Abstract

The aim of this study is to evaluate the clinical and economic burden of wound care in the Tropics via a 5‐year institutional population health review. Within our data analysis, wounds are broadly classified into neuro‐ischaemic ulcers (NIUs), venous leg ulcers (VLUs), pressure injuries (PIs), and surgical site infections (SSIs). Between 2013 and 2017, there were a total of 56 583 wound‐related inpatient admissions for 41 461 patients, with a 95.1% increase in wound episodes per 1000 inpatient admissions over this period (142 and 277 wound episodes per 1000 inpatient admissions in 2013 and 2017, respectively). In 2017, the average length of stay for each wound episode was 17.7 days, which was 2.4 times that of an average acute admission at our institution. The average gross charge per wound episode was USD $12 967. Among the 12 218 patients with 16 674 wound episodes in 2017, 71.5% were more than 65 years of age with an average Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) of 7.2. Half (51.9%) were moderately or severely frail, while 41.3% had two or more wound‐related admission episodes. In 2017, within our healthcare cluster, the gross healthcare costs for all inpatient wound episodes stand at USD $216 million within hospital care and USD $596 000 within primary care. Most NIU patients (97.2%) had diabetes and they had the most comorbidities (average CCI 8.4) and were the frailest group of patients (44.9% severely frail). The majority of the VLU disease burden was at the specialist outpatient setting, with the average 1‐year VLU recurrence rate at 52.5% and median time between healing and recurrence at 9.5 months. PI patients were the oldest (86.5% more than 65 years‐old), constituted the largest cohort of patients with 3874 patients at an incidence of 64.6 per 1000 admissions in 2017, and have a 1‐year all‐cause mortality rate of 14.3%. For SSI patients, there was a 125% increase of 14.2 SSI wound episodes per 1000 inpatient admissions in 2013 to 32.0 in 2017, and a 413% increase in wound‐related 30‐day re‐admissions, from 40 in 2013 (4.1% of all surgeries) to 205 (8.3% of all surgeries) in 2017. The estimated gross healthcare cost per patient ranges from USD $15789–17 761 across the wound categories. Similar to global data, there is a significant and rising trend in the clinical and economic burden of wound care in Tropics.

Keywords: chronic wounds, neuro‐ischaemic ulcer, pressure injury, surgical site infection, venous leg ulcer

Key Messages.

between 2013 and 2017, there were a total of 56 583 wound‐related inpatient admissions for 41 461 patients, with a 95.1% increase in wound episodes (142 and 277 wound episodes per 1000 inpatient admissions in 2013 and 2017, respectively)

in 2017, the average length of stay for each wound episode was 17.7 days, which was 2.4 times that of an average acute admission

among the 12 218 patients with 16 674 wound episodes in 2017, 71.5% were more than 65 years of age with an average Charlson Comorbidity Index of 7.2

in 2017, the average gross charge per wound episode was USD $12 967

within our healthcare cluster, the gross healthcare costs for all inpatient wound episodes stand at USD $216 million within hospital care and USD $596 000 within primary care

1. INTRODUCTION

Although there is no consensus for their duration, chronic wounds are generally recognised as wounds that do not heal beyond the amount of time which should be sufficient for healing, often arbitrarily defined as 1 month.1, 2 Wounds present a substantial clinical and economic burden to healthcare systems globally with significant reductions in quality of life for those affected. From a retrospective analysis of 5% of the Medicare dataset, including both acute and chronic wounds, it was estimated that 8.2 million Medicare beneficiaries had at least one type of wound, with financial burden to Medicare ranging from USD $28.1 billion to USD $96.8 billion in the United States (US) in 2014.3 Between 2012 and 2013, Wales was estimated to have a chronic wound prevalence of 6% within primary care, amounting to 5.5% of the National Health Service expenditure.4 In 2012, the cost associated with wound management in United Kingdom (UK) was estimated at £4.5 to £5.1 billion.5

Within the literature, most published data on the burden of wound care are generally from Western societies within temperate regions. In a systematic review on the social and economic burden of chronic wounds, which identified 30 studies, there was no study based on populations within the Tropics, aside from Brazil (three studies) being the closest.6 In another systematic review on the prevalence of chronic wounds in the general population, which identified 17 studies, only one study (from Indonesia) was based on a study population within the Tropics and it was based only on pressure ulcers.7 As such, we aimed to evaluate the clinical and economic burden of wound care in the Tropics via a 5‐year institutional population health review.

2. METHODOLOGY

We conducted a population health analysis of inpatient and outpatient (both specialist and primary care) data from January 2013 to December 2017, at a university tertiary hospital and its affiliated primary care polyclinic system (six polyclinics) within the same healthcare cluster in Singapore. The university tertiary hospital is Singapore's second largest hospital with over 1700 acute inpatient beds and 9000 healthcare staff seeing 2700 outpatient visits and 450 emergency department attendances daily.8 It serves a catchment population of 1.4 million in central Singapore and is part of a healthcare cluster with an affiliated primary care polyclinic system (six polyclinics), which saw more than 2 880 000 primary care outpatient visits in 2017. Clinical, administrative, and healthcare costs data were retrieved from the Population Health Registry using International Classification of Diseases (ICD9 and ICD10) diagnosis codes, surgical procedure codes and service codes (Annex). These data were then correlated with an institutional wound‐specific electronic medical record system (eWounds), which contained more than 500 000 inpatient wound entries between 2013 and 2017.

Within our data analysis, wounds were broadly classified into neuro‐ischaemic ulcers (NIUs), venous leg ulcers (VLUs), pressure injuries (PIs), and surgical site infections (SSI). In Singapore, majority of VLU four‐layer compression bandages are performed by specialist wound nurses in a hospital outpatient setting. Exclusion criteria included patients <21 years old and wounds not verified by eWounds. Variables evaluated include demographic details (gender, age, and ethnicity), clinical variables (Charlson Comorbidity Index [CCI] and Frailty Index), and healthcare administration and economic variables (length of stay, healthcare visit episodes, and healthcare costs). CCI is a method of categorising comorbidities of patients based on the ICD diagnosis codes.9 Each comorbidity category has an associated weight (from 1 to 6), based on the adjusted risk of mortality or resource use and the sum of all the weights results in a single comorbidity score for a patient, which predicts surgical mortality and long‐term survival. The Frailty Index is used to measure the health status of older individuals and it serves as a proxy measure of aging and vulnerability to poor outcomes.10 The factors and outcomes investigated were evaluated using descriptive statistics. All continuous data were expressed as mean ± SD, and categorical data were expressed as percentages (%). The study has been approved by the Institutional Ethics Review Board (NHG DSRB 2019/00977).

