Abstract

Background

Combining radiotherapy (RT) with programmed death 1 (PD-1)/programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitors has been shown to enhance anti-tumor effects in the treatment of non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC). Pulmonary toxicity is a major adverse effect of thoracic RT in NSCLC patients, whether it is administered alone or in combination with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors. This study aimed to evaluate the potential pulmonary toxicity of RT combined with concurrent PD-1 inhibitor and to clarify the underlying mechanisms.

Methods

Radiation-induced lung injury (RILI) was induced in C57BL/6 mice by given 24 Gy in three fractions on consecutive days, with or without concurrent injection of anti-PD-1 antibody. On days 3, 7, 14, and 28 after the first exposure to irradiation, lung tissue and peripheral blood samples were collected from the mice. Histological injury was analyzed, and inflammatory cell infiltration and interleukin (IL)-17A production in the lung tissues were quantified.

Results

Mice that received irradiation with concurrent administration of anti-PD-1 antibody had the highest histological score for RILI. In the murine lung tissues, the levels of PD-1 and IL-17A expression were increased in γδ T cells but not in the other CD3+ T cells after irradiation. Concurrent blockade of PD-1 enhanced IL-17A production from γδ T cells in the lung tissues after irradiation. In the mice with acute RILI, concurrent administration of anti-PD-1 antibody exaggerated pulmonary inflammation, with significantly increased levels of neutrophilic infiltration and IL-17A detected in both the lung and blood.

Conclusions

PD-1 could restrain IL-17A production from γδ T cells to modulate acute RILI. The concurrent administration of anti-PD-1 antibody aggravates the severity of acute RILI. More attention should be paid to pulmonary toxicity in patients undergoing thoracic RT with concurrent anti-PD-1 immunotherapy.

Keywords: Radiotherapy (RT), radiation-induced lung injury (RILI), programmed cell death 1 (PD-1), γδ T cells, interleukin-17A (IL-17A)

Introduction

Radiotherapy (RT) is a mainstay of treatment for thoracic neoplasms (1). Radiation-induced lung injury (RILI) is the most common dose-limiting complication associated with thoracic RT. Patients with RILI may suffer from cough, panting, dyspnea, or even respiratory failure, which can compromise the effect of this therapy (2,3).

Immune checkpoint inhibitors targeting programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) and programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) have revolutionized the clinical management of non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) (4). The synergistic efficacy of RT with PD-1/PD-L1 blockade has tremendously improved overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) rates among patients with NSCLC (5,6). However, the toxicity profile of RT with concurrent anti-PD-1 therapy in regard to non-malignant lung tissue has not been well defined.

PD-1 is an inducible inhibitory receptor expressed on activated effector T cells (7). T-cell function is significantly inhibited when PD-1 is engaged with PD-L1 or PD-L2, both of which are expressed on tumor cells or immune cells within tumors (8). Anti-PD-1/PD-L1 monoclonal antibodies effectively interdict the immune inhibitory signals, thereby recovering the immune response against the tumor (9). Blockade of PD-1/PD-L1 can also cause collateral damage in non-malignant tissues, which are referred to as immune-related adverse events (10,11). Immune-mediated pneumonitis is usually manageable. However, in a small number of cases, it results in the withdrawal of treatment, and occurrence of fulminant or lethal events (12,13). Considering the potential overlapping pulmonary toxicity of RT and anti-PD-1 therapy, we hypothesized that concurrent PD-1 blockade would exacerbate RILI.

The mechanisms underlying the potential synergistic adverse effects of thoracic RT and anti-PD-1 therapy involve several cytokines (14-16). Interleukin (IL)-17A, which is mainly produced by T helper 17 (Th17) cells and γδ T cells, is a newly discovered cytokine involved in lung immunity and mediates pro-inflammatory responses (17). Several studies have reported that irradiation induces an increase of Th17 cells (18,19). In various inflammatory conditions, the expression of PD-1 on γδ T cells is upregulated (20,21). Genetic deficiency of PD-1 in γδ T cells in the skin exacerbates psoriasiform dermatitis (20), while recombinant PD-L1 protein alleviates psoriatic inflammation by inhibiting γδ T cells (21). As γδ T cells are abundant in lung tissue (22), the role of IL-17A-producing γδ T cells in RILI needs to be addressed.

In this study, we established a mouse model to mimic lung irradiation and concurrent administration of anti-PD-1 antibody. We found that PD-1 expression on γδ T cells could restrain the production of IL-17A to modulate acute RILI. The concurrent administration of anti-PD-1 antibody aggravated the severity of acute RILI. Therefore, when RILI occurs, the administration of anti-PD-1 antibody should be carefully considered.

We present the following article in accordance with the ARRIVE reporting checklist (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/tlcr-20-838).

Methods

Animals

As the C57BL/6 model is suited for the analysis of RILI, we purchased 6 to 8-week-old male C57BL/6 mice from HFK Bioscience (Beijing, China). The mice were maintained in a specific pathogen-free (SPF) facility under a 12-hour light-dark cycle at 22–25 °C and acclimated for three days prior to the experiments. Experiments were performed under a project license (No. NCC2018A144) granted by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the National Cancer Center/Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (NCC/CH, CAMS, Beijing, China), in compliance with institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals.

Radiation schedule

Mice were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane inhalation, and immobilized in a dedicated mouse holder with a lead shield that allowed for selective thoracic irradiation. Based on the published literatures (16,23), we administrated the thoracic irradiation using a linear accelerator (Varian Medical Systems, Palo Alto, CA, USA) on the mice at a dose rate of 3 Gy/min with the regimen of 8 Gy ×3 on days 0, 1 and 2. The source-surface distance was 100 cm. The irradiation field was 4 cm × 2 cm. Mice were randomly assigned to different groups with the numbers of 5–12 for each time-point per group. Control mice underwent the same procedure and exposed to 0 Gy.

