Abstract

Active involvement of patients in planning, conducting, and disseminating research has been adopted by many organisations internationally, but the extent to which this occurs in surgical wound care is not evident. This scoping review aimed to identify how patients have been involved in surgical wound care research and the quality of its reporting. Full‐text studies focused on preoperative and postoperative surgical wound care in the acute care setting, published in English between 2004 and 2019, were included in the review. Screening, data charting, and quality assessment were conducted by two reviewers independently, adjudicated by a third, and then reviewed by five others. Thematic analysis synthesised the findings. Of the eight included studies, seven explained the methods for patient involvement and five described aims related to patient involvement and commented on patient involvement in the discussion. None met all of the quality assessment criteria. Three themes emerged: involvement in modifying and refining research processes, connecting and balancing expert and patient views, and sharing personal insights. Recommendations to improve patient involvement in surgical wounds research include the following: using framework and tools to inform future research; training researcher and patients in their respective research roles; and ongoing monitoring of patient involvement.

Keywords: consumer involvement, patient participation, research, surgical wounds, systematic review

1. INTRODUCTION

Active involvement of patients in planning, conducting, and disseminating research has a groundswell of support. Governments and their funding bodies, 1 , 2 , 3 consumer groups, 4 researchers, 5 , 6 , 7 and research groups such as the Cochrane Collaboration 8 have recognised the benefits of patient input. Patient and public involvement in research is defined as research being carried out “with” or “by” patients and members of the public, rather than “to,” “about,” or “for” them. 9 Several other terms used to capture patient involvement include patient and/or public advisors, representatives or partners, patient and public involvement, and consumers and community involvement. 10 , 11 , 12 Patients can provide valuable insights and positively influence research priorities, study design and conduct, refine research questions, interventions, comparators and study outcomes, and improve broader processes such as recruitment and dissemination. 11 , 13 , 14 Nevertheless, optimal ways of obtaining patient input are yet to be ascertained. 15 , 16 , 17

Patient involvement can be embedded across the research continuum, including within the planning, conducting, and dissemination phases. 18 A recent systematic review identified 65 theoretically diverse frameworks for supporting, evaluating, and reporting patient involvement in research. 10 Other reviews of patient involvement in research have specific foci such as on research priority setting, in clinical trials, and in engaging hard‐to‐reach patients. 16 , 19 Work has also been undertaken to assess patient involvement in research undertaken by various specialty groups such as cancer 20 and more broadly on health and social care research. 15 , 21

Surgical procedures are a cornerstone of health care systems with an estimated 4511 operations per 100 000 population occurring annually worldwide, equating to one surgical procedure each year for every 22 people. 22 Surgical wounds are created by an incision using sharp cutting instruments, such as a scalpel and may be closed by either primary (ie, sutures, staples) or secondary intention (ie, wound left open). 23 Given the high volume of surgical procedures and the potential burden that wound complications such as surgical site infections have for patients and their families, it seems intuitive that patients will have a vested interest in surgical wound care research. Yet, the extent of their input and involvement in it is not evident. A systematic review explored the quality of reporting of patient and public involvement in surgical research, but it specifically examined surgical procedures exclusively. 5 Thus, we aimed to extend this understanding by synthesising the research evidence on patient input into surgical wound care research.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design

This scoping review was conducted using Arksey and O'Malley's scoping review framework, 24 along with recommendations to enhance these steps. 25 A scoping review systematically synthesises evidence to answer exploratory research questions and identifies gaps in research. 26 They identify the breadth of a body of literature on a topic and can be used to map the nature, features, and volume of existing literature on a topic. 24 Our review process comprised five stages: (a) identifying the research questions; (b) searching for and identifying relevant studies; (c) selecting studies; (d) charting the data; and (e) collating, summarising, and reporting the results. Arksey and O'Malley's 24 optional stage for consulting with patients was an embedded feature of the development and conduct of this review, adding both methodological rigour 25 and an essential patient viewpoint. The review was designed and executed to comply with the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA‐ScR) checklist. 27

The Australian National Health and Medical Research Council's and Consumer Health Forum of Australia's definition of a consumer was adopted to define the term patient because it was broad, ensuring the scoping review was not restricted: “patients and potential patients, carers, and people who use health care services” 28 (p. 6). The research process was defined as the steps involved in undertaking research from determining priorities and questions to designing and conducting the study and finally, analysing and disseminating findings. Surgical wound care was defined as any preoperative or postoperative clinical practices associated with a surgical wound, involving a surgical incision and healing by either primary or secondary intention.

2.2. Research questions

Two questions guided this review: (1) How have patients been involved in the conduct of surgical wound care research? and (2) What is the quality of patient involvement and reporting in surgical wound care research? These questions evolved over time, as is common in scoping reviews.

2.3. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

To be eligible, articles had to be full‐text studies, published in English and focused on care of surgical wounds, defined as wounds involving a surgical incision and healing by either primary or secondary intention. 23 There were no restrictions on study design, but the setting was restricted to acute care hospitals. Surgical wound care includes both preoperative and postoperative clinical practices, such as showering, dressing changes, and so on. We included published studies that reported, described, or evaluated patient involvement in surgical wound care research. We excluded studies that only focused on patients as research participants (ie, the collection of their individual data). Studies related specifically to surgical procedures were also excluded because of a recent review on this topic. 5

2.4. Search strategy

A search of five online databases (Ovid MEDLINE, Elsevier Embase, EBSCO CINAHL, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and ProQuest) was undertaken in consultation with an expert health librarian. The search covered a 15‐year period from January 2004 to September 2019. The year 2004 was chosen because it coincided with the release of a model framework for consumer and community participation in health research, 1 the establishment of the James Lind Alliance in the United Kingdom, and Patient‐Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) funded research. 11 Searches took place on 16 September 2019. The reference lists of included papers were manually searched to identify further relevant articles that might meet the inclusion criteria through “ancestry” searches. 29 For practical purposes, grey literature was excluded.