3. RESULTS

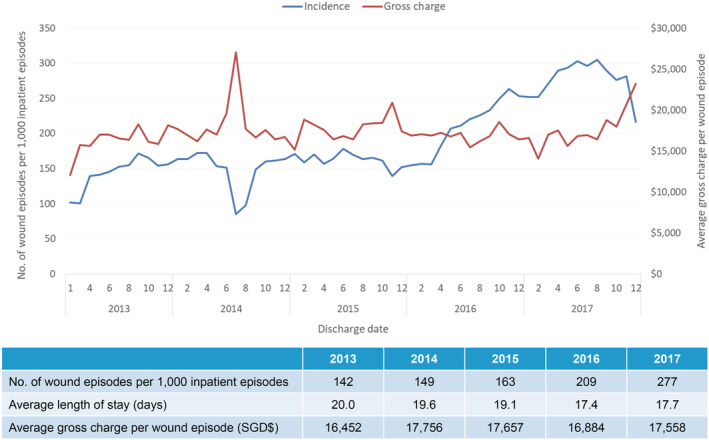

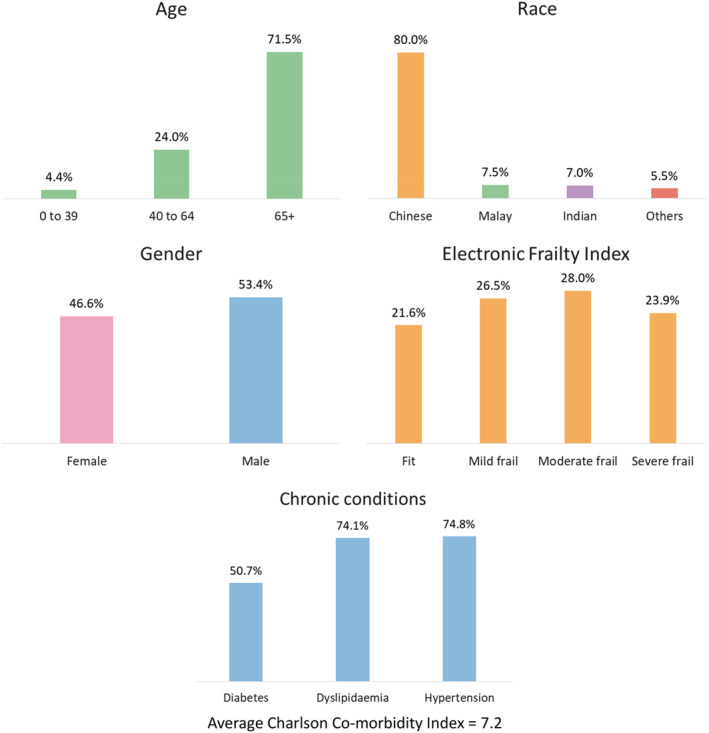

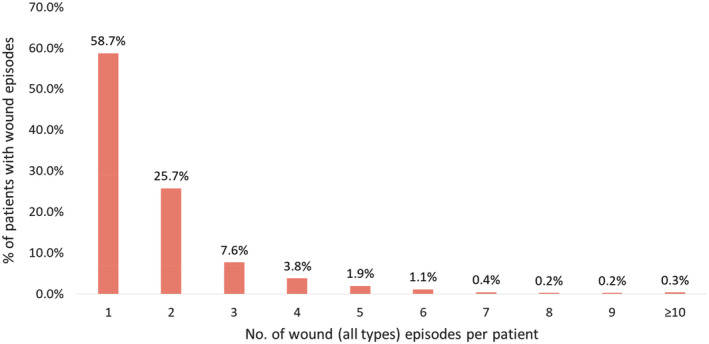

Between 2013 and 2017, there were a total of 56 583 wound‐related inpatient admissions for 41 461 patients, with a 95.1% increase of wound episodes per 1000 inpatient admissions – from 142 to 277 wound episodes per 1000 inpatient admissions in 2013 and 2017, respectively (Figure 1). In 2017, the average length of stay (ALOS) for each wound episode was 17.7 days, with average gross charge per wound episode at USD $12 967 (SGD $17558). Among the 12 218 patients with 16 674 wound episodes in 2017, 71.5% were more than 65 years of age, with an average CCI of 7.2 and with 51.9% of patients either moderately or severely frail (Figure 2). Many (41.3%) had 2 or more wound‐related admission episodes (Figure 3). In 2017, the gross healthcare costs for all inpatient wound episodes was USD $216 million (SGD $293 million) and USD $596 000 (SGD $807000) within primary care settings.

Figure 1.

Incidence of inpatient wound (all types) episodes

Figure 2.

Demographics for inpatient wound (all types) episodes (n = 16 674) discharged in 2017

Figure 3.

Number of wound (all types) episodes per patient with wound episodes discharged in 2017 (total number of patients = 12 218)

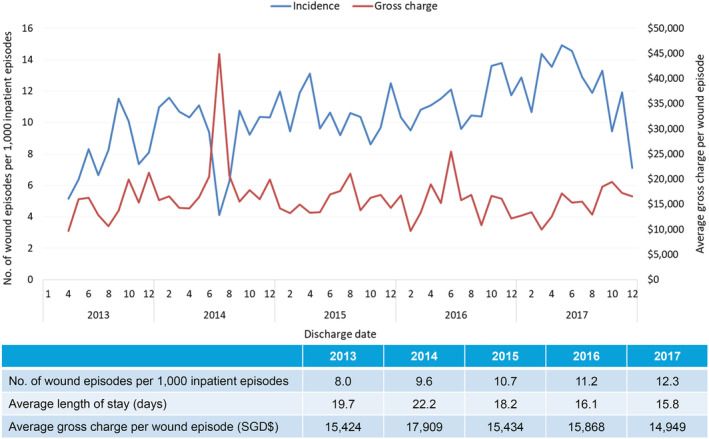

There was a similar rising trend in patients with NIUs (Figure 4). Between 2013 and 2017, there was a 54% increase of eight NIU wound episodes per 1000 inpatient admissions in 2013 to 12.3 wound episodes per 1000 inpatient admissions in 2017. In 2017, for 949 episodes in 633 patients, ALOS was 15.8 days and average gross charge per wound episode was USD $11 045 (SGD $14949). Almost one‐third of patients (30.5%) had two or more NIU‐related admission episodes for the index wound (Table 2). These patients were elderly (55.7% more than 65 years of age), with multiple comorbidities (average CCI 8.4), and were frail (76.8% moderately or severely frail) (Table 1).

Figure 4.

