Abstract

Context

Current evidence on determinants of adverse health outcomes in patients with adrenal insufficiency (AI) is scarce, especially in regards to AI subtypes.

Objective

To determine predictors of adverse outcomes in different subtypes of AI.

Design and Setting

Cross-sectional survey study at 2 tertiary centers.

Participants

A total of 696 patients with AI: primary AI (PAI, 42%), secondary AI (SAI, 32%), and glucocorticoid-induced AI (GIAI, 26%).

Intervention

Patient-centered questionnaire.

Main Outcome Measures

Patients’ knowledge, self-management of AI, self-perceived health, and adverse outcomes.

Results

The incidence rate of adrenal crisis was 24/100 patient-years with 44% experiencing at least 1 adrenal crisis since diagnosis (59% in PAI vs 31% in SAI vs 37% in GIAI, P < .0001). All patients described high degrees of discomfort with self-management and receiving prompt treatment. Patients with PAI were most likely to develop adrenal crises (adjusted OR 2.8, 95% CI 1.9-4.0) despite reporting better self-perceived health (adjusted OR 3.3, 95% CI 2.1-5.3), understanding of their diagnosis (89% vs 74-81% in other subtypes, P = .002), higher comfort with self-management (62% vs 52-61% in other sub types, P = .005), and higher likelihood to receive prompt treatment for adrenal crises in the emergency department (42% vs 19-30% in other subtypes, P < .0001).

Conclusions

Patients with AI reported high degrees of discomfort with self-management and treatment delays when presenting with adrenal crises. Despite better self-perceived health and understanding of diagnosis, patients with PAI experienced the highest frequency of adrenal crises. A multidimensional educational effort is needed for patients and providers to improve the outcomes of all subtypes of AI.

Keywords: glucocorticoid therapy, adrenal crisis, diagnosis, management, healthcare delivery

Adrenal insufficiency (AI) is a chronic endocrine disorder that often necessitates life-long glucocorticoid replacement. Based on the underlying etiology, it can be classified as primary adrenal insufficiency (PAI) or secondary adrenal insufficiency (SAI) (1). PAI results from intrinsic disease to the adrenal cortex, most commonly due to autoimmune adrenalitis (2). SAI is caused by insufficient or deficient corticotropin production, predominantly due to pituitary disease (1). The most common cause of AI is glucocorticoid-induced adrenal insufficiency (GIAI), a unique form of SAI caused by long-term iatrogenic glucocorticoid use (3).

Patients with AI have reported impaired quality of life and substantial adverse health outcomes based on several studies conducted in Europe, with fairly consistent scores across the studies (4-7). However, data on the determinants of adverse outcomes in AI subtypes have been discrepant. One cross-sectional study revealed poor self-reported health status in patients with PAI and SAI after adjustment for age and sex compared with the general population (4). Another study in a cohort of patients with autoimmune adrenalitis demonstrated worse self-reported health scores with older age and in women after adjusting for age, sex, country, and comorbidities (6). One other study revealed that health-related quality of life did not differ by subtype of AI or glucocorticoid schedule, but was worse if taking a supraphysiologic glucocorticoid dosage (8). Two Norwegian registry-based studies reported reduced working ability in 12% to 19% of patients with isolated Addison disease, and 36% in patients with autoimmune polyglandular syndrome (9, 10). Other studies reported a higher impact on working ability (4) and a higher annual healthcare expenditure due to hospitalizations and outpatient visits in patients with SAI (7). Moreover, although adrenal crisis was reported to occur more frequently in patients with a longer duration of AI or a previous history of adrenal crisis (11, 12), its association with a particular subtype of AI was unclear.

Further clarification is needed to understand health outcomes and determinants of poor self-perceived health in patients with AI, and how this may vary between PAI, SAI, and GIAI. Moreover, understanding how these factors affect non-European populations with AI is needed. The objective of this multisite study was to comprehensively evaluate self-reported disease burden in US patients with AI, and relate it to critical components including subtypes of AI, specific medical management, and systems of social support.

Patients and Methods

Participants

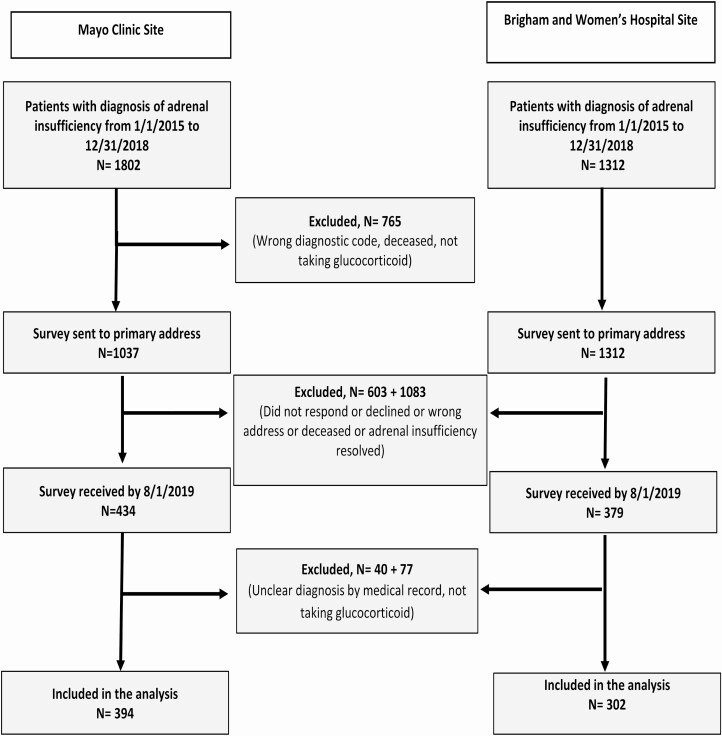

After obtaining approval from Institutional Review Boards of Mayo Clinic (Rochester, MN, USA) and Brigham and Women’s Hospital (Boston, MA, USA), we identified all potential adult patients with AI (N = 3264) from January 1, 2015, to December 31, 2018, through an institutional registry for AI diagnosis or because they were personally seen by the authors and known to have AI (Fig. 1). In total, 2349 patients were sent the survey either by postal mail, or by e-mail using a direct Research Electronic Data Capture link (13). Among 813 responders (35% response rate), 117 patients were excluded after reporting AI recovery, and 696 patients were included in the study. Participants’ responses were linked to their medical records to verify diagnosis and treatment concordance, as well as relevant comorbidities. We categorized AI into PAI, SAI, and GIAI. Reported glucocorticoids other than hydrocortisone (HC) were converted to HC equivalent: 1 mg of prednisone and prednisolone as 4 mg of HC, and 1 mg of dexamethasone as 25 mg of HC (14). Total daily glucocorticoid dose was calculated, and defined as supraphysiological if HC daily equivalent was >25 mg (15).

