Abstract

Since 2007, inpatient antibiotic stewardship programs have been required for all Joint Commission–accredited hospitals in the USA. Given the frequency of ambulatory antibiotic prescribing, in June 2019, the Joint Commission released new standards for antibiotic stewardship programs in ambulatory healthcare. This report identified five elements of performance (EPs): (1) Identify an antimicrobial stewardship leader, (2) establish an annual antimicrobial stewardship goal, (3) implement evidence-based practice guidelines related to the antimicrobial stewardship goal, (4) provide clinical staff with educational resources related to the antimicrobial stewardship goal, and (5) collect, analyze, and report data related to the antimicrobial stewardship goal. We provide eight practical tips for implementing the EPs for antimicrobial stewardship: (1) Identify a collaborative leadership team, (2) partner with informatics, (3) identify national prescribing patterns, (4) perform a needs assessment based on local prescribing patterns, (5) review guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of the selected condition, (6) identify systems-level interventions to help support providers in making appropriate treatment decisions, (7) prioritize individual EPs for your institution, and (8) re-assess local data to identify areas of strength and deficiency in local practice.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11606-020-06365-1.

BACKGROUND

In 2007, the Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) developed the first guidelines for antibiotic stewardship programs (ASPs),1 and these programs are now required at all US hospitals.2 In 2019, the Joint Commission further expanded the requirements for ASPs to designated ambulatory care facilities. Although data regarding the prevalence of ambulatory ASPs are scarce, by July 2018, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ Quality Innovation Networks-Quality Improvement Organizations had already supported over 7500 ambulatory care facilities in the implementation of ASPs.3 Multiple studies document that ASPs can help reduce inappropriate prescribing in their respective study populations.4–7 For example, Gerber et al. documented that a program of education, auditing, and feedback resulted in improvement in antibiotic prescribing patterns in acute bacterial respiratory infections in children.4 While the long-term benefits of ASPs are not yet known, rising rates of antibiotic resistance and adverse drug events demand robust, longitudinal efforts in ambulatory antibiotic stewardship.8–12

Overuse of antibiotics and inappropriate antibiotic selection have contributed to rising rates of resistance.8–12 There is also growing evidence that prolonged antibiotic duration increases the risk of adverse events.12 Thus, it is critical to focus efforts on utilizing the lowest dose and narrowest spectrum antibiotic to decrease the rate of resistance development and drug-related adverse effects. Primary care providers (PCPs) are frequent prescribers of antibiotics for a variety of ambulatory infections, supporting the need for programs that specifically target improving PCP prescribing practices.

MODEL FOR DESIGNING ANTIBIOTIC STEWARDSHIP PROGRAMS

To address these concerns, the 2019 Joint Commission report requires antibiotic stewardship programs for accredited outpatient practices. The new elements of performance (EP)13 are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

R3 Report Elements of Performance

| 1 | Identify an antimicrobial stewardship leader |

| 2 | Establish an annual antimicrobial stewardship goal |

| 3 | Implement evidence-based practice guidelines related to the antimicrobial stewardship goal |

| 4 | Provide clinical staff with educational resources related to the antimicrobial stewardship goal |

| 5 | Collect, analyze, and report data related to the antimicrobial stewardship goal |

While the Joint Commission has suggested resources, such as the Quality Improvement Organizations’ Field Guide to Antibiotic Stewardship in Outpatient Settings,3 to help organizations with the initiation of ambulatory antimicrobial stewardship programs (AAMPs), the implementation of such comprehensive action plans may seem daunting.

Due to our firm commitment to antimicrobial stewardship and in preparation for the anticipated Joint Commission requirements, we developed an initial ambulatory antimicrobial stewardship initiative in 2018. We present a model for the initiation of an AAMP utilizing the stepwise approach presented in the R3 Report2 in a university internal medicine residency clinic. We have also included the key lessons learned throughout this pilot for future ambulatory antimicrobial stewardship projects (Table 2). This model may be utilized in both academic and non-academic practices to guide the initiation of AAMPs.

Table 2.

