Abstract

Surgical site infection (SSI) is associated with increased morbidity, length of stay, and cost. Cyanoacrylate glue is a low‐cost, fluid‐proof, antimicrobial barrier. The aim of this systematic review is to assess the use of cyanoacrylate glue after standard wound closure versus dressings in the reduction of SSI. Medline, Embase, Cochrane Library, and clinical trial registries were searched with no restrictions in accordance with PRISMA guidelines. Eligibility criteria were prospective studies comparing glue versus dressings after standardised wound closure. Two reviewers independently screened articles and utilised GRADE for quality assessment. Meta‐analysis was not performed because of the heterogeneity of the data. Three articles were included in the review. Study quality was uniformly low. Incidence of SSI was low, between 0% and 4%. No significant differences were reported in the single randomised controlled trial. A single non‐randomised parallel group trial reported a significant reduction in the incidence of SSI in the cyanoacrylate group. There was no consistent evidence demonstrating reduction in SSI as a result of the use of cyanoacrylate glue. Future studies should assess the use of cyanoacrylate in procedures with a higher rate of SSI, for example, lower limb bypass.

Keywords: adhesive, cyanoacrylate, surgical site infection

1. BACKGROUND

The Centre for Disease Control and Prevention defines surgical site infection (SSI) as a postoperative infection occurring within 30 days (superficial infection) or 90 days (deep infection). Superficial infection involves only the skin and subcutaneous fat, whereas deep involves fascia and muscle.1, 2

SSI increases morbidity, mortality, length of stay, and costs after surgery.3, 4 In the United Kingdom, between 2015 and 2016, the incidence of SSI was reported to be as high as 10% for inpatient surgical procedures.5 In the United States, the average cost for one patient who suffers an SSI is $20 842.3 Furthermore, it is estimated that the additional cost of an SSI for a patient undergoing a surgical procedure in the United Kingdom ranged from £243 to £20 356,6 with no extra increase in reimbursement, especially for readmissions to hospital. The result is that significant SSI rates render surgery unprofitable to hospital trusts in the United Kingdom. Interventions to reduce SSIs thus hold great potential.

Cyanoacrylate glue encompasses a range of tissue adhesives in current clinical use in the form of octyl‐cyanoacrylate or butyl‐cyanoacrylate. These tissue adhesives are sold under a number of brand names, such as Dermabond (Ethicon, Somerville, NJ) or Glubran (GEM, Viareggio, Italy). Cyanoacrylate glue has an array of clinical applications from closure of lacerations in children to fixation of mesh in hernia repair.7, 8

The application of cyanoacrylate glue after wound closure is defined as a complex dressing9 with several advantages: a waterproof barrier for up to 10 days, a transparent dressing that is easy to inspect, and reduced nursing time for dressing changes.10 Conversely, it has been suggested that traditional dressings can become fluid soaked, require replacement, and need to be removed for wound review. Furthermore, there is some pre‐clinical evidence to suggest that cyanoacrylate glue has antimicrobial properties against Gram‐positive bacteria, 11, 12 which are common pathogens in SSIs.

Cyanoacrylate glue is relatively inexpensive, with unit costs varying from $6.57 to $26.28. It is therefore a comparable expense in comparison with repeated dressing changes.13

The aim of this systematic review was to assess the effectiveness of cyanoacrylate glue in comparison with dressings following standard wound closure for prevention of SSIs. The primary outcome to be assessed was reduction of SSIs.

2. METHODS

This systematic review was undertaken in concordance with the PRISMA guidelines.

2.1. Search strategy

MEDLINE, Embase, and the Cochrane Library were searched on 11th September 2017 and updated on 4th April 2018. The following clinical trial registries were also searched: www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu, www.isrctn.com, www.clinicaltrials.gov, and http://www.who.int/ictrp/en using identical keywords.

