INTRODUCTION

The Office of Professional Worklife (OPW) at Hennepin Healthcare System (HHS) has been measuring burnout and overseeing its prevention across approximately 700 providers (doctors and advanced practice providers, including nurse practitioners and physician assistants) for over 5 years. Current attention to disparities and discrimination in medicine motivated OPW to consider negative experiences due to gender and race as potential contributors to burnout.1, 2 The study objective was to use a new survey item to assess frequency of negative experiences and determine associations with burnout, teamwork, and values alignment.

METHODS

The validated ten-item Mini-Z quantifies satisfaction, burnout, and their workplace contributors including work control, chaotic workplaces, electronic medical record stress, teamwork, and values alignment.3, 4 The new, 5-point Likert scale item requests frequency of negative experiences due to gender and/or race, reading, “How often do you encounter negative experiences at work due to your gender and/or race? (e.g., being denied work opportunities, being isolated or treated as if you were not competent, experiencing repeated, small slights at work, or other forms of discrimination).” It was based on Pew Research’s comprehensive national 2017 STEM Survey on workplace experiences in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM).5 The item is unable to differentiate between negative experiences due to gender versus race.

In October 2018, we surveyed providers who were at or over 0.5FTE and had been working at HHS for 6 months or more. All 679 eligible providers received the survey via email and 461 (68%) responded. Reminder emails were sent out weekly for three weeks and providers were encouraged to participate by colleagues and department leaders. Participants answered demographic questions, including gender and race, along with the ten Mini-Z questions.

Since very few participants identified “other” as their gender versus “man” or “woman,” we only included those identifying as men or women. Survey data was aggregated, stratified by gender, and analyzed to determine the frequency of negative experiences due to gender and/or race. Logistic regression models assessed relationships between negative experiences, kept on a five-point scale, and binary outcomes of burnout, teamwork, and values alignment. Count and percentages of results for select demographic and relevant Mini-Z questions can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| N | 461 |

