ABSTRACT

Background

Carotenoids represent 1 of few modifiable factors to reduce breast cancer risk. Elucidation of interactions between circulating carotenoids and genetic predispositions or mammographic density (MD) may help inform more effective primary preventive strategies in high-risk populations.

Objectives

We tested whether women at high risk for breast cancer due to genetic predispositions or high MD would experience meaningful and greater risk reduction from higher circulating levels of carotenoids in a nested case-control study in the Nurses’ Health Studies (NHS and NHSII).

Methods

This study included 1919 cases and 1695 controls in a nested case-control study in the NHS and NHSII. We assessed both multiplicative and additive interactions. RR reductions and 95% CIs were calculated using unconditional logistic regressions, adjusting for matching factors and breast cancer risk factors. Absolute risk reductions (ARR) were calculated based on Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results incidence rates.

Results

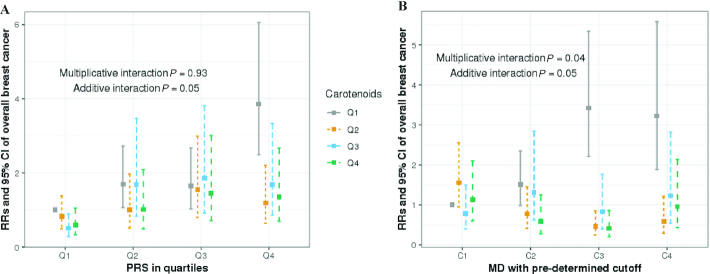

We showed that compared with women at low genetic risk or low MD, those with higher genetic risk scores or high MD had greater ARRs for breast cancer as circulating carotenoid levels increase (additive P-interaction = 0.05). Among women with a high polygenic risk score, those in the highest quartile of circulating carotenoids had a significant ARR (28.6%; 95% CI, 14.8–42.1%) compared to those in the lowest quartile of carotenoids. For women with a high percentage MD (≥50%), circulating carotenoids were associated with a 37.1% ARR (95% CI, 21.7–52.1%) when comparing the highest to the lowest quartiles of circulating carotenoids.

Conclusions

The inverse associations between circulating carotenoids and breast cancer risk appeared to be more pronounced in high-risk women, as defined by germline genetic makeup or MD.

Keywords: carotenoids, breast cancer, genetic risk, mammography density, absolute risk

See corresponding editorial on page 499.

Introduction

Breast cancer is the leading malignant disease in women worldwide. Globally, an estimated 2.1 million new cases of breast cancer were diagnosed in 2018, accounting for 12% of all newly diagnosed cancer cases (1). Advances in germline genetic profiling and mammographic screening underscore the complexity of breast cancer susceptibility and provide useful tools to identify those women at greater risk even decades before a breast cancer diagnosis. However, substantial gaps in knowledge remain. Despite the existence of clinical breast cancer prevention options (such as mastectomy, salpingo-oophorectomy, chemoprevention with tamoxifen, and more intensive screening), for women categorized as high risk, there are limited noninvasive, personal-level recommendations for women to help them reduce their breast cancer risk.

Carotenoids—a family of naturally occurring lipophilic compounds found in fruits and vegetables—represent 1 of the few personal-level modifiable risk factors for primary cancer prevention, and are associated with a lowered breast cancer risk (2–6). Compelling experimental evidence shows that carotenoid derivatives and metabolites display anticarcinogenic activities, and could reduce cell growth and differentiation (7), activate a protein kinase cascade (7), and trigger growth inhibition (8). Accumulating epidemiological evidence has also linked dietary and circulating carotenoids with a reduced risk of breast cancer (2–5, 9–12). Meta-analyses from large-scale prospective cohorts showed that higher dietary and circulating levels of carotenoids were associated with lowered breast cancer risk, and those associations were particularly evident for estrogen receptor (ER)–negative tumors (2). In the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS), total plasma carotenoid concentrations—measured 1 month to 20 years before diagnosis—were associated with a 21% lower risk of breast cancer (6). Dietary intakes of β-carotene from food and supplements, as well as intakes of lutein and zeaxanthin and vitamin A from foods, were marginally inversely associated with breast cancer risks among premenopausal, but not postmenopausal, women in a previous study in the NHS, and those associations were stronger in women with a family history of breast cancer (13). Due to the controversies arising from previous β-carotene supplementation trials in individuals at high risk of lung cancer (14), the use of specific carotenoid supplements is not advised. However, since most circulating carotenoids come from dietary sources (6, 15), these data suggest promising opportunities to integrate recommendations for diets high in carotenoids into breast cancer prevention for women who are at higher risk.

The objective of this study was to examine whether women at high risk of overall (primary outcome) and ER-specific (secondary outcomes) breast cancer would have greater risk reductions from higher circulating levels of carotenoids. High risk women are defined as women with genetic predispositions or women with higher mammographic densities. In the Breast Cancer Association Consortium (BCAC)—in which the NHS was 1 of the participating cohorts—a 4.37-fold higher risk of developing ER-positive disease was observed when comparing women with the highest 1% of genetic risk to those in the middle quintile (16). Among postmenopausal women in the NHS, the relative risk of breast cancer associated with mammographic density (MD) was 3.8 when comparing the highest vs. lowest quartiles (17).

Methods

Study population

Our study includes participants from the NHS and its second cohort (NHSII), both of which are large-scale, prospective, longitudinal cohorts of registered female nurses in the United States. The NHS was established in 1976, when 121,701 women aged 30–55 years completed and returned an initial questionnaire. In 1989, the NHSII was initiated, which enrolled 116,429 women ages 25–42 years who completed and returned an initial questionnaire. Participants have been followed via questionnaires mailed biennially to update information on exposure variables and to ascertain outcomes (18). The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of the Brigham and Women's Hospital and Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, and those of participating registries as required.

Nested case-control selection

Blood was collected among 32,826 women aged 43–69 years in 1989–1990 in the NHS (19) and among 29,611 women aged 32–54 years in 1996–1999 in the NHSII (20). We conducted a nested case-control study within the sub-cohort of women who provided a blood sample. A detailed description has been provided in the Supplemental Methods.

