Abstract

Insight into predictors of cardiac involvement in inflammatory myopathies is sparse. A negative prognostic role of anti-mitochondrial antibodies (AMA) has been noticed and is supported by the current case. We describe a male patient who at the age 40 suffered a cardiac arrest and over the following months experienced progressive heart failure, arrhythmias and proximal muscle weakness. Clinical, genetic and serologic testing and repeated imaging- and histopathological investigations resulted in a diagnosis of AMA-associated, necrotizing, inflammatory myositis with cardiac involvement. Besides a cardiac resynchronization therapy defibrillator, heart failure and antiarrhythmic drugs the patient received successive immunosuppressants, which improved skeletal muscle strength but not cardiac disease progression. At age 45 he died from end-stage heart failure. Clinicians must be aware of AMA-associated myositis as a cause of unclarified heart disease, even in patients with initially sparse extra-cardiac manifestations. Further knowledge of treatment strategies is highly needed for this disease entity.

INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory myopathy is a heterogeneous disease entity affecting primarily the skeletal muscles. Anti-mitochondrial antibodies (AMA)—the serological hallmark of primary biliary cholangitis (PBC)—exist in a subgroup of myositis patients and may predict serious cardiac involvement [1, 2]. Awareness of AMA and their pathophysiological role in myositis is of great therapeutic and prognostic relevance as illustrated by this case.

