Abstract

Context

Pseudohypoparathyroidism type 1A (PHP1A) and pseudopseudohypoparathyroidism (PPHP) are caused by inactivating mutations in the exons of GNAS that encode the alpha-subunit of the stimulatory G protein (Gsα). In some cases abnormal methylation of exon A/B of GNAS, a hallmark of PHP1B, has been reported.

Objective

To identify the underlying genetic basis for PHP1A/PPHP in patients in whom molecular defects were not detected by GNAS sequencing and microarray-based analysis of copy number variations.

Methods

Whole genome sequencing (WGS) and pyrosequencing of differentially methylated regions (DMRs) of GNAS using genomic deoxyribonucleic acid from affected patients.

Results

We identified 2 novel heterozygous GNAS deletions: a 6.4 kb deletion that includes exon 2 of GNAS in the first proband that was associated with normal methylation (57%) of exon A/B DMR, and a 1438 bp deletion in a second PHP1A patient that encompasses the promoter region and 5′ untranslated region of Gsα transcripts, which was inherited from his mother with PPHP. This deletion was associated with reduced methylation (32%) of exon A/B DMR.

Conclusions

WGS can detect exonic and intronic mutations, including deletions that are too small to be identified by microarray analysis, and therefore is more sensitive than other techniques for molecular analysis of PHP1A/PPHP. One of the deletions we identified led to reduced methylation of exon A/B DMR, further refining a region needed for normal imprinting of this DMR. We propose that deletion of this region can explain why some PHP1A patients have reduced of methylation of the exon A/B DMR.

Keywords: GNAS, GNAS deletion, pseudohypoparathyroidism, PHP1A

Pseudohypoparathyroidism type 1A (PHP1A) is a developmental disorder characterized by resistance to multiple hormones and a constellation of somatic defects termed Albright hereditary osteodystrophy (AHO; OMIM 103580), which includes short stature, brachydactyly, and heterotopic ossification. PHP1A results from heterozygous mutations within exons 1-13 of the maternal allele of GNAS, including both point mutations and rare structural rearrangements, that reduce the expression or function of Gsα, the alpha-subunit of the heterotrimeric stimulatory G protein that couples heptahelical receptors to activation of adenylyl cyclase (1, 2). By contrast, subjects with identical mutations on paternally inherited GNAS alleles manifest AHO but have normal hormone responsiveness, a condition termed pseudopseudohypoparathyroidism (PPHP) (3, 4). The variable expression of hormone resistance in different tissues and patients with GNAS mutations has been attributed to genomic imprinting of GNAS, a highly complex genetic locus on chromosome 20q13.3 (5-9) that contains multiple alternative first exons which encode novel proteins as well as exons that generate a regulatory antisense transcript (1, 2, 10-12). Utilization of these alternative first exons to generate additional transcripts is regulated by differentially methylated regions (DMRs) such that the extra-large variant of Gsα (XLαs), an amino terminus truncated form of Gsα utilizing exon A/B, and the antisense transcript (AS) are transcribed from the paternal GNAS allele while neuroendocrine secretory protein 55 (NESP55) is transcribed from the maternal allele (1, 2, 10-12). Although exon 1 does not have an associated DMR, transcription is subject to tissue-specific imprinting. Gsα is expressed from both parental alleles in most tissues but in some cells such as proximal renal tubular epithelium, pituitary somatotropes, gonads, thyroid epithelial cells, and regions of the central nervous system, transcription of Gsα is predominately from the maternal GNAS allele (13-19). Thus, tissue-specific paternal imprinting of Gsα accounts for the distinctive pattern of hormone resistance, obesity, and neurocognitive dysfunction in patients with PHP1A who carry maternal GNAS mutations (8, 9, 20, 21).

Epigenetic defects that reduce expression of Gsα from the maternal GNAS allele account for the development of parathyroid hormone (PTH) resistance in patients with pseudohypoparathyroidism type 1B (PHP1B) (10, 22). Subjects with PHP1B may also manifest mild thyrotropin (TSH) resistance, early-onset obesity, and brachydactyly, but typically lack the major features of AHO, especially heterotopic ossification (23-28). Most PHP1B cases are sporadic, and some can be explained by paternal uniparental disomy of chromosome 20q, which leads to global defects in methylation at all of GNAS DMRs (29). By contrast, the epigenetic defect in most cases of familial PHP1B is limited to loss of methylation at the exon A/B DMR, which is associated with heterozygous deletions within the maternal STX16 allele (30). A minority of familial PHP1B patients have global methylation defects at DMRs associated with the exons of NESP55, XLαs/AS, and A/B (ie, high–low–low methylation pattern) due to heterozygous deletions affecting the first exon of NESP55 and/or AS exons on the maternal GNAS allele (28, 31-33).

Since the initial identification in 1990 of heterozygous inactivating protein-coding mutations in Gsα in patients with PHP1A and PPHP (5-7), more than 200 pathogenic point mutations and small coding insertions/deletions (indels) have been described (reviewed in (34)). The majority of these mutations are nonsense or truncating mutations (loss of function), and intragenic deletions and rearrangements that affect GNAS exons are rarely reported as causes of PHP1A by Sanger sequencing and whole exome sequence (WES) analysis. Here we describe the application of whole genome sequencing (WGS) to identify the molecular basis for PHP1A/PPHP in 2 kindreds. We identified 2 novel deletions, including 1 with a breakpoint near exon A/B that also led to reduced methylation at exon A/B DMR.

