Abstract

Acute necrotising diabetic foot (DF) infections are common, costly, and do not infrequently result in debilitating major lower‐extremity amputations. Dakin's solution is a long‐standing topical antiseptic that has shown benefit in this clinical setting, but its use is undermined by a presumed risk of cytotoxicity. In this single‐centre case series, we retrospectively evaluated 24 patients with severe necrotising DF infections treated with a cyclical instillation of Dakin's solution at a referral multidisciplinary DF unit. Most patients achieved favourable outcomes in infection control and limb salvage, with only one patient (4.2%) requiring a major (at or above‐the‐ankle) amputation. The mean time to complete or near‐complete wound granulation was 5.4 weeks. Of the 12 patients who completed 12 or more months of longitudinal follow up, only 2 (12.2%) had a wound recurrence. In this severe DF infection patient cohort, Dakin's solution led to a clinically meaningful improvement. No remarkable impairment in the wound‐healing process was observed.

Keywords: amputation, Dakin's solution, diabetes complication, diabetic foot, diabetic foot ulcer

1. INTRODUCTION

Among the plethora of serious diabetes‐related complications, the diabetic foot (DF) is one of the most common, disabling, and costly, which persists as the most frequent cause of non‐traumatic lower‐extremity amputation (LEA). Major (at or above‐the‐ankle) LEAs are a particular catastrophic event, demonstrating an 80% higher mortality than minor amputations and a median survival of only 1.9 years.1 Major LEAs also result in profound consequences to the health‐related quality of life of the patient and his or her family and caregivers,2, 3 is a source of psychological distress and scarring,4 and preludes exceptionally high health care expenditures and homecare costs.5, 6 Unfortunately, preventing this unwarranted outcome is often exceptionally challenging because of a constellation of several factors, such as the aggressive and necrotising infection course, compromised arterial supply, patient's comorbidities, and delay in seeking medical care. Moreover, attempts to prevent major LEAs are undermined by the scarcity of evidence‐based wound care regimens to treat necrotising infected DFs.

Diluted sodium hypochlorite, mostly known as Dakin's solution (DS), is a topical antiseptic first introduced to address World War I battle wounds.7 Its time‐honoured effectiveness, low cost, and wide availability have kept the solution in use to manage infected wounds.8, 9, 10, 11, 12 Nevertheless, concerns regarding its cytotoxicity and disputes over its effectiveness, coupled with dearth of evidence beyond limited clinical reports, led to several recommendations for its dismissal from the modern wound care armamentarium.13 Whether this concern is valid in real‐word practice remains debatable.

We aim to evaluate our experience with the use of DS in treatment of acutely infected and necrotic DFs.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design and data retrieval

We conducted a single‐centre case series study in a multidisciplinary DF unit, hosted at one of the largest university hospitals in the country. All electronic health records and photographic archives of the DF patients hospitalised at the Unit between January 2016 and June 2019 were collected and reviewed for the exposure of interest. If considered eligible, data from the patient's post‐discharge follow‐up visits in the outpatient DF clinic were also reviewed and retrieved.

2.2. Study population

We identified all adult patients hospitalised with severe DF infections, for which Dakin's solution was used for treatment during the mentioned 38‐month period. A variety of solution concentrations is available, ranging from 0.5% (full strength) to several dilutions (0.25%, 0.125%, and below), and we consistently used the stronger concentrations (0.5% and 0.25%) in almost all the presented cases. All patients otherwise received the best multidisciplinary treatment according to the DF Unit protocol. Collected variables included patients' relevant comorbidities (chronic kidney disease (CKD) with a glomerular filtration rate < 30 mL/min/m2, coronary heart disease (CHD), past stroke, and past major diabetes‐related limb amputation) and details relevant to the DF: “site” on the foot; “extent,” defined by wound length and width; “depth” of the wound; “neuropathy,” studied by a 10‐g monofilament in different places of the foot; “infection,” confirmed by correlation of clinical, bacteriological, histopathological, or imaging studies, as well as intraoperative findings; and time when complete or near‐complete granulation was achieved. The first microbiological isolate (at patient's admission) was also collected. Variables from the follow up in the outpatient clinic registries were also collected and analysed, including the last patient visit and recurrence date (if any).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Characteristics of the patients

We retrieved data of 485 DF patients hospitalised in the mentioned period, of which 27 (5.7%) initiated and/or completed treatment with DS. Of these, three were excluded: one was discharged against medical advice, and two died soon after admission because of systemic complications (septic shock and massive pulmonary embolism, respectively) and thus completed <1 week of treatment with DS.

