Abstract

In this work, we developed an experimental‐computational analysis framework which facilitated objective, quantitative, standardised, methodological, and systematic comparisons between the biomechanical efficacies of two fundamentally different dressing technologies for pressure ulcer prevention: A dressing technology based on cellulose fibres used as the core matrix was evaluated vs the conventional silicone‐foam dressing design concept, which was represented by multiple products which belong in this category. Using an anatomically‐realistic computer (finite element) model of a supine female patient to whom the different sacral dressings have been applied virtually, we quantitatively evaluated the efficacy of the different dressings by means of a set of 3 biomechanical indices: The protective efficacy index, the protective endurance, and the prophylactic trade‐off design parameter. Prior rigorous experimental measurements of the physical and mechanical behaviours and properties of each tested dressing, including tensile, compressive, and friction properties, have been conducted and used as inputs for the computer modelling. Each dressing was evaluated for its tissue protection performances at a new (from the package) state, as well as after exposure to moisture conditions simulating wet bedsheets. Our results demonstrated that the dressing with the fluff core is at least as‐good as silicone‐foams but importantly, provides the best balance between protective performances at its “new” condition and the performance after being exposed to moisture. We conclude that preventative dressings are not equal in their prophylactic performances, but rather, the base technology, the ingredients, and their arrangement in the dressing structure shape the quality of the delivered tissue protection.

Keywords: finite element model, moisture, pressure injury, pressure ulcer, prevention

1. INTRODUCTION

A pressure ulcer (PU), also known as a pressure injury, can be painful, may diminish the quality of life of affected individuals and their family members, and is known to increase the hospital length of stay. The annual expense on treating PUs exceeds $26.8 billion in just the United States alone, 1 without considering the substantial penalty sanctions applied by regulators upon excessive occurrence of PUs, the costs of litigation, and the damages instructed or settlement agreements in courts. Governments, health maintenance organisations, hospital managements, insurance companies, and trial juries tend to consider PUs to be largely preventable and thereby, often regard a hospital‐acquired PU as an adverse event. In all the above aspects, pressure ulcer prevention (PUP) strategies are critically important, particularly from a patient safety perspective, healthcare quality ratings, cost‐effectiveness of the delivered healthcare services, and legal liability.

The tissue injury spiral in a forming PU progresses from deformation‐inflicted cell damage to localised inflammatory damage and eventually, to development of ischemic damage. All of these grow and escalate over time and have a cumulative impact on tissue viability, as reviewed in the Aetiology Chapter of the newly released International Clinical Practice Guideline on Pressure Ulcer Prevention & Treatment 2 and the International Consensus Document on Prevention & Treatment of Device‐related Pressure Ulcers. 3 The timeframe for development of a clinically significant tissue damage is relatively short, between tens‐of‐minutes to a couple of hours, but the injury does not emerge instantaneously (as acute tissue damage does). Rather, PUs develop from the cell scale to the tissue scale until presenting themselves on the skin or causing skin and underlying tissue breakdown. 2 , 3 This implies that a gradual and exacerbating tissue damage cascade occurs and most importantly, in the context of the present work, the tissue damage spiral in PUs is triggered and then driven by soft tissue exposure to sustained mechanical deformations and distortions. 2 , 3 Accordingly, alleviating the exposure to sustained skin and deeper soft tissue deformations is the most effective approach for PUP. 2 , 3 Prophylactic dressings are specifically aimed at providing that alleviation of sustained soft tissue loads, at body regions which are known to be at‐risk for PUs, such as the sacrum and heels of patients who are positioned supine in bed.

Use of advanced dressings to protect anatomical sites which are known to be vulnerable to PUs such as the sacrum and heels is relatively new; relevant literature is dated from 2012 onwards and the number of peer‐reviewed journal publications focusing on this topic appears to double every 3 years since. A recently published meta‐analysis of the clinical research reported in the peer‐reviewed literature 4 concluded that prophylactic sacral dressings are effective in PUP, indicating that this intervention decreases the relative PU risk by 70%. Sub‐group analysis of patient data from intensive care units (ICUs) demonstrated an even larger relative risk reduction of 83%, suggesting that sacral dressings may be more protective in this high‐risk group. 4 The latest large randomised clinical trial in prophylactic dressings, conducted in Germany and published after the Fulbrook 4 paper appeared, confirmed the above findings. 5 The latter work included 212 ICU patients in the intervention group (where dressings were applied to the sacrum and heels) and 210 other ICU patients in a control group (mean age of 63.5 years; the majority of patients, 65.4%, were males). The cumulative PU incidence of category‐2 wounds and more severe ones was 2.8% in the intervention group, statistically significantly lower than the corresponding incidence of 10.5% in the control group. Accordingly, at this time, there appears to be a consensus in the literature that the application of dressings to the sacrum and heels, in addition to standard PUP measures such as repositioning and skin inspections, reduces the relative and absolute risks for the development of PUs.