Carotenoid measurements

Plasma carotenoids were measured at the Micronutrient Analysis Laboratory at the Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health using reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (6). Carotenoids were assayed in 8 batches, and coefficients of variation were, in general, ≤15% (6). Due to technical variations between batches, we recalibrated all batches to an average standard batch, as previously described (6, 20). Statistical outliers (n = 14) were identified and removed using the extreme Studentized deviate many-outlier procedure (20).

Polygenic risk score calculation

Samples from the NHS and NHSII were genotyped using 5 genome-wide association study arrays, including Affymetrix 6.0, IlluminaArray, Illumina OmniExpress, HumanCore, and OncoArray (16). Imputation was performed using 1000 Genomes Project ALL Phase I Integrated Release, Version 3, as the reference panel (21, 22). The effects of cancer susceptibility variants on breast cancer were combined into a polygenic risk score (PRS) for our study participants. A detailed description has been provided in the Supplemental Methods section.

Mammographic density assessment

The craniocaudal views of film mammograms from both breasts were digitized at 261 μm/pixel with a Lumysis 85 laser film scanner (Lymisys) and at 150 dots per inch and 12 bit depth with a VIDAR CAD PRO Advantage scanner (VIDAR Systems Corporation) (23). A detailed description has been provided in the Supplemental Methods.

Covariates

We obtained covariate information from biennial questionnaires [height, age at menarche, parity, age at first birth, family history of breast cancer, personal history of any benign breast disease, alcohol consumption, physical activity, alternative healthy eating index (AHEI) or AHEI-2010], and at blood collection (weight, smoking status). ER status was determined via a central review of breast tissue microarrays or by pathology reports, if tissue was unavailable (24).

Statistical analysis

Among 2780 cases and 2761 controls with prospectively measured circulating carotenoids, 1919 breast cancer cases and 1695 matched controls had complete information on PRS and covariates, while 1344 cases and 1439 controls had complete information on MD and covariates (Supplemental Figure 1). We calculated quartiles of circulating carotenoids and PRS based on distributions of the control population, and used predetermined cutoffs (<10%, 10–24%, 25–49%, ≥50%) for percentage MD. RRs and 95% CIs were calculated using unconditional logistic regressions, adjusting for matching factors and breast cancer risk factors. Tests for trend were conducted using the Wald test, where the medians of the quartiles were modeled continuously. To examine variation in associations by ER status, we evaluated the significance of interaction terms between circulating carotenoids and ER status using Wald tests. To examine whether PRS (or MD) modifies the associations between carotenoids and breast cancer risk on the multiplicative scale, we conducted likelihood ratio tests by comparing 2 generalized linear models with and without the interaction term. Effect modification on the absolute scale was assessed with relative excess risk due to interaction, which measured the difference between the joint RR and the separate contributions by the 2 dichotomized exposures (25). Confidence interval calculations are based on the delta method, as described by Hosmer and Lemeshow (26). Absolute risk reduction (ARR) was calculated based on Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results age-specific incidence rates for White women with invasive breast cancers (2004–2008), the proportion of women in each age strata in the controls, and relative risk estimations, as well as the proportion of controls in each risk strata. CIs for ARR were computed using the delta method (26). All analyses were performed with SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc.) and R 3.4.1 (The R Foundation).

Results

Participant characteristics

The mean ages at blood collection were 53.9 years (SD = 8.3) for cases and 55.1 years (SD = 8.0) for controls (Table 1). At blood draw, 71% of women were post-menopausal. Cases were more likely to have a personal history of benign breast disease (40% vs. 33%) and more likely to have a family history of breast cancer (17% vs. 10%). Participants were predominately White. We observed moderate Spearman correlations between total dietary (food + supplement) intake of carotenoids and circulating levels of carotenoids (α-carotene, ρ = 0.29; β carotene, ρ = 0.23; β cryptoxanthin, ρ = 0.26; lycopene, ρ = 0.13; lutein and zeaxanthin, ρ = 0.26).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of breast cancer cases and matched controls.

| Cases | Controls | |

|---|---|---|

| Variable | N = 1919 | N = 1695 |

| Age at blood draw, years, mean ± SD | 53.9 ± 8.3 | 55.1 ± 8.0 |

| BMI at blood draw, kg/m2, mean ± SD | 25.3 ± 4.6 | 25.2 ± 4.7 |

| Age at menarche, years, mean ± SD | 12.5 ± 1.4 | 12.6 ± 1.4 |

| Age at first birth, years, mean ± SD | 25.7 ± 3.8 | 25.1 ± 3.3 |

| Parity/number of children, mean ± SD | 3.0 ± 1.4 | 3.1 ± 1.5 |

| Postmenopausal, n (%) | 1242 (71%) | 1138 (71%) |

| History of benign breast disease, n (%) | 762 (40%) | 560 (33%) |

| Family history of breast cancer, n (%) | 323 (17%) | 173 (10%) |

| Current smokers, n (%) | 221 (12%) | 169 (10%) |

| Alcohol consumption, gram/day, mean ± SD | 5.1 ± 9.0 | 4.8 ± 8.0 |

| Physical activity, MET-hours/week, mean ± SD | 16.6 ± 20.7 | 17.3 ± 24.7 |

| AHEI index, mean ± SD | 37.3 ± 9.1 | 38.1 ± 9.0 |

| White, n (%) | 1917 (100%) | 1693 (100%) |

| Standardized polygenic risk score, mean ± SD | −0.05 ± 0.62 | −0.38 ± 0.62 |

| Percent mammographic density, median (IQR) | 32.69 (31.50) | 25.85 (28.86) |

| Plasma carotenoids, μg/dL, median (IQR) | ||

| α-carotene | 7.0 (6.8) | 7.3 (7.0) |

| β-carotene | 21.2 (19.5) | 22.7 (21.8) |

| β-cryptoxanthin | 10.4 (7.1) | 10.6 (7.6) |

| Lutein and zeaxanthin | 21.1 (12.5) | 22.0 (13.3) |

| Lycopene | 40.3 (21.8) | 41.5 (22.5) |

| Total carotenoids | 105.2 (53.8) | 109.5 (57.5) |

Data are from blood collections in the NHS and NHSII. Abbreviations: AHEI, alternative healthy eating index; MET, metabolic equivalent of task; NHS, Nurses' Health Study; NHSII, second cohort of the Nurses' Health Study.