CASE REPORT

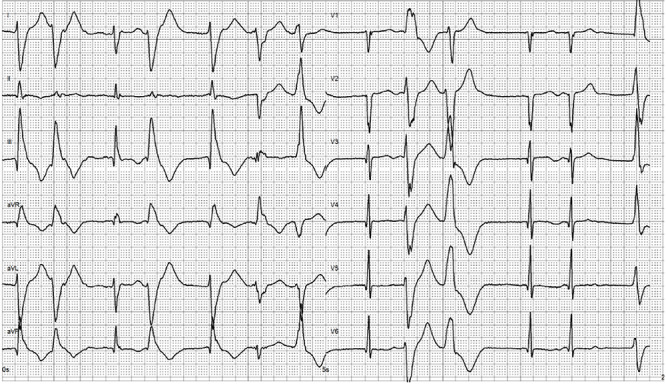

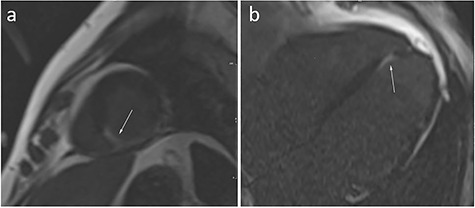

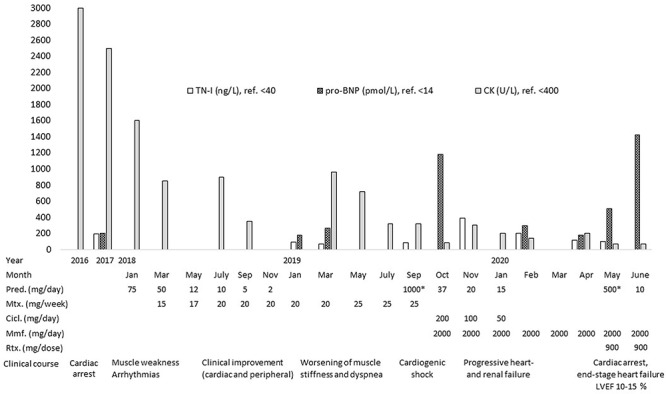

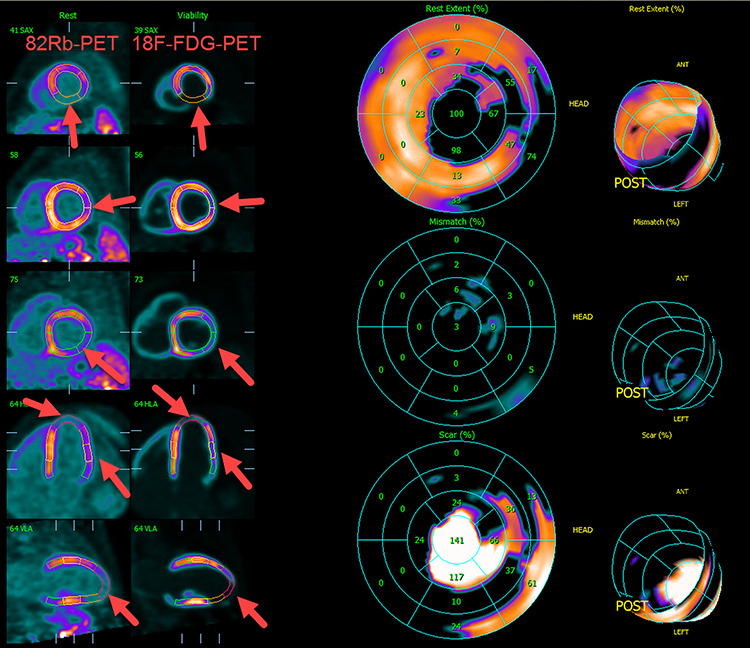

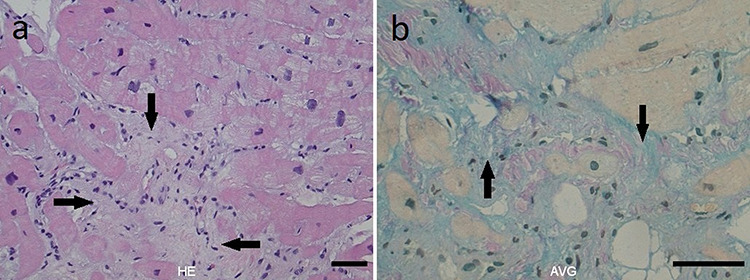

A 40-year-old male with a medical history of Graves’ disease and paroxysmal atrial flutter (PAF) was admitted to the hospital on February 2016 after resuscitation for cardiac arrest/ventricular fibrillation (VF). He had no risk factors for ischemic heart disease. At arrival to the hospital, the electrocardiogram showed atrial fibrillation, ventricular extra systoles and q-waves in anterior leads (Fig. 1). In hospital heart monitoring showed paroxysmal complete heart block. Blood tests revealed elevated troponin-T (262, [<14 ng/L]), creatine kinase (CK) myocardial band (46,1 [<7 μg/L]) and total CK (2530 [25–400 U/l]). Chest X-ray showed cardiomegaly, and transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) disclosed dilatation of left ventricle with ejection fractions (LVEF) of 25–30%, hypofunction of right ventricle and inferoseptal akinesia. Coronary angiography (CAG) showed normal coronary arteries. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMRI) confirmed inferoseptal akinesia of the distal part of the myocardium in the left ventricle where late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) was found in a subendocardial, almost transmural pattern (Fig. 2a and b). A Cardiac-Resynchronization-Therapy-Defibrillator device (CRT-D) was implanted, and anticoagulants, antiarrhythmics, statin and heart failure therapy were started. The patient complained of muscle weakness for 2 years. Medical records showed elevated total CK (2000–3000 U/l) tracing back to 2014. Muscle strength testing confirmed proximal weakness of all extremities but no other signs of rheumatic/neurologic disease. The patient was subsequently followed by both cardiologists and neurologists, where progressive muscular weakness, repetitive supraventricular and ventricular arrhythmias and elevated cardiac/muscle enzymes were registered between 2016 and 2017 (Fig. 3). Serological tests for myositis-specific autoantibodies (MSAs) including anti-HMGCR, ANA and genetics for neuromuscular diseases were negative. Whole-body positron-emission-tomography computed-tomography (PET-CT) and pulmonary function tests were normal. Muscle biopsy showed fiber variability and cell necrosis compatible with immune-mediated, necrotizing myopathy. Prednisolone (75 mg/day) was initiated in January 2018 resulting in improved physical performance. In March 2018 methotrexate (MTX) (15–25 mg/week) was added and prednisolone tapered, resulting in continued clinical improvement and stable LVEF of 35%. In March 2019, while treated with MTX (20 mg/week) monotherapy, the patient experienced worsening of muscle weakness and dyspnea. Blood tests showed rising total CK (Fig. 3) and X-ray revealed pulmonary congestion. The condition improved transitorily on diuretics and increased MTX (25 mg/week). Six months later, the patient was brought to intensive care in cardiogenic shock due to decompensated severe biventricular failure. He was stabilized by inotropic support, diuretics, amiodarone, upregulation of CRT pace and glucocorticoids. TTE depicted biventricular hypofunction/dilatation (LVEF 10–15%), and a cardiac PET-CT (F-18-FDG/Rb-82) showed nonviable perfusion defect in the apex and lateral wall of the left ventricle (Fig. 4). A myocardial biopsy revealed mild to moderate hypertrophy and maturing replacement fibrosis with alcian-positive matrix indicating the presence of glycosaminoglycans as seen in early regeneration. Furthermore, endothelial proliferation and a few inflammatory cells were seen in the biopsy, suggesting a recent loss of myocytes (Fig. 5a and b). Cyclosporine (200 mg/day) and mycophenolate mofetil (2 g/day) were added to prednisolone (15 mg/day) to attenuate any inflammatory component. Despite stable peripheral muscle function, no convincing cardiac effect appeared. The combination of heart disease and myositis led to test for AMA in April 2020. AMA were present in unmeasurable high titers (>220 [<4 kIU/L]), supporting a diagnosis of cardiomyopathy related to AMA-associated inflammatory myositis (AMA-IM). In May 2020 rituximab therapy was started but unfortunately no cardiac improvement was achieved. Due to severe chronic renal impairment and ultimately liver failure the patient was not a candidate for heart transplantation. He died in cardiogenic and septic shock in July 2020.