Subjects and Methods

Patients

Patient 1 presented at age 21.4 years to the Medical Genetics Clinic at Spectrum Health for diagnostic evaluation of early-onset obesity, congenital hypothyroidism, brachydactyly (short first and fourth metatarsals and short fourth and fifth metacarpals), multiple subcutaneous ossifications, and mild learning difficulties. He was the second child of nonconsanguineous parents. He was born at 42 weeks’ gestation via C-section due to breech presentation. He required some respiratory resuscitation at birth but was discharged home at 3 days of life. The medical history was notable for postnatal growth failure, bilateral carpal tunnel syndrome that was treated by surgery, and right-sided hearing loss secondary to a cholesteatoma that was removed at age 8 years. At the time of evaluation his height was 153.3 cm (Z = −3.26) and weight was 81 kg (82% percentile), with body mass index of 34.1 (Z = 2.24). He has Horner syndrome and a history of asthma. His most recent laboratory findings while taking levothyroxine showed a normal TSH level of 0.29 µIU/mL (reference range: 0.27-4.2), a normal calcium level of 9.5 mg/dL (reference range: 8.6-10.3 mg/dL), and a significantly elevated level of intact PTH of 199 pg/mL (reference range: 15-65). He has an older sister (170 cm) and a younger brother (180 cm) who both have learning disorders but no endocrine defects or features of AHO. Father (191 cm) and mother (155 cm) were both normal. Sanger sequencing of GNAS exons 1-13 (Johns Hopkins DNA Diagnostic Laboratory) was normal. Genetic analysis using the high-resolution GGXChip + SNP v1.0 4-plex comparative genome hybridization (CGH) array revealed the patient to be 46XY with benign deletions noted at Xp22.31 (78.46 Kb), 3p12.3-p12.1 (7.61 Mb), and 5q14.3 (4.35 Mb). Methylation analysis of exon A/B DMR (Johns Hopkins DNA Diagnostic Laboratory) revealed normal methylation at 45% (normal >43%).

Patient 2 presented at age 20 months to the Endocrine Clinic at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia for evaluation and management of PHP1A. He was the first pregnancy to a 32-year-old mother and 32-year-old father; pregnancy was facilitated by in vitro fertilization owing to poor sperm motility. The mother developed gestational diabetes, which was treated by diet, and took enoxaparin for thrombosis. The patient was delivered at full term by C-section with a birth weight of 2.72 kg and length of 47 cm. The newborn screen showed slightly elevated TSH with normal total serum T4 and he was subsequently begun on daily levothyroxine. Soon after birth he was noted to have multiple subcutaneous ossifications (right leg, right chest, and head, bottom of left foot). Postnatally, he grew along the 15th percentile for length and the 98th percentile for weight, with a body mass index of 21.7 kg/m2 (>99.98% percentile; Z = 2.72 standard deviation score), until age 5.5 years, when his weight was Z = 2.8 standard deviation score and height at the 50% to 60% percentile. At age 5.5 years his physical examination was significant for subcutaneous ossifications but no brachydactyly; he had some speech delay and has received school-based enrichment and therapy. His serum levels of calcium, phosphorus, and intact PTH were normal until age 2.5 years, when his intact PTH increased to 218 pg/mL (reference range: 15-65) with corresponding serum levels of calcium of 8.8 mg/dL and phosphorus of 7.6 mg/dL. He was subsequently treated with calcitriol and calcium carbonate. He began treatment with growth hormone at age 3 years after clonidine/arginine-stimulated growth hormone testing showed a subnormal peak growth hormone value of 3.8 ng/mL. Molecular analyses were performed at the Johns Hopkins DNA Diagnostic Laboratory, where sequence analysis of GNAS exons 1-13 was normal and methylation analysis of the GNAS exon A/B DMR was reduced at 34% (normal >43%). A single nucleotide polymorphism microarray was negative for causative copy number variations. His bone age has been normal. Research whole exome sequencing had failed to disclose a causative mutation (data not shown).

The proband’s mother had been diagnosed with AHO/PPHP at age 17 years, and was noted to have brachydactyly at age 7 to 8 years. She has multiple subcutaneous ossifications and intermittently mildly elevated TSH, for which she had taken levothyroxine. Her serum levels of PTH, calcium, and phosphorus were normal. She had menarche at age 12 years and has regular menses. The father and a 13-month-old sister are healthy.

These studies were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the participating hospitals and all subjects provided written informed consent/assent for participation in the study.

CpG methylation analysis

CpG methylation analysis was determined using genomic deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) that had been purified from peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Methylation status of CpG dinucleotides was determined by PCR amplification of bisulfite-modified, RNase-treated genomic DNA, followed by pyrosequencing using assays designed by EpigenDx (Worcester, MA). Nucleotides sequences in GNAS (20q13.32) that were analyzed were in the DMRs for NESP55 (ADS471; 20(GRCh37):g.57415807-57415853), XLαs (ADS470; 20(GRCh37):g.57429235-57429362), and exon A/B (ADS464; 20(GRCh37):g.57464773-57464927). We also used assay ADS1410 to analyze methylation of the DMR of the imprinted gene NNAT encoding neuronatan on chromosome at 20q11.23 (20(GRCh37):g.36149607-36152092). Experimental conditions are available upon request. Bisulfite pyrosequencing is a sequencing-by-synthesis method used to quantitatively determine the methylation of individual CG cytosines from PCR amplicons of a region up to 115 bases in length. The procedure relies on prior bisulfite conversion of all potentially methylated CpG cytosines to either cytosine (methylated) or thymine (unmethylated) and involves the stepwise incorporation of deoxynucleotide triphosphates into the growing strand of nascent DNA. The incorporation of these deoxyribonucleotides (dNTPs) results in the proportional release of pyrophosphate, which is then converted to adenosine triphosphate. The procedure is quantitative, and is based upon adenosine triphosphate facilitating a catalytic reaction by firefly luciferase in which luciferin is converted to oxyluciferin, and the amount of light released is proportional to the number of nucleotides incorporated. Methylation is expressed as the percentage of cytosines within the CpG sequences that are methylated.