Tips for Successful Execution of an ASP

| 1 | Think of the antimicrobial stewardship leader as a leadership team as opposed to one individual. Develop an inter-professional team to collaborate and develop a systems-based approach. |

| 2 | Partner with informatics to use electronic medical record data to identify regionally prevalent infections. |

| 3 | If available, review national prescribing patterns for comparison. |

| 4 | Perform a needs assessment to identify deficiencies in local prescribing patterns. |

| 5 | Review evidence for diagnosis and treatment of the selected condition. Develop local practice guidelines that incorporate current literature and any unique local factors, such as community resistance patterns, that may affect appropriate management in your clinical setting. |

| 6 | Identify systems-level interventions that support providers in making appropriate treatment decisions. Consider the use of the entire inter-professional care team. |

| 7 | Perform the EPs non-sequentially and in conjunction with one another as appropriate for your setting and resources. |

| 8 | Utilize national data and trends to help inform your initial directions, but perform a local needs assessment and target interventions to practice-specific deficiencies. |

EPs elements of performance

EP 1: Identify an Antimicrobial Stewardship Leader

Although identification of an antibiotic stewardship leader is an important initial step, it may seem formidable for a single individual to coordinate an AAMP. Further, a multidisciplinary approach has the highest likelihood of success in both academic and non-academic practices.14 We adopted a team approach to leadership of our AAMP. Our team included a senior internal medicine faculty member with experience in population health and infection prevention (antimicrobial stewardship leader); junior faculty members and trainees, who co-designed and implemented the intervention; and information technology (IT) specialists, who assisted with data extraction from the electronic medical record. We collaborated with clinical leadership including nursing, pharmacy, and office staff to ensure a systems-based approach to intervention planning. Our team developed the antimicrobial stewardship goal (EP2), evidence-based guidelines on acute bacterial rhinosinusitis (ABRS) diagnosis and treatment (EP3), provided resident and staff education (EP4), and analyzed data to track outcomes (EP5). This multidisciplinary approach led to rapid implementation of our program and ongoing quality improvement initiatives. Maintaining a motivated and skilled inter-disciplinary team helps ensure the long-term success of the AAMP.

Tip 1: Think of the antimicrobial stewardship leader as a leadership team as opposed to one individual. Develop an inter-professional team to collaborate and develop a systems-based approach.

EP 2: Establish an Annual Antimicrobial Stewardship Goal

Acute upper respiratory infections ranked seventh in the leading primary diagnosis groups for office visits in 2014,15 and the rate of inappropriate antibiotic prescribing for ABRS is high.16 Based on the frequency of annual upper respiratory tract infection visits and national data suggestive of high rates of inappropriate prescribing, we chose the appropriate diagnosis and management of ABRS as our initial antimicrobial stewardship goal. We then identified national trends in antibiotic prescribing patterns for ABRS. We developed the following goals:

To identify the local rate of inappropriate antibiotic prescribing in ABRS defined by appropriate diagnosis, antibiotic selection, and antibiotic dose and duration.

- To decrease the rate of inappropriate antibiotic prescribing, defined as inappropriate antibiotic selection, or inappropriate dose or duration of an appropriate antibiotic, to 20%, half the rate of inappropriate prescribing identified in a prior study.16 We aimed to accomplish this goal by:

- Educating providers on evidence-based management of ABRS

- Developing a decision-support tool for real-time use with patients

- Creating a personal performance data reporting system

We suggest that developing a close partnership with institutional IT teams is key to understanding what data can be extracted from the electronic medical record. This data will assist with the identification of common local infectious pathologies. Next steps may include a literature search to investigate national antibiotic prescribing patterns for these conditions, such as those presented by the Centers for Disease Control.17 Identifying areas of deficiency that are prevalent elsewhere may help determine the highest yield diagnoses.

To further inform our decision to proceed with targeting the diagnosis of ABRS, we sought to confirm that local prescribing patterns aligned with national data. We performed a retrospective pilot chart review to define the rate of inappropriate prescribing in our academic primary care practice.

Tip 2: Partner with informatics to use the electronic medical record to identify regionally prevalent infections.

Tip 3: If available, review national prescribing patterns for comparison.

Tip 4: Perform a needs assessment to identify deficiencies in local prescribing patterns.

