Abstract

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, imposing a great burden on the healthcare system. Regrettably, effective CKD therapeutic strategies are yet available due to their elusive pathogenic mechanisms. CKD is featured by progressive inflammation and fibrosis associated with immune cell dysfunction, leading to the formation of an inflammatory microenvironment, which ultimately exacerbating renal fibrosis. Transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1) is an indispensable immunoregulator promoting CKD progression by controlling the activation, proliferation, and apoptosis of immunocytes via both canonical and non-canonical pathways. More importantly, recent studies have uncovered a new mechanism of TGF-β1 for de novo generation of myofibroblast via macrophage-myofibroblast transition (MMT). This review will update the versatile roles of TGF-β signaling in the dynamics of renal immunity, a better understanding may facilitate the discovery of novel therapeutic strategies against CKD.

Keywords: transforming growth factor β, chronic kidney disease, renal inflammation, kidney fibrosis, immunity

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD), an increasing contributor to morbidity and mortality, is predicted to become the 5th most common cause of death worldwide in 2040 (1, 2). CKD can be a primary disease or a complication initiated by other disorders, including glomerulonephritis (3), hypertension (4), diabetes (5), infection (6), and genetic causes (7). Its gradual development into end-stage renal disease (ESRD) is featured by the deposition of excessive extracellular matrix (ECM) and loss of kidney function (8). Unfortunately, current treatments are ineffective because of the complicated pathophysiological mechanisms of CKD. Despite there being multiple causes, it is well-accepted that CKD is a consequence of unresolved inflammation and renal fibrosis (9–14). Importantly, increasing evidence suggests the dysregulation of renal immunity is important for CKD development (15–17), e.g., promoting inflammation by their recruitment and adhesion to the renal epithelium (11, 18) and fibrosis by their secretome induced pro-fibrogenic responses respectively (17).

Transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) consists of 3 isoforms (TGF-β1, TGF-β2 TGF-β3), TGF-β1 is well-established as an indispensable driver of renal fibrosis in the pathogenesis of CKD, while the role of TGF-β2 and TGF-β3 remains largely undefined (11, 19–21). However, direct targeting of TGF-β1 signaling would affect its physiological functions in the regulation of cell differentiation, apoptosis, and immune homeostasis (22). Consequently, disease-specific pathogenic downstream of TGF-β1 pathway has been proposed to serve as an alternative therapeutic target and prognostic marker for CKD (23, 24). Recently, emerging studies have uncovered the downstream mechanisms of TGF-β1 in both adaptive and innate immunity during CKD. Better understanding of the regulatory mechanisms of TGF-β1 signaling in renal immunity may largely facilitate the therapeutic development of CKD (25).

Importance of TGF-β1 in CKD Pathology

TGF-β1 plays an essential role in the pathogenesis of CKD due to its anti-inflammatory and fibrotic actions. TGF-β1 is well-demonstrated as an anti-inflammatory cytokine during the renal repair process at the early stage of kidney injury (26). In a mice model of crescentic glomerulonephritis, TGF-β1 inhibits the release of inflammatory cytokines as well as the infiltration of macrophages and CD3+ T cells for protecting injured kidney (27). TGF-β1 can promote the macrophages transiting from pro-inflammatory M1 into anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype (28). Nevertheless, short-term activation would facilitate the renal repair process, whereas endured activation would lead to renal fibrosis (15). Interestingly, TGF-β1 interrupts NF-κB pathway via Smad7 (29), interacts with β-catenin/Foxo complex (30), or modulates c-Jun N-terminal kinase signaling (31) to exert anti-inflammatory effect. In mice UUO and ischemic/reperfusion models, TGF-β1 also promotes β-catenin/T-cell factor (TCF) interaction, thereby simultaneously driving anti-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic responses via promoting β-catenin binding to Foxo and TCF, respectively (30, 31). Moreover, several studies further demonstrated the pro-fibrotic role of TGF-β1 signaling through mediating the ERK1/2 pathway, P38/MAPK pathway, and Akt/ERKs pathways (32, 33).

CKD would ultimately progress into end-stage renal disease (ESRD) due to the progressive fibrotic processes mediated by TGF-β1 signaling (34). TGF-β1 exerts its pro-fibrotic effects via both canonical (Smads dependent) and non-canonical (Smads independent) pathways. In the canonical pathway, Smad2 and Smad3 are two key downstream mediators of TGF-β receptor that are highly activated in renal fibrosis (35). Subsequently, activated Smad2 and Smad3 first complexed with Smad4 (36), then translocated into the nucleus to transcriptionally regulate pro-fibrotic molecules expression, including collagens, fibronectin, and alpha-smooth muscle actin (37–39), thereby facilitating fibrotic responses. However, each Smads protein is functionally distinct in the pathogenesis of CKD. Smad3 promotes while Smad2 suppresses CKD progression (40–42). Notably, Smad3 and Smad2 bind directly to the target gene, and Smad4 is lack of DNA-binding domains, but Smad4 still serve as regulators of the transcription process (43–47).

In the non-canonical pathways, TGF-β1 directly activates non-Smads signaling pathways, including MAPK pathway (48), PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway (49), TGF-β1/p38 MAPK pathway (50), ILK (51), EGFR (52), and Wnt/β-catenin pathway (53). These non-canonical pathways largely contribute to the pathogenesis of renal fibrosis, including matrix formation (54), de-differentiation of proximal tubular cells (55), cell proliferation and migration (54), and apoptosis (56).

TGF-β1 signaling is the key mechanism of ECM synthesis by inducing myofibroblasts generation from number of origins, including epithelial cells, endothelial cells, resident fibroblasts, and pericytes. Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) is a well-characterized pathological process of renal fibrosis featured by the conversion of epithelial cells into mesenchymal phenotypes. TGF-β1 signaling drives key events of EMT in vivo and in vitro, including loss of epithelial adhesion, de novo α-SMA expression, and cell migration (57, 58). During EMT, the migratory ability and mesenchymal markers, fibronectin, and α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) were acquired, while epithelium adhesion and E-cadherin protein were lost after the transition (59–61). Thus, EMT contributes to the pathogenesis of kidney fibrosis via direct generation of the collagens producing myofibroblasts (62). In the canonical pathway, Smad3 is highly activated in the UUO kidney in vivo, and TGF-β1 treated renal tubular epithelial cells in vitro, driving EMT for the myofibroblast generation and associated kidney fibrosis, which is blocked by Smad3 deletion and TGF-β1 neutralizing antibody (63–65). Non-canonical pathways, including MAPK, Rho-like GTPase, PI3K/Akt, and Wnt signaling, have been illustrated to have played emerging roles in EMT induction (28, 66, 67). TGF-β1/Smad3 signaling also drives Endothelial to Mesenchymal transitions (EndoMT), where smad3 inhibitor and endothelium-specific TGF-β receptor knockout reduces EndoMT mediated diabetic nephropathy in streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetes and tubulointerstitial fibrosis in unilateral ureteral obstruction models in vivo (68, 69). Resident fibroblasts and pericytes are rich sources of myofibroblasts, demonstrated by lineage tracing studies with P0-Cre and Foxd1-Cre to label myofibroblasts derived from fibroblasts and pericytes, respectively (70, 71). Resident fibroblasts and pericytes were activated into α-SMA+ myofibroblasts in mice model of obstructive kidney fibrosis via TGF-β1/Smad3 signaling (72–74). Therefore, TGF-β1 activates various cell types via both of the canonical and non-canonical pathways, generating myofibroblast for excess ECM deposition, ultimately contributing to fibrotic responses in CKD.

TGF-β1 in Adaptive Immunity of CKD

B Cell

Interestingly, dysregulation of humoral immunity was observed in ESRD patients; only 65% of ESRD patients can produce sufficient titer of antibodies upon vaccination, in contrast to the 95% in healthy control (16, 75). A previous study demonstrated that B1 (CD19+CD5+) and B2 lymphocytes (CD19+CD5–) are negatively associated with the progression of CKD but positively correlated with the survival of elderly CKD patients, suggesting B cell deficiency could be a prognostic factor of CKD progression (76). Autoantibodies production by B-cells is crucial for the development of IgA nephropathy and lupus nephritis. In the pathogenesis of IgA nephropathy, B-cells produce aberrant galactosylated IgA and its autoantibodies (anti-glycan antibodies) to form immune complexes, which deposition on mesangial cells to initiates glomerulonephritis and subsequent CKD progression (77–79). Similarly, in Lupus nephritis, multiple autoantibodies were involved in the immune complexes formation, including anti-dsDNA (80), anti-C1q (81), and anti-nucleosome (82) autoantibodies. Mechanistically, TGF-β suppresses B-cell maturation into antibody-producing cells, resulting in antibody abnormalities or autoantibodies production (83, 84). TGF-β1 inhibits pre-B cell proliferation via suppressing PI3K/Akt signaling and induces a cell cycle arrest of pre-B cells specifically at the G0/G1 phase (85). TGF-β1 also hinders B cell proliferation and activation indirectly via contacting the regulatory T cells, associated with the upregulation of granzyme A, granzyme B, and perforin (86). TGF-β1 induces B cell-activating factor (BAFF) production from the macrophages via Smad3/4 and PKA/CREB signaling pathways (87). BAFF is a key cytokine regulating B-cells activity, including proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and immunoglobulin secretion; excessive BAFF would suppress B-cell development resulting in autoantibodies production in IgA nephropathy and Lupus nephritis (83, 84, 88) Taken together, TGF-β1 suppress B lymphocytes development in the pathogenesis of kidney diseases via both direct and indirect mechanisms.