Main effects of circulating carotenoids, genetic predisposition, MD, and breast cancer risk

We observed statistically significant inverse associations between circulating concentrations of individual and total carotenoids and the overall breast cancer risk (Table 2; Supplemental Table 1), consistent with our previous studies (6). Women in the highest quartile of total carotenoids had a 20% reduced risk of breast cancer (RR = 0.80; 95% CI, 0.66–0.98; P-trend = 0.006) compared to women in the lowest quartile. A similar magnitude of risk reduction was observed for women in the highest quartiles of α-carotene (RR = 0.80; 95% CI, 0.66–0.98; P-trend = 0.03), β-carotene (RR = 0.82; 95% CI, 0.67–1.00; P-trend = 0.01), lutein and zeaxanthin (RR = 0.83; 95% CI, 0.68–1.01; P-trend = 0.01), and lycopene (RR = 0.85; 95% CI, 0.70–1.03; P-trend = 0.06) relative to women in the lowest quartiles (Supplemental Table 1). The associations between carotenoids and breast cancer risk did not differ by ER status (P for interaction = 0.17) and, in subsequent stratified analyses, RRs were similar for ER-positive and ER-negative diseases for α-carotene, β-carotene, and lycopene (i.e., β-carotene top vs. bottom quartile RRs: 0.82 for ER-positive and 0.80 for ER-negative diseases), although the total number of ER-negative cases were limited (n = 288; Supplemental Table 1). The associations between circulating carotenoids and the breast cancer risk were attenuated slightly when we further adjusted for AHEI, and the associations with β-carotene (P-trend = 0.03), lycopene (P-trend = 0.05), and the total circulating carotenoids (P-trend = 0.02) remained significant even after the adjustment of AHEI (Supplemental Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Multivariable RRs and 95% CIs of breast cancer according to quartiles of plasma carotenoids.

| Q1, <84.6 μg/dL | Q2, 84.6 to <109.5 μg/dL | Q3, 109.5 to <142.1 μg/dL | Q4, ≥142.1 μg/dL | P-trend | P-heterogeneity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall breast cancer | ||||||

| Cases/controls, n | 523/424 | 519/423 | 465/424 | 412/424 | ||

| RR (95% CI) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (0.83–1.21) | 0.89 (0.73–1.08) | 0.80 (0.66–0.98) | 0.006 | 0.17 |

| ER-positive breast cancer | ||||||

| Cases/controls, n | 394/424 | 381/423 | 319/424 | 290/424 | ||

| RR (95% CI) | 1.00 (ref) | 0.96 (0.79–1.17) | 0.80 (0.65–0.98) | 0.73 (0.59–0.91) | 0.008 | |

| ER-negative breast cancer | ||||||

| Cases/controls, n | 69/424 | 77/423 | 79/424 | 63/424 | ||

| RR (95% CI) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.13 (0.79–1.63) | 1.16 (0.81–1.68) | 0.99 (0.67–1.47) | 0.69 | |

Data are from the NHS and NHSII. Models are adjusted for age at blood draw (continuous), BMI at blood draw (continuous), family history (yes vs. no), history of benign breast disease (yes vs. no), alcohol consumption (non-drinker, <5 g/day, 5–10 g/day, 10–15 g/day, or 15+ g/day), age at first birth/parity (nulliparous; 1 or 2 children and <25 years old; 1 or 2 children and 25–29 years old; 1 or 2 children and 30+ years old; 3+ children and <25 years old; or 3+ children and 25+ years old), menopausal status (premenopausal, postmenopausal, or unknown), age at menarche (11 years or younger, 12 years, 13 years, or 14+ years), and smoking status (never, former, or current). RRs and 95% CIs were calculated using unconditional logistic regressions, adjusting for matching factors and breast cancer risk factors; tests for trend were conducted using the Wald test, where the medians of the quartiles were modeled continuously. Abbreviations: ER, estrogen receptor; NHS, Nurses' Health Study; NHSII, second cohort of the Nurses' Health Study.

Both PRS and percentage MD were positively associated with the breast cancer risk in this nested-case control study. Women in the highest quartile of PRS were at a 4-fold increased risk of overall breast cancer compared with women in the lowest quartile (RR = 4.04; 95% CI, 3.29–4.96; P-trend < 0.0001). Similarly, we observed a 3-fold increase in the overall breast cancer risk (RR = 2.95; 95% CI, 2.17–4.03; P-trend < 0.0001) when comparing women with ≥50% MD to those with <10% (Tables 3 and 4). Stratified analyses by ER status showed the magnitude of association between PRS (or MD) and ER-positive disease was comparable to that of overall breast cancer, while for ER-negative disease, a 2.5-fold increase in risk was observed when comparing women in the highest to the lowest PRS quartiles (RR = 2.55; 95% CI, 2.10–3.10; P-trend < 0.0001) and a 4-fold increase in risk was observed when comparing women with ≥50% MD to those with <10% (RR = 4.35; 95% CI, 2.31–8.47; P-trend < 0.0001). We also conducted a secondary analysis categorizing women's risk by combining both PRS and MD categories; women were categorized as high risk [women in the highest 2 quartiles (Q3, Q4) of both PRS and MD], low risk [women in the lowest quartile (Q1) of both PRS and MD], or intermediate risk (women who were not in the highest 2 quartiles of both PRS and MD, and not in the lowest quartiles of both PRS and MD). Compared to women in the lowest-risk group, we observed significantly higher breast cancer risks for those in the intermediate (RR = 3.56; 95% CI, 1.38–11.02) and high-risk groups (RR = 5.31; 95% CI, 1.86–17.69).

TABLE 3.