2.4.1. Search terms

The search terms were developed and refined in consultation with an expert health librarian. The search strategy captured terms related to (a) consumer, patient, or public (b); participation, involvement, and advice; and (c) surgical wound. More details about these search terms are provided in Table A1. The full search strategy for Ovid MEDLINE was undertaken on 16 September 2019 and is included as an example in Table A2. The references were managed using Rayyan, a systematic review web application. 30

2.5. Article selection

Two reviewers (RM and JP) independently screened the articles in two stages using title, abstract, and keywords, then full text. Papers which were clearly irrelevant were excluded in the first stage of title and abstract review, and if the eligibility of the paper was not clear, the full text was then reviewed in the second stage. This second stage included a review of the authors, their titles and affiliations, to try to identify patients who may have been part of the research team. Disagreements were resolved through consensus discussions between the two, with adjudication by a third reviewer (WC) when consensus could not be reached. Decisions about which articles to include in the scoping review was an iterative process, 26 guided by researcher familiarity with the literature and refinement of scoping review questions. 24 Regular meetings occurred between three authors (RM, JP, and WC) to ensure rigour in the study selection process. The PRISMA‐ScR 27 flow chart was used to describe the initial search results, studies screened, studies included and excluded, and reasons for exclusion.

2.6. Data charting

The data charting process evolved during the review as the reviewers refined the specific data to be extracted to help answer the review questions. 24 , 26 Extraction tables were piloted on three articles, 26 and subsequently refined, followed by a second pilot extraction phase to develop standardised interpretations and improve interrater reliability. 31 As part of this charting, the methods of involving patients, the time points for this involvement, and the levels of involvement were identified. We used a research adaptation of the International Association of Public Participation spectrum that included six levels of engagement (learn/inform, participate, consult, involve, collaborate lead/support) 32 to classify involvement. The data were initially extracted independently by two reviewers (RM and JP) and then reviewed by a third (WC) and then assessed by other reviewers (EH, RW, EM, FL, and SL) to ensure its authenticity and maintain rigour. The data extraction process was an iterative and involved regular meetings among three reviewers (RM, JP, and WC) and included the broader team as required.

Next, the quality of the reporting of patient involvement was assessed using the Guidance for Reporting Involvement of Patients and the Public (GRIPP2) short form reporting checklist. 6 It is comprised of five reporting criteria: aim, methods, study results, discussion and conclusions, reflections and critical perspectives. Finally, the quality and impact of user involvement in published studies tool 33 (referred to as the critical appraisal criteria) was used in a second assessment of the studies to allow a more detailed analysis of the quality and extent of patient involvement. It has nine items focused on the rationale and appropriateness of involvement as well as methodological and ethical considerations. 33 The data for GRIPP2 and Wright and Foster's 33 critical appraisal criteria were initially extracted by two authors (RM and JP) independently and checked by one other (WC). Following training, the data were reviewed and appraised by at least two other authors (EH, RW, EM, FL, and SL).

2.7. Collating and summarising (data analysis)

Thematic analysis was used to collate and summary the findings. 25 Initial thematic analysis was undertaken by two reviewers (RM and EH), whereby findings from each of the papers were identified, compared, and interpreted inductively until descriptive codes and preliminary themes were generated. 34 Next, an iterative process of collaborative analysis 35 was initiated. Three reviewers (WC, JP, and JC) reviewed the preliminary themes, bringing together analytic perspectives from different disciplines, theoretical traditions and professional/lay expertise, to confirm analytical decisions. A benefit of collaborative analysis is improved intercoder reliability 35 through checking the appropriateness and consistency of coding and preliminary themes.

2.8. Patient involvement

The chair of the local hospital's consumer advisory group (JC) was invited to join the review team, specifically, contributing to the development of the review protocol and undertaking discrete parts of this review including analysis. The extent of her contribution was recording using the GRIPP2 checklist. Given the focus of this scoping review, patient involvement was considered a crucial aspect of the review.

3. RESULTS

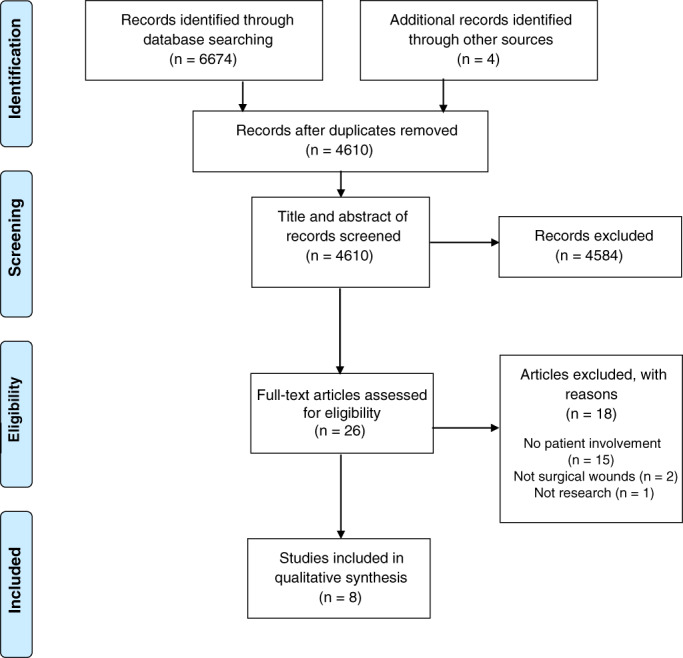

The initial search yielded 6674 articles. The articles were imported into Rayyan and duplicates removed. After title and abstract screening by two reviewers (RM and JP), further 4584 articles were removed, resulting in 26 articles for full‐text review. Following full‐text review, further 18 articles were excluded and 8 articles 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 included in review (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA flow chart of studies 27

3.1. Characteristics of the included studies

Table 1 summarises the eight included studies. Of them, five were conducted in the United States, 36 , 37 , 41 , 42 , 43 and three in the United Kingdom. 38 , 39 , 40 All studies were published between 2013 and 2019. The terms “patient” and “patient advisor” were used in both the US and UK studies to refer to those involved in surgical wound care research, whereas “patient representative” and “patient and public involvement member” (PPI member) were used exclusively in two UK studies, 39 , 40 and “patient advocate” in one US study. 42 The context of the research reflected a wide variety of surgical procedures. One study was qualitative, 38 two were cross‐sectional, 36 , 43 and the remaining five 37 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 were multiple phased, two of which included systematic reviews.

TABLE 1.