T Cell

T lymphocyte infiltration has been observed in CKD biopsies (89, 90) and is positively correlated with the deterioration in glomerular filtration rate (91), indicating a pathogenic role of T lymphocytes in the pathogenesis of CKD. Interestingly, CD8+ T cell abundance is significantly associated with the TGF-β1 level in the kidney biopsies of lupus nephritis (92). In a mice model of Crescentic Glomerulonephritis (GN), CD3+ T cell infiltration and associated glomerular and tubulointerstitial injuries were largely suppressed in latent TGF-β1 transgenic mice, compared with wildtype mice (93). TGF-β1 plays a crucial role in the modulation of T cell migration, activation, proliferation, and death. The recruitment and differentiation of CD4+ T cells were regulated by mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) via TGF-β1 signaling (94) while TGF-β1 enhances CD8+ T-cell activation and proliferation by switching the immune-suppressive myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) into immune-stimulating phenotype in a SMAD-2 dependent manner (95). This may explain CD8+ T-cell tubulitis and associated TGF-β1/Smad2/3 signaling activation in a rat model of aristolochic acid nephropathy (AAN) (96). In addition, TGF-β1 induces oxidative stress in injured renal tissue via mitochondrial and NADPH oxidases ROS production and suppression of antioxidant system (97–99). In Mercuric chloride intoxication and Dahl salt-sensitive rat models, elevated ROS level leading to the interstitial CD8+ T cells infiltration and associated tubular damage (100, 101). Adoptive transfer of oxidizing agents treated CD4+ T cells also caused immune complex glomerulonephritis in syngeneic recipient mice (102).

On the other hand, regulatory T cells (Tregs) play a protective role in CKD by suppressing inflammation and immune cell-mediated fibrosis (30, 103–106). Notably, abundance of peripheral Tregs is significantly reduced in CKD patients compared to the healthy controls (107). TGF-β1 is well-characterized as a Tregs inducer (108, 109). TGF-β1 has been demonstrated to increase the proliferation, differentiation, and function of Tregs by not only up-regulating Foxp3 (a master transcription regulator of Tregs) expression via PP2A pathway (110) but also suppressing IL-12R (111). Furthermore, TGF-β1 induces membrane-bound TGF-β1 on the Treg cells to suppress naive CD4+ T cells expansion for immune suppression via activating Smad3 (112). Surprisingly, Tregs are able to convert into TGF-β1-producing cells in the inflammatory environment, which markedly up-regulates the level of TGF-β1 in UUO-obstructed kidney, therefore aggravating chronic inflammation and renal fibrosis (113).

TGF-β1 in Innate Immunity of CKD

Neutrophil

Neutrophils are well-documented because of their aggravating role in inflammation (114), where neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is a popular prognostic marker for estimating the mortality of CKD patients (115). Neutrophils can initiate and amplify inflammatory responses by releasing pro-inflammatory cytokines (114, 116), and serves as a rich source of TGF-β1 in inflamed tissues (117, 118). During inflammation, TGF-β1 facilitates the accumulation of neutrophils (119, 120), therefore inhibiting TGF-β1 effectively alleviates neutrophil infiltration and inflammation (121). Furthermore, TGF-β1 signaling can be blocked by preventing Smad3 activation, which has been proposed as a potential therapeutic strategy for fibrotic diseases driven by neutrophil-mediated inflammation (122, 123).

Dendritic Cell

Dendritic cells (DCs) facilitate renal inflammation via promoting CD8+ T cell proliferation and activation during the development of CKD (124, 125). Mechanistically, TGF-β1 promotes DCs accumulation in fibrotic tissue (126) and modulates DCs-mediated proliferation and activation of T cells (127–130), contributing to the imbalance between Th17 and Treg (131) and the interleukin 17 (IL-17) release from naive CD4+ cells (132). Importantly, TGF-β1 further stimulates TGF-β1 release from DCs in an autocrine manner, serving as a major source of TGF-β1 in the tissue biopsies from stage IV–V CKD patients (133, 134) and suppressing inflammatory cytokines (IL-12, IL-18) production in DCs (135, 136). These findings suggest DCs can regulate the proliferation, activation, differentiation, and function of T cells via TGF-β1 signaling during inflammation. It has been demonstrated that targeting of DCs maybe able to suppress CKD progression by attenuating renal inflammation and fibrosis (94, 137, 138).

Macrophage

Macrophage is a key player in the pathological process of CKD that their infiltration due to their pathogenic actions in both renal inflammation and fibrosis (15, 16, 87, 89, 139, 140). It has been reported that TGF-β1 participated in macrophages-mediated immune dysfunction during the progression of CKD (15, 141, 142). TGF-β1 largely increases macrophages infiltration and accumulation in the injured kidney via stimulating the release of a potent cytokine for macrophages recruitment monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) from various types of renal cells (143–145). TGF-β1 also regulates macrophage polarization and immunomodulatory cytokines secretion. Upon the kidney injury, TGF-β1 transits M1 macrophage into regulatory M2c phenotype to facilitate kidney repair by producing the immunosuppressive and matrix remodeling activities (146–148). However, the CCL18 secreted from these CD163+ macrophages also promotes fibroblast proliferation, leading to the acceleration of kidney fibrosis (149). TGF-β1 also induces the expression of B cell-activating factor (BAFF), a key regulator of B cell activities, in macrophages via Smad3/4 dependent mechanism to influence the macrophages-mediated pathogenic function of B cells (87). The elevated plasma level of BAFF was observed in ESRD patients compared to the control group (150–152). Interestingly, the interaction between macrophages and TGF-β1 is mutual, where macrophage is the effector and a rich source of TGF-β1, actively producing and secreting TGF-β1 in inflamed kidney tissue (153, 154). Thus, blockade of TGF-β1 signaling effectively reduces macrophages infiltration (41, 155, 156) as well as significantly reduces macrophage polarization and extracellular matrix deposition (157, 158).

Novel Fibrotic Mechanism of TGF-β1: Macrophage-Myofibroblast Transition

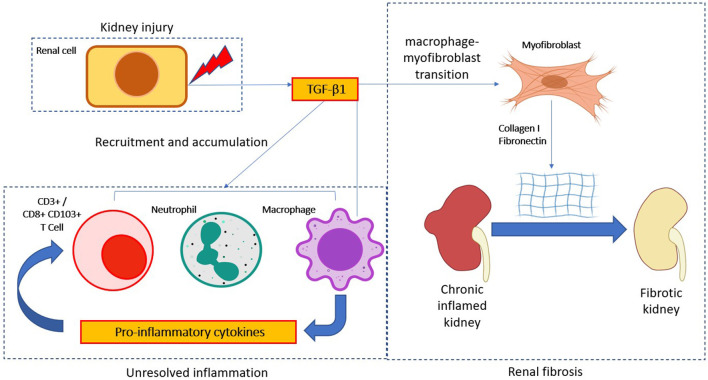

Myofibroblast is an important effector cell type that contributes to the switching of unresolved inflammation to be renal fibrosis, they featured by a high level of α-SMA expression and excessive extracellular matrix deposition (159). The sources of pathogenic myofibroblasts are highly heterogeneous and still largely unclear and controversial (160, 161). Macrophage-myofibroblast transition (MMT) is a newly-identified phenomenon driven by TGF-β1 signaling as a direct mechanism of macrophage for promoting myofibroblast generation under unresolved renal inflammation (15, 162, 163) (Figure 1). Mechanistically, TGF-β1/Smad3 signaling is suggested as the key regulator for initiating MMT during renal fibrosis in a UUO model in vivo, where TGF-β1 induces the de novo expression of myofibroblast marker α-SMA and effector collagen I in the bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDMs) via a Smad3-dependent mechanism (164). Bioinformatic analysis of TGF-β1/Smad3 dependent transcriptome of MMT in vitro further reveals Src and Pou4f1 as the pathogenic mediator in the Smad3 downstream signaling, representing a precise therapeutic target for blocking MMT (24, 165). In brief, TGF-β1/Smad3 directly activates a Src-centric gene network in BMDMs via transcriptional regulation for promoting the MMT process in the fibrosing kidney (15). More importantly, Tang et al. further discovered the importance of a neural-specific homeobox/POU domain protein Pou4f1 in the Smad3 downstream as a specific mediator for regulating MMT (24). Besides, non-canonical TGF-β1 signaling also induces MMT via β-catenin/TCF pathway, promoting pro-fibrotic gene expression in the kidney infiltrating macrophages (30, 166). Inhibitor of Src (PP1) and TCF (ICG-001) and BMDM-specific Pou4f1 silencing effectively suppress the MMT process and associated renal fibrosis, suggesting MMT may be therapeutically targeted to restrain CKD progression (24, 165).

Figure 1.

TGF-β1 in immune cell mediate CKD progression. TGF-β1 modulates immune cell activity in the progression of chronic kidney disease (CKD). After kidney injury, TGF-β1 is released by kidney cells to aid the resolution of inflammation. However, persistent TGF-β1 signaling activation would promote a chronic inflammation state via amplification of inflammatory responses. Notably, chronic TGF-β1 signaling activation would further transdifferentiate macrophage into myofibroblast to produce excessive extracellular matrix molecules (Collagen I and fibronectin), thus eventually lead to the pathogenesis of CKD.