Multivariable RRs and 95% CIs of breast cancer according to quartiles of polygenic risk score.

| Q1, ←0.8 | Q2, −0.8 to ←0.4 | Q3, −0.4 to <0.03 | Q4, ≥0.03 | P-trend | P-heterogeneity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall breast cancer† | ||||||

| Cases/controls, n | 211/424 | 386/424 | 443/423 | 897/424 | ||

| RR (95% CI) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.80 (1.44–2.23) | 2.01 (1.69–2.61) | 4.04 (3.29–4.96) | <0.0001 | 0.001 |

| ER-positive breast cancer† | ||||||

| Cases/controls, n | 135/424 | 264/424 | 312/423 | 673/424 | ||

| RR (95% CI) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.91 (1.50–2.45) | 2.31 (1.81–2.96) | 4.84 (3.85–6.12) | <0.0001 | |

| ER-negative breast cancer‡ | ||||||

| Cases/controls, n | 48/424 | 64/424 | 65/424 | 111/424 | ||

| RR (95% CI) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.30 (1.06–1.60) | 1.65 (1.35–2.02) | 2.55 (2.10–3.10) | <0.0001 | |

Data are from the NHS and NHSII. Models are adjusted for age at blood draw (continuous), BMI at blood draw (continuous), family history (yes vs. no), history of benign breast disease (yes vs. no), alcohol consumption (non-drinker, <5 g/day, 5–10 g/day, 10–15 g/day, or 15+ g/day), age at first birth/parity (nulliparous; 1 or 2 children and <25 years old; 1 or 2 children and 25–29 years old; 1 or 2 children and 30+ years old; 3+ children and <25 years old; or 3+ children and 25+ years old), menopausal status (premenopausal, postmenopausal, or unknown), age at menarche (11 years or younger, 12 years, 13 years, or 14+ years), and smoking status (never, former, or current). RRs and 95% CIs were calculated using unconditional logistic regressions, adjusting for matching factors and breast cancer risk factors; tests for trend were conducted using the Wald test, where the medians of the quartiles were modeled continuously. †The standardized PRS score for overall and ER-positive breast cancer is based on 313 SNPs with overall and subtype specific weights. ‡The standardized PRS score for ER-negative breast cancer is based on 313 SNPs with subtype specific weights. Abbreviations: ER, estrogen receptor; MD, mammographic density; NHS, Nurses' Health Study; NHSII, second cohort of the Nurses' Health Study; PRS, polygenic risk score.

TABLE 4.

Multivariable RRs and 95% CIs of breast cancer according to predetermined cutoff of mammographic density.

| C1, <10% | C2, 10 to <25% | C3, 25 to <50% | C4, ≥50% | P-trend | P-heterogeneity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall breast cancer | ||||||

| Cases/controls, n | 152/247 | 336/456 | 530/497 | 326/239 | ||

| RR (95% CI) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.33 (1.03–1.72) | 2.14 (1.65–2.79) | 2.95 (2.17–4.03) | <0.0001 | 0.12 |

| ER-positive breast cancer | ||||||

| Cases/controls, n | 114/247 | 239/456 | 357/497 | 222/239 | ||

| RR (95% CI) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.24 (0.94–1.65) | 1.87 (1.40–2.49) | 2.61 (1.86–3.67) | <0.0001 | |

| ER-negative breast cancer | ||||||

| Cases/controls, n | 19/247 | 56/456 | 95/497 | 52/239 | ||

| RR (95% CI) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.93 (1.12–3.48) | 3.42 (1.99–6.17) | 4.35 (2.31–8.47) | <0.0001 | |

Data are from the NHS and NHSII. Models are adjusted for age at blood draw (continuous), BMI at blood draw (continuous), family history (yes vs. no), history of benign breast disease (yes vs. no), alcohol consumption (non-drinker, <5 g/day, 5–10 g/day, 10–15 g/day, or 15+ g/day), age at first birth/parity (nulliparous; 1 or 2 children and <25 years old; 1 or 2 children and 25–29 years old; 1 or 2 children and 30+ years old; 3+ children and <25 years old; or 3+ children and 25+ years old), menopausal status (premenopausal, postmenopausal, or unknown), age at menarche (11 years or younger, 12 years, 13 years, or 14+ years), and smoking status (never, former, or current). RRs and 95% CIs were calculated using unconditional logistic regressions, adjusting for matching factors and breast cancer risk factors; tests for trend were conducted using the Wald test, where the medians of the quartiles were modeled continuously. Abbreviations: ER, estrogen receptor; MD, mammographic density; NHS, Nurses' Health Study; NHSII, second cohort of the Nurses' Health Study; PRS, polygenic risk score.

Circulating carotenoids and breast cancer risk according to genetic predispositions and MD

We did not find evidence that PRS modified the associations between circulating carotenoids and the overall breast cancer risk on the multiplicative scale (P for interaction = 0.93; Figure 1), indicating that RRs between carotenoids and the breast cancer risk did not differ across women with different PRS profiles. However, a statistically significant additive interaction was evident between carotenoids and PRS (P for interaction = 0.05; Figure 1), and we showed a significant ARR in individuals with high PRS, but not women with low PRS (Table 5). Among women in higher quartiles of PRS (Q3 and Q4), 17.1% (95% CI, 2.1–32.8%) and 28.6% (95% CI, 14.8–42.1%) ARRs were observed when comparing women in the highest to the lowest quartile of circulating total carotenoids (Table 5).

FIGURE 1.

Multivariable RRs (95% CI) of overall breast cancer by (A) quartiles of carotenoids and PRS (case n = 1919; control n = 1695) and (B) quartiles of carotenoids and predetermined cutoff of MD (case n = 1439; control n = 1344). Models adjusted for age at blood draw (continuous), BMI at blood draw (continuous), family history (yes vs. no), history of benign breast disease (yes vs. no), alcohol consumption (non-drinker, <5 g/day, 5–10 g/day, 10–15 g/day, or 15+ g/day), age at first birth/parity (nulliparous; 1 or 2 children and <25 years old; 1 or 2 children and 25–29 years old; 1 or 2 children 30+ years old; 3+ children and <25 years old; or 3+ children and 25+ years old), menopausal status (premenopausal, postmenopausal, or unknown), age at menarche (11 years or younger, 12 years, 13 years, or 14+ years), and smoking status (never, former, or current). Multiplicative interaction was tested with a likelihood ratio test through comparing 2 generalized linear models with and without the interaction term. Additive interaction was assessed with relative excess risk due to interaction, which measured the difference between the joint RR and the separate contributions by the 2 dichotomized exposures. Standard error for additive interaction was estimated with the delta method as described by Hosmer and Lemeshow (26). Abbreviations: MD, mammographic density; PRS, polygenic risk score.

TABLE 5.