Antibody treatment

Mice were intraperitoneally injected with 10 mg/kg of either rat immunoglobulin G (IgG) isotype or rat anti-PD-1 antibody (Bio X Cell, West Lebanon, NH, USA) one day before irradiation and twice a week for three consecutive weeks thereafter, in order to maintain circulating levels in previous studies (24,25).

Histological analysis

Mice were euthanized by carbon dioxide (CO2) asphyxiation on days 3, 7, 14, and 28 after the first exposure to irradiation. The fixed left lungs were embedded in paraffin and sectioned for hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining. Based on the reports (26,27), the pathological grades of injury were evaluated blindly by two independent investigators, using the following criteria: 0= no lung abnormality; 1= presence of inflammation involving <25% of the lung parenchyma; 2= lesions involving 25–50% of the lung; 3= lesions involving >50% of the lung. The mean of the pathological grade for two sections was individually determined for each mouse.

After removal of the lungs, the cardiac vasculature was perfused with cold heparinized phosphate buffer saline (PBS) and the hearts were collected for histological analysis as described (28).

Cell preparation from various organs

Murine blood samples were drawn via cardiac puncture with heparin solution as an anticoagulant on the day of sacrifice. The right lungs of the mice were cut into small pieces and digested in 1 mg/mL collagenase D (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) and 40 U/mL DNase I (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) for 30 minutes at 37 °C while shaking, as previously reported (29), with minor modifications. After digestion, 10 mM EDTA was added to stop the enzymatic process. The lung and spleen tissues were triturated and filtered through 70 µm cell strainers. Erythrocytes were lysed in red blood cell lysing buffer (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA).

Flow cytometry

Single cell suspensions were labeled with Fixable Viability Dye and surface staining was subsequently performed. For analysis of neutrophils, cell suspensions were incubated with antibodies against CD45, Ly6G, and CD11b (30). To detect the expression of PD-1 on γδ T cells, cell suspensions were incubated with antibodies against CD45, CD3, γδ TCR, and PD-1 (29). For intracellular staining, cells suspensions were stimulated with 50 ng/mL phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) and 1 µg/mL ionomycin in the presence of 5 µg/mL brefeldin A for 5 hours. After stimulation, the harvested cells were firstly stained with CD45, CD3, and γδ TCR (29). Then the cells were fixed, permeabilized and stained with IL-17A. Stained cells were detected using a LSR-II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) and the results were analyzed by FlowJo software (Tree Star Inc., Ashland, OR, USA). The antibodies and reagents used for flow cytometry were purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA, USA) or BioLegend (San Diego, CA, USA).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

The concentration of IL-17A in plasma from the mice or cell culture supernatant was measured by a commercialized mouse IL-17A (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA) ELISA kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

IL-17A neutralization and recruitment of neutrophils

Lung interstitial liquid was prepared as reported previously (31) with modification. Briefly, each 100 mg lung tissue was cut into small pieces in 400 µL ice cold normal saline and incubated on ice for 15 minutes. Lung interstitial liquid was collected after centrifugation at 500 g for 10 minutes. To neutralize the activities of IL-17A, the lung interstitial liquid collected from one mouse was treated with 1 µg rat anti-IL-17A neutralizing antibodies (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA) at 37 °C for 2 hours. As a control, the lung interstitial liquid was treated with 1 µg rat IgG isotype in the same way. The treated lung interstitial liquid was then injected intraperitoneally into untreated mice. All peritoneal lavage cells were harvested 4 hours later, and the numbers of neutrophils were determined by flow cytometry.

RNA isolation and real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from the lung tissues using TRIzol (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The cDNA was synthesized using PrimeScript Reverse Transcription Reagent (Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan). The primers used for IL-17A quantification were as follows: forward 5'-TCCCTCTGTGATCTGGGAAG-3', reverse 5'-AGCATCTTCTCGACCCTGAA-3'. Quantification was performed using SYBR Premix Ex Taq (Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan) on an Applied Biosystems 7500 qPCR system (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Each sample was determined in duplicates. The relative mRNA levels were calculated based on GAPDH according to the report (31).

Magnetic activated cell sorting (MACS) and in vitro treatment

Standard laboratory protocols were used to prepare the splenocytes and isolate the γδ T cells by MACS using a TCRγδ isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) following the manufacturer’s instruction. We diluted the anti-PD-1 antibody (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA) into 10 and 20 µg/mL, the PD-L1-Fc fusion protein (PD-L1-Fc, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) into 5 and 10 µg/mL with PBS respectively. According to the report (21), The anti-PD-1 antibody and PD-L1-Fc were coated in 96-well plates overnight at 4 °C. In each well, 2×105 MACS-purified γδ T cells (purity was greater than 90.0%) were added, and cultured in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FBS with 5 µg/mL anti-CD3 antibody for 48 hours. In control group, the cells were cultured in the plate precoated with rat IgG. IL-17A-producing γδ T cells were examined by flow cytometry and the level of IL-17A in culture supernatant was determined by ELISA.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as means ± SD. Two-tailed Student’s t-tests were used to compare differences between two groups. Multiple group comparisons were analyzed by performing one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s tests. GraphPad Prism 6.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA) and SPSS 22.0 (IBM SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) were used to perform all these analyses. A two-sided P<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