Figure 1.

Participant inclusion flow diagram.

Survey

The initial survey was constructed with input from coauthors and a panel of patients with AI. The final version contained demographic information, data on initial diagnosis of AI, data on health since initial diagnosis, comorbidities, symptoms, management including during crises, interest in patient support group and future research, and feedback to study investigators (all supplementary material and figures are located in a digital research materials repository (16)). “Adrenal crisis” in the survey referred to presentations to the emergency room to receive parenteral glucocorticoids (16). Patient “self-perceived health status” was determined (16) dichotomously as “good” (for those who answered “excellent,” “very good,” or “good”) or “poor” (for those who answered “fair” or “poor”).

Statistical analysis

Data from 2 participating sites were combined on September 1, 2019, and analyzed using the JMP, version 14.1.0 (SAS Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Figures were generated with GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). Variables were assessed for normality by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Non-normal distributed variables were described with median and interquartile range (IQR). For continuous variables, comparisons between PAI, SAI, and GIAI were performed using the Kruskal–Wallis test, and for categorical variables comparisons were made using the chi-squared test. Predictors of adverse outcomes were analyzed using logistic regression. P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Participants

The overall response rate was 35%, without major differences in age, sex, race, and subtypes of AI between responders and nonresponders (16). Of 696 participants, 291 (41.8%) had PAI, 226 (32.5%) had SAI, and 179 (25.7%) had GIAI. Median age at the time of survey completion was 58 (IQR 43-67) years, 440 (63.6%) were women and 643 (92.8%) were Caucasians (Table 1). When comparing between the 2 participating sites, differences were found in age at the time of AI diagnosis, duration of AI, and types of glucocorticoid used (16).

Table 1.

Diagnosis of adrenal insufficiencya

| Parameter | PAI (N = 291) |

SAI (N = 226) |

GIAI (N = 179) |

Total (N = 696) |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, female | 187 (64.3) | 124 (55.1) | 129 (73.3) | 440 (63.6) | .00080 | |

| Age at diagnosis, years, median, IQR | 37 (22-50) | 51 (36-61) | 54 (40-62) | 46 (32-59) | <.0001 | |

| Race, Caucasian | 278 (96.2) | 202 (89.4) | 163 (91.6) | 643 (92.8) | .0095 | |

| Study Site | Mayo Clinic | 156 (53.6) | 136 (60.2) | 102 (57.0) | 394 (56.6) | 0.32 |

| Brigham and Women’s Hospital | 135 (46.4) | 90 (39.8) | 77 (43.0) | 302 (43.4) | ||

| Number of symptoms at time of diagnosisb, median, IQR | 5 (2-8) | 3 (1-5) | 4 (3-6) | 4 (2-7) | <.0001 | |

| Number of autoimmune diagnosesc, median, IQR | 1 (1-2) | 1 (1-2) | 1 (1-2) | 1 (1-2) | .56 | |

| Needed to see more than one physician for diagnosis | 151 (66.5) | 109 (59.2) | 92 (66.2) | 352 (64) | .26 | |

| Years elapsed of undiagnosed symptoms before diagnosis, median, IQR | 1 (0-3) | 1 (0-4) | NA | 1 (0-3) | .81 | |

| Years since diagnosis, median, IQR | 10 (3-26) | 4 (2-9) | 3 (1-6) | 5 (2-13) | <.0001 | |

| Discordance in patient reported and documented diagnoses | 21 (7.5) | 33 (16.3) | 11 (7.0) | 65 (10.1) | .0022 | |

| Patient unaware of their diagnosis | 11 (3.8) | 23 (10.2) | 21 (11.7) | 55 (7.9) | .0025 |

Data are presented as n (%) unless stated otherwise.

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; PAI, primary adrenal insufficiency; SAI, secondary adrenal insufficiency; GIAI, glucocorticoid-induced adrenal insufficiency.

a Total participants (N) may not have answered all questions, in which case percentages listed in table are reflective of total number of respondents for individual questions. Excluded 9 patients with unknown/other adrenal insufficiency and those not taking glucocorticoids.

b Symptoms included any of the following: fatigue, skin darkening, weight loss, decreased appetite, salt cravings, fainting, low blood pressure, low blood sugar, muscle weakness, muscle cramping, mental fogginess or confusion, joint pains, diarrhea, or other previously unmentioned symptoms.

c Autoimmune diagnoses included any of the following: hyperthyroidism (Graves’ disease), hypothyroidism (Hashimoto’s thyroiditis), hypoparathyroidism, type 1 diabetes, vitiligo, celiac disease, hypogonadism, fungal infection, myasthenia gravis, pernicious anemia, alopecia, lupus, scleroderma, rheumatoid arthritis, other previously unnamed autoimmune condition.

When initially diagnosed with AI, patients with PAI were younger (median 37 years, IQR 22-50) than patients with SAI (median 51 years, IQR 36-61) or GIAI (median 54 years, IQR 40-62), P < .0001. Patients reported symptoms suggestive of AI for a median of 1 year (IQR 0-3 years) prior to diagnosis, with a higher number of symptoms in patients with PAI, indicating a more severe presentation than other subtypes (Table 1). A majority of patients with PAI (77%) had at least 1 autoimmune comorbidity, with autoimmune thyroid disease (Graves’ disease or Hashimoto’s thyroiditis) being most common (60%) (16).

Patients with PAI and GIAI had better awareness of their diagnosis when compared with those with SAI (concordance between self-reported diagnosis and diagnosis confirmed from the medical record was 92% and 93%, respectively, vs 84% in patients with SAI). Surprisingly, 8% of the total participants self-reported having the wrong AI subtype, or not knowing the subtype of AI (4% in patients with PAI vs 11% in patients with other subtypes, P = .0025), reflecting current gaps in ensuring patient education and counseling on their disease (Table 1).

Management of adrenal insufficiency

At the time of survey, patients reported a median duration of AI of 5 years (IQR 2-13), longest in patients with PAI (median of 10 years vs 4 and 3 years in patients with SAI and GIAI, respectively, P = .0001) (Table 2). Patients were most commonly treated with hydrocortisone (445, 66%), with 192 (29%) patients on prednisone, 8 (1%) on dexamethasone, and 26 (4%) on a combination regimen. In patients with PAI and SAI, hydrocortisone was the most commonly used glucocorticoid (72% and 73%, respectively), while patients with GIAI reported an almost equal proportion taking hydrocortisone and prednisone (49% and 45%). Patients with PAI reported the highest median HC equivalent daily replacement of 25 mg (IQR 20-30) versus median of 20 mg (IQR 15-25) in patients with SAI, and median of 20 mg (IQR 15-30) in patients with GIAI (P < .0001) (Table 2). Fludrocortisone replacement was reported in 249 (87%) of patients with PAI, but also in 3% and 9% of patients with SAI and GIAI, respectively (Table 2). Dehydroepiandrosterone therapy was reported only in 394 patients, with 31 (8%) reporting daily supplementation (all women). In addition, 534 (78%) patients reported taking over-the-counter supplements including vitamins, fish oil, probiotics, zinc, CoQ10, and omega-3. Nonpharmacologic complementary therapy was reported in 195 (38%) patients and included acupuncture, chiropractor, homeopathic, or naturopathic therapies, dietary modification therapy, and reflexology (Table 2). Patients using nonpharmacologic complementary therapies reported a higher number of adrenal crises and worse self-perceived health (16).