Percentage of absolute risk reduction of overall breast cancer according to quartiles of circulating carotenoids and polygenic risk score.

| Polygenic risk score | Additive P-interaction | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carotenoids | Q1, ←0.8 | Q2, −0.8 to ←0.4 | Q3, −0.4 to <0.03 | Q4, ≥0.03 | |

| Q1, <84.6 μg/dL | 0 (ref) | 0 (ref) | 0 (ref) | 0 (ref) | |

| Q2, 84.6 to <109.5 μg/dL | 4.2% (−16.9 to 24.9%) | 16.4% (−0.6 to 32.4%) | 9.7% (−6.0 to 26.6%) | 30.3% (18.1–42.8%) | |

| Q3, 109.5 to 142.1 μg/dL | 17.1% (−1.3 to 35.3%) | 2.5% (−16.4 to 21.3%) | 9.6% (−7.2 to 26.2%) | 24.8% (11.6–38.7%) | |

| Q4, ≥142.1 μg/dL | 14.9% (−4.4 to 34.4%) | 13.7% (−3.4 to 31.5%) | 17.1% (2.1–32.8%) | 28.6% (14.8–42.1%) | 0.05 |

Data are from the NHS and NHSII. N cases = 1919; N controls = 1695. ARR was calculated based on Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results age-specific incidence rates for White women with invasive breast cancers (2004–2008), the proportion of women in each age strata in the controls, and relative risk estimations, as well as the proportion of controls in each risk strata. Confidence intervals for ARR were computed using the delta method. Abbreviations: ARR, absolute risk reduction; NHS, Nurses' Health Study; NHSII, second cohort of the Nurses' Health Study.

The inverse association between circulating carotenoids and the overall breast cancer risk was stronger among women with a higher MD than that among those with a lower density, and we observed significant interactions on both the multiplicative and additive scales (multiplicative P for interaction = 0.04; additive P for interaction = 0.05; Figure 1). Among women with higher MDs (≥25%), circulating carotenoids were associated with a 20% reduction in the relative breast cancer risk (top vs. bottom quartile RR = 0.80; 95% CI, 0.67–0.94). However, there was no inverse association between carotenoids and breast cancer risk among women with low MDs (<10%; RR = 1.05; 95% CI, 0.66–1.49). In terms of ARR, a similar pattern was observed. Women with high MDs had significant ARRs as the circulating carotenoids level increased [top- vs. bottom-quartile ARRs were 39.5% for C2 (95% CI, 27.4–51.2%), 63.4% for C3 (95% CI, 55.3–71.1%), and 37.1% for C4 (95% CI, 21.7–52.1%); Table 6]. However, we did not find significant inverse associations between carotenoids and the breast cancer risk for women with low MDs (<10%; P-trend = 0.857). Among high-risk individuals, defined by both PRS and MD, we observed a 64% ARR when comparing the highest to the lowest carotenoid quartiles. However, the main limitation of this analysis is that the small sample size gets smaller when we define high risk based on both PRS and MD, which is reflected in the wide confidence intervals.

TABLE 6.

Percentage of absolute risk reduction of overall breast cancer according to quartiles of carotenoids and predetermined cutoff of mammographic density.

| Percent mammographic density | Additive P-interaction | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carotenoids | C1, <10% | C2, 10 to < 25% | C3, 25 to <50% | C4, ≥50% | |

| Q1, <84.6 μg/dL | 0 (ref) | 0 (ref) | 0 (ref) | 0 (ref) | |

| Q2, 84.6 to <109.5 μg/dL | −22.7% (−50.2 to 4.7%) | 28.4% (14.4–41.8%) | 60.4% (51.6–69.3%) | 52.5% (41.1–63.6%) | |

| Q3, 109.5 to 142.1 μg/dL | 12.2% (−7.5 to 31.9%) | 5.9% (−12.4 to 23.6%) | 42.5% (30.4–54.9%) | 28.8% (11.7–45.4%) | |

| Q4, ≥142.1 μg/dL | −6.4% (−30.9 to 18.1%) | 39.5% (27.4–51.2%) | 63.1% (55.3–71.1%) | 37.1% (21.7–52.1%) | 0.05 |

Data are from the NHS and NHSII. N case = 1439; N control = 1344. ARR was calculated based on Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results age-specific incidence rates for White women with invasive breast cancers (2004–2008), the proportion of women in each age strata in the controls, and relative risk estimations, as well as the proportion of controls in each risk strata. Confidence intervals for ARR were computed using the delta method. Abbreviations: ARR, absolute risk reduction; NHS, Nurses' Health Study; NHSII, second cohort of the Nurses' Health Study.

Discussion

In this large, nested case-control study, we showed that when compared with women at a low genetic risk, those with higher genetic risk scores had greater ARRs for breast cancer with higher circulating carotenoid levels. Similarly, with elevated levels of circulating carotenoids, women with high MDs also showed more pronounced relative and absolute risk reductions. Notably, among women in the high-risk categories (i.e., high PRS or high MD), there was an approximately 30–60% ARR for breast cancer when comparing higher quartiles to the lowest quartiles of carotenoid levels. However, high carotenoid levels were not associated with an ARR among women with low PRS or low MD. Measuring risk on the relative and absolute scales usually conveys different information. Given the same risk ratio, a more substantial risk difference may be present comparing women with high (i.e., in the high PRS strata) vs. low (i.e., in the low PRS strata) baseline risk. The ARR may present a more relevant measure for women at high risk.

Accumulating epidemiological evidence has linked dietary and circulating carotenoids with a reduced risk of breast cancer (2–5, 9–12). Pooled analyses from multiple prospective cohorts showed that higher circulating levels of carotenoid are associated with a reduced breast cancer risk (6, 11). In the NHS cohorts, total plasma carotenoid concentrations measured ≥10 years before diagnosis were significantly associated with lower risks of breast cancer (RR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.63–0.94) (6). Dietary intakes of β-carotene from food and supplements, as well as intakes of lutein and zeaxanthin and vitamin A from foods, were marginally inversely associated with breast cancer risks among premenopausal women in the NHS, and those associations were stronger in women with a family history of breast cancer (13). Consistent with previous findings, we showed inverse associations between circulating concentrations of individual and total carotenoids and the breast cancer risk. However, due to a limited number of cases, we did not find evidence of an association between carotenoids and an ER-negative breast cancer risk.