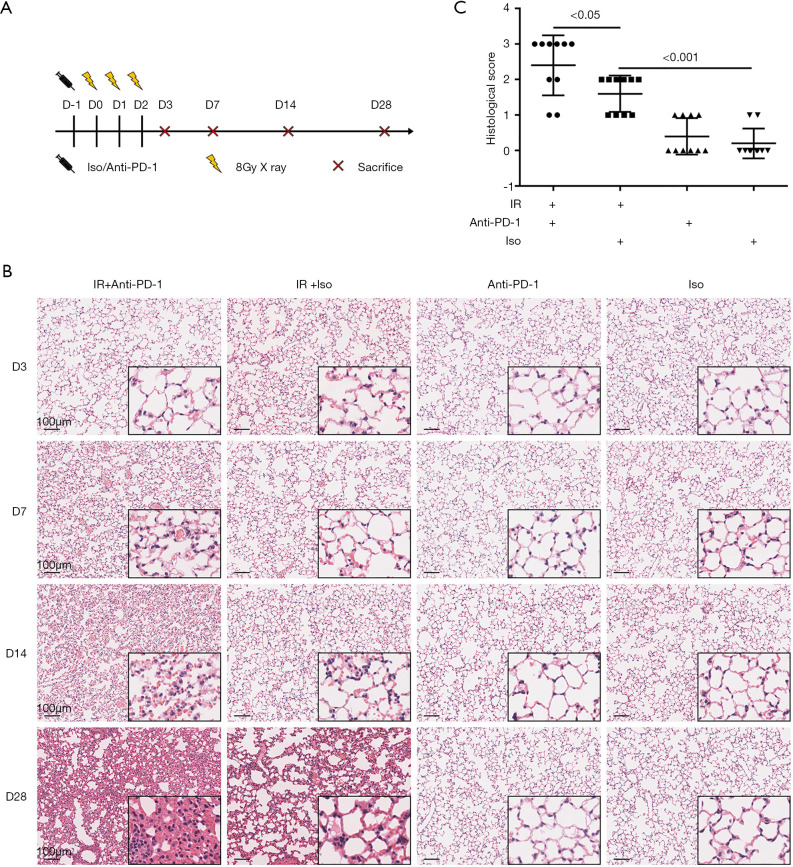

Concurrent administration of anti-PD-1 antibody aggravated acute RILI

While receiving 8 Gy ×3 of thoracic irradiation, the mice were concurrently administered rat anti-PD-1 antibody or IgG isotype (Figure 1A). We maintained the irradiated mice for 28 days and no death occurred during this period. Histopathological assessment of lung tissue injury following irradiation was carried out. It revealed that tissue injury was aggravated in a time-dependent manner. On day 3 post-irradiation, no tissue injury was apparent, while on day 7, alveoli collapse, lung capillary hyperemia, hemorrhage, and inflammatory exudate were observed (Figure 1B). We calculated the percentage of the section occupied by pulmonary inflammatory lesions and scored it according to published histological scoring criteria for RILI (26). On day 7 post-irradiation, the mice that received irradiation plus anti-PD-1 antibody demonstrated the most severe pulmonary injury, with lesions involving more than 50% of the lung. The mice that received irradiation plus anti-PD-1antibody had a higher histological score for RILI than those treated with irradiation plus isotype (Figure 1C). On days 14 and 28 post-irradiation, in the irradiated mice, inflammatory cell infiltration was increased and thickened alveolar septum was observed, which worsened when anti-PD-1 antibody was synchronously administrated (Figure 1B). On days 7 and 14 post-irradiation, no obvious heart injury was observed in the mice that received irradiation plus IgG or in combination with anti-PD-1 antibody (Figure S1). These results suggest that concurrent administration of anti-PD-1 antibody aggravates acute RILI.

Figure 1.

Concurrent administration of anti-PD-1 antibody aggravated acute RILI. (A) The experimental schedule. Rat anti-PD-1 antibody or rat IgG isotype was intraperitoneally administrated one day before irradiation and twice a week for three consecutive weeks thereafter. (B) Representative images of HE-stained lung tissues from different groups on days 3, 7, 14 and 28 after the first exposure to irradiation. Original magnification, 100×; inset magnification, 400×. (C) Histology scores of HE staining on day 7 post-irradiation. Each dot represents one mouse. D, day; Iso, IgG isotype; PD-1, programmed death 1; IR, irradiation; RILI, radiation-induced lung injury.

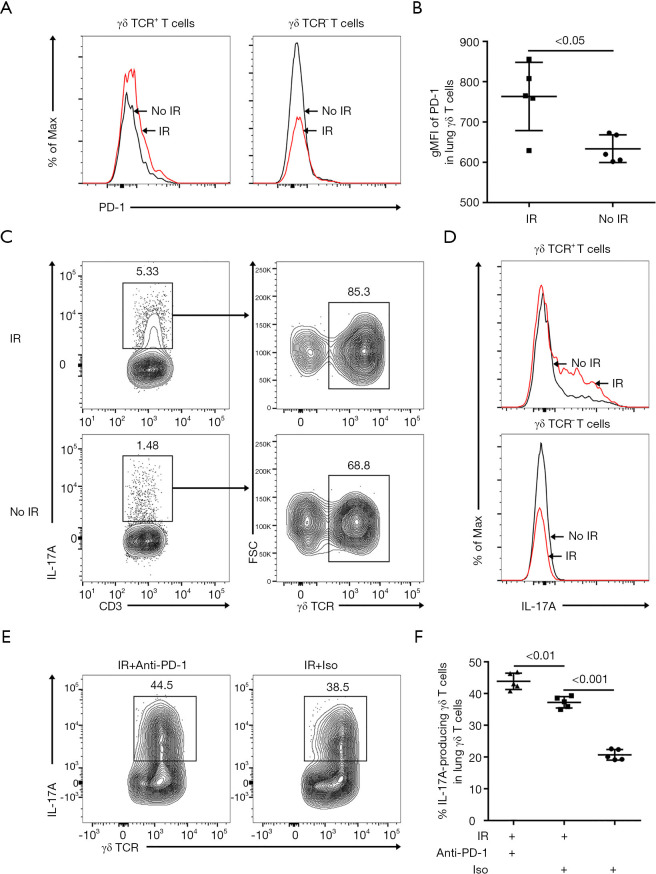

Irradiation enhanced PD-1 expression on γδ T cells in lung tissues

We harvested the lung tissues from the irradiated mice for flow cytometry analysis on day 7 post-irradiation. Among the CD3+ T cells, PD-1 expression was increased on γδ T cells but not on the other T cells after irradiation (Figure 2A,B). The potent pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-17A was mainly detected in γδ T cells at a steady state, and the production increased after irradiation (Figure 2C). Irradiation resulted in increased IL-17A production by γδ T cells, but no increased IL-17A production was detected in the other CD3+ T cells (Figure 2D). Compared with the irradiation plus isotype group, irradiation with concurrent administration of anti-PD-1 significantly enhanced IL-17A production in lung γδ T cells (Figure 2E,F).