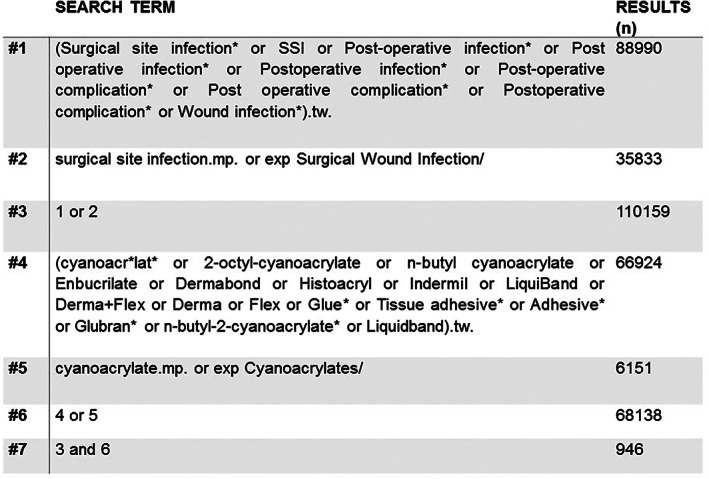

Search terms consisted of the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and exploded Subject Headings for “cyanoacrylate” and “surgical site infection” in addition to keywords (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Search of MEDLINE database performed using Ovid on 11 September 2017

Searches of Embase (Embase Classic+Embase 1947 to 11 September 2017) and MEDLINE (Ovid MEDLINE[R] ALL 1946 to 11 September 2017) were performed using the online platform Ovid based on “Title” and “Abstract,” with no restrictions imposed. Searches of the Cochrane Library utilised the Cochrane Wiley (John Wiley & Sons) online platform and were performed on “Title” and “Abstract,” and review articles were not included as per the inclusion criteria. References of relevant Cochrane reviews were reviewed for eligible articles.

References of all included articles were also examined for eligible articles.

2.2. Eligibility criteria

Two reviewers (MM, CL) independently screened retrieved articles against the inclusion criteria. Discrepancies between the two reviewers were independently resolved by a third reviewer (AC).

Included articles had the following characteristics:

-

1

Prospective randomised or parallel‐group study

-

2

Intervention arm contained patients treated with cyanoacrylate glue following standard wound closure (eg, suture, staples) after a surgical procedure

-

3

Control arm included patients treated with a standard dressing and an identical technique of wound closure

Exclusion criteria were:

-

4

Cyanoacrylate was used instead of standard skin closure with sutures or staples

-

5

Study assessed preoperative application of cyanoacrylate glue

-

6

Review article or letter

-

7

Animal and in vivo studies

No restrictions regarding publication date, publication language, or publication type (eg, conference abstract) were imposed.

2.3. Data extraction and quality assessment

Data were extracted by two reviewers (MM, AT) and imported using Microsoft Excel (Richmond, Virginia). Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) was performed by two reviewers (MM, AT), and the GRADE platform was used to produce a Summary of Findings table (see Supporting Information). Two reviewers (MM, AT) performed a risk‐of‐bias assessment for all included articles using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool (see Supporting Information).

2.4. Meta‐analysis

Data was not pooled for meta‐analysis because of important heterogeneity between studies (see Section 3).

2.5. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed on the reported raw data for articles not reporting P‐values. Fisher's exact test (two‐tailed) was performed using Prism v7 (GraphPad Software). A P‐value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Literature search

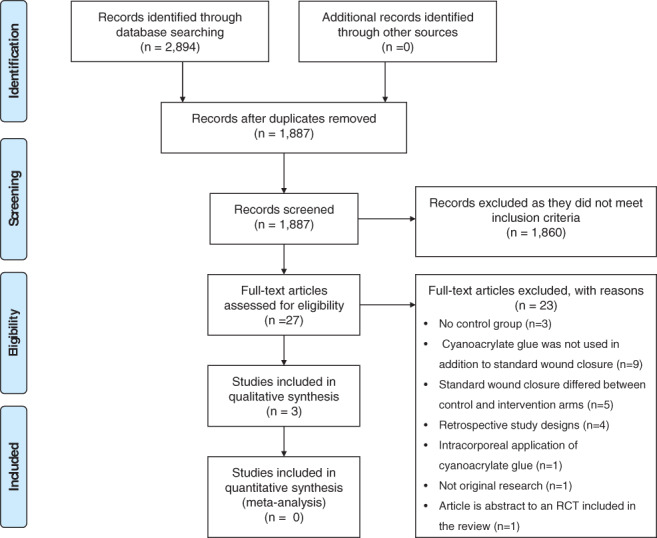

Searches of MEDLINE, Embase, and the Cochrane Library returned 2894 articles (see PRISMA diagram, Figure 2). After removing duplicates, 1887 articles were screened on title and abstract against the inclusion criteria. Full‐text review was performed on 27 articles; 3 articles were included in the systematic review.

Figure 2.

