Abstract

Background

Paediatric emergency departments have seen reduced attendance during the COVID-19 pandemic. Late paediatric presentations may lead to severe illness and even death. Maintaining provision of healthcare through a pandemic is essential. This qualitative study aims to identify changing care-seeking behaviours in child health during the pandemic and ascertain parental views around barriers to care.

Methods

Semistructured interviews were conducted with caregivers of children accessing acute paediatric services in a hospital in North-West London. Thematic content analysis was used to derive themes from the data, using a deductive approach.

Results

From interviews with 15 caregivers an understanding was gained of care-seeking behaviours during the pandemic. Themes identified were; influencers of decision to seek care, experience of primary care, other perceived barriers, experiences of secondary care, advice to others following lived experience. Where delays in decision to seek care occurred this was influenced predominantly by fear, driven by community perception and experience and media portrayal. Delays in reaching care were focused on access to primary care and availability of services. Caregivers were happy with the quality of care received in secondary care and would advise friends to seek care without hesitation, not to allow fear to delay them.

Conclusion

A pandemic involving a novel virus is always a challenging prospect in terms of organisation of healthcare provision. This study has highlighted parental perspectives around access to care and care-seeking behaviours which can inform us how to better improve service functioning during such a pandemic and beyond into the recovery period.

Keywords: Covid-19, qualitative research, health services research

A qualitative study of parents accessing acute paediatric services. Delays in seeking help were primarily driven by fear of infection. Parents had experienced delays in accessing primary care, but once at secondary care were satisfied with care received.

What is already known on this topic?

Recent epidemics such as Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) and Ebola have had profound effects on non-epidemic-related healthcare utilisation.

Paediatric emergency department attendances reduced during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Late presentation during the pandemic have led to reports of severe illness and death; however, it is unclear if reduced attendances reflect delays in presentation of severe illness.

What this study adds?

The delay in decision to seek care was influenced predominantly by fear, driven by community perception and experience and media portrayal.

Delays in reaching care were focused on access to primary care, accessibility and availability of services.

Caregivers were happy with the quality of care received at secondary care and would advise friends to seek care without hesitation, and not to allow fear to delay them.

Introduction

COVID-19 was declared a public health emergency of international concern on 30 January 2020. Outbreak response, preparedness and redistribution of services was and continues to be the challenge faced by healthcare systems across the globe.

A vast burden of disease is seen in adults, although children of all ages are susceptible.1 Despite COVID-19 having a less severe direct impact on children’s health, the indirect effect of changes in healthcare delivery and perceived access to healthcare have been significant. Recent epidemics such as SARS, MERS and Ebola have had profound effects on non-epidemic-related healthcare utilisation, with reported reductions of 18%–33%.2–5 During the SARS outbreak in Canada 2003, reduced volumes of low acuity patients in the paediatric emergency department (ED) were observed at a time of increased perceived risk and public health advice to stay at home.2

During the current pandemic, late paediatric presentation in the UK and Italy have led to reports of severe illness and death.6–9 Initial indications suggest paediatric ED attendances reduced dramatically during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, with reductions of 73%–88% in Italy and 34% in the UK.8 10 11 In the USA, the Centres for Disease Prevention and Control reported a 42% reduction in ED attendance during the early pandemic, with the largest declines in those under 14 years.12 A small study from Italy reported fear of infection contributing to delayed access to care for severely unwell children.8 However, the evidence is mixed about the extent to which reduced activity reflects delays in presentation of severe illness. A multicentre surveillance study from the UK showed that 93% of ED attendances were not considered by clinicians to be delayed. In the delayed minority, only 12% required admission.13

Maintaining provision of healthcare through a pandemic is essential, in particular for vulnerable patient groups. The pressures posed by the current COVID-19 pandemic may increase the risk of poor mental health and child abuse; simultaneous school closures could result in reduced identification and support for such children.

There is an urgent need to evaluate healthcare beliefs, advice received and utilisation behaviours that might lead to delayed presentation, particularly in view of subsequent surges.

This qualitative study aims to identity changing care-seeking behaviours in child health during the pandemic and ascertain parental views around barriers to care. The results will inform innovations and adaptations in paediatric care during the pandemic or future periods of increased pressure on the healthcare system to improve access and quality of care.