Study characteristics (n = 8)

| Reference (country) | Study aim | Design | Surgical context | Population and sample | Funding | Conflict of interest |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anderson et al 36 (United States) | To determine patient awareness and knowledge of risks, consequences, and prevention of SSI | Cross‐sectional survey | Recent surgical procedure | Convenience sample of 50 adult patients at risk of SSI or who were already diagnosed with an SSI | Unknown | No |

| Lee et al 37 (United States) | To gain an understanding of the current application of mHealth and PGHD in postoperative incision management and SSI surveillance | Health technology assessment, including a literature review and key stakeholder interviews | SSI surveillance technology and PGHD postoperative care | 25 interviews with key stakeholders, including two patients with experience in the field of mHealth and PGHD for SSI | Yes | No |

| McCaughan et al 38 (United Kingdom) | To explore patients' views and experiences of living with a surgical wound healing by secondary intention | Qualitative, descriptive design, using semi‐structured, individual interviews | General, vascular, and orthopaedic surgery | 20 patients with open surgical wounds, 11 women and nine men | Yes | No |

| McNair et al 39 (United Kingdom) | To define a core outcome set for studies in colorectal cancer surgery | Consensus methodology—including systematic review, patient interviews, survey, Delphi methods | Rectal (33, 35%), left (34, 35%), and right (30, 29%) colonic tumours |

81 colorectal cancer centres were invited; 63 (78%) responded, including 90 surgeons and 8 clinical nurse specialists Patient response rate was 97 out of 267 invited (36%) |

Yes | Yes a |

| Reeves et al 40 (United Kingdom) | To establish feasibility of an RCT to compare the effectiveness of different dressings or no dressing on SSI following elective surgery and to develop a valid method for the assessment of SSI to be used in the main trial |

Phase A: Case studies with interviews and various surveys Phase B: Pilot RCT, interviews, validation of surveys, health economic analyses |

Elective and unplanned (emergency) abdominal surgeries, healing by primary intention |

Phase A: Interviews: 102 participants (69 HCPs and 33 patients Survey: 727 patients in 20 hospitals Questionnaire refinement: participants, n = 37; HCPs, n = 24 Phase B: Pilot RCT: 394 participants. Acceptability interviews: 55 participants |

Yes | No |

| Sanger et al 41 (United States) | To explore patient experience of SSI and openness to a mobile health wound monitoring “app” as a novel solution | Mixed method design with semi‐structured interviews and surveys | Abdominal surgery | 13 English speaking adult patients who had postdischarge wound complications after undergoing an intra‐abdominal operation | Yes | No |

| Sanger et al 42 (United States) | To examine conflicts, tensions, and agreements in the course of designing a novel, patient‐centred data collection technology tool for mobile postdischarge surgical wound monitoring | Iterative design process, including semi‐structured interviews, surveys, critical incident technique, and “think‐aloud” approach | Patients who had recently experienced postdischarge SSI in a tertiary academic medical centre and trauma centre | 13 patients who experienced a postdischarge SSI; 6 patient advocates who volunteered to advise the hospital on matters affecting patients; 11 health professionals who had experienced routinely managing postdischarge infections | Yes | No |

| Wiseman et al 43 United States | To explore the feasibility of a mHealth smartphone‐based intervention for wound monitoring to promote early recognition of wound complications after discharge | Cross‐sectional survey | Vascular surgery | 50 adult patients undergoing vascular surgery, not in in intensive care unit | Yes | No |

Abbreviations: HCPs, health care professionals; MDs, medical doctors; mHealth, mobile health; PGHD, patient‐generated health data; RCT, randomised control trial; RNs, registered nurses; SSI, surgical site infection.

Competing interests declared.

3.2. Level of involvement and quality of reporting on patient involvement

Table 2 contains an overview of how patients were involved in the conduct of the studies included in this scoping review. Four studies involved patients at more than one time point. 38 , 39 , 40 , 42 In terms of the involvement spectrum, 32 four studies consulted, 36 , 37 , 41 , 43 one involved, 38 and two collaborated 39 , 42 with patients. We were unable to determine this information for one study. 40 Based on the GRIPP2, the quality of reporting on patient involvement in the studies was found to be variable (Table 3). Table A3 provides detailed information about each study's adherence to the GRIPP2. All but one study 41 clearly described the PPI methods, five 38 , 39 , 40 , 42 , 43 described the PPI aims and four described PPI in the discussion and conclusion. 37 , 38 , 40 , 41 Two criteria were less evident, with only three studies 38 , 39 , 40 describing PPI in the results and two studies providing reflections on and a critical perspective on PPI. 40 , 42 Table 4 provides a summary of the research in relation to the critical appraisal criteria. 33 Half of the studies 38 , 39 , 40 , 42 met five of the nine criteria and two studies only met one criterion. 36 , 41 Table A4 provides more detailed information about this analysis. A summary of consumer involvement in development of our review using the GRIPP2 6 is outlined in Table A5.

TABLE 2.

Summary of consumer involvement in the research

| Reference | Consumers | Involvement methods | Time points | Level of involvement 32 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anderson et al 36 | HCWs and 8 patients | Preliminary drafts of the questionnaire were refined with input from HCWs and patients | Single time point, before participant data collection | Consult |

| Lee et al 37 | 2 patients | Key informant interviews with patients. Interviews included in the final evidence synthesis | Single time point, after literature review, before a Health Technology Assessment report finalisation | Consult |

| McCaughan et al 38 | 3 patient advisors | Patient adviser involvement throughout the research. Topic guide for interviews developed and piloted with input from patient advisers. Contribution from patient advisors on data analysis and comments on early draft of study findings | Multiple time points, development, pilot, and results interpretation | Involve |

| McNair et al 39 | 2 patient representatives acknowledged in the paper, and one coauthor appears to be a consumer |

Phase 1: patient representatives were involved in questionnaire domain generation—interviews with patients to inform domains PROMS verified with involvement of one patient questionnaire piloted by patients for face validity, understanding, and acceptability and modified as a result of the feedback Phase 2: patients' essential stakeholders in second Delphi phase Phase 3: consensus meetings with patients, caregivers, and surgeons to finalise the core set |

Multiple time points through research phases 1, 2, and 3, development, pilot, and results interpretation | Collaborate |

| Reeves et al 40 | 1 patient representative | Patient representative on steering committee: two PPI meetings to discuss RCT design and protocol elements. One PPI member also read and commented on lay summary of report | Multiple time points through research process: inception, design, and results dissemination | Unable to assess |

| Sanger et al 41 | The research team included a patient who experienced a postoperative infection—no further details provided | Not reported | Not reported | Consult |

| Sanger et al 42 | The research team included 1 patient advisor who previously experienced a postdischarge SSI. A second group of 6 patient advocates |

The patient adviser was involved in “all aspects,” including study design, data analysis, technology development, and manuscript preparation. The patient advisor represented the patients' perspective at weekly team meetings A second group of 6 patients were interviewed as part of the design refinement. This group of patients were patient advocates who had previously volunteered to advise the hospital on matters affecting patients |

Multiple time points through research process; design, analysis, and results dissemination | Collaborate |

| Wiseman et al 43 | A community‐based research advisory focus group |

A preliminary draft of the survey was developed and informed by a community‐based research advisory focus group: CARDS. CARDS are trained patient advisors who advise researchers and reflect the views of racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic groups seldom represented in research planning and activities. The CARDS input and feedback provided a “patient's perspective” that informed survey development |

Single time point during the preliminary drafting of the survey | Consult |

Abbreviations: CARDS: Community Advisors on Research Design and Strategy; HCW, health care workers.