Consistent with the above, the most recent version of the International Clinical Practice Guideline on Pressure Ulcer Prevention & Treatment 6 recommends to “use a soft silicone multi‐layered foam dressing to protect the skin for individuals at risk of pressure injuries (strength of evidence: B1)”. Use of prophylactic dressings for PUP is indeed clinically feasible in ICUs and operating rooms, however, there is large diversity in commercially available dressings for which manufacturers make PUP claims. The costs of these various dressings also differ considerably and so, clinicians are left to decide which specific dressings they should order for their patients. In this regard, the meta‐analysis of Fulbrook et al 4 pointed to the fact that “additional research is needed to clarify the dressing choice”. The choice of a prophylactic dressing should be determined by the biomechanical efficacy of that dressing in alleviate soft tissue loads, both at the skin surface and at deeper tissue layers. Likewise, this decision‐process should also consider the capacity of the dressing of interest to maintain its aforementioned biomechanical performances over the intended time of use, which can range between facilities and care settings (typically it is between 3 and 7 days. 5 , 7 , 8

The emerging field of prophylactic use of dressings is currently dominated by silicone‐foam dressings which are composed of layers of different foams and silicone in a sandwich‐like structure. Of note is that products in the silicone‐foam category differ considerably in their shapes, thicknesses, and the thicknesses of the individual constituent layers, as well as in the specific types of foam materials used in each layer and their mechanical properties. As a result, the structural behaviours of dressings as a whole, for example, their tensile, bending, and compressive behaviours (of the sandwich‐like dressing structure) and the associated dressing stiffness properties differ significantly across silicone‐foam products made by different manufactures. 9 In other words, the geometrical shape, structure, and material composition of a dressing form its biomechanical function and, therefore, a change in the dressing ingredients will inherently result in altered dressing performances. A common false premise is that all silicone‐foam dressings are performing equivalently; published laboratory bioengineering work proves otherwise. 2 , 7 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 Accordingly, it is almost axiomatic that the biomechanical protective effects of a new dressing, having an essentially different structure and composition with respect to the silicone‐foam sandwich concept, cannot be extrapolated from the known silicone‐foam studies and should be studied separately.

In this paper, we developed an experimental‐computational analysis framework which facilitated objective, quantitative, standardised, methodological, and systematic comparisons between the biomechanical efficacies of two fundamentally different dressing technologies for PUP: A new PUP dressing technology based on cellulose fibres used as the core matrix was evaluated vs the conventional silicone‐foam dressing design concept, which was represented in this work by multiple products which belong in this category. Using a computer model of a supine female patient to whom the different sacral dressings have been applied virtually, based on prior rigorous experimental measurements of the physical and mechanical behaviours and properties of each tested dressing, we quantitatively evaluated the efficacy of the different dressings. Each dressing was evaluated for its tissue protection performances at a new (from the package) state, as well as after exposure to moisture conditions simulating wet bedsheets. Our results reported here demonstrate that preventative dressings are not equal in their prophylactic performances, but rather, the base technology, the ingredients and their arrangement in the dressing structure shape the quality of the delivered tissue protection.

