Abstract

Vacuoles are acidic organelles that store FeIII polyphosphate, participate in iron homeostasis, and have been proposed to deliver iron to mitochondria for iron–sulfur cluster (ISC) and heme biosynthesis. Vma2Δ cells have dysfunctional V-ATPases, rendering their vacuoles nonacidic. These cells have mitochondria that are iron-dysregulated, suggesting disruption of a putative vacuole-to-mitochondria iron trafficking pathway. To investigate this potential pathway, we examined the iron content of a vma2Δ mutant derived from W303 cells using Mössbauer and EPR spectroscopies and liquid chromatography interfaced with inductively-coupled-plasma mass spectrometry. Relative to WT cells, vma2Δ cells contained WT concentrations of iron but nonheme FeII dominated the iron content of fermenting and respiring vma2Δ cells, indicating that the vacuolar FeIII ions present in WT cells had been reduced. However, vma2Δ cells synthesized WT levels of ISCs/hemes and had normal aconitase activity. The iron content of vma2Δ mitochondria was similar to WT, all suggesting that iron delivery to mitochondria was not disrupted. Chromatograms of cytosolic flow–through solutions exhibited iron species with apparent masses of 600 and 800 Da for WT and vma2∆, respectively. Mutant cells contained high copper concentrations and high concentrations of a species assigned to metallothionein, indicating copper dysregulation. vma2Δ cells from previously studied strain BY4741 exhibited iron-associated properties more consistent with prior studies, suggesting subtle strain differences. Vacuoles with functional V-ATPases appear unnecessary in W303 cells for iron to enter mitochondria and be used in ISC/heme biosynthesis; thus, there appears to be no direct or dedicated vacuole-to-mitochondria iron trafficking pathway. The vma2Δ phenotype may arise from alterations in trafficking of iron directly from cytosol to mitochondria.

Keywords: V-ATPase, W303, BY4741, EPR, Cup1, homeostasis, iron–sulfur clusters, labile iron pool, labile copper pool, respiratory shield

Abbreviations: CD, central quadrupole doublet; FTS, flow-through solution; ISC, iron sulfur cluster; LC-ICP-MS, liquid chromatography interfaced with inductively-coupled-plasma mass spectrometry; LMM, low-molecular-mass; MB, Mössbauer; NHHS, nonheme high spin; ROS, reactive oxygen species; WT, wild type; YPAD, yeast extract peptone adenine dextrose medium

Vacuoles are acidic organelles in fungi and plants that are evolutionarily connected to endosomes and lysosomes in humans. Their acidity is essential for sequestering and storing iron and for participating in cellular iron homeostasis (1, 2). The vacuolar ATPase (V-ATPase) is a membrane-bound multisubunit complex that pumps protons from the cytosol into the vacuole. This results in an acidic vacuolar lumen (pH 5.6–6.1) and a slightly basic cytosol (pH ∼ 7.4) (3, 4, 5, 6, 7). vma-mutant cells lack functional V-ATPases and grow well only in media buffered between pH 3 and 6, a narrower and more acidic range than is normal for WT cells (7, 8, 9). The pH of the growth medium influences the pH of vacuoles (8). When vma-mutant cells were grown at pH 5.5, their vacuolar pH was 5.9 (4, 6, 7). When the same cells were transferred to pH 7.5 medium, vacuolar pH shifted to 7.05. In contrast, vacuoles of WT cells treated equivalently remained at pH 5.9.

V-ATPases consist of two subcomplexes including a peripheral membrane subcomplex V1 and an integral membrane complex Vo. In yeast, V-ATPases are found in vacuolar membranes or vacuole–mitochondria contact sites. Inactivation or deletion of any component subunit leads to a similar mutant phenotype characterized by reduced replicative lifespan, decreased inorganic polyphosphates, sensitivity to oxidative stress, and iron dysregulation. VMA2 encodes subunit B of the V1 subcomplex; the knockout is viable although it lacks V-ATPase activity.

Iron-replete WT vacuoles contain high (mM) concentrations of polyphosphate that coordinate FeIII ions (10, 11, 12). Polyphosphate chains are synthesized by the VTC complex on the vacuolar membrane (13, 14), a process that depends on the proton gradient generated by V-ATPase. Without this gradient, vma mutants are deficient in polyphosphate ions and are less able to store iron (15, 16). Thus, polyphosphate ions and protons both impact vacuolar iron metabolism.

Iron homeostasis in yeast involves about two dozen genes called the iron regulon (17). These genes are activated when mitochondrial iron–sulfur cluster (ISC) assembly is compromised (18). For example, this condition is evident in strains that are deficient in yeast frataxin homolog 1 (Yfh1) (19), yeast adrenodoxin homolog 1 (Yah1) (20), and the inner membrane transporter Atm1 (21). These cells respond to iron regulon activation by importing excess iron and mobilizing vacuolar iron stores.

The iron regulon is activated in vma2Δ cells grown in iron-replete (μM range) media even though their mitochondria are not deficient in proteins involved in ISC assembly (22, 23). This implies that mitochondria cannot assemble sufficient ISCs when the vacuolar lumen is insufficiently acidic, and it highlights an intriguing connection between the two organelles. vma2Δ cells have reduced activities of mitochondrial ISC-containing proteins that are involved in respiration, including aconitase, succinate dehydrogenase, and the Rieske iron–sulfur protein (23). vma-mutant cells grow poorly on respiring media (3, 22, 24, 25). However, supplementing growth media with mM concentrations of iron a) rescues this phenotype, b) deactivates the iron regulon (22, 23), c) increases the activity of ISC-containing enzymes, d) increases the rate of O2 consumption, and e) stimulates respiration (24, 25, 26).

Excess supplemented iron provides the additional iron needed for the biosynthesis of iron-rich mitochondria which are in turn needed for respiration. This requirement is uncompromising, even in WT cells, such that cells grown on iron-deficient minimal medium (MM) succumb to autophagy so that they can recycle sufficient cellular iron for use in mitochondriogenesis (27). During autophagy, Smf3 and Fet5/Fth1 iron exporters on the vacuolar membrane pump iron into the cytosol to satisfy mitochondrial demand. Iron-deficient vma mutants have difficulty undergoing autophagy which hinders respiration (27).

When the iron regulon is activated in ISC-mutant cells, the rate of cellular iron import increases dramatically owing to expression of a high-affinity iron importer (composed of Fet3 and Ftr1) on the plasma membrane. Expression of the high-affinity vacuolar iron exporter (composed of Fet5 and Fth1) also increases. Fet3 and Fet5 are paralogous multicopper oxidases controlled by the iron regulon. As a result, the vacuoles of ISC-mutant cells are nearly devoid of iron, and much of the excess iron that flows into the cytosol ultimately accumulates in mitochondria as FeIII oxyhydroxide phosphate–associated nanoparticles (19, 20, 21).

vma-mutant cells have difficulty importing extracellular iron because copper-containing Fet3 has difficulty maturing (i.e., metallating with copper) in the Golgi (1, 28). Whether these cells also have difficulty exporting vacuolar iron is unknown, but this seems likely, given the similarities between Fet3 and Fet5. In any event, the concentration of iron in vma-mutant cells is not excessive relative to WT cells even though the iron regulon is activated. vma2Δ cells reportedly contain only ∼30% more iron than WT cells (23). In contrast, ISC mutants contain an order-of-magnitude more iron than WT cells.

The mechanism by which a decline in the acidity of vacuoles causes a decline of mitochondrial function, and how excessive iron rescues this decline, has been investigated by Kane (23) and more recently by Hughes (26). Both hypothesize that the flow of iron from vacuoles to mitochondria is disrupted in vma-mutant cells and that excess media iron re-establishes this pathway. Besides sequestering iron, vacuoles store amino acids, including cysteine (29). Hughes et al. (26) found that loss of vacuolar acidity increases nonvacuolar pools of cysteine and other amino acids. One intriguing possibility is that excess cysteine in the cytosol binds iron, thereby blocking import into mitochondria.

vma mutants generate high levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and are hypersensitive to oxidative stress (5, 22, 30, 31). They are more easily intoxicated by high levels of transition metals than WT cells. This likely occurs because vma cells have difficulty storing metals in their vacuoles, which otherwise imparts metal resistance to the cell (17, 22, 24, 32, 33). Surprisingly, mitochondrial respiration is not the major source of ROS in vma2Δ cells (22). Rather, excessive ROS is likely associated with iron dyshomeostasis and increased Fenton chemistry (5, 23).

Also surprising is that the relationship between vacuolar acidity, cellular iron, mitochondrial function, and ROS damage is related to human aging and longevity. Hughes and Gottschling found that a decline of vacuolar acidity is associated with age-related deterioration of mitochondria (34). Overexpressing V-ATPase subunits suppresses mitochondrial dysfunction in aging cells by hyperacidifying vacuoles. Young yeast cells treated with a V-ATPase inhibitor and mutant cells lacking V-ATPase subunits both have impaired mitochondrial morphology similar to the organelle in aged cells (34).

The objective of the current study was to better understand the connection between vacuolar acidity, mitochondrial function, and iron homeostasis by using powerful biophysical and bioanalytical probes, namely Mössbauer (MB) and EPR spectroscopies and liquid chromatography interfaced with inductively-coupled-plasma mass spectrometry (LC-ICP-MS). Mitochondria, vacuoles, and the cytosol of vma2Δ cells were isolated and investigated. Our results confirm and extend some but not all relevant previous results, with differences probably due to the background strains and media/conditions used. New insights into the connection between vacuoles and mitochondria are presented, highlighting the potential importance of low-molecular-mass (LMM) iron, copper, and sulfur species in the cytosol of these yeast cells.

Results

A haploid VMA2 deletion strain was generated from a W303 parent to allow for direct comparison to previous biophysical studies that used the same genetic background (10, 11, 20, 21, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39). We refer to W303 and the mutant strain as WT and vma2ΔW, respectively. We initially investigated whether the iron content of these two strains differed and whether the pH of the medium influenced that content. WT and vma2ΔW cells were grown in MM containing 2% glucose as the carbon source (fermentation) and supplemented with iron (typically 40 μM 57FeIII citrate). Medium pH was buffered using citric acid and sodium citrate. Under these conditions, vma2ΔW cells grew well at pH values 3, 4, and 5 although growth was inhibited when the medium pH was 6 or 7; in contrast, WT cells grew well in media buffered from pH 3 to 7.

Whole-cell iron concentrations (Table 1) revealed no obvious pH dependence; however, some strain-dependent trends were evident. vma2ΔW cells contained 30% less iron, 60% less phosphorus, 6× less manganese, 4× less zinc, and 2.5× more copper than WT cells. The increased copper when considered with previous reports that Fet3 in vma2Δ cells is not metallated in the Golgi (1, 28) suggested that copper was dysregulated in these mutant cells and that vma2Δ cells compensated by importing excessive copper.