Whole genome sequencing and bioinformatic analysis

We performed WGS on the 2 unrelated patients with PHP1A using Illumina HiSeq X Ten with paired-end 150 bp reads. Libraries were generated from genomic DNA using the Illumina TruSeq DNA PCR-Free Library Prep Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA). All the raw reads were aligned to the reference human genome using the Burrows–Wheeler Aligner (BWA-Mem) (35) and single-nucleotide variants and small indels were captured using the Genome Analysis Tool Kit (36). ANNOVAR (37) and SnpEff (38) were subsequently used to functionally annotate the variants. BAM files generated by the Genome Analysis Tool Kit were fed to multiple short-read structural variant callers, including BreakDancer (39), Manta (40), Wham (41), and CNVnator (42), to capture structural variations (SVs) with default parameters. Similarly, the split and discordant reads files were generated by SpeedSeq (43) and were provided as inputs to Lumpy (44), another SV calling program.

Statistics

Pyrosequencing results are presented as the mean ± SD, and comparisons between groups were analyzed by analysis of variance using Tukey–Kramer multiple comparison tests using GraphPad InStat 3 (San Diego, CA).

Results

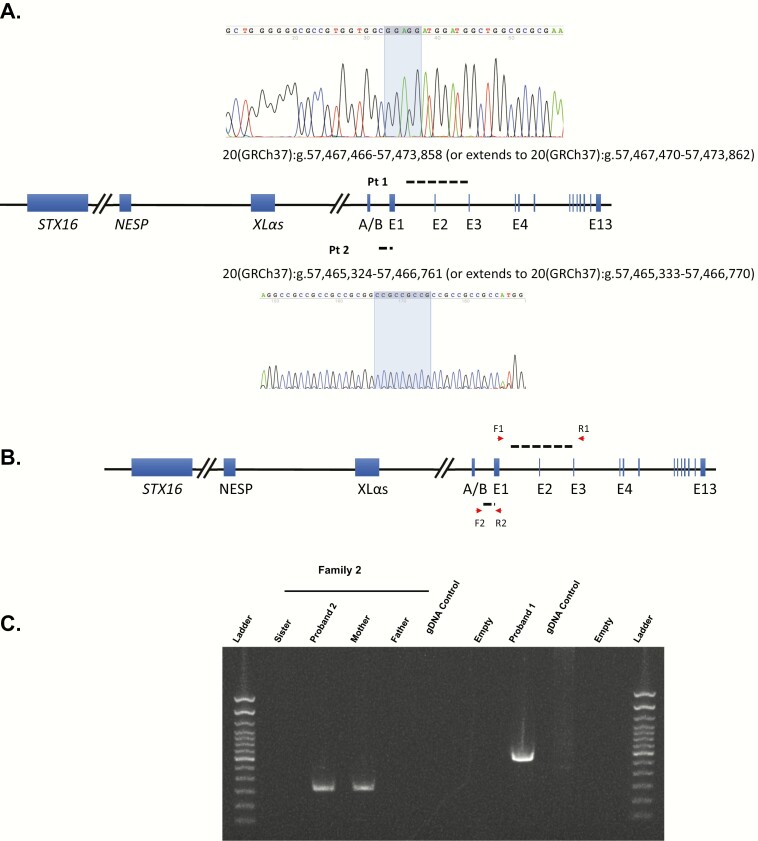

The average WGS coverage depth for patient 1 and patient 2 was 32- and 33-fold, respectively. Analyses of single-nucleotide variants and small indels did not reveal any rare disease-causing variants in GNAS exons 1-13 and exon–intron junctions in the 2 patients, which confirmed the previously uninformative results by Sanger sequencing and WES. Similarly, prior comparative genome hybridization had failed to identify a pathogenic deletion. We then focused on structural variation analysis at 20q13.3, where GNAS is located (7). For patient 1, a novel heterozygous 6.4-kb intragenic deletion that includes exon 2 of GNAS was captured by Manta and Lumpy with the support of BreakDancer and CNVnator. With Sanger sequencing and subsequent bioinformatic analyses to infer the underlying molecular mechanism of deletion formation, we were able to map the 2 breakpoints within 20(GRCh37):g.57,467,466-57,467,470 (20:58,892,411-58,892,415, hg38 version) and 20(GRCh37):g.57,473,859-57,473,863 (20:58,898,804-58,898,808, hg38 version) that are associated with a direct 5 bp microhomology (GGAGG; Fig. 1A). Searching low copy repeats (LCRs), long interspersed nuclear elements, and short interspersed nuclear elements/Alus flanking both breakpoints of the deletion by using RepeatMasker (http://www.repeatmasker.org/cgi-bin/WEBRepeatMasker) did not reveal any pairs of elements consisting of both breakpoints. Taken together these results suggest that the deletion may have arisen by a template switching replicative mechanism such as fork stalling and template switching (FoSTeS) or microhomology-mediated break-induced replication (MMBIR) (45, 46). DNA was not available from other members of this proband’s family.

Figure 1.

Intragenic GNAS deletion analysis. (A) DNA sequences of the deletion junctions, including 5 and 9 bp microhomologies in shadow, showing the locations of deletion breakpoints in between. (B) The GNAS locus showing the positions of the forward (F1 and F2) and reverse (R1 and R2) primers used for polymerase chain reactions to demonstrate the microdeletions. (C) Gel showing the presence of amplified DNA segments corresponding to the presence of the GNAS deletions present in proband 1 and proband 2; a short extension time (20 seconds) of PCR was used to eliminate amplification of the wild-type alleles.