Figure 2.

Irradiation enhanced the expression of PD-1 on γδ T cells in murine lung tissues. (A) Representative histograms of PD-1 expression on CD3+ γδ TCR+ T cells or CD3+γδ TCR- T cells in lung tissues on day 7 post-irradiation. (B) gMFI of PD-1 were analyzed in lung γδ T cells on day 7 post-irradiation (n=5). (C) CD3+ IL-17A+ T cells were further divided into T cell subsets: CD3+ γδ TCR+ T cells and CD3+ γδ TCR- T cells. (D) Representative histograms displaying intracellular IL-17A staining of CD3+ γδ TCR+ T cells or CD3+ γδ TCR- T cells in lung tissues on day 7 post-irradiation. (E and F) The relative frequency of IL-17A-producing γδ T cells in lung γδ T cells on day 7 post-irradiation (n=5). PD-1, programmed death 1; gMFI, geometric mean fluorescence intensity; IL-17A, interleukin-17A.

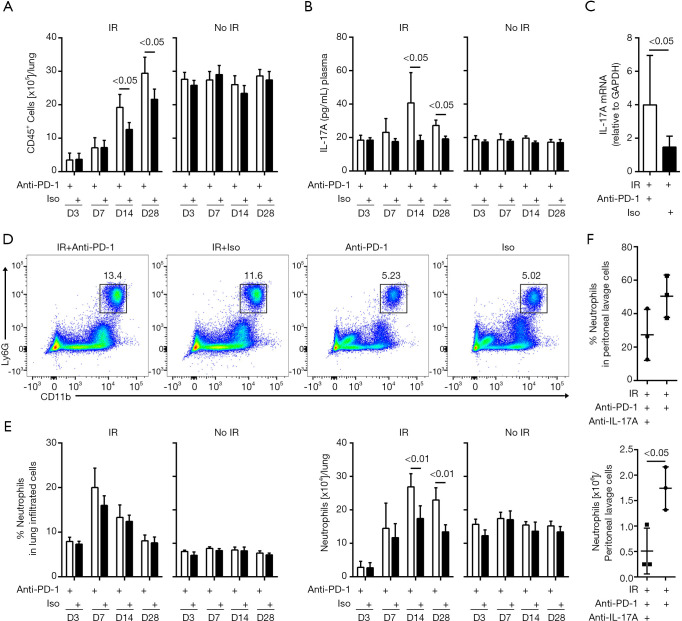

Concurrent administration of anti-PD-1 antibody exacerbated lung inflammation and increased IL-17A levels in the blood and lungs after irradiation

We then examined the recruitment of inflammatory cells into the irradiated lung tissues. In the non-irradiated mice, the total numbers of CD45+ leukocytes in the lung tissues were comparable between the anti-PD-1 antibody and isotype treated groups. In the irradiated mice, concurrent administration of anti-PD-1 antibody significantly increased leukocyte infiltration on days 14 and 28 post-irradiation (Figure 3A). The levels of IL-17A in the blood showed no alteration in the mice that received isotype alone or anti-PD-1 antibody alone. However, from day 7, IL-17A was gradually upregulated, reaching the peak on day 14, and remained higher on day 28 in the irradiated mice given anti-PD-1 antibody (Figure 3B). In the combined treatment group, the mRNA expression of IL-17A was increased in lung tissues on day 7 post-irradiation (Figure 3C and Figure S2). Flow cytometry analysis showed that anti-PD-1 therapy alone did not significantly alter the neutrophil (CD45+ Ly6G+ CD11b+) counts in the lung tissues compared to treatment with the isotype. In the irradiated mice, the total numbers of neutrophils in the lung tissues increased significantly when the mice received concurrent administration of anti-PD-1 antibody than those received isotype on days 14 and 28 post-irradiation (Figure 3D,E, Figure S3). On day 7 post-irradiation, lung interstitial liquids were collected from mice that received irradiation with concurrent anti-PD-1 therapy and were pretreated with IL-17A neutralizing antibodies. Compared with no treatment, neutralizing IL-17A significantly reduced the recruitment of neutrophils in peritoneal lavage fluid (Figure 3F). These data suggest that the combination of irradiation with anti-PD-1 therapy elevates the production of IL-17A and exacerbates the pulmonary inflammation caused by IL-17A.

Figure 3.

Concurrent administration of anti-PD-1 antibody increased lung inflammation in the acute RILI. (A) Total numbers of CD45+ leukocytes in the lung on days 3, 7, 14, and 28 post-irradiation. Empty bars indicate the mice received rat anti-PD-1 antibody. Filled bars indicate the mice received same amount of Isotype (n=5). (B) IL-17A concentration in the plasma at different time points determined by ELISA (n=5). (C) qRT-PCR analysis of IL-17A in lung tissues on day 7 post-irradiation (n =12 in IR + Anti-PD-1 group, n=6 in IR + Iso group). (D) Representative dot plots in flow cytometric analysis of CD45+Ly6G+CD11b+ neutrophils in the lung on day 14 post-irradiation. The percentage of neutrophils is based on the gating of total CD45+ leukocytes. (E) Graph showing percentages (left) and total numbers (right) of neutrophils in the lung on days 3, 7, 14, and 28 post-irradiation (n=5). (F) The percentages (upper) and total numbers (lower) of neutrophils in peritoneal lavage cells examined after IL-17A neutralization (n=3). PD-1, programmed death 1; RILI, radiation-induced lung injury; IL-17A, interleukin-17A; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