Figure 1.

Electrocardiogram after resuscitation for cardiac arrest showing atrial fibrillation, ventricular extra systoles and q-waves along the anterior leads.

Figure 2.

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMRI). Late gadolinium enhancement images in the short axis (a), and four chamber (b) of the heart. The arrows point to the pathologic area of the myocardium (white area in the background of normal, black, myocardium).

Figure 3.

Serological disease activity markers including levels of Troponin-I (TN-I), pro B-type Natriuretic Peptide (pro-BNP) and total Creatine Kinase (CK) over time and in relation to the clinical course and treatment with Prednisolone (Pred.)/*methylprednisolone, Methotrexate (MTX), Ciclosporin (Cicl.), Mycophenolate mofetil (Mmf) and Rituximab (Rtx).

Figure 4.

Cardiac PET-CT with F-18-FDG/Rb-82 revealing nonviable perfusion defect in the apex and the lateral wall of the left ventricle (arrows).

Figure 5.

Histopathological images of myocardial biopsy showing (a, HE) mild to moderate hypertrophy and replacement fibrosis (arrow) with endothelial proliferation, few inflammatory cells and (b, AVG) alcian-positivity (arrow).

DISCUSSION

AMA-IM is a rare and sparsely described disease entity occurring independently or along with other autoimmune conditions, especially PBC [1–3]. Two previous case series found AMA in 0.006 and 11.3%, respectively, of patients with inflammatory myopathy—a variation probably reflecting the limited amount of data in a rare entity [1, 2]. Cardiac involvement of AMA-IM is a rather new recognition only described by a few, previous case reports/series within the last decades [1–5].

Little is known about the clinical and histopathological phenotype of AMA-IM. In consistency with our observations, previous cases report polymorph cardiac involvement including arrhythmias, cardiomyopathy and heart failure as prominent clinical features [1–6], and muscle biopsies with varying degrees of inflammation, atrophy and fibrosis [1, 3–5].

