Abstract

Background

Acute myocardial infarction in pregnancy is occasionally due to spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD). Although uncommon, the majority of cases of pregnancy-associated SCAD (pSCAD) has critical presentations with more profound defects that portend high maternal and foetal mortality, and frequently necessitate preterm delivery. This is a case of pSCAD with ongoing ischaemia that required temporary mechanical circulatory support (MCS) and emergent revascularization, while the pregnancy was successfully continued to early-term.

Case summary

A 30-year-old woman G2P1 at Week 32 of gestation with no medical history, presented to the emergency department with severe chest pain. An electrocardiogram showed ST-segment elevation in the anterolateral leads. An emergent cardiac catheterization revealed dissection of the proximal left anterior descending (LAD) artery with TIMI (thrombolysis in myocardial infarction) 3 flow. Although initially stable, she later experienced recurrent chest pain and developed cardiogenic shock, necessitating MCS, and emergent revascularization. She was stabilized and remained closely monitored in the hospital prior to vaginal delivery at early-term.

Discussion

This case of pSCAD at Week 32 of gestation complicated by refractory ischaemia illustrates the complexity of management, which requires a multi-disciplinary team to reduce both maternal and foetal mortality. Conservative management of SCAD, while preferred, is not always possible in the setting of ongoing ischaemia, particularly if complicated by cardiogenic shock. A thorough weighing of risks vs. benefits and ongoing discussions among multiple subspecialists in this case allowed for the stabilization of the patient and subsequent successful early-term delivery.

Keywords: SCAD, Shock, Cardio-obstetrics, ACS, Revascularization, Case report

Learning points

Maintain a high index of suspicion for spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) in younger, especially pregnant women presenting with acute coronary syndrome (ACS).

A multidisciplinary approach is required for the management of SCAD during pregnancy with ongoing ischaemia.

There is a paucity of information regarding the use of mechanical circulatory support during pregnancy and consideration of use necessitates extensive discussion of risks vs. benefits.

Introduction

Spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) is an uncommon cause of acute coronary syndrome (ACS), most often occurring in young females without traditional cardiovascular disease risk factors. Risk factors include hormonal fluctuations, systemic inflammatory states, arteriopathies, and connective tissue disorders. Pregnancy-associated spontaneous coronary artery dissection (pSCAD) is associated with dissection of more prominent epicardial vessels, often resulting in extensive myocardial injury. Patients typically present with ACS complicated by acute heart failure or cardiogenic shock.1

Timeline

| Day 0 | Initial presentation and evaluation |

|

| Day 1 | Transfer to tertiary centre for maternal foetal medicine service and presentation to tertiary care centre |

|

| Day 1 | Intervention |

|

| Day 2–40 | Post-operative course: initial admission to cardiovascular intensive care unit (CVICU) and transferred to high-risk perinatal unit once stable |

|

| Day 41–43 | Post-operative course: delivery |

|

| Day 44–365 | Post-discharge follow-up |

|

Case presentation

A 30-year-old Caucasian female G2P1 at Week 32 of gestation presented to an outside hospital with complaints of severe (10/10), substernal chest pain which began 2 h prior to presentation. The pain was non-radiating and associated with dyspnoea; it was not alleviated by nitroglycerine. She had no prior medical or surgical history other than a prior uncomplicated vaginal delivery. She had a 12 pack-year history of smoking; and the only medication she was taking prior to admission was pre-natal vitamins.

The patient was afebrile, normotensive, tachycardic, and saturating well on room air. She was in mild distress with slightly laboured breathing, diaphoresis, and an elevated jugular venous pressure. She exhibited 2+ oedema of bilateral lower extremities.

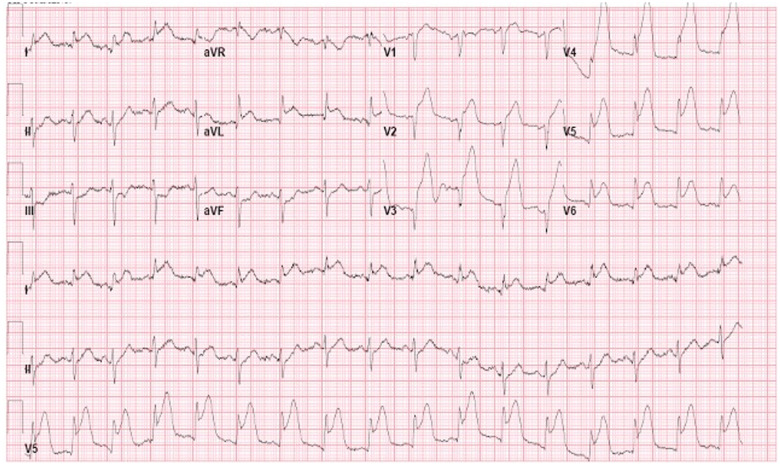

An EKG revealed ST-elevation in the anterolateral leads (Figure 1). Initial troponin was mildly elevated. Differential diagnoses considered at the time included: coronary artery dissection, acute plaque rupture, myocarditis, and stress-induced cardiomyopathy. Given the age of the patient and current pregnancy, coronary artery dissection was suspected. In the setting of ST-elevation ACS, she underwent emergent cardiac catheterization, which revealed a dissection of the proximal left anterior descending artery (LAD) and an intramural haematoma involving a large diagonal with preserved distal flow (Figure 2). Elevated left ventricular end-diastolic pressure of 35 mmHg was noted.

