., 2016) | https://github.com/Illumina/manta |

| MoonlightR | (Colaprico et al., 2020) | http://bioconductor.org/packages/MoonlightR/ |

| MSFragger-20190628 | (Kong et al., 2017) | http://msfragger.nesvilab.org/ |

| MS-GF+ | (Kim and Pevzner, 2014) | https://github.com/MSGFPlus/msgfplus/ |

| MuTect v1.1.7 | (Cibulskis et al., 2013) | https://github.com/broadinstitute/mutect |

| NeoFlow | (Wen et al., 2020) | https://github.com/bzhanglab/neoflow |

| NetworKIN | (Linding et al., 2008) | https://networkin.info |

| OmicsEV | Bing Zhang lab | https://github.com/bzhanglab/OmicsEV |

| OmicsOne | Hui Zhang Lab | https://github.com/huizhanglab-jhu/OmicsOne |

| PepQuery | (Wen et al., 2019) | http://pepquery.org/ |

| PeptideProphet | (Keller et al., 2002) | http://tools.proteomecenter.org/wiki/index.php?title=Main_Page |

| PDV | (Li et al., 2019) | https://github.com/wenbostar/PDV |

| Philosopher-v1.6.0 | Alexey Nesvizhskii lab | https://philosopher.nesvilab.org/ |

| Pindel v0.2.5 | (Ye et al., 2009) | https://github.com/genome/pindel |

| ProteinProphet | (Nesvizhskii et al., 2003) | http://tools.proteomecenter.org/wiki/index.php?title=Main_Page |

| PTMProphet | (Shteynberg et al., 2019) | http://tools.proteomecenter.org/wiki/index.php?title=Main_Page |

| QuickMIRSeq | (Zhao et al., 2017) | https://sourceforge.net/projects/quickmirseq/ |

| RSEM (v1.3.1) | (Li and Dewey, 2011) | https://deweylab.github.io/RSEM/ |

| Samtools (V1.1.0) | (Li et al., 2009) | https://github.com/samtools/samtools |

| SignatureAnalyzer | (Kim et al., 2016) | https://software.broadinstitute.org/cancer/cga/msp |

| somaticwrapper v1.5 | Li Ding Lab | https://github.com/ding-lab/somaticwrapper |

| STAR-Fusion v1.5.0 | (Haas et al., 2019) | https://github.com/STAR-Fusion/STAR-Fusion |

| Strelka v2.9.2 | (Kim et al., 2018) | https://github.com/Illumina/strelka |

| Sumer | (Savage et al., 2019) | https://github.com/bzhanglab/sumer |

| TCGAbiolinks | (Colaprico et al., 2016) | http://bioconductor.org/packages/TCGAbiolinks/ |

| TMT-Integrator-v1.0.9 | Alexey Nesvizhskii lab | http://tmt-integrator.nesvilab.org/ |

| VarScan v2.3.8 | (Koboldt et al., 2012) | https://dkoboldt.github.io/varscan/ |

| VIPER | (Alvarez et al., 2016) | http://califano.c2b2.columbia.edu/viper |

| VirusScan | (Cao et al., 2016) | https://github.com/ding-lab/VirusScan/tree/simplified |

| WebgestaltR | (Liao et al., 2019) | http://www.webgestalt.org/ |

| xCell | (Aran et al., 2017) | http://xcell.ucsf.edu/ |

| Deposited Data | ||

| cBioPortal | (Cerami et al., 2012) | https://www.cbioportal.org/ |

| CTDatabase | (Almeida et al., 2009) | http://www.cta.lncc.br |

| DoRothEA | (Garcia-Alonso et al., 2019) | https://github.com/saezlab/DoRothEA |

| Human Protein Atlas | (Uhlén et al., 2015) | https://www.proteinatlas.org |

| MSigDBv7.0 Hallmark gene sets | (Liberzon et al., 2015) | https://www.gsea-msigdb.org |

| PhosphoSitePlus | (Hornbeck et al., 2015) | https://www.phosphosite.org |

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Specimens and Clinical Data

Tumor and germline blood samples from 110 qualified cases were collected from 6 tissue source sites in strict accordance to the CPTAC-3 protocol. All patients provided written informed consent. Institutional review boards at tissue source sites reviewed protocols and consent documentation adhering to the CPTAC guidelines. Normal adjacent tissues were collected from 83 cases. This study contained predominantly males (87%) and the cases were collected from 7 different countries. Histopathologically-defined squamous cell carcinomas were considered for analysis, with an age range of 23-81. A complete set of clinical data were obtained from the tissue source sites and reviewed for correctness and completeness.