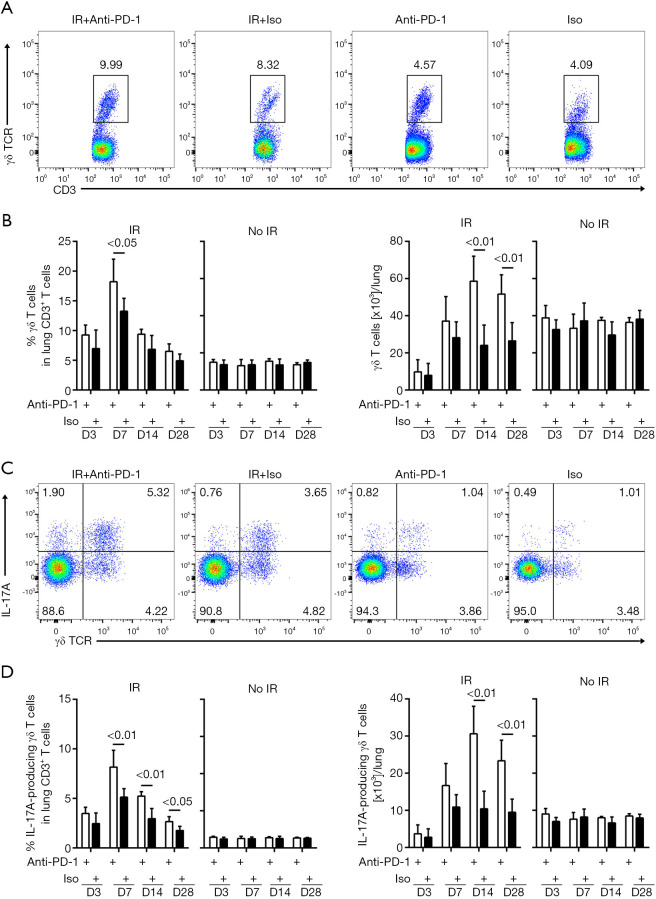

The numbers of IL-17A-producing γδ T cells were elevated in the lungs of mice administered irradiation and concurrent anti-PD-1 antibody

γδ T cells in lung tissues were further analyzed at different time-points after treatment. In the non-irradiated mice, flow cytometry analysis indicated no significant difference in the total numbers of γδ T cells (CD45+ CD3+ TCRγδ+) between the anti-PD-1 antibody and isotype-treated groups. In the irradiated mice, concurrent anti-PD-1 therapy resulted in significantly up-regulated numbers of lung γδ T cells on days 14 and 28 post-irradiation (Figure 4A,B, Figure S4). Among the CD3+ T cells, no significant change was observed in the frequency or absolute numbers of IL-17A-producing γδ T cells between the anti-PD-1 and isotype-treated mice. However, among the irradiated mice, the concurrent anti-PD-1 therapy mice were observed to have more IL-17A-producing γδ T cells in their lung tissues on days 14 and 28 post-irradiation (Figure 4C,D, Figure S5). Increased numbers of IL-17A-producing γδ T cells were also found in the peripheral blood and spleens of the combination group (Figures S6,S7).

Figure 4.

The numbers of IL-17A-producing γδ T cells increased with concurrent administration of anti-PD-1 antibody after irradiation. (A,C) Flow cytometry plots of lung CD45+ CD3+ γδ TCR+ T cells (A) and CD45+ CD3+ γδ TCR+ IL-17A+ T cells (C) on day 14 post-irradiation. The numbers were the percentage of objective cell among total CD3+ T cells. (B,D) The percentages (left) or numbers (right) of γδ T cells (B) and IL-17A-producing γδ T cells (D) were respectively enumerated by flow cytometry in lungs on days 3, 7, 14, and 28 post-irradiation (n=5). PD-1, programmed death 1.

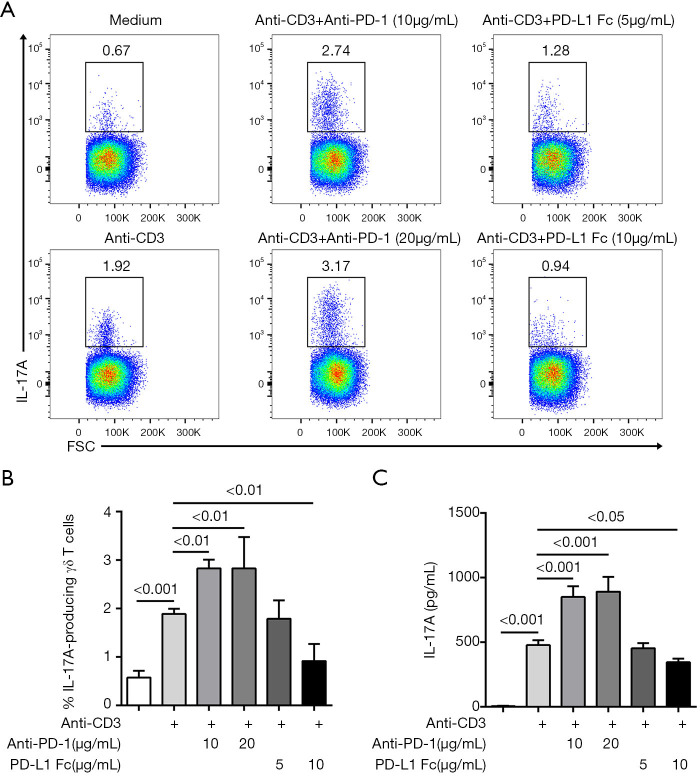

Anti-PD-1 antibody promotes anti-CD3-induced IL-17A production from γδ T cells

MACS-purified γδ T cells were stimulated with anti-CD3 antibody in the presence of anti-PD-1 antibody or PD-L1-Fc. After 48 hours of culture, the activation of γδ T cells was measured. Flow cytometry analysis showed that anti-PD-1 antibody significantly up-regulated the percentage of IL-17A-producing γδ T cells after stimulation with anti-CD3 antibody. ELISA measurement in the culture supernatant confirmed that anti-PD-1 antibody resulted in a higher level of IL-17A from γδ T cells. Conversely, a higher dose of PD-L1-Fc (10 µg/mL) exhibited the opposite effect (Figure 5). These results further demonstrated that the expression of PD-1 on γδ T cells suppresses the production of IL-17A.