Figure 1.

Electrocardiogram revealing acute anterolateral infarct.

Figure 2.

Coronary angiogram with left anterior descending artery dissection and intramural haematoma.

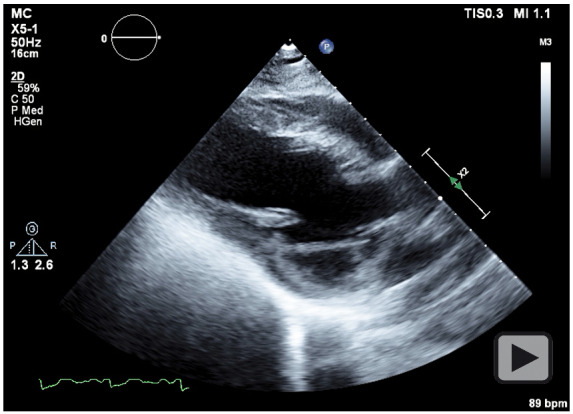

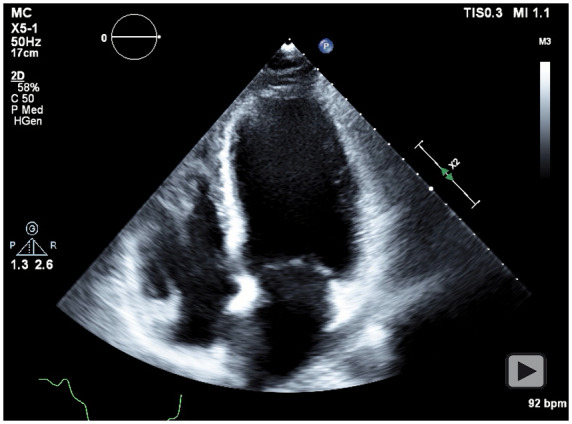

Considering the risk of exacerbating the dissection, PCI was avoided in favour of conservative management. Maternal foetal medicine (MFM) subspecialists were not available at the facility therefore the patient was transferred to a tertiary centre. During transfer, the severe chest pain recurred; and she became hypotensive. Upon arrival, an EKG showed persistent ST elevation. Transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) revealed a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of <20% with anterior and apical akinesis; chest X-ray showed bilateral pulmonary oedema (Figures 3 and 4). A multidisciplinary discussion ensued amongst; MFM, cardiothoracic surgeon, interventional cardiologist, and cardiac anaesthesiologist. The patient developed cardiogenic shock necessitating emergent intervention, and a percutaneous left ventricular assist device (Impella®) was placed. Subsequently, an emergent coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) was performed with two-vessel bypass of the left internal mammary artery (LIMA) to LAD and a saphenous vein graft (SVG) to diagonal.

Figure 3.

Transthoracic echocardiogram, parasternal long-axis view showing reduced left ventricular systolic function.

Figure 4.

Transthoracic echocardiogram, apical four-chamber view showing reduced left ventricular systolic function.

Continuous foetal monitoring was conducted while Impella® support was weaned. Aspirin and metoprolol were initiated. Furosemide was given intravenously (IV) as needed. Additional guideline directed medical therapy was held due to contraindication in pregnancy. Daily multidisciplinary rounds were conducted to discuss optimal timing for delivery which was planned for weeks 37–39 of gestation. The patient stabilized and was transferred to the high-risk peripartum unit awaiting delivery. At Week 38 of gestation, labour was induced with close haemodynamic monitoring in the cardiovascular intensive care unit (CVICU) resulting in the uncomplicated birth of a viable male via forceps-assisted passive second stage vaginal delivery. An additional dose of furosemide was administered upon clamping of the umbilical cord to mitigate major volume shifts. The patient was discharged on postpartum Day 2.

The patient followed up with cardiology 3 weeks after discharge. She was taking aspirin 81 mg daily and metoprolol succinate 12.5 mg daily. Low blood pressure precluded additional agents at the time; lisinopril 2.5 mg daily and spironolactone 12.5 mg daily were later added. Three months following discharge, repeat TTE showed an LVEF of 30–35%. One year after discharge, a dual-chamber implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) was placed. Additional imaging assessed for extracoronary vascular abnormalities, and no other vascular pathology was identified. She maintains regular follow-up with cardiology and the child has had normal development.