Incidence of inpatient wound (neuro‐ischaemic ulcers) episodes

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics of inpatient wound episodes in 2017

| Neuro‐ischaemic ulcers (NIUs) | Venous leg ulcers (VLUs) | Pressure injuries (PIs) | Surgical site infections (SSIs) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total inpatient episodes | 949 | 112 | 4981 | 2463 |

| Number of patients | 633 | 80 | 3874 | 2176 |

| Incidence per 1000 admissions | 12.3 | 1.5 | 64.6 | 32.0 |

| Average length of stay (days) | 15.8 | 13.0 | 18.6 | 14.9 |

| Average gross charge per episode |

USD$11045 SGD$14949 |

USD$7235 SGD$9792 |

USD$12291 SGD$16636 |

USD$15701 SGD$21252 |

| Total gross inpatient healthcare cost |

USD$10509154 SGD$14186601 |

USD$812417 SGD$1096704 |

USD$61383952 SGD$82863916 |

USD$38775161 SGD$52343676 |

| Age | ||||

| 21–39 | 1.9 | 1.8 | 1.2 | 8.6 |

| 40–64 | 42.4 | 46.4 | 12.2 | 31.2 |

| >65 | 55.7 | 51.8 | 86.5 | 60.2 |

| Gender (%) | ||||

| Male | 63.0 | 57.1 | 45.9 | 54.4 |

| Female | 37.0 | 42.9 | 54.1 | 45.6 |

| Ethnicity (%) | ||||

| Chinese | 58.9 | 67.9 | 89.5 | 79.4 |

| Malay | 15.7 | 6.3 | 4.1 | 7.6 |

| Indian | 17.0 | 16.1 | 2.7 | 6.9 |

| Others | 8.4 | 9.8 | 3.8 | 6.0 |

| Comorbidities (%) | ||||

| Diabetes | 97.2 | 49.1 | 48.4 | 37.1 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 95.4 | 75.0 | 75.5 | 64.2 |

| Hypertension | 94.1 | 67.9 | 77.3 | 62.8 |

| Average Charlson Comorbidity Index | 8.4 | 5.2 | 8.3 | 5.9 |

| Electronic Frailty Index (%) | ||||

| Fit | ||||

| Mild Frail | 5.9 | 22.3 | 10.6 | 44.1 |

| Moderate Frail | 17.3 | 25.9 | 26.2 | 29.8 |

| Severe Frail | 31.9 | 26.8 | 33.5 | 18.6 |

| 44.9 | 25.0 | 29.7 | 7.5 |

On hospital specialist outpatient follow‐up in 2017, there were a total of 1236 outpatient episodes for neuro‐ischaemic wounds, with average gross charge per episode at USD $176 (SGD $238) (Table 2). On primary care follow‐up in 2017 for related NIU, 159 patients (25.1%) required more than 1 primary care wound‐related visit, with conditional average number of primary care wound visits within 1‐year from discharge at 3.1, and the conditional average gross charge of primary care wound visits at USD $146 (SGD$197). The estimated gross healthcare costs per patient for hospital care (in‐patient and specialist outpatient) and primary care in 2017 was USD $16 920 (SGD $22926).

Table 2.

Outcomes for patients discharged from tertiary care admissions in 2017

| Neuro‐ischaemic ulcers (NIUs) | Venous leg ulcers (VLUs) | Pressure injuries (PIs) | Surgical site infections (SSIs) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital inpatient data | ||||

| Total inpatient episodes | 949 | 112 | 4981 | 2463 |

| Number of patients | 633 | 80 | 3874 | 2176 |

| Average gross charge per episode |

USD$11045 SGD$14949 |

USD$7235 SGD$9792 |

USD$12291 SGD$16636 |

USD$15701 SGD$21252 |

| Total gross inpatient healthcare cost |

USD$10509154 SGD$14186601 |

USD$812417 SGD$1096704 |

USD$61383952 SGD$82863916 |

USD$38775161 SGD$52343676 |

| 1‐year re‐admissions | ||||

| Number of patients with 2 or more wound episodes (percentage) | 193 (30.5) | 19 (23.5) | 775 (20.0) | 257 (11.8) |

| Hospital outpatient follow‐up | ||||

| Number episodes | 1236 | 5791 | N/A | N/A |

| Average gross charge per episode |

USD$176 SGD$238 |

USD$92 SGD$124 |

N/A | N/A |

| Total gross hospital outpatient healthcare cost |

USD$217914 SGD$294168 |

USD$531942 SGD$718084 |

N/A | N/A |

| Primary care outpatient follow‐up | ||||

| Number of patients | 633 | 80 | 3874 | 2176 |

| Number of patients with more than 1 wound visit (percentage) | 159 (25.1) | 17 (21.3%) | 147 (3.8) | 275 (12.6) |

| Conditional average number of wound visits within 1‐year postdischarge | 3.1 | 1.7 | 1.3 | 1.5 |

| Conditional average gross charge of primary care wound visits within 1‐year postdischarge |