Sample Processing

The CPTAC Biospecimen Core Resource (BCR) at the Pathology and Biorepository Core of the Van Andel Research Institute in Grand Rapids, Michigan manufactured and distributed biospecimen kits to the Tissue Source Sites (TSS) located in the US, Europe, and Asia. Each kit contains a set of pre-manufactured labels unique for each specimen respective to TSS location, disease, and sample type that is used to track the specimens through the BCR to the CPTAC proteomic and genomic characterization centers.

Tissue specimens averaging 200 mg were snap-frozen by the TSS within a 30-minute cold ischemic time (CIT) (CIT average = 13 minutes) and an adjacent segment was formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) and H&E stained by the TSS for quality assessment to meet the CPTAC HNSCC requirements. Routinely, several tissue segments for each case were collected. Tissues were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen (LN2) then transferred to a LN2 freezer for storage until approval for shipment to the BCR.

Specimens were shipped using a cryoport that maintained an average temperature of under −140°C to the BCR with a time and temperature tracker to monitor the shipment. Receipt of specimens at the BCR included a physical inspection and review of the time and temperature tracker data for specimen integrity, followed by barcode entry into a biospecimen tracking database. Specimens were again placed in LN2 storage until further processing. Acceptable HNSCC tumor tissue segments were determined by TSS pathologists based on the percent viable tumor nuclei (> 80%), total cellularity (> 50%), and necrosis (< 20%). Segments received at the BCR were verified by BCR and Leidos Biomedical Research (LBR) pathologists and the percent of total area of tumor in the segment was also documented. Additionally, disease-specific working group pathology experts reviewed the morphology to clarify or standardize specific disease classifications and correlation to the proteomic and genomic data.

Specimens selected for this study were determined on the maximal percent in the pathology criteria and best weight. Specimens were pulled from the biorepository using an LN2 cryocart to maintain specimen integrity and then cryopulverized. The cryopulverized specimen was divided into aliquots for DNA (30 mg) and RNA (30 mg) isolation and proteomics (50 mg) for molecular characterization. Nucleic acids were isolated and stored at −80°C until further processing and distribution; cryopulverized protein material was returned to the LN2 freezer until distribution. Shipment of the cryopulverized segments used cryoports for distribution to the proteomic characterization centers and shipment of the nucleic acids used dry ice shippers for distribution to the genomic characterization centers; a shipment manifest accompanied all distributions for the receipt and integrity inspection of the specimens at the destination. The DNA sequencing was performed at the Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA and RNA sequencing was performed at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC. Material for proteomic analyses was sent to the Proteomic Characterization Center at Johns Hopkins University, Maryland, USA.

METHOD DETAILS

Genomics and Transcriptomics Profiling Experiments

Sample Processing for Genomic DNA and Total RNA Extraction

Our study sampled a single site of the primary tumor from surgical resections, due to the internal requirement to process a minimum of 125 mg of tumor issue and 50 mg of adjacent normal tissue. DNA and RNA were extracted from tumor and normal specimens in a co-isolation protocol using Qiagen’s QIAsymphony DNA Mini Kit and QIAsymphony RNA Kit. Genomic DNA was also isolated from peripheral blood (3-5 mL) to serve as matched germline reference material. The Qubit™ dsDNA BR Assay Kit was used with the Qubit® 2.0 Fluorometer to determine the concentration of dsDNA in an aqueous solution. Any sample that passed quality control and produced enough DNA yield to go through various genomic assays was sent for genomic characterization. RNA quality was quantified using the NanoDrop 8000 and quality was assessed using the Agilent Bioanalyzer. A sample that passed RNA quality control and had a minimum RIN (RNA integrity number) score of 7 was subjected to RNA sequencing. Identity match for germline, normal adjacent tissue, and tumor tissue was assayed at the BCR using the Illumina Infinium QC array. This beadchip contains 15,949 markers designed to prioritize sample tracking, quality control, and stratification.