Table 2.

Management of adrenal insufficiencya

| Parameter | PAI (N = 291) |

SAI (N = 226) |

GIAI (N = 179) |

Total (N = 696) |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current age, years, median, IQR | 56 (41-66) | 58 (43-68) | 60 (47-68) | 58 (43-67) | .030 | |

| Years since diagnosis, years, median, IQR | 10 (3-26) | 4 (2-9) | 3 (1-6) | 5 (2-13) | .00010 | |

| Duration ≥5 years since diagnosis | 196 (69.3) | 95 (43.0) | 66 (39.5) | 357 (53.2) | <.0001 | |

| Difficulty of management since diagnosis | Easier | 174 (61.5) | 129 (61.1) | 87 (51.8) | 390 (58.9) | .0054 |

| No difference | 57 (20.1) | 52 (24.6) | 32 (19.1) | 141 (21.3) | ||

| Harder | 52 (18.4) | 30 (14.2) | 49 (29.2) | 131 (19.8) | ||

| Type of glucocorticoid | Hydrocortisone | 204 (71.6) | 159 (72.9) | 82 (48.8) | 445 (66.3) | <.0001 |

| Prednisone/Prednisolone | 65 (22.8) | 51 (23.4) | 76 (45.2) | 192 (28.6) | ||

| Dexamethasone | 5 (1.8) | 1 (0.5) | 2 (1.2) | 8 (1.2) | ||

| Combination regimen | 11 (3.9) | 7 (3.2) | 8 (4.8) | 26 (3.9) | ||

| Daily hydrocortisone equivalent dose, milligram, median, IQR | 25 (20-30) | 20 (15-25) | 20 (15-30) | 20 (16-30) | <.0001 | |

| On supraphysiologic dose of glucocorticoid (>25 mg HC)b | 100 (35.1) | 38 (17.4) | 57 (33.9) | 195 (29.1) | <.0001 | |

| On fludrocortisone | 249 (86.8) | 6 (2.8) | 15 (8.5) | 270 (39.6) | <.0001 | |

| Injectable glucocorticoid at home | 222 (76.8) | 142 (63.4) | 92 (51.7) | 456 (66.0) | <.0001 | |

| Comfortable with glucocorticoid IM self-injection | 100 (66.7) | 77 (58.8) | 65 (69.2) | 242 (64.5) | .22 | |

| Wearing medical alert gear | 238 (82.6) | 158 (70.2) | 102 (57.6) | 498 (72.2) | <.0001 | |

| Symptoms, median, IQR | Under-replacement symptomsc | 2 (1-4) | 2 (1-5) | 4 (2-6) | 2 (1–5) | <.0001 |

| Over-replacement symptomsd | 1 (0-2) | 1 (0-2) | 1 (0-3) | 1 (0–2) | .00030 | |

| Comorbidities related to glucocorticoid excesse | 1 (0-1) | 0 (0-1) | 1 (0-1) | 1 (0-1) | .25 | |

| Stress dose used in last 1 year | Median, IQR | 3 (1-6) | 2 (0-5) | 3 (1-6) | 2 (1–6) | .012 |

| ≥3 use per year | 155 (54.0) | 91 (41.0) | 88 (50.9) | 334 (49.0) | .012 | |

| Used as advisedf | 137 (59.6) | 95 (62.1) | 89 (69.5) | 321 (62.8) | .17 | |

| Adrenal crises per person-year in all patients, median, IQR | 0.07 (0-0.25) | 0 (0-0.14) | 0 (0-0.33) | 0 (0-0.23) | <.0001 | |

| Adrenal crises since diagnosis ≥1 | 169 (58.5) | 69 (31.4) | 64 (37.2) | 302 (44.4) | <.0001 | |

| Adrenal crises per person-year in those with ≥1 adrenal crisis, median, IQR | 0.20 (0.10-0.39) | 0.40 (0.17-0.67)) | 0.50 (0.17-1.0) | 0.25 (0.13-0.50) | <.0001 | |

| ER visit due to adrenal crisis | ER able to provide timely treatment | 70 (42.4) | 20 (30.3) | 11 (19.3) | 101 (35.1) | <.0001 |

| ER with treatment after explanation | 77 (46.7) | 28 (42.4) | 25 (43.9) | 130 (45.1) | ||

| ER with delays in treatment | 18 (10.9) | 18 (27.3) | 21 (36.8) | 57 (19.8) | ||

| Use of nonprescription supplements other than DHEA | 212 (74.1) | 179 (79.9) | 143 (80.8) | 534 (77.7) | .16 | |

| Use of nonpharmacologic treatmentg | 79 (38.0) | 59 (34.1) | 57 (42.5) | 195 (37.9) | .32 | |

| Financial impact | Inability to work due to medical condition in patients <65 years old | 18 (8.9) | 17 (11.4) | 11 (9.9) | 46 (1.0) | 0.74 |

| Cause financial burden | 119 (41.3) | 100 (44.8) | 83 (48.3) | 302 (44.2) | 0.34 | |

| Feeling poor general health | 63 (22.0) | 80 (35.4) | 103 (59.2) | 246 (35.8) | <.0001 | |

| Support for AI | Family or friend available during adrenal crisis | 225 (95.3) | 131 (80.4) | 108 (83.7) | 464 (87.9) | <0.0001 |

| Difficult to explain AI to family and friends | 105 (36.1) | 88 (38.9) | 78 (43.6) | 271 (38.9) | 0.27 | |

| Good support from health insurance company | 252 (88.4) | 181 (83.0) | 133 (79.6) | 566 (84.5) | 0.035 | |

| Interested in patient’s disease group | 223 (78.3) | 141 (62.4) | 125 (71.8) | 489 (71.4) | 0.00040 |

Data are presented as n (%) unless stated otherwise.