USD$146 SGD$197 |

USD$93 SGD$125 |

USD$91 SGD$123 |

USD$66 SGD$89 |

| Total gross primary healthcare cost |

USD$23219 SGD$31344 |

USD$1569 SGD$2118 |

USD$13422 SGD$18119 |

USD$18217 SGD$24591 |

| Estimated gross healthcare cost per patient | ||||

| Hospital care (inpatient only) and primary care |

USD$16639 SGD$22461 |

USD$10175 SGD$13735 |

USD$15789 SGD$21394 |

SGD$17761 SGD$24066 |

| Hospital care (inpatient and outpatient) and primary care |

USD$16920 SGD$22926 |

SGD$16761 SGD$22711 |

N/A | N/A |

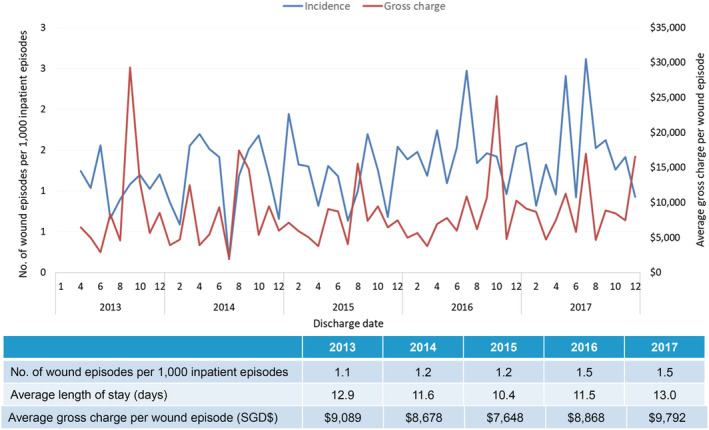

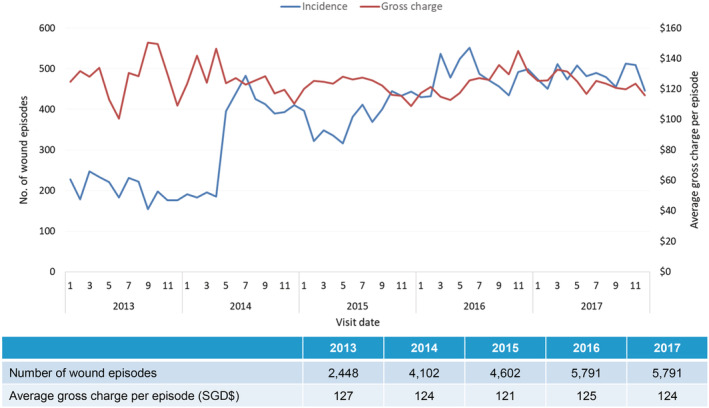

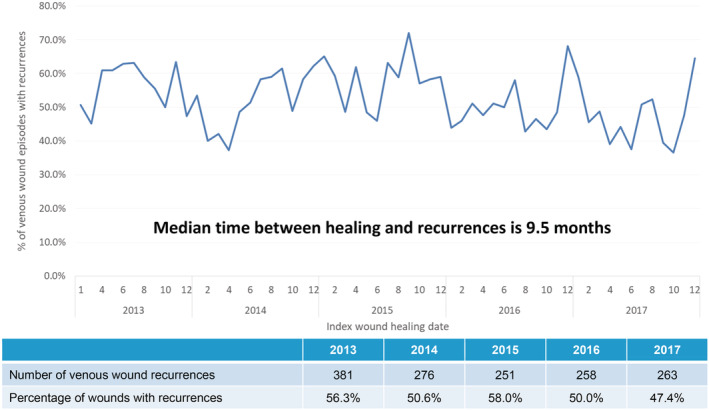

In patients with VLUs, the incidence of inpatient VLU episodes, ALOS, and average gross charge per wound episode was fairly stable from 2013 to 2017, with incidence at 1.5 wound episodes per 1000 inpatient episodes, ALOS at 13 days and average gross charge at USD $7235 (SGD $9792) per wound episode (Figure 5). These patients were less elderly (51.8% more than 65 years of age), with lesser comorbidities (average CCI 5.2) and less frail (51.8% moderately or severely frail) (Table 1). Over a quarter (23.8%) of the patients had two or more VLU‐related re‐admissions for the index wound (Table 2). Significantly, the majority of the clinical burden is in the specialist outpatient setting, with an increasing trend of 2448 VLU‐related wound episodes in 2013 to 5791 in 2017, with average gross charge per episode stable at USD $92 (SGD $124) (Figure 6). Between 2013 and 2017, the average 1‐year VLU recurrences rate was 52.5%, with median time between healing and recurrences at 9.5 months (Figure 7). The estimated gross healthcare costs per patient for hospital care (inpatient and specialist outpatient) and primary care in 2017 was USD $16 761 (SGD $22711) (Table 2).

Figure 5.

Incidence of inpatient wound (venous leg ulcers) episodes

Figure 6.

Incidence of tertiary care outpatient wound (venous leg ulcers) episodes

Figure 7.

Incidence of tertiary care outpatient wound (venous leg ulcers) recurrences

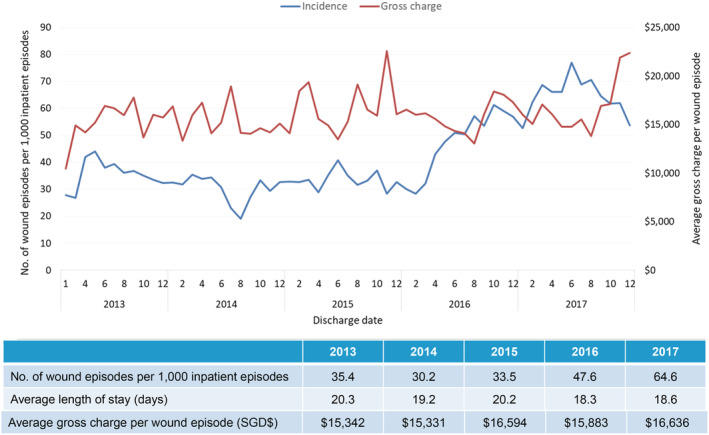

For PIs, there was an 82% increase of 35.4 PI wound episodes per 1000 inpatient admissions in 2013 to 64.6 wound episodes per 1000 inpatient admissions in 2017. In 2017, for 3874 patients with 4981 PI wound episodes, ALOS was 18.6 days and average gross charge per wound episode was USD $12 291 (SGD $16636) (Figure 8). Both ALOS and average gross charge per wound episode was stable from 2013 to 2017. Expectedly, these patients were the most elderly (86.5% more than 65 years of age), with multiple comorbidities (average CCI 8.3) and were very frail (63.2% moderately or severely frail) (Table 1). One fifth (20.0%) of patients had two or more PI‐related re‐admissions for the index wound (Table 2). On 1‐year follow‐up, the all‐cause mortality rate was 14.3%, with 26.8% of patients institutionalised (either community hospitals or nursing homes) upon discharge from the tertiary hospital. The estimated gross healthcare costs per patient for hospital care (inpatient only) and primary care in 2017 was USD $15 789 (SGD $21394).

Figure 8.