Methods

Study setting and population

The study was conducted during May and June 2020 in the paediatric inpatient department of a busy District General Hospital in North-West London, during the COVID-19 pandemic. The hospital saw a high burden of disease in the early phase of the pandemic, 981 adults hospitalised between 12 March and 15 April 2020 and testing positive for SARS-CoV-2, 345 of whom died (36%).14 Between 23 March and 23 April 2020, 10 children testing positive for SARS-CoV-2 were hospitalised, with no deaths and no transfers to intensive care. A critical incident was declared due to reaching capacity for adult intensive care unit beds on 19 March 2020, which was well publicised in local and national media.

The Trust consists of three hospital sites in three boroughs and serves a population of over 160 000 children and young people.15 Northwick Park Hospital, the study site, is the main hospital inpatient unit and has 26 paediatric beds with an annual paediatric ED attendance of approximately 21 000.

Caregivers, with parental responsibility, of children under 16 years, accessing paediatric acute services via ED, were approached by clinicians following admission to the paediatric ward, informed of the study and asked to contact the research team if interested in participating. Following consent, caregivers were recruited for the study. Interviews took place while the child was an inpatient, in the patient’s room (in keeping with infection control policies at the time). To ensure equity, all reasonable efforts were made to include those with limited English.

Study design and data collection

Semistructured interviews were conducted using iterative interview guides, designed by the research team, to capture emerging themes. Interviews were held by researchers experienced with qualitative research, paediatricians, but not actively involved in the patients care. Interviews were audio recorded and then transcribed.

It was anticipated that 15–20 participants would be required for saturation to be reached. Saturation was reached between 10–15 interviews during the study, and 15 interviews were carried out in total.

Primary objective

To establish care-seeking behaviours for children during the pandemic and any perceived or felt barriers to care for children.

Secondary objective

To identify common themes for perceived or felt barriers to care for children to better inform mitigation in future.

Analysis

All researchers met to discuss the transcripts to capture emerging themes. Transcriptions of audio recordings were exported to ATLAS.ti (Qualitative Data Analysis and Research software). Thematic content analysis was used to derive themes from the data, using a deductive approach. Three authors (GW, LP and BW) compared themes and codes generated for consistency and agreed with the key findings. Illustrating quotations were selected as per Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative reserach (COREQ) guidelines.16

Ethics

The study was carried out in accordance with the principals of Good Clinical Practice.

All participants were over the age of 18 years and written consent was taken prior to enrolment.

Results

A total of 15 interviews were conducted with caregivers; 14 were the mothers and 1 was the father. The median caregiver age was 33 years (range 25–60 years) and participants were from diverse ethnic groups. Children were admitted for a range of common paediatric conditions. For full demographics, see online supplemental table 1 appendix.

archdischild-2020-321260supp001.pdf (36.4KB, pdf)

The following themes were extracted from interviews;

Influencers of decision to seek care

Experience of primary care

Other perceived barriers

Experiences of secondary care

Advice to others following lived experience

Influencers of decision to seek care: (quotes in table 1)

Table 1.

Quotes for influencers of decision to seek care

| 1.1 Lack of signposting | “That was another thing I had to kind of hunt online and didn't know what information was accurate or not, so that was another kind of upsetting situation on top of everything.” |

| 1.2.1 Fear of exposure |

“I was actually quite adamant that I don’t want to come into A&E…And what was your reason you didn’t want to go to A&E? I just felt like he might be exposed to too much there”

“I was worried regarding this virus as well, if I go hospital, I might catch it from there” “Am I exposing myself and my child to COVID-19, are we going to be at a higher risk because were going in… but maybe in retrospect, had COVID-19 not been a thing, maybe when he had his first episode a week and a half ago, maybe I would have brought him in then.” “So, my husband didn’t want to bring him given everything that’s going on, you know worrying that he might catch something more serious. And I was scared too, to bring him in because obviously there are other people and there might be a few people who are infected with COVID-19.” |

| 1.2.2 Fear driven by community |

“He (father) literally said to me people are going in there and not coming out and it was really hard because he’s lost a lot of friends…he said he’d rather die at home than going to hospital and dying alone.”