Abbreviations: ER, emergency room; HC, hydrocortisone; IQR, interquartile range; PAI, primary adrenal insufficiency; SAI, secondary adrenal insufficiency; GIAI, glucocorticoid-induced adrenal insufficiency; DHEA, dehydroepiandrosterone.

a Total participants (N) may not have answered all questions, in which case percentages listed in table are reflective of total number of respondents for individual questions. Excluded 9 patients with unknown/other adrenal insufficiency and those not taking glucocorticoids.

b Daily glucocorticoid dose expressed as milligrams of hydrocortisone equivalents

c Under-replacement symptoms included any of the following: fatigue, skin darkening, weight loss, decreased appetite, salt-craving, fainting, diarrhea, hypoglycemia, hypotension, muscle weakness or cramping, confusion, joint pain.

d Over-replacement symptoms included any of the following: hypertension, hyperglycemia, irritability, insomnia, leg swelling, weight gain.

e Glucocorticoid excess defined as: presence of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, heart attack or stroke, osteoporosis or osteopenia, or fragility fracture

f Advised indications for stress dose glucocorticoids include: fever, pneumonia or other infection, gastrointestinal illness (nausea/vomiting/diarrhea), surgery or medical procedure, and planned chemotherapy/radiation/therapy.

g Non-pharmacological treatments included: acupuncture, chiropractor, homeopathic/naturopathic therapy, dietary modification therapy, reflexology and other.

When asked about symptoms suggestive of glucocorticoid under-replacement (fatigue, skin darkening, weight loss, decreased appetite, salt-craving, fainting, diarrhea, hypoglycemia, hypotension, muscle weakness or cramping, confusion, or joint pain), patients with GIAI reported the highest number of symptoms (median of 4 vs 2 in patients with PAI and SAI, P < .0001). Similarly, patients with GIAI also reported a higher number of symptoms suggestive of glucocorticoid over-replacement (hypertension, hyperglycemia, irritability, insomnia, leg swelling, or weight gain), P = .0003 (Table 2).

Since the initial diagnosis, and when adjusted for the duration of AI, 303 (61%) patients with PAI and SAI reported that self-management of AI had become easier compared with 87 (52%) patients with GIAI (P = .0052). Patients with PAI reported receiving better support from family or friends, as well as medical insurance company. Nevertheless, 39% patients reported difficulties explaining their diagnosis and management to family and friends, similar between three AI subtypes (Table 2).

Adrenal crisis

Overall, since the diagnosis of AI, the mean incidence rate of adrenal crisis necessitating emergency department visit was 24/100 patient-years. Patients with PAI were more likely to use stress doses of glucocorticoid within ≥3 times in the 12 months prior to completing the survey when compared to patients with SAI and GIAI (54% vs 41% vs 51%, P = .012). They also had the highest number of adrenal crises since diagnosis, as 59% experienced at least 1 adrenal crisis since diagnosis, as opposed to 31% and 37% in patients with SAI and GIAI, respectively (Table 2). When accounting for the duration of AI, patients with PAI were still more likely to have an adrenal crisis (median of 0.07 person-year vs 0 person-years in SAI and GIAI). However, in patients who experienced more than 1 adrenal crisis, patients with PAI reported fewer recurrent adrenal crises (median of 0.2 person-years vs 0.4 and 0.5 person-years in patients with SAI and GIAI respectively, P < .0001) (Table 2). When asked about their visits to the emergency department for adrenal crisis, only 42% patients with PAI reported receiving prompt treatment, with the rest reporting either some delay with time spent explaining the need for stress-dosing of glucocorticoids (47%), or not being understood by the provider despite explanation, resulting in a significant delay in treatment(11%). The proportion of patients who reported ever having a negative experience in the emergency department was higher in patients with GIAI (81%) and SAI (70%) than in patients with PAI (58%), P < .0001 (Table 2).

Predictors of adverse outcomes

Patient unawareness of correct diagnosis.

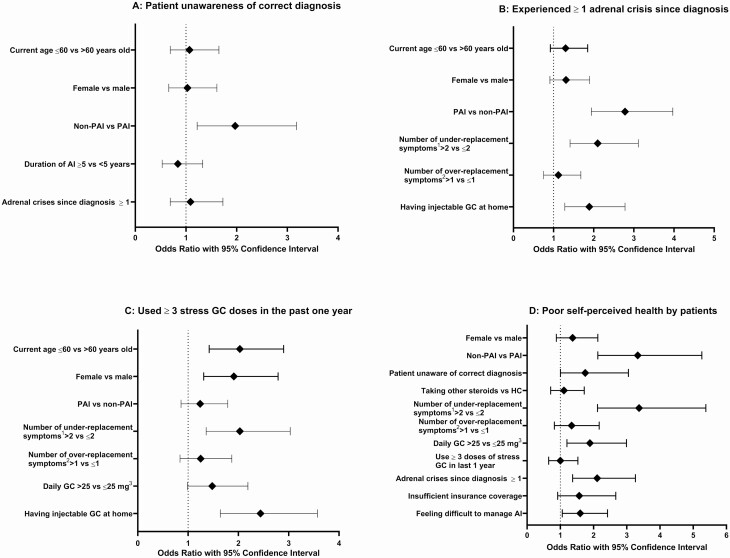

Patients with SAI and GIAI were more likely to report a wrong AI subtype, or not knowing the subtype than patients with PAI (adjusted OR 1.97, 95% CI 1.2-3.2); age, sex, duration of disease, and history of adrenal crises were not associated with knowledge of AI subtype (Fig.2A and Table 3).

Figure 2.

Multivariate analysis of predictors of adverse outcomes. (A) Predictors of patient unawareness of correct diagnosis. (B) Predictors of more than three stress GC usages in past one year. (C) Predictors of more than one adrenal crisis since diagnosis. (D) Predictors of poor self-perceived health by patients. Abbreviations: AI, adrenal insufficiency; GC, glucocorticoid; IM, intramuscular; PAI, primary adrenal insufficiency; Non-PAI, secondary adrenal insufficiency and glucocorticoid-induced adrenal insufficiency; HC, hydrocortisone.1Under-replacement symptoms included any of the following: fatigue, skin darkening, weight loss, decreased appetite, salt-craving, fainting, diarrhea, hypoglycemia, hypotension, muscle weakness or cramping, confusion, joint pain.2Over-replacement symptoms included any of the following: hypertension, hyperglycemia, irritability, insomnia, leg swelling, weight gain.3Daily glucocorticoid dose expressed as milligrams of hydrocortisone equivalents.

Table 3.