Table 1.

Metal concentrations in WT and Vma2ΔW whole cells and cytosol fractions

| Sample | n | Fe | Cu | Mn | Zn | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT pH 7 | 3 | 200 ± 30 | 100 ± 40 | 27 ± 8 | 500 ± 200 | 190 ± 10 |

| WT pH 6 | 4 | 320 ± 40 | 100 ± 100 | 31 ± 3 | 1300 ± 500 | 500 ± 100 |

| WT pH 5 | 4 | 300 ± 40 | 78 ± 5 | 60 ± 20 | 900 ± 100 | 500 ± 100 |

| WT pH 4 | 3 | 260 ± 20 | 150 ± 10 | 44 ± 2 | 470 ± 60 | 280 ± 20 |

| WT pH 3 | 4 | 190 ± 40 | 130 ± 10 | 18 ± 6 | 840 ± 40 | 210 ± 30 |

| vma2Δw pH 5 | 4 | 250 ± 40 | 240 ± 50 | 10 ± 1 | 193 ± 6 | 170 ± 40 |

| vma2Δw pH 4 | 2 | 128 ± 3 | 220 ± 20 | 7 ± 4 | 130 ± 20 | 67 ± 9 |

| vma2Δw pH 3 | 5 | 160 ± 40 | 340 ± 40 | 2 ± 1 | 230 ± 20 | 104 ± 7 |

| WT cytosol | 2 | 270 ± 50 | 100 ± 7 | 25 ± 1 | 800 ± 100 | 490 ± 40 |

| vma2Δw cytosol | 4 | 200 ± 70 | 280 ± 70 | 8 ± 2 | 250 ± 80 | 170 ± 10 |

| WT cytosol (1 μM Fe) | 2 | 230 ± 20 | 130 ± 20 | 11 ± 3 | 340 ± 40 | 300 ± 30 |

| WT FTS (1 μM Fe) | 2 | 66 ± 2 | 13 ± 4 | 7 ± 2 | 130 ± 20 | 170 ± 6 |

Cells were grown on MM supplemented with 40 μM iron citrate (unless specified otherwise) and 10 μM CuSO4. Samples were whole cells unless otherwise indicated. n, number of independent replicates. Concentrations are in μM except for P which is in mM. Reported cytosol and FTS concentrations are measured values after being multiplied by a 14× dilution factor.

FTS, flow-through solution; MM, minimal medium.

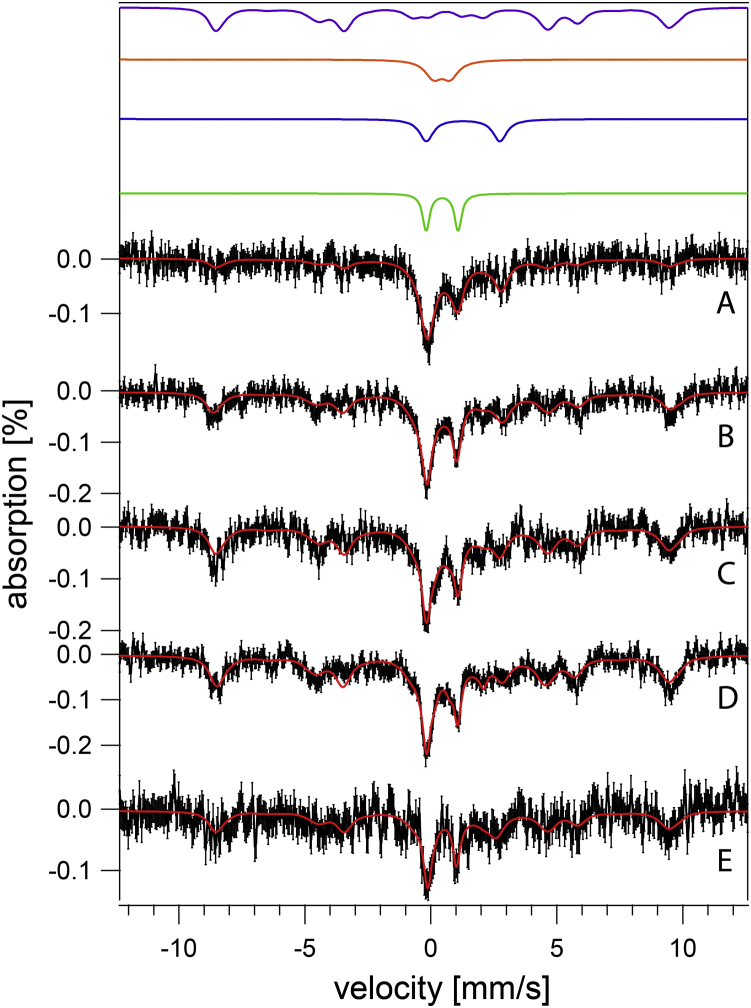

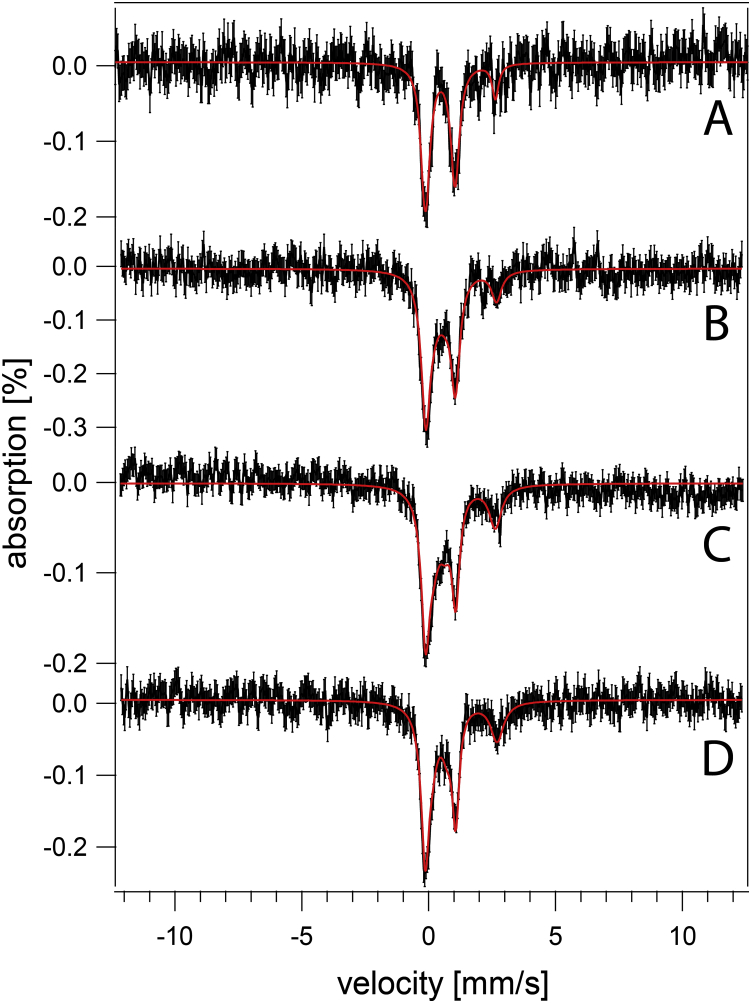

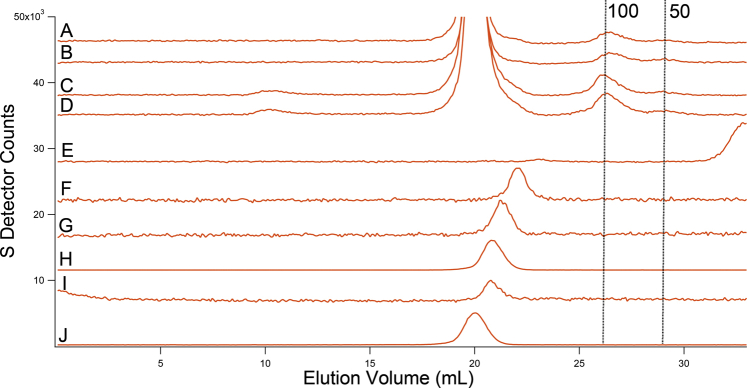

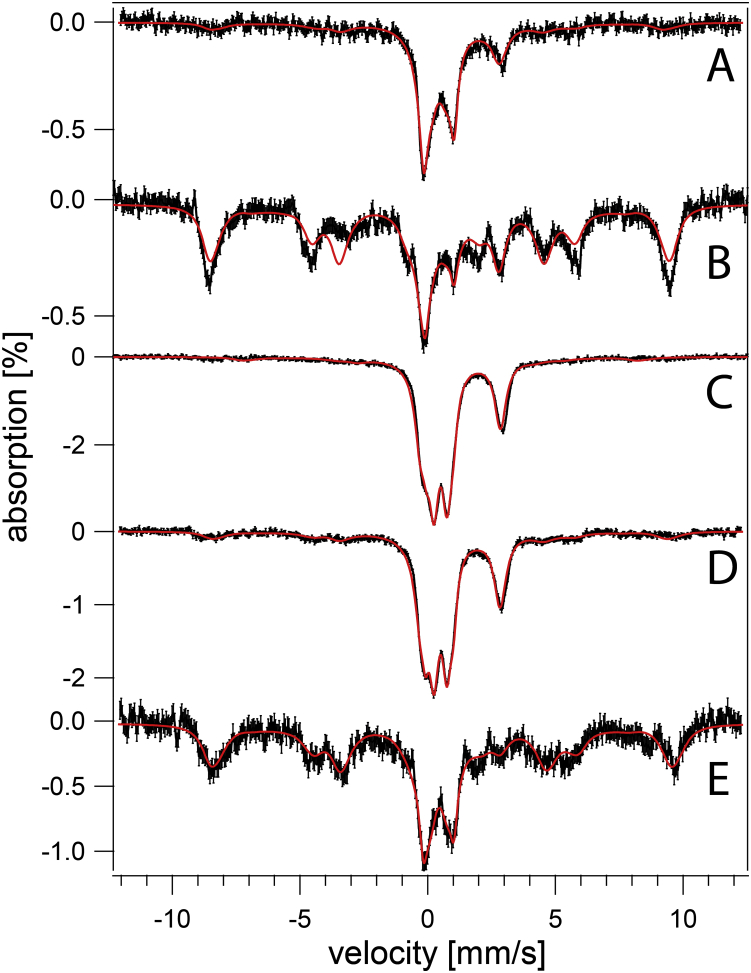

MB spectra of both strains were collected to investigate the type of iron present. WT cells exhibited qualitatively similar spectra regardless of pH (Fig. 1), but some subtle pH-dependent trends were evident. At low pH, over 60% of spectral intensity was a magnetic feature originating from nonheme high-spin (NHHS) FeIII. The solid purple line in Figure 1 is a simulation using parameters in Table S1. The FeIII ions are coordinated to anionic polyphosphate chains in vacuoles (10, 11). With increasing pH, the percentage of cellular iron in this form declined to ∼30% at pH 7. We conclude that WT vacuoles store less iron as medium pH increases.