A total of 24 patients were considered eligible for analysis. Of the 24 patients, 14 (58.3%) were male and 10 (41.7%) female. The mean age was 66 years (40‐82), and the mean number of diabetes‐related comorbidities (other than DF) was three: by prevalence, CHD (58.3%), advanced CKD (58.3%), stroke (33.3%), and DF‐related prior major amputation (20.8%). Detailed descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of diabetic foot patients treated with Dakin's solution during the study period

| Patient | Sex | Age | Patient's comorbidities | Diabetic foot ulcer characteristics | Revasc | Final outcome | Time to granulation | Closure | Last follow‐up (months) | TUR (months) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHD | CKDa | Stroke | Ocular | PMA | Site | Extent | Depth | Neuropathy | Infection | Ischemia | SINBADa | |||||||||

| DS‐treated patients | ||||||||||||||||||||

| I | F | 58 | ‐ | x | ‐ | x | ‐ | Midfoot | 9 × 9 | bone | ‐ | OM + SIR | ‐ | 4 | ‐ | 1 toe | 5 | skin graft | >24 | None |

| II | M | 60 | ‐ | x | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Midfoot | 18 × 7 | bone | x | OM | x | 6 | failure | 3 toes | 4 | Sec. Heal. | 20 | 12 |

| III | F | 82 | x | ‐ | x | x | ‐ | Forefoot | 10 × 4 | bone | x | OM | x | 5 | yes | 2 toes | 8 | Sec. Heal. | 12 | None |

| IV | M | 53 | x | x | ‐ | x | ‐ | Entire foot | 22 × 7 | bone | x | OM | x | 6 | recused | 2 toes | 8 | skin graft | 12 | None |

| VI | M | 53 | x | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Forefoot | 6 × 3 | bone | x | OM | x | 4 | failure | 1 toe | 5 | DPC | 12 | None |

| VI | M | 76 | x | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Midfoot | 4 × 3 | bone | ‐ | OM + SIR | x | 3 | failure | 1 toe | 6 | Sec. Heal. | Lost to follow up | Lost to follow up |

| VII | M | 60 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | x | ‐ | Forefoot | 15 × 4 | joint | ‐ | SA | x | 3 | yes | None | 3 | DPC | >24 | None |

| VIII | M | 75 | ‐ | x | ‐ | x | ‐ | Forefoot | 12 × 5 | bone | x | OM + SIRS | x | 4 | yes | 1 toe | 7 | DPC | Lost to follow up | Lost to follow up |

| IX | F | 40 | x | x | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Forefoot | 9 × 3 | bone | x | OM | x | 4 | yes | 1 toe | 6 | Sec. Heal. | >24 | 12 |

| X | F | 75 | ‐ | x | x | x | ‐ | Midfoot | 22 × 10 | bone | x | OM + SIRS | x | 6 | yes | TMA | 7 | skin graft | 12 | None |

| XI | F | 73 | x | x | ‐ | x | x | Forefoot | 7 × 9 | bone | x | OM + SIRS | x | 4 | yes | 4 toes | 9 | Sec. Heal. | >24 | None |

| XII | M | 70 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | x | x | Forefoot | 7 × 10 | bone | x | SA | x | 4 | yes | TMA | 7 | Sec. Heal. | 15 | None |

| XIII | F | 64 | ‐ | x | ‐ | x | x | Forefoot | 11 × 4 | Fascia | ‐ | SF | x | 3 | yes | 2 toes | 4 | Sec. Heal. | Lost to follow up | Lost to follow up |

| XIV | F | 69 | x | ‐ | x | x | ‐ | Midfoot | 4 × 6 | bone | x | OM | x | 5 | yes | 2 | 3 | Sec. Heal. | 6 | Chronic ulcer |

| XV | F | 81 | ‐ | ‐ | x | x | ‐ | Midfoot | 5 × 5 | bone | x | OM | x | 5 | yes | None | 3 | Sec. Heal. | >24 | None |