Similarly, WGS of DNA from proband 2 and his mother with PPHP, followed by bioinformatic analyses and Sanger sequencing, revealed that both patients had a small, heterozygous deletion (1438 bp) that involves partial loss of exon 1 and partial loss of the intronic region between exon A/B and exon 1 (Fig. 1A). His father and unaffected sister had wild-type alleles (Fig. 1B). The 1438 bp deletion was supported by all 5 SV detection programs. The proximal breakpoint of the deletion maps within the (GCC)n repeat that is located between 20(GRCh37):g.57,465,300 and 20(GRCh37):g.57,465,392 and the distal breakpoint maps within another (GCC)n repeat between 20(GRCh37):g.57,466,735 and 20(GRCh37):g.57,466,781, which allowed us to determine this deletion is likely mediated by the simple repeats, nonallelic homologous recombination (NAHR) mechanism (47), with deletion breakpoints located at 20(GRCh37):g.57,465,324-57,465,332 and 20(GRCh37):g.57,466,762-57,466,770. However, we observed a direct 9 bp microhomology (CGGCGGCGG; Fig. 1A) in the breakpoints, therefore FoSTeS or MMBIR represent alternative mechanisms for the deletion formation.

Because the proximal breakpoint of the second deletion is close to the DMR at exon A/B, but does not extend into these CpG sequences, we performed pyrosequencing to investigate the potential effect of either deletion on the imprinting status of the GNAS DMRs. Pyrosequencing analyses showed that control PHP1B patients with STX16 deletions had significantly (P < .01) less methylation at the exon A/B DMR than either normal subjects or patients with PHP1A (Table 1). By contrast, there were no differences between the groups for methylation at the other DMRs. Patient 2 showed a slightly reduced average methylation level (32%) at CpGs within exon A/B of GNAS (Fig. 1A and Table 1) compared with normal subjects and patients with PHP1A, but greater than in PHP1B patients who carry an STX16 deletion (Table 1). By contrast, we observed a normal methylation level (57%) in patient 1 at exon A/B of GNAS (Fig. 1A). For both patients, the level of methylation was similar at each CpG that we assayed (Table 2), either normal (patient 1) or reduced (patient 2). The methylation status of both NESP55- and XLαs-DMRs were normal in both patients (Table 1). In addition, methylation status of the nearby imprinted gene NNAT was also normal in all subjects (data not shown).

Table 1.

Methylation analyses of GNAS DMRs

| Methylation status of DMR, %a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exon A/B (Johns Hopkins)a | Exon A/Bb | XLαs | NESP55 | |

| Patient 1 | 45 | 57 | 38 | 41 |

| Patient 2 | 34 | 32 | 38 | 40 |

| Normal | >43 | |||

| Normal n = 7 | 64 ± 5 | 42 ± 2 | 40 ± 16 | |

| PHP1A, n = 3 | 63 ± 4 | 42 ± 5 | 39 ± 2 | |

| PHP1B (STX16 del) n = 9 | 3 ± 5 | 43 ± 4 | 43 ± 5 | |

aJohns Hopkins assesses cytosine methylation at CpG at chr20:57,464,763-57,464,814 on hg19. See Methods.

bCHOP pyrosequencing assesses cytosine methylation at CpG at chr20:57,464,773-57,464,927 on hg19;

Table 2.

Human GNAS methylation analysis

| ADS464FS1 | ADS464FS2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| From ATG | 49612 | 49619 | 49627 | 49629 | 49634 | 49636 | 49642 | 49650 | 49652 | 49655 | 49662 | 49677 | 49682 | 49687 | 49691 | 49698 | 49707 | 49713 | 49732 | 49741 | 49743 | 49748 | 49757 | 49766 |

| From TSS | 50001 | 50008 | 50016 | 50018 | 50023 | 50025 | 50031 | 50039 | 50041 | 50044 | 50051 | 50066 | 50071 | 50076 | 50080 | 50087 | 50096 | 50102 | 50121 | 50130 | 50132 | 50137 | 50146 | 50155 |

| GRCh38/hg38 Chrom 20 | 58889718 | 58889725 | 58889733 | 58889735 | 58889740 | 58889742 | 58889748 | 58889756 | 58889758 | 58889761 | 58889768 | 58889783 | 58889788 | 58889793 | 58889797 | 58889804 | 58889813 | 58889819 | 58889838 | 58889847 | 58889849 | 58889854 | 58889863 | 58889872 |

| GRCh37/hg19 Chrom 20 | 57464773 | 57464780 | 57464788 | 57464790 | 57464795 | 57464797 | 57464803 | 57464811 | 57464813 | 57464816 | 57464823 | 57464838 | 57464843 | 57464848 | 57464852 | 57464859 | 57464868 | 57464874 | 57464893 | 57464902 | 57464904 | 57464909 | 57464918 | 57464927 |

| Patient 1 | 55.7 | 52.1 | 57.1 | 60.4 | 55.9 | 53.9 | 59.3 | 57.4 | 52.5 | 55.3 | 56.7 | 56.2 | 53.6 | 52.9 | 56.8 | 54.5 | 58.1 | 59.8 | 56.7 | 60.3 | 56.9 | 61.0 | 58.5 | 56.7 |

| Patient 2 | 36.8 | 33.9 | 37.2 | 37.2 | 37.4 | 31.9 | 38.1 | 35.7 | 34.4 | 33.3 | 34.0 | 32.5 | 24.8 | 30.8 | 29.4 | 21.5 | 25.3 | 31.9 | 29.1 | 28.8 | 27.1 | 28.8 | 26.6 | 36.7 |

| Low | 7.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6.7 | 0.0 | 12.4 | 5.3 | 5.6 | 2.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Med | 80.8 | 75.1 | 79.9 | 77.0 | 74.5 | 72.5 | 85.1 | 79.2 | 72.7 | 71.9 | 85.3 | 81.9 | 70.9 | 72.6 | 77.4 | 64.0 | 83.8 | 85.0 | 81.5 | 78.5 | 76.6 | 83.8 | 68.2 | 80.0 |

| High | 90.7 | 86.7 | 99.5 | 93.0 | 90.1 | 93.6 | 98.4 | 93.1 | 89.7 | 87.9 | 99.1 | 100 | 92.7 | 90.7 | 91.3 | 94.3 | 93.3 | 91.0 | 94.9 | 92.5 | 95.6 | 93.0 | 89.9 | 98.4 |