EP 3: Implement Evidence-Based Practice Guidelines Related to the Antimicrobial Stewardship Goal

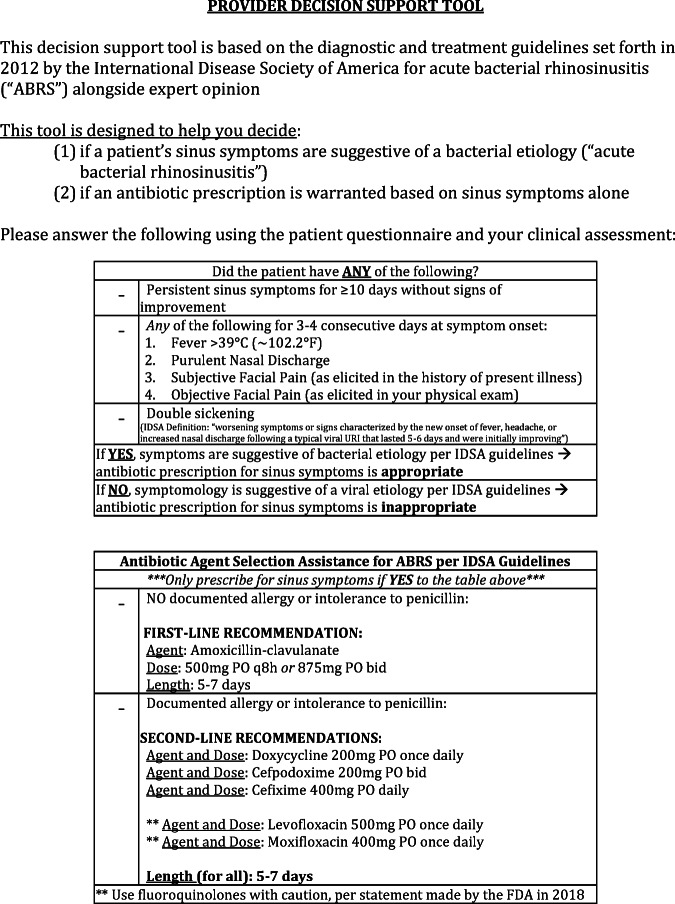

Once we selected a target diagnosis, we performed a comprehensive literature review to determine best practices in the management of ABRS. We based our assessment and intervention on the IDSA’s 2012 guidelines for distinguishing between ABRS and viral sinusitis.18 Additionally, we reviewed the IDSA treatment guidelines for first- and second-line antibiotics. We were initially challenged by the relative vagueness of the distinguishing symptoms, such as facial pain as a sign of severe symptoms. We found it to be critical for the stewardship team to be consistent regarding the interpretation of the selected guidelines. Due to the age of the IDSA guidelines, we reviewed additional sources to develop an evidence-based, up-to-date approach to diagnosis and management of ABRS. For example, we modified the IDSA guideline suggestion for the use of fluoroquinolones in penicillin-allergic patients. We chose to prioritize the use of other second-line agents over fluoroquinolones, given the updated data on the relative risks of fluoroquinolones.19 Based on this literature review, we developed an algorithm (Fig. 1) for the appropriate identification and diagnosis of ABRS. This algorithm was used as a chart review tool to complete our pilot chart reviews.

Tip 5: Review evidence for diagnosis and treatment of the selected condition. Develop local practice guidelines that incorporate current literature and any unique local factors, such as community resistance patterns that may affect appropriate management in your clinical setting.

Figure 1.

Chart review tool for determination of appropriateness of antibiotic prescribing. Algorithm used to determine the appropriateness of antibiotic prescribing for presumed cases of acute bacterial rhinosinusitis (ABRS) at an Internal Medicine Residents Clinic in Hershey, PA, from 2015 to 2018. The diagnostic criteria used to evaluate these cases were obtained from the Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA), as were the recommended first- and second-line agents (with notable regard to any documented history of penicillin allergy) and their associated dosages and durations.18 Prescriptions were only deemed appropriate if they correctly met all of the following elements: (a) they were associated with a visit in which the provider correctly identified a case of ABRS (as evaluated via a retrospective review using the aforementioned diagnostic criteria), (b) a correct agent was selected based on the presence or lack of a documented penicillin allergy, (c and d) the prescribed dose and duration were correct based on the IDSA guidelines.18

EP 4: Provide Clinical Staff with Educational Resources Related to the Antimicrobial Stewardship Goal