Therapeutic Strategies for Targeting the TGF-β1-Mediated CKD

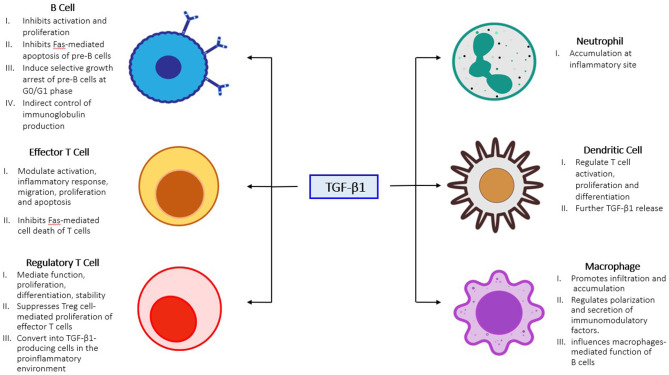

TGF-β1 signaling is essential for the progression of renal fibrosis and has been proposed as a therapeutic target for CKD (Figure 2), however systematically targeting TGF-β1 would also suppress its physiological functions and may result in adverse side effects (167, 168). Emerging clinical trials demonstrated that direct targeting TGF-β1 signaling was highly associated with adverse events in 23 to 87% of the kidney patients (167, 169, 170). Nevertheless, alternative approaches that specifically targeting the pathogenic mediators in TGF-β1 downstream may prevent the side effects. The molecular mechanism of Smad3 in renal pathology is intensively elucidated among the other Smads, genetic deletion of Smad3 effectively protected mice against collagen deposition after kidney injury (63, 171, 172). Therefore, several strategies targeting Smad3 have been investigated in a number of pre-clinical studies. Encouragingly, a Smad3 specific inhibitor SIS3 and a natural compound isolated from Poria cocos Poricoic acid effectively suppressed renal fibrosis development in experimental models of diabetic nephropathy (68), obstructive nephropathy (173), and ischemia-reperfusion injury (174) in vivo. In addition, diterpene and triterpenes (175), 25-O-methylalisol F (176), and IC-2 derivatives (177) are also capable of suppressing Smad3 activation and pro-fibrotic molecules production (Collagen I and fibronectin) in the renal epithelial cells. Importantly, emerging evidence showing macrophages mediate the therapeutic effect of Smad3 inhibition. Smad3 inhibition or genetic deletion suppressed MMT in mouse models of chronic Renal Allograft Injury (178), unilateral ureteric obstruction (164), contributed 50–60% reduction of myofibroblast population, and suppressed macrophage infiltration in type 2 diabetic nephropathy (179), thus contributing to the protective effect of Smad3 targeted therapy. Furthermore, noncoding RNAs including LRNA9884 (180), Erbb4-IR (20, 181), miR-29b (182), anti-miR-433 (183), lnc-TSI (184), and anti-miR-21 (185) were discovered from the TGF-β/Smads signaling for the obstructive and diabetic nephropathy. Among them, RNA therapies targeting LRNA9884 and miR-29b could modulate leukocytes infiltration via inflammatory cytokines expression, thus suppressing renal inflammation in diabetic nephropathy (180, 182, 186, 187). Importantly, these RNA-based therapies effectively restrained CKD progression with minimal side effects thanks to their specificity (188, 189). In addition, targeting the non-canonical TGF-β1 signaling including ERK1/2 (190, 191), β-catenin (192), p38 (193), and PI3K/Akt (49) also suppressed the pro-fibrotic actions in obstructive nephropathy, demonstrating the therapeutic potential of targeting the TGF-β1 downstream mediators (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Role of TGF-β1 in unresolved inflammation. TGF-β1 activation promotes innate immune cells accumulation (neutrophil, macrophage, and dendritic cell) at the inflammatory site, which in-turn further activate adaptive immune cells (B and T cells) and dendritic cells to amplify the inflammatory responses in chronic inflamed kidney.

Table 1.

Pre-clinical studies for the treatment of CKD by specifically targeting the downstream of TGF-β1.

| Drugs | Target | Route and effective dose | Disease model | Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canonical pathway | |||||

| SIS3 | Smad3 | I.p. 0.2, 2 mg/kg/day | UUO kidneys 1 week BALB/c male mice |

↓ Fibrosis ↓ p-Smad3/Fn/Collagen I/III ↓ Myofibroblast (α-SMA+ cells) |

(173) |

| SIS3 | Smad3 |

In vitro

1 μM I.p. 2.5, 5 μg/g SIS3 |

TGF-β1/AGEs induced Mouse pancreatic microvascular endothelial cells (MMECs) 5 Days STZ 50 μg/g induced diabetes on Tie2-Cre; Loxp-EGFP mice (C57BL/6J) |

↓ p-Smad3 ↓ RAGE-mediated EndoMT ↓ Collagen I/ α-SMA/ Fn |

(68) |

| Poricoic Acid A (PAA) | Smad3 |

In vitro

10 μM 10 mg/kg oral gavage |

TGF-β/ hypoxia/reoxygenation treated HK-2 cells Rats IRI model |

↓ p-Smad3 ↓ Collagen I/ α-SMA/ Fn |

(174) |

| IC-2 derivatives | Smad3 |

In vitro

10, 20 μM |

TGF-β1 induced Tubular epithelial cells HK-2 cells |

↓ p-Smad3 ↓ Collagen 1 |

(177) |

| 25-O-methylalisol F (MAF) | Smad3 |

In vitro

10 μM |

TGF-β1/ANG stimulated NRK-52E cells Tubular epithelial cells |

↓ p-Smad3 ↓ Wnt/β-catenin ↑ Smad7 expression ↓ Collagen I, Fn, α-SMA |

(176) |

| Diterpene (PZF) and triterpenes (PZH) | Smad3 |

In vitro

10 μM |

TGF-β1/ANGII induced Human kidney proximal epithelial cells (HK-2) Immortalized mouse podocytes (MPC5) |

↓ p-Smad3 ↓ Collagen I/ α-SMA/ Fn ↓ Wnt/ β-catenin ↓ MMP-7/PAI-1/Fsp-1 |

(175) |

| miR-29b | Smad3 | Ultrasound microbubble mediated-Mir-29b gene transfer | db/db or db/m mice AGE induced rat MC line and tubular epithelial cell line (NRK52E) |

↓ p-Smad3/ Collagen I/III ↓ Microalbuminuria ↓ Mesangial index (histological injury) |

(182) |

| Anti-miR-433 | Smad3 | Ultrasound-mediated gene transfer of inducible miR-433 shRNA | Obstructive nephropathy mouse model (UUO) Normal rat TEC line, NRK52E |

↓ Collagen I/ α-SMA/ Fn ↓ p-Smad3 |

(183) |

| lnc-TSI | Smad3 | i.v. injection of pcDNA3.1-lnc-TSI | UUO rat model TGF-β1 treated human TECs |

↓ Collagen I/ α-SMA/ Fn ↓ Kidney fibrosis (tubular interstitial fibrosis indexes/Serum creatinine) |

(184) |

| Anti-miR-21 | Smad3 | Ultrasound-mediated gene transfer of inducible miR-21 knockdown | High glucose-induced rat mesangial cell (MC) and tubular epithelial cell (TEC), NRK52E Kidneys of db/db mice |

↓ Collagen I/ IV/ Fn ↓ p-Smad3 |

(185) |

| Non-canonical pathway | |||||

| Trametinib (MEK inhibitor) | ERK1/2, mTORC1 | 3 mg/kg oral gavage | UUO mouse model | ↓α-SMA/ Vimentin ↓ p-ERK1/2, p-Akt |

(191) |

| Renalase | ERK1/2 | Adenovirus renalase gene delivery | UUO mouse model | ↓ p-ERK1/2 ↓ Collagen I/ α-SMA/ Fn |

(190) |

| QiShenYiQi (QSYQ) Traditional Chinese Medicines | β-catenin | 250, 500 mg/kg/d intra-gastric In vitro 5, 10, 20 μg/ml |

UUO rat model TGF-β treated Normal kidney proximal tubular (NRK52E) and renal fibroblast cells (NRK49F) |

↓ Collagen I/ α-SMA/ Fn ↓ β-catenin |

(192) |

| α1-adrenoceptor inhibitors | p38 | Tamsulosin (i.p.) 0.4 mg/kg/day |

UUO mouse model | ↓ Serum creatinine and urea ↓ KIM-1/NGAL/ PAL-1 ↓α-SMA/vimentin/Snai1/ Fibronectin |

(193) |

| Aloe-emodin | PI3K/Akt/mTOR | 20 mg/kg/day oral gavage |

UUO mouse model | ↓ Tubule injury index score. ↓ Masson trichromatic +ve area ↓ Collagen I/Fn ↓ Scr/BUN/urine volume |

(49) |

UUO, unilateral ureteral obstruction; EMT, epithelial-mesenchymal transition; SIS3, specific Inhibitor of Smad3; CKD, chronic kidney disease; Fn, Fibronectin; Scr, Serum creatinine; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; α-SMA, Alpha-smooth muscle actin; STZ, Streptozotocin; ANG, Angiotensin; KIM-1, Kidney Injury Molecule-1; NGAL-1, neutrophil gelatinase-associated Lipocalin; PAL-1, plasminogen activator inhibitor 1, RAGE MMP-7/PAI-1/Fsp-1.

Conclusion and Future Perspectives

TGF-β1 exerts its pathogenic roles in the progression of CKD by regulating both of the innate and adaptive immunity in the injured kidney via the canonical and non-canonical pathways including a novel fibrotic mechanism MMT. The TGF-β1 driven development of renal fibrosis from unresolved inflammation is well-observed, but underlying mechanisms remain largely unexplored. Better understanding of the underlying mechanisms of TGF-β1 pathways uncovered a number of novel pathogenic mediators from the downstream signaling, which may represent an effective therapeutic strategy to prevent renal inflammation progress into fibrosis. Moreover, the TGF-β1 regulating immune cells also contribute to other fibrotic diseases. In addition, further studies of TGF-β isoforms (TGF-β2, TGF-β3) on immune cells may reveal their therapeutic potential in renal immunity driven CKD progression. Current clinical trials targeting renal immunity shows promise, further investigation for validating the safety and effectiveness of these therapeutic approaches would discover new hope for patients with fibrotic diseases in the coming future.

Author Contributions

PT, AC, C-BZ, CG, and Y-YZ responsible for literature research and writing. K-FT, K-TL, and H-YL reviewed the manuscript and made significant revisions on the drafts. PT supervised and finalized of this work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This study was supported by Research Grants Council of Hong Kong (14106518, 14111019, 14111720); The Chinese University of Hong Kong's Faculty Innovation Award (4620528) and Direct Grant for Research (4054510).