2. METHODS

To enable a methodological and systematic quantitative comparison of the biomechanical performances of different sacral dressings in prophylactic use, the finite element (FE) method has been employed here. Based on the methodology in our published research, the influence of the different dressing shapes, material compositions and stiffnesses of the individual dressing layers, as well as the potential impact of humidity (resulting from wet bedsheets, eg, due to incontinence) on the stiffness and friction properties of the dressings under investigation have all been considered in the present modelling work. 10 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 Likewise, the effects of anisotropy of the applied dressings (where relevant) and the stiffness properties of the mattress in interaction with the body of the user and each specific dressing structure, were also incorporated, based on our published FE methodology. 13 , 19 , 20

2.1. Geometry

The anatomically‐realistic, three‐dimensional (3D) model of the buttocks which has been developed for this study is shown in Figure 1. The model reconstructed the detailed 3D surface shapes and volumes of the hard and soft tissue structures which are relevant for evaluating the biomechanical efficacy of sacral prophylactic dressings, that is, bone, skeletal muscle, that is, pose tissues, and skin. The modelling shown in Figure 1 facilitated calculations of surface and internal tissue loads without a dressing and likewise, with each type of an applied prophylactic sacral dressing in dry and moist conditions.

FIGURE 1.

The anatomically‐realistic finite element (FE) computational modelling of the buttocks, based on the MRI‐acquired female subject anatomy: A, The skeleton of the pelvis including the details of the sacral region from a posterior view. B, The relevant skeletal muscle structures added onto the skeleton. C, Adipose and skin tissues added to form the complete anatomical reconstruction, including the hard and soft tissue details. D, The latter geometrical model meshed into elements for the FE modelling process, with a magnified region to show details of the meshing grid

In order to develop the above anatomically‐detailed 3D FE model (Figure 1), we used an already available MRI scan dataset of the buttocks of a supine healthy, young‐old (60‐69 years; definition in Reference 21 female. The body and anthropometric characteristics of the scanned person were as follows: Age 65 years, bodyweight 73.5 kg, height 168 cm, buttocks circumference 101 cm, distance between the ischial tuberosities (ITs) 11 cm, sacral slope 1 66°, sacral inclination 2 24°, coccyx curvature radius in the frontal/sagittal planes 5/5.4 cm, gluteal muscle thickness under the ITs 5.4 cm (contralateral mean for the two ITs), and adipose thickness under the ITs/coccyx 3.1/2.2 cm. The MR image acquisition was performed when the subject was positioned supine, in an open MRI configuration, double donut 3 Tesla MRI system (Siemens Corp., Munich, Germany) utilising T1‐weighted images (TR/TE = 2560/10, field of view 0.8047 mm, slice thickness 3.9 mm). No contrast agents were used.

In order to calculate the state of soft tissue deformations and the resulting distributions of strains and stresses in the soft tissues, an undeformed buttocks model was required, as a reference configuration. 22 , 23 Thus, a custom‐made support surface, made entirely of non‐magnetic materials was used to off‐load the buttocks during the above MRI scan, following the scan acquisition method described in Shoham et al. 24 To validate the calculated FE modelling data, a second MRI image set of the same person was acquired on a standard medical foam mattress to obtain the weight‐bearing state (ie, the deformed configuration) of the soft tissues in the buttocks for the supine posture.

Next, the undeformed (reference configuration) scan set which consisted of 70 slices was transferred to a 3D segmentation software (Simpleware, Synopsys, San José) to segment the hard and soft tissue types considered in the present modelling (bone, muscle, adipose, and skin). After this segmentation, and in order to eliminate potential boundary effects in the specific areas of interest (ie, under the sacrum and near the site of dressing application), the model was extruded by 8 cm along the direction of the spine (this extrusion is depicted in Figure 1A,B where the superior aspects of the skeleton and muscle are extruded). A 10 cm‐thick foam mattress was further added under the buttocks model.