“I have a friend here, she told me not to come, she was like don’t do it, don’t do it you know, there’s COVID-19, don’t do it and also do you really want to go to A&E, it’s going to be horrible. Yeah, so told me not to come.” |

| 1.2.3. Fear driven by media |

“especially on the news yesterday at some point, so I asked them (paramedics) where are we going, and he said Northwick Park and I said I thought Northwick Park was at full capacity”

“I think there’s just too much crap in the media, I think it’s doing people’s heads in, I think people are confused, worried” “Well normally in the media, even if you dial the number like the GP number or hospital number the first thing is about corona, if its corona don’t come or you know stay home. So it gives you the impression that the corona is coming from the hospital, so I feel like the media are pushing the people not to make the right decisions by coming when they need to come and to stay home if they needed the treatment.” “You do hear a lot of things about this particular hospital, the mortality rate and it’s been in the media a couple of times surrounding COVID-19” |

| 1.3 Knowledge and signposting |

“Because when I went to my antenatal classes and they suggested I download the ‘mum and baby app’ and read everything there, which I did. There’s lots of information which was quite good because then I knew I had to come so, I read it on the NHS website… And they have different articles and they say if it’s (temperature) over 38°C just come in”

“My midwife came on the fifth day to do the checks and blood spots and notice that he was still jaundice and to keep observing and said if there was any change in behaviour, if I notice he was lethargic or not feeding properly then to go to A&E” “When the midwife discharged us from the hospital when I delivered him, she said if the baby gets fever just to come to A&E, so I done that” |

| 1.4 Support and advice from others |

“It was nice hearing a friend as well, because she’s a mother of two, so obviously she has a bit more experience than I do” “My brother said that I had no choice but to come” |

| 1.5 Significant parental concern about child’s health |

“I didn’t think twice about it, I thought my child’s unwell. I didn’t even think about coronavirus when I was coming in.”

“I knew that numbers were going down. Even if they weren't going down, his health is more important, so I would have come to the hospital anyway. I can't risk it, because I'm not a doctor, so I can't. I can only give him Calpol and that’s about it, but I didn't want to risk any complications.” “Even without the pandemic I would have done the same thing, his health is more important” “It wasn't, ‘I would avoid coming in just cause of the pandemic’, for me it was so important, it was worth taking the risk.” “It was clear. I’m a mother, my son was in pain I had to make a decision.” |

| 1.6 Positive experience from NHS 111 directing care |

“To be fair, 111 I think they give good advice in the way they triage is amazing because they kind of go through their tick boxes and put people whether it’s Urgent Care or whether it’s an ambulance.”

“I said to myself, to be honest I need to make a move, I need to call 111 which you know they assist me, they advised me. They were really good on the phone.” “It was actually quite quick. I phoned and they picked up straight away and they told me the doctor will call me in 10–15 min. They called me in 3 min actually, they just call me right back because he is 2 months old. It’s because of an emergency so.” |

A&E, accident and emergency; GP, general practitioner; NHS, National Health Service.

decision-making was influenced by many different factors, themes in common barriers to care-seeking emerged as;

1.1 Lack of signposting

-

1.2 Fear

of direct exposure to SARS-CoV-2

driven by media

driven by community, family and personal experience

Some respondents didn’t know where to find healthcare advice during the pandemic and which channels to follow. Fear was discussed by every respondent and appeared to be driven by numerous factors. Some discussed the perceived risk of direct SARS-CoV-2 transmission when attending ED or following admission to the hospital, either from other patients, staff or hospital appliances. Fear was reported to be driven by the media and by community, family and personal experiences.

However, themes covering facilitation of care-seeking emerged;

1. 3 Knowledge and appropriate signposting

1.4 Advice from others and family support to attend

1. 5 Significant parental concern about the child’s health

1. 6 Positive experience from National Health Service (NHS) 111 directing care

Most respondents gave examples of support to attend hospital. Their own knowledge and personal experience supported their decision-making process and, in some examples, they had access to specific signposting. Some respondents were encouraged and supported to attend ED by family members. Most respondents felt that ultimately COVID-19 was not a factor when their child was very unwell and when they had significant parental concern they felt safest bringing their child to hospital for paediatric review. All parents who had accessed NHS 111 were happy with the information they had received and felt reassured. Most parents had a quick response time from NHS 111 and were offered doctor callbacks which happened quickly. NHS 111 also supported appropriate transport, for parents who were not able to provide private transport.

Experience of primary care: (quotes in table 2)

Table 2.