Results in % methylation.

Discussion

We describe here 3 patients with PHP1A/PPHP from 2 families whom we found to carry small heterozygous GNAS intragenic deletions that each affect one exon. Patient 1 carries a 6393 bp deletion that includes all of exon 2 (73 bp), and is predicted to result in a truncated, nonfunctional Gsα protein (p.G49Afs*27) that leads to PHP1A. The second heterozygous deletion, 20(GRCh37):g.57,465,324-57,466,761 (or extends to 20(GRCh37):g.57,465,333-57,466,770 because of repeat sequences on the both ends), removes the sequences in regulatory region of Gsα (including the putative promoter region and 5′ untranslated region) but leaves the reading frame intact without deleting any coding sequences. In general, no transcript is produced if the promoter is missing. We propose that this deletion impairs Gsα expression and results in PHP1A or PPHP.

It has been increasingly acknowledged that 4 major mechanisms (45-49) can account for the formation of structural gene variants, including NAHR, replicative mechanism (eg, FoSTeS and MMBIR), nonhomologous end-joining, and long interspersed nuclear element-mediated retrotransposition or mobile element insertions. It has been appreciated that NAHR often causes recurrent deletion where the deletion is flanked by LCRs or Alu sequences, whereas the replicative mechanism is associated with nonrecurrent deletion (46, 49). For the 6.4 kb deletion, the presence of 5 bp microhomologies at the breakpoint junctions and absence of LCRs and Alu elements highly suggest that a replicative mechanism is responsible for the intragenic deletion. Due to repetitive sequences in the breakpoint junctions of the second deletion (1.4 kb), one may argue it could also be mediated by FoSTeS/MMBIR mechanism, as there are multiple microhomology sequences (eg, CCGCCGCCGCCGC or GCCGCC) in or near the breakpoints. However, considering the replication-based mechanism, break-induced replication and repair would generate more GCC repeats deletion in both ends and that would not match the Sanger sequencing results as shown in Fig. 1A. Thus, we speculate the LCRs flanking the breakpoint junctions are more likely the basis for NAHR-mediated deletion.

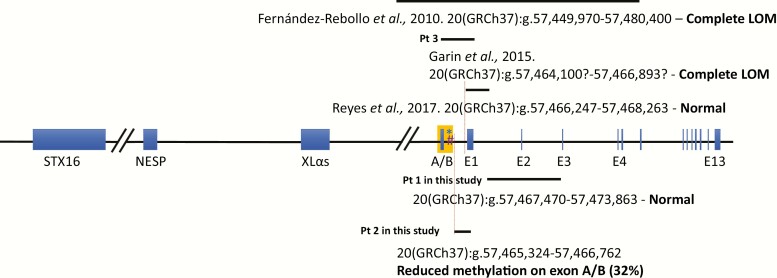

A variety of pathogenic GNAS mutations have been identified in patients with PHP1A/PPHP (34, 50, 51), including point mutations, small coding indels, exon inversion and deletions (52, 53), and a few chromosomal rearrangements (52, 54-56) (ie, big deletions covering the entire GNAS locus). However, so far, only 3 smaller intragenic deletions (eg, bigger than 1 kb but smaller than 50 kb) disrupting the exon A/B or being close to the exon A/B have been identified by CGH array and multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification, to cause PHP1A (Fig. 2) (52, 57, 58). Specifically, a deletion of 30 431 bp starting from the intronic region between exons XL and A/B to intron 5 inherited from maternal allele, which as expected, led to an apparent loss of methylation at exon A/B DMR (57), a second deletion comprising exon A/B to exon 1 resulted in a methylation defect limited to the exon A/B DMR (52), and a third 2015-bp deletion consisting of the entire exon 1 and the flanking intronic regions that caused no abnormal methylation at exon A/B DMR (58). The loss of methylation within the exon A/B DMR in patients carrying the first 2 deletions likely reflects the inclusion of the assayed CpG sequences within the deleted region of genomic DNA. In this situation, only the unmethylated CpGs of the paternal exon A/B DMR are present, which gives an impression of an epigenetic loss of methylation when in fact there is actually a physical loss of methylated DNA. One can implicate a similar but reciprocal mechanism for the gain of methylation at upstream DMRs in some patients with PHP1B who have deletions in the NESP, XLαs, and NESPAS exons of GNAS that include DMRs (28, 31-33). By contrast, the third previously published deletion, which comprises only the E1 exon and the surrounding intronic region, did not lead to a methylation change in the exon A/B DMR (58). Hence, it is remarkable that the deletion that we identified in patient 2, which also does not include exon A/B, does in fact lead to a moderate reduction in methylation of the exon A/B DMR. Although PHP1A is not thought to be an imprinting disorder, deletions inherited on the maternal allele that physically disrupt exon A/B, the corresponding DMR, or, as we demonstrate here, a putative control region, can cause an apparent or real loss of methylation at exon A/B that might potentially lead to a misdiagnosis of PHP1B. Nevertheless, we would note that most so-called PHP1A patients with GNAS imprinting defects show a global imprinting alteration at all DMRs rather than an isolated A/B loss of methylation.