Whole Exome Sequencing (WES)

Library Construction

Library construction was performed as described in (Fisher et al., 2011), with the following modifications: initial genomic DNA input into shearing was reduced from 3 μg to 20-250 ng in 50 μL of solution. For adapter ligation, Illumina paired-end adapters were replaced with palindromic forked adapters, purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies, with unique dual-indexed molecular barcode sequences to facilitate downstream pooling. Kapa HyperPrep reagents in 96-reaction kit format were used for end repair/A-tailing, adapter ligation, and library enrichment PCR. In addition, during the post-enrichment SPRI cleanup, elution volume was reduced to 30 μL to maximize library concentration, and a vortexing step was added to maximize the amount of template eluted.

In-solution Hybrid Selection

After library construction, libraries were pooled into groups of up to 96 samples. Hybridization and capture were performed using the relevant components of Illumina's Nextera Exome Kit and followed the manufacturer’s suggested protocol, with the following exceptions. First, all libraries within a library construction plate were pooled prior to hybridization. Second, the Midi plate from Illumina’s Nextera Exome Kit was replaced with a skirted PCR plate to facilitate automation. All hybridization and capture steps were automated on the Agilent Bravo liquid handling system.

Preparation of Libraries for Cluster Amplification and Sequencing

After post-capture enrichment, library pools were quantified using qPCR (automated assay on the Agilent Bravo) using a kit purchased from KAPA Biosystems with probes specific to the ends of the adapters. Based on qPCR quantification, libraries were normalized to 2 nM.

Cluster Amplification and Sequencing

Cluster amplification of DNA libraries was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Illumina) using exclusion amplification chemistry and flowcells. Flowcells were sequenced utilizing sequencing-by-synthesis chemistry. The flowcells were then analyzed using RTA v.2.7.3 or later. Each pool of whole exome libraries was sequenced on paired 76 cycle runs with two 8 cycle index reads across the number of lanes needed to meet coverage for all libraries in the pool. Pooled libraries were run on HiSeq 4000 paired-end runs to achieve a minimum of 150x on target coverage per sample library. The raw Illumina sequence data were demultiplexed and converted to fastq files; adapter and low-quality sequences were trimmed. The raw reads were mapped to the hg38 human reference genome and the validated BAMs were used for downstream analysis and variant calling.

PCR-Free Whole Genome Sequencing

Preparation of Libraries for Cluster Amplification and Sequencing

An aliquot of genomic DNA (350 ng in 50 μL) was used as the input into DNA fragmentation (aka shearing). Shearing was performed acoustically using a Covaris focused-ultrasonicator, targeting 385bp fragments. Following fragmentation, additional size selection was performed using a SPRI cleanup. Library preparation was performed using a commercially available kit provided by KAPA Biosystems (KAPA Hyper Prep without amplification module) and with palindromic forked adapters with unique 8-base index sequences embedded within the adapter (purchased from IDT). Following sample preparation, libraries were quantified using quantitative PCR (kit purchased from KAPA Biosystems), with probes specific to the ends of the adapters. This assay was automated using Agilent’s Bravo liquid handling platform. Based on qPCR quantification, libraries were normalized to 1.7 nM and pooled into 24-plexes.

Cluster Amplification and Sequencing (HiSeq X)

Sample pools were combined with HiSeq X Cluster Amp Reagents EPX1, EPX2, and EPX3 into single wells on a strip tube using the Hamilton Starlet Liquid Handling system. Cluster amplification of the templates was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Illumina) with the Illumina cBot. Flowcells were sequenced to a minimum of 15x on HiSeq X utilizing sequencing-by-synthesis kits to produce 151bp paired-end reads. Output from Illumina software was processed by the Picard data processing pipeline to yield BAMs containing demultiplexed, aggregated, aligned reads. All sample information tracking was performed by automated LIMS messaging.