Quotes for experience of primary care

| 2.1 Opening hours |

“I thought about walk in services…they used to do before but they have now stopped and there was nowhere I could go, so I thought to come to emergency straight away.”

“My GP’s closed, I can’t get through to my GP at all so I couldn’t tell you. I can’t get through to them at the best of times.” |

| 2.2 Access to receptionist |

“I tried calling my GP and I was very disappointed. I tried calling my GP after his first episode and I’ve not been able to get through and I reckon that’s because of COVID, I’ve not heard back for them, I left a message, nothing, and I was very disappointed with that because where are they when we need them?”

“There just needs to be better response, whatever their GP practice is, whatever they are doing, they need to change their policies in such a way, they need to be there to pick up phones as they normally are, because normally pre-COVID, if I were to call my GP I would get through, why did not get through, I called several times, where are they, they should be there” “I just can’t understand why the GP, so it’s so bloody difficult to get through to the GP, why they’re not picking up.” “So I spoke to my GP then they sent me out a link and told me to fill out a link through the GP service. But then that was a bit confusing” |

| 2.3 Being seen face to face |

“I think the GP should provide a slightly more open service. I know with the coronavirus it’s hard to go in but when a parent is describing certain symptoms, I think they should be open to looking at them”

“Seen through video and again it was quite difficult because of connection and stuff like that, and I did say to them it’s quite hard because it’s not an issue which you can talk about, it’s something that has be physically seen, it has to be physically touched…but you can’t physically see or feel those things because you’re not there. And I feel like his care would been a bit more manageable and we probably would have been managed correctly from the beginning, rather than having to have doses of antibiotics then come to A&E anyway. It would have been managed from the get go. “ “Yeah, I just don't think they should exclude completely for the face to face ones. I feel like yes there are somethings that you can manage any other phone and stuff like that but there’s other things that you definitely need to see people for. “ “Did you speak to your own GP at any point? No, because we know they don't see kids, so we didn't see the point of calling them.” “The GP just say don't come. If any cough or cold or anything ring 111 and ask their advice.” “Do you think if you had been able to see the GP in person it would have made a difference? I think they would have been able to see how bad he was.” |

| 2.4 False reassurance from primary care | “I called my GP and she said ok just sent me some pictures because this time all the appointment it was through the phone or video things like this and I sent some pictures and she said to me let’s come and see the baby the way how he looks. I go to her and she said to me that baby looks a little bit floppy and yeah in her opinion he should be seen in paediatric but just wait to see how things will go. I didn't go to the hospital, but during the night he have temperature 38°C and something and after that in the morning when I just check, his condition go down … so I decided to come to hospital. She didn't help me so much. I thought that maybe she would have helped me more honestly. But it was like an appointment for just a few minutes she just checked the baby and that’s it. Yeah it was too fast, in my opinion she didn’t pay too much attention.” |

A&E, accident and emergency; GP, general practitioner.

Most caregivers had some experience of primary care before coming to hospital. Eight caregivers had tried to access the general practitioner (GP) and all expressed difficulty, whether this was direct access to the receptionist or obtaining an appointment with their GP. One respondent who had been seen by their GP, felt falsely reassured by GP and this further delayed their access to secondary care.

Other perceived barriers: (quotes in table 3)

Table 3.

Quotes for other perceived barriers

| 3. Other perceived barriers |

“Because it’s hard for them to know over the phone. When he’s sleeping, they might not get full picture. Then we might not be able to explain properly.”

“Simply because his skin is quite complex and I think when you take pictures it doesn’t justify what is actually going on” “It’s important to see the doctor, because one thing is that what I'm saying in my English is not so good and maybe I can’t explain and maybe if I send pictures is not so visible in the pictures. And the other thing is when she see it and the way how he is and is definitely more important.” “Do you worry about your English? Yes Why does that make you worry? Because maybe it’s something which I think it might be and I can't find the correct word …the doctors when I tried to explain them they will not understand what I want to say.” |

Other significant barriers raised were digital barriers and language barriers. Some parents felt video consultations or phone consultations with photos sent by email were not appropriate, others worried about needing a phone connection to enable video calls and three parents felt language impacted on how they sought care.

Experiences of secondary care: (quotes in table 4)

Table 4.

