We have read with interest the recent study by Qi et al.1 Currently, the impact of COVID-19 on the liver remains unexplored. Although majority of patients with COVID-19 have abnormal liver function, most studies on COVID-19 only attribute the severity of disease on the ground of respiratory complications. Thus, we aimed to perform a meta-analysis to estimate the prognosis of patients with COVID-19 stratified according to liver injury. Our meta-analysis includes nine studies2–10 with a total of 2115 patients (online supplementary file).

gutjnl-2020-322072supp001.pdf (138.6KB, pdf)

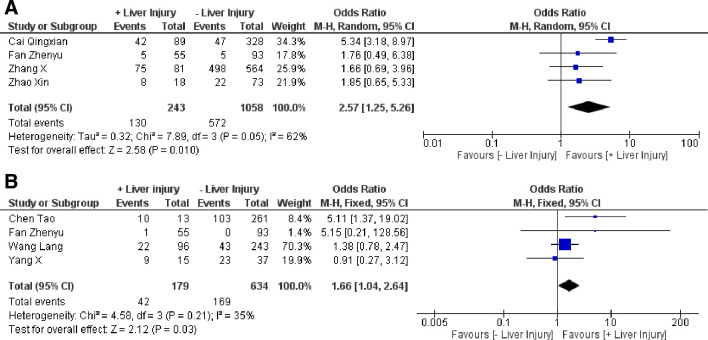

Abnormal liver function in patients with COVID-19 is possibly multifactorial; that is, drug-induced liver injury (DILI), severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 replications in the liver10 and interorgan cross-talk in acute inflammation.9 Published studies on COVID-19 have shown that 37.2%–76.3% of patients have abnormal liver function.2 9 Similarly, the prevalence of liver injury is reported in about 21.5%–45.71% of patients.2 10 Generally, 7.14%–64.15% of patients with COVID-19 had increased aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT) and bilirubin levels, whereas albumin was decreased to 27.9–33.0 g/L in non-survivor patients.6 Besides, patients with COVID-19 with chronic liver disease (CLD) might develop decompensated liver as a systemic inflammatory response induced by COVID-19.1 We found that the prevalence of CLD was 4% (95% CI 1.5 to 6.4, I2=89%) among patients with COVID-19, with cirrhosis and hepatitis B being the most common. Likewise, the incidence of liver injury was 27% (95% CI 18.2 to 35.8, I2=97%; figure 1).2–10 Of note, older patients with COVID-19 had a higher risk of liver injury (standardised mean difference (SMD): 0.81, 95% CI 0.32 to 1.29, I2=85%, p=0.001).

Figure 1.

Forest plot for the pooled prevalence of liver injury in patients with COVID-19.2–10 Ev/Trt, events/treated.

Again, most patients with COVID-19 had a noticeable reduction in CD4 and CD8 counts.9 In contrast, severe patients with COVID-19 had increased inflammatory markers like interleukin-6, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), D-dimer, ferritin, neutrophil counts and C reactive protein (CRP), suggesting a ‘cytokine storm’. Concurrently, our meta-analysis showed a significantly lower absolute lymphocyte count (SMD: −0.81, 95% CI −1.22 to −0.41, I2=62%, p<0.0001) and higher ESR (SMD: 1.65, 95% CI 0.61 to 2.70, I2=90%, p=0.002) in the liver injury group compared with the non-liver injury group. However, no remarkable difference in CRP and absolute neutrophil count was observed between the two groups.

As evidence, DILI should not be overlooked in patients with COVID-19. Cai and colleagues found that the use of lopinavir/ritonavir was significantly associated with liver injury.2 Contrarily, Fan et al did not find any difference in the prevalence of liver injury among patients with and without medication.9 Our analysis found that the liver injury group had considerably more use of lopinavir/ritonavir than the group without liver injury (OR: 4.15, 95% CI 2.36 to 7.29, I2=0%, p<0.00001). Meanwhile, insignificant difference was observed in the usage of other drugs.