Our patient developed PAF at age 35, which was perceived as a complication to Graves thyrotoxicosis. Retrospectively, PAF could have been an initial symptom of AMA-IM, as it continued despite normalization of thyroid function, and was succeeded by severe conduction abnormalities, rising total CK and decreasing muscle strength over the following years. Previous reports confirm that cardiac manifestations often precede muscle symptoms in AMA-IM, increasing the risk of misdiagnosing [1, 2]. In our case, the diagnostic process was further challenged by ambiguous test results as MSAs and ANA screening appeared normal, and neither imaging nor biopsies showed active inflammation. The muscle biopsy showed a necrotizing myopathy, which was not associated to statin as Atorvastatin was prescribed years after the onset of muscle involvement and no anti-HMGCR antibodies were detected. In the endomyocardial biopsy, myocarditis was not directly observed. However, the focal loss of myocytes and replacement with alcian positive material as part of the regenerative process suggests a recent damaging event, which may be myocarditis. The CMRI findings of LGE following cardiac arrest could be due to coronary thromboembolism or an inflammatory process of the myocardium. The former seems unlikely given the normal coronary arteries on the previous CAG. Hence, the initially sparse muscle symptoms and prolonged diagnostic process with step-wise exclusion of genetic -, other rheumatic-, ischemic- and malignant diseases, before AMA testing provided a final diagnosis, caused a treatment delay, which might in part explain the insufficient cardiac responsiveness to immune suppressants in our patient. However, a diminished cardiac versus muscular response to immunosuppressants in AMA-IM has been observed in previous cases, across genders, disease durations and drug types [1, 2, 4, 5]. Taken together, this might point to a need for more aggressive strategies to reverse the cardiac manifestations.

In conclusion, our case supports that cardiac involvement can be a severe complication in AMA-IM and emphasizes the importance of testing for AMA in etiologically unclarified inflammatory myopathies and cardiac failure. The lack of treatment effect on cardiac failure in our and previous cases may indicate that very early and aggressive management of heart involvement is necessary. However, future systematic studies are needed to clarify the optimal treatment strategies for this disease entity.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

P.H., N.W., K.R., R.P., P.H.A., T.H.LJ. and L.D. declare no conflicts of interest.

FUNDING

There was no funding for this case report.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

No approval from the Ethics Committee is required for this study according to Danish Legislation.

CONSENT

A written consent form has been fulfilled by the patient.

GUARANTOR

Louise Pyndt Diederichsen, MD, PhD.

REFERENCES

- 1. Maeda MH, Tsuji S, Shimizu J. Inflammatory myopathies associated with anti-mitochondrial antibodies. Brain 2012;135:1767–77. doi: https://academic.oup.com/brain/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/brain/aws106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Albayda J, Khan A, Casciola-Rosen L, Corse AM, Paik JJ, Christopher-Stine L. Inflammatory myopathy associated with anti-mitochondrial antibodies: a distinct phenotype with cardiac involvement. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2018;47:552–6. doi: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0049017217302391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Varga J, Heiman-Patterson T, Muñoz S, Love LA. Myopathy with mitochondrial alterations in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis and antimitochondrial antibodies. Arthritis Rheum 1993;36:1468–75. 10.1002/art.1780361020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bujo S, Amiya E, Kojima T, Yamada S, Maki H, Ishizuka M, et al. Variable cardiac responses to immunosuppressive therapy in anti-mitochondrial antibody-positive myositis. Can J Cardiol 2019;35:1604.e9–1604.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2019.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yamanaka T, Fukatsu T, Ichinohe Y, Hirata Y. Antimitochondrial antibodies-positive myositis accompanied by cardiac involvement. BMJ Case Rep 2017;bcr2016218469. doi: http://casereports.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/bcr-2016-218469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Koyama M, Yano T, Kikuchi K, Nagahara D, Ishibashi-Ueda H, Miura T. Lethal heart failure with anti-mitochondrial antibody: an arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J 2016;ehw403. doi: https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/eurheartj/ehw403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]