Quotes for experiences of secondary care

| 4.1 Experiences of secondary care |

“To be fair, coming in here was really quick (the process), I didn’t need to hang around too many people. Everyone was maintaining their distance and obviously him being a child, he was put into the kids wing also immediately, which I found quite good and again I didn’t have to wait around in the waiting room, I felt the doctors and the nurses were taking that extra precautionary measure to make sure that everyone’s okay.”

“I was really worried because I’ve never seen the paediatric side of things in this hospital, but on coming in, literally as soon we entered the children’s ward it was amazing, even the A&E section was wonderful, but coming in here I’m really confident that he’s really taken care of. The nurse was there within seconds and the doctors and been very helpful in explaining to me what exactly is going on. It was different to what I expected, I think it was much better than what I expected.” “I was expecting that we would be treated kind of, sorry for my language, but kind of like an animal in a cage, if that makes sense and everyone would walk away from you scared. But not at all, I feel safer here. I feel more safe in here than I do outside.” “Was it what you expected? No, I thought I’d probably be waiting and I thought there would be massive queues” |

| 4.2 Reassured by ED set-up |

“Within a few minutes he was pulled in and put into his own little room isolated from everyone else, so that kind of reassured me that there was a low chance of him getting anything.”

“I didn’t really come in contact with other patients because in the A&E section I was in a separate room. And in here when a separate room with everything separate, which is fine.” “It was so like, so easy and they were waiting for us. It was very organised, the place like we said it was empty, we had the guidance everywhere between the seats, on the floor, like label everywhere which made things easier because I felt reassured as well.” |

| 4.3 Regret on not attending earlier |

“So I do regret not bringing him in sooner.”

“I wish I had come earlier, I wish I came a week and a half ago.” |

A&E, accident and emergency; ED, emergency department.

All but one of the respondents were happy with the care they had received in ED and the ward. For most parents there was a mismatch of expectations versus experience, their experience of secondary care exceeded their expectations and allayed their concerns. All were pleased and reassured to have a side room in the ED and the ward. They were surprised by how empty the waiting room and paediatric ED were. Some respondents also felt they would have sought care earlier had they known what their hospital experience would have been.

Advice to others following lived experience: (quotes in table 5)

Table 5.

Quotes for advice to others following lived experience

| 5. Advice to others following lived experience | “I will just say follow your instincts and not let COVID put you off, like just following your maternal instincts. If baby’s not well, if you're not feeling well, just go in and be strong and ask for things.”

“Just because of what is going around, don't compromise you child’s health.” “To look after the child health, just go ahead and go to the hospital. Don't wait. Health is more important than fear.” “I would say you absolutely must go, if you listen to your gut and listen to your instincts, don’t listen to the media and don’t listen to fear mongering news. If you feel that there is a serious enough reason for you to go into hospital, go. Don’t not go because you’re afraid of getting COVID or being exposed to it. Go, because that is your best bet of saving your life or somebody else’s life and you must go.” |

All respondents felt strongly about advice they would offer to others in similar positions, encouraging them to attend ED and not to allow the pandemic to affect their attendance.

Discussion

From interviews with caregivers we have gained an understanding of care-seeking behaviours during the pandemic: what influenced decision-making, the nature of carers’ experiences of primary and secondary care during the pandemic, the perceived barriers and facilitators to care-seeking, and what advice they would give others following their lived experience. Recommendations are outlined in box 1.

Box 1. Recommendations.

Recommendations to support decision to seek care:

Clear messaging from the government, media and hospitals themselves ‘we are here for you if you need us’

Clear messaging to the public of the infection control processes in place in hospital to protect patients

Wide distribution of Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH) traffic light decision aid for carers on when to call an ambulance, to attend general practitioner (GP), call National Health Service (NHS) 111 and when to administer self care

Focus on antenatal period to inform parents where to access health education, to improve health literacy for first time parents

Opportunistic focus on health literacy and empowerment of public, during antenatal care, health visitor visits, GP or emergency department (ED) attendance

Harness the community voice—use caregivers’ positive experiences of care to support others

Recommendations to support access to care:

Consistent and regular communications between Care Commissioning Groups and Sustainability and Transformation Partnerships, primary and secondary care

Where a caregiver’s first point of contact is primary care, there needs to be clear and consistent pathway over both the telephone and website to aid access

Use of professional interpreters with telephone services used when required

With expanding eHealth, its implementation needs to consider marginalised and vulnerable groups to ensure health equity for all