Incidence of inpatient wound (pressure injuries) episodes

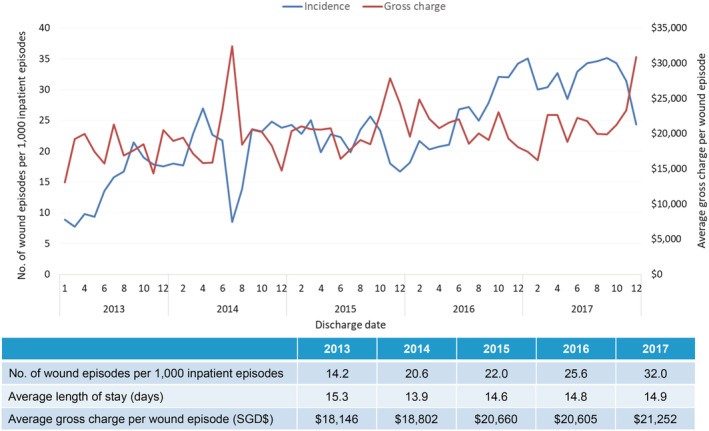

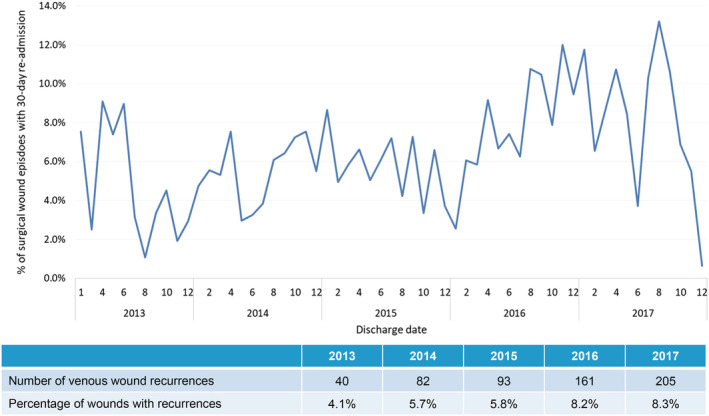

For SSIs, there was a 125% increase of 14.2 wound episodes per 1000 inpatient admissions in 2013 to 32.0 in 2017, with ALOS stable at 14.9 days and average gross charge per wound episode stable at USD $15 701 (SGD $21252) from 2013 to 2017 (Figure 9). Significantly, there was a 413% increase in wound‐related 30‐day re‐admission, from 40 in 2013 (4.1% of all surgeries) to 205 (8.3% of all surgeries) in 2017 (Figure 10). These patients were also elderly (60.2% more than 65 years of age) but with slightly less comorbidities (average CCI 5.9) and less frail (26.1% moderately or severely frail) (Table 1). The estimated gross healthcare costs per patient for hospital care (inpatient only) and primary care in 2017 was USD $17 761 (SGD $24066).

Figure 9.

Incidence of inpatient wound (postoperative surgical) episodes

Figure 10.

Incidence of 30‐day re‐admissions for postoperative surgical wound episodes

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Clinical and economic burden of wounds in the Tropics

This is the first paper from the Tropics to comprehensively evaluate the clinical and economic burden of various wounds types at an institutional population health level. Within Western societies the burden of chronic wounds has been well described. In the US, it is estimated that 8.2 million Medicare beneficiaries had at least one type of wound, with the financial burden to Medicare ranging from USD $28.1 billion to USD $96.8 billion in 2014.3 Between 2012 and 2013, Wales was estimated to have a chronic wound prevalence of 6%, amounting to 5.5% of the National Health Service expenditure.4 In 2012, the cost associated with wound management in the UK was estimated at £4.5–5.1 billion.5 In Australia, the direct health care costs of chronic wounds were estimated at A$3 billion a year, which constitutes approximately 2% of Australian national health care expenditure.11

Chronic wounds are often under‐reported, as they are considered complications of other diseases.12 This is further compounded by the lack of data from the Tropics. Our data show that there is a similar heavy clinical burden of wound care within the Tropics. From 2013 to 2017, there was a significant 95.1% increase of 142 wound episodes per 1000 inpatient admissions to 277 wound episodes per 1000 inpatient admissions. ALOS for each wound episode was 17.7 days, which is 2.4 times that of ALOS within our institution (7.3 days for an average acute admission).8 Furthermore, there was a high re‐admission rate, with 41.3% of patients requiring two or more wound‐related admissions within the year.

In a similar but smaller study conducted at another local tertiary hospital, which retrospectively looked at 470 patients (with diabetic, pressure venous, ischaemic, and unspecified chronic skin ulcers) over 2 years between 2012 and 2013, the ALOS was 13.2 days and the estimated gross direct cost per patient was SGD $19 532.13 Their ALOS and estimated cost is similar to findings from our current study. In 2017, average gross charge per wound episode within our institution was SGD $17 558 (USD $12967) and the total gross healthcare costs for all inpatient wound episodes stand at SGD $293 million (USD $216 million) within tertiary care and SGD $807 000 (USD $596000) within primary care. Similar to data from Western societies, this not only demonstrates a significant clinical and economic burden of chronic wounds in the Tropics, but also highlights a worsening issue. Data from this report will help guide local healthcare policies so as to improve health service coordination and funding for wound care. For example in Sweden, an intervention in a population of 150 000 that utilised a wound healing centre, multidisciplinary care and continuous education reduced annual costs of wound care by SEK 6.96 million over a 10‐year period.14

In a 2019 systematic review and meta‐analysis of 17 observational studies on the prevalence of chronic wounds in the general population, chronic wounds were more prevalent in women (range: 53%‐68%).7 However, the selected studies were all based on Western data, with the only study from the Tropics (Indonesia) not stratifying wound prevalence by sex,15 while data from China reported a higher proportion of chronic wounds among men (65%).16 Within our study population, of which 80% were of Chinese ethnicity, there is a higher incidence of chronic wounds among men (53%). Data from the literature also state that chronic wounds are mostly seen in the elderly17 and often occur with other comorbidities.12 Within our study population, 71.5% were more than 65 years of age, with average CCI of 7.2 and with 51.9% of patients either moderately or severely frail. High CCI predicts high surgical mortality and poor long‐term survival while frailty serves as a proxy measure of aging and vulnerability to poor outcomes.9, 10

4.2. Neuro‐ischaemic ulcers

Worldwide, there are around 422 million people living with diabetes, with a prevalence of 8.5% in 2014.18 Among diabetics, the lifetime risk of developing a diabetic foot ulcer (DFU) is estimated at 15% to 25%.19 DFUs constitute the majority of foot NIUs, with smoking‐related peripheral arterial disease being the other significant cause. Within our study population, 97.2% of patients with NIU suffer from diabetes. In Singapore, the prevalence of diabetes was 8.6% in 2017, with an estimated SGD $1billion spent per year on the disease.20 From 2008 to 2013, there has been an increase of diabetes‐related lower extremity amputations (LEAs) from 11.0 per 100 000 population to 13.3 per 100 000, with an estimated four diabetes‐related LEA per day in Singapore.21 Within our institution, we perform around 400 diabetic limb salvage procedures per year, with patients often presenting late in their DFU disease (73% presented with Rutherford 6 critical limb ischaemia).22 Within our study, we see a 54% increase of eight NIU wound episodes per 1000 inpatient admissions in 2013 to 12.3 wound episodes per 1000 inpatient admissions in 2017, with 30.5% of patients requiring two or more NIU‐related admission episodes for the index wound. The estimated gross healthcare cost per patient for hospital care (inpatient and specialist outpatient) and primary care in 2017 was SGD $22 926 (USD $16920). As compared with the other wound groups, NIU patients have the most comorbidities (average CCI 8.4) and are the frailest group of patients (76.8% moderately or severely frail). Within the literature, NIU foot wound care has the strongest evidence for a multi‐disciplinary team (MDT) approach, with both National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and International Working Group on Diabetic Foot guidelines stating that “a multi‐disciplinary foot care team and implementing prevention and management of diabetic foot disease according to the guidelines, is associated with a decrease in the frequency of diabetes related lower‐extremity amputations.”23, 24