We adopted a multimodal approach to improving antibiotic prescribing for ABRS. Per the recommendations of the Field Guide to Antibiotic Stewardship, we posted signage3 throughout the clinic to educate patients on the dangers of inappropriate antibiotic prescribing and to help facilitate discussions between patients and providers regarding the decision not to prescribe antibiotics. We developed an educational intervention that reviewed the evidence-based criteria for diagnosis, data on current prescribing patterns in our practice, and evidence-based treatment guidelines of ABRS. This short, interactive didactic session was delivered during mandatory meetings for our resident providers from August 29 to October 10, 2019, in preparation for the coming cold and flu season. Lastly, we developed a symptom report survey (Appendix 1) to be given to all patients presenting with upper respiratory infection symptoms in our resident clinic starting on December 2, 2019. The patient symptom survey allows patients to rapidly communicate associated symptoms with providers. It was accompanied by a decision support algorithm (Appendix 2) that aided providers in correctly diagnosing ABRS and selecting the proper antibiotic, dose, and duration, accounting for patients’ medication allergies.

Tip 6: Identify systems-level interventions that support providers in making appropriate treatment decisions. Consider the use of the entire inter-professional care team.

EP 5: Collect, Analyze, and Report Data Related to the Antimicrobial Stewardship Goal

Using the chart review tool described above, we performed an initial chart review of approximately 200 charts to identify baseline data on local prescribing patterns to inform our interventions. With the help of our informatics team, we identified all visits from October 1, 2015, to December 31, 2018, during which an ICD-10 code associated with ABRS was utilized, and an antibiotic was prescribed. Exclusion criteria included comorbid diagnoses that may have lowered the threshold for treatment with antibiotics, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases. A team of three reviewers comprised of two faculty members (ND, EH), and one trainee (RK) utilized the chart review tool to review office notes to determine the appropriateness of treatment. Our pre-intervention rates of diagnostic accuracy were much higher than expected (97% of cases). However, we found that the treatment strategy was evidence-based in only 40% of cases. Inappropriate prescribing was due to incorrect antibiotic selection in 64% of cases, incorrect duration in 27% of cases, and incorrect dose in 8% of cases. Baseline data allowed us to target our intervention to these prescribing practices.

Our initial data reporting required a time-intensive chart review. Our pilot review revealed that prescribers were accurately diagnosing ABRS. Our IT team designed an electronic system to identify ABRS cases using our inclusion and exclusion criteria, and to provide data on the selection of antibiotic, dose, and duration. Given the high rate of accurate diagnosis, we determined that further manual chart review to assess the appropriateness of diagnosis would be unnecessary. We plan to rely on the electronic medical record output from our IT team for the appropriateness of treatment. Additionally, while our initial decision support tool was piloted as a paper form, we will work with our informatics team to embed the tool into our electronic medical record to provide real-time feedback on the appropriateness of proposed prescriptions. We will provide individual and practice-level data on ABRS practice patterns at regular intervals, as providing such feedback has been shown to improve quality measures in ambulatory settings.20

Tip 7: Perform the EPs non-sequentially and in conjunction with one another as appropriate for your settings and resources.

Tip 8: Utilize national data and trends to help inform your initial directions, but perform a local needs assessment and target interventions to practice-specific deficiencies.

In addition to collecting post-intervention data in our own practice, next steps for this work include expanding our data collection and intervention implementation to all primary care clinics within our institution. We will then utilize a similar method to approach other infectious conditions commonly treated in the ambulatory setting, such as urinary tract infections.

CONCLUSION

Ultimately, we have found this Joint Commission requirement to be timely and crucial to improving the ambulatory care of patients. This practical, stepwise approach is widely applicable as (1) the leadership team roles may be filled by varied clinicians and staff depending on availability and interest, and (2) the targeted infection and subsequent intervention are designed to address common local conditions and identified practice pattern deficiencies. These tips complement the EPs and may be useful in satisfying the Joint Commission requirements and providing evidence-based care to patients with increasingly complex medical conditions.

Supplementary Information

(DOCX 29 kb)

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Thomas Abendroth, Dr. Michael Katzman, and Dr. Jennifer Kraschnewski for their contributions.