Figure 1.

Mössbauer spectra of fermenting WT cells at varying pH (MM supplemented with 40 μM57FeIIIcitrate and 10 μM CuSO4).A, pH 7, B, pH 6, C, pH 5, D, pH 4, E, pH 3. Data are black hashmarks; composite simulations are the solid red lines. The green line simulates low-spin FeII hemes and [Fe4S4]2+ clusters. The blue line simulates nonheme high-spin FeII. The purple line simulates nonheme high-spin FeIII. Individual simulations were combined to yield the composite simulation of of the WT pH 5 spectrum. MM, minimal medium.

Also evident in WT MB spectra was the central doublet (CD) with isomer shift and quadrupole splitting parameters typical of [Fe4S4]2+ clusters and low-spin FeII hemes (simulated by the green line in Fig. 1). MB spectra of isolated mitochondria are dominated by the CD (36, 37, 38), which originates mainly from iron-rich respiratory complexes and respiration-related iron-containing proteins, e.g., aconitase. A substantial portion of the CD intensity in whole cells is due to cytosolic [Fe4S4]2+-containing proteins. Percentagewise, the spectral intensity of the CD in whole-cell WT spectra increased from ∼15% at low pH values to ∼30% at pH 7. This increase likely arose from the percentagewise decrease of vacuolar iron, such that the absolute concentration of the [Fe4S4]2+ clusters and LS FeII hemes that give rise to this spectral feature were fairly constant with changes in pH.

Another ∼20% of the intensity of WT cell spectra was a quadrupole doublet (simulated by the blue line in Fig. 1) with parameters typical of NHHS FeII complexes coordinated by 5 to 6 O/N donors (δ = 1.27 mm/s; ΔEQ = 2.9 mm/s). Such species are probably located in the cytosol and mitochondria, among other regions of the cell. Another ∼10% of spectral intensity consisted of poorly resolved material near the center of the spectrum (at ∼ 0 velocity). In Figure 1, this material was simulated (orange line) assuming parameters of FeIII phosphate–associated nanoparticles. Apart from the modest decline of vacuolar iron with increased pH, the iron in WT cells generally remained invariant over four orders-of-magnitude of acidity in the growth media. This implies that intracellular pH of WT cells is well regulated against extracellular perturbations, probably due to the activities of proton pumps on the plasma and vacuolar membranes.

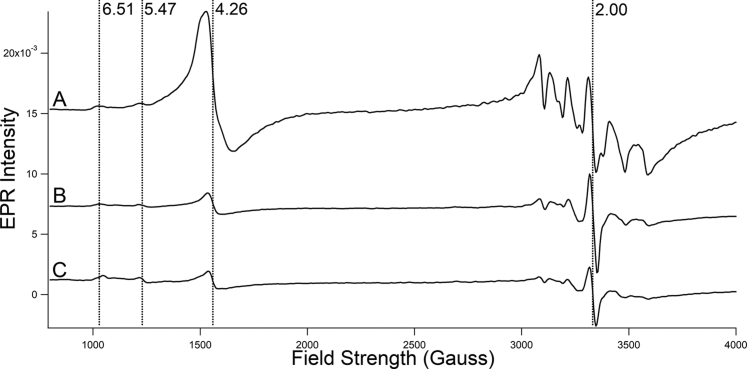

The WT EPR spectrum of whole WT cells cultured at pH 5 with 40 μM supplemented FeIII citrate (Fig. 2A) exhibited signals similar to those observed previously (11, 38). Vacuolar FeIII exhibited a prominent g = 4.3 signal. Features at g = 6.5 and 5.5 are typical of high-spin FeIII hemes. A hyperfine-split signal arising from MnII ions was observed at g = 2.00, as was an isotropic radical signal. No signals attributable to CuII ions were observed.

Figure 2.

EPR spectra of fermenting WT and vma2ΔWwhole cells.A, WT; B–C, independent replicates of vma2Δw. Spectra were collected at 10 K; other conditions are given in Experimental procedures.

MB spectra of vma2ΔW cells grown in MM at pH 3, 4, and 5 were dominated by an FeII quadrupole doublet (Fig. 3) that accounted for ∼60% of spectral intensity. The high-energy line of the CD was also evident as a partially resolved shoulder on the low-energy line of the dominating FeII doublet at ∼ + 1 mm/s. Like WT cells, the iron content of vma2ΔW cells was generally invariant in media in which acidity varied by three orders of magnitude. We had predicted that the magnetic feature due to vacuolar FeIII in MB spectra of WT cells would also be present in spectra of vma2ΔW cells grown at pH 3 or 4, given that the acidity of vacuoles lacking functional V-ATPase is affected by the pH of the growth media. This prediction was not realized, possibly for reasons discussed below.

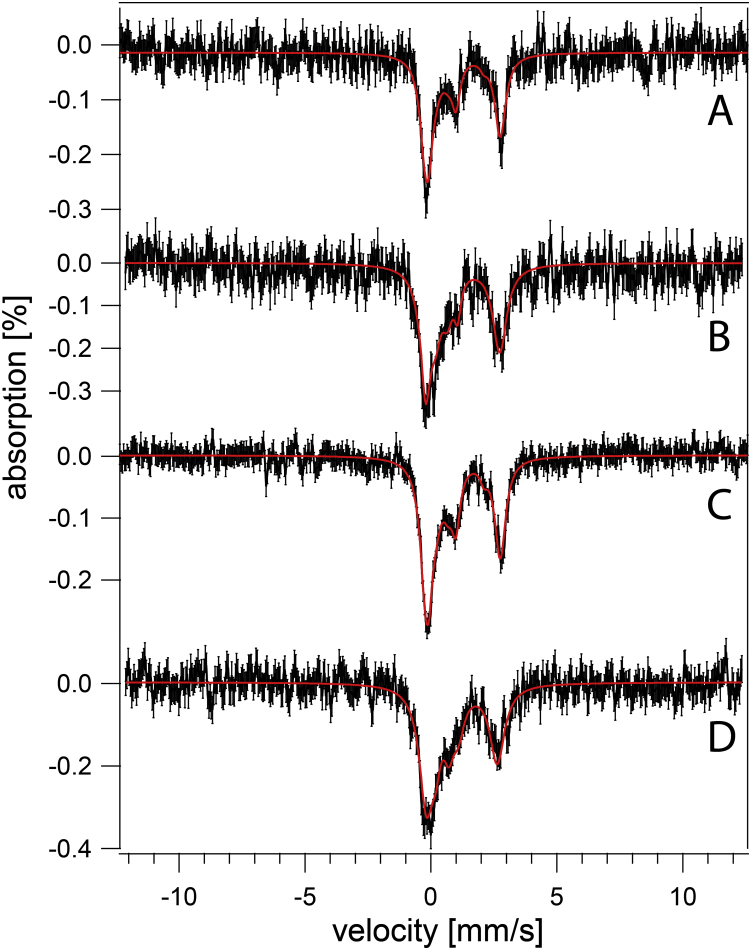

Figure 3.

Mössbauer spectra of vma2Δ cells at varying pH (MM supplemented with 40 μM ferric citrate and 10 μM copper sulfate).A, pH 5, B, pH 5 with 1 mM supplemented cysteine, C, pH 4, D, pH 3. Black, collected spectrum. Red, composite simulation. MM, minimal medium.

The CD represented ∼20% of the spectral intensity for vma2ΔW cells at each pH within this range. Assuming an average cellular iron concentration of 180 μM (Table 1) suggests that ∼40 μM iron in these cells arose from [Fe4S4]2+ clusters and LS FeII hemes. For WT cells, with an average iron concentration of ∼250 μM and ∼20% CD intensity, the corresponding concentration would be ∼50 μM. The two concentrations are the same within our uncertainties. We had expected that the concentration of such centers in vma2ΔW cells would have been much lower and that most of the iron in these cells would have been FeIII phosphate–associated nanoparticles as is observed in other ISC-mutant cells in which the iron regulon is activated. However, MB spectra of vma2ΔW cells did not exhibit intense features typical of nanoparticles nor did they provide clear evidence that the iron regulon was activated.

EPR spectra of vma2ΔW cells at pH 5 (Fig. 2, B–C) supported the MB spectra and provided new insights. The intensity of the g = 4.3 signal due to vacuolar FeIII was strongly reduced relative to in WT spectra, consistent with the absence of the magnetic feature due to vacuolar FeIII in corresponding MB spectra. Minor features attributed to high-spin hemes at g = 6.5 and 5.5 were comparable in intensity to those of WT, suggesting normal levels of cellular hemes in the mutant cells. The hyperfine-split signal due to MnII ions was dramatically reduced in vma2ΔW EPR spectra, consistent with the 6-fold decline of Mn concentration relative to in WT cells (Table 1). No signals attributable to S = ½ CuII ions were observed, despite the 2.5-fold increase in Cu concentration in the mutant cells. This suggests that the additional Cu ions in vma2ΔW cells were in the reduced diamagnetic CuI state.

We assessed whether the dominating FeII species in vma2ΔW cells arose from an accumulation of LMM iron complexes in the cytosol. The cytosol was isolated from WT and vma2ΔW cells, and the concentration of iron in these cytosol isolates was determined (Table 1). The iron concentration of cytosol from both strains was high (200, 270 μM), similar to values reported previously (38). Cytosol solutions were passed through a 10-kDa cutoff membrane, and the metal contents of flow-through solutions (FTSs) were also determined. We previously found that LMM iron species constituted ca. 70% of cytosolic iron at 40 μM iron supplementation (38). Here, we observed that ∼30% of cytosolic iron from cells grown with 1 μM Fe was present in an LMM form (Table 1). The concentration of LMM iron in the cytosol was higher than expected by an order-of-magnitude. We suspected that iron-rich vacuoles may have burst during cytosol isolation and metals from the ruptured organelles leached into the cytosol. However, vacuoles contain little iron at 1 μM iron supplementation (37, 38), yet the iron concentrations of cytosol isolated from 1 μM and 40 μM iron-supplemented WT cells were similar. Thus, vacuole-bursting seems unable to explain the high concentrations.