References

- 1.Foreman KJ, Marquez N, Dolgert A, Fukutaki K, Fullman N, Mcgaughey M, et al. Forecasting life expectancy, years of life lost, and all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 250 causes of death: reference and alternative scenarios for 2016-40 for 195 countries and territories. Lancet. (2018) 392:2052–90. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31694-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peters LJF, Floege J, Biessen EA., Jankowski J, Van Der Vorst EPC. MicroRNAs in chronic kidney disease: four candidates for clinical application. Int J Mol Sci. (2020) 21:6547. 10.3390/ijms21186547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Han KH, Kim B, Ji SC, Kang HG, Cheong HI, Cho JY, et al. Mechanism of chronic kidney disease progression and novel biomarkers: a metabolomic analysis of experimental glomerulonephritis. Metabolites. (2020) 10:169. 10.3390/metabo10040169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ponticelli C, Podestà MA, Moroni G. Hyperuricemia as a trigger of immune response in hypertension and chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. (2020) 98:1149–59. 10.1016/j.kint.2020.05.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hesp AC, Schaub JA, Prasad PV, Vallon V, Laverman GD, Bjornstad P, et al. The role of renal hypoxia in the pathogenesis of diabetic kidney disease: a promising target for newer renoprotective agents including SGLT2 inhibitors? Kidney Int. (2020) 98:579–89. 10.1016/j.kint.2020.02.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ishigami J, Taliercio JT, Feldman HI, Srivastava A, Townsend RR, Cohen DL, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 and risk of hospitalization with infection in chronic kidney disease: the chronic renal insufficiency cohort (CRIC) study. J Am Soc Nephrol. (2020) 31:1836–46. 10.1681/ASN.2019101106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Groopman EE, Povysil G, Goldstein DB, Gharavi AG. Rare genetic causes of complex kidney and urological diseases. Nat Rev Nephrol. (2020) 16:641–56. 10.1038/s41581-020-0325-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meng XM, Nikolic-Paterson DJ, Lan HY. Inflammatory processes in renal fibrosis. Nat Rev Nephrol. (2014) 10:493–503. 10.1038/nrneph.2014.114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ernandez T, Mayadas TN. The changing landscape of renal inflammation. Trends Mol Med. (2016) 22:151–63. 10.1016/j.molmed.2015.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hickey FB, Martin F. Role of the immune system in diabetic kidney disease. Curr Diab Rep. (2018) 18:20. 10.1007/s11892-018-0984-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tecklenborg J, Clayton D, Siebert S, Coley SM. The role of the immune system in kidney disease. Clin Exp Immunol. (2018) 192:142–50. 10.1111/cei.13119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Toba H, Lindsey ML. Extracellular matrix roles in cardiorenal fibrosis: potential therapeutic targets for CVD and CKD in the elderly. Pharmacol Ther. (2019) 193:99–120. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2018.08.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diaz-Ricart M, Torramade-Moix S, Pascual G, Palomo M, Moreno-Castaño AB, Martinez-Sanchez J, et al. Endothelial damage, inflammation and immunity in chronic kidney disease. Toxins. (2020) 12:361. 10.3390/toxins12060361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang F, Deng L, Li J, Chen M, Liu Y, Hu Y, et al. Emodin retarded renal fibrosis through regulating HGF and TGFβ-Smad signaling pathway. Drug Des Devel Ther. (2020) 14:3567–75. 10.2147/DDDT.S245847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tang PM, Nikolic-Paterson DJ, Lan HY. Macrophages: versatile players in renal inflammation and fibrosis. Nat Rev Nephrol. (2019) 15:144–58. 10.1038/s41581-019-0110-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Espi M, Koppe L, Fouque D, Thaunat O. Chronic kidney disease-associated immune dysfunctions: impact of protein-bound uremic retention solutes on immune cells. Toxins. (2020) 12:300. 10.3390/toxins12050300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang E, Peng N, Xiao F, Hu D, Wang X, Lu L. The roles of immune cells in the pathogenesis of fibrosis. Int J Mol Sci. (2020) 21:5203. 10.3390/ijms21155203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li B, Haridas B, Jackson AR, Cortado H, Mayne N, Kohnken R, et al. Inflammation drives renal scarring in experimental pyelonephritis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. (2017) 312:F43–53. 10.1152/ajprenal.00471.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu L, Border WA, Huang Y, Noble NA. TGF-beta isoforms in renal fibrogenesis. Kidney Int. (2003) 64:844–56. 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00162.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feng M, Tang PM, Huang XR, Sun SF, You YK, Xiao J, et al. TGF-β mediates renal fibrosis via the Smad3-Erbb4-IR long noncoding RNA Axis. Mol Ther. (2018) 26:148–61. 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.09.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wei J, Wang Y, Qi X, Fan Z, Wu Y. Melatonin ameliorates hyperglycaemia-induced renal inflammation by inhibiting the activation of TLR4 and TGF-β1/Smad3 signalling pathway. Am J Transl Res. (2020) 12:1584–99. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bottinger EP, Bitzer M. TGF-beta signaling in renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. (2002) 13:2600–10. 10.1097/01.ASN.0000033611.79556.AE [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee S, Kanasaki K, Kalluri R. Circulating TGF-beta1 as a reliable biomarker for chronic kidney disease progression in the African-American population. Kidney Int. (2009) 76:10–2. 10.1038/ki.2009.130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tang PM, Zhang YY, Xiao J, Tang PC, Chung JY, Li J, et al. Neural transcription factor Pou4f1 promotes renal fibrosis via macrophage-myofibroblast transition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2020) 117:20741–52. 10.1073/pnas.1917663117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ponticelli C, Anders H. Thrombospondin immune regulation and the kidney. Nephrol Dialysis Transplantation. (2017) 32:1084–9. 10.1093/ndt/gfw431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gu YY, Liu XS, Huang XR, Yu XQ, Lan HY. Diverse role of TGF-β in kidney disease. Front Cell Dev Biol. (2020) 8:123. 10.3389/fcell.2020.00123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poveda J, Sanz A, Fernandez-Fernandez B, Carrasco S, Ruiz-Ortega M, Cannata-Ortiz P, et al. MXRA5 is a TGF-β1-regulated human protein with anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic properties. J Cell Mol Med. (2017) 21:154–64. 10.1111/jcmm.12953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang YE. Non-smad signaling pathways of the TGF-β family. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. (2017) 9:a022129. 10.1101/cshperspect.a022129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang W, Huang X, Li A, Liu F, Li J, Truong L, et al. Signaling mechanism of TGF-beta1 in prevention of renal inflammation: role of Smad7. J Am Soc Nephrol. (2005) 16:1371–83. 10.1681/ASN.2004121070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qiao X, Rao P, Zhang Y, Liu L, Pang M, Wang H, et al. Redirecting TGF-β signaling through the β-Catenin/Foxo complex prevents kidney fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. (2018) 29:557–70. 10.1681/ASN.2016121362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang Y, Feng X, Liu X, Wang Y, Hu M, Cao Q, et al. Fate alteration of bone marrow-derived macrophages ameliorates kidney fibrosis in murine model of unilateral ureteral obstruction. Nephrol Dial Transplant. (2019) 34:1657–68. 10.1093/ndt/gfy381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yi H, Huang C, Shi Y, Cao Q, Zhao Y, Zhang L, et al. Metformin attenuates folic-acid induced renal fibrosis in mice. J Cell Physiol. (2018) 233:7045–54. 10.1002/jcp.26505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhao X, Luo G, Fan Y, Ma X, Zhou J, Jiang H. ILEI is an important intermediate participating in the formation of TGF-β1-induced renal tubular EMT. Cell Biochem Funct. (2018) 36:46–55. 10.1002/cbf.3316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carew RM, Wang B, Kantharidis P. The role of EMT in renal fibrosis. Cell Tissue Res. (2012) 347:103–16. 10.1007/s00441-011-1227-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Loeffler I, Liebisch M, Allert S, Kunisch E, Kinne RW, Wolf G. FSP1-specific SMAD2 knockout in renal tubular, endothelial, and interstitial cells reduces fibrosis and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in murine STZ-induced diabetic nephropathy. Cell Tissue Res. (2018) 372:115–33. 10.1007/s00441-017-2754-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lan HY. Diverse roles of TGF-β/Smads in renal fibrosis and inflammation. Int J Biol Sci. 1(2011) 7:1056–67. 10.7150/ijbs.7.1056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang B, Komers R, Carew R, Winbanks C, Xu B, Herman-Edelstein M, et al. Suppression of microRNA-29 expression by TGF-β1 promotes collagen expression and renal fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. (2012) 23:252–65. 10.1681/ASN.2011010055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chakravarthy A, Khan L, Bensler NP, Bose P, De Carvalho DD. TGF-β-associated extracellular matrix genes link cancer-associated fibroblasts to immune evasion and immunotherapy failure. Nat Commun. (2018) 9:4692. 10.1038/s41467-018-06654-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meng P, Zhu M, Ling X, Zhou L. Wnt signaling in kidney: the initiator or terminator? J Mol Med. (2020) 98:1511–23. 10.1007/s00109-020-01978-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meng XM, Huang XR, Chung AC, Qin W, Shao X, Igarashi P, et al. Smad2 protects against TGF-beta/Smad3-mediated renal fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. (2010) 21:1477–87. 10.1681/ASN.2009121244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meng XM, Huang XR, Xiao J, Chung AC, Qin W, Chen HY, et al. Disruption of Smad4 impairs TGF-beta/Smad3 and Smad7 transcriptional regulation during renal inflammation and fibrosis in vivo and in vitro. Kidney Int. (2012) 81:266–79. 