| XVI | M | 56 | x | x | ‐ | x | x | Hindfoot | 12 × 7 | bone | x | OM | x | 5 | yes | 2 toes | 6 | DPC | 6 | None |

| XVII | M | 70 | x | x | ‐ | x | ‐ | Midfoot | 11 × 9 | bone | x | SA | x | 6 | yes | TMA | 7 | Sec. Heal. | 10 | None |

| XVIII | F | 80 | x | x | x | x | Midfoot | 14 × 6 | bone | x | OM + SIR | ‐ | 5 | ‐ | 4 toes | 5 | Skin graft | 6 | None | |

| XIX | M | 65 | ‐ | ‐ | x | ‐ | x | Forefoot | 2 × 2 | bone | ‐ | OM | x | 3 | yes | None | 5 | Sec. Heal. | 3 | None |

| XX | M | 76 | x | x | x | ‐ | ‐ | Forefoot | 15 × 3 | bone | x | OM | x | 4 | yes | 4 toes | 4 | Sec. Heal. | 3 | None |

| XXI | M | 46 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | x | ‐ | Forefoot | 12 × 5 | bone | x | OM | ‐ | 3 | ‐ | 3 toes | 4 | Sec. Heal. | 3 | None |

| XXII | M | 68 | x | x | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Midfoot | 19 × 10 | bone | x | OM + SIR | x | 6 | yes | Major | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| XXIII | M | 66 | x | x | ‐ | x | ‐ | Forefoot | 5 × 2 | joint | x | SA+ SIRS | x | 4 | Failure | None | 6 | DPC | >24 | None |

| XXIV | F | 68 | x | ‐ | x | ‐ | ‐ | Midfoot | 4 × 4 | bone | ‐ | OM | x | 4 | ‐ | 2 toes | 3 | Sec. Heal. | Lost to follow up | Lost to follow up |

| DS‐treated patients ineligible for analysis | ||||||||||||||||||||

| I | M | 68 | ‐ | x | ‐ | x | ‐ | Midfoot | 11 × 6 | Fascia | ‐ | SF + SIRS | x | 5 | N/A |

Death (septic shock) |

N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| II | M | 61 | x | x | x | x | x | Forefoot | 5 × 4 | bone | x | SF + SIRS | x | 4 | N/A |

Death (PE) |

N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| III | F | 49 | x | ‐ | x | ‐ | ‐ | Forefoot | 2 × 5 | joint | x | SA | ‐ | 3 | N/A | Discharged AMA | N/A | N/A | Lost to follow up | Lost to follow up |

Note: To avoid intra‐ and inter‐observer subjectivity, the main outcome measure used (“Final outcome”) was amputation, classified as: none, minor (one to five toes or transmetatarsal amputation) or major (all amputations at or above the ankle).

Abbreviations: AMA, against medical advice; CHD, coronary heart disease; CKD, advanced chronic kidney disease (glomerular filtration rate < 30 mL/min/m2); DPC, delayed pulmonary closure; DS, Dakin's solution; N/A, not applicable; OM, osteomyelitis; PE, pulmonary embolism; Revasc, Revascularisation; SA, septic arthritis; Sec. Heal., secondary healing;; SF, septic fasciitis; SIRS, systemic inflammatory response syndrome; TMA, transmetatarsal amputation.

SINBAD (Site, Ischaemia, Neuropathy, Bacterial Infection, and Depth) score.

3.1.1. DF characteristics

DF wounds had a mean length of 10.6 (2‐22) cm and a mean width of 5.7 (2‐10) cm. The ulcers were deep, and most presented osteomyelitis as 21 (87.5%) had exposed bone and 19 (79.2%) had definitive evidence of bone infection. Nine patients (33.3%) met sepsis criteria. Most DFs were neuropathic and/or ischaemic. Neuropathy was present in 18 (75%) DF patients. On the other hand, ischaemia was observed in 21 patients (87.4%), of which 15 (71.4%) underwent successful revascularisation. Altogether, the mean SINBAD score was 4.375 (3‐6).