In the US, the total direct cost for healing of infected DFUs not requiring amputation was estimated at USD $17 500 per patient (in 1998), whereas the cost for lower‐extremity amputations was between USD $30 000–$33 500 (depending on the level of amputation) per patient.25 In a patient with DFU, it was estimated that the potential economic benefits of LEA prevention strategies is between USD $2900–$4442 per patient over 3 years.26 Within our study, the NIU estimated gross healthcare cost per patient for hospital care (inpatient and specialist outpatient) and primary care in 2017 was USD $16 920 (SGD $22926). Diabetic limb salvage attempts not only involve multi‐disciplinary care, it usually also involves aggressive therapies such as revascularisation procedures, advanced wound healing modalities and off‐loading products. Although collectively these interventions are costly, the MDT approach leads to improved screening, prevention programs and earlier interventions, which will translate to reduced long‐term costs.27

4.3. Venous leg ulcers

Venous leg ulceration occurs secondary to venous reflux or obstruction and it affects up to 3 in 1000 people. Prevalence increases with age to about 20 in 1000 people over the age of 80 years.28 In the UK, prevalence is up to 3% in patients over the age of 65 while in the US, 10%‐35% of adults suffer from chronic venous insufficiency, with 4% of patients over the age of 65 suffering from VLU.29, 30 Around the world, prevalence of VLU per 1000 population per year ranges from 4.5 in India, 1.7 in China, 1.5 in Brazil to 1.2 in Australia.16, 31, 32, 33 Within our institution, although the incidence of VLU per 1000 admissions had been stable from 2013 to 2017 (1.5 per 1000 admissions in 2017), the majority of the disease burden was at the specialist outpatient clinics, where there was an increasing trend of 2448 VLU‐related wound episodes in 2013 to 5791 in 2017. In Singapore, majority of four‐layer compression bandages are performed by specialist wound nurses in the specialist outpatient setting. In addition, VLU healing is variable and recurrence is common.34 In the UK, 53% of VLU heal within 1‐year, with mean time to healing of 3 months.35 Between 2013 and 2017, our average 1‐year VLU recurrence rate was 52.5%, with median time between healing and recurrence at 9.5 months.

From a socio‐economic perspective, the chronicity of VLU has a negative impact on quality of life and results in considerable costs to both patients and healthcare providers. In the US, VLU treatment costs were estimated at more than USD $2.5 billion per year,30 while in UK VLU treatment is estimated at £300‐600million per year, which was about 1% of the national healthcare budget.34 The annual cost per VLU patient in UK was estimated at £10 000–30 000 per year. Within our study population, although the hospital inpatient economic burden of VLU was lower than other wound types (average gross charge per inpatient episode at USD $7235 [SGD $9792] for VLU), most of the follow‐up was at the specialist outpatient and primary care setting. As a result, the VLU estimated gross healthcare cost per patient for both hospital care (inpatient and specialist outpatient) and primary care was USD $16 761 (SGD $22711), which was similar to that for other wound types. In the UK, the cost of wound care over 1 year for managing an unhealed VLU was 4.5 times more than that of managing a healed VLU (at £3000 per healed and £13 500 per unhealed ulcer).35 Recent cost‐effectiveness analysis of a randomised clinical trial of early versus deferred endovenous ablation of superficial venous reflux in patients with venous ulceration showed that early treatment of superficial reflux is highly likely to be cost‐effective in patients with VLUs over 1 year.36 Hence, for VLU, there is potentially a large margin for cost‐savings through improving clinical treatment, improving wound‐healing rates and decreasing recurrence rates.

4.4. Pressure injuries

It is well established that PIs have significant impact on a patient's well‐being and a country's healthcare costs. In the 1990s, treatment of PI cost the US healthcare system USD $8.5 billion annually.37 Between 1999 and 2000, the total cost of PI in UK was estimated at £1.4–2.1 billion annually (4% of total National Health Service expenditure).38 A more contemporary audit of all patients within the acute and community inpatient settings in Wales (n = 8365 patients) in 2015 revealed a pressure ulcer prevalence rate of 8.9%, of which half were acquired in the hospital setting.39 In Singapore, at a study conducted at our institution in 2002, the prevalence of pressure ulcers was 18.1% with an incidence of 8.1%.40 Within our current study population, PI constituted the largest cohort of patients with wounds. In 2017, there were 3874 PI patients with an incidence of 64.6 per 1000 admissions, with the estimated gross healthcare costs per patient for hospital care (inpatient only) and primary care in 2017 at USD $15 789 (SGD $21394), which was similar to the other wound categories.

The population in Singapore is aging rapidly. In 2018, 13.7% of the population was aged 65 years or older, but according to a United Nations 2019 report this proportion is expected to increase to 47% in 2050.41 With a growing elderly population with accompanying comorbidities, there will be a higher prevalence of PI and a resultant decrease in quality of life and prolonged hospitalisation. Elderly patients with PI have a fourfold increase in the risk of death.42 Similar to data from the literature, PI patients within our study population have multiple comorbidities (average CCI 8.3) and were the most elderly, with 86.5% more than 65 years of age. As a result, they had the longest ALOS at 18.6 days per episode, as compared with other wound types. The 1‐year all‐cause mortality rate was 14.3%, with 26.8% of patients institutionalised (either community hospitals or nursing homes) upon discharge from hospital. In accordance to NICE guidelines, institutions must continue to perform PI risk assessment, skin assessment, perform care planning, encourage repositioning, adopt devices for PI prevention and provide healthcare professional training and education in the prevention and management of pressure ulcers.43

4.5. Surgical site infections

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), an SSI is an infection that occurs after surgery in the part of the body where the surgery took place.44 Superficial SSI involves the skin and subcutaneous tissue only, deep SSI involves deep soft tissues (fascia and muscle), while organ/space SSI involves any part of the body deeper than the fascia/muscle layers that is opened or manipulated during the operative procedure. A 2009 study estimated an incidence of 2% to 5% for SSI in the US.45 In 2014, there were 14.2 million operations performed as inpatient procedures in US hospitals,46 while a CDC healthcare‐associated infection (HAI) prevalence survey found that there were an estimated 110 800 SSI associated with inpatient surgeries in 2015.47 Worldwide, the prevalence of SSI is difficult to ascertain because of a lack of diagnosis standardisation, variability of available resources across developing and developed countries, and heterogeneity of surgical procedures. However, a 1998 international survey on the prevalence of hospital‐acquired infection estimated the prevalence of SSI to range from 5.2% to 34.4%.48 Despite advances in infection control practices, technology, and antimicrobial prophylaxis, SSI remains a substantial cause of morbidity, with an associated mortality rate of 3%.49