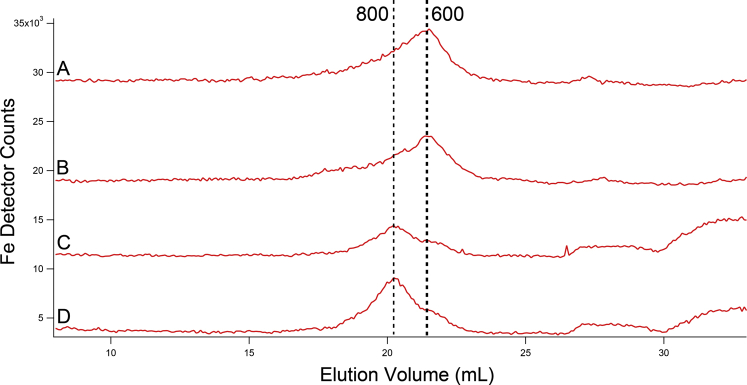

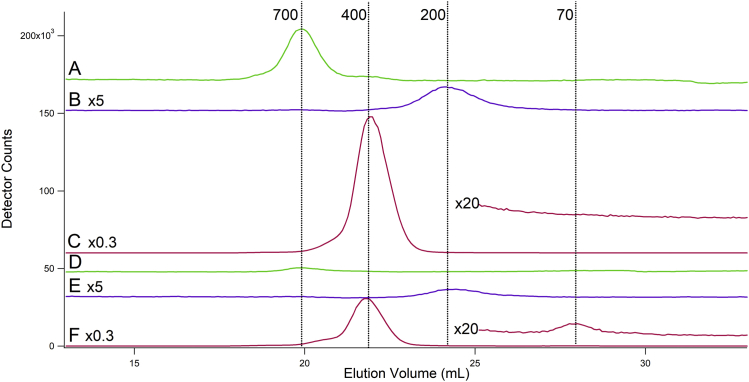

FTSs were subjected to LC-ICP-MS chromatography. The resulting traces (Fig. 4) revealed unresolved LMM iron-detected peaks for each strain. The dominant LMM iron species in WT cytosol FTS migrated with an apparent mass of ∼600 Da (all masses quoted in the text are apparent), whereas the dominant LMM iron species in vma2ΔW cytosol FTS migrated with a mass of ∼800 Da. Both species were present in the FTS of both strains, and their collective intensities were similar. We conclude that the LMM iron in the cytosolic FTS of vma2ΔW and WT cells are similar though not identical in terms of species and concentration. We caution readers that about half of the LMM iron in the cytosolic fraction adsorbed onto the column.

Figure 4.

Iron-detected chromatogram of isolated cytosol FTS.A–B, two independent WT batches; C–D, two independent vma2ΔW batches. WT chromatograms for Fe and elements in subsequent figures were from (38). FTS, flow-through solution.

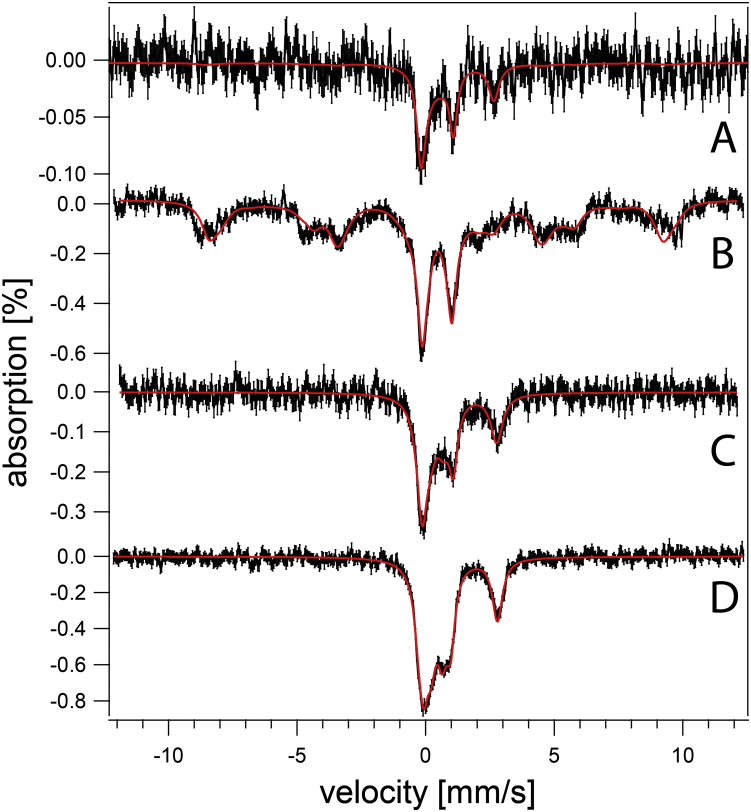

We considered that much of the NHHS FeII in vma2ΔW cells was located in the mitochondria, and so this organelle was isolated from both WT and vma2ΔW strains (grown on fermenting MM at pH 5). MB spectra of isolated mitochondria from each strain (Fig. 5) were dominated by the CD (ca. 80% intensity). A minor NHHS FeII doublet (15%–20%) was also evident. Aconitase activities in these mitochondrial lysates were similar (WT = 2.6 ± 1.2 units/mg protein, vma2ΔW = 2.3 ± 1.2 units/mg protein; n = 2). Little if any FeIII oxyhydroxide nanoparticles were present in vma2ΔW mitochondria, unlike mitochondria from strains in which ISC assembly is defective. In summary, the iron contents of mitochondria isolated from WT and vma2ΔW cells, as evaluated by MB spectroscopy and by the activity of an ISC-containing enzyme, were similar. The low-intensity NHHS FeII doublet observed in WT and vma2ΔW mitochondria indicate that mitochondrial FeII alone cannot account for the dominating FeII intensities observed in vma2ΔW whole-cell MB spectra.

Figure 5.

Mössbauer spectra of mitochondria isolated from two independent batches of fermenting cells (MM supplemented with 40 μM ferric citrate and 10 μM copper sulfate).A–B, from WT cells; C–D, from vma2ΔW cells. MM, minimal medium.

We wondered whether the metabolic state of vma2ΔW cells (fermenting versus respiring) affected the iron content of the cells. To address this, WT and vma2ΔW cells were grown on a respiring carbon source (glycerol/ethanol) in MM buffered at pH 5 and supplemented with 40 μM 57FeIII citrate. In this case, vma2ΔW cells required prior growth in glucose-based media before switching to respiring MM. About 65% of the intensity of the resulting MB spectrum of WT cells (Fig. 6B) arose from vacuolar high-spin FeIII (10, 11); another ca. 25% arose from the CD. The higher intensity observed for the CD confirms that respiration-related ISC proteins are upregulated during respiration (36). In contrast, the MB spectrum of respiring vma2ΔW cells (Fig. 6D) lacked the magnetic feature arising from vacuolar FeIII but exhibited an FeII doublet representing ∼40% of spectral intensity. Over half of the spectral intensity arose from the CD combined with unresolved iron in the middle of the spectrum which fit to a doublet with the parameters of nanoparticles. The cellular concentrations of [Fe4S4]- and LS FeII heme-containing species in respiring WT and vma2ΔW cells were again similar, as observed for fermenting cells. In summary, the iron content of respiring vma2ΔW cells was similar to that of WT cells, though with a dominance of FeII instead of vacuolar high-spin FeIII. The simplest interpretation is that vacuolar FeIII in WT cells are converted to NHHS mononuclear FeII and FeIII nanoparticles in fermenting and respiring vma2ΔW cells.

Figure 6.

Mössbauer spectra of respiring WT (A–B) and vma2ΔW(C–D) cells grown on media supplemented with 1 (A and C) and 40 (B and D) μM57FeIIIcitrate and 10 μM copper sulfate and at pH 5.

We considered that some of the dominant NHHS FeII species in iron-replete vma2ΔW cells were present in vacuoles, and so two batches of vacuoles from vma2ΔW cells were isolated and FTSs were prepared. LC traces of these solutions exhibited LMM iron peaks that were either of similar intensity as peaks from WT vacuoles – or less intense (data not shown). However, these studies used a column that was not treated such that adsorption of iron was considerable. We considered that vma2ΔW vacuoles contained additional iron that adsorbed onto the column, but the iron concentration of those vacuoles was not unusually high.

Cells grown in media containing low concentrations of iron do not store much of the metal in their vacuoles. Thus, the contribution of vacuolar iron to MB spectra can be largely eliminated by growing cells under these conditions. The MB spectrum of respiring WT cells grown in MM supplemented with 1 μM 57Fe citrate (Fig. 6A) was noisy because the cells contained only 180 μM Fe. However, the S/N was sufficient to conclude that the vacuolar FeIII feature was essentially absent (<15% of spectral intensity). The corresponding spectrum of vma2ΔW cells, containing 220 μM Fe (Fig. 6C), also lacked the vacuolar FeIII feature and also exhibited an intense CD (even stronger than for WT cells). This indicates that vma2ΔW mitochondria were fully able to generate [Fe4S4] clusters (and LS FeII hemes). We conclude that vma2ΔW mitochondria were able to import cytosolic iron and were able to use it for ISC assembly even though vacuoles were largely devoid of iron. This behavior was unexpected, given previous results which indicated a strong need for functional acidic vacuoles to deliver iron to mitochondria during mitochondriogenesis associated with respiration, as well as with the reported rescue of growth of vma-mutant cells with high (mM) concentrations of nutrient iron (22, 24, 26). In summary, these experiments performed with only 1 μM added iron gave essentially the same result in vma2Δ cells, showing a normal ISC pool in cells where vacuoles did not store significant iron.

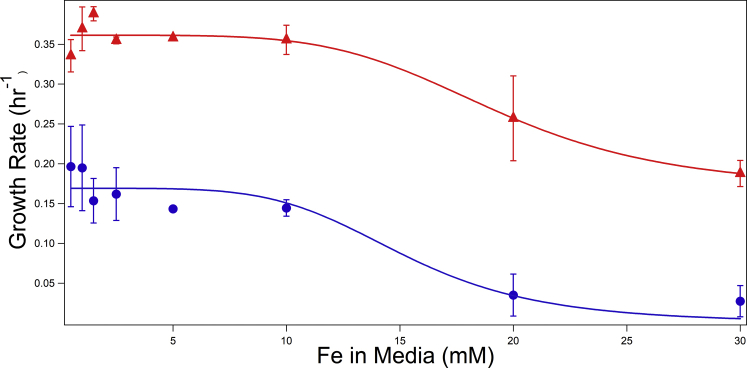

To further gauge the vacuolar iron content of WT and vma2ΔW cells, we cultured such cells in high (mM) concentrations of nutrient iron and monitored growth rates. As yeast lack a means of exporting iron, vacuolar iron storage typically provides resistance to excessive iron levels. WT cells grew rapidly until 20 to 30 mM FeIII citrate had been added to the growth medium, beyond which the growth rate declined (Fig. 7, triangles). vma2ΔW cells grew slower than WT in medium containing up to 10 mM iron and grew poorly in media containing higher iron concentrations (Fig. 7, circles). We suspect that under these high-iron conditions, vma2ΔW cells were unable to sequester toxic iron in their vacuoles in a nontoxic form.

Figure 7.

Plot of the exponential growth rate α of fermenting WT (red triangles) and vma2ΔW(blue circles) versus the concentation of FeIIIcitrate added to the growth medium. Points are the averages of 2-3 independent batches; bars represent standard error. The solid red line is a simulation using Equation 1 and αcyt = 0.185 h−1, αvac = 0.176 h−1, and Kα = 15 mM. The solid blue line is the same except αvac = 0.