TABLE 3.

Compliance of studies with the GRIPP2 checklist 6

| Reference | PPI aims | PPI methods | PPI results | PPI discussion and conclusion | PPI reflections and critical perspective |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anderson et al 36 | ✓✓ | ||||

| Lee et al 37 | ✓✓ | ✓ | |||

| McCaughan et al 38 | ✓✓ | ✓✓ | ✓✓ | ✓✓ | |

| McNair et al 39 | ✓ | ✓✓ | ✓✓ | ||

| Reeves et al 40 | ✓✓ | ✓✓ | ✓✓ | ✓✓ | ✓✓ |

| Sanger et al 41 | ✓ | ||||

| Sanger et al 42 | ✓✓ | ✓✓ | ✓✓ | ||

| Wiseman et al 43 | ✓✓ | ✓✓ |

Abbreviations: GRIPP2, Guidance for Reporting Involvement of Patients and the Public; PPI, patient and public involvement.

Note: ✓ partial compliance; ✓✓ full compliance.

TABLE 4.

Compliance of studies with Wright and Foster's Critical Appraisal Criteria 33

| Reference | Is the rationale for including users clearly demonstrated? | Is the level of user involvement appropriate? | Is the recruitment strategy appropriate? | Is the nature of training appropriate? | Ethical considerations of managing user involvement? | Methodological considerations of managing user involvement? | Have there been any attempts to involve users in the dissemination? | Has the added value of user involvement been clearly demonstrated? | Evaluation of the user involvement component of the research? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anderson et al 36 | ✓ | ||||||||

| Lee et al 37 | ✓✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| McCaughan et al 38 | ✓✓ | ✓✓ | ✓✓ | ✓ | ✓✓ | ||||

| McNair et al 39 | ✓ | ✓✓ | ✓✓ | ✓ | ✓✓ | ✓ | ✓✓ | ||

| Reeves et al 40 | ✓✓ | ✓✓ | ✓✓ | ✓ | ✓✓ | ✓✓ | ✓✓ | ||

| Sanger et al 41 | ✓ | ||||||||

| Sanger et al 42 | ✓✓ | ✓✓ | ✓✓ | ✓✓ | ✓ | ✓✓ | |||

| Wiseman et al 43 | ✓✓ | ✓✓ | ✓✓ |

Note: ✓ Partial compliance; ✓✓ Full compliance.

3.3. Thematic analysis

Three themes were generated from the data: involvement in modifying and refining research processes; connecting and balancing expert and patient views; and sharing personal insights.

3.3.1. Involvement in modifying and refining research processes

Patient involvement was recognised as an important part of refining and modifying discrete elements within the research process, such as patient information leaflets, 40 protocol development, 40 designing and piloting questionnaires, 36 , 39 , 43 developing topic guides for interviews, 38 and manuscript preparation. 38 , 42 In three studies, patients made wider contributions across multiple phases of three studies. 38 , 40 , 42 The authors reported a “collaborative” approach in the four studies involving patients at multiple time points, 38 , 39 , 40 , 42 suggesting embedded involvement beyond discrete one‐step modification and refinement processes, although descriptions were scant.

3.3.2. Connecting and balancing expert and patient views

Balancing differences in expert and patient views was considered important in two studies 37 , 42 and recognised as a challenge in one other. 42 Tensions between different patients and providers, including patient advisors, were identified, 42 leading to conflict that was reported to impede the research. These authors recommended that iterative engagement with ongoing patient input should be adopted. 42 This suggests not only a degree of underlying and unresolved conflict but also implies an attempt to authentically engage with patient advisors as decision makers, beyond simple feedback loops and information giving.

3.3.3. Sharing personal insight

Patients were valued as advisors and regarded as an expert source of information. They were reported to have a “unique perspective” 38 and insights through various personal experiences. 37 , 38 , 41 , 42 , 43 In one study, 38 three patient advisors were positioned as “key informants” with involvement at multiple time points. Their contributions and insights were considered crucial to the research. 38 Although two of the eight studies briefly referred to the characteristics of patients, 42 , 43 a range of ethnic, racial, and socioeconomic groups were recruited to the research team in one study. 43 Overall, it was evident that patients shared their personal insights and that these insights influenced the research endeavour.

4. DISCUSSION

Research shows patient involvement has benefits for the both the health system and the community, 44 but to the best of our knowledge, this is the first review to examine the involvement of patients in the conduct of surgical wound care research. The eight studies involved patients in a variety of ways but not comprehensively throughout the planning, conducting, and disseminating processes. There was limited geographical and temporal diversity in the studies identified in our review, which were undertaken in the United States and the United Kingdom and published between 2013 and 2019. In their reviews, both Fergussen et al 16 and Jones et al 5 also found relatively few studies reporting on patient involvement in research. This contrasts markedly with the findings of a recent survey of surgical trial staff and patient stakeholders in UK surgical trials that found over 90% of surveyed trials reported their research being carried out either with or by patients. 45 This may suggest inconsistent development in patient involvement across and between geographical locations, or a potential lag or disconnection between the international rhetoric and the views and expectations of those involved in surgical wound research in the United Kingdom and the United States.

This review found variability in the extent to which patients have been involved in surgical wound care research; however, there are suggestions for how this might occur. For example, Kauffman et al 19 provide 10 recommendations for meaningful engagement of patients in patient‐centred outcome research, such as bringing the research to the communities where patients live, using a period of pre‐engagement to recruit patients to the research team and providing a lay summary of findings at an end‐of‐study celebration. Three additional broader approaches that may assist researchers to enhance patient involvement in surgical wound research are as follows: using a framework and/or toolkit to inform patient participation; undertaking targeted training on the roles that patients may play as coresearchers; and monitoring this participation.

Using a framework to inform the patient's role on the research team is one approach to promoting active involvement. The International Association for Public Participation 46 is one such framework, but there are a huge array of other frameworks that can be used. 10 Various organisations have also developed comprehensive resources and toolkits to promote patient participation 2 , 4 , 13 and other freely available resources. The use of these resources may help guide researchers in developing their competence in engaging with consumers.