Appendix 1. Patient symptom report survey

Appendix 2. Provider decision support tool

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Ethical Approval

This study was deemed “not human research” by the Institutional Review Board. IRB exemption number: STUDY00010282

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Dellit TH, Owens RC, McGowan JE, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America guidelines for developing an institutional program to enhance antimicrobial stewardship. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(2):159–177. doi: 10.1086/510393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Joint Commision. R3 Report: new antimicrobial stewardship standard. 2016. Issue 8. Available https://www.jointcommission.org/en/standards/r3-report/r3-report-issue-8-new-antimicrobial-stewardship-standard/ Accessed December 23, 2019.

- 3.A Field Guide to Antibiotic Stewardship in Outpatient Settings. Quality Improvement Organizations. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 2018. https://qioprogram.org/sites/default/files/editors/141/C310_Field_Guide_20180730_FNL.pdf. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- 4.Gerber JS, Prasad PA, Fiks AG, et al. Effect of an Outpatient Antimicrobial Stewardship Intervention on Broad-Spectrum Antibiotic Prescribing by Primary Care Pediatricians: A Randomized Trial. JAMA. 2013;309(22):2345–2352. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.6287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meeker D, Linder JA, Fox CR, et al. Effect of Behavioral Interventions on Inappropriate Antibiotic Prescribing Among Primary Care Practices: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2016;315(6):562–570. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finkelstein JA, Huang SS, Kleinman K, et al. Impact of a 16-Community Trial to Promote Judicious Antibiotic Use in Massachusetts. Pediatrics. 2008;121(1):e15–e23. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Little P, Stuart B, Francis N, et al. Effects of internet-based training on antibiotic prescribing rates for acute respiratory-tract infections: a multinational, cluster, randomised, factorial, controlled trial. Lancet. 2013;382(9899):1175–1182. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60994-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klepser ME, Dobson EL, Pogue JM, et al. A call to action for outpatient antibiotic stewardship. JAPhA. 2017;57(4):457–463. doi: 10.1016/j.japh.2017.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goossens H, Ferech M, Vander Stichele R, Elseviers M. Outpatient antibiotic use in Europe and association with resistance: a cross-national database study. Lancet. 2005;365(9459):579–587. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)70799-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shehab N, Patel PR, Srinivasan A, Budnitz DS. Emergency Department Visits for Antibiotic-Associated Adverse Events. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(6):735–743. doi: 10.1086/591126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chitnis AS, Holzbauer SM, Belflower RM, et al. Epidemiology of community-associated clostridium difficile infection, 2009 through 2011. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(14):1359–1367. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.7056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vaughn VM, Flanders SA, Snyder A, et al. Excess antibiotic treatment duration and adverse events in patients hospitalized with pneumonia: a multihospital cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171(3):153–163. doi: 10.7326/M18-3640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The Joint Commision. R3 Report: antimicrobial stewardship in ambulatory health care. 2019. Issue 23. Available at: https://www.jointcommission.org/en/standards/r3-report/r3-report-issue-23-antimicrobial-stewardship-in-ambulatory-health-care/. Accessed December 21, 2019.

- 14.Cunha CB. Antimicrobial stewardship programs: principles and practice. Med Clin. 2018;102(5):797–803. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2018.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2014 State and National Summary Tables. 2014. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/namcs_summary/2014_namcs_web_tables.pdf. Accessed March 4, 2018.

- 16.Fleming-Dutra KE, Hersh AL, Shapiro DJ, et al. Prevalence of inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions among us ambulatory care visits, 2010-2011. JAMA. 2016;315(17):1864–1873. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.4151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.What Do We Know About Antibiotic Use in Outpatient Settings? Antibiotic Prescribing and Use. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2019. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/antibiotic-use/stewardship-report/outpatient.html. Accessed April 24, 2020.

- 18.Chow A, Benninger M, Brook I, et al. IDSA Clinical Practice Guideline for Acute Bacterial Rhinosinusitis in Children and Adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(8):e72–e112. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA warns about increased risk of ruptures or tears in the aorta blood vessel with fluoroquinolone antibiotics in certain patients. 2018. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-warns-about-increased-risk-ruptures-or-tears-aorta-blood-vessel-fluoroquinolone-antibiotics. Accessed January 3, 2020.

- 20.Makary MA, Mehta A, Xu T. Improving wisely using physician metrics. AJMQ. 2018;33(1):103–105. doi: 10.1177/1062860617704504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 29 kb)