Recommendations to support informed care:

Open access between GPs and hospital, allowing for dialogue and confidence-building

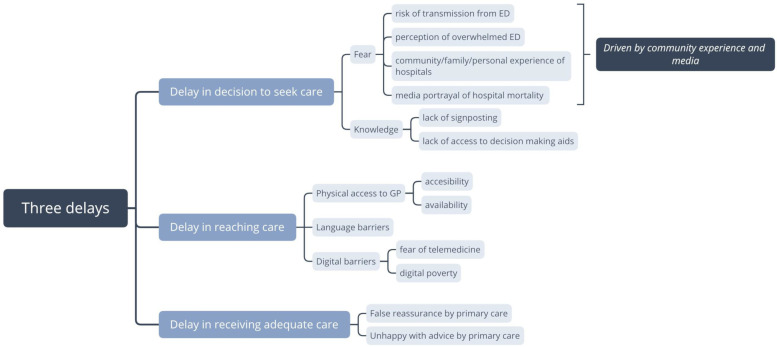

Where there were delays in care, they were in keeping with Thaddeus and Maine’s three-delay model; (1) Delay in decision to seek care, (2) Delay in reaching healthcare, (3) Delay in receiving adequate care.17 Although the model was originally designed to explore maternal death in low resource settings, it has since been used globally and here it provides a useful framework to consider barriers to care-seeking during the pandemic. Figure 1 outlines barriers identified in the three-delay framework.

Figure 1.

Barriers within the three-delay framework. ED, emergency department; GP, general practitioner.

Decision to seek care

The delay in decision to seek care was influenced predominantly by fear, which was driven by numerous sources; community perception and experience and media portrayal. Delay in decision-making was also influenced by lack of knowledge.

Given the high burden of disease in the local area at the peak of the pandemic, personal and community experience weighed heavily on fear of COVID-19 and decision-making. The media has been reported to play a significant part in perception of hospitals and ‘risk of death’ during the COVID-19 pandemic in women’s maternity care; a qualitative study evaluating perceived barriers to care for pregnant women found barriers present due to changes in the way services were delivered, virtual consultations and different perceived thresholds for seeking help.18 Where caregivers had received adequate health education and signposting to decision-making tools antenatally, they felt empowered to seek help without delay.

Caregivers often experienced confusing and conflicting situations when deciding to seek care. Barriers such as media-driven fear and GP messaging contrasted with facilitators such as support from family and friends to attend. This motivational ambivalence has been described previously.19 Caregivers are drawn in two directions with strong positive and strong negative influences, placing them in a state of ambivalence. Learning to draw on these strong positives as facilitators may help to override barriers to care-seeking.

At times, parents were caught up in the confusion of rapidly changing public health communications and the evolving situation. Almost all caregivers interviewed on reflection would advise family or friends in similar situations to seek care without hesitation, not to allow fear to delay care-seeking.

Reaching care

Delays in reaching care were focused on access to primary care, accessibility and availability of services.

Access to primary care was already a problem prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Studies show appointment availability is reflected in patient satisfaction levels, with particularly poor satisfaction in London and in areas of higher Asian ethnicity and deprivation.20 21 A recent systematic review of factors influencing decision-making around unscheduled paediatric care saw timely access to GP and satisfaction with GP services as key influencers.22

All of the eight carers who tried to access GP care for their sick children before attending hospital, expressed dissatisfaction with the service. Much of this centred on difficulty getting through to the receptionist, which reflects the huge pressure on primary care at the time. Increased resources to be dedicated to the front door of primary care are needed to allow this hard-pressed cohort of non-clinical health workers to help children access care. Many respondents felt that the challenges of telephone, video and even face-to-face consultation with the GP rendered the care inadequate to meet their child’s needs, reflecting the need to maintain face-to-face access to GP supported by specialist paediatric advice and care where needed.

Some caregivers reported language barriers, in particular, concerns they would not be understood over the phone and the importance of having their child seen face to face. Quality of care for patients whose English is not proficient can be compromised and the use of interpreters improves their experience and outcomes.23 Innovative eHealth has transformed how healthcare providers have worked during the pandemic, providing patients with vital health services while protecting them from unnecessary exposure. However, there are warnings of unintended health equity impacts from the upscaling of eHealth during the pandemic.24 Digital barriers both in access to services and appropriateness of telemedicine were highlighted by the study.