Within our study population there was a 125% increase of 14.2 SSI wound episodes per 1000 inpatient admissions in 2013 to 32.0 in 2017. Furthermore, there was a 413% increase in wound‐related 30‐day re‐admission, from 40 in 2013 (4.1% of all surgeries) to 205 (8.3% of all surgeries) in 2017. In a 2013 systematic review of risk factors associated with SSI among surgical patients, risk factors for SSI include reduced fitness, patient frailty, surgery duration, and complexity.50 To address and decrease the clinical burden of SSI, recognition of these risk factors helps identify at‐risk patients to focus peri‐operative optimisation efforts. The World Health Organisation's (WHO) 21‐point guideline recommendations in preventing SSI must be adopted, as it covers a comprehensive preoperative preparation (including the cessation of immunosuppressive medications and nutrition optimisation), intra‐operative considerations (including warming devices and blood glucose control), and postoperative management best practices (including use of wound drains and advanced dressings).51 In addition, surveillance of SSI with appropriate feedback of data to surgeons has also been shown to be an effective strategy to reduce SSI risks.52

Economically, SSI is the most costly HAI type with an estimated annual cost of USD $3.3 billion and nearly 1 million additional inpatient‐days annually in the US.53 It is estimated that 60% of SSIs are preventable; hence, institutional quality improvement programs in the US often target SSI as a key “pay‐for‐performance” metric.54 For example, since 2008, the US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services are no longer reimbursing hospitals for HAI such as SSI.55 Within our study, the estimated gross healthcare cost per patient for both hospital care (inpatient only) and primary care in 2017 was USD $17 761 (SGD $24066), which was similar to the other wound categories. Efforts to reduce the clinical and economic burden of SSI must not only be based upon clinical evidence, but also incentivised financially. Only then will the reduction of the clinical and economic burden of SSI be beneficial on a tripartite front, for patients, clinicians, and healthcare systems.

Limitations of our study include its registry‐based retrospective design from a single healthcare cluster, with associated selection and information biases. Results may not be generalisable to other regions in the Tropics or Asia. Wound‐related admissions at tertiary care were well coded but wound‐related presentations at primary care was lacking. Hence, contrary to studies from UK or US,3, 4, 5 our study population was identified from tertiary care, instead of primary care. Separately, chronic wounds are often under‐reported, as they are considered complications of other diseases. These comorbidities may result in misclassification bias in terms of diagnosis codes, surgical procedure codes or service codes. Given that all included studies presented prevalence of wounds detected within the healthcare system, self‐treated cases, especially those in the outpatient setting, were not reported. Also, as described, we evaluated only the four major wound categories of NIU, VLU, PI, and postoperative surgical wounds and did not analyse other wound types such as fungating tumours, traumatic, and burn wounds. Given that this study was designed to be an institutional population health overview on the clinical and economic burden of various chronic wounds in the Tropics, we did not stratify and perform sub‐group analysis on each wound type. However, in‐depth analysis for each wound type of NIU, VLU, PI, and postoperative surgical wounds will be addressed in future publications.

5. CONCLUSION

Similar to global data, there is a significant and rising trend in the clinical and economic burden of wound care in the Tropics. In 2017, more than one in four inpatient admissions had wound‐related issues, with ALOS 2.4 times that of an average tertiary hospital admission and an average gross charge per wound episode at USD $12 967 (SGD $17558). These patients are elderly, with multiple comorbidities and are frail. A multi‐disciplinary and institutional strategy must be adopted to reduce this clinical and economic burden, such that benefits on a tripartite front, for patients, clinicians, and healthcare systems, may be achieved.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The research was partially supported through grant funding from the Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR) under its Industry Alignment Fund – Pre‐Positioning Programme (IAF‐PP) grant number H18/01/a0/ZZ9 as part of Wound Care Innovation for the Tropics (WCIT) Programme. All authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

Lo ZJ, Lim X, Eng D, et al. Clinical and economic burden of wound care in the tropics: a 5‐year institutional population health review. Int Wound J. 2020;17:790–803. 10.1111/iwj.13333

All authors contributed sufficiently to be credited as co‐authors.

Funding information Agency for Science, Technology and Research, Grant/Award Number: H18/01/a0/ZZ9

REFERENCES

- 1. Kyaw BM, Järbrink K, Martinengo L, Car J, Harding K, Schmidtchen A. Need for improved definition of “chronic wounds” in clinical studies. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98:157‐158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sen CK, Roy S, Gordillo G. Wound Healing (Neligan Plastic Surgery: Volume One). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nussbaum SR, Carter MJ, Fife CE, et al. An economic evaluation of the impact, cost, and medicare policy implications of chronic non‐healing wounds. Value Health. 2018;21:27‐32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Phillips CJ, Humphreys I, Fletcher J, Harding K, Chamberlain G, Macey S. Estimating the costs associated with the management of patients with chronic wounds using linked routine data. Int Wound J. 2015;13:1193‐1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Guest JF, Ayoub N, McIlwraith T, et al. Health economic burden that different wound types impose on the UK's National Health Service. Int Wound J. 2017;14:322‐330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Olsson M, Järbrink K, Divakar U, et al. The humanistic and economic burden of chronic wounds: a systematic review. Wound Rep Reg. 2019;27:114‐125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Martinengo L, Olsson M, Bajpai R, et al. Prevalence of chronic wounds in the general population: systematic review and meta‐analysis of observational studies. Ann Epidemiol. 2019;29:8‐15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. National Healthcare Group Corporate Yearbook FY2018. https://corp.nhg.com.sg/Lists/Corporate%20Year%20Book/Attachments/67/NHG%20Yearbook%202019%20Lowres%20Single1.pdf Accessed December 2019.

- 9. Charlson ME, Pompei PA, Kathy L, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373‐383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Searle SD, Mitnitski A, Gahbauer EA, Gill TM, Rockwood K. A standard procedure for creating a frailty index. BMC Geriatr. 2008;8:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Graves N, Zheng H. Modelling the direct health care costs of chronic wounds in Australia. Wound Prac Res: J Aust Wound Manage Assoc. 2014;22(1):20‐24. 6–33. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sen CK, Gordillo GM, Roy S, et al. Human skin wounds: a major and snowballing threat to public health and the economy. Wound Repair Regen: Off Publ Wound Healing Soc [and] Eur Tissue Repair Soc. 2009;17(6):763‐771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tan BK, Tan EWX, Chong SJ, Chang YY, Song C, Lee VJ. An economic evaluation of chronic wound management in a tertiary hospital. Wound Prac Res. 2016;24(3):130‐136. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Öien R, Ragnarson TG. Accurate diagnosis and effective treatment of leg ulcers reduce prevalence, care time and costs. J Wound Care. 2006;15(6):259‐262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Amir Y, Lohrmann C, Halfens RJ, Schols JM. Pressure ulcers in four Indonesian hospitals: prevalence, patient characteristics, ulcer characteristics, prevention and treatment. Int Wound J. 2017;14(1):184e93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jiang Y, Huang S, Fu X, et al. Epidemiology of chronic cutaneous wounds in China. Wound Repair Regen. 2011;19(2):181e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gould L, Abadir P, Brem H, et al. Chronic wound repair and healing in older adults: current status and future research. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:427‐438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. World Health Organization Fact Sheet on Diabetes. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diabetes. Accessed December 2019