The shapes of the plots of Figure 6 suggested that we could simulate growth rates using Equation 1:

| (1) |

which assumes two contributions to the growth rate, one that is sensitive to excessive iron in the media (αcyt) and another that is not (αvac). The observed experimental growth rate α was the slope of the ln(OD600) versus time in the exponential growth region. This empirical equation may only apply to the range of media iron concentrations investigated. It implies that excess cytosolic iron is toxic, whereas iron sequestered in the vacuole is not, as least in WT cells. The red line in Figure 7 simulates the growth rate of WT cells in which vacuoles sequester iron from the cytosol. The blue line simulates the growth of vma2ΔW cells in which vacuoles are presumed unable to sequester iron in a benign form such as FeIII polyphosphate.

vma2ΔW cells grew more slowly than WT cells, even in media that was not supplemented with iron at high concentrations. Our MB studies indicate that these cells accumulated FeII ions. We considered that the FeII species in vma2ΔW cells might be susceptible to Fenton chemistry and that this caused slow growth. We investigated this by treating two of the 57Fe-enriched samples used to generate spectra in Figure 2 with H2O2. In both experiments, the resulting MB spectra did not change noticeably – the NHHS FeII doublet continued to dominate (data not shown).

We also probed the effect of varying phosphate supplementation on the WT and vma2ΔW strains, the latter of which contains little vacuolar polyphosphate (16). We grew both WT and vma2ΔW cells in media containing low (0.5 mM) and high (21 mM) supplemented phosphate. This treatment did not have an effect on the oxidation state of iron in vma2ΔW cells (Fig. S1). Both high- and low-phosphorus vma2ΔW spectra were dominated by the FeII doublet. Curiously, the spectrum of high-phosphate cells exhibited a quadrupole doublet with parameters typical of FeIII oxyhydroxide phosphate–associated nanoparticles. The same doublet was present in the low-phosphate spectrum, albeit at lower intensity. This result suggests that in vma2ΔW cells, the formation of nanoparticles may have been limited by phosphate rather than iron. In contrast, the presence of high or low phosphate in the growth media had no noticeable effect on iron in WT cells.

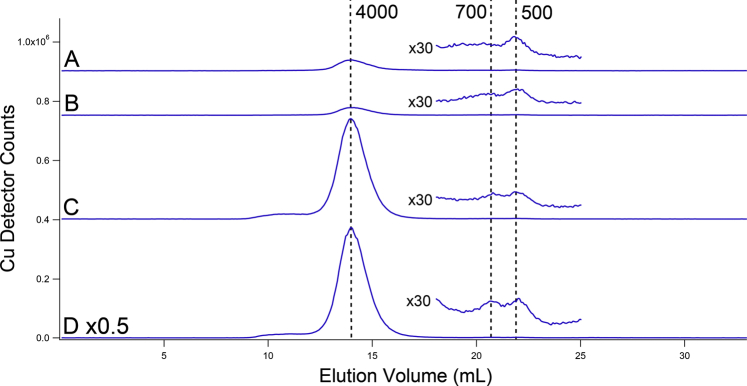

Although iron was our major focus, ICP-MS provides information on other elements, and so we also monitored Cu, Mn, Zn, S, and P. Copper was especially interesting because vacuoles also function in copper homeostasis. FTS from vma2ΔW cytosol exhibited an intense copper-detected peak with an apparent mass of 4000 Da (Fig. 8). This peak was tentatively assigned to metallothionein Cup1 (38). The greater intensity of this peak in vma2ΔW cytosol FTS relative to WT suggested greater expression of Cup1 and/or more extensive copper binding to this protein in vma2ΔW cells. This makes sense because vma2ΔW cells contained 2.5× more copper than WT cells (Table 1) and Cup1 sequesters copper. The same trend was reflected in the copper concentration of isolated cytosol (Table 1). The lack of a CuII-based EPR signal in vma2ΔW cells is consistent with diamagnetic CuI binding to metallothioneins. Also present were ca. 2 low-intensity Cu peaks in the range of 500 to 700 Da; their intensities were similar for both vma2ΔW and WT FTSs (Fig. 8, insets).

Figure 8.

Copper-detected chromatograms of cytosol FTS from two batches of WT (A–B) and vma2ΔW(C–D) cells. FTS, flow-through solution.

LMM sulfur–based LC peaks were also detected in cytosolic FTSs from both WT and vma2ΔW cells (Fig. 9). The dominant sulfur peak in the FTS from both cells (Ve = 20 ml) originated from the sulfur-containing MES buffer used early on in isolating the cytosol. The right shoulder of this peak coeluted with numerous sulfur standards including but not limited to cysteine (Fig. 9F). In vma2ΔW cytosol FTS, the intensity of the shoulder was greater relative to that of WT FTS. The sulfur peak at an apparent mass of 100 Da. originated from the PMSF added to the buffer during isolation; the sulfur peak at an apparent mass of 50 Da originated from the DTT used earlier during isolation.

Figure 9.

Sulfur-detected chromatograms of cytosol FTSs and standards. A–B, two batches of WT cytosol FTS. C–D, two batches of vma2Δ cytosol FTS. E–J, standards with areas normalized to indicate peak position. E, Na2S, F, cysteine, G, methionine, H, reduced glutathione, I, MgSO4, J, oxidized glutathione. The intense peak at ca. 20 ml in A–D is due to MES buffer (10 mM). FTS, flow-through solution.

Hughes et al. (26) recently suggested that increased concentrations of cytosolic cysteine in vma2-mutant cells inhibited the vacuole-to-mitochondria iron trafficking pathway. To examine this, we grew vma2ΔW cells on fermenting MM (pH 5) supplemented with 1 mM cysteine. The MB spectra of such cells were unaffected by cysteine supplementation (Fig. 3B) except for a modest decline in the CD (22% in the spectrum of unsupplemented vma2ΔW cells down to 14% for the same cells supplemented with cysteine). Hughes et al. (26) suggested that cysteine supplementation caused “bioavailable” iron to decline and nonvacuolar cysteine to accumulate. The MB spectrum of the cysteine-supplemented vma2ΔW sample did not show an increase in FeIII nanoparticles, a form of iron considered to be bio unavailable.

Mn and Zn chromatograms of vma2ΔW and WT cytosol (Fig. 10, A–B) were like those described previously (38), including a single Zn peak at 700 Da and a single Mn peak at 200 Da. Phosphorus chromatograms (Fig. 10, C–F) exhibited a major peak at 400 Da and a shoulder at 600 Da. The intensities of Mn, Zn, and P peaks were significantly lower in vma2ΔW traces, consistent with the lower concentration of these elements in mutant cells and isolated cytosol (Table 1). Notably, only the P peaks at 400 Da declined in intensity for vma2ΔW cytosol; the peak at 600 Da remained the same. The peak at 70 Da comigrated with an AMP standard.

Figure 10.

Zn-, Mn-, and P-detected chromatograms of cytosol FTS from WT (A–C) and vma2ΔW(D–F) cells. Each displayed Zn (A and D), Mn (B and E), and P (C and F) trace is the average of two traces from independent batches. FTS, flow-through solution.

We were puzzled that many of the results obtained using vma2ΔW cells differed from published results on what was ostensibly the same mutant. However, the strain used to generate the mutant in those reports was BY4741, whereas ours was W303. We obtained the mutant in the BY4741 strain (to be called vma2ΔB) and collected MB spectra of those cells grown at different pHs in fermenting MM supplemented with 40 uM 57Fe citrate. vma2ΔB cells grown at low pH exhibited spectra that were virtually indistinguishable from WT cells, including an intense magnetic feature due to vacuolar FeIII (Fig. 11E versus Fig. 11B). At higher pH, vma2ΔB cells exhibited spectra dominated by a broad quadrupole doublet due to FeIII nanoparticles (Fig. 11C–D). Also, the percent absorbance was higher than in WT spectra, similar to that observed for ISC-mutant cells with an activated iron regulon (19, 20, 21). The spectra of vma2ΔB cells grown at intermediate pH contained a stronger-than-WT NHHS FeII doublet (Fig. 11D), with parameters similar to those used to simulate the FeII doublet in vma2ΔW cells.

Figure 11.

Mössbauer spectra of fermenting BY4741 (A–B) and vma2ΔB(C–E) cells grown in media buffered at the following pH values.A, 6; B, 3; C, 5; D, 4; E, 3.

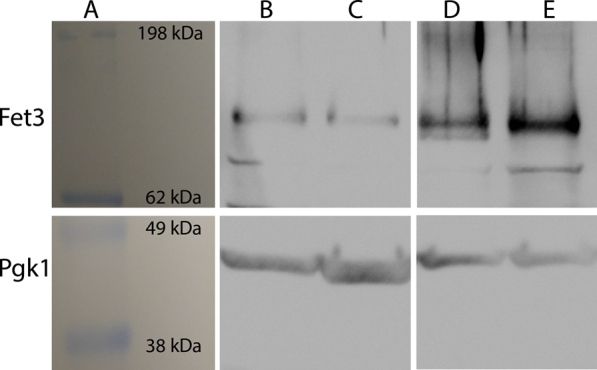

We attributed the differences between our results and those in the literature to differences between the W303 and BY4741 background strains. Notably, our experiments had not indicated an iron trafficking defect in the vma2ΔW cells. Prompted by a reviewer’s comment, we sought to determine by Western blot of whole-cell extracts whether the iron regulon in vma2ΔW cells was activated by monitoring the relative abundance of the high-affinity iron importer Fet3. Cytoplasmic Pgk1 was a positive control. We did not observe a significant difference in Fet3 abundance between WTW W303 and vma2ΔW cells (Fig. 12, top row, B and C respectively), indicating that the iron regulon is not activated. In contrast, Fet3 was more abundant in vma2ΔB versus WT BY4741 cells (Fig. 12, top row, E versus D respectively), supporting previous studies indicating that the iron regulon is activated in vma2ΔB cells grown in yeast extract peptone adenine dextrose medium (YPAD) media (22, 23).

Figure 12.

Western blot of fermenting WT and vma2Δ whole-cell extract from both W303 and BY4741 background strains.Top row, anti-FET3. Bottom row, anti-PGK1. A, image of prestained protein ladder with masses indicated. B–C, w303 WT and vma2Δw, respectively, cultured in MM supplemented with 40 μM iron. D–E, BY4741 WT and vma2ΔB, respectively, cultured in YPAD. All bands in each row were run on the same gel. MM, minimal medium, YPAD, yeast extract peptone adenine dextrose medium.