Women with genetic predispositions or high MDs are at greater risk of developing breast cancer. Including PRS and MD has significantly improved breast cancer risk prediction models in the NHS (27). Using the same PRS, analyses within BCAC showed that compared with women in the middle quintile, those in the highest 1% of risk had 4- and 3-fold increased risks of developing ER-positive and ER-negative breast cancer, respectively (16). The current analyses expanded on these findings by testing multiplicative interactions between carotenoids and PRS. However, we did not observe significant multiplicative interactions, suggesting that RRs between carotenoids and the breast cancer risk did not differ across PRS strata. Importantly, this implies that carotenoids are associated with a lower risk of breast cancer regardless of the underlying risk due to genetics or MD. Previous studies have also shown that women with dense breast tissue in ≥75% of the breast have 4–6 times the risk of developing breast cancer than women with little or no dense tissue (28–32). Among 604 cases and 626 controls, our previous work showed that individual and total carotenoids were associated with 40–50% reductions in RR for women in the highest tertiles of MD (10). Our current study, with up to 3 times the sample size, yielded very similar results, indicating that circulating carotenoids may play a role in reducing breast cancer risk, especially for women with high MDs. Additionally, we for the first time evaluated the interaction on the absolute scale. Our study showed that when compared with women with a low genetic risk or low MD, those with a higher PRS or MD yielded a greater ARR for breast cancer as the circulating carotenoid level increased. We demonstrated significant ARRs among women with high PRSs or MDs, but not for women with low PRSs or MDs.

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network of the National Cancer Institute recommends women who have 2 or more first- to third-degree relatives with breast cancer on the same side of the family to consider population genetic testing at an age of ≤50 years (33). Although PRSs are not currently assessed in the clinic, advances in precision medicine initiatives may aid in the scaling-up of genome-wide detection of germline genetic mutations to the general public, which will enable a more comprehensive evaluation of a woman's genetic risk profile. However, for those with a strong family history, mutation panels should be used, which include high penetrance breast cancer variants such as BRCA1 and BRCA2. Mammographic screening starting at age 45 years for women with an average risk of breast cancer is strongly recommended by the American Cancer Society. To date, 36 states in the United States require health-care provider reporting of women with dense breasts (34). Although breast imaging reporting and data system (BI-RADS) density measurements are used in the clinic, the percentage density measure used in this study is highly correlated with BI-RADS density (35) and has better measurement reliability. There are some clinics that are incorporating continuous and automated measures of breast density. For example, VolparaDensity is cleared by the FDA to provide both volumetric breast density measurements and a breast density category, which has been shown to correlate to BI-RADS 4th and 5th Edition density categories and is easy to implement clinically (36–38); although not widespread, this represents a future opportunity for clinical translation. Therefore, we believe that PRS and MD are important risk assessment tools to use in characterizing those women at high risk of developing breast cancer. Our study suggests that future work should evaluate integrating risk stratification with personal-level interventions to reduce risks of breast cancer, which would be particularly valuable for high-risk individuals who could benefit from less invasive preventive options.

In the NHS, we have previously assessed carotenoid-contributing food items for individual circulating carotenoid levels (39). Among food items assessed with a validated FFQ, we showed that carrots (raw and cooked), broccoli, and romaine or leaf lettuce are significant food contributors for α-and-β-carotenes; oranges and orange juice are contributors for β-cryptoxanthin; romaine or leaf lettuce, orange juice, and broccoli are contributors for lutein and zeaxanthin; and tomato sauce, tomatoes, and tomato juice are contributors for lycopene (40). Since carotenoids are available in a wide range of common food items, our findings suggest benefits of a diet high in carotenoid-rich fruit and vegetables for primary breast cancer prevention, particularly for those at high risk.

Our study has several strengths. To our knowledge, this study is the first to report, on the absolute scale, the potential beneficial effects of carotenoids on the breast cancer risk among high-risk individuals. Our findings suggest that ARR is a clinically more meaningful measure, particularly for designing tailored personalized prevention for high-risk populations. Since the majority of circulating carotenoids come from dietary sources (6, 15) (i.e., carrots for α-carotene and β-carotene, citrus fruits for β-cryptoxanthin, tomatoes for lycopene, and leafy greens for lutein and zeaxanthin), consuming a diet high in carotenoid-rich fruits and vegetables may represent a cost-effective method of breast cancer prevention, which could be easily integrated into daily life. Our study also has a number of limitations. Circulating carotenoids were measured at a single time point in this analysis; although the reproducibility over a 2–3-year period in the NHS is relatively high [intraclass correlation (ICC), 0.73–0.88] (40), the 10-year reproducibility was attenuated (ICC, 0.39–0.54) (6). Our sample size for ER-negative disease was small, which limited our power to detect significant associations; further pooled analyses are warranted to study rarer breast cancer molecular subtypes. Our findings may not be generalizable to other ethnic groups, as study participants in the NHS and this nested case-control study were predominantly White; future work with more diverse populations is needed to verify our findings in other racial/ethnic groups. Although a large-scale pooled analysis suggests that circulating levels of carotenoids are associated with a lowered breast cancer risk (2), findings for the associations between diets high in carotenoid-containing foods and the breast cancer risk are less conclusive (3, 4, 13, 41, 42). In the NHS, we previously reported marginal associations between cumulative fruit and vegetable consumption and reduced breast cancer risks among premenopausal women (RR = 0.77; 95% CI, 0.58–1.02), but not postmenopausal women (RR = 1.03; 95% CI, 0.81–1.31) (13). Dietary and supplement β-carotene intake, as well as lutein and zeaxanthin intake, were also inversely associated with the breast cancer risk in the NHS (13). In the Women's Health Initiative, dietary α-carotene, β-carotene, and lycopene were inversely associated with ER-positive/progesterone receptor-positive breast cancer risks (5). Several other prospective studies have reported null associations for dietary carotenoids intake and breast cancer risk (4, 41, 42). This lack of consistency may represent differences in the absorption and downstream bioavailability of carotenoids, or may indicate that circulating carotenoids are a biomarker for a high-quality diet or an active lifestyle. Because of the controversies arising from previous β-carotene supplementation trials in individuals at high risk of lung cancer (14), it is imperative that we have a firm understanding of the mechanisms by which carotenoids modulate biological pathways before we can make nutrient-specific recommendations.