PRISMA flowchart illustrating article inclusion

3.2. Excluded studies

Studies were excluded after full‐text review for the following reasons: no control group (n = 3); cyanoacrylate glue was not used in addition to standard wound closure (n = 9); standard wound closure differed across control and interventions arms (n = 5); retrospective study designs (n = 4); duplicate publication (n = 1); intra‐corporeal application of cyanoacrylate glue (n = 1); and article not original research (n = 1).

3.3. Study characteristics

A single randomised controlled trial of hip arthroplasty was included in the review.14 The remaining two articles comprised of non‐randomised, parallel‐group trials in aesthetic surgery15 and paediatric circumcision16 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Study characteristics of the included RCTs

| Year | First author | Study design | Inclusion criteria | Intervention arm | Control arm | Intervention N | Control N | Mean age ‐intervention arm | Mean age ‐control arm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | Siddiqui et al14 | RCT | Patients undergoing primary hip arthroplasty | Subcuticular suture, cyanoacrylate glue and Opsite | Subcuticular suture and Opsite dressing | 67a | 65a | 65 | 66 |

Original study population n=198, Tegaderm™ dressing and cyanoacrylate glue group not included in review analysis as no comparable control group.

Sample size for the RCT was n = 132. Sample size ranged from n = 90 to n = 900, with a combined total of 1122 participants (Table 2).

Table 2.

Study characteristics of the included prospective non‐randomised trials

| Year | First author | Study design | Inclusion criteria | Intervention arm | Control arm | Intervention N | Control N | Mean age intervention arm | Mean age control arm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | Grimaldi et al15 | Prospective non‐randomised | Abdomino‐plasties, breast augmentation/reduction, limb dermolipectomy, scar revision | Subcuticular suture, cyanoacrylate glue and sterile gauze | Subcuticular suture and sterile gauze | 450 | 450 | 37–45a | 37–45b |

| 2009 | Ozturk et al16 | Prospective non‐randomised | Circumcision | Subcuticular suture, cyanoacrylate glue and antibiotic ointment | Subcuticular suture and antibiotic ointment | 190 | 57 | Not stated (range 1‐12 y) | Not stated (range 1‐12 y) |

Range of average ages across control groups, average age in original article given for each operation type.

Range of average ages across intervention groups, average age in original article given for each operation type.

A single article assessed the use of cyanoacrylate glue in clean‐contaminated cases in paediatric circumcision surgery.16 The remaining two articles undertaken in adults examined the use of cyanoacrylate glue in clean cases: total hip replacement14 and cosmetic surgery (abdominoplasties, breast augmentation, dermolipectomy, and scar revision).15

Wound closure with subcuticular sutures and subsequent application of cyanoacrylate glue was used in the intervention arm of all included articles. Siddiqui et al further dressed the wound with Opsite in both arms (United Kingdom).14 Ozturk et al16 compared subcuticular sutures and antibiotic ointment with or without cyanoacrylate glue.

Definitions of SSI varied across articles, with none of the included studies utilising the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention definition. Definitions of SSI for each of the included articles were accepted. Siddiqui et al14 defined SSI as patient‐reported infection requiring a course of antibiotics prescribed by a general practitioner. Grimaldi et al15 defined SSI by the presence of symptoms and positive clinical findings (erythema, pain, and colour of the wound). Ozturk et al16 did not define SSI.

3.4. Heterogeneity

There were several key features of the trials that precluded meta‐analysis.

Clinically, two of the trials examined adults, and one was in paediatrics. Two of the trials examined clean surgery, whilst one examined contaminated surgery.

Methodologically, one of the trials was randomised, one was a prospective parallel‐group study, and one was a sequential (before and after) prospective study. Definitions of SSI also varied between trials.

Finally, statistically, there were only 28 primary endpoints (total SSI incidence 2%).

3.5. Bias within studies

To assess the risk of bias within each study the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool was utilised (Appendix S2). There were no high‐quality RCTs.

3.6. Incidence of SSI

No significant results for the additional application of cyanoacrylate glue on the incidence of SSIs were reported from the RCT (Table 3 and Figure 3). Siddiqui et al14 reported an increase in SSI in the intervention group (SSI = 3) in comparison with the control group (SSI = 1) (P = 0.62).

Table 3.

Reported incidence of surgical site infection (SSI) for intervention and control groups for the included articles

| Year | First author | Study design | Total N | Number of SSI in intervention group | Number of SSI in control group | P‐value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | Siddiqui et al14 | RCT | 132a | 3/67 (4%) | 1/65 (2%) | 0.62b |

| 2015 | Grimaldi et al15 | Prospective non‐randomised | 900 | 6/450 (1%) | 18/450 (4%) | 0.03* |

| 2009 | Ozturk et al16 | Prospective non‐randomised | 247 | 0/190 (0%) | 0/57 (0%) | >0.05 |

Original study population n = 198, Tegaderm dressing and cyanoacrylate glue group not included in review analysis.