Once the extent of this participation has been determined, a second approach is to train patients and researchers about the functional and interactional components of patients' roles in the research project. 47 Functional aspects could reflect the extent of expected participation (ie, where on the spectrum the desired participation sits). The interaction component acknowledges the social interactions, relationships, and contextual demands. Clear documentation of the functional expectations and consideration of the interactional aspects of the role can then be used to develop training for both patients and the wider research team. Educating patients about the functional aspects of their role, and training the research team in shared decision‐making and good communication techniques, may promote more effective patient involvement in the research process. 48

Monitoring patient involvement throughout the research process is a third approach to assist researchers to incorporate patients into health research. Tools such as the patient engagement quality guidance tool 49 can be used to promote authentic patient participation. This tool provides a tangible process to outline the project plan and the expectations for both the patients and academic researchers. Other tools like critical appraisal criteria, 33 which we used in this scoping review, can also help researchers recognise and prioritise patient input, promoting authentic patient participation.

The quality of reporting on patient involvement in included studies was suboptimal. Several other reviewers noted reporting issues. 5 , 6 , 16 , 21 , 50 It is difficult to determine if this relates to the country the study was conducted with the US studies generally appearing to have poorer reporting than the UK ones, or if this is related to the years the papers were published, because excluding Lee 37 the less well reported papers were older. We were also unable to determine if suboptimal reporting was linked to low levels of patient involvement, a lack of awareness about the importance of documenting involvement, or other potential reasons. A notable gap in the quality of reporting was related to recruitment and training, and attempts to involve those with a wide cross‐section of interests in terms of ethnic background, gender, and age, Approaches to patient involvement have been criticised for “exclusivity, tokenism, and a lack of diversity,” with a tendency to select “well‐behaved” white middle class patients who are deemed “appropriate” and “acquiescent.” 7 , 15 This is also a challenge for surgical wound care researchers, particularly being able to identify representative and diverse patients and patients including “hard to reach” minority groups. 19

5. LIMITATIONS

There were several limitations to this review. First, the small number of studies identified may have limited our interpretations and thematic synthesis. Second, although broad search terms were used, we may still have missed articles because of variations in terminology. Third, articles were limited to those in English, so we may have missed potentially important contributions in other languages. A final limitation was that the papers did not provide detailed data on how patient involvement was enacted. Thus, while we used a rigorous process in our review, our findings reflect only what has been reported in the primary research.

6. CONCLUSION

Patient involvement in surgical wound care research appears to be limited, and the reporting of involvement is suboptimal. This scarcity of reporting may indicate the considerable challenges of involving patients in research, particularly those found in wound care research. In addition, the system disconnect in hospitals may also act as a barrier to meaningful patient involvement in research projects. The findings from this study suggest that when patients are involved in surgical wound care research, their contributions and insights are considered an important aspect of shaping, refining, and modifying elements of the research process. This is despite concern about balancing differences in expert and patient views and possible tensions. As suggested earlier, the use of frameworks and guidelines for effective involvement practices can lead to more effective engagement practices. Researchers can also draw on the wider body of literature on patient involvement in health care to help direct them in their future endeavours. 12 However, developing meaningful patient–researcher relationships is pivotal to achieving long‐term sustainable patient involvement. The strategies suggested to include patients in surgical wound care research can be tailored to various research contexts. Additionally, research is required to develop methods and processes to assist both researchers and patients on their involvement in surgical wound care research.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no potential conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

W.C. conceived of this study. All authors except J.P. contributed to writing the protocol. All except B.G. and H.T. were involved in data extraction. All authors were involved in data analysis, interpretation, and writing the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was funded by a Griffith University Health Group Dean's Seed Grant.

APPENDIX A.

TABLE A1.

Search terms

| Consumer | Involvement | Surgical wound |

|---|---|---|

|

patient* consumer* lay OR communi* famil* OR carer* citizen* OR relative* representative* stakeholder* “advisory group” OR “advisory board” public OR user* client* OR knowledge‐user* |

engagement OR involve* view* OR centred centred OR participat* input OR design* collaborative OR partnership consult* OR “lay control” lay‐controlled OR co‐design co‐operative OR co‐creation co‐production preference |

surg* OR postop* post‐op* OR periop* peri‐oper* OR operat* wound* OR infect* site* OR incis* OR dehisc* Primary intention OR secondary intention |

TABLE A2.

Ovid MEDLINE search

| 1 | ((patient* or consumer* or lay or communi* or famil* or carer* or citizen* or relative* or representative* or stakeholder* or advisory group or advisory board or public or user* or client* or knowledge‐user*) adj5 (engagement or preference* or involve* or view* or centered or centred or participat* or input or design* or collaborative or partnership or consult* or lay control or lay‐controlled or co‐design or co‐operative or co‐creation or co‐production)).mp |

| 2 | Patient participation/ |

| 3 | Community participation/ |

| 4 | Stakeholder participation/ |

| 5 | 2 or 3 or 4 |

| 6 | 1 or 5 |

| 7 | ((surg* or postop* or post‐op* or periop* or peri‐oper* or operat*) adj3 (wound* or infect* or site* or incis* or dehisc*)).mp |

| 8 | (primary intention or secondary intention).mp |

| 9 | 7 or 8 |

| 10 | Surgical wound/or surgical wound infection/ |

| 11 | Surgical wound dehiscence/ |

| 12 | 10 or 11 |

| 13 | 9 or 12 |

| 14 | 6 and 13 |

| 15 | Limit 14 to case reports |

| 16 | 14 not 15 |

| 17 | Limit 16 to year = “2004‐Current” |

| 18 | Limit 17 to English language |

TABLE A3.