Of note, no respondents identified transport issues. If they did not have private transport, NHS 111 arranged ambulance transport in a timely fashion. Had this study been carried out earlier in the pandemic, when London Ambulance Service was extremely busy, a different theme may have been identified.

From the start of the pandemic, communications in London were centralised regionally through the Care Commissioning Groups and Sustainability and Transformation Partnerships to provide consistent information to all GPs and hospitals, with weekly email updates which were designed to give consistent messages to healthcare providers and parents. Despite this, the rapidly evolving situation meant that timely communication was challenging for all, sometimes leading to confusion.

Receiving timely and adequate care

The majority of respondents were happy with the quality of care received at the secondary care level and felt reassured by the infection control policies in the ED and on the ward. However, some caregivers were not happy with their experience in primary care and some felt they had been falsely reassured by primary care.

At a time where all healthcare workers felt vulnerable, overwhelmed and faced new challenges, there was a need for continuous communication and innovation. Local projects to work collaboratively between hospital paediatricians and primary care had positive feedback; an integrated service to provide paediatric primary care advice by paediatricians on a direct telephone line or email to local GPs allowed for ease of access for GPs. Projects similar to this had previously been held back by service-level agreements but during the pandemic, innovations were able to thrive, opening dialogue and giving confidence to GPs and in turn to caregivers.25

Study strengths

This is the first study of its kind to interview caregivers during the pandemic addressing care-seeking behaviours. The study site is a busy ED in the UK and the inpatient department serves approximately 10% of London’s population.

Study limitations

This study was carried out immediately following the peak of the pandemic where the local population had been severely hit by COVID-19; results of this study may have been different if it had been carried out in other parts of the UK. The national media attention given to the declaration of adult critical care capacity could have impacted on caregivers’ decisions to seek care at our trust rather than others. Had the study been conducted at the peak of the pandemic, results may have also differed—in particular in relation to access to NHS 111, transport and government messaging around access to care.

Although every feasible effort was made to include respondents with limited English, this was not always possible, and could have led to selection bias, in particular, given the diverse population in the local area, some of whom may suffer inequitable access to healthcare due to cultural and language barriers. Further selection bias is self-evident as only those who had sought secondary care and been admitted to hospital were included in the study. This cohort had children unwell enough to be admitted and therefore other factors, such as guilt about possible delayed presentation, may have influenced their reflections, which could have confounded the results. Due to anonymity, it was not possible to include the stage of illness at presentation, and parents’ reflections could have been altered if their child presented early or very late.

Only one caregiver was interviewed during this study whose child had presented with a mental health concern, which is insufficient to allow generalisability to others in this situation.

Triangulation would have allowed for better understanding of care-seeking behaviours from both the community perspective and also from primary care.

Conclusions

A pandemic involving a novel virus is always a challenging prospect in terms of organisation of healthcare provision. This study has highlighted parental perspectives around access to care and care-seeking behaviours which can inform us as to how to better improve service functioning during such a pandemic and beyond into the recovery period.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the participants for their contributions to interviews. The authors also thank the Northwick Park Paediatric team for their support. The authors also thank Meerat Kaur and Bina Ram of Imperial College London for their support with protocol development and methodology.

Footnotes

Contributors: GW, LP, BW, DH and MB conceived the study. GW and LP were responsible for data collection. GW, LP and BW performed data analysis. GW prepared the manuscript. All authors reviewed and contributed to manuscript revisions.

Funding: MB and DH are supported by the North-West London National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration (ARC). DH is also supported by the NIHR through the National School for Public Health Research Programme. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of any funding bodies or institutions mentioned above.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the National Research Ethics Community (IRAS 283557, REC 20/HRA2295).