10.1038/ki.2011.327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Duan WJ, Yu X, Huang XR, Yu JW, Lan HY. Opposing roles for Smad2 and Smad3 in peritoneal fibrosis in vivo and in vitro. Am J Pathol. (2014) 184:2275–84. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2014.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dennler S, Itoh S, Vivien D, Ten Dijke P, Huet S, Gauthier JM. Direct binding of Smad3 and Smad4 to critical TGF beta-inducible elements in the promoter of human plasminogen activator inhibitor-type 1 gene. EMBO J. (1998) 17:3091–100. 10.1093/emboj/17.11.3091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen SJ, Yuan W, Mori Y, Levenson A, Trojanowska M, Varga J. Stimulation of type I collagen transcription in human skin fibroblasts by TGF-beta: involvement of Smad 3. J Invest Dermatol. (1999) 112:49–57. 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1999.00477.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Piek E, Ju WJ, Heyer J, Escalante-Alcalde D, Stewart CL, Weinstein M, et al. Functional characterization of transforming growth factor beta signaling in Smad2- and Smad3-deficient fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. (2001) 276:19945–53. 10.1074/jbc.M102382200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yuan W, Varga J. Transforming growth factor-beta repression of matrix metalloproteinase-1 in dermal fibroblasts involves Smad3. J Biol Chem. (2001) 276:38502–10. 10.1074/jbc.M107081200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shi Y, Massague J. Mechanisms of TGF-beta signaling from cell membrane to the nucleus. Cell. (2003) 113:685–700. 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00432-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Deng B, Yang W, Wang D, Cheng L, Bu L, Rao J, et al. Peptide DR8 suppresses epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition via the TGF-β/MAPK signaling pathway in renal fibrosis. Life Sci. (2020) 261:118465. 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dou F, Liu Y, Liu L, Wang J, Sun T, Mu F, et al. In Vivo Aloe-emodin ameliorates renal fibrosis via inhibiting PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway and. Rejuvenation Res. (2019) 22:218–29. 10.1089/rej.2018.2104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang S, Zhou Y, Zhang Y, He X, Zhao X, Zhao H, et al. Roscovitine attenuates renal interstitial fibrosis in diabetic mice through the TGF-β1/p38 MAPK pathway. Biomed Pharmacother. (2019) 115:108895. 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.108895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li M, Zhou H, Di J, Yang M, Jia F. ILK participates in renal interstitial fibrosis by altering the phenotype of renal tubular epithelial cells via TGF-β1/smad pathway. Eur Rev Med PharmacolSci. (2019) 23:289–96. 10.26355/eurrev_201901_16775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Patel S, Tang J, Overstreet J, Anorga S, Lian F, Arnouk A, et al. viaRac-GTPase promotes fibrotic TGF-β1 signaling and chronic kidney disease EGFR, p53, and Hippo/YAP/TAZ pathways. FASEB J. (2019) 33:9797–810. 10.1096/fj.201802489RR [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang X, Wang H, Tu Y, Li Y, Zou Y, Li G, et al. WNT1-inducible signaling protein-1 mediates TGF-β1-induced renal fibrosis in tubular epithelial cells and unilateral ureteral obstruction mouse models via autophagy. J Cell Physiol. (2020) 235:2009–22. 10.1002/jcp.29187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang S, Sun Z, Yang S, Chen B, Shi J. CTRP6 inhibits cell proliferation and ECM expression in rat mesangial cells cultured under TGF-β1. Biomed Pharmacother. (2018) 97:280–5. 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.10.091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lu Q, Wang WW, Zhang MZ, Ma ZX, Qiu XR, Shen M, et al. ROS induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition via the TGF-β1/PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway in diabetic nephropathy. Exp Ther Med. (2019) 17:835–46. 10.3892/etm.2018.7014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen J, He Q, Dai M, Kong W. HSP75 inhibits TGF-β1-induced apoptosis by targeting mitochondria in human renal proximal tubular epithelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. (2019) 515:64–71. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.05.119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yang J, Liu Y. Dissection of key events in tubular epithelial to myofibroblast transition and its implications in renal interstitial fibrosis. Am J Pathol. (2001) 159:1465–75. 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62533-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee M, Kim SH, Jhee JH, Kim TY, Choi HY, Kim HJ, et al. Microparticles derived from human erythropoietin mRNA-transfected mesenchymal stem cells inhibit epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and ameliorate renal interstitial fibrosis. Stem Cell Res Ther. (2020) 11:422. 10.1186/s13287-020-01932-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Strutz F, Okada H, Lo CW, Danoff T, Carone RL, Tomaszewski JE, et al. Identification and characterization of a fibroblast marker: FSP1. J Cell Biol. (1995) 130:393–405. 10.1083/jcb.130.2.393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Balakumar P, Alqahtani A, Khan NA, Mahadevan N, Dhanaraj SA. Mechanistic insights into hyperuricemia-associated renal abnormalities with special emphasis on epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition: pathologic implications and putative pharmacologic targets. Pharmacol Res. (2020) 105209. 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.105209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kanlaya R, Peerapen P, Nilnumkhum A, Plumworasawat S, Sueksakit K, Thongboonkerd V. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate prevents TGF-β1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition and fibrotic changes of renal cells via GSK-3β/β-catenin/Snail1 and Nrf2 pathways. J Nutr Biochem. (2020) 76:108266. 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2019.108266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu Y. New insights into epithelial-mesenchymal transition in kidney fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. (2010) 21:212–22. 10.1681/ASN.2008121226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sato M, Muragaki Y, Saika S, Roberts AB, Ooshima A. Targeted disruption of TGF-beta1/Smad3 signaling protects against renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis induced by unilateral ureteral obstruction. J Clin Invest. (2003) 112:1486–94. 10.1172/JCI200319270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li A, Zhang X, Shu M, Wu M, Wang J, Zhang J, et al. Arctigenin suppresses renal interstitial fibrosis in a rat model of obstructive nephropathy. Phytomedicine. (2017) 30:28–41. 10.1016/j.phymed.2017.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Park J, Choi H, Kim D, Kim C, Bae E, Ma S, et al. RON receptor tyrosine kinase regulates epithelial mesenchymal transition and the expression of pro-fibrotic markers via Src/Smad signaling in HK-2 and NRK49F Cells. Int J Mol Sci. (2019) 20:5489. 10.3390/ijms20215489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen KH, Hsu HH, Yang HY, Tian YC, Ko YC, Yang CW, et al. Inhibition of spleen tyrosine kinase (syk) suppresses renal fibrosis through anti-inflammatory effects and down regulation of the MAPK-p38 pathway. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. (2016) 74:135–44. 10.1016/j.biocel.2016.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liu Z, Tan R, Liu Y. The many faces of matrix metalloproteinase-7 in kidney diseases. Biomolecules. (2020) 10:960. 10.3390/biom10060960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li J, Qu X, Yao J, Caruana G, Ricardo SD, Yamamoto Y, et al. Blockade of endothelial-mesenchymal transition by a Smad3 inhibitor delays the early development of streptozotocin-induced diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes. (2010) 59:2612–24. 10.2337/db09-1631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Xavier S, Vasko R, Matsumoto K, Zullo JA, Chen R, Maizel J, et al. Curtailing endothelial TGF-beta signaling is sufficient to reduce endothelial-mesenchymal transition and fibrosis in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. (2015) 26:817–29. 10.1681/ASN.2013101137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Humphreys BD, Lin SL, Kobayashi A, Hudson TE, Nowlin BT, Bonventre JV, et al. Fate tracing reveals the pericyte and not epithelial origin of myofibroblasts in kidney fibrosis. Am J Pathol. (2010) 176:85–97. 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Asada N, Takase M, Nakamura J, Oguchi A, Asada M, Suzuki N, et al. Dysfunction of fibroblasts of extrarenal origin underlies renal fibrosis and renal anemia in mice. J Clin Invest. (2011) 121:3981–90. 10.1172/JCI57301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wu CF, Chiang WC, Lai CF, Chang FC, Chen YT, Chou YH, et al. Transforming growth factor beta-1 stimulates profibrotic epithelial signaling to activate pericyte-myofibroblast transition in obstructive kidney fibrosis. Am J Pathol. (2013) 182:118–31. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.09.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang N, Deng Y, Liu A, Shen N, Wang W, Du X, et al. Novel mechanism of the pericyte-myofibroblast transition in renal interstitial fibrosis: core fucosylation regulation. Sci Rep. (2017) 7:16914. 10.1038/s41598-017-17193-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhu Y, Yu C, Zhuang S. Protein arginine methyltransferase 1 mediates renal fibroblast activation and fibrogenesis through activation of Smad3 signaling. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. (2020) 318:F375–87. 10.1152/ajprenal.00487.2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Crosnier J, Jungers P, Courouce AM, Laplanche A, Benhamou E, Degos F, et al. Randomised placebo-controlled trial of hepatitis B surface antigen vaccine in french haemodialysis units: II, Haemodialysis patients. Lancet. (1981) 1:797–800. 10.1016/S0140-6736(81)92679-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lin J, Tang W, Liu W, Yu F, Wu Y, Fang X, et al. Decreased B1 and B2 lymphocytes are associated with mortality in elderly patients with chronic kidney diseases. Front Med. (2020) 7:75. 10.3389/fmed.2020.00075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Suzuki H, Kiryluk K, Novak J, Moldoveanu Z, Herr AB, Renfrow MB, et al. The pathophysiology of IgA nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. (2011) 22:1795–803. 