3.2. Microbiological isolates

Methicillin‐sensitive Staphylococcus aureus was the most frequent isolate (25%) in DF wounds before DS treatment was initiated. Other common isolates were the Streptococcus agalactiae, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli (one extended spectrum beta lactamase [ESBL] producer), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (12.5% each). Co‐infections (more than one infective isolate in the same culture) were identified in nine (37.5%) cases. Details regarding the isolates by case are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Microbiological isolates of diabetic foot wounds at admission

| Patient | Gender | Age | Microbiological isolates |

|---|---|---|---|

| DS‐treated patients eligible for analysis | |||

| I | F | 58 | Streptococcus anginosus/MSSA |

| II | M | 60 | Klebsiella pneumoniae, Enterococcus faecalis |

| III | F | 82 | MRSA |

| IV | M | 53 | MRSA/ ESBL‐producer Escherichia coli /Enterococcus faecalis |

| V | M | 53 | MSSA |

| VI | M | 76 | MSSA |

| VII | M | 60 | MSSA |

| VIII | M | 75 | Streptococcus agalactiae/MSSA |

| IX | F | 40 | Proteus mirabilis/Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

| X | F | 75 | Streptococcus agalactiae |

| XI | F | 73 | Citrobacter freundii, proteus vulgaris |

| XII | M | 70 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

| XIII | F | 64 | Streptococcus agalactiae |

| XIV | F | 69 | Enterobacter cloacae/Achromobacter xylosoxidans ssp xylosoxidans |

| XV | F | 81 | Proteus mirabilis |

| XVI | M | 56 | Morganella morganii |

| XVII | M | 70 | Polymicrobial |

| XVIII | F | 80 | Escherichia coli, Enterococcus faecalis |

| XIX | M | 65 | Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli |

| XX | M | 76 | MSSA |

| XXI | M | 46 | Klebsiella pneumoniae |

| XXII | M | 68 | Proteus penneri, Morganella morganii |

| XXIII | M | 66 | Polymicrobial |

| XXIV | F | 68 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

| DS‐treated patients ineligible for analysis | |||

| I | M | 68 | Enterobacter cloacae/Achromobacter xylosoxidans ssp xylosoxidans/MRSA |

| II | M | 61 | Polymicrobial |

| III | F | 49 | Polymicrobial |

Abbreviations: DS, Dakin's solution; ESBL, extended spectrum beta lactamase; MRSA, methicillin‐resistant staphylococcus aureus; MSSA, methicillin‐sensitive staphylococcus aureus.

3.2.1. DF treatment and outcome

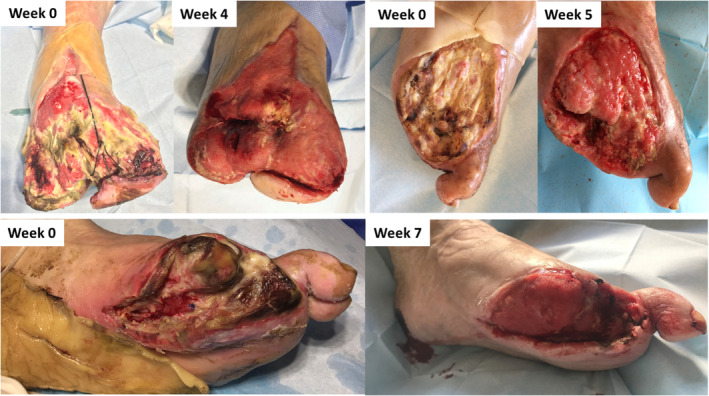

Limb salvage was successful in all except one patient, who required major amputation because of rapidly progressing septic gangrene. A total of 19 patients (79.2%) had at least one minor amputation: one to four toes in 16 patients and a transmetatarsal amputation in the other three (12.5%) patients. The remaining four patients (16.7%) recovered successfully without any major or minor amputation. The mean time to complete or near‐complete wound granulation was 5.4 weeks (3‐9). Healing by secondary intention was used in 14 patients (58.3%), followed by repair techniques such as delayed primary closure in five patients (20.8%) and split‐thickness skin grafting in four patients (16.7%). No major adverse events related to the DS instillation technique were noted. Pre‐ and post‐treatment outcomes can be observed in Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1.

Wounds treated with Dakin's solution (before/after)

Figure 2.

Wounds treated with Dakin's solution (before/after)

Considering the 12 patients who had more than 12 months of follow up at the last clinic visit, only two (12.2%) had a recurrence of a DF wound. A significant proportion of patients were lost to follow up (16.7%).

4. DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest study regarding the use of DS in the management of infected DFs. In this clinical setting, periodic instillation of DS appears beneficial for infection control and limb salvage as exhibited by a single occurrence of major LEA (4.2%) and low rate of 12‐month recurrences (12.2%) in this DF ulcer cohort, distinct for their remarkable severity and risk at admission for major LEA.

DS has a long‐standing history in the treatment of infected wounds. Its main interest relies on its potent debridement and its antiseptic proprieties, making it an attractive option to address heavily contaminated wounds with a large burden of necrotic tissue, in which the debris acts as privileged reservoirs for a high load of infective pathogens. DS has also shown superiority to other topical antiseptics in neutralising multidrug‐resistant bacteria,14 which are increasingly found in DF wounds15, 16 and probably contribute to worse outcomes. Indeed, co‐infections are fairly frequent in our presented DF population, and a significant number is known for their antibiotic resistances, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, ESBL‐producing E. coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and others (Table 2). To date, no acquired resistance mechanisms to DS are known,17 a useful advantage in this era of emerging antibiotic resistances. In addition, DS is a short‐lived antiseptic solution, which needs frequent daily reapplications, ideally three to four times a day. This inconvenience may in fact be advantageous as it helps to maintain a wet environment in the wound bed and thus facilitate the biologic healing process. In our practice, we leave two sterile butterflies (also known as winged infusion set) enveloped in the secondary dressing: while the needle tip stays near the wound bed, the proximal edge (the connector) remains external to the dressing, as shown in Figure 3. With this simple technique, DS can be easily instilled into the wound without the need to redo the dressing many times a day (which is more time and resource consuming).

Figure 3.

Dakin's solution (DS) instillation system. Black arrow pointing to the two connectors which are left externally. Periodic instillation of DD is thus easily performed without the need to manipulate the dressing

In spite of the accumulated favourable experience since its first use in World War I, where thousands of lives were saved by this solution in a pre‐antibiotic era,7 DS continues to be a controversial agent. Some entities have strongly discouraged its use in wound care,13 especially because of its presumed cytotoxicity to healthy tissues, an observation mostly seen in laboratorial investigations. Nevertheless, this debatable yet relevant concern has not been definitely substantiated by in vivo studies17 and has especially not been significantly observed in real‐world clinical practice, where several successful reports regarding the medical use of DS have been published.8, 9, 10, 11, 12 Extremely inflammatory and infected human wounds create a dynamic complex environment that is difficult to replicate with precision in the laboratory, which at least partially justifies the disagreement in the laboratory and real‐world clinical practice with regard to observed cytotoxicity. For example, open wounds contain a myriad of components (serum, pus, necrotic debris) that probably mitigate the potential toxicity of DS.18

As always, adequate patient selection and treatment attitude is critical for optimal risk/benefit. First, most patients do not present with extreme cases requiring treatment with DS as shown by its infrequent use in our cohort (less than 6% of all cases). Second, treatment is always initiated after the non‐aggressive surgical debridement (as required). Third, wound care is a dynamic process: once the wound bed is cleared of infection and necrotic debris, DS concentration can be reduced or stopped, and another local treatment of the clinician's choice may be attempted, if needed, which will also soften the transition from the inpatient to outpatient care. Fourth, DS is a common cause of irritant contact dermatitis, but this adverse effect is often mild and is easily managed or avoided with cutaneous protection (with a hydrocolloid dressing) and symptomatic care (with moisturisers and topical steroids). Finally, a multidisciplinary approach to an infected DF is of paramount importance. Systemic antibiotics, revascularisation (when indicated), offloading of the foot and adequate medical support for acute organ injuries, metabolic dysregulation, and other comorbidities should never be neglected if the best outcome possible is to be achieved, justifying the need for a multidisciplinary unit in DF care.

Our design has several limitations, including its single‐centre, observational, retrospective nature devoid of a comparator. It is also not possible to exclude residual confounding. Nevertheless, this study adds significant evidence to the paucity of knowledge regarding treatments for infected DF management. Further studies with larger prospective data are warranted to further support the approach and identify criteria for adequate DF patient selection. Future research should also focus on the combination of vacuum‐assisted closure with DS instillation, which might provide synergic advantages in these complex cases.

In conclusion, in this single‐centre patient cohort, we found DS to be an effective adjuvant agent in the treatment of severe DF infected wounds. DS was well tolerated, and no significant detrimental effects in the wound healing mechanisms were observed.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no potential conflict of interest.