References

- 1. Swann OV, Holden KA, Turtle L, et al. Clinical characteristics of children and young people admitted to hospital with covid-19 in United Kingdom: prospective multicentre observational cohort study. BMJ 2020;370:m3249. 10.1136/bmj.m3249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Boutis K, Stephens D, Lam K, et al. The impact of SARS on a tertiary care pediatric emergency department. CMAJ 2004;171:1353–8. 10.1503/cmaj.1031257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lee SY, Khang YH, Lim HK. Impact of the 2015 middle East respiratory syndrome outbreak on emergency care utilization and mortality in South Korea. Yonsei Med J 2019;60:796–803. 10.3349/ymj.2019.60.8.796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chang H-J, Huang N, Lee C-H, et al. The impact of the SARS epidemic on the utilization of medical services: SARS and the fear of SARS. Am J Public Health 2004;94:562–4. 10.2105/AJPH.94.4.562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wilhelm JA, Helleringer S. Utilization of non-Ebola health care services during Ebola outbreaks: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Glob Health 2019;9:010406. 10.7189/jogh.09.010406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wise J. Covid-19: delays in attending emergency departments may have contributed to deaths of nine children. BMJ 2020;369:m2624. 10.1136/bmj.m2624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lynn RM, Avis JL, Lenton S, et al. Delayed access to care and late presentations in children during the COVID-19 pandemic: a snapshot survey of 4075 paediatricians in the UK and ireland. Arch Dis Child 2021;106:e8. 10.1136/archdischild-2020-319848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lazzerini M, Barbi E, Apicella A, et al. Delayed access or provision of care in Italy resulting from fear of COVID-19. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2020;4:e10–11. 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30108-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cherubini V, Gohil A, Addala A, et al. Unintended consequences of coronavirus Disease-2019: remember General pediatrics. J Pediatr 2020;223:197–8. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Isba R, Edge R, Jenner R, et al. Where have all the children gone? decreases in paediatric emergency department attendances at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020. Arch Dis Child 2020;105:704.1–704. 10.1136/archdischild-2020-319385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dann L, Fitzsimons J, Gorman KM, et al. Disappearing act: COVID-19 and paediatric emergency department attendances. Arch Dis Child 2020;105:810–1. 10.1136/archdischild-2020-319654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hartnett KP, Kite-Powell A, DeVies J, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Emergency Department Visits - United States, January 1, 2019-May 30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:699–704. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6923e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Roland D, Harwood R, Bishop N, et al. Children's emergency presentations during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2020;4:e32–3. 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30206-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Goodall JW, Reed TAN, Ardissino M, et al. Risk factors for severe disease in patients admitted with COVID-19 to a hospital in London, England: a retrospective cohort study. Epidemiol Infect 2020;148:1–20. 10.1017/S0950268820002472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Arora S, Cheung CR, Sherlaw-Johnson C, et al. Use of age-specific Hospital catchment populations to investigate geographical variation in inpatient admissions for children and young people in England: retrospective, cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2018;8:e022339. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 2007;19:349–57. 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Thaddeus S, Maine D. Too far to walk: maternal mortality in context. Soc Sci Med 1994;38:1091–110. 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90226-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Karavadra B, Stockl A, Prosser-Snelling E, et al. Women's perceptions of COVID-19 and their healthcare experiences: a qualitative thematic analysis of a national survey of pregnant women in the United Kingdom. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020;20:600. 10.1186/s12884-020-03283-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Miller WB, Barber JS, Gatny HH. The effects of ambivalent fertility desires on pregnancy risk in young women in the USA. Popul Stud 2013;67:25–38. 10.1080/00324728.2012.738823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Campbell JL, Carter M, Davey A, et al. Accessing primary care: a simulated patient study. Br J Gen Pract 2013;63:e171–6. 10.3399/bjgp13X664216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kontopantelis E, Roland M, Reeves D. Patient experience of access to primary care: identification of predictors in a national patient survey. BMC Fam Pract 2010;11:61. 10.1186/1471-2296-11-61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nicholson E, McDonnell T, De Brún A, et al. Factors that influence family and parental preferences and decision making for unscheduled paediatric healthcare - systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res 2020;20:663. 10.1186/s12913-020-05527-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Flores G. The impact of medical interpreter services on the quality of health care: a systematic review. Med Care Res Rev 2005;62:255–99. 10.1177/1077558705275416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Crawford A, Serhal E. Digital Health Equity and COVID-19: The Innovation Curve Cannot Reinforce the Social Gradient of Health. J Med Internet Res 2020;22:e19361. 10.2196/19361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ferizoli V, Dharmarajah K, Pickard L. E letter response to: integrating acute services for children and young people across primary and secondary care. British Journal of General Practice 2020. https://bjgp.org/content/70/693/158/tab-e-letters [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

archdischild-2020-321260supp001.pdf (36.4KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.