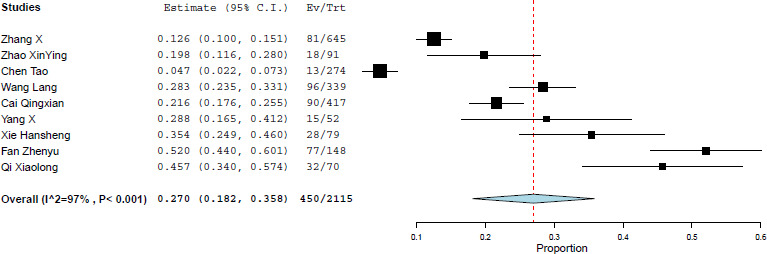

Furthermore, we also examined the prognosis of patients with COVID-19 with liver injury, and we found that patients with liver injury had obviously more severe disease (OR: 2.57, 95% CI 1.25 to 5.26, I2=62%, p=0.01) and a higher prevalence of mortality (OR: 1.66, 95% CI: 1.04 to 2.64, I2=35%, p=0.03) (figure 2).6–9 However, length of hospital stay was not significantly different among the groups (SMD: −0.61, 95% CI −2.37 to 1.15, I2=98%, p=0.50). The overall rate of severity and mortality in patients with COVID-19 with liver injury was 53.5% (130/243) and 23.5% (42/179),6–9 respectively.

Figure 2.

Forest plot for the prognosis of patients with COVID-19 with liver injury. (A) Severity.2 4 5 9 (B) Mortality.6–9

To conclude, patients with COVID-19 have a high prevalence of liver injury, and patients with COVID-19 with liver injury are at an increased risk of severity and mortality. Thus, special attention should be given to any liver dysfunction while treating patients with COVID-19.

Footnotes

Twitter: @SinghAkanand

Contributors: Concept and design: DKY, AlS, XB, WZ and TL; acquisition and interpretation of data: DKY, AkS, QZ, XB, WZ, RKY, AlS, VPA and LZ; drafting of the manuscript: DKY and AkS; critical revision of the manuscript: DKY, AlS, XB, WZ and TL; final approval: all authors.

Funding: This work was supported by grants from 973 programme (number 2014CB542101), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (number 81472212), Key Program of Medical Scientific Research Foundation of Zhejiang Province, China (number WKJ-ZJ-1410), Key Program of Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine of Zhejiang Province, China (number 2014ZZ00) and Zhejiang Provincial Program for the Cultivation of High-Level Innovative Health Talents.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Qi X, Liu Y, Wang J. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of COVID-19 patients with pre-existing cirrhosis: a multicentre cohort study. Gut 2020;69:443–6. 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-321666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cai Q, Huang D, Yu H, et al. COVID-19: abnormal liver function tests. J Hepatol 2020;S0168-8278. 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Xie H, Zhao J, Lian N, et al. Clinical characteristics of non-ICU hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 and liver injury: a retrospective study. Liver Int 2020;40:1321–6. 10.1111/liv.14449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhang X, Cai H, Hu J, et al. Epidemiological, clinical characteristics of cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection with abnormal imaging findings. Int J Infect Dis 2020;94:81–7. 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhao X-Y, Xu X-X, Yin H-S, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients with 2019 coronavirus disease in a non-Wuhan area of Hubei Province, China: a retrospective study. BMC Infect Dis 2020;20:311. 10.1186/s12879-020-05010-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chen T, Wu D, Chen H, et al. Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019: retrospective study. BMJ 2020:glaa089:m1091:m1091. 10.1136/bmj.m1091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wang L, He W, Yu X, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 in elderly patients: characteristics and prognostic factors based on 4-week follow-up. J Infect 2020;80:639–45. 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med 2020;8:475–81. 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fan Z, Chen L, Li J, et al. Clinical features of COVID-19-Related liver functional abnormality. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020;18:1561–6. 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Qi X, Liu C, Jiang Z, et al. Multicenter analysis of clinical characteristics and outcomes in patients with COVID-19 who develop liver injury. J Hepatol 2020. 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.04.010. [Epub ahead of print: 17 Apr 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

gutjnl-2020-322072supp001.pdf (138.6KB, pdf)