Figure 5.

In vitro effects of anti-PD-1 antibody or PD-L1-Fc on γδ T cells. (A) IL-17A production was analyzed in γδ T cells. Representative dot plots of flow cytometry analysis are presented. The numbers represented the percentage of IL-17A-producing γδ T cells among total γδ T cells. (B) The relative frequency of IL-17A-producing γδ T cells in different culture systems (n=6). (C) IL-17A in the supernatant was determined by ELISA (n=6). PD-1, programmed death 1; IL-17A, interleukin-17A; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

Discussion

In the present study, we examined the safety of concurrent RT and anti-PD-1 immunotherapy by establishing a mouse model of acute RILI. The results indicated that concurrent administration of anti-PD-1 antibody with irradiation aggravated the severity of acute RILI. Further analysis indicated that an increased expression of PD-1 on γδ T cells in lung tissues might restrain their over-activation after irradiation. When anti-PD-1 antibody was concurrently administered in combination with RT, the production of IL-17A from γδ T cells was significantly enhanced, which mediated the aggravated severity of acute RILI.

RT is one of the major treatment approaches for patients with lung cancer (32). This conventional therapy is generally unable to subvert the immune tolerance of the tumor (33). Therapies targeting PD-1 and PD-L1, such as pembrolizumab, nivolumab and atezolizumab, release the brakes on activated T cells and renew their anti-cancer function. Immune checkpoint inhibitors have been approved for lung cancer treatment (34-36). As only about 20% of patients are able to benefit from the use of inhibitors, multimodal combinations, including the integration of RT, have been investigated to augment anti-tumor effects (37,38). Most of the available data indicate that the combination of RT and immune checkpoint blockade is generally safe, whereas others have reported significantly higher rates of pulmonary toxicity (39-42). We explored the effects of combined thoracic irradiation and anti-PD-1 therapy to better understand how non-malignant lung tissue may be affected during this combination therapy.

RILI involves the destruction of the lung structure and a sequence of inflammatory events, which is characterized by the recruitment of diverse immune cells and a perpetual cascade of cytokines/chemokines (3,43). Consistent with previous findings, we observed that irradiation triggered the infiltration of time-dependent leukocytes into the lung, most likely due to acute radiation responses, including DNA damage, reactive oxygen species (ROS) induction, and apoptosis (3,43). Concurrent administration of anti-PD-1 antibody increased the infiltration of radiation-induced inflammatory cells in the lung tissues, which conformed with the aggravated histopathological changes.

γδ T cells preferentially localize to mucosal surfaces, such as the skin, respiratory and digestive tracts (22). Furthermore, γδ T cells are largely pre-programmed in the thymus and are able to respond faster than Th17 cells. Once triggered, γδ T cells rapidly produce pro-inflammatory cytokines, thus they predominate in the early stages of inflammatory response (44). In this study, among the IL-17A-producing CD3+ T cells recruited upon irradiation in lung tissues, only γδ T cells significantly expressed IL-17A. Concurrent anti-PD-1 antibody application promoted the infiltration of IL-17A-producing γδ T cells in the irradiated lungs on days 14 and 28 post-irradiation. In line with the trend of increased numbers of IL-17A-producing γδ T cells, the level of IL-17A in the combined group increased gradually, peaking on day 14 post-irradiation and remained higher on day 28 post-irradiation. One hallmark function of IL-17A is attracting myeloid cells such as neutrophils to the injured tissue (17). Concurrent anti-PD-1 therapy significantly up-regulated the numbers of neutrophils in the lung tissues on days 14 and 28 post-irradiation. Lung interstitial liquid from the combined treatment group was intraperitoneally injected into untreated mice. In these mice, IL-17A was observed to recruit neutrophils into the peritoneal cavity and the chemotaxis was inhibited after IL-17A neutralization. All these data suggest that IL-17A production from γδ T cells plays an important role in the pathological manifestations of aggravated inflammation.

The coinhibitory receptor PD-1 is induced in activated T cells and increases after continuous or repetitive stimulation of T cells by antigen (7). Irradiation is well known to promote antigen liberation (45). Among the CD3+ T cells in this study, upregulated PD-1 expression was observed on γδ T cells in the lung tissues following thoracic irradiation. The results indicate that γδ T cells can be activated after irradiation, which may be attributed to the stimulation of radiation-induced antigens. Hoverer, it remains unclear which antigens activate γδ T cells via their T cell receptors in RILI. In vivo synchronous administration of anti-PD-1 antibody resulted in increased IL-17A production from γδ T cells after irradiation. In an in vitro experiment, we applied anti-CD3 antibodies to mimic the effect of radiation-induced antigens on naïve γδ T cells. Consistently, blockade of the PD-1/PD-Ls pathway further enhanced the secretion of IL-17A from γδ T cells after CD3 stimulation, whereas PD-L1-Fc showed the opposite effect. Taken together, these findings suggest that PD-1 expressed on activated γδ T cells after irradiation probably functions as a brake for RILI, and those cells may be further unleashed by anti-PD-1 therapy, thereby producing higher levels of IL-17A.