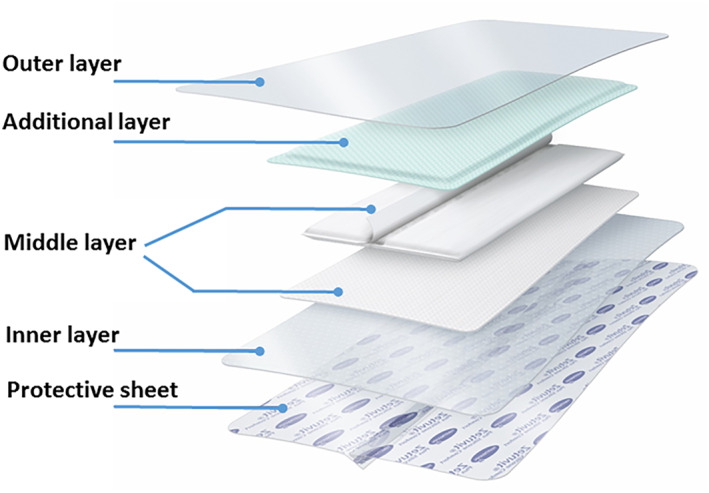

Finally, the geometries of the different dressing products were incorporated in the modelling, each in a separate model variant for a corresponding FE analysis, after measuring the 3D dressing dimensions and the thicknesses of their layered components where relevant. The dressing products studied here were four different multi‐layered silicone‐foam dressing types vs a different dressing technology: the Resposorb Silicone Border (RSB) dressing (Figure 2), also known as Zetuvit Plus Silicone Border (manufactured by Paul Hartmann AG, Heidenheim, Germany). The latter dressing is inherently different from the silicone‐foam dressing family in its structure and composition as instead of a core foam structure, it contains soft cellulose fluff blended with a fluid‐retaining super‐absorber that are enclosed in a non‐woven envelop.

FIGURE 2.

The multi‐layered structure of the Resposorb silicone border dressing. The mechanical properties of the marked layers (excluding the “protective sheet” which is not an integral part of the dressing structure) are reported in Table 2

2.2. Constitutive laws and material parameters of the model components

The constitutive laws and material parameters of all tissue types were adopted from the work of Levy et al. 25 Specifically, bone tissues were assumed to be homogenous, isotropic, and linear elastic with an elastic modulus of 7 GPa and a Poisson's ratio of 0.3. All soft tissues were also considered homogenous and isotropic, however, their non‐linear elastic behaviours under the large tissue deformations imposed by the bodyweight forces have been considered. The soft tissue materials were hence defined to behave according to a hyperelastic Neo‐Hookean constitutive law with tissue‐specific parameters that are listed in Table 1. The viscoelasticity of soft tissues was not considered as all the present FE model variants were used to simulate long times of immobility in a supine position, that is, in the order of hours, whereas the transient viscoelastic phenomena in soft tissues are known to plateau within minutes. 26 , 27 Accordingly, the instantaneous tissue and dressing stiffness properties were considered here, thereby describing the conservative (worst‐case) scenario of soft tissue exposure to internal stresses, per each dressing case, as no tissue stress relaxation was accounted for. 13 , 22 , 23 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29

TABLE 1.

The material parameters associated with a Neo‐Hookean constitutive law for the soft tissues incorporated in the present modelling

| Tissue type | Instantaneous shear modulus (kPa) | Bulk modulus (kPa) | Poisson's ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Skin | 31.900 | 3179.370 | 0.495 |

| Adipose | 0.286 | 28.500 | 0.495 |

| Skeletal muscle | 7.100 | 707.600 | 0.495 |

Note: Values of the tissue material parameters were adopted from Reference 25.

The dressing materials were defined as linear elastic in the respective FE model variants, based on rigorous laboratory testing. In preparation for the testing procedure, each dressing product was carefully disassembled into its structural layers and dog‐bone‐shaped test specimens were then cut from each separated layer. From each of the 2 to 4 layers consisting each product (depending on the product type), 48 specimens were produced for material tests that were conducted according to the DIN EN ISO 527‐2:2012‐06 (German Institute for Standardisation, DIN) testing standard. Where a product or a layer of a product have been considered anisotropic, either because the instructions for use provided by the corresponding manufacturer indicated a specific orientation in which the dressing should be applied, or where the dressing product shape implies application with a specific directionality, additional testing was conducted to acquire the anisotropic properties. Longitudinal and transverse specimens were prepared for these anisotropic dressing products (or layers), as follows. Three longitudinal 'dog‐bone'specimens (cut along the direction of the spine, as per manufacturer instructions for use or shape directionality) as well as 3 transverse 'dog‐bone'specimens were prepared, separately for each dressing layer.