10.1681/ASN.2011050464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wadei HM, Textor SC. The role of the kidney in regulating arterial blood pressure. Nat Rev Nephrol. (2012) 8:602–9. 10.1038/nrneph.2012.191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chang S, Li XK. The role of immune modulation in pathogenesis of IgA nephropathy. Front Med. (2020) 7:92. 10.3389/fmed.2020.00092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Andrejevic S, Jeremic I, Sefik-Bukilica M, Nikolic M, Stojimirovic B, Bonaci-Nikolic B. Immunoserological parameters in SLE: high-avidity anti-dsDNA detected by ELISA are the most closely associated with the disease activity. Clin Rheumatol. (2013) 32:1619–26. 10.1007/s10067-013-2330-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Seelen MA, Trouw LA, Daha MR. Diagnostic and prognostic significance of anti-C1q antibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. (2003) 12:619–24. 10.1097/00041552-200311000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bigler C, Lopez-Trascasa M, Potlukova E, Moll S, Danner D, Schaller M, et al. Antinucleosome antibodies as a marker of active proliferative lupus nephritis. Am J Kidney Dis. (2008) 51:624–9. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.10.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Shao J, Peng Y, He L, Liu H, Chen X, Peng X. Capsaicin induces high expression of BAFF and aberrantly glycosylated IgA1 of tonsillar mononuclear cells in IgA nephropathy patients. Hum Immunol. (2014) 75:1034–9. 10.1016/j.humimm.2014.08.205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ye M, Peng Y, Liu C, Yan W, Peng X, He L, et al. Vibration induces BAFF overexpression and aberrant O-Glycosylation of IgA1 in cultured human tonsillar mononuclear cells in IgA nephropathy. Biomed Res Int. (2016) 2016:9125960. 10.1155/2016/9125960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lanvin O, Guglielmi P, Fuentes V, Gouilleux-Gruart V, Mazière C, Bissac E, et al. TGF-beta1 modulates Fas (APO-1/CD95)-mediated apoptosis of human pre-B cell lines. Eur J Immunol. (2003) 33:1372–81. 10.1002/eji.200323761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Xu A, Liu Y, Chen W, Wang J, Xue Y, Huang F, et al. TGF-β-induced regulatory T cells directly suppress B cell responses through a noncytotoxic mechanism. J Immunol. (2016) 196:3631–41. 10.4049/jimmunol.1501740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kim HA, Jeon SH, Seo GY, Park JB, Kim PH. TGF-beta1 and IFN-gamma stimulate mouse macrophages to express BAFF via different signaling pathways. J Leukoc Biol. (2008) 83:1431–9. 10.1189/jlb.1007676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mackay F, Woodcock SA, Lawton P, Ambrose C, Baetscher M, Schneider P, et al. Mice transgenic for BAFF develop lymphocytic disorders along with autoimmune manifestations. J Exp Med. (1999) 190:1697–710. 10.1084/jem.190.11.1697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Giannopoulou M, Dai C, Tan X, Wen X, Michalopoulos G, Liu Y. Hepatocyte growth factor exerts its anti-inflammatory action by disrupting nuclear factor-kappaB signaling. Am J Pathol. (2008) 173:30–41. 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Chu C, Hokamp J, Cianciolo R, Dabney A, Brinkmeyer-Langford C, Lees G, et al. RNA-seq of serial kidney biopsies obtained during progression of chronic kidney disease from dogs with X-linked hereditary nephropathy. Sci Reports. (2017) 7:16776. 10.1038/s41598-017-16603-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kuo H, Huang C, Lin T, Lin C. IL-17 and CD40 ligand synergistically stimulate the chronicity of diabetic nephropathy. Nephrol Dialysis Transplantation. (2018) 33:248–56. 10.1093/ndt/gfw397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Dos Santos M, Bringhenti RN, Rodrigues PG, Do Nascimento JF, Pereira SV, Zancan R, et al. Podocyte-associated mRNA profiles in kidney tissue and in urine of patients with active lupus nephritis. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. (2015) 8:4600–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Huang XR, Chung AC, Zhou L, Wang XJ, Lan HY. Latent TGF-beta1 protects against crescentic glomerulonephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. (2008) 19:233–42. 10.1681/ASN.2007040484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Cen S, Wang P, Xie Z, Yang R, Li J, Liu Z, et al. Autophagy enhances mesenchymal stem cell-mediated CD4(+) T cell migration and differentiation through CXCL8 and TGF-β1. Stem Cell Res Ther. (2019) 10:265. 10.1186/s13287-019-1380-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Jayaraman P, Parikh F, Newton J, Hanoteau A, Rivas C, Krupar R, et al. TGF-β1 programmed myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC) acquire immune-stimulating and tumor killing activity capable of rejecting established tumors in combination with radiotherapy. Oncoimmunology. (2018) 7:e1490853. 10.1080/2162402X.2018.1490853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Pozdzik AA, Salmon IJ, Husson CP, Decaestecker C, Rogier E, Bourgeade MF, et al. Patterns of interstitial inflammation during the evolution of renal injury in experimental aristolochic acid nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. (2008) 23:2480–91. 10.1093/ndt/gfn140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Locatelli F, Canaud B, Eckardt KU, Stenvinkel P, Wanner C, Zoccali C. Oxidative stress in end-stage renal disease: an emerging threat to patient outcome. Nephrol Dial Transplant. (2003) 18:1272–80. 10.1093/ndt/gfg074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Dounousi E, Papavasiliou E, Makedou A, Ioannou K, Katopodis KP, Tselepis A, et al. Oxidative stress is progressively enhanced with advancing stages of CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. (2006) 48:752–60. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.08.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Liu RM, Desai LP. Reciprocal regulation of TGF-beta and reactive oxygen species: a perverse cycle for fibrosis. Redox Biol. (2015) 6:565–77. 10.1016/j.redox.2015.09.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.De Miguel C, Guo C, Lund H, Feng D, Mattson DL. Infiltrating T lymphocytes in the kidney increase oxidative stress and participate in the development of hypertension and renal disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. (2011) 300:F734–42. 10.1152/ajprenal.00454.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Pena C, Hernandez-Fonseca JP, Pedreanez A, Viera N, Mosquera J. Renal oxidative stress and renal CD8(+) T-cell infiltration in mercuric chloride-induced nephropathy in rats: role of angiotensin II. J Immunotoxicol. (2016) 13:324–34. 10.3109/1547691X.2015.1089960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Strickland FM, Li Y, Johnson K, Sun Z, Richardson BC. CD4(+) T cells epigenetically modified by oxidative stress cause lupus-like autoimmunity in mice. J Autoimmun. (2015) 62:75–80. 10.1016/j.jaut.2015.06.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Brinkhoff A, Sieberichs A, Engler H, Dolff S, Benson S, Korth J, et al. Pro-inflammatory Th1 and Th17 cells are suppressed during human experimental endotoxemia whereas anti-inflammatory IL-10 producing T-cells are unaffected. Front Immunol. (2018) 9:1133. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Sharma R, Kinsey GR. Regulatory T cells in acute and chronic kidney diseases. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. (2018) 314:F679–98. 10.1152/ajprenal.00236.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Do Valle Duraes F, Lafont A, Beibel M, Martin K, Darribat K, Cuttat R, et al. Immune cell landscaping reveals a protective role for regulatory T cells during kidney injury and fibrosis. JCI Insight. (2020) 5:e130651. 10.1172/jci.insight.130651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Mu Y, Zhang J, Liu Y, Ma J, Jiang D, Zhang X, et al. CD226 deficiency on regulatory T cells aggravates renal fibrosis via up-regulation of Th2 cytokines through miR-340. J Leukocyte Biol. (2020) 107:573–87. 10.1002/JLB.2MA1119-174RR [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Li Y, Liu X, Wang W, Wang S, Zhang J, Jiang S, et al. Low-dose IL-2 expands CD4(+) regulatory T cells with a suppressive function in vitro via the STAT5-dependent pathway in patients with chronic kidney diseases. Ren Fail. (2018) 40:280–8. 10.1080/0886022X.2018.1456462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Dardalhon V, Awasthi A, Kwon H, Galileos G, Gao W, Sobel RA, et al. IL-4 inhibits TGF-beta-induced Foxp3+ T cells and, together with TGF-beta, generates IL-9+ IL-10+ Foxp3(-) effector T cells. Nat Immunol. (2008) 9:1347–55. 10.1038/ni.1677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Cai J, Jiao X, Zhao S, Liang Y, Ning Y, Shi Y, et al. Transforming growth factor-β1-overexpressing mesenchymal stromal cells induced local tolerance in rat renal ischemia/reperfusion injury. Cytotherapy. (2019) 21:535–45. 10.1016/j.jcyt.2018.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Chen X, Feng L, Li S, Long D, Shan J, Li Y. TGF-β1 maintains Foxp3 expression and inhibits glycolysis in natural regulatory T cells via PP2A-mediated suppression of mTOR signaling. Immunol Lett. (2020) 226:31–7. 10.1016/j.imlet.2020.06.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Choi G, Na H, Kuen DS, Kim BS, Chung Y. Autocrine TGF-β1 Maintains the Stability of Foxp3(+) Regulatory T Cells via IL-12Rβ2 Downregulation. Biomolecules. (2020) 10:819. 10.3390/biom10060819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Zhang L, Yi H, Xia XP, Zhao Y. Transforming growth factor-beta: an important role in CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells and immune tolerance. Autoimmunity. (2006) 39:269–76. 10.1080/08916930600753903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Wu W, Tsai Y, Lin T, Wu M, Lin C. The attenuation of renal fibrosis by histone deacetylase inhibitors is associated with the plasticity of FOXP3IL-17 T cells. BMC Nephrol. (2017) 18:225. 10.1186/s12882-017-0630-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Ai Z, Udalova IA. Transcriptional regulation of neutrophil differentiation and function during inflammation. J Leukoc Biol. (2020) 107:419–30. 