Reassuringly, available data, such as those from the PACIFIC trial, demonstrate that the rate of pulmonary toxicity in patients receiving RT and immunotherapy is not very high (6). However, participants in the PACIFIC clinical trial received radiochemotherapy before they received anti-PD-L1 treatment, and patients who suffered grade 2 or higher pneumonitis as a result of previous radiochemotherapy were routinely excluded from the clinical trial. In contrast, a multicenter analysis reported a relatively higher incidence of grade 3 pneumonitis in the concurrent RT and immune checkpoint inhibitor cohort (46). Whether the combination of RT and concurrent immune checkpoint inhibitors increases the risk of pulmonary toxicity currently remains to be answered. Our study provides evidence that the concurrent application of thoracic irradiation and anti-PD-1 antibody could intensify pulmonary toxicity. In another study, concurrent PD-1 inhibition and cardiac irradiation increased radiation-induced cardiac toxicity (RICT) (25). RICT is a recognized late sequela of thoracic RT (47). In the current study, we tried to address the acute toxicities associated with thoracic RT, such as acute pulmonary toxicity. Chronic toxicities including RICT and pulmonary fibrosis need to be explored in the future. Our experimental model may not truly reflect the management of lung cancer in clinical practice, and pulmonary toxicity should be monitored during treatment with thoracic RT and concurrent PD-1 inhibitors. Further verification of the potential effects of this combination is needed in a clinical setting.

Conclusions

In summary, we have provided evidence that PD-1 restrains IL-17A production from γδ T cells in the lung tissues to modulate acute RILI. The concurrent application of anti-PD-1 antibody aggravates acute RILI. We recommend that patients receiving a combination of thoracic RT and concurrent PD-1/PD-L1 blockade are monitored closely for pulmonary toxicity.

Supplementary

The article’s supplementary files as

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by Sanming Project of Medicine in Shenzhen (No. SZSM201612063), Medical Science and Technology Research Fund Project of Guangdong Province (No. A2020583), and Open Funding of the State Key Lab of Molecular Oncology (No. SKL-KF-2019-06).

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Experiments were performed under a project license (No. NCC2018A144) granted by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the National Cancer Center/Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (NCC/CH, CAMS, Beijing, China), in compliance with institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals.

Footnotes

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the ARRIVE reporting checklist. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/tlcr-20-838

Data Sharing Statement: Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/tlcr-20-838

Peer Review File: Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/tlcr-20-838