All the dressing product specimens were then tested in tensile loading, by means of an electromechanical uniaxial testing system (Z005, Zwick/Roell, Ulm, Germany) operating at a quasi‐static strain rate of 100%/min (0.0167 s−1). Stress‐strain pair values were calculated from the raw force‐displacement data obtained in each trial, by means of the “Origin” software (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA 01060 USA) and using the undeformed length and cross‐sectional area of each 'dog‐bone' shaped test specimen, as per the aforementioned testing standard. Corresponding elastic moduli were then calculated from the resulting stress‐strain curves for each dressing layer, per each structural direction (ie, longitudinal/transverse) where applicable, and for each product type. The elastic modulus was determined in each case as the linear slope of the empirical stress‐strain curve for the 0% to 20% strain domain, thereby representing the expected (large‐deformation) use of the tested dressings in clinical scenarios, that is, when subjected to the sacral forces of a bedridden supine person. All the above mechanical tests were conducted in a specialised environmental chamber mounted on the testing machine, at an ambient temperature of 35°C and relative humidity of 40%, to simulate the realistic microclimate conditions that apply for a prophylactic sacral dressing between the supine body of a patient and a support surface. 12 , 18 , 30 , 31 The measured elastic moduli of the layers of the tested dressing products are listed in Table 2. The Poisson's ratios of all dressing layers were assumed to be 0.45, consistent with the hyperelastic behaviour that all the tested dressing materials exhibited.

TABLE 2.

The material parameters of the layers of the (dry) tested dressing products which have been incorporated in the present modelling

| Dressing type | Outer layer (kPa) | Middle layer (kPa) | Inner layer (kPa) | Additional Layer (kPa) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L | T | L | T | L | T | Poisson's ratio | |||

| SF product #1 | 3190 ± 4.7 | 3580 ± 20.5 | 160 ± 15.5 | 150 ± 12.5 | 2330 ± 85 | 2317 ± 47 | ‐ | ‐ | 0.45 |

| SF product #2 | 5133 ± 249 | 5300 ± 245 | 263 ± 19 | 185 ± 4.1 | 2417 ± 62 | 2850 ± 50 | ‐ | ‐ | 0.45 |

| SF product #3 | 2900 ± 82 | 2250 ± 40.8 | 221.6 ± 4.7 | 121.6 ± 2.4 | 2117 ± 62.4 | 1850 ± 40.8 | ‐ | ‐ | 0.45 |

| SF product #4 | 9733 ± 330 | 11 500 ± 816 | 160 ± 8.2 | 163 ± 17 | 2180 ± 21.6 | 1857 ± 42 | ‐ | ‐ | 0.45 |

| RSB | 15 500 ± 1080 | 16 000 ± 408 | 7133 ± 125 | 2266 ± 94 | 3650 ± 204 | 3913 ± 66 | 58 333 ± 2494 | 25 333 ± 2495 | 0.45 |

Note: The outer layer is the layer facing the mattress (“backing film”) and the inner layer is the layer facing the skin. For the one dressing case which includes an “additional layer”, this additional layer is located between the middle and the outer dressing layers (as shown in Figure 2). L, longitudinal direction of the dressing (along the direction of the spine); T, transverse (or lateral) direction. SF, silicone‐foam; RSB, resposorb silicone border. Values are presented as the mean ± SD of the pooled test data for each dressing layer case.

In addition to the above tensile testing, compression tests were also conducted for each whole dressing product (the individual dressing layers were often too thin for allowing compression testing in isolation, that is, without bias due to boundary effects). For the compression tests, the centre of each dressing product was placed (with the skin side of the dressing facing downwards) on a horizontal rigid surface and below a flat, circular (6 cm in diameter) testing jig of the aforementioned electromechanical testing machine. The compression jig was again lowered quasi‐statically, at a speed of 50%/min (0.0083 s−1) towards the dressing surface. Each dressing product type has been tested 3 times. For these compression tests, the resulting force‐displacement curves were highly non‐linear and, therefore, rather than calculating a compressive elastic modulus, the acquired compressive test data were used to represent the non‐linear elasticity of the foam or cellulose fluff material components in the cores of the tested dressing products. This was achieved by assigning the empirically documented non‐linear stiffness laws in each dressing case to spring elements in the respective FE model variants. We further surmised that potentially, in some clinical scenarios, the compressive stiffness behaviour of the different dressing properties may be affected by moisture, for example, due to wet bedsheets. Accordingly, the same procedure of specimen preparation and mechanical testing was repeated after wetting an additional, equally‐sized set of specimens with distilled water that were uniformly applied to the outer, mattress‐facing side of the dressings (also known as the “backing film”), at a spray density of 0.15 mL/cm2, to simulate dressing usage in moist conditions. The non‐linear stiffness laws incorporated for each tested dressing are provided in Table 3 (separately for the dry and moist testing conditions) in the form of the coefficients of the best fit to a tri‐linear function (in terms of the root mean square error) per each product and dry/moist condition. The force‐displacement curves of all dressing products, fitted the a tri‐linear representation (for which coefficients of the fits are provided in Table 3), for the dry and moist test conditions are shown in Figure 3.