Predictors of adverse outcomes

| Predictors | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Outcome 1: Patient unawareness of correct diagnosis | ||

| Current age ≤60 vs >60 years old | OR 1.02 (95% CI 0.69-1.51) | OR 1.07 (95% CI 0.69-1.65) |

| Female vs male | OR 1.06 (95% CI 0.70-1.60) | OR 1.03 (95% CI 0.66-1.61) |

| Non-PAI vs PAI | OR 2.22 (95% CI 1.45-3.45) | OR 1.97 (95% CI 1.22-3.18) |

| Duration of AI ≥5 vs <5 years | OR 0.74 (95% CI 0.49-1.11) | OR 0.84 (95% CI 0.53-1.33) |

| Adrenal crises since diagnosis ≥ 1 | OR 0.82 (95% CI 0.54 -1.23) | OR 1.09 (95% CI 0.69-1.73) |

| Outcome 2: Experienced ≥ 1 adrenal crisis since diagnosis | ||

| Current age ≤60 vs >60 years old | OR 1.48 (95% CI 1.09-2.01) | OR 1.30 (95% CI 0.92-1.85) |

| Female vs male | OR 1.47 (95% CI 1.07-2.02) | OR 1.31 (95% CI 0.91-1.90) |

| PAI vs non-PAI | OR 2.74 (95% CI 2.00-3.75) | OR 2.78 (95% CI 1.94-3.97) |

| Number of under-replacement symptomsa >2 vs ≤2 | OR 1.92 (95% CI 1.39-2.66) | OR 2.10 (95% CI 1.41-3.11) |

| Number of over-replacement symptomsb >1 vs ≤1 | OR 1.51 (95% CI 1.10-2.10) | OR 1.12 (95% CI 0.75-1.68) |

| Daily GC >25 vs ≤25 mgc | OR 1.31 (95% CI 0.93-1.83) | Not included |

| Having injectable GC at home | OR 2.50 (95% CI 1.75-3.45) | OR 1.89 (95% CI 1.28-2.78) |

| Outcome 3: Use ≥ 3 GC stress doses in the past 1 year | ||

| Current age ≤60 vs >60 years old | OR 2.26 (95% CI 1.66-3.07) | OR 2.03 (95% CI 1.42-2.90) |

| Female vs male | OR 2.41 (95% CI 1.75-3.33) | OR 1.91 (95% CI 1.31-2.79) |

| PAI vs non-PAI | OR 1.42 (95% CI 1.04-1.92) | OR 1.24 (95% CI 0.86-1.79) |

| Number of under-replacement symptomsa >2 vs ≤2 | OR 2.35 (95% CI 1.70-3.26) | OR 2.03 (95% CI 1.36-3.03) |

| Number of over-replacement symptomsb >1 vs ≤1 | OR 2.01 (95% CI 1.45-2.79) | OR 1.25 (95% CI 0.84-1.87) |

| Daily GC >25 vs ≤25 mgc | OR 1.47 (95% CI 1.04-2.06) | OR 1.48 (95% CI 0.99 -2.19) |

| Having injectable GC at home | OR 2.70 (95% CI 1.92-3.85) | OR 2.44 (95% CI 1.64-3.57) |

| Outcome 4: Poor self-perceived health by patients | ||

| Current age ≤60 vs >60 years old | OR 1.08 (95% CI 0.79-1.48) | Not included |

| Female vs male | OR 2.01 (95% CI 1.43-2.82) | OR 1.37 (95% CI 0.88-2.13) |

| Non-PAI vs PAI | OR 3.03 (95% CI 2.13-4.17) | OR 3.33 (95% CI 2.13-5.26) |

| Patient unaware of correct diagnosis | OR 2.36 (95% CI 1.17-2.24) | OR 1.75 (95% CI 1.003-3.05) |

| Taking other glucocorticoids vs HC | OR 1.43 (95% CI 1.04-2.00) | OR 1.11 (95% CI 0.71-1.72) |

| Number of under-replacement symptomsa >2 vs ≤2 | OR 5.28 (95% CI 3.69-7.54) | OR 3.37 (95% CI 2.12-5.38) |

| Number of over-replacement symptomsb >1 vs ≤1 | OR 2.71 (95% CI 1.91-3.84) | OR 1.34 (95% CI 0.82-2.17) |

| Daily GC >25 vs ≤25 mgc | OR 1.77 (95% CI 1.25-2.49) | OR 1.89 (95% CI 1.20-2.99) |

| Use ≥ 3 doses of stress GC in last 1 year | OR 1.77 (95% CI 1.29-2.43) | OR 1.00 (95% CI 0.65-1.53) |

| Adrenal crises since diagnosis ≥ 1 | OR 1.75 (95% CI 1.27-2.42) | OR 2.11 (95% CI 1.37-3.26) |

| Insufficient insurance coverage | OR 2.58 (95% CI 1.69-3.95) | OR 1.57 (95% CI 0.92-2.67) |

| Feeling difficult to manage AI | OR 2.18 (95% CI 1.57-3.02) | OR 1.60 (95% CI 1.06-2.42) |

Abbreviations: AI, adrenal insufficiency; GC, glucocorticoid; HC, hydrocortisone; IM, intramuscular; PAI: primary adrenal insufficiency; non-PAI, secondary adrenal insufficiency and glucocorticoid-induced adrenal insufficiency; HC, hydrocortisone.

a Under-replacement symptoms included any of the following: fatigue, skin darkening, weight loss, decreased appetite, salt-craving, fainting, diarrhea, hypoglycemia, hypotension, muscle weakness or cramping, confusion, joint pain.

b Over-replacement symptoms included any of the following: hypertension, hyperglycemia, irritability, insomnia, leg swelling, weight gain.

c Daily glucocorticoid dose expressed as milligrams of hydrocortisone equivalents.

Adrenal crisis.

Patients with PAI (vs other subtypes) (adjusted OR 2.8, 95% CI 1.9-4.0), if they reported a higher number of symptoms suggestive of glucocorticoid under-replacement (adjusted OR 2.1, 95% CI 1.4-3.1), and if they had injectable glucocorticoid at home (adjusted OR 1.9, 95% CI 1.3-2.8) were associated with higher occurrence of adrenal crisis; age and sex were not significant contributors (Fig. 2B and Table 3).

Use of stress dose glucocorticoids.

Patients were more likely to use 3 or more stress glucocorticoid doses if younger (adjusted OR 2.0, 95% CI 1.4-2.9), female (adjusted OR 1.9, 95% CI 1.3-2.8), reported a higher number of glucocorticoid under-replacement symptoms (adjusted OR 2.0, 95% CI 1.4-3.0), and if they had injectable glucocorticoid at home (adjusted OR 2.4, 95% CI 1.6-3.6) (Fig. 2C and Table 3).

Self-perceived health

Factors that independently associated with poor self-perceived health included a diagnosis of SAI and GIAI (vs PAI) (adjusted OR 3.3, 95% CI 2.1-5.3), unawareness of correct diagnosis (adjusted OR 1.8, 95% CI 1.003-3.1), higher number of symptoms suggestive of glucocorticoid under-replacement (adjusted OR 3.4, 95% CI 2.1-5.4), supraphysiologic glucocorticoid dosing (adjusted OR 1.9, 95% CI 1.2-3.0), occurrence of adrenal crisis since diagnosis (adjusted OR 2.1, 95% CI 1.4-3.3), and reported difficulty with self-management (adjusted OR 1.6, 95% CI 1.1-2.4) (Fig. 2D and Table 3).