Discussion

As described in the Introduction, there is significant evidence for an iron trafficking pathway from vacuoles to mitochondria in yeast. Vacuoles store iron that is needed for mitochondriogenesis especially when cells shift from fermentation to respiration. Nonacidic vacuoles with defects in V-ATPase have been reported to generate mitochondrial defects in ISC synthesis and iron homeostasis. Our initial objective was to probe this relationship and defects in vma2ΔW cells by MB and EPR spectroscopies and LC-ICP-MS chromatography. However, analyzing our results was more challenging than anticipated.

One result was clear: most of the iron in fermenting vma2ΔW cells was nonheme high-spin FeII. In W303 cells, approximately the same percentage of iron was HS FeIII, previously assigned to vacuolar iron. The overall iron concentrations in WT and vma2ΔW cells and the spectral contributions of the CD (due to [Fe4S4]2+ clusters and LS FeII hemes) were also similar. We conclude that vacuolar FeIII ions in WT cells are reduced to the FeII state in vma2ΔW cells. We suspect but are not certain that the FeII remains in the organelle. We have observed a similar FeIII → FeII reduction of vacuolar iron in yeast cells grown on adenine-deficient media in which metabolism has been altered (39). Some vacuolar iron in iron-replete respiring vma2ΔW cells was reduced to FeII (and some may have formed FeIII nanoparticles).

The reduction of FeIII to FeII as the acidity of vacuoles declines can be partially or wholly explained by the conclusions of Raguzzi et al. (40) and Singh et al. (41) using insights from Schafer and Buettner (42). These researchers hypothesized that the glutathione redox couple controls the redox status of vacuoles in accordance with the Nernst equation:

The standard half-cell reduction potential at pH 7 is E0(pH7)GSH = −240 mV, whereas at pH 6, it is E0(pH6)GSH = −180 mV (i.e., more oxidizing under acidic conditions). On this basis, they correctly predicted that the iron in WT vacuoles should be FeIII. For each pH increase of 1 (a 10-fold drop in acidity), the effective reducing power of glutathione increases by 59 mV. Assuming pH 6 to 7 in vma2Δ vacuoles, the thermodynamic reduction potential for the FeIII/FeII couple in vacuoles should be in the range of the values listed above.

Interestingly, the same analysis predicts that the FeII should reoxidize to FeIII in vma2ΔW cells grown at lower pH, which was not observed; the dominant iron in these cells remained FeII for pH values as low as 3. Perhaps the pH of vma2Δ vacuoles is less sensitive to media pH than we have assumed. Other factors may also be involved (43). The redox state of vacuolar iron is likely influenced by the potential ligands in the organelle. For instance, vacuolar iron is coordinated by polyphosphate anions, and the concentration of these chains is diminished in vma2Δ vacuoles (16).

Diab and Kane predicted that vma2Δ cells should contain high levels of FeII ions (23). These researchers suggested that this form of iron is toxic to the cell because it participates in Fenton chemistry {FeII + H2O2 → FeIII + OH− + OH·}. However, we treated vma2ΔW cells with H2O2 but found no evidence using MB spectroscopy that the FeII was altered in peroxide-treated cells. Reducing equivalents in the cell may have quickly reduced FeIII back to FeII such that FeII remained dominant in the treated cells despite being used in Fenton chemistry. Upregulation of the cytosolic peroxidase Tsa2 in vma2Δ cells may have also diminished the effects of H2O2 (22).

Many of our results differed from expectations based on previous studies of vma2ΔB cells. To examine whether there might be a strain dependence, we collected MB spectra of vma2ΔB cells grown at different media pH values. Resulting spectra were closer to our expectations, with WT-looking vacuolar FeIII in vma2ΔB cells grown at low pH and NHHS FeII and nanoparticles for cells grown at high pH. BY4741 and W303 cells have different plasma membrane potentials and different sensitivity to alkali-metal salts (44). W303 cells are larger than BY4741 cells, their overall protein concentration is lower, and their vacuoles occupy a greater fractional cell volume (45). We found that vma2ΔW cells were less sensitive to media pH and exhibited milder phenotypes associated with nonacidic vacuoles such that mitochondria were largely unaffected under the conditions used. We speculate that this reduced sensitivity might reflect larger vacuoles (a lower surface-to-volume ratio and therefore a smaller interface with the cytosol) in W303 cells, but further studies are required to verify this.

We have compared our results mainly to those of Kane and Hughes, but other studies report results regarding vma mutants that are more similar to ours. Ohya et al. (46) found that O2 consumption rates in vma-mutant cells (from parent strains other than W303 or BY4741) grown on glucose were “identical” to those of WT cells. They also reported no significant change in F-ATPase and succinate dehydrogenase activities, consistent with our results and with our suggestion of strain-dependent differences in vma-mutant phenotypes.

Hughes et al. (26) suggested that cytosolic accumulation of cysteine drives the low iron and oxidative stress response in V-ATPase–deficient cells. We observed a LMM sulfur species in isolated cytosol from WT and vma2ΔW cells and found that its intensity increased in Vma2Δw FTS relative to that of traces of WT FTSs. This shoulder to the MES buffer peak approximately comigrated with cysteine and other LMM sulfur species, including GSH and methionine. The increased shoulder intensity in vma2ΔW isolated cytosol is consistent with the findings of Hughes et al., though further confirmation of elevated cytosolic cysteine levels is required.

vma2ΔW cells grew slower than WT cells and were more easily intoxicated by high concentrations of iron in the medium. We simulated these differences by assuming that vma2ΔW cells are unable to sequester iron (or unable to sequester it in a benign form). However, the situation is undoubtedly more complicated. The toxicity of imported iron may also be associated with the oxidation state of that iron, with FeII being more toxic than FeIII.

vma2ΔW cells and cytosol contained less Mn than in WT cells and cytosol; a similar decline has been observed in PPN1-UP cells (47) which have elevated levels of the polyphosphatase Ppn1. In both strains, cells contain low levels of polyphosphate relative to WT. Mn binds vacuolar polyphosphate (12), suggesting that these mutant cells may have responded to a decreased capability to store Mn in vacuoles by slowing Mn import.

The decline of phosphorus in vma2ΔW cells and cytosol may be related to changes in the activity/expression levels of Pho84 and Pma1, both of which are located on the plasma membrane (14). Pho84 is a symporter that imports protons and phosphate ions into the cytosol; Pma1 exports protons from the cytosol. The activity of Pma1 decreases in vma mutants (7), which along with the loss of V-ATPase activity increases the acidity of the cytosol. We speculate that this might decrease the activity of Pho84 and thus reduce the import of phosphate into vma cells. Pho84 may also be involved in manganese and zinc import (48), and a decline in activity could have contributed to the observed decline of Mn and Zn concentrations in vma2ΔW cells.

The increased concentration of Cu in our vma2ΔW cells and cytosol confirms earlier reports that vma-mutant cells contain high levels of copper and that copper is dysregulated in these cells (17, 24). A similar accumulation may be driving the reported decline in Ctr1 expression in vma2ΔB cells (22). Most LMM Cu in both WT and vma2ΔW cytosol is probably bound to metallothionein Cup1. Higher copper concentrations in vma2ΔW cells likely afforded increased levels of Cu-bound Cup1. The inability of nonacidic vacuoles to sequester copper may have increased the concentration of cytosolic Cu, which in turn induced expression of CUP1. Another possibility is that Cu-bound Cup1 is mobilized to vacuoles for degradation and that this process is inhibited in nonacidic vacuoles, thereby causing a buildup of Cu-bound Cup1 in the cytosol. A similar peak was tentatively assigned to Cup1 in chromatograms of vacuolar lysates (12).

Does iron trafficking in Saccharomyces cerevisiae include a direct or dedicated vacuole-to-mitochondria pathway? A direct pathway would involve contact of the two organelles (kiss-and-run) and would be independent of cytosol. A dedicated pathway would involve the synchronized export of a particular iron species from the vacuole into the cytosol, and as a second step, the import of that species exclusively into mitochondria. If the iron exported from vacuoles entered a cytosolic pool of iron that had various trafficking destinations, including but not limited to mitochondria, we would not regard that pathway as being direct or dedicated.

We have not systematically distinguished these possibilities, but our results disfavor direct or dedicated pathways. The vacuoles are nearly empty in cells grown in iron-deficient or iron-limited media (e.g., 1 μM 57Fe citrate), yet MB spectra of such vma2ΔW cells afforded a CD as intense as for equivalent WT cells. This suggests that vacuoles are unnecessary for iron to enter mitochondria and be used to generate ISCs. We tentatively conclude, pending further investigations, that cytosolic iron can enter mitochondria directly without first entering and exiting vacuoles and that there is no direct/dedicated vacuole-to-mitochondria trafficking pathway as defined above.

So how does the nonacidity of vacuoles negatively impact ISC metabolism in mitochondria? We suggest, following Hughes (26), that the effect indirectly involves vacuoles and directly involves the cytosol. Cysteine or a derivative thereof may be blocked from entering nonacidic vacuoles, and its buildup in the cytosol may inhibit iron traffic into mitochondria. Likewise, a hyperacidic cytosol, caused by the absence of V-ATPase to pump cytosolic protons into vacuoles and/or a decline in Pma1 activity, may also hinder iron trafficking. In support of this, we observed a shift in the LMM iron species in vma2ΔW cytosol, from dominance of a species with an apparent mass of 600 Da to one with an apparent mass of 800 Da.

Finally, we have had difficulty throughout this study reconciling the milder phenotype of the vma2ΔW strain with the more dramatic phenotype of vma2ΔB. Both mutant cells grow slowly and with difficulty under respiring conditions, but vma2ΔW mitochondria are indistinguishable (by our methods) from WT mitochondria. In contrast, vma2ΔB mitochondria show difficulty generating ISCs, the iron regulon is clearly activated, and nanoparticles and ROS are likely generated. Those cells recover only under conditions in which the media is supplemented with excessive iron.

We suggest that vma2ΔW mitochondria suffer from the same originating problem as vma2ΔB but to a milder degree. We hypothesize that the fundamental problem is a slow rate of iron import from the cytosol to mitochondria, due to the hyperacidity of this cellular region and/or to the inhibitory effect of high cysteine concentrations. The effect of slow iron import into mitochondria on the growth of vma2ΔW cells would not be evident from our studies because we patiently waited for them to grow to sufficient absorbance at 600 nm prior to harvesting them for MB spectroscopy. By doing this, the ultimate iron content is expected to be like that of WT cells (apart from the reduction of vacuolar FeIII → FeII). For vma2ΔB cells, the rate of iron traffic from the cytosol to the mitochondria might be so slow that the respiratory shield weakens and a vicious cycle ensues, leading to nanoparticles, ROS, and an activated iron regulon, similar to that observed in Mrs3/4ΔΔ cells, which can only import iron slowly into mitochondria under iron-limited growth conditions (49, 50). In vma2ΔW cells, this effect might be muted.