10.1002/JLB.1RU1219-504RR [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Woziwodzka K, Dziewierz A, Pawica M, Panek A, Krzanowski M, Gołasa P, et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio predicts long-term all-cause mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease stage 5. Folia Med Cracov. (2019) 59:55–70. 10.24425/fmc.2019.131380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Chatfield S, Thieblemont N, Witko-Sarsat V. Expanding neutrophil horizons: new concepts in inflammation. J Innate Immunity. (2018) 10:422–31. 10.1159/000493101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Haddad A, Gaudet M, Plesa M, Allakhverdi Z, Mogas AK, Audusseau S, et al. Neutrophils from severe asthmatic patients induce epithelial to mesenchymal transition in healthy bronchial epithelial cells. Respir Res. (2019) 20:234. 10.1186/s12931-019-1186-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Uyama N, Tsutsui H, Wu S, Yasuda K, Hatano E, Qin XY, et al. Anti-interleukin-6 receptor antibody treatment ameliorates postoperative adhesion formation. Sci Rep. (2019) 9:17558. 10.1038/s41598-019-54175-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Zhang S. The role of transforming growth factor beta in T helper 17 differentiation. Immunology. (2018) 155:24–35. 10.1111/imm.12938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Gao P, Tang K, Lu Y, Huang Z, Wang S, Wang M, et al. Pentraxin 3 promotes airway inflammation in experimental asthma. Respir Res. (2020) 21:237. 10.1186/s12931-020-01499-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Zhou Y, Wang T, Wang Y, Meng F, Ying M, Han R, et al. Blockade of extracellular high-mobility group box 1 attenuates inflammation-mediated damage and haze grade in mice with corneal wounds. Int Immunopharmacol. (2020) 83:106468. 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.106468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Sierra-Mondragon E, Rodríguez-Muñoz R, Namorado-Tonix C, Molina-Jijon E, Romero-Trejo D, Pedraza-Chaverri J, et al. All-trans retinoic acid attenuates fibrotic processes by downregulating TGF-β1/Smad3 in early diabetic nephropathy. Biomolecules. (2019) 9. 10.3390/biom9100525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Silva JD, Lopes-Pacheco M, De Castro LL, Kitoko JZ, Trivelin SA, Amorim NR, et al. Eicosapentaenoic acid potentiates the therapeutic effects of adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stromal cells on lung and distal organ injury in experimental sepsis. Stem Cell Res Ther. (2019) 10:264. 10.1186/s13287-019-1365-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Cao Q, Lu J, Li Q, Wang C, Wang XM, Lee VW, et al. CD103+ dendritic cells elicit CD8+ T cell responses to accelerate kidney injury in adriamycin nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. (2016) 27:1344–60. 10.1681/ASN.2015030229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Zhang F, Wang C, Wen X, Chen Y, Mao R, Cui D, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells alleviate rat diabetic nephropathy by suppressing CD103(+) DCs-mediated CD8(+) T cell responses. J Cell Mol Med. (2020) 24:5817–31. 10.1111/jcmm.15250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Chakraborty K, Chatterjee S, Bhattacharyya A. Modulation of CD11c+ lung dendritic cells in respect to TGF-beta in experimental pulmonary fibrosis. Cell Biol Int. (2017) 41:991–1000. 10.1002/cbin.10800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Lievens D, Habets KL, Robertson AK, Laouar Y, Winkels H, Rademakers T, et al. Abrogated transforming growth factor beta receptor II (TGFbetaRII) signalling in dendritic cells promotes immune reactivity of T cells resulting in enhanced atherosclerosis. Eur Heart J. (2013) 34:3717–27. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Esebanmen GE, Langridge WHR. The role of TGF-beta signaling in dendritic cell tolerance. Immunol Res. (2017) 65:987–94. 10.1007/s12026-017-8944-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Bourque J, Hawiger D. Immunomodulatory bonds of the partnership between dendritic cells and T cells. Crit Rev Immunol. (2018) 38:379–401. 10.1615/CritRevImmunol.2018026790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Morris G, Puri BK, Olive L, Carvalho AF, Berk M, Maes M. Emerging role of innate B1 cells in the pathophysiology of autoimmune and neuroimmune diseases: association with inflammation, oxidative and nitrosative stress and autoimmune responses. Pharmacol Res. (2019) 148:104408. 10.1016/j.phrs.2019.104408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Lu P, Cao Y, Wang M, Zheng P, Hou J, Zhu C, et al. Mature dendritic cells cause Th17/Treg imbalance by secreting TGF-β1 and IL-6 in the pathogenesis of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Cent Eur J Immunol. (2016) 41:143–52. 10.5114/ceji.2016.60987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Lyakh L, Trinchieri G, Provezza L, Carra G, Gerosa F. Regulation of interleukin-12/interleukin-23 production and the T-helper 17 response in humans. Immunol Rev. (2008) 226:112–31. 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00700.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Kassianos AJ, Wang X, Sampangi S, Muczynski K, Healy H, Wilkinson R. Increased tubulointerstitial recruitment of human CD141(hi) CLEC9A(+) and CD1c(+) myeloid dendritic cell subsets in renal fibrosis and chronic kidney disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. (2013) 305:F1391–1401. 10.1152/ajprenal.00318.2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Kassianos AJ, Wang X, Sampangi S, Afrin S, Wilkinson R, Healy H. Fractalkine-CX3CR1-dependent recruitment and retention of human CD1c+ myeloid dendritic cells by in vitro-activated proximal tubular epithelial cells. Kidney Int. (2015) 87:1153–63. 10.1038/ki.2014.407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Fainaru O, Shay T, Hantisteanu S, Goldenberg D, Domany E, Groner Y. TGFbeta-dependent gene expression profile during maturation of dendritic cells. Genes Immun. (2007) 8:239–44. 10.1038/sj.gene.6364380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Bonnefoy F, Couturier M, Clauzon A, Remy-Martin JP, Gaugler B, Tiberghien P, et al. TGF-beta-exposed plasmacytoid dendritic cells participate in Th17 commitment. J Immunol. (2011) 186:6157–64. 10.4049/jimmunol.1002497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Pei G, Yao Y, Yang Q, Wang M, Wang Y, Wu J, et al. Lymphangiogenesis in kidney and lymph node mediates renal inflammation and fibrosis. Sci Adv. (2019) 5:eaaw5075. 10.1126/sciadv.aaw5075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Wang R, Chen T, Wang C, Zhang Z, Wang XM, Li Q, et al. Flt3 inhibition alleviates chronic kidney disease by suppressing CD103+ dendritic cell-mediated T cell activation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. (2019) 34:1853–63. 10.1093/ndt/gfy385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Yamate J, Machida Y, Ide M, Kuwamura M, Kotani T, Sawamoto O, et al. Cisplatin-induced renal interstitial fibrosis in neonatal rats, developing as solitary nephron unit lesions. Toxicol Pathol. (2005) 33:207–17. 10.1080/01926230490523978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Tang PM, Zhang YY, Hung JS, Chung JY, Huang XR, To KF, et al. DPP4/CD32b/NF-kappaB circuit: a novel druggable target for inhibiting CRP-Driven diabetic nephropathy. Mol Ther. (2021) 29:365–75. 10.1016/j.ymthe.2020.08.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Meng XM, Nikolic-Paterson DJ, Lan HY. TGF-β: the master regulator of fibrosis. Nat Rev Nephrol. (2016) 12:325–38. 10.1038/nrneph.2016.48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Narváez A, Guiteras R, Sola A, Manonelles A, Morote J, Torras J, et al. siRNA-silencing of CD40 attenuates unilateral ureteral obstruction-induced kidney injury in mice. PLoS ONE. (2019) 14:e0215232. 10.1371/journal.pone.0215232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Lecru L, Desterke C, Grassin-Delyle S, Chatziantoniou C, Vandermeersch S, Devocelle A, et al. Cannabinoid receptor 1 is a major mediator of renal fibrosis. Kidney Int. (2015) 88:72–84. 10.1038/ki.2015.63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Zhang J, Wong MG, Wong M, Gross S, Chen J, Pollock C, et al. A cationic-independent mannose 6-phosphate receptor inhibitor (PXS64) ameliorates kidney fibrosis by inhibiting activation of transforming growth factor-β1. PLoS ONE. (2015) 10:e0116888. 10.1371/journal.pone.0116888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Zhuang C, Liu G, Barkema HW, Zhou M, Xu S, Ur Rahman S, et al. Selenomethionine suppressed TLR4/NF-κB pathway by activating selenoprotein S to alleviate ESBL Escherichia coli-induced inflammation in bovine mammary epithelial cells and macrophages. Front Microbiol. (2020) 11:1461. 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Nikolic-Paterson DJ, Wang S, Lan HY. Macrophages promote renal fibrosis through direct and indirect mechanisms. Kidney Int Suppl. (2014) 4:34–8. 10.1038/kisup.2014.7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Ikezumi Y, Suzuki T, Yamada T, Hasegawa H, Kaneko U, Hara M, et al. Alternatively activated macrophages in the pathogenesis of chronic kidney allograft injury. Pediatr Nephrol. (2015) 30:1007–17. 10.1007/s00467-014-3023-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Wang L, Ren X, Tian XF, Cheng XL, Zhao YY, Li QY, et al. Protective effects of GPR120 agonist-programmed macrophages on renal interstitial fibrosis in unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO) rats. Biomed Pharmacother. (2019) 117:109172. 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.109172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Bellon T, Martinez V, Lucendo B, Del Peso G, Castro MJ, Aroeira LS, et al. Alternative activation of macrophages in human peritoneum: implications for peritoneal fibrosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. (2011) 26:2995–3005. 10.1093/ndt/gfq771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Pahl MV, Gollapudi S, Sepassi L, Gollapudi P, Elahimehr R, Vaziri ND. Effect of end-stage renal disease on B-lymphocyte subpopulations, IL-7, BAFF and BAFF receptor expression. Nephrol Dial Transplant. (2010) 25:205–12. 10.1093/ndt/gfp397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Pieper K, Grimbacher B, Eibel H. B-cell biology and development. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2013) 131:959–71. 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.01.