| Gender8 | |

| Female | 286 (63.1) |

| Male | 164 (36.2) |

| Other | 3 (0.7) |

| Race21 | |

| White | 370 (84.1) |

| Black/African American | 21 (4.8) |

| Latino(a) | 5 (1.1) |

| Asian | 21 (4.8) |

| Native American/Alaska Native | 2 (0.5) |

| Other | 21 (4.8) |

| Role | |

| Physician | 237 (51.4) |

| Nurse practitioner | 82 (17.8) |

| Physician assistant | 55 (11.9) |

| Nurse anesthetist | 22 (4.8) |

| Psychologist | 24 (5.2) |

| Other | 41 (8.9) |

| Discrimination frequency18 | |

| Frequently | 11 (2.5) |

| Fairly often | 32 (7.2) |

| Infrequent | 75 (16.9) |

| Rarely | 113 (25.5) |

| Never | 212 (47.9) |

| Burned-out12 | 183 (40.8) |

| Good values alignment18 | 350 (79.0) |

| High teamwork18 | 368 (83.1) |

| Satisfied with job12 | 361 (80.4) |

| High job-related stress12 | 251 (55.9) |

Superscripts represent the number missing for each question

Results

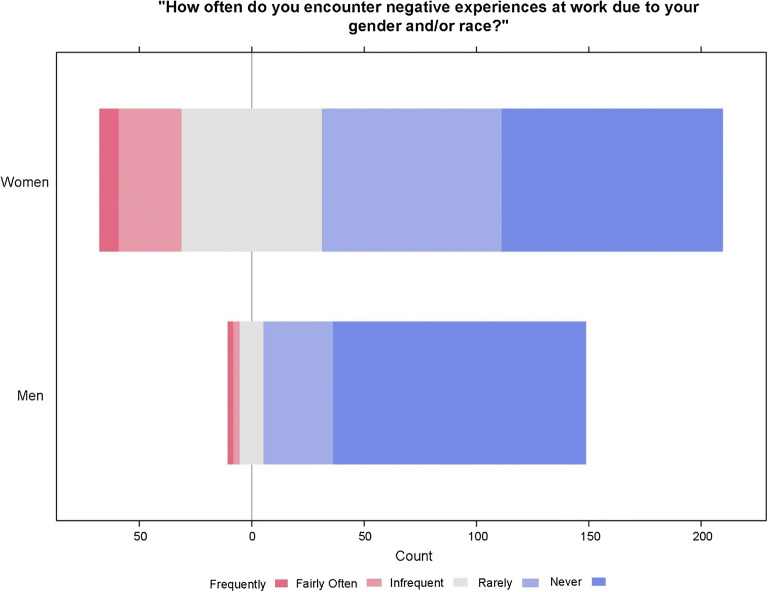

Over one in ten women (13%) reported negative experiences due to gender and/or race “fairly often” or “frequently” (the two highest choices for frequency), compared with 3.2% of men. Only 35% of women reported never encountering negative experiences due to gender nor race, compared with 70% of men (Cochran–Armitage test, p < 0.001) (Fig. 1). In regression analyses adjusted for gender, negative experiences due to gender and/or race were significantly associated with burnout, teamwork, and values alignment. Every one-unit Likert scale increase in frequency of negative experiences was associated with an 83% increase in odds of burnout (OR 1.83, p < 0.001, 95% CI [1.48, 2.26]), a 52% increase in odds of experiencing low teamwork (OR 1.52, p < 0.001, 95% CI [1.21, 1.92]), and a 93% increase in odds of experiencing low values alignment with leadership (OR 1.93, p < 0.001, 95% CI [1.54, 2.44]).

Figure 1.

Frequency of negative experiences due to gender in a sample of 461 clinicians at a safety-net hospital using a novel gender question. Women were significantly more likely to report negative experiences due to gender “frequently” or “fairly often,” at 13%, than men, at 3.2%. Only 35% of women reported never encountering negative experiences due to gender, compared with 70% of men (Cochran–Armitage test, p < 0.001).

DISCUSSION

In this preliminary investigation of a novel gender and race item and its relationship with burnout and organizational culture within a representative sample of providers at a safety-net hospital, women experience gender and/or race-related discrimination more frequently than men, and it is linked to burnout, experiences of poor teamwork, and poor values alignment with leadership. This demonstrates that negative gender and/or race-related experiences may be a predictor or component of burnout in women providers and highlights gender disparities in wellness. A limitation is that the item cannot differentiate between negative experiences due to gender versus race. Additionally, selection bias may have resulted in burned-out providers being more likely to participate in the survey. Future studies will track negative experiences due to gender and race separately, and will investigate impact of gender equity interventions.

CONCLUSION

Negative experiences due to gender and/or race significantly correspond with burnout, teamwork, and values alignment. Like burnout, negative experiences due to gender are potentially a systemic issue. These experiences may comprise appropriate targets for institutional change, such as implicit bias training, pursuing pay equity, improving family and medical leave, and career development training.2

Funding Information

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, grant UL1TR002494.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest. In the interest of full disclosure, Dr. Linzer is supported through Hennepin Healthcare for training and research in physician burnout prevention by the American Medical Association(AMA), American College of Physicians (ACP), American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) Foundation, and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI). Ms. Poplau is supported through Hennepin Healthcare Research Institute for her work in burnout prevention research and training in burnout reduction by the AMA and ACP. Dr. Goelz is supported through Hennepin Healthcare for training and research in physician burnout prevention by the AMA and the IHI. Ms. Audi is supported through Hennepin Healthcare Research Institute for her work in burnout prevention research and training in burnout reduction by the AMA, IHI, and ABIM.

Disclaimer

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Jagsi R, Griffith KA, Jones R, Perumalswami CR, Ubel P, Stewart A. Sexual harassment and discrimination experiences of academic medical faculty. JAMA. 2016;315:19. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.2188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Butkus R, Serchen J, Moyer DV, Bornstein SS, Hingle ST. Achieving gender equity in physician compensation and career advancement: a position paper of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(10):721–723. doi: 10.7326/M17-3438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olson K, Sinsky C, Rinne ST, et al. Cross-sectional survey of workplace stressors associated with physician burnout measured by the Mini-Z and the Maslach Burnout Inventory. Stress Health. 2019;35(2):157–175. doi: 10.1002/smi.2849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Linzer M, Poplau S, Babbott S, et al. Worklife and wellness in academic general internal medicine: results from a national survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(9):1004–1010. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3720-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Funk C, Parker K. Women and men in STEM often at odds over workplace equity. Pew Research Center (2018).