Fisher's exact test calculated using reported data.

Figure 3.

Incidence of surgical site infection in control arm and intervention arm of included articles. Total sample size is indicated above each bar

Grimaldi et al15 (n = 900) reported a significant reduction in SSI in the intervention group (SSI n = 6) in comparison with the control group (SSI n = 18) (P = 0.03). Ozturk et al16 reported no SSI across both the intervention and control groups.

4. DISCUSSION

This is the first systematic review solely assessing the use of cyanoacrylate glue in addition to standard wound closure for prevention of postoperative SSI. There was no consistent difference in the incidence of SSI across studies, with a significant SSI reduction found only in one prospective parallel group study in aesthetic surgery. GRADE recommends this as very low‐quality evidence supporting the use of cyanoacrylate glue as a dressing in the prevention of SSI (Appendix S2). Cyanoacrylate glue offers a waterproof barrier for ~10 days, which in theory would avoid contamination of the wound—this has been defined as a complex dressing in preliminary studies.9 This property is of particular importance if the wound is in close proximity to urine, faeces, or stoma contents. The therapeutic effect of cyanoacrylate glue is thought to be because of the barrier effect in addition to pre‐clinical evidence demonstrating antimicrobial properties.11 In clean and clean‐contaminated surgery, providing a physical barrier around the incision is desirable. Cyanoacrylate glue as a barrier would not be indicated in dirty operations when the wound is allowed to drain freely.

Based on the findings reported by Grimaldi et al,15 at most, an absolute risk reduction of 2.7% was achieved with the use of cyanoacrylate glue (number needed to treat of 38). Dermabond® has a unit cost of £19.47. A simple dressing such as Mepore® costs £0.92/unit. The additional cost of treating 38 patients with one tube of Dermabond in comparison with three Mepore dressings (based on three dressing changes as an inpatient) would be £16.71.

However, the average cost of a single case of SSI is estimated to be $20 842.3 Therefore, in the future, if a treatment effect is confirmed, it is likely that is would be at least cost‐neutral and thus translate into practice.

Although wound closure and dressing are important steps in the prevention of SSI, there are additional factors that are also likely to alter the risk of SSI, such as intra‐operative hypothermia and antibiotic prophylaxis.17, 18 In addition, it is possible that complications such as haematoma formation alter the risk of infection. These factors were not considered within the included articles and were outside the scope of this review.

4.1. Comparison with other literature

Incidence of SSI identified in the included articles is similar to those reported in the national statistics with the National Health Service. For orthopaedic procedures, the national incidence in the United Kingdom is <1%. However, Ozturk et al reported not a single case of SSI, which is far lower than would be expected for paediatric circumcision.

In hepatobiliary surgery, Shiba et al19 compared the use of cyanoacrylate glue in addition to subcuticular sutures versus stapled closure (n = 90) in a prospective non‐randomised trial. There was no significant difference in SSI between the groups.

In orthopaedic surgery, Mudd et al20 compared the use of cyanoacrylate glue in addition to subcuticular suture with stapled closure in 105 patients undergoing acetabular repair surgery in a randomised controlled trial and reported both a low incidence of SSI and no significant difference between groups. Miller et al21 compared the use of cyanoacrylate glue in addition to subcuticular suture to closure with staples in a series of 459 knee and hip arthroplasties. No significant difference was reported for the incidence of SSI between groups. Almustafa et al22 assessed the use of sutures and additional cyanoacrylate glue in comparison with sutures, or staples, alone in a retrospective study of 2100 patients undergoing knee arthroplasty. In the additional cyanoacrylate group, 4.6% of patients developed SSI, which was significantly higher (P = 0.003) in comparison with the 1.0% of patients in the suture group and 1.9% of patients in the staples group.

In a retrospective study of 93 patients undergoing hip arthroplasty with no control group, Khurana et al23 reported no cases of SSI with the use of cyanoacrylate glue in addition to standard wound closure. Thus, in elective orthopaedic surgery, currently, there is no evidence for benefit for the use of cyanoacrylate. Whether this is because so few SSIs are reported or that it is ineffective is debatable.