Detailed information on compliance of studies with the GRIPP2 checklist 6

| Reference | 1. Aim: report the aim of PPI in the study | 2. Methods: provide a clear description of the methods used for PPI in the study | 3. Study results: outcomes—report the results of PPI in the study including both positive and negative outcomes | 4. Discussion and conclusions—outcomes on the extent to which PPI influenced the study overall. Describe positive and negative effects | 5. Reflections/critical perspectives comment critically on the study, reflecting on things that went well and those that did not, so others can learn from this experience |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anderson et al 36 | Preliminary drafts of the questionnaire were refined with input from a sample of 8 patients. | ||||

| Lee et al 37 | Included in key informant interviews on experiences and perspectives of using PGHD in the postoperative SSI setting, which was included in the final data synthesis | Highlights importance of having a broad stakeholder group involved in design process, although does not provide examples specific to consumer involvement | |||

| McCaughan et al 38 | Three patient advisors to act as key informants throughout study | Design and piloting of interview guide and feedback on study findings and early drafts | Involvement in research process was a key strength, which helped to shape interview methodology and interpretation | Contributions were crucial to reflection on the meaning of the interview data and its interpretation | |

| McNair et al 39 | To define a COS for use in trials and other studies, agreed upon by patients | Patient representative involved grouping patient‐related outcomes into different domains. Patients and carers involved in consensus meetings to vote on final list of the COS | As a result of the consensus meeting, patients identified domains, which had overlapping content or themes and voted for them to be combined to prevent confusion | ||

| Reeves et al 40 | To work with a PPI group to inform the conduct and design of a future RCT | Patient representative on steering committee. Two PPI meetings to discuss RCT design elements and how to best engage with future participants | PPI involvement influenced the design of a patient information leaflet to be more user‐friendly, the design and delivery of a wound‐experience questionnaire, strategies for improving adherence to trial allocation in future RCT and ways to incorporate PGHD including digital photos of wounds | PPI meetings changed RCT protocol and design elements including considerations for adherence, reducing participant dropout, and completion time for questionnaires | To ensure clarity about the role of PPI work, to make the best use of PPI panel members' and researchers' time |

| Sanger et al 41 | Including patient as part of multidisciplinary team was a core strength of the study, although did not report what specifically they contributed | ||||

| Sanger et al 42 | To represent the patients' perspective contributing to the development of a paint‐centred data collection tool (mPOWER) |

Patient advisor and patient advocates involved in study design, data analysis, technology development, and manuscript preparation. “Think‐aloud” approach utilised |

Agreement and conflict between patient advisors/advocates and providers impeded design and adoption of mobile technology interface | Highlights importance of an iterative design process, to ensure ongoing input and preventing overshadowing of ideas. Acknowledgement of potential self‐selection bias with recruitment of patient advisors from a pre‐existing panel | |

| Wiseman et al 43 | A community‐based research advisory focus group was used to provide feedback and a patient's perspective | To develop and inform a preliminary survey draft to assess smartphone capability in outpatient wound assessment |

Abbreviations: COS, core outcome set; GRIPP2, Guidance for Reporting Involvement of Patients and the Public; PGHD, patient‐generated health data; PPI, patient and public involvement; RCT, randomised control trial; SSI, surgical site infection.

TABLE A4.

Detailed compliance of studies with Wright and Foster's Critical Appraisal Criteria 33

| Reference | Rationale for including users shown | Appropriate level of user involvement | Appropriate recruitment strategy | Appropriate training | Ethical considerations of user involvement | Methodological considerations of user involvement | Users involved in dissemination | Added user value shown | Evaluation of the user involvement component of the research |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anderson et al 36 | A sample of 8 patients provided feedback on a preliminary questionnaire draft | ||||||||

| Lee et al 37 | Patients were consulted in a second round of interviews after feedback from stakeholder groups to discuss their experience with and perspectives on PGHD use in postoperative SSI detection | Patients who had experience using PGHD for postoperative monitoring | Helped to form the beginnings of a “community of practice” comprising diverse stakeholder perspectives to inform future research on this important topic | ||||||

| McCaughan et al 38 (United Kingdom) | Patient advisors included as key informants throughout study | Collaboration with three patient advisors involving design and piloting of topic guide, data analyses, interpretation of study findings, and comments on early drafts | Patient advisors selected with personal experience with an open surgical wound due to their unique perspective on a niche area | Advisors commented and provided feedback on early drafts of the manuscript | Patient involvement at all key stages of the research process was an important strength and crucial to reflection on the meaning of the interview data and its interpretation | ||||

| McNair et al 39 | Lists patients as essential stakeholders | A patient representative was consulted to help group patient‐reported outcomes into domains. Patients were consulted to pilot a survey draft and vote on the final core outcome set. The patient advocate coauthor collaborated throughout research process including contributing to manuscript writing and agreeing with manuscript overall results and conclusion | Attendees to the consensus meeting had previously been recruited to complete a questionnaire, where non‐probabilistic sampling was used to ensure geographical and caseload variation. The co‐author credentials included being a member of various patient advocate groups | Patient advocate co‐author received travel reimbursement | With concerns that patients may not fully comprehend the clinical terminology used, the “unsure” category was added to the patient consensus meetings so that the terminology could be explained in more detail | The patient advocate coauthor involved in manuscript writing and agreed with overall results and conclusions | Differences between patient and provider consensus meetings lead to changes in the final core outcome set, with domains considered by patients to have overlapping content or themes combined | ||

| Reeves et al 40 | PPI group to inform the conduct and design of a future main trial | Consultation via PPI meetings to discuss RCT design and protocol elements. One PPI member also read and commented on lay summary of report. One patient representative collaborated throughout study as part of the steering committee | Participants had previously been recruited for semi‐structured interviews, where sampling became increasingly purposeful to achieve maximum variation according to age, sex, and type of surgery. Patients recruited were undergoing elective or unplanned (emergency) abdominal operations, including caesarean section, with a primary closed surgical wound | In the PPI meeting, a brief overview of the purpose of a patient information leaflet was presented including structure and type of information reported | PPI group member commented and gave feedback on the plain English summary. Findings from Bluebelle study have been presented at conferences including outside conventional academic circles or generic audiences | PPI meetings influenced study design including questionnaire and PIL refinement and strategies for future participant retention, including increasing the font size of the PIL, making the instructions for completing the Wound Experience Questionnaire more prominent and providing more flexibility around the timing of questionnaire completion | Recommend that there is clarity about the role of PPI work,to make best use of PPI panel members' and researchers' time. Written feedback on the PPI meeting was rated as excellent (4/7 response) or very good (3/7 responses). Comments from members included that PPI was regarded as very important and that it had been valuable to meetothers and share experiences | ||

| Sanger et al 41 | Highlights that including diverse perspectives from a multidisciplinary team including a patient with previous SSI experience a core strength of study | ||||||||

| Sanger et al 42 | Patient advisor and patient advocates as part of a iterative process for developing an app to track symptoms of infections after surgery | Collaboration with patient advisor involved in study design, data analysis, technology development, and manuscript development; consultation with patient advocates on design refinement, coding, and design recommendations | Patient advisors who had previous personal experience with a postoperative SSI were recruited via email using convenience sampling from a pre‐existing database | Recruitment from established advocate database could introduce self‐selection bias, although the value of having expert panel outweighs any potential bias introduced | Patient advisor was involved in manuscript preparation | Highlights the importance of bringing patients into the design process iteratively and directly on the research team. Key discussions related to agreements and conflicts between providers and patients led to significant implications for app design | |||

| Wiseman et al 43 United States | The use of a community‐based research advisory focus group (CARDS) to gain patient's perspectives and help develop and inform a preliminary draft of a survey | Consulted with research advisory focus group to gain patient perspective, which informed and developed preliminary draft of survey to assess smartphone capability in outpatient wound assessment | CARDS are a trained focus group that advise researchers and represent the views of racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic groups that are rarely represented in research |

Abbreviations: PGHD, patient‐generated health data; PIL, patient information leaflet; PPI, patient and public involvement; RCT, randomised control trial; SSI, surgical site infection.