Figure 2.

Breakpoint structures of smaller intragenic deletions disrupting the exon A/B or being close to the exon A/B in PHP1A patients. The 3 reported deletions were shown above the schematic representation of GNAS locus and the 2 deletions at the bottom were identified in this study. Genomics coordinates for each of the alternative first exons of GNAS and DMR regions that were assayed: *Johns Hopkins DMR: 20(GRCh37):g.57,464,763-57,464,814; #CHOP DMR: 20(GRCh37):g.57,464,773-57,464,927; NESP: 20(GRCh37):g.57,414,795-57,415,941; XLαs: 20(GRCh37):g.57,428,036-57,430,388; A/B: 20(GRCh37):g.57,464,180-57,464,408; E1: 20(GRCh37):g.57,466,426-57,466,920.

Exon A/B is located within a CpG island that extends into exon 1 of GNAS. While exon A/B and the flanking intronic sequences constitute a DMR in which the maternal allele is preferentially methylated, the CpG sequences within exon 1 of GNAS do not exhibit a methylation profile that is based on the parent-of-origin of the allele (8, 9, 59). The deletion in patient 2 now identifies sequences 924 bp (or 915 bp) upstream (centromeric) of the deletion described by Reyes et al. (58), (20(GRCh37):g.57,466,248-57,468,262) that may be part of a region that, together with sequences in STX16, appear to be critical for establishing or maintaining parent-specific methylation at GNAS exon A/B. An alternative possibility is that this deletion might exert an indirect effect related to its close physical position to the critical region. Additional studies will be necessary to determine the exact boundaries of this region in GNAS, but the deletion that we have identified certainly establishes its existence.

Our results also demonstrate the usefulness of WGS in the investigation of patients with PHP1A. WGS can detect relatively small deletions with greater sensitivity than conventional CGH or single nucleotide polymorphism microarray, as well as WES, in which copy number variation calling often needs at least three contiguous exons deleted or duplicated (60). Exon 1 of GNAS, as well exon 1 for many other genes (if not all), is more difficult to analyze in WES, multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification, and other PCR-based methods due to a very high GC content. Accordingly, WGS or targeted next generation sequencing of chromosome 20q might be useful as a single test to capture nearly all genetic variations and novel intragenic small deletions in GNAS in patients with PPHP/PHP1A as well as progressive osseous heteroplasia (61, 62). Similarly, WGS (63) or targeted next generation sequencing of the GNAS locus (28) may also be useful in identifying small genetic defects that lead to disturbed imprinting of GNAS in patients with PHP1B.

Our work has several strengths, including the use of pyrosequencing to evaluate methylation of GNAS DMRs in a highly quantitative manner (64) and the application of WGS as an unbiased approach to molecular diagnosis. Our study also has several weaknesses, specifically the inability to ascertain all subjects in both families and the lack of protein samples from affected subjects to confirm the effects of the mutations on synthesis of Gsα,

In summary, we have studied 3 patients in 2 families with PHP1A/PPHP in whom we used WGS to identify novel deletions that were not detected by conventional analyses. In the first case, a deletion in the Gsα promoter leads to PHP1A, presumably by decreasing transcription of Gsα. In the second case, a small deletion (1.4 kb) defines a region that may be critical for normal imprinting of the exon A/B DMR. Our work highlights the complexity of the control mechanism for imprinting of GNAS, and suggests a basis for the reduced methylation of the exon A/B DMR in some patients with PHP1A. Future studies will be necessary to define this control region completely, and to identify the putative proteins that bind to this region.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the families involved in this study for their participation; Fengxiang Wang, James Snyder, and Harsh Kanwar, who helped in the DNA sample extraction and handling; and Tiancheng Wang, who provided technical assistance.

Financial Support: R01DK112955 (MAL), and the CHOP Research Institute.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AHO

Albright hereditary osteodystrophy

- AS

antisense transcript

- CGH

comparative genome hybridization

- CGH

comparative genome hybridization

- DMR

differentially methylated regions

- DNA

deoxyribonucleic acid

- indel

insertion/deletion

- LCR

low copy repeat

- NAHR

nonallelic homologous recombination

- NESP55

neuroendocrine secretory protein 55

- PHP1A

pseudohypoparathyroidism type 1A

- PPHP

pseudopseudohypoparathyroidism

- PTH

parathyroid hormone

- SV

structural variation

- TSH

thyrotropin

- WES

whole exome sequence

- WGS

whole genome sequencing

Additional Information

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Data Availability: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article or in the data repositories listed in References.