In cardiac surgery, Grauhan et al24 compared the use of cyanoacrylate glue applied after Donati sutures with subcutaneous running sutures alone in a non‐randomised prospective trial including 90 obese patients undergoing midline sternotomy. Grauhan et al24 grouped deep and superficial wound infections together and reported a significant reduction in SSI in the cyanoacrylate glue‐sealed Donati sutures (two superficial infections) compared with the control group using subcuticular sutures alone (seven superficial infections +two deep infections) (P < 0.05). In a large retrospective study of 1360 of patients undergoing cardiac surgery, Souza et al reported a significant reduction (P < 0.001) in the incidence of SSI (superficial and deep) in the intervention group using additional cyanoacrylate glue (2.1%) compared with the control group (4.9%).25

In paediatric surgery, Romero et al assessed the use of subcuticular suture and either cyanoacrylate glue or Steri‐Strips® in the closure of laparoscopic ports after laparoscopic appendectomy.26 A single case of SSI occurred in the Steri‐Strips® group—no significant difference was identified in the incidence of SSI.

4.2. Strengths

This review was undertaken in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines using a predefined protocol to assess prospective studies with a similar method of wound closure before a dressing or cyanoacrylate glue was applied to minimise confounding. Statistical analysis was applied in studies that previously omitted this. Searches were comprehensive and utilised three databases (MEDLINE, Embase, and Cochrane Libraries), with no limits imposed on the search regarding date of publication or language. A comparison with excluded studies was made.

4.3. Limitations

Although articles not published in English were included in this review, the databases searched to identify articles predominantly included articles from Europe and the United States. Data published in articles not available on Medline, Embase, Cochrane, or the RCT registries could have been missed.

Given that the definitions of SSI were accepted despite one article not providing a definition of SSI, this may have reduced the validity of the data included in this review. Additional factors that may affect wound infection, such as incidence of haematoma, were not considered as it was deemed to be outside the scope of this review. These factors are likely to be clinically important.

Important problems encountered included a low rate of SSI, limiting the power of the studies included. Furthermore, none of the included studies utilised the CDC definition of SSI despite it being in use for two decades.

4.4. Future research/implications

Future research should be adequately powered by considering a surgery with a high SSI rate, where the pathogen comes from the epidermis or external bodily fluids and not from a contaminated body cavity, for example, lower limb arterial bypass surgery.

Future studies should also conceal allocation of treatment until the point of wound dressing from the surgical team and should ensure adequate assessor blinding—this would be easily achievable at day 10 when the glue is no longer visible.

A standard definition of SSI should be utilised in future studies, including a time interval of 90 days as per the CDC definition.

5. CONCLUSION

There is no high‐quality evidence to suggest that the rate of SSI is reduced from the use of cyanoacrylate glue as a dressing. Future adequately powered research, including operations with a high SSI rate from skin or body fluid pathogens, such as lower limb arterial bypass, would be beneficial.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Supporting information

Appendix S1. Cochrane risk of bias assessment.

Appendix S2. Summary of finding table for grading of recommendations assessment, development and evaluation.

Machin M, Liu C, Coupland A, Davies AH, Thapar A. Systematic review of the use of cyanoacrylate glue in addition to standard wound closure in the prevention of surgical site infection. Int Wound J. 2019;16:387–393. 10.1111/iwj.13044

REFERENCES

- 1. Horan TC, Gaynes RP, Martone WJ, Jarvis WR, Emori TG. CDC definitions of nosocomial surgical site infections, 1992: a modification of CDC definitions of surgical wound infections. Am J Infect Control. 1992;20(5):271‐274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. National Healthcare Safety Network CfDCaP . Surgical site infection (SSI) event. 2017.

- 3. de Lissovoy G, Fraeman K, Hutchins V, Murphy D, Song D, Vaughn BB. Surgical site infection: incidence and impact on hospital utilization and treatment costs. Am J Infect Control. 2009;37(5):387‐397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Klevens RM, Edwards JR, Richards CL Jr, et al. Estimating health care‐associated infections and deaths in US hospitals, 2002. Public Health Rep. 2007;122(2):160‐166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Public Health England . Surveillance of Surgical Site Infections in NHS Hospitals in England, 2015/16. London, UK: Public Health England; December 2016.