Illumina Infinium MethylationEPIC BeadChip Array

The MethylationEPIC array uses an 8-sample version of the Illumina Beadchip capturing > 850,000 DNA methylation sites per sample. 250 ng of DNA was used for the bisulfite conversion using Infinium MethylationEPIC BeadChip Kit. The EPIC array includes sample plating, bisulfite conversion, and methylation array processing. After scanning, the data were processed through an automated genotype calling pipeline. Data generated consisted of raw IDAT files and a sample sheet.

RNA Sequencing

Quality Assurance and Quality Control of RNA Analytes

All RNA analytes were assayed for RNA integrity, concentration, and fragment size. Samples for total RNA-seq were quantified on a TapeStation system (Agilent, Inc. Santa Clara, CA). Samples with RINs > 8.0 were considered high quality.

Total RNA-seq Library Construction

Total RNA-seq library construction was performed from the RNA samples using the TruSeq Stranded RNA Sample Preparation Kit and bar-coded with individual tags following the manufacturer’s instructions (Illumina, Inc. San Diego, CA). Libraries were prepared on an Agilent Bravo Automated Liquid Handling System. Quality control was performed at every step and the libraries were quantified using the TapeStation system.

Total RNA Sequencing

Indexed libraries were prepared and run on HiSeq 4000 paired-end 75 base pairs to generate a minimum of 120 million reads per sample library with a target of greater than 90% mapped reads. Typically, these were pools of four samples. The raw Illumina sequence data were demultiplexed and converted to FASTQ files, and adapter and low-quality sequences were quantified. Samples were then assessed for quality by mapping reads to the hg38 human genome reference, estimating the total number of reads that mapped, amount of RNA mapping to coding regions, amount of rRNA in the sample, number of genes expressed, and relative expression of housekeeping genes. Samples passing this QA/QC were then clustered with other expression data from similar and distinct tumor types to confirm expected expression patterns. Atypical samples were then SNP typed from the RNA data to confirm source analyte. FASTQ files of all reads were then uploaded to the GDC repository.

miRNA-seq Library Construction

miRNA-seq library construction was performed from the RNA samples using the NEXTflex Small RNA-Seq Kit (v3, PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) and bar-coded with individual tags following the manufacturer’s instructions. Libraries were prepared on the Sciclone Liquid Handling Workstation. Quality control was performed at every step, and the libraries were quantified using a TapeStation system and an Agilent Bioanalyzer using the Small RNA analysis kit. Pooled libraries were then size selected according to NEXTflex Kit specifications using a Pippin Prep system (Sage Science, Beverly, MA).

miRNA Sequencing

Indexed libraries were loaded on the Hiseq 4000 to generate a minimum of 10 million reads per library with a minimum of 90% reads mapped. The raw Illumina sequence data were demultiplexed and converted to FASTQ files for downstream analysis. Resultant data were analyzed using a variant of the small RNA quantification pipeline developed for TCGA (Chu et al., 2016). Samples were assessed for the number of miRNAs called, species diversity, and total abundance. Samples passing quality control were uploaded to the GDC repository.

Genomics and Transcriptomics Data Processing

Somatic Mutation Calling

Somatic variants were called by the Somaticwrapper pipeline, which includes four different callers, i.e., Strelka v.2 (Saunders et al., 2012), MUTECT v1.7 (Cibulskis et al., 2013), VarScan v.2.3.8 (Koboldt et al., 2012), and Pindel v.0.2.5 (Ye et al., 2009) from WES. We kept the exonic SNVs called by any 2 callers among MUTECT v1.7, VarScan v.2.3.8, and Strelka v.2 and indels called by any 2 callers among VarScan v.2.3.8, Strelka v.2, and Pindel v.0.2.5. For the merged SNVs and indels, we applied a 14X and 8X coverage cutoff for tumor and normal, separately. We also filtered SNVs and indels by a minimal variant allele frequency (VAF) of 0.05 in tumors and a maximal VAF of 0.02 in normal samples. Finally, we filtered any SNV which was within 10bp of an indel found in the same tumor sample.