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Fairfax KA, Tsantikos E, Figgett WA, Vincent FB, Quah PS, Lepage M, et al. BAFF-driven autoimmunity requires CD19 expression. J Autoimmun. (2015) 62:1–10. 10.1016/j.jaut.2015.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Huen SC, Cantley LG. Macrophages in renal injury and repair. Annu Rev Physiol. (2017) 79:449–69. 10.1146/annurev-physiol-022516-034219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Meng XM, Mak TS, Lan HY. Macrophages in renal fibrosis. Adv Exp Med Biol. (2019) 1165:285–303. 10.1007/978-981-13-8871-2_13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Tarng DC, Liu IS, Lin LC, Chen NJ. Attenuation of tubular injury and renal fibrosis by TI-HU-YIN via reduction in transforming growth factor-β1 expression in unilateral ureteral obstruction mice. Chin J Physiol. (2015) 58:367–76. 10.4077/CJP.2015.BAD326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Chung S, Overstreet JM, Li Y, Wang Y, Niu A, Wang S, et al. TGF-β promotes fibrosis after severe acute kidney injury by enhancing renal macrophage infiltration. JCI Insight. (2018) 3:e123563. 10.1172/jci.insight.123563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Ren J, Li J, Feng Y, Shu B, Gui Y, Wei W, et al. Rictor/mammalian target of rapamycin complex 2 promotes macrophage activation and kidney fibrosis. J Pathol. (2017) 242:488–99. 10.1002/path.4921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Lu H, Wu L, Liu L, Ruan Q, Zhang X, Hong W, et al. Quercetin ameliorates kidney injury and fibrosis by modulating M1/M2 macrophage polarization. Biochem Pharmacol. (2018) 154:203–12. 10.1016/j.bcp.2018.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Praga M, Barrio V, Juárez GF, Luño J. Tacrolimus monotherapy in membranous nephropathy: a randomized controlled trial. Kidney Int. (2007) 71:924–30. 10.1038/sj.ki.5002215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Lebleu VS, Taduri G, O'connell J, Teng Y, Cooke VG, Woda C, et al. Origin and function of myofibroblasts in kidney fibrosis. Nat Med. (2013) 19:1047–53. 10.1038/nm.3218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Falke LL, Gholizadeh S, Goldschmeding R, Kok RJ, Nguyen TQ. Diverse origins of the myofibroblast-implications for kidney fibrosis. Nat Rev Nephrol. (2015) 11:233–44. 10.1038/nrneph.2014.246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Meng XM, Wang S, Huang XR, Yang C, Xiao J, Zhang Y, et al. Inflammatory macrophages can transdifferentiate into myofibroblasts during renal fibrosis. Cell Death Dis. (2016) 7:e2495. 10.1038/cddis.2016.402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Torres Á, Muñoz K, Nahuelpán Y, Ap RS, Mendoza P, Jara C, et al. Intraglomerular monocyte/macrophage infiltration and macrophage-myofibroblast transition during diabetic nephropathy is regulated by the A(2B) adenosine receptor. Cells. (2020) 9:1051. 10.3390/cells9041051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Wang S, Meng XM, Ng YY, Ma FY, Zhou S, Zhang Y, et al. TGF-β/Smad3 signalling regulates the transition of bone marrow-derived macrophages into myofibroblasts during tissue fibrosis. Oncotarget. (2016) 7:8809–22. 10.18632/oncotarget.6604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Tang PM, Zhou S, Li CJ, Liao J, Xiao J, Wang QM, et al. The proto-oncogene tyrosine protein kinase Src is essential for macrophage-myofibroblast transition during renal scarring. Kidney Int. (2018) 93:173–87. 10.1016/j.kint.2017.07.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Guo Y, Sun L, Xiao L, Gou R, Fang Y, Liang Y, et al. Aberrant Wnt/Beta-catenin pathway activation in dialysate-induced peritoneal fibrosis. Front Pharmacol. (2017) 8:774. 10.3389/fphar.2017.00774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Voelker J, Berg PH, Sheetz M, Duffin K, Shen T, Moser B, et al. Anti-TGF-β1 Antibody Therapy in Patients with Diabetic Nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. (2017) 28:953–62. 10.1681/ASN.2015111230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Zhao L, Zou Y, Liu F. Transforming growth factor-beta1 in diabetic kidney disease. Front Cell Dev Biol. (2020) 8:187. 10.3389/fcell.2020.00187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Vincenti F, Fervenza FC, Campbell KN, Diaz M, Gesualdo L, Nelson P, et al. A phase 2, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized study of fresolimumab in patients with steroid-resistant primary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int Rep. (2017) 2:800–10. 10.1016/j.ekir.2017.03.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Lodyga M, Hinz B. TGF-β1 - A truly transforming growth factor in fibrosis and immunity. Semin Cell Dev Biol. (2020) 101:123–39. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2019.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Fujimoto M, Maezawa Y, Yokote K, Joh K, Kobayashi K, Kawamura H, et al. Mice lacking Smad3 are protected against streptozotocin-induced diabetic glomerulopathy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. (2003) 305:1002–7. 10.1016/S0006-291X(03)00885-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Zhou L, Fu P, Huang XR, Liu F, Chung AC, Lai KN, et al. Mechanism of chronic aristolochic acid nephropathy: role of Smad3. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. (2010) 298:F1006–17. 10.1152/ajprenal.00675.2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173.Ji X, Wang H, Wu Z, Zhong X, Zhu M, Zhang Y, et al. Specific inhibitor of Smad3 (SIS3) attenuates fibrosis, apoptosis, and inflammation in unilateral ureteral obstruction kidneys by inhibition of transforming growth factor β (TGF-β)/Smad3 signaling. Med Sci Monit. (2018) 24:1633–41. 10.12659/MSM.909236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174.Chen DQ, Cao G, Zhao H, Chen L, Yang T, Wang M, et al. Combined melatonin and poricoic acid A inhibits renal fibrosis through modulating the interaction of Smad3 and β-catenin pathway in AKI-to-CKD continuum. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. (2019) 10:2040622319869116. 10.1177/2040622319869116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 175.Wang M, Chen DQ, Chen L, Liu D, Zhao H, Zhang ZH, et al. Novel RAS Inhibitors Poricoic Acid ZG and Poricoic Acid ZH Attenuate Renal Fibrosis via a Wnt/β-Catenin Pathway and Targeted Phosphorylation of smad3 Signaling. J Agric Food Chem. (2018) 66:1828–42. 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b00099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 176.Chen H, Yang T, Wang MC, Chen DQ, Yang Y, Zhao YY. Novel RAS inhibitor 25-O-methylalisol F attenuates epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and tubulo-interstitial fibrosis by selectively inhibiting TGF-β-mediated Smad3 phosphorylation. Phytomedicine. (2018) 42:207–18. 10.1016/j.phymed.2018.03.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 177.Hoi S, Tsuchiya H, Itaba N, Suzuki K, Oka H, Morimoto M, et al. WNT/β-catenin signal inhibitor IC-2-derived small-molecule compounds suppress TGF-β1-induced fibrogenic response of renal epithelial cells by inhibiting SMAD2/3 signalling. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. (2020) 47:940–6. 10.1111/1440-1681.13270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 178.Wang YY, Jiang H, Pan J, Huang XR, Wang YC, Huang HF, et al. Macrophage-to-myofibroblast transition contributes to interstitial fibrosis in chronic renal allograft injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. (2017) 28:2053–67. 10.1681/ASN.2016050573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 179.Xu BH, Sheng J, You YK, Huang XR, Ma RCW, Wang Q, et al. Deletion of Smad3 prevents renal fibrosis and inflammation in type 2 diabetic nephropathy. Metabolism. (2020) 103:154013. 10.1016/j.metabol.2019.154013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 180.Zhang YY, Tang PM, Tang PC, Xiao J, Huang XR, Yu C, et al. LRNA9884, a novel Smad3-dependent long noncoding RNA, promotes diabetic kidney injury in db/db Mice via enhancing MCP-1-dependent renal inflammation. Diabetes. (2019) 68:1485–98. 10.2337/db18-1075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 181.Sun SF, Tang PMK, Feng M, Xiao J, Huang XR, Li P, et al. Novel lncRNA Erbb4-IR Promotes Diabetic Kidney Injury in db/db Mice by Targeting miR-29b. Diabetes. (2018) 67:731–44. 10.2337/db17-0816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 182.Chen HY, Zhong X, Huang XR, Meng XM, You Y, Chung AC, et al. MicroRNA-29b inhibits diabetic nephropathy in db/db mice. Mol Ther. (2014) 22:842–53. 10.1038/mt.2013.235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 183.Li R, Chung AC, Dong Y, Yang W, Zhong X, Lan HY. The microRNA miR-433 promotes renal fibrosis by amplifying the TGF-β/Smad3-Azin1 pathway. Kidney Int. (2013) 84:1129–44. 10.1038/ki.2013.272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 184.Wang P, Luo ML, Song E, Zhou Z, Ma T, Wang J, et al. Long noncoding RNA lnc-TSI inhibits renal fibrogenesis by negatively regulating the TGF-β/Smad3 pathway. Sci Transl Med. (2018) 10:eaat2039. 10.3410/f.734198751.793554315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 185.Zhong X, Chung AC, Chen HY, Dong Y, Meng XM, Li R, et al. miR-21 is a key therapeutic target for renal injury in a mouse model of type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. (2013) 56:663–74. 10.1007/s00125-012-2804-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 186.Lv W, Booz GW, Wang Y, Fan F, Roman RJ. Inflammation and renal fibrosis: Recent developments on key signaling molecules as potential therapeutic targets. Eur J Pharmacol. (2018) 820:65–76. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2017.12.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 187.Zhang Y, Tang PM, Niu Y, Garcia Cordoba CA, Huang XR, Yu C, et al. Long Non-coding RNA LRNA9884 promotes acute kidney injury via regulating NF-kB-mediated transcriptional activation of MIF. Front Physiol. (2020) 11:590027. 10.3389/fphys.2020.590027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 188.Tang PM, Zhang YY, Lan HY. LncRNAs in TGF-beta-driven tissue fibrosis. Noncoding RNA. (2018) 4:26. 10.3390/ncrna4040026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 189.Tang PM, Zhang YY, Mak TS, Tang PC, Huang XR, Lan HY. Transforming growth factor-beta signalling in renal fibrosis: from Smads to non-coding RNAs. J Physiol. (2018) 596:3493–503. 10.1113/JP274492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]