In conclusion, in this large, nested case-control study, we showed that women with a high genetic risk or high MD demonstrated the largest numerical ARR as carotenoid levels increased from the lowest to the higher quartiles. Since fruit and vegetables represent a major source of naturally occurring carotenoids, our findings support the need to test dietary fruit and vegetable interventions that increase circulating levels of carotenoids as a means of reducing the breast cancer risk, especially for those individuals at high risk.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the cancer registries in the following states for their help with providing information for confirming cancer self-reports in participants: AL, AR, AZ, CA, CO, CT, DE, FL, GA, IA, ID, IL, IN, KY, LA, MA, MD, ME, MI, NC, ND, NE, NH, NJ, NY, OH, OK, OR, PA, RI, SC, TN, TX, VA, WA, and WY.

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows —CP, BR, SEH, PK, AHE, and RMT: designed the research; CP, CG, DL, BR, OZ, PK, AHE, and RMT: conducted the research; CP and CG: performed statistical analyses; and all authors: wrote the manuscript and read and approved the final manuscript.

Author disclosures: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Notes

This study was funded by the Prevent Cancer Foundation (analysis and interpretation of results), the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute (UM1 CA186107, P01 CA87969, R01 CA49449, U01 CA176726, R01 CA67262, R01 CA50385, U19 CA148065), and a National Institute of Health Epidemiology Education Training Grant (T32 CA09001).

The authors assume full responsibility for analyses and interpretation of these data.

Supplemental Methods, Supplemental Tables 1 and 2, and Supplemental Figure 1 are available from the “Supplementary data” link in the online posting of the article and from the same link in the online table of contents at https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/.

AHE and RMT contributed equally to this work and are joint senior authors.

Data Availability: Data described in the manuscript, code book, and analytic code will be made available upon application and approval.

Abbreviations used: AHEI, alternative healthy eating index; ARR, absolute risk reduction; BCAC, Breast Cancer Association Consortium; BI-RADS, breast imaging reporting and data system; ER, estrogen receptor; ICC, intraclass correlation; MD, mammographic density; NHS, Nurses’ Health Study; NHSII, second cohort of the Nurses' Health Study; PRS, polygenic risk score.

Contributor Information

Cheng Peng, Channing Division of Network Medicine, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, MA, USA.

Chi Gao, Department of Epidemiology, Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA.

Donghao Lu, Channing Division of Network Medicine, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, MA, USA; Department of Medical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden.

Bernard A Rosner, Channing Division of Network Medicine, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, MA, USA; Department of Biostatistics, Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA.

Oana Zeleznik, Channing Division of Network Medicine, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, MA, USA.

Susan E Hankinson, Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, School of Public Health and Health Sciences, University of Massachusetts Amherst, Amherst, MA, USA.

Peter Kraft, Department of Epidemiology, Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA; Department of Biostatistics, Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA.

A Heather Eliassen, Channing Division of Network Medicine, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, MA, USA; Department of Epidemiology, Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA.

Rulla M Tamimi, Department of Epidemiology, Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA; Department of Population Health Sciences, Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, NY, USA.