Germline Variant Calling

Germline Variant Calling was performed using germlinewrapper v1.1, which implements multiple tools for the detection of germline INDELs and SNVs. Germline SNVs were identified using VarScan v2.3.8 (with parameters: --min-var-freq 0.10 --p-value 0.10, --min-coverage 3 --strand-filter 1) operating on a mpileup stream produced by samtools v1.2 (with parameters: -q 1 -Q 13) and GATK v4.0.0.0 (McKenna et al., 2010) using its haplotype caller in single-sample mode with duplicate and unmapped reads removed and retaining calls with a minimum quality threshold of 10. All resulting variants were limited to the coding region of the full-length transcripts obtained from Ensembl release 95 plus additional two base pairs flanking each exon to cover splice donor/acceptor sites. We required variants to have allelic depth ≥ 5 reads for the alternative allele. We filtered large INDELs that were longer than 100 bps.

DNA Methylation Array

The raw data from Illumina's EPIC methylation arrays were available as IDAT files from the CPTAC consortium. The methylation analysis was performed using the cross-package workflow methylationArrayAnalysis available on Bioconductor. In brief, the raw data IDAT files were processed to obtain the methylated (M) and unmethylated (U) signal intensities for each locus. The processing step included an unsupervised normalization step called functional normalization that has been previously implemented for Illumina 450K methylation arrays (Fortin et al., 2014). A detection p value was also calculated for each locus, and this p value captured the quality of detection at the locus with respect to negative control background probes included in the array. Loci having common SNPs (with MAF > 0.01), as per dbSNP build 132 through 147 via the UCSC “snp132common” track through “snp147common” track, were removed from further analysis. Beta values were calculated as M/(M+U), that is equal to the fraction methylated for each locus. Beta values of loci whose detection p values were > 0.01 were assigned NA in the output file. All loci were annotated with the EPIC Manifest from MethylationEPIC_v-1-0_B2.csv from the zip archive infinium-methylationepic-v1-0-b2-manifest-file-csv.zip from Illumina through the “IlluminaHumanMethylationEPICanno.ilm10b2.hg19” package on Bioconductor. To map EPIC arrays to the GRCh38 assembly, all probes were reannotated by annotation information from InfiniumAnnotation.

Copy-Number Analysis

Copy-number analysis was performed jointly leveraging both whole-genome sequencing (WGS) and whole-exome sequencing data of the tumor and germline DNA, using CNVEX (https://github.com/mctp/cnvex). CNVEX uses whole-genome aligned reads to estimate coverage within fixed genomic intervals, and whole-genome and whole-exome variant calls to compute B-allele frequencies at variable positions (we used TNScope germline calls). Coverages were computed in 10kb bins, and the resulting log coverage ratios between tumor and normal samples were adjusted for GC bias using weighted LOESS smoothing across mappable and non-blacklisted genomic intervals within the GC range 0.3-0.7, with a span of 0.5 (the target, blacklist, and configuration files are provided with CNVEX). The adjusted log coverage ratios (LR) and B-allele frequencies (BAF) were jointly segmented by a custom algorithm based on Circular Binary Segmentation (CBS). Alternative probabilistic algorithms were implemented in CNVEX, including algorithms based on recursive binary segmentation (RBS) (Gey and Lebarbier, 2008), and dynamic programming (Bellman, 1961), as implemented in the R package jointseg (Pierre-Jean et al., 2015). For the CBS-based algorithm, first LR and mirrored BAF were independently segmented using CBS (parameters alpha=0.01, trim=0.025) and all candidate breakpoints collected. The resulting segmentation track was iteratively “pruned” by merging segments that had similar LR, BAFs, and short lengths. For the RBS- and DP-based algorithms, joint-breakpoints were “pruned” using a statistical model selection method (Lebarbier, 2005). For the final set of CNV segments, we chose the CBS-based results as they did not require specifying a prior on the number of expected segments (K) per chromosome arm, were robust to unequal variances between the LR and BAF tracks, and provided empirically the best fit to the underlying data.