References

- 1. Levine MA. An update on the clinical and molecular characteristics of pseudohypoparathyroidism. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2012;19(6):443-451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mantovani G, Bastepe M, Monk D, et al. Diagnosis and management of pseudohypoparathyroidism and related disorders: first international consensus statement. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2018;14(8):476-500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Albright F, Forbes AP, Henneman PH. Pseudo-pseudohypoparathyroidism. Trans Assoc Am Physicians. 1952;65: 337-350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Eyre WG, Reed WB. Albright’s hereditary osteodystrophy with cutaneous bone formation. Arch Dermatol. 1971;104(6):634-642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Patten JL, Johns DR, Valle D, et al. Mutation in the gene encoding the stimulatory G protein of adenylate cyclase in Albright’s hereditary osteodystrophy. N Engl J Med. 1990;322(20):1412-1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Weinstein LS, Gejman PV, Friedman E, et al. Mutations of the Gs alpha-subunit gene in Albright hereditary osteodystrophy detected by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87(21):8287-8290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Levine MA, Modi WS, O’Brien SJ. Mapping of the gene encoding the alpha subunit of the stimulatory G protein of adenylyl cyclase (GNAS1) to 20q13.2––q13.3 in human by in situ hybridization. Genomics. 1991;11(2):478-479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hayward BE, Kamiya M, Strain L, et al. The human GNAS1 gene is imprinted and encodes distinct paternally and biallelically expressed G proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(17):10038-10043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hayward BE, Moran V, Strain L, Bonthron DT. Bidirectional imprinting of a single gene: GNAS1 encodes maternally, paternally, and biallelically derived proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(26):15475-15480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bastepe M. The GNAS locus and pseudohypoparathyroidism. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;626:27-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bastepe M. Genetics and epigenetics of parathyroid hormone resistance. Endocr Dev. 2013;24:11-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mantovani G, Spada A, Elli FM. Pseudohypoparathyroidism and Gsα-cAMP-linked disorders: current view and open issues. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2016;12(6):347-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chen M, Wang J, Dickerson KE, et al. Central nervous system imprinting of the G protein G(s)alpha and its role in metabolic regulation. Cell Metab. 2009;9(6):548-555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Klenke S, Siffert W, Frey UH. A novel aspect of GNAS imprinting: higher maternal expression of Gαs in human lymphoblasts, peripheral blood mononuclear cells, mammary adipose tissue, and heart. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2011;341(1-2):63-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Liu J, Erlichman B, Weinstein LS. The stimulatory G protein alpha-subunit Gs alpha is imprinted in human thyroid glands: implications for thyroid function in pseudohypoparathyroidism types 1A and 1B. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(9):4336-4341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mantovani G, Ballare E, Giammona E, Beck-Peccoz P, Spada A. The gsalpha gene: predominant maternal origin of transcription in human thyroid gland and gonads. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87(10):4736-4740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mantovani G, Bondioni S, Locatelli M, et al. Biallelic expression of the Gsalpha gene in human bone and adipose tissue. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(12):6316-6319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zheng H, Radeva G, McCann JA, Hendy GN, Goodyer CG. Galphas transcripts are biallelically expressed in the human kidney cortex: implications for pseudohypoparathyroidism type 1b. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86(10):4627-4629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Weinstein LS, Yu S, Ecelbarger CA. Variable imprinting of the heterotrimeric G protein G(s) alpha-subunit within different segments of the nephron. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2000;278(4):F507-F514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Davies SJ, Hughes HE. Imprinting in Albright’s hereditary osteodystrophy. J Med Genet. 1993;30(2):101-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nakamoto JM, Sandstrom AT, Brickman AS, Christenson RA, Van Dop C. Pseudohypoparathyroidism type Ia from maternal but not paternal transmission of a Gsalpha gene mutation. Am J Med Genet. 1998;77(4):261-267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liu J, Litman D, Rosenberg MJ, Yu S, Biesecker LG, Weinstein LS. A GNAS1 imprinting defect in pseudohypoparathyroidism type IB. J Clin Invest. 2000;106(9):1167-1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. de Nanclares GP, Fernández-Rebollo E, Santin I, et al. Epigenetic defects of GNAS in patients with pseudohypoparathyroidism and mild features of Albright’s hereditary osteodystrophy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(6):2370-2373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mariot V, Maupetit-Méhouas S, Sinding C, Kottler ML, Linglart A. A maternal epimutation of GNAS leads to Albright osteodystrophy and parathyroid hormone resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(3):661-665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Unluturk U, Harmanci A, Babaoglu M, et al. Molecular diagnosis and clinical characterization of pseudohypoparathyroidism type-Ib in a patient with mild Albright’s hereditary osteodystrophy-like features, epileptic seizures, and defective renal handling of uric acid. Am J Med Sci. 2008;336(1):84-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mantovani G, de Sanctis L, Barbieri AM, et al. Pseudohypoparathyroidism and GNAS epigenetic defects: clinical evaluation of Albright hereditary osteodystrophy and molecular analysis in 40 patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(2):651-658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Molinaro A, Tiosano D, Takatani R, et al. TSH elevations as the first laboratory evidence for pseudohypoparathyroidism type Ib (PHP-Ib). J Bone Miner Res. 2015;30(5):906-912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rezwan FI, Poole RL, Prescott T, Walker JM, Karen Temple I, Mackay DJ. Very small deletions within the NESP55 gene in pseudohypoparathyroidism type 1b. Eur J Hum Genet. 2015;23(4):494-499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bastepe M, Lane AH, Jüppner H. Paternal uniparental isodisomy of chromosome 20q–and the resulting changes in GNAS1 methylation–as a plausible cause of pseudohypoparathyroidism. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68(5):1283-1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bastepe M, Fröhlich LF, Hendy GN, et al. Autosomal dominant pseudohypoparathyroidism type Ib is associated with a heterozygous microdeletion that likely disrupts a putative imprinting control element of GNAS. J Clin Invest. 2003;112(8):1255-1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bastepe M, Fröhlich LF, Linglart A, et al. Deletion of the NESP55 differentially methylated region causes loss of maternal GNAS imprints and pseudohypoparathyroidism type Ib. Nat Genet. 