References

- 1. Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Eliassen AH, Hendrickson SJ, Brinton LA, Buring JE, Campos H, Dai Q, Dorgan JF, Franke AA, Gao YT, Goodman MTet al. Circulating carotenoids and risk of breast cancer: Pooled analysis of eight prospective studies. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104(24):1905–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhang X, Spiegelman D, Baglietto L, Bernstein L, Boggs DA, van den Brandt PA, Buring JE, Gapstur SM, Giles GG, Giovannucci Eet al. Carotenoid intakes and risk of breast cancer defined by estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor status: A pooled analysis of 18 prospective cohort studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95(3):713–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Larsson SC, Bergkvist L, Wolk A. Dietary carotenoids and risk of hormone receptor-defined breast cancer in a prospective cohort of Swedish women. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46(6):1079–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cui Y, Shikany JM, Liu S, Shagufta Y, Rohan TE. Selected antioxidants and risk of hormone receptor-defined invasive breast cancers among postmenopausal women in the Women's Health Initiative Observational Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87(4):1009–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Eliassen AH, Liao X, Rosner B, Tamimi RM, Tworoger SS, Hankinson SE. Plasma carotenoids and risk of breast cancer over 20 y of follow-up. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;101(6):1197–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Al Tanoury Z, Piskunov A, Rochette-Egly C. Vitamin A and retinoid signaling: Genomic and nongenomic effects. J Lipid Res. 2013;54(7):1761–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tibaduiza EC, Fleet JC, Russell RM, Krinsky NI. Excentric cleavage products of beta-carotene inhibit estrogen receptor positive and negative breast tumor cell growth in vitro and inhibit activator protein-1-mediated transcriptional activation. J Nutr. 2002;132(6):1368–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tamimi RM, Hankinson SE, Campos H, Spiegelman D, Zhang S, Colditz GA, Willett WC, Hunter DJ. Plasma carotenoids, retinol, and tocopherols and risk of breast cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;161(2):153–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tamimi RM, Colditz GA, Hankinson SE. Circulating carotenoids, mammographic density, and subsequent risk of breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2009;69(24):9323–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Aune D, Chan DS, Vieira AR, Navarro Rosenblatt DA, Vieira R, Greenwood DC, Norat T. Dietary compared with blood concentrations of carotenoids and breast cancer risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;96(2):356–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hu F, Wang Yi B, Zhang W, Liang J, Lin C, Li D, Wang F, Pang D, Zhao Y. Carotenoids and breast cancer risk: A meta-analysis and meta-regression. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;131(1):239–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhang S, Hunter DJ, Forman MR, Rosner BA, Speizer FE, Colditz GA, Manson JE, Hankinson SE, Willett WC. Dietary carotenoids and vitamins A, C, and E and risk of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91(6):547–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Omenn GS, Goodman GE, Thornquist MD, Balmes J, Cullen MR, Glass A, Keogh JP, Meyskens FL, Valanis B, Williams JHet al. Effects of a combination of beta carotene and vitamin A on lung cancer and cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(18):1150–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Motchnik PA, Frei B, Ames BN. Measurement of antioxidants in human blood plasma. Methods Enzymol. 1994;234:269–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mavaddat N, Michailidou K, Dennis J, Lush M, Fachal L, Lee A, Tyrer JP, Chen TH, Wang Q, Bolla MKet al. Polygenic risk scores for prediction of breast cancer and breast cancer subtypes. Am J Hum Genet. 2019;104(1):21–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tamimi RM, Byrne C, Colditz GA, Hankinson SE. Endogenous hormone levels, mammographic density, and subsequent risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99(15):1178–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Eliassen AH, Colditz GA, Rosner B, Willett WC, Hankinson SE. Adult weight change and risk of postmenopausal breast cancer. JAMA. 2006;296(2):193–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hankinson SE, Willett WC, Manson JE, Hunter DJ, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Longcope C, Speizer FE. Alcohol, height, and adiposity in relation to estrogen and prolactin levels in postmenopausal women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87(17):1297–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sisti JS, Lindstrom S, Kraft P, Tamimi RM, Rosner BA, Wu T, Willett WC, Eliassen AH. Premenopausal plasma carotenoids, fluorescent oxidation products, and subsequent breast cancer risk in the Nurses' Health Studies. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;151(2):415–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Michailidou K, Lindstrom S, Dennis J, Beesley J, Hui S, Kar S, Lemacon A, Soucy P, Glubb D, Rostamianfar Aet al. Association analysis identifies 65 new breast cancer risk loci. Nature. 2017;551(7678):92–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Michailidou K, Hall P, Gonzalez-Neira A, Ghoussaini M, Dennis J, Milne RL, Schmidt MK, Chang-Claude J, Bojesen SE, Bolla MKet al. Large-scale genotyping identifies 41 new loci associated with breast cancer risk. Nat Genet. 2013;45(4):353–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rice MS, Bertrand KA, VanderWeele TJ, Rosner BA, Liao X, Adami HO, Tamimi RM. Mammographic density and breast cancer risk: A mediation analysis. Breast Cancer Res. 2016;18(1):94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tamimi RM, Baer HJ, Marotti J, Galan M, Galaburda L, Fu Y, Deitz AC, Connolly JL, Schnitt SJ, Colditz GAet al. Comparison of molecular phenotypes of ductal carcinoma in situ and invasive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2008;10(4):R67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Knol MJ, VanderWeele TJ, Groenwold RH, Klungel OH, Rovers MM, Grobbee DE. Estimating measures of interaction on an additive scale for preventive exposures. Eur J Epidemiol. 2011;26(6):433–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Confidence interval estimation of interaction. Epidemiology. 1992;3(5):452–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhang X, Rice M, Tworoger SS, Rosner BA, Eliassen AH, Tamimi RM, Joshi AD, Lindstrom S, Qian J, Colditz GAet al. Addition of a polygenic risk score, mammographic density, and endogenous hormones to existing breast cancer risk prediction models: A nested case-control study. PLOS Med. 2018;15(9):e1002644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ursin G, Ma H, Wu AH, Bernstein L, Salane M, Parisky YR, Astrahan M, Siozon CC, Pike MC. Mammographic density and breast cancer in three ethnic groups. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12(4):332–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Byrne C, Schairer C, Wolfe J, Parekh N, Salane M, Brinton LA, Hoover R, Haile R. Mammographic features and breast cancer risk: Effects with time, age, and menopause status. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87(21):1622–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Boyd NF, Byng JW, Jong RA, Fishell EK, Little LE, Miller AB, Lockwood GA, Tritchler DL, Yaffe MJ. Quantitative classification of mammographic densities and breast cancer risk: Results from the Canadian National Breast Screening Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87(9):670–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Boyd NF, Rommens JM, Vogt K, Lee V, Hopper JL, Yaffe MJ, Paterson AD. Mammographic breast density as an intermediate phenotype for breast cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6(10):798–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. McCormack VA, dos Santos Silva I. Breast density and parenchymal patterns as markers of breast cancer risk: A meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(6):1159–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Foulkes WD, Knoppers BM, Turnbull C. Population genetic testing for cancer susceptibility: Founder mutations to genomes. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2016;13(1):41–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dehkordy SF, Carlos RC. Dense breast legislation in the United States: State of the states. J Am Coll Radiol. 2013;10(12):899–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Winkler NS, Raza S, Mackesy M, Birdwell RL. Breast density: Clinical implications and assessment methods. Radiographics. 2015;35(2):316–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Boyd NF, Guo H, Martin LJ, Sun L, Stone J, Fishell E, Jong RA, Hislop G, Chiarelli A, Minkin Set al. Mammographic density and the risk and detection of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(3):227–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Carney PA, Miglioretti DL, Yankaskas BC, Kerlikowske K, Rosenberg R, Rutter CM, Geller BM, Abraham LA, Taplin SH, Dignan Met al. Individual and combined effects of age, breast density, and hormone replacement therapy use on the accuracy of screening mammography. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):168–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Irshad A, Leddy R, Ackerman S, Cluver A, Pavic D, Abid A, Lewis MC. Effects of changes in BI-RADS density assessment guidelines (fourth versus fifth edition) on breast density assessment: Intra- and interreader agreements and density distribution. Am J Roentgenol. 2016;207(6):1366–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hendrickson SJ, Willett WC, Rosner BA, Eliassen AH. Food predictors of plasma carotenoids. Nutrients. 2013;5(10):4051–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kotsopoulos J, Tworoger SS, Campos H, Chung FL, Clevenger CV, Franke AA, Mantzoros CS, Ricchiuti V, Willett WC, Hankinson SEet al. Reproducibility of plasma and urine biomarkers among premenopausal and postmenopausal women from the Nurses' Health Studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19(4):938–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Nagel G, Linseisen J, van Gils CH, Peeters PH, Boutron-Ruault MC, Clavel-Chapelon F, Romieu I, Tjonneland A, Olsen A, Roswall Net al. Dietary beta-carotene, vitamin C and E intake and breast cancer risk in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC). Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;119(3):753–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Michels KB, Holmberg L, Bergkvist L, Ljung H, Bruce A, Wolk A. Dietary antioxidant vitamins, retinol, and breast cancer incidence in a cohort of Swedish women. Int J Cancer. 2001;91(4):563–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.