Duarte B, Formiga A, Neves J. Dakin's solution in the treatment of severe diabetic foot infections. Int Wound J. 2020;17:277–284. 10.1111/iwj.13268

REFERENCES

- 1. Huang Y, Lin C, Yang H, Hung S, Chen I. Survival and associated risk factors in patients with diabetes and amputations caused by infectious foot gangrene. J Foot Ankle Res. 2018;11(1):1‐7. 10.1186/s13047-017-0243-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sothornwit J, Srisawasdi G, Suwannakin A, Sriwijitkamol A. Decreased health‐related quality of life in patients with diabetic foot problems. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2018;11:35‐43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pé Diabético Neves J., Uma Visão Prática. Lisbon: Schülke; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pedras S, Preto I, Carvalho R, Pereira MG. Traumatic stress symptoms following a lower limb amputation in diabetic patients : a longitudinal study. Psychol Health. 2019;34(5):535‐549. 10.1080/08870446.2018.1545907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tchero H, Kangambega P, Lin L, et al. Cost of diabetic foot in France, Spain, Italy, Germany and United Kingdom : a systematic review. Ann Endocrinol (Paris). 2017;79(2):67‐74. 10.1016/j.ando.2017.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Boulton AJM, Vileikyte L, Ragnarson‐tennvall G, Apelqvist J. The global burden of diabetic foot disease. Lancet. 2005;366:1719‐1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Georgiadis J, Nascimento VB, Donat C, Okereke I, Shoja MM, Dakin HD. Dakin's solution: “one of the most important and far‐reaching contributions to the armamentarium of the surgeons”. Burns. 2019;45(7): 1509‐1517. 10.1016/j.burns.2018.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lewandowski LTL, Usn MC, Purcell CPTR, et al. The use of dilute Dakin's solution for the treatment of Angioinvasive fungal infection in the combat wounded : a case series. Mil Med. 2013;178:503‐508. 10.7205/MILMED-D-12-00322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Milner SM, Heggers JP. The use of a modified Dakin's solution (sodium hypochlorite ) in the treatment of Vibrio vulnificus infection. Wilderness Environ Med. 1999;10(1):10‐12. 10.1580/1080-6032(1999)010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Degnim AC, Scow JS, Hoskin TL, Joyce P, Patel R, Baddour LM. Randomized controlled trial to reduce bacterial colonization of surgical drains after breast and axillary operations. Ann Surg. 2013;258(2):240‐247. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31828c0b85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Altunoluk B, Resim S, Efe E, et al. Fournier's gangrene : conventional dressings versus dressings with Dakin's solution. ISRN Urol. 2012;2012:1‐4. 10.5402/2012/762340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Duarte B, Cabete J, Formiga A, Neves J. Dakin's solution : is there a place for it in the 21st century ? Int Wound J. 2017;14(6):918‐920. 10.1111/iwj.12728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Feridas GA de I em . Parecer técnico sobre a utilização de Hipoclorito de Sódio (apresentação soluto de Dakin). 2010.

- 14. Neely AN, Gardner J, Durkee P, et al. Are topical antimicrobials effective against bacteria that are highly resistant to systemic antibiotics? J Burn Care Res. 2009;30:19‐29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Henig O, Pogue JM, Cha R, et al. Epidemiology of diabetic foot infection in the metro‐Detroit area with a focus on independent predictors for pathogens resistant to recommended empiric antimicrobial therapy. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2018;5(11):1‐9. 10.1093/ofid/ofy245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cabete J, Moniz L, Pinto M, Neves J, Pereira A. Caracterização do perfil microbiológico e de sensibilidade antimicrobiana dos microrganismos isolados em úlceras diabéticas de um hospital português. Rev Por Cir CardioToracica e Vasc. 2011;18:53‐60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cotter JL, Fader RC, Lilley C, Herndon DN. Chemical parameters, antimicrobial activities, and tissue toxicity of 0.1 and 0.5% sodium hypochlorite solutions. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1985;28(1):118‐122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Vick LR, Propst R, Bozeman R, Wysocki AB, Ph D. Effect of Dakin's solution on components of a dermal equivalent. J Surg Res. 2009;155(1):54‐64. 10.1016/j.jss.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]