Discussion

In this study, we aimed to characterize self-reported health and determinants of adverse outcomes in patients with AI in the United States, with a specific objective of understanding how different subtypes of AI could influence these outcomes. Notably, our findings underscore the vulnerability of PAI patients to adrenal crises, as well as delays in making the correct diagnosis and providing prompt care for these patients during crises. We also identified a number of important patient- and clinician-related risk factors that could be targeted and modified to improve future patient outcomes.

We found that making the diagnosis of AI was challenging, with 64% of patients evaluated by multiple clinicians for symptoms, with a median duration of symptoms prior to diagnosis of 1 year. Potential explanations for delayed diagnosis include nonspecific symptoms of AI, delayed evaluation by subspecialists, or possibly the lack of available diagnostic testing in a nonendocrine practice. Similar results were reported by a Norwegian study with more than 40% of patients with PAI diagnosed after 6 months of symptoms (17), and a German study with more than 50% of patients with PAI and SAI diagnosed 6 months after onset of symptoms (18). Surprisingly, we found that despite having a clear clinical and biochemical diagnosis documented in the medical record, 8% of patients still reported not knowing their AI subtype, and another 10% reported the wrong subtype. This reflects a knowledge gap in patients’ understanding of their disease, possibly due to lack of detailed education by the medical team. We further found that this patient unawareness of correct diagnosis was associated with poor self-perceived health, further underlining the importance of proper education.

The present study is the first study that comprehensively addresses differences in presentation, management, and patient outcomes between 3 different subtypes of AI. When compared with patients with SAI and GIAI, patients with PAI reported a more severe presentation at the time of diagnosis, with an earlier onset and a longer duration of disease. This is probably because autoimmune adrenalitis as the most common etiology of PAI (70-90% of cases), occurs at a younger age (2, 19-21). Despite being on a higher daily glucocorticoid dosage, patients with PAI used stress glucocorticoid doses more frequently and still experienced a higher number of adrenal crises. Remarkably, nearly 60% of PAI patients in our study reported a history of adrenal crisis since diagnosis, nearly double the frequency in patients with SAI and GIAI. This stark statistic underscores the vulnerability to adrenal crisis in patients with PAI, possibly due to concomitant mineralocorticoid deficiency, and the need for thorough patient and clinician education on how adrenal crises could be prevented and managed. Previously, Hahner et al. reported that circa 42% of patients with PAI and 35% of patients with SAI experienced at least 1 adrenal crisis (12). Higher frequency of adrenal crises in our study could be explained by a sicker referral population or longer duration of AI in our cohort allowing more time to record adrenal crises, or possibly geographic/national differences. Surprisingly, despite experiencing more adrenal crises, using more stress glucocorticoid doses, and therefore a higher disease burdern, patients with PAI reported a better perception of health status. This could be multifactorial: a higher degree of knowledge of their disease, higher compliance with wearing medical alert gear, higher availability of injectable glucocorticoid, a higher comfort level managing AI, and a better support system. Moreover, in patients with SAI, the concomitant pituitary deficiencies may also contribute to disease burden and a worse perception of health status (22-24).

The incidence rate of adrenal crisis in our cohort was 24/100 patient-years, higher than 4.4 to 17/100 patient-years reported in other studies (12, 25-27). The higher incidence could be due to more severe AI in our US cohort, variable definitions of “adrenal crisis” by patients, and recall bias. However, the finding that 44% of patients reported having at least 1 adrenal crisis since the initial diagnosis of AI was similar to another study (12). After adjustment for potential confounders, we found that patients with PAI (vs other subtypes) were more likely to develop adrenal crisis, as well as reporting a higher number of symptoms suggestive of glucocorticoid under-replacement. In addition, we found that patients with available injectable glucocorticoid at home were more likely to report adrenal crisis, possibly due to increased vulnerability and underlying concern with the history of adrenal crises. We have also identified a gap in the management of adrenal crisis in the emergency department. Only 35% of patients reported to receive timely parenteral glucocorticoid when presenting to the emergency department, another 45% received treatment after explaining their AI plan, while the rest (20%) experienced delay in treatment. One other study in Europe reported that only 54% of patients with AI received treatment within 30 minutes after presentation of adrenal crises (5). While our study could not quantify the exact duration of delay, our findings suggest that the majority of patients did not receive sufficient attention when presenting with adrenal crises, highlighting the need for higher familiarity with AI among emergency clinicians and first responders.

There are several other novel findings from our study. First, we found that insufficient insurance coverage was associated with poor self-perceived health, a unique attribute of the US health system. Overall, 16% of patients reported insufficient coverage from their medical insurance while 44% attributed AI as the cause of their financial burden, causing inability to work in 10% patients. Two previous studies based on the US national payer database showed that patients with AI had significant metabolic or psychiatric comorbidities and hospital admissions, and therefore had substantially higher annual healthcare burdens than controls (7, 28). Our findings and previous reports suggest that efforts need to be targeted to reduce financial burden from AI. Secondly, we found that a large proportion (71%) of patients expressed strong interest in participating in a disease specific patient group. Currently, several online forums for Addison disease are described in the literature, which appeared to help patients gain knowledge and emotional support from their peers (29-31). This experience-based knowledge sharing and patient-centered advice could become a very important information source, complementary to the care provided by medical professionals. Thirdly, we found that 38% of patients reported the usage of conservative nonpharmacologic modalities including acupuncture, chiropractor, homeopathic or naturopathic therapy, dietary modification therapy, and reflexology as adjunct treatment of AI. While not previously reported in AI, conservative nonpharmacologic treatment was utilized in other medical conditions such chronic somatic pain, visceral pain, and cancer-related depression with some benefit in symptomatic improvement (32-34). However, the quality of evidence in these studies was low, and future prospective studies are needed to illustrate the effectiveness of such treatments in patients with AI. Fourthly, we found the difference in preferred glucocorticoid formulation between our centers and data from the European Adrenal Insufficiency Registry (35). Notably, 23% of patients with PAI and SAI were on prednisone or prednisolone and 1% were on dexamethasone, higher than 5.1% and 0.1% reported in Europe, reflecting potential differences in approaches to management of AI (35). Such differences in management with possible implications on patient outcomes warrant further comparisons in future studies. Lastly, although more than 80% of the patients reported support from family and friends during adrenal crisis, as well as good financial support from insurance company, the proportion was lower in patients with SAI and GIAI, suggesting that further improvements are needed in all subtypes, especially in patients with SAI and GIAI.