- 19. Amin N, Doupis J. Diabetic foot disease: from the evaluation of the “foot at risk” to the novel diabetic ulcer treatment modalities. World J Diabetes. 2016;7:153‐164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ministry of Health Singapore . Prevalence of Diabetes in Singapore. https://data.gov.sg/dataset/prevalence-of-hypertension-diabetes-high-total-cholesterol-obesity-and-daily-smoking. Accessed December 2019

- 21. Ang Y, Yap CW, Saxena N, Lin LK, Heng BH. Diabetes‐related lower extremity amputations in Singapore. Proc Singapore Healthcare. 2017;26(2):76‐80. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lo ZJ, Lin Z, Pua U, et al. Diabetic foot limb salvaged—a series of 809 attempts and predictors for endovascular limb salvage failure. Ann Vasc Surg. 2018;49:9‐16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Diabetic foot problems: prevention and management. National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng19 Accessed December 2019 [PubMed]

- 24. International Working Group on Diabetic Foot (IWGDF) 2019 guidelines. https://www.iwgdfguidelines.org. Accessed December 2019

- 25. Tennvall GR. Apelqvist. Health‐economic consequences of diabetic foot lesions. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39(2):S132‐S139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ollendorf DA, Kotsanos JG, Wishner WJ, et al. Potential economic benefits of lower‐extremity amputation prevention. Diabetes Care. 1998;21(8):1240‐1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Driver VR, Fabbi M, Lavery LA, Gibbons G. The costs of diabetic foot: the economic case for the limb salvage team. J Vasc Surg. 2010;52:17S‐22S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nelson EA, Adderley U. Venous leg ulcers. BMJ Clin Evid. 2016;1902:1902‐1938. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Callam MJ, Ruckley CV, Harper DR, Dale JJ. Chronic ulceration of the leg: the extent of the problem and the provision of care. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1985;290:1855‐1856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lal BK. Venous ulcers of the lower extremity: definition, epidemiology and economic and social burdens. Semin Vasc Surg. 2015;28(1):3‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shukla VK, Ansari MA, Gupta SK. Wound healing research: a perspective from India. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2005;4(1):7‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Faria E, Blanes L, Hochman B, Filho MM, Ferreira L. Health‐related quality of life, self‐esteem, and functional status of patients with leg ulcers. Wounds. 2011;23(1):4‐10. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Baker SR, Stacey MC. Epidemiology of chronic leg ulcers in Australia. Aust N Z J Surg. 1994;64(4):258‐261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nelson EA, Bell‐Syer SE. Compression for preventing recurrence of venous ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;9(9):CD002303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Guest JF, Fuller GW, Vowden P. Venous leg ulcer management in clinical practice in the UK: costs and outcomes. Int Wound J. 2017;15(1):29‐37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Epstein DM, Gohel MS, Heatley F, et al. Cost‐effectiveness analysis analysis of a randomized clinical trial of early versus deferred endovenous ablation of superficial venous reflux in patients with venous ulceration. BJS. 2019;106(5):555‐562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kuhn B, Coulter S. Balancing the pressure sore cost and quality education. Nursing Economics. 1992;10(5):353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bennett G, Dealey C, Posnett J. The cost of pressure ulcers in the UK. Age Ageing. 2004;33(3):230‐235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Clark M, Semple MJ, Ivins N, Mahoney K, Harding K. National audit of pressure ulcers and incontinence associated dermatitis in hospitals across Wales: a cross‐sectional study. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e015616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chan EY, Tan SL, Lee CK, Lee JY. Prevalence, incidence and predictors of pressure ulcers in a tertiary hospital in Singapore. J Wound Care. 2005;14(8):383‐388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. United Nations Would Population Ageing 2019. https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/ageing/WorldPopulationAgeing2019-Highlights.pdf Accessed December 2019

- 42. Burd C, Langemo D, Olson B, Hanson D, Hunter S, Sauvage T. Skin problem: epidemiology of pressure ulcers in a skilled care facility. J Gerontol Nurs. 1992;18(9):29‐39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pressure ulcers: prevention and management. National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg179 Accessed December 2019

- 44. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Surgical Site Infection (SSI). https://www.cdc.gov/hai/ssi/ssi.html. Accessed December 2019

- 45. McDermott KW, Freeman WJ, Elixhauser A. Overview of Operating Room Procedures During Inpatient Stays in U.S. Hospitals, 2014. HCUP Statistical Brief #233. December 2017. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. https://www.hcup‐ us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb233-Operating-Room-Procedures-United-States‐ 2014.jsp. Accessed December 2019 [PubMed]

- 46. Anderson DJ, Kaye KS. Staphylococcal surgical site infections. Infec Dis Clini North Am. 2009;23:53‐72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Magill SS, Erin O'L, Janelle SJ, Thompson DL, Dumyati G, et al. Changes in prevalence of health care‐associated infection in U.S. hospitals. New Engl J Med. 2018;379(18):1732‐1744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Mayon‐White RT, Ducel G, Kereselidze T, Tikomirov E. An international survey of the prevalence of hospital‐acquired infection. J Hosp Infect. 1988;11:S43‐S48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Awad SS. Adherence to surgical care improvement project measures and postoperative surgical site infections. Surg Infec. 2012;13(4):234‐237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Korol E, Johnston K, Waser N, et al. A systematic review of risk factors associated with surgical site infections among surgical patients. PloS ONE. 2013;8(12):e83743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. World Health Organization global guidelines for the prevention of surgical site infection https://www.who.int/gpsc/SSI-outline.pdf?ua=1. Accessed December 2019

- 52. Berríos‐Torres SI, Umscheid CA, Bratzler DW, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guideline for the prevention of surgical site infection. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(8):784‐791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Zimlichman E, Henderson D, Tamir O, Franz C, Song P, et al. Health care‐associated infections. A meta‐analysis of costs and financial impact on the US health care system. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(22):2039‐2046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ban KA, Minei JP, Laronga C, Harbrecht BG, Jensen EH, et al. American College of Surgeons and surgical infection society: surgical site infection guidelines, 2016 update. J Am Coll Surg. 2017;1:59‐74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Stone PW. Changes in Medicare reimbursement for hospital‐acquired conditions including infections. Am J Infect Control. 2009;37:17A‐18A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]