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/tlcr-20-838). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Atun R, Jaffray DA, Barton MB, et al. Expanding global access to radiotherapy. Lancet Oncol 2015;16:1153-86. 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00222-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanania AN, Mainwaring W, Ghebre YT, et al. Radiation-Induced Lung Injury: Assessment and Management. Chest 2019;156:150-62. 10.1016/j.chest.2019.03.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giuranno L, Ient J, De Ruysscher D, et al. Radiation-Induced Lung Injury (RILI). Front Oncol 2019;9:877. 10.3389/fonc.2019.00877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanna N, Johnson D, Temin S, et al. Systemic Therapy for Stage IV Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:3484-515. 10.1200/JCO.2017.74.6065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Theelen WSME, Peulen HMU, Lalezari F, et al. Randomized phase II study of pembrolizumab after stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) versus pembrolizumab alone in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer: The PEMBRO-RT study. JAMA Oncol 2019;5:1276-82. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.1478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antonia SJ, Villegas A, Daniel D, et al. Durvalumab after Chemoradiotherapy in Stage III Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2017;377:1919-29. 10.1056/NEJMoa1709937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okazaki T, Chikuma S, Iwai Y, et al. A rheostat for immune responses: the unique properties of PD-1 and their advantages for clinical application. Nat Immunol 2013;14:1212-8. 10.1038/ni.2762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun C, Mezzadra R, Schumacher TN. Regulation and Function of the PD-L1 Checkpoint. Immunity 2018;48:434-52. 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.03.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zou W, Wolchok JD, Chen L. PD-L1 (B7-H1) and PD-1 pathway blockade for cancer therapy: Mechanisms, response biomarkers, and combinations. Sci Transl Med 2016;8:328rv4. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad7118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baxi S, Yang A, Gennarelli RL, et al. Immune-related adverse events for anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 drugs: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2018;360:k793. 10.1136/bmj.k793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramos-Casals M, Brahmer JR, Callahan MK, et al. Immune-related adverse events of checkpoint inhibitors. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2020;6:38. 10.1038/s41572-020-0160-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Naidoo J, Wang X, Woo KM, et al. Pneumonitis in Patients Treated With Anti-Programmed Death-1/Programmed Death Ligand 1 Therapy. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:709-17. 10.1200/JCO.2016.68.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nishino M, Giobbie-Hurder A, Hatabu H, et al. Incidence of Programmed Cell Death 1 Inhibitor-Related Pneumonitis in Patients With Advanced Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol 2016;2:1607-16. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.2453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xue J, Du S, Dicker AP, et al. Anti-PD-1 Immunotherapy Potentiates the Radiation-Induced Lung Injury. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2018;102:S205. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2018.07.110 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schoenfeld JD, Nishino M, Severgnini M, et al. Pneumonitis resulting from radiation and immune checkpoint blockade illustrates characteristic clinical, radiologic and circulating biomarker features. J Immunother Cancer 2019;7:112. 10.1186/s40425-019-0583-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang F, Luo Y, Tian X, et al. Impact of Radiotherapy Concurrent with Anti-PD-1 Therapy on the Lung Tissue of Tumor-Bearing Mice. Radiat Res 2019;191:271-7. 10.1667/RR15182.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McGeachy MJ, Cua DJ, Gaffen SL. The IL-17 Family of Cytokines in Health and Disease. Immunity 2019;50:892-906. 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.03.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paun A, Kunwar A, Haston CK. Acute adaptive immune response correlates with late radiation-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice. Radiat Oncol 2015;10:45. 10.1186/s13014-015-0359-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cappuccini F, Eldh T, Bruder D, et al. New insights into the molecular pathology of radiation-induced pneumopathy. Radiother Oncol 2011;101:86-92. 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.05.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Imai Y, Ayithan N, Wu X, et al. Cutting Edge: PD-1 Regulates Imiquimod-Induced Psoriasiform Dermatitis through Inhibition of IL-17A Expression by Innate gammadelta-Low T Cells. J Immunol 2015;195:421-5. 10.4049/jimmunol.1500448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim JH, Choi YJ, Lee BH, et al. Programmed cell death ligand 1 alleviates psoriatic inflammation by suppressing IL-17A production from programmed cell death 1-high T cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2016;137:1466-76.e3. 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.11.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheng M, Hu S. Lung-resident gammadelta T cells and their roles in lung diseases. Immunology 2017;151:375-84. 10.1111/imm.12764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dewan MZ, Galloway AE, Kawashima N, et al. Fractionated but not single-dose radiotherapy induces an immune-mediated abscopal effect when combined with anti-CTLA-4 antibody. Clin Cancer Res 2009;15:5379-88. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Myers CJ, Lu B. Decreased Survival After Combining Thoracic Irradiation and an Anti-PD-1 Antibody Correlated With Increased T-cell Infiltration Into Cardiac and Lung Tissues. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2017;99:1129-36. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2017.06.2452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Du S, Zhou L, Alexander GS, et al. PD-1 Modulates Radiation-Induced Cardiac Toxicity through Cytotoxic T Lymphocytes. J Thorac Oncol 2018;13:510-20. 10.1016/j.jtho.2017.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuwano K, Hagimoto N, Kawasaki M, et al. Essential roles of the Fas-Fas ligand pathway in the development of pulmonary fibrosis. J Clin Invest 1999;104:13-9. 10.1172/JCI5628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heinzelmann F, Jendrossek V, Lauber K, et al. Irradiation-induced pneumonitis mediated by the CD95/CD95-ligand system. J Natl Cancer Inst 2006;98:1248-51. 10.1093/jnci/djj335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krüse JJ, Zurcher C, Strootman EG, et al. Structural changes in the auricles of the rat heart after local ionizing irradiation. Radiother Oncol 2001;58:303-11. 10.1016/S0167-8140(00)00327-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jin C, Lagoudas GK, Zhao C, et al. Commensal Microbiota Promote Lung Cancer Development via γδ T Cells. Cell 2019;176:998-1013.e16. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.12.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Venosa A, Katzen J, Tomer Y, et al. Epithelial Expression of an Interstitial Lung Disease-Associated Mutation in Surfactant Protein-C Modulates Recruitment and Activation of Key Myeloid Cell Populations in Mice. J Immunol 2019;202:2760-71. 10.4049/jimmunol.1900039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen K, Wu Z, Zhao H, et al. XCL1/Glypican-3 Fusion Gene Immunization Generates Potent Antitumor Cellular Immunity and Enhances Anti-PD-1 Efficacy. Cancer Immunol Res 2020;8:81-93. 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-19-0210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Postmus PE, Kerr KM, Oudkerk M, et al. Early and locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC): ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2017;28:iv1-21. 10.1093/annonc/mdx222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barker HE, Paget JT, Khan AA, et al. The tumour microenvironment after radiotherapy: mechanisms of resistance and recurrence. Nat Rev Cancer 2015;15:409-25. 10.1038/nrc3958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reck M, Rodriguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, et al. Pembrolizumab versus Chemotherapy for PD-L1-Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2016;375:1823-33. 10.1056/NEJMoa1606774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brahmer J, Reckamp KL, Baas P, et al. Nivolumab versus Docetaxel in Advanced Squamous-Cell Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2015;373:123-35. 10.1056/NEJMoa1504627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rittmeyer A, Barlesi F, Waterkamp D, et al. Atezolizumab versus docetaxel in patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (OAK): a phase 3, open-label, multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2017;389:255-65. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32517-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gong J, Le TQ, Massarelli E, et al. Radiation therapy and PD-1/PD-L1 blockade: the clinical development of an evolving anticancer combination. J Immunother Cancer 2018;6:46. 10.1186/s40425-018-0361-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kordbacheh T, Honeychurch J, Blackhall F, et al. Radiotherapy and anti-PD-1/PD-L1 combinations in lung cancer: building better translational research platforms. Ann Oncol 2018;29:301-10. 10.1093/annonc/mdx790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Verma V, Cushman TR, Selek U, et al. Safety of Combined Immunotherapy and Thoracic Radiation Therapy: Analysis of 3 Single-Institutional Phase I/II Trials. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2018;101:1141-8. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2018.04.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hwang WL, Niemierko A, Hwang KL, et al. Clinical Outcomes in Patients With Metastatic Lung Cancer Treated With PD-1/PD-L1 Inhibitors and Thoracic Radiotherapy. JAMA Oncol 2018;4:253-5. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.3808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shaverdian N, Lisberg AE, Bornazyan K, et al. Previous radiotherapy and the clinical activity and toxicity of pembrolizumab in the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer: a secondary analysis of the KEYNOTE-001 phase 1 trial. Lancet Oncol 2017;18:895-903. 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30380-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tamiya A, Tamiya M, Nakahama K, et al. Correlation of Radiation Pneumonitis History Before Nivolumab with Onset of Interstitial Lung Disease and Progression-free Survival of Patients with Pre-treated Advanced Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. Anticancer Res 2017;37:5199-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schaue D, McBride WH. T lymphocytes and normal tissue responses to radiation. Front Oncol 2012;2:119. 10.3389/fonc.2012.00119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Papotto PH, Ribot JC, Silva-Santos B. IL-17(+) gammadelta T cells as kick-starters of inflammation. Nat Immunol 2017;18:604-11. 10.1038/ni.3726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tang C, Wang X, Soh H, et al. Combining radiation and immunotherapy: a new systemic therapy for solid tumors? Cancer Immunol Res 2014;2:831-8. 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tian S, Switchenko JM, Buchwald ZS, et al. Lung Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy and Concurrent Immunotherapy: A Multicenter Safety and Toxicity Analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2020;108:304-13. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2019.12.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Simone CB, 2nd. Thoracic Radiation Normal Tissue Injury. Semin Radiat Oncol 2017;27:370-7. 10.1016/j.semradonc.2017.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The article’s supplementary files as