The present study has several strengths and limitations. This was a large multisite survey study from 2 tertiary care US hospital networks. We used a comprehensive patient-centered survey that assessed not only disease burden, self-management, but also patient’s education and comprehension, which has not been reported in detail previously. We acknowledge several potential limitations, including selection, referral, and recall biases. Patients included in the study were evaluated in 2 tertiary medical centers in the United States and may have had more severe symptoms, but also were more likely to receive subspecialized endocrine care. Therefore, the results of this study may not be generalizable to populations outside our tertiary care networks, or outside the United States, or to non-Caucasian populations (as 93% of our study participants were Caucasian). However, despite this potential selection bias, our findings highlight the gaps in education and management of patients with AI. This racial and ethnic bias may reflect in part the demographics of the respective academic medical centers. Nonresponse bias is inevitable in survey research. The overall survey response rate was relatively low at 35% and likely reflected our approaches to recruiting participants using institutional research and ethics standards of contact; whether the rate of responses could have resulted in reporting bias is not clear; however, there were no major differences between responders and nonresponders. Recall bias was also likely for survey questions relating to symptoms at the time of initial diagnosis. The definition of adrenal crisis in the survey relied on patient’s understanding and may not be identical to what other studies referred to. Lastly, the cut-off we used to define “supraphysiologic glucocorticoid dosage” was 25 mg of HC equivalence is arbitrary, based on the Endocrine Society guidelines that define physiological dose between 15 and 25 mg (15).

Clinical implications

We identified patient-, clinician-, and society-related factors that contributed to self-reported health outcomes in patients with AI (Table 4). While certain patient-related factors are nonmodifiable (age, sex, duration, or subtype of AI), many can be addressed with the goal to improve outcomes. These include understanding medical diagnosis, adherence to glucocorticoid replacement regimen, recognizing symptoms of glucocorticoid under- and over-replacement, knowing indications for stress glucocorticoids, having injectable glucocorticoids available, and wearing medical alert gears. We have also identified several clinician-related factors that could be addressed with more training provided for emergency and internal medicine clinicians. In addition, more effort should be invested into detailed hands-on education sessions in the endocrine/adrenal clinic. Finally, we identified social support as important, including support from family members, friends, insurance company, and patient groups. Future studies should address a prospective longitudinal assessment of disease burden and intervention with detailed education.

Table 4.

Current gaps in care of patients with adrenal insufficiency

| Patient | Clinician | Societal support |

|---|---|---|

|

Diagnosis

1. Understanding diagnosis, including type of adrenal insufficiency, so that patients can relay this information as needed for medical care and social support 2. For patients with PAI, special attention is needed for understanding added implications of mineralocorticoid deficits Chronic management of AI 3. Consistency with taking GC regimen 4. Understanding symptoms of under- and over-replacement of GC in an effort to effectively communicate dosing issues to the healthcare team 5. For patients with PAI, orthostatic blood pressure education may be beneficial to assess adequacy of mineralocorticoid replacement Prevention and treatment of adrenal crisis 6. Taking stress dose glucocorticoids when indicated (to avoid adrenal crisis) and avoiding stress dose GC when not indicated (to avoid complications of GC) 7. Consistency with wearing medical alert gear 8. Availability of home injectable GC and comfort with administration if needed |

Diagnosis

1. Since diagnosis of AI is frequently delayed, clinicians must be educated regarding the signs and symptoms of AI and the approach to diagnostic confirmation. 2. Testing for AI should occur immediately with expedited access to endocrine expertise if needed for diagnosis and treatment. Consultation can take the form of telemedicine or phone consultation as appropriate 3. The endocrine community has a responsibility to educate surrounding primary care and emergency room clinicians about diagnosing AI. 4. Clinicians must allocate sufficient time to explaining AI to patient and family Chronic management of AI 5. Every patient with AI would benefit from an adrenal action plan may serve as a written record of AI type, standard replacement, and replacement at times of illness 6. Appropriate GC replacement to avoid under- and over-replacement 7. For patients with PAI, appropriate mineralocorticoid replacement to maintain clinical euvolemia and electrolytes Prevention and treatment of adrenal crisis 8. Educate patients on importance of wearing medical alert gear and maintaining copy of adrenal action plan for cases of emergency 9. Review indications for stress dose GC at every visit and maintain an active prescription for injectable GC 10. Provide education for local emergency room staff regarding identification and prompt management of adrenal crisis. Specifically, all patients with AI should be given IV GC; patients with PAI (lacking mineralocorticoid activity) may additionally require aggressive volume expansion with IV fluid |

Diagnosis

1. Assure optimal insurance reimbursement for adrenal insufficiency diagnosis and care 2. Facilitate access to adrenal endocrinologists Chronic management of AI 3. Support person would benefit from education about AI to increase understanding of the condition 4. Multiple types of support networks (online and in-person) to serve varied roles, including opportunities for patient/family education, forums for group support, and access to open discussion with adrenal experts 5. Insurance coverage of crucial medical treatments including injectable GC Prevention and treatment of adrenal crisis 6. Support person should be taught to recognize symptoms of adrenal crisis 7. Support person should have access to adrenal action plan and receive education of administration of injectable GC |

Abbreviations: AI, adrenal insufficiency; IV, intravenous; PAI, primary adrenal insufficiency; GC, glucocorticoid.

In conclusion, patients with AI experience substantial disease burden and adverse outcomes, reflective of current gaps at the patient, clinician, and societal levels. While patients with PAI were treated with higher daily glucocorticoid dose were more likely to use stress doses of glucocorticoids and reported more adrenal crises, they were also more knowledgeable about their disease, were more comfortable managing it, received a higher level of support, and reported better self-perceived health. A multidimensional effort is needed for timely and accurate diagnosis, to identify patients with high risk of developing adverse outcomes, to ensure adequate patient education, and to offer sufficient support in patients with AI.

Acknowledgment

The authors are grateful to the patients who volunteered to participate in this study.

Financial Support: The study was supported by the Ventus Charitable Foundation (to A.V.) and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) USA under award K23DK121888 (to I.B). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the Ventus Charitable Foundation, or the National Institutes of Health USA.