TABLE A5.

Patient involvement in this wound care scoping review (GRIPP2)

| Section and topic | Item |

|---|---|

|

1: Aim: Report the aim of the study |

To develop and conduct a scoping review on patient involvement in surgical wound care, with the aim of reporting the quality, transparency, and consistency in wound care research To involve patients as research partners at key stages in the development and conduct of the scoping review |

|

2: Methods: Provide a clear description of the methods used for PPI in the study |

One consumer advisor (a term widely used for patient/public advisor in Australia) was initially invited to join the research team to provide oversight and input to all stages of the scoping review. Our consumer advisor was involved in: reviewing the initial grant application for the study, reviewing the draft protocol, setting aims, refining research questions, reviewing the draft publication, and decision making in dissemination. The consumer advisor also assisted with analysis of initial themes and checked comprehension of the draft publication. Our consumer advisor also contributed to edits of this article and is a coauthor. |

|

3: Results: Outcomes; report the results of PPI in the study including both positive and negative outcomes |

Patient involvement contributed to the study in several ways, including: • Interpreting results • The consumer advisor checked the comprehension of this article prior to publication and provided feedback and comments from their experiences, which contributed to the write‐up of this article |

|

4: Discussion: Outcomes; comment on the extent to which PPI influenced the study overall. Describe positive and negative effects |

Patient involvement in this study contributed to a more nuanced understanding of the ways in which patients can contribute to a review study of this type, and provided important guidance in both confirming particular decisions, such as research questions, and raising questions based on their experiences and knowledge. The consumer advisor had received previous training in consumer involvement and was actively involved in leading a consumer advisory group attached to the Gold Coast University Hospital, Queensland. There was a pre‐existing relationship between the consumer advisor and academics in the study from previous research, which meant that a level of trust and understanding had already been established from having previously worked together and a mutual appreciation of each other's roles However, there were limitations. The short timeline for completion of the study served to limit potential input from the consumer advisor, and a core team of three researchers (RM, JP, and WC) worked on the literature searches, extraction and initial analysis, and drafting of the paper |

|

5: Reflections: Critical perspective; comment critically on the study, reflecting on the things that went well and those that did not, so others can learn from this experience |

Patient involvement was an important part of this study, as it focused explicitly on the quality and transparency of patient involvement in surgical wound care research. The key challenge was ensuring that our consumer advisor was involved in a way that was meaningful—for both the researchers and consumer advisor. The pre‐existing relationships between the researchers and consumer meant that there was already a level of understanding and trust, which meant that short turnaround times and expectations were negotiated easily. Without pre‐existing relationships, the time limitations might have posed difficulties for some consumer advisors and may have limited the extent to which consumer advisors could be involved. A single consumer was involved in the study, which meant limitations in terms of a diversity of views relating to gender, socioeconomic, cultural, and ethnic backgrounds within the study, which requires further consideration in the future |

Abbreviations: GRIPP2, Guidance for Reporting Involvement of Patients and the Public; PPI, patient and public involvement.

Muir R, Carlini JJ, Harbeck EL, et al. Patient involvement in surgical wound care research: A scoping review. Int Wound J. 2020;17:1462–1482. 10.1111/iwj.13395

REFERENCES

- 1. National Health Medical Research Council (NHMRC) . A Model Framework for Consumer and Community Participation in Health and Medical Research. Canberra, Australia: Commonwealth of Australia; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Canadian Institutes of Health Research Strategy for Patient‐Oriented Research—Patient Engagement Framework—CIHR 2014. http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/48413.html. Accessed March 20, 2020.

- 3. Department of Health . Patient and Public Involvement in the New NHS. London, UK: Department of Health; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Consumers Health Forum . Shifting Gears—Consumers Transforming Health. A White Paper. Canberra: CHF; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jones EL, Williams‐Yesson BA, Hackett RC, Staniszewska SH, Evans D, Francis NK. Quality of reporting on patient and public involvement within surgical research: a systematic review. Ann Surg. 2015;261(2):243‐250. 10.1097/sla.0000000000000768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Staniszewska S, Brett J, Simera I, et al. GRIPP2 reporting checklists: tools to improve reporting of patient and public involvement in research. BMJ. 2017;358:j3453. 10.1136/bmj.j3453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ocloo J, Matthews R. From tokenism to empowerment: progressing patient and public involvement in healthcare improvement. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(8):626‐632. 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cochrane . An International Network for Public Involvement and Engagement in Health and Social Care Research 2018. https://www.cochrane.org/news/international-network-public-involvement-and-engagement-health-and-social-care-research.

- 9. INVOLVE . What Is Public Involvement in Research?. INVOLVE: Eastleigh; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Greenhalgh T, Hinton L, Finlay T, et al. Frameworks for supporting patient and public involvement in research: systematic review and co‐design pilot. Health Expect. 2019;22(4):785‐801. 10.1111/hex.12888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Forsythe L, Heckert A, Margolis MK, Schrandt S, Frank L. Methods and impact of engagement in research, from theory to practice and back again: early findings from the Patient‐Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Qual Life Res. 2018;27(1):17‐31. 10.1007/s11136-017-1581-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sarrami‐Foroushani P, Travaglia J, Debono D, Braithwaite J. Implementing strategies in consumer and community engagement in health care: results of a large‐scale, scoping meta‐review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:402. 10.1186/1472-6963-14-402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. National Health Medical Research Council (NHMRC) . Toolkit for Consumer and Community Involvement in Health and Medical Research. Canberra, Australia: NHMRC; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Manafò E, Petermann L, Vandall‐Walker V, Mason‐Lai P. Patient and public engagement in priority setting: a systematic rapid review of the literature. PLOS One. 2018;13(3):e0193579. 10.1371/journal.pone.0193579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Domecq JP, Prutsky G, Elraiyah T, et al. Patient engagement in research: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):89. 10.1186/1472-6963-14-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fergusson D, Monfaredi Z, Pussegoda K, et al. The prevalence of patient engagement in published trials: a systematic review. Res Involv Engagem. 2018;4:17. 10.1186/s40900-018-0099-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ioannidis JPA, Greenland S, Hlatky MA, et al. Increasing value and reducing waste in research design, conduct, and analysis. Lancet. 2014;383(9912):166‐175. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62227-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Patient‐Centred Outcomes Research Insitute (PCORI) . PCORI Engagement Rubric 2014. https://www.pcori.org/sites/default/files/Engagement-Rubric.pdf. Accessed October 12, 2015.