Experimental procedures

Generation of the vma2Δ strain

Studies were conducted with the haploid strain of S. cerevisiae, W303 (MAT α ade2-1, his3-3-11, 15 leu2-3,112, trp1-1, ura3-1). The VMA2 open reading frame was deleted in W303 by the Longtine method (51). Primers were synthesized including VMA2 gene specific sequences (lower case) and plasmid specific sequences (upper case): F1 (agagtagacagtacatcaagcgaaaataaatattgcagga/CGGATCCCCGGGTTAATTAA); R1 (gacaaaataaaaaaagcctttttcttcagcaaccgtcctc/GAATTCGAGCTCGTTTAAAC).

A PCR was performed on template plasmid pF6A-His3MX6 (51) carrying the S. pombe his5+ gene, and a 1403-bp DNA fragment was amplified as expected. The DNA product (about 5 μg) was used to transform W303 yeast using the lithium acetate procedure (52), and several colonies were selected for histidine prototrophy and carried forward. The correctness of the VMA2 deletion was verified as follows. Genomic DNA was extracted from the transformants, and a PCR, using forward primer I (ctcatgaccgatggtacg) and reverse primer N (ATGTGATGTGAGAACTGTATC), was performed. The I primer resides in the 5’ region of VMA2 gene outside the region of recombination. The N primer resides in the TEF terminator region of the pF6A-His3MX6 plasmid. The derived PCR product was approximately 688 bp in size and was present in the knockouts but not in the controls (Fig. S2), confirming that the VMA2 flanking region and His3MX6 module including the S. pombe his5+ gene were correctly juxtaposed in the genome of the putative knockouts. The knockout strains had the expected auxotrophies and prototrophies and grew more slowly than the parent on rich or defined media.

Cell growth

W303 WT (MAT α ade2-1 his3-11,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1) and W303 vma2Δ (MAT α ade2-1 his3-11,14 leu2-3,112 trp 1-1 ura3-1 Δvma2::His3MX6) cells were obtained from frozen 15% glycerol stocks on YPAD (2% (w/v) glucose, 1% (w/v) yeast extract, 2% (w/v) peptone, 0.01% (w/v) adenine, 2% (w/v) bactoagar) plates. BY4741 WT (MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0) and congenic BY4741 (∆vma2::KanMX6) cells were maintained similarly.

Individual colonies were inoculated in precultures of MM (20 g/l glucose, 5 g/l ammonium sulfate, 1.7 g/l yeast nitrogen base without ammonium sulfate and ferric chloride (MP Bio), 100 mg/l leucine, 50 mg/l adenine, 20 mg/l histidine, 20 mg/l uracil, 48 mg/l tryptophan, 10 μM copper sulfate) and either 1 or 40 μM ferric citrate. For two batches, the medium was supplemented with 1 mM cysteine. Media were buffered with a 0.05 M citric acid/sodium citrate buffer in varying ratios. For pH 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7, the citric acid-to-sodium citrate ratio was 13.3:1, 1.9:1, 1:1.4, 1:4.4, and 0:1, respectively. Minor adjustments were made with NaOH to achieve the desired media pH, as monitored using an Accumet AB15 pH meter.

BY4741 cells for Western Blot were cultured in YPAD media (20 g/l glucose, 10 g/l yeast extract, 20 g/l peptone, 100 mg/l adenine). Cell cultures were incubated at 30 °C and 180 rpm shaker speed. Absorbance was monitored at 600 nm using a Genesys6 spectrophotometer (Thermofisher). Fifty to 100 ml of precultures was transferred to 1- to 2-l media when absorbance at 600 nm was 0.7 ± 0.1. Cells were harvested from 1 to 2 l when culture was at exponential phase (absorbance at 600 nm = 0.8 ± 0.2). Cells were pelleted via centrifugation at 5000g for 5 min using a Sorvall LYNX6000 superspeed centrifuge (Thermofisher). Cells were washed twice with 1 mM EDTA and then twice with deionized water (5 ml of wash per gram wet cell pellet). After each wash, cells were pelleted as above and the supernatant was discarded. Finally, pellets were suspended in a minimal volume of double-distilled water and pelleted into MB cups by centrifugation at 6400 RPM for 10 min using a Beckman Coulter Optima L-90K ultracentrifuge (SW32Ti rotor); samples were frozen in liquid N2 for later analysis. EPR samples were pelleted after washing by centrifugation at 5000g for 5 min into EPR tubes.

For H2O2 studies, whole-cell MB samples were thawed and incubated in 1 ml 5% H2O2 for 15 min or in 200 μl of 0.0034% H2O2 (initial concentrations) overnight. Cell pellets were reacquired for MB spectroscopy via centrifugation at 5000g for 5 min.

Respiring cell growth

Cell cultures were initially grown in 50 mL of fermenting MM as above. Once absorbance at 600 nm reached 0.6, the cells were pelleted and resuspended in 1.00 L of respiring MM (same as fermenting MM pH 5 except that 3% (v/v) glycerol and 1.5% (v/v) ethanol replaced glucose). Cells were harvested as described above.

Varying phosphate cell growth

Cell cultures were grown in fermenting CSM media at 30 °C and 180 RPM. CSM media consisted of 20 g/l glucose, 1.6 g/l CSM, 5.6 g/l yeast nitrogen base minus phosphates (MP Bio), 100 mg/l NaCl, 60 mg/l adenine, 100 mg/l leucine, 48 mg/l tryptophan, 10 μM copper sulfate, and 40 μM ferric citrate. The medium was supplemented with 0.5 and 21 mM monopotassium phosphate. All such studies were conducted at pH 5 using a 0.05 M citric acid/sodium citrate buffer. Cells were harvested as above.

Mössbauer and EPR spectroscopies

Mössbauer spectra were collected at 5 K and 0.05 T on a MS4 WRC spectrometer (SEE Co, Minneapolis, MN) calibrated at RT using an α-iron foil. The applied field was parallel to the gamma radiation. EPR spectra were collected in an X-band Elexsys EPR spectrometer (Bruker) using the following conditions: 9.3789 GHz microwave frequency, 25 dB attenuation, 0.6325 mW power, 100 kHz modulation, 10G modulation amplitude, 5000G sweep width, 120 s sweep time, 5 to 10 scans.

Mitochondria studies

Mitochondria were isolated anaerobically from cells harvested from 24 L of fermenting cell cultures (pH 5), as described (35). Mitochondrial protein concentration was determined using the BCA assay. Mitochondria were pelleted via centrifugation at 12,000g for 10 min.

Aconitase was assayed as described (53, 54) but with minor changes. Mitochondria were handled within an anaerobic glove box (MBraun Labmaster 130) containing c.a. 5 ppm O2. A pellet of mitochondria containing 80 mg of protein was diluted to 250 μl with lysis buffer (degassed 4.7 mM Triton X-100, 50 mM NaCl, and 50 mM Tris-HCl). Two hundred microliters of the resulting solution was mixed with 200 μl of 50 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl, and 50 μl of double-distilled water in a 1-mm pathlength quartz cuvette. The sample was sealed with a rubber septum and removed from the box. Fifty microliters of 10 mM cis-aconitic acid (Sigma-Aldrich) was added through the septum, and the sample was mixed and immediately monitored at 240 nm for 360 s using a Hitachi U-3310 spectrophotometer. The molar absorptivity of cis-aconitic acid at 240 nm (ε240) was 4.88 mM−1 cm−1 (54).

Cytosol and vacuole isolation

The cytosol was isolated from fermenting cells (pH 5) and filtered through a 10-kDa cutoff membrane as described (55). Filtered FTS was injected into a treated size-exclusion (SEC) Superdex Peptide 10/300 Gl column (GE Life Sciences) connected to an Agilent 1260 Bioinert quaternary pump (G5611A) and Agilent 7700x ICP-MS. The mobile phase was 20 mM ammonium acetate pH 6.5 flowing at 0.6 ml/min. Vacuoles were isolated as described (12).

Western blot

Western blot was completed using the whole-cell extract as described (12, 55). An anti-Fet3 antibody from rabbit was used in a 1:1000 dilution. The antibody was generated as described (28).

Elemental analysis

Isolated cytosol samples (100 μl) or double-distilled water–washed whole cells (ca. 100 mg) suspended in fresh double-distilled water were digested with 500 μl of undiluted (70%) trace metal–grade HNO3 (Fisher) at 70 °C for ca. 16 h in plastic falcon tubes sealed using electrical tape. Samples were cooled to RT, and 250 μl of 35% hydrogen peroxide was added. Samples were resealed and incubated at 65 °C for 90 min. Samples were diluted to 10 ml with double-distilled water, affording c.a 3.5% and 0.86% (w/w) final concentrations of trace metal–grade nitric acid and hydrogen peroxide, respectively. A cell pellet packing efficiency of 0.7 and whole-cell pellet density of 1.1029 g/ml (56) were used in calculations.

Data availability

All data except those described as “Data not shown” in the text are contained within the manuscript and SI.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank Patricia Kane for providing the vma2Δ strain in BY4741 background and Joel P. Ferrer and Raynelle L. Nash for preparing samples early in this study.

Author contributions

J. E. K. performed most of the experiments and analyzed all results; S. W. V. collected the Mössbauer and electron paramagnetic resonance spectra and maintained those instruments; T. Q. N. performed some experiments and training; A. D. performed all genetic manipulations; P. A. L. conceived of the project, offered advice, analyzed results, and wrote most of the article. All authors edited the article and approved of its publication.

Funding and additional information

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (GM127021 to P. A. L. and GM107542 to A. D.), the National Science Foundation (MCB-1817389), a T3 grant from Texas A&M University, and the Robert A. Welch Foundation (A1170). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation, or the Welch Foundation.

Edited by Ruma Banerjee

Footnotes

This article contains supporting information.