Discussion

Spontaneous coronary artery dissection is defined by the formation of a false lumen within the intima, without underlying plaque or iatrogenic provocation, likely from haemorrhage of vasa vasorum into the vessel wall. This may lead to compression of the true lumen and subsequent compromise of blood flow.3 In young women, SCAD is the aetiology behind ∼20% of ACS cases.3 Women with SCAD are often free of traditional cardiovascular risk factors. Fibromuscular dysplasia, systemic inflammatory syndromes, connective tissue diseases, and pregnancy have been identified as risk factors, with acute physical and emotional stressors as possible exacerbating triggers. pSCAD is the most common cause of ACS in pregnant or postpartum women, typically occurring in the third trimester or early postpartum period. Initial management should be conservative, due to the potential for iatrogenic exacerbation. PCI has been associated with expansion of dissections and worsening of cardiac haemodynamics.2 In the case of ongoing ischaemia or haemodynamic instability, early revascularization is warranted; if left main or proximal dissections are present or there are complications with PCI, CABG can be performed. 7

Pregnancy-associated SCAD is associated with more extensive myocardial insults, thus cardiogenic shock and life-threatening arrhythmias are not uncommon developments. Mechanical circulatory support (MCS) may be considered, often in conjunction with revascularization or rarely with cardiac transplantation.4 Extra-corporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP), and left ventricular assist device (LVAD) have been used, but their role during pregnancy is not well established.5 Few case reports describe use of ECMO for SCAD during the post-partum period; however, it is rarely used during pregnancy.6 The anticoagulation requirement introduces a substantial bleeding risk during caesarean section, thus MCS is more commonly initiated after delivery.1 Intra-aortic balloon pump has been used to support patients through surgical delivery of the foetus as a bridge to revascularization. Left ventricular assist devices can augment forward flow and are most commonly used after revascularization.5 The effects of MCS on foetal placental haemodynamics and ideal foetal monitoring strategy remain unclear.

Maternal mortality rates associated with cardiovascular surgery during pregnancy have improved, with rates similar to those in non-pregnant women. Foetal mortality rate is as high as 33%, dependent upon multiple factors: placental and foetal response to bypass, urgency of operation, and gestational age.7 Most women with cardiovascular disease are not precluded from vaginal deliveries; however, they may require an assisted passive second stage of delivery to mitigate cardiac strain. Routine blood loss during a caesarean section may also increase cardiac demand. A multidisciplinary team versed in the haemodynamics of pregnancy and delivery is paramount for improved outcomes; delivery commonly occurs in the CVICU for close monitoring. During the first 24–48 h postpartum, auto-transfusion of blood and volume from uterine involution and third-spaced fluid is expected. This volume is not insignificant in patients with cardiomyopathy, who may benefit from a period of observation to assess for volume overload and respiratory distress.8

In this case, the patient was involved in early open discussions with the multidisciplinary team. Maternal and foetal risks were discussed extensively, and the patient desired to continue the pregnancy despite the risk. Percutaneous left ventricular assist device (Impella®) was chosen to offload her left ventricle, further augment forward flow, and maximize haemodynamic stability to reduce maternal and foetal risk during CABG. Ongoing team discussions allowed for effective communication and dynamic planning. Fortunately, despite limited evidence to guide management, there was a successful outcome for both the patient and child.

Lead author biography

Dr Kelly Wingerter is a cardiologist at UMMC specializing in Women’s Cardiovascular Disease. Dr Wingerter has been practicing in Mississippi since 2019 after completing her Cardiovascular Disease fellowship at the University of Tennessee in Chattanooga.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Heart Journal - Case Reports online.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This paper was a pleasure to develop thanks to the contributions of the authors and the help from Dr Yuri Boyechko, Dr Michael Mikolaj, and Dr Matthew Wiisanen. The input and revisions from so many special minds made for a polished and insightful final product. A special thanks to Dr Alison Bailey for coordinating resources across many disciplines and encouraging younger physicians to get involved with research.

Slide sets: A fully edited slide set detailing this case and suitable for local presentation is available online as Supplementary data.

Consent: The authors confirm that written consent for submission and publication of this case report including images and associated text has been obtained from the patient in line with COPE guidance.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Funding: None declared.

References

- 1. Tweet MS, Hayes SN, Codsi E, Gulati R, Rose CH, Best PJ.. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection associated with pregnancy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;70:426–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gilhofer TS, Saw J.. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: a review of complications and management strategies. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther 2019;17:275–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Franke KB, Wong DTL, Baumann A, Nicholls SJ, Gulati R, Psaltis PJ.. Current state-of-play in spontaneous coronary artery dissection. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther 2019;9:281–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Patel A, Asopa S, Tang AT, Ohri SK.. Cardiac surgery during pregnancy. Tex Heart Inst J 2008;35:307–312. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Scott NS. Management of cardiovascular disease during pregnancy. US Cardiol Rev 2018;12:119–123. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Havakuk O, Goland S, Mehra A, Elkayam U.. Pregnancy and the risk of spontaneous coronary artery dissection: an analysis of 120 contemporary cases. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2017;10:e004941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hayes SN, Kim ESH, Saw J, Adlam D, Arslanian-Engoren C, Economy KE. et al. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: current state of the science. a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2018;137:e523–e557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bui P, Mascaro PG, Henao-Mejia J, Patel S.. Preemptive ECMO cannulation in a patient with severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction undergoing cesarean delivery. Case Rep Anesthesiol 2019;2019:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.