- 6. Badia JM, Casey AL, Petrosillo N, Hudson PM, Mitchell SA, Crosby C. The impact of surgical site infection on healthcare costs and patient outcomes: a systematic review of the economic and quality of life burden associated with surgical site infections in six European countries. J Hosp Infect. 2017;96:1‐15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Quinn J, Drzewiecki A, Li M, et al. A randomized, controlled trial comparing a tissue adhesive with suturing in the repair of pediatric facial lacerations. Ann Emerg Med. 1993;22(7):1130‐1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sanders D, Waydia S. A systematic review of randomised control trials assessing mesh fixation in open inguinal hernia repair. Hernia. 2014;18(2):165‐176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bluebelle Study Group . Bluebelle study (phase a): a mixed‐methods feasibility study to inform an RCT of surgical wound dressing strategies. BMJ Open. 2016;6(9):e012635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Borley N, Mortensen N. Topical adhesive as a wound dressing for elective abdominal surgery. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2001;83(4):285‐286. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Quinn JV, Osmond MH, Yurack JA, Moir PJ. N‐2‐butylcyanoacrylate: risk of bacterial contamination with an appraisal of its antimicrobial effects. J Emerg Med. 1995;13(4):581‐585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Singer AJ, Mohammad M, Tortora G, Thode HC, McClain SA. Octylcyanoacrylate for the treatment of contaminated partial‐thickness burns in swine: a randomized controlled experiment. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7(3):222‐227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Joint Formulary Committee . British National Formulary (Online). London, UK: BMJ Group and Pharmaceutical Press; 2018. [Skin Adhesives]. https://bnf.nice.org.uk/medical-device-type/skin-adhesives-2.html. Accessed April 4, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Siddiqui M, Bidaye A, Baird E, et al. Wound dressing following primary total hip arthroplasty: a prospective randomised controlled trial. J Wound Care. 2016;25(1):40, 42–45. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/o/cochrane/clcentral/articles/441/CN-01168441/frame.html. Accessed April 4, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Grimaldi L, Cuomo R, Brandi C, Botteri G, Nisi G, D'Aniello C. Octyl‐2‐cyanoacrylate adhesive for skin closure: eight years experience. In Vivo. 2015;29(1):145‐148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ozturk H, Karaaslan K, Kocoglu H. Use of glubran 2 surgical glue in circumcision results in a comfortable postoperative period. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2009;18(4):381‐384. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Liu Z, Dumville JC, Norman G, et al. Intraoperative interventions for preventing surgical site infection: an overview of Cochrane reviews. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018;(2). http://cochranelibrary-wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD012653.pub2/abstract. Accessed April 4, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Melling AC, Ali B, Scott EM, Leaper DJ. Effects of preoperative warming on the incidence of wound infection after clean surgery: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2001;358(9285):876‐880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shiba H, Shirai Y, Sakamoto T, et al. Assessment of subcuticular suture for prevention of surgical site infection in hepatobiliary and pancreatic surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;221:e92. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mudd C, Boudreau J, Moed B. A prospective randomized comparison of two skin closure techniques in acetabular fracture surgery. J Orthop Traumatol. 2013;15(3):189‐194. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/o/cochrane/clcentral/articles/645/CN-01040645/frame.html, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4182586/pdf/10195_2013_Article_282.pdf. Accessed April 4, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Miller AG, Swank ML. Dermabond efficacy in total joint arthroplasty wounds. Am J Orthop. 2010;39(10):476‐478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Almustafa MA, Ewen AM, Deakin AH, Picard F, Clarke JV, Mahmood FF. Risk factors for surgical site infection following lower limb arthroplasty: a retrospective cohort analysis of 3932 lower limb arthroplasty procedures in a high volume arthroplasty unit. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33:1861‐1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Khurana A, Parker S, Goel V, Alderman PM. Dermabond wound closure in primary hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop Belg. 2008;74(3):349‐353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Grauhan O, Navasardyan A, Hofmann M, Müller P, Hummel M, Hetzer R. Cyanoacrylate‐sealed Donati suture for wound closure after cardiac surgery in obese patients. Interact Cardiovasc Thor Surg. 2010;11(6):763‐767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Souza E, Fitaroni R, Januzelli D, Macruz HM, Camacho JC, Souza MR. Use of 2‐octyl cyanoacrylate for skin closure of sternal incisions in cardiac surgery: observations of microbial barrier effects. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24(1):151‐155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Romero P, Frongia G, Wingerter S, Holland‐Cunz S. Prospective, randomized, controlled trial comparing a tissue adhesive (DermabondTM) with adhesive strips (Steri‐StripsTM) for the closure of laparoscopic trocar wounds in children. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2011;21(3):159‐162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1. Cochrane risk of bias assessment.

Appendix S2. Summary of finding table for grading of recommendations assessment, development and evaluation.