RNA Quantification and Circular RNA Prediction

The hg38 reference genome and RefSeq annotations were used for the RNA-seq data analysis and were downloaded from the UCSC table browser. First, CIRI (v2.0.6) was used to call circular RNA with default parameters and BWA (version 0.7.17-r1188) was used as the mapping tool. The cutoff of supporting reads for circRNAs was set to 10. Then we used a pseudo-linear transcript strategy to quantify gene and circular RNA expression (Li et al., 2017). In brief, for each sample, linear transcripts of circular RNAs were extracted and 75bp (read length) from the 3’ end was copied to the 5’ end. The modified transcripts were called pseudo-linear transcripts. Transcripts of linear genes were also extracted and mixed with pseudo-linear transcripts. RSEM (version 1.3.1) with Bowtie2 (version 2.3.3) as the mapping tool was used to quantify gene and circular RNA expression based on the mixed transcripts. After quantification, the upper quantile method was applied for normalization. The normalized matrix was log2-transformed and separated into gene and circular RNA expression matrices.

miRNA-Seq Data Analysis

Processed miRNA bam files were downloaded from GDC and transferred to fastq format using samtools (version 1.10). QuickMIRSeq (Zhao et al., 2017) with bowtie as a mapping tool (version 1.1.1) was used to quantify miRNA expression. The following parameters were used for QuickMIRSeq: 1) 2 bp extension / shorten were allowed in both upstream and downstream regions of mature miRNA; 2) The minimum and maximum length of miRNA reads were set to 16 and 28, respectively. Then RPM (reads per million) values were used to quantify miRNA expression levels.

HPV Virus Identification

The unmapped RNA-seq reads to the human reference genome were extracted and mapped to the virus reference by VirusScan (Cao et al., 2016). The reference contained the known HPV genotypes including the "high-risk" genotypes such as HPV 16 and HPV 18. Samples were classified as HPV positive using an empiric definition of detection of > 1,000 mapped RNA-seq reads.

Mutational Signature Analysis

Non-negative matrix factorization algorithm (NMF) was used in deciphering mutation signatures in cancer somatic mutations stratified by 96 base substitutions in trinucleotide sequence contexts. To obtain a reliable signature profile, we used the Somaticwrapper pipeline to call mutations from WES and WGS data. SignatureAnalyzer exploited the Bayesian variant of the NMF algorithm and enabled an inference for the optimal number of signatures from data itself at a balance between the data fidelity (likelihood) and the model complexity (regularization) (Kasar et al., 2015; Kim et al., 2016; Tan and Févotte, 2013). Signatures were compared against known signatures derived from COSMIC (Tate et al., 2019) and cosine similarity was calculated to identify the best match.

Gene Fusion Detection

Fusions in RNA-seq samples were called using three callers: STAR-Fusion v1.5.0 (Haas et al., 2019), EricScript v0.5.5 (Benelli et al., 2012), and INTEGRATE v0.2.6 (Zhang et al., 2016). As STAR-Fusion has higher sensitivity, calls made by this tool with higher supporting evidence (defined by fusion fragments per million total reads, or FFPM > 0.1) is required, or a given fusion must be reported by at least 2 callers being retained. Fusions present in the following databases were then excluded: 1) uncharacterized genes, immunoglobulin genes, mitochondrial genes, etc.; 2) fusions from the same gene or paralog genes; and 3) fusions reported in TCGA normal samples (Gao et al., 2018), GTEx tissues (reported in the STAR-Fusion output), and non-cancer cell studies (Babiceanu et al., 2016). Finally, normal fusions were filtered out from the tumor fusions.

Structural Variant Analysis

Structural variants in WGS samples were called with Manta 1.3.2 (Chen et al., 2016), retaining variants where sample site depth is less than 3x the median chromosome depth near one or both variant breakends, somatic score is greater than 30, and for small variants (<1000 bases) in the normal sample, the fraction of reads with MAPQ0 around either breakend does not exceed 0.4. It is optimized for the analysis of somatic variation in tumor/normal sample pairs. The paired and split-read evidence were combined during the SV discovery and scoring to improve accuracy. We prioritized the variants by the number of spanning read pairs which strongly (Q30) support the variants (>5 as high confidence level).

SCNA Arm and Focal Significance

From the segment-level SCNA data, we used GISTIC2 (Mermel et al., 2011) to assess the arm- and focal-level SCNA significance using the default parameters except for increased threshold of significance (i.e., -ta and -td parameters of GISTIC2) to 0.3 based on the distribution of germline copy number variants.

Proteomic and Phosphoproteomic Profiling Experiments

Sample Processing for Protein Extraction and Tryptic Digestion