2005;37(1):25-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chillambhi S, Turan S, Hwang DY, Chen HC, Jüppner H, Bastepe M. Deletion of the noncoding GNAS antisense transcript causes pseudohypoparathyroidism type Ib and biparental defects of GNAS methylation in cis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(8):3993-4002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Richard N, Abeguilé G, Coudray N, et al. A new deletion ablating NESP55 causes loss of maternal imprint of A/B GNAS and autosomal dominant pseudohypoparathyroidism type Ib. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(5):E863-E867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lemos MC, Thakker RV. GNAS mutations in Pseudohypoparathyroidism type 1a and related disorders. Hum Mutat. 2015;36(1):11-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(14):1754-1760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. DePristo MA, Banks E, Poplin R, et al. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat Genet. 2011;43(5):491-498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(16):e164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cingolani P, Platts A, Wang le L, et al. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly (Austin). 2012;6(2):80-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chen K, Wallis JW, McLellan MD, et al. BreakDancer: an algorithm for high-resolution mapping of genomic structural variation. Nat Methods. 2009;6(9):677-681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chen X, Schulz-Trieglaff O, Shaw R, et al. Manta: rapid detection of structural variants and indels for germline and cancer sequencing applications. Bioinformatics. 2016;32(8):1220-1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kronenberg ZN, Osborne EJ, Cone KR, et al. Wham: identifying structural variants of biological consequence. PLoS Comput Biol. 2015;11(12):e1004572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Abyzov A, Urban AE, Snyder M, Gerstein M. CNVnator: an approach to discover, genotype, and characterize typical and atypical CNVs from family and population genome sequencing. Genome Res. 2011;21(6):974-984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chiang C, Layer RM, Faust GG, et al. SpeedSeq: ultra-fast personal genome analysis and interpretation. Nat Methods. 2015;12(10):966-968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Layer RM, Chiang C, Quinlan AR, Hall IM. LUMPY: a probabilistic framework for structural variant discovery. Genome Biol. 2014;15(6):R84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lee JA, Carvalho CM, Lupski JR. A DNA replication mechanism for generating nonrecurrent rearrangements associated with genomic disorders. Cell. 2007;131(7):1235-1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hastings PJ, Lupski JR, Rosenberg SM, Ira G. Mechanisms of change in gene copy number. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10(8):551-564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lupski JR. Genomic disorders: structural features of the genome can lead to DNA rearrangements and human disease traits. Trends Genet. 1998;14(10):417-422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Stankiewicz P, Lupski JR. Genome architecture, rearrangements and genomic disorders. Trends Genet. 2002;18(2):74-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Carvalho CM, Lupski JR. Mechanisms underlying structural variant formation in genomic disorders. Nat Rev Genet. 2016;17(4):224-238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Fischer JA, Egert F, Werder E, Born W. An inherited mutation associated with functional deficiency of the alpha-subunit of the guanine nucleotide-binding protein Gs in pseudo- and pseudopseudohypoparathyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83(3):935-938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Thiele S, Werner R, Grötzinger J, et al. A positive genotype-phenotype correlation in a large cohort of patients with Pseudohypoparathyroidism Type Ia and Pseudo-pseudohypoparathyroidism and 33 newly identified mutations in the GNAS gene. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2015;3(2):111-120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Garin I, Elli FM, Linglart A, et al. Novel microdeletions affecting the GNAS locus in pseudohypoparathyroidism: characterization of the underlying mechanisms. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(4):E681-E687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Fernandez-Rebollo E, Barrio R, Pérez-Nanclares G, et al. New mutation type in pseudohypoparathyroidism type Ia. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2008;69(5):705-712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Geneviève D, Sanlaville D, Faivre L, et al. Paternal deletion of the GNAS imprinted locus (including Gnasxl) in two girls presenting with severe pre- and post-natal growth retardation and intractable feeding difficulties. Eur J Hum Genet. 2005;13(9):1033-1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Mitsui T, Nagasaki K, Takagi M, Narumi S, Ishii T, Hasegawa T. A family of pseudohypoparathyroidism type Ia with an 850-kb submicroscopic deletion encompassing the whole GNAS locus. Am J Med Genet A. 2012;158A(1):261-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Aldred MA, Aftimos S, Hall C, et al. Constitutional deletion of chromosome 20q in two patients affected with Albright hereditary osteodystrophy. Am J Med Genet. 2002;113(2):167-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Fernandez-Rebollo E, García-Cuartero B, Garin I, et al. Intragenic GNAS deletion involving exon A/B in pseudohypoparathyroidism type 1A resulting in an apparent loss of exon A/B methylation: potential for misdiagnosis of pseudohypoparathyroidism type 1B. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(2):765-771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Reyes M, Karaca A, Bastepe M, Gulcelik NE, Jüppner H. A novel deletion involving GNAS exon 1 causes PHP1A and further refines the region required for normal methylation at exon A/B. Bone. 2017;103:281-286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Hayward BE, Bonthron DT. An imprinted antisense transcript at the human GNAS1 locus. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9(5):835-841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. de Ligt J, Boone PM, Pfundt R, et al. Detection of clinically relevant copy number variants with whole-exome sequencing. Hum Mutat. 2013;34(10):1439-1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Eddy MC, Jan De Beur SM, Yandow SM, et al. Deficiency of the alpha-subunit of the stimulatory G protein and severe extraskeletal ossification. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15(11):2074-2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Shore EM, Ahn J, Jan de Beur S, et al. Paternally inherited inactivating mutations of the GNAS1 gene in progressive osseous heteroplasia. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(2):99-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Li D, Hakonarson H, Levine MA. A Recurrent 6-bp Intronic Deletion in NESP55 with Reduced Penetrance in Pseudohypoparathyroidism Type 1b. In 57th Annual ESPE. European Society for Paediatric Endocrinology; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Elli FM, de Sanctis L, Bollati V, et al. Quantitative analysis of methylation defects and correlation with clinical characteristics in patients with pseudohypoparathyroidism type I and GNAS epigenetic alterations. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(3):E508-E517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]