Supporting information

References

- 1.Szczypka M.S., Zhu Z.W., Silar P., Thiele D.J. Saccharomyces cerevisiae mutants altered in vacuole function are defective in copper detoxification and iron-responsive gene transcription. Yeast. 1997;13:1423–1435. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199712)13:15<1423::AID-YEA190>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Urbanowski J.L., Piper R.C. The iron transporter fth1p forms a complex with the Fet5 iron oxidase and resides on the vacuolar membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:38061–38070. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.53.38061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kane P.A. The where, when, and how of organelle acidification by the yeast vacuolar H+-ATPase. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2006;70:177–191. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.70.1.177-191.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Plant P.J., Manolson M.F., Grinstein S., Demaurex N. Alternative mechanisms of vacuolar acidification in H+-ATPase-deficient yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:37270–37279. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.52.37270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kane P.M. The long physiological reach of the yeast vacuolar H+-ATPase. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2007;39:415–421. doi: 10.1007/s10863-007-9112-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kane P.M. Proton transport and pH control in fungi. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2016;892:33–68. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-25304-6_3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martinez-Munoz G.A., Kane P.M. Vacuolar and plasma membrane proton pumps collaborate to achieve cytosolic pH homeostasis in yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:20309–20319. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710470200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nelson H., Nelson N. Disruption of genes encoding subunits of yeast vacuolar H+-ATPase causes conditional lethality. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1990;87:3503–3507. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.9.3503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sambade M., Alba M., Smardon A.M., West R.W., Kane P.M. Genomic screen for yeast vacuolar membrane ATPase mutants. Genetics. 2005;170:1539–1551. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.042812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cockrell A.L., Holmes-Hampton G.P., McCormick S.P., Chakrabarti M., Lindahl P.A. Mössbauer and EPR study of iron in vacuoles from fermenting Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochemistry. 2011;50:10275–10283. doi: 10.1021/bi2014954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cockrell A.L., McCormick S.P., Moore M.J., Chakrabarti M., Lindahl P.A. Mössbauer, EPR, and modeling study of iron trafficking and regulation in ΔCCC1 and Ccc1p-up Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochemistry. 2014;53:2926–2940. doi: 10.1021/bi500002n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nguyen T.Q., Dziuba N., Lindahl P.A. Isolated Saccharomyces cerevisiae vacuoles contain low-molecular-mass transition-metal polyphosphate complexes. Metallomics. 2019;11:1298–1309. doi: 10.1039/c9mt00104b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ogawa N., DeRisi J., Brown P. New components of a system for phosphate accumulation and polyphosphate metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae revealed by genomic expression analysis. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2000;11:4309–4321. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.12.4309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eskes E., Deprez M.A., Wilms T., Winderickx J. pH homeostasis in yeast; the phosphate perspective. Curr. Genet. 2018;64:155–161. doi: 10.1007/s00294-017-0743-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trilisenko L., Tomashevsky A., Kulakovskaya T., Kulaev I. V-ATPase dysfunction suppresses polyphosphate synthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Folia Microbiol. 2013;58:437–441. doi: 10.1007/s12223-013-0226-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tomaschevsky A., Ryasanova L., Kulakovskaya T., Kulaev I. Inorganic polyphosphate in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae with a mutation disturbing the function of vacuolar ATPase. Biochemistry (Moscow) 2010;75:1052–1054. doi: 10.1134/s0006297910080158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamaguchi-Iwai Y., Stearman R., Dancis A., Klausner R.D. Iron-regulated DNA binding by the AFT1 protein controls the iron regulon in yeast. EMBO J. 1996;15:3377–3384. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rutherford J.C., Ojeda L., Balk J., Muhlenhoff U., Lill R., Winge D.R. Activation of the iron regulon by the yeast Aft1/Aft2 transcription factors depends on mitochondrial but not cytosolic iron-sulfur protein biogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:10135–10140. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413731200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lesuisse E., Santos R., Matzanke B.F., Knight S.A.B., Camadro J.M., Dancis A. Iron use for haeme synthesis is under control of the yeast frataxin homologue (Yfh1) Hum. Mol. Genet. 2003;12:879–889. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miao R., Martinho M., Morales J.G., Kim H., Ellis E.A., Lill R., Hendrich M.P., Münck E., Lindahl P.A. EPR and Mössbauer spectroscopy of intact mitochondria isolated from Yah1p-depleted Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochemistry. 2008;47:9888–9899. doi: 10.1021/bi801047q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miao R., Kim H., Koppolu U.M.K., Ellis E.A., Scott R.A., Lindahl P.A. Biophysical characterization of the iron in mitochondria from Atm1p-depleted Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochemistry. 2009;48:9556–9568. doi: 10.1021/bi901110n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Milgrom E., Diab H., Middleton F., Kane P.M. Loss of vacuolar proton-translocating ATPase activity in yeast results in chronic oxidative stress. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:7125–7136. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608293200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Diab H.I., Kane P.M. Loss of vacuolar H+-ATPase (V-ATPase) activity in yeast generates an iron deprivation signal that is moderated by induction of the peroxiredoxin TSA2. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:11366–11377. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.419259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eide D.J., Bridgham J.T., Zhao Z., Mattoon J.J. The vacuolar H+-ATPase of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is required for efficient copper detoxification, mitochondrial function, and iron-metabolism. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1993;241:447–456. doi: 10.1007/BF00284699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Supek F., Supekova L., Nelson N. Features of vacuolar H+-ATPase revealed by yeast suppressor mutants. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:26479–26485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hughes C.E., Coody T.K., Jeong M.Y., Berg J.A., Winge D.R., Hughes A.L. Cysteine toxicity drives age-related mitochondrial decline by altering iron homeostasis. Cell. 2020;180:296–310. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.12.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Horie T., Kawamata T., Matsunami M., Ohsumi Y. Recycling of iron via autophagy is critical for the transition from glycolytic to respiratory growth. J. Biol. Chem. 2017;292:8533–8543. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.762963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yuan D.S., Dancis A., Klausner R.D. Restriction of copper export in Saccharomyces cerevisiae to a late Golgi or post-Golgi compartment in the secretory pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:25787–25793. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.41.25787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Winter G., Cordente A.G., Curtin C. Formation of hydrogen sulfide from cysteine in Saccharomyces cerevisiae BY4742: genome wide screen reveals a central role of the vacuole. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Outten C.E., Falk R.L., Culotta V.C. Cellular factors required for protection from hyperoxia toxicity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem. J. 2005;388:93–101. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thorpe G.W., Fong C.S., Alic N., Higgins V.J., Dawes 1. W. Cells have distinct mechanisms to maintain protection against different reactive oxygen species: oxidative-stress-response genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101:6564–6569. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305888101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davis-Kaplan S.R., Ward D.M., Shiflett S.L., Kaplan J. Genome-wide analysis of iron-dependent growth reveals a novel yeast gene required for vacuolar acidification. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:4322–4329. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310680200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yadav J., Muend S., Zhang Y.Q., Rao R.J. A phenomics approach in yeast links proton and calcium pump function in the Golgi. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2007;18:1480–1489. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-11-1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hughes A.L., Gottschling D.E. An early age increase in vacuolar pH limits mitochondrial function and lifespan in yeast. Nature. 2012;492:261–265. doi: 10.1038/nature11654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lindahl P.A., Morales J.G., Miao R., Holmes-Hampton G. Isolation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae mitochondria for Mössbauer, EPR, and electronic absorption spectroscopic analyses. Methods Enzymol. 2009;456:267–285. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)04415-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morales J.G., Holmes-Hampton G.P., Miao R., Guo Y.S., Munck E., Lindahl P.A. Biophysical characterization of iron in mitochondria isolated from respiring and fermenting yeast. Biochemistry. 2010;49:5436–5444. doi: 10.1021/bi100558z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holmes-Hampton G.P., Jhurry N.D., McCormick S.P., Lindahl P.A. Iron content of Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells grown under iron-deficient and iron-overload conditions. Biochemistry. 2013;52:105–114. doi: 10.1021/bi3015339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hudder B.N., Morales J.G., Stubna A.A., Münck E., Hendrich M.P., Lindahl P.A. Electron paramagnetic resonance and Mössbauer spectroscopy of intact mitochondria from respiring Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2007;12:1029–1053. doi: 10.1007/s00775-007-0275-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Park J., McCormick S.P., Cockrell A.L., Chakrabarti M., Lindahl P.A. High-spin ferric ions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae vacuoles are reduced to the ferrous state during adenine-precursor detoxification. Biochemistry. 2014;53:3940–3951. doi: 10.1021/bi500148y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Raguzzi F., Lesuisee E., Crichton R.R. Iron storage in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 1988;231:253–258. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(88)80742-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Singh A., Kaur N., Kosman D.J. The metalloreductase Fre6p in Fe-Efflux from the yeast vacuole. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:28619–28626. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703398200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schafer F.Q., Buettner G.R. Redox environment of the cell as viewed through the redox state of the glutathione disulfide/glutathione couple”. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2001;30:1191–1212. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00480-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martínez-Pastor M.D., Perea-García A., Puig S. Mechanisms of iron sensing and regulation in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017;33:74–75. doi: 10.1007/s11274-017-2215-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Petrezselyova S.K., Zahradka J., Sychrova H. Saccharomyces cerevisiae BY4741 and W303-1A laboratory strains differ in salt tolerance. Fungal Biol. 2010;114:144–150. doi: 10.1016/j.funbio.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zadrag-Tecza R., Kwolek-Mirek M., Bartosz G., Bilinkski T. Cell volume as a factor limiting the replicative lifespan of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biogerontology. 2009;10:481–488. doi: 10.1007/s10522-008-9192-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ohya Y., Umemoto N., Tanidal I., Ohtag A., Iida H., Anraku Y. Calcium-sensitive cls mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae showing a pet- phenotype are ascribable to defects of vacuolar membrane H-ATPase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:13971–13977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Trilisenko L., Zvonarev A., Valiakhmetov A., Penin A., Eliseeva I., Ostroumov V., Kulakovskiy I., Kulakovskaya T. The reduced level of inorganic polyphosphate mobilizes antioxidant and manganese-resistance systems in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cells. 2019;8:1–15. doi: 10.3390/cells8050461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jensen L., Ajua-Alemanji M., Culotta V. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae high affinity phosphate transporter encoded by PHO84 also functions in manganese homeostasis. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:42036–42040. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307413200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moore M.J., Wofford J.D., Dancis A., Lindahl P.A. Recovery of mrs3Δmrs4Δ Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells under iron sufficient conditions and the role of Fe580. Biochemistry. 2018;57:672–683. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.7b01034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wofford J.D., Lindahl P.A. A mathematical model of iron import and trafficking in wild-type and Mrs3/4ΔΔ yeast cells. BMC Syst. Biol. 2019;13:1–16. doi: 10.1186/s12918-019-0702-2. 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Longtine M.S., Demarini D.J., Shah N.G., Wach A., Brachat A., Philippsen P., Pringle J.R. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1998;14:953–961. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199807)14:10<953::AID-YEA293>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gietz R.D., Schiestl R.H., Willems A.R., Woods R.A. Studies on the transformation of intact yeast cells by the LiAc/SS-DNA/PEG procedure. Yeast. 1995;11:355–360. doi: 10.1002/yea.320110408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pierik A.J., Netz D.J.A., Lill R. Analysis of iron–sulfur protein maturation in eukaryotes. Nat. Protoc. 2009;4:753–766. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fansler B., Lowenstein J.M. Aconitase from pig heart. Methods Enzymol. 1969;13:26–30. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nguyen T.Q., Kim J.E., Brawley H.N., Lindahl P.A. Chromatographic detection of low-molecular-mass metal complexes in the cytosol of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Metallomics. 2020;12:1094–1105. doi: 10.1039/c9mt00312f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bryan A., Goranov A., Amon A., Manalis S. Measurement of mass, density, and volume during the cell cycle of yeast. PNAS. 2010;107:999–1004. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901851107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data except those described as “Data not shown” in the text are contained within the manuscript and SI.