- 19. Kauffman KS, Dosreis S, Ross M, Barnet B, Onukwugha E, Mullins CD. Engaging hard‐to‐reach patients in patient‐centered outcomes research. J Comp Eff Res. 2013;2(3):313. 10.2117/CER.13.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cacchione PZ. The evolving methodology of scoping reviews. Clin Nurs Res. 2016;25(2):115‐119. 10.1177/1054773816637493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brett J, Staniszewska S, Mockford C, et al. Mapping the impact of patient and public involvement on health and social care research: a systematic review. Health Expect. 2014;17(5):637‐650. 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2012.00795.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Meara JG, Hagander L, Leather AJ. Surgery and global health: a lancet commission. Lancet. 2014;383:12‐13. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62345-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. World Health Organization . Global Guidelines for the Prevention of Surgical Site Infection. Geneva: WHO; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19‐32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5(69):1‐9. 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Colquhoun HL, Levac D, O'Brien KK, et al. Scoping reviews: time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(12):1291‐1294. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA‐ScR): checklist and explanation the PRISMA‐ScR statement. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467‐473. 10.7326/m18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. National Health Medical Research Council (NHMRC) . Statement on Consumer and Community Involvement in Health and Medical Research. Canberra, Australia: NHMRC; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Greenhalgh T, Peacock R. Effectiveness and efficiency of search methods in systematic reviews of complex evidence: audit of primary sources. BMJ. 2005;331(7524):1064‐1065. 10.1136/bmj.38636.593461.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5:210. 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Oremus M, Oremus C, Hall GBC, McKinnon MC. Inter‐rater and test–retest reliability of quality assessments by novice student raters using the Jadad and Newcastle–Ottawa scales. BMJ Open. 2012;2(4):e001368. 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Amirav I, Vandall‐Walker V, Rasiah J, Saunders L. Patient and researcher engagement in health research: a parent's perspective. Pediatrics. 2017;140(3):e20164127. 10.1542/peds.2016-4127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wright D, Foster C, Amir Z, Elliott J, Wilson R. Critical appraisal guidelines for assessing the quality and impact of user involvement in research. Health Expect. 2010;13(4):359‐368. 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2010.00607.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Vaismoradi M, Turunen H, Bondas T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs Health Sci. 2013;15(3):398‐405. 10.1111/nhs.12048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cornish F, Gillespie A, Zittoun T. Collaborative Analysis of Qualitative Data. London: Sage Publications; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Anderson M, Ottum A, Zerbel S, Sethi A, Gaines ME, Safdar N. A survey to examine patient awareness, knowledge, and perceptions regarding the risks and consequences of surgical site infections. Am J Infect Control. 2013;41(12):1293‐1295. 10.1016/j.ajic.2013.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lee JR, Evans HL, Lober WB, Lavallee DC, Tejedor SC, Dellinger EP. A stakeholder‐driven framework for evaluating surgical site infection surveillance technologies. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2019;20(7):588‐591. 10.1089/sur.2019.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. McCaughan D, Sheard L, Cullum N, Dumville J, Chetter I. Patients' perceptions and experiences of living with a surgical wound healing by secondary intention: a qualitative study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2018;77:29‐38. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. McNair AG, Whistance RN, Forsythe RO, et al. Core outcomes for colorectal cancer surgery: a consensus study. PLoS Med. 2016;13(8):e1002071. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Reeves BC, Rooshenas L, Macefield RC, et al. Three wound‐dressing strategies to reduce surgical site infection after abdominal surgery: the Bluebelle feasibility study and pilot RCT. Health Technol Assess Rep. 2019;23(39):vii‐165. 10.3310/hta23390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sanger PC, Hartzler A, Han SM, et al. Patient perspectives on post‐discharge surgical site infections: towards a patient‐centered mobile health solution. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):e114016. 10.1371/journal.pone.0114016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sanger PC, Hartzler A, Lordon RJ, et al. A patient‐centered system in a provider‐centered world: challenges of incorporating post‐discharge wound data into practice. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016;23(3):514‐525. 10.1093/jamia/ocv183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wiseman JT, Fernandes‐Taylor S, Barnes ML, Tomsejova A, Saunders RS, Kent KC. Conceptualizing smartphone use in outpatient wound assessment: patients' and caregivers' willingness to use technology. J Surg Res. 2015;198(1):245‐251. 10.1016/j.jss.2015.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. McColl‐Kennedy J, Snyder H, Elg M, et al. The changing role of the health care customer: review, synthesis and research agenda. J Serv Manag. 2017;28(1):2‐33. 10.1108/JOSM-01-2016-0018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Crocker JC, Pratt‐Boyden K, Hislop J, et al. Patient and public involvement (PPI) in UK surgical trials: a survey and focus groups with stakeholders to identify practices, views, and experiences. Trials. 2019;20(119):1‐15. 10.1186/s13063-019-3183-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.International association for public participation. Welcome to IAP2 Australasia Australasia: IAP2; 2019 [Available from: https://www.iap2.org.au/.

- 47. Rowland P, Brosseau M, Houle C. Patient roles in engagement‐capable environments: multiple perspectives. Healthc Q. 2018;21:45‐49. 10.12927/hcq.2018.25639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Snyder H, Engström J. The antecedents, forms and consequences of patient involvement: a narrative review of the literature. Int J Nurs Stud. 2016;53:351‐378. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Patient Focused Medicines Development . Patient Engagement Quality Guidance Tool. Synergist: Bruxelles, Belgium; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Brett J, Staniszewska S, Simera I, et al. Reaching consensus on reporting patient and public involvement (PPI) in research: methods and lessons learned from the development of reporting guidelines. BMJ Open. 2017;7(10):e016948. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]