Author Contributions: D.L. and N.G., contributed to data collection, data analysis, and data interpretation; did the literature search; co-wrote the manuscript. M.X., E.B., and T.A. contributed to data collection, and edited the manuscript. I.B. and A.V. edited the protocol; contributed to data collection, data analysis, and data interpretation; did the literature search; cowrote the manuscript, and supervised all steps of the conduct of the study.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AI

adrenal insufficiency

- CI

confidence interval

- GIAI

glucoc

- or

ticoid-induced adrenal insufficiency

- HC

hydrocortisone

- IQR

interquartile range

- OR

odds ratio

- PAI

primary adrenal insufficiency

- SAI

secondary adrenal insufficiency

Additional Information

Disclosure Summary: I.B. reports advisory board participation with Corcept, ClinCor, and HRA Pharma outside the submitted work. A.V. reports consulting/advisory participation and remuneration for Corcept, HRA Pharma, and CatalysPacific, all unrelated to the current work. The remainder of authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1. Bancos I, Hahner S, Tomlinson J, Arlt W. Diagnosis and management of adrenal insufficiency. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015;3(3):216-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chabre O, Goichot B, Zenaty D, Bertherat J. Group 1. Epidemiology of primary and secondary adrenal insufficiency: prevalence and incidence, acute adrenal insufficiency, long-term morbidity and mortality. Ann Endocrinol (Paris). 2017;78(6):490-494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Joseph RM, Hunter AL, Ray DW, Dixon WG. Systemic glucocorticoid therapy and adrenal insufficiency in adults: a systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016;46(1):133-141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hahner S, Loeffler M, Fassnacht M, et al. Impaired subjective health status in 256 patients with adrenal insufficiency on standard therapy based on cross-sectional analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(10):3912-3922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hahner S, Hemmelmann N, Quinkler M, Beuschlein F, Spinnler C, Allolio B. Timelines in the management of adrenal crisis – targets, limits and reality. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2015;82(4):497-502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Øksnes M, Bensing S, Hulting AL, et al. Quality of life in European patients with Addison’s disease: validity of the disease-specific questionnaire AddiQoL. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(2):568-576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gunnarsson C, Ryan MP, Marelli C, et al. Health care burden in patients with adrenal insufficiency. J Endocr Soc. 2017;1(5):512-523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bleicken B, Hahner S, Loeffler M, et al. Influence of hydrocortisone dosage scheme on health-related quality of life in patients with adrenal insufficiency. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2010;72(3):297-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Løvås K, Loge JH, Husebye ES. Subjective health status in Norwegian patients with Addison’s disease. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2002;56(5):581-588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Erichsen MM, Løvås K, Skinningsrud B, et al. Clinical, immunological, and genetic features of autoimmune primary adrenal insufficiency: observations from a Norwegian registry. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(12):4882-4890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hahner S, Spinnler C, Fassnacht M, et al. High incidence of adrenal crisis in educated patients with chronic adrenal insufficiency: a prospective study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(2):407-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hahner S, Loeffler M, Bleicken B, et al. Epidemiology of adrenal crisis in chronic adrenal insufficiency: the need for new prevention strategies. Eur J Endocrinol. 2010;162(3):597-602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Punthakee Z, Legault L, Polychronakos C Prednisolone in the treatment of adrenal insufficiency: a re-evaluation of relative potency. J Pediatr. 2003;143(3):402-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bornstein SR, Allolio B, Arlt W, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of primary adrenal insufficiency: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(2):364-389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dingfeng L, Natalia G, Emma B, et al. Data from: determinants of self-reported health outcomes in adrenal insufficiency: a multi-site survey study. 2020.

- 17. Erichsen MM, Løvås K, Fougner KJ, et al. Normal overall mortality rate in Addison’s disease, but young patients are at risk of premature death. Eur J Endocrinol. 2009;160(2):233-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bleicken B, Hahner S, Ventz M, Quinkler M. Delayed diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency is common: a cross-sectional study in 216 patients. Am J Med Sci. 2010;339(6):525-531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zelissen PM, Bast EJ, Croughs RJ. Associated autoimmunity in Addison’s disease. J Autoimmun. 1995;8(1):121-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kasperlik-Zaluska AA, Migdalska B, Czarnocka B, Drac-Kaniewska J, Niegowska E, Czech W. Association of Addison’s disease with autoimmune disorders–a long-term observation of 180 patients. Postgrad Med J. 1991;67(793):984-987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Moreira AC, Martinez R, Castro M, Elias LL. Adrenocortical dysfunction in paracoccidioidomycosis: comparison between plasma beta-lipotrophin/adrenocorticotrophin levels and adrenocortical tests. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1992;36(6):545-551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Andela CD, Scharloo M, Pereira AM, Kaptein AA, Biermasz NR. Quality of life (QoL) impairments in patients with a pituitary adenoma: a systematic review of QoL studies. Pituitary. 2015;18(5):752-776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. van Aken MO, Pereira AM, Biermasz NR, et al. Quality of life in patients after long-term biochemical cure of Cushing’s disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(6):3279-3286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wagenmakers MA, Netea-Maier RT, Prins JB, Dekkers T, den Heijer M, Hermus AR. Impaired quality of life in patients in long-term remission of Cushing’s syndrome of both adrenal and pituitary origin: a remaining effect of long-standing hypercortisolism? Eur J Endocrinol. 2012;167(5):687-695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Smans LC, Van der Valk ES, Hermus AR, Zelissen PM. Incidence of adrenal crisis in patients with adrenal insufficiency. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2016;84(1):17-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hahner S. Acute adrenal crisis and mortality in adrenal insufficiency: Still a concern in 2018! Ann Endocrinol (Paris). 2018;79(3):164-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Meyer G, Koch M, Herrmann E, Bojunga J, Badenhoop K. Longitudinal AddiQoL scores may identify higher risk for adrenal crises in Addison’s disease. Endocrine. 2018;60(2):355-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Stewart PM, Biller BM, Marelli C, Gunnarsson C, Ryan MP, Johannsson G. Exploring inpatient hospitalizations and morbidity in patients with adrenal insufficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(12):4843-4850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kauw D, Repping-Wuts H, Noordzij A, Stikkelbroeck N, Hermus A, Faber M. The contribution of online peer-to-peer communication among patients with adrenal disease to patient-centered care. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(2):e54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Repping-Wuts HJ, Stikkelbroeck NM, Noordzij A, Kerstens M, Hermus AR. A glucocorticoid education group meeting: an effective strategy for improving self-management to prevent adrenal crisis. Eur J Endocrinol. 2013;169(1):17-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. White KG, Willson N, Sharman P, Smith V Addison’s forum helps to support and engage patients. BMJ. 2016;354:i4998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Coutiño-Escamilla L, Piña-Pozas M, Tobías Garces A, Gamboa-Loira B, López-Carrillo L. Non-pharmacological therapies for depressive symptoms in breast cancer patients: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Breast. 2019;44:135-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Franco JV, Turk T, Jung JH, et al. Non-pharmacological interventions for treating chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;5:CD012551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Salvioli S, Guidi M, Marcotulli G. The effectiveness of conservative, non-pharmacological treatment, of plantar heel pain: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Foot (Edinb). 2017;33:57-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Murray RD, Ekman B, Uddin S, Marelli C, Quinkler M, Zelissen PM; the EU-AIR Investigators . Management of glucocorticoid replacement in adrenal insufficiency shows notable heterogeneity - data from the EU-AIR. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2017;86(3):340-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.