TABLE 3.

The non‐linear elastic stiffness laws incorporated in the modelling for each tested dry or moist dressing, which were represented here by approximating the empirical compressive force‐displacement data using a tri‐linear function

| Dressing type | A (N/mm) | B (N/mm) | C (N/mm) | Displacement of transition from slopes A to B (mm) | Displacement of transition from slopes B to C (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dry | |||||

| SF product #1 | 0.0020 | 0.0203 | 0.0878 | 3.01 | 4.20 |

| SF product #2 | 0.0091 | 0.0565 | 0.2011 | 1.25 | 1.66 |

| SF product #3 | 0.0064 | 0.0498 | 0.2016 | 1.00 | 1.73 |

| SF product #4 | 0.0078 | 0.0265 | 0.2213 | 1.51 | 2.35 |

| RSB | 0.0040 | 0.0403 | 0.1679 | 1.24 | 1.77 |

| Moist | |||||

| SF product #1 | 0.0037 | 0.0071 | 0.0312 | 1.98 | 4.03 |

| SF product #2 | 0.0053 | 0.0568 | 0.2037 | 1.81 | 2.33 |

| SF product #3 | 0.0110 | 0.0750 | 0.2162 | 1.36 | 1.73 |

| SF product #4 | 0.0096 | 0.0607 | 0.2622 | 2.00 | 2.48 |

| RSB | 0.0099 | 0.0919 | 0.2198 | 0.99 | 1.38 |

Note: F is the compressive force, d is the resulting (absolute magnitude of) the displacement of the dressing subjected to compression, and A, B, C are the first, second and third slopes of the tri‐linear best fit which are reported below (in units of N/mm). The second linear segment (with slope B) and third linear segment (with slope C) are reached at displacements d A‐B and d B‐C, respectively. The above stiffness formulation and the corresponding coefficients below should be considered as representing an area of 1 mm2 of each dressing. SF, silicone‐foam; RSB, resposorb silicone border. Values are presented as the mean of the pooled test data for each dressing case. The data points of the best fits are also depicted graphically in Figure 3 for visualisation of the compressive stiffness behaviour of each tested dressing product.

FIGURE 3.

The compressive force‐displacement curves of all the tested dressing products, fitted to a tri‐linear function (for which the coefficients resulting from the best fits to the test data of each dressing product are provided in Table 3), for dry (A) and moist (B) test conditions. The stiffness relationships shown here should be considered as representing an area of 1 mm2 of each dressing. SF, silicone‐foam; RSB, resposorb silicone border

The coefficient of friction (COF) data between a new cotton linen and the outer surface of each dressing product were also determined in rigorous laboratory tests which are described as follows. The COF measurements were performed using a specialised rotary tribometer for solid‐solid contact studies (produced by the Materials Research Institute (Institut für Materialforschung) of the University of Aalen, (Hochschule Aalen), Germany). Only whole dressing products (not individual layers) were tested for their COF. Similarly to the other mechanical property studies reported above, the COF tests were conducted in dry and moist conditions, where distilled water at a spray density of 0.15 mL/cm2 were applied to the outer, mattress‐facing (backing film) surface of the dressings. Each product was tested three times and all friction tests were conducted in an environmental chamber under the aforementioned ambient conditions. Each dressing product was attached to a fixed flat steel surface with a diameter of 6 cm, using the inherent adhesive interface of the product where applicable. Some of the products did not have an integral adhesive feature and hence, double sided adhesive was used to fix the skin‐facing side of these dressings to the aforementioned steel basis. The rotating counterpart of the tribometer, a flat steel disk, was coated with a new cotton fabric that was fixed to this disk using double‐sided adhesive strips. The rotating disk element was then pressed to the dressing with a force of 50 N to ensure full contact. The disk was then rotated at an increasing speed and the applied torque was measured. 32 From the resulting torque‐speed curves, the static COF 3 was extracted for each dressing case; the COF is the proportionality coefficient between the applied torque and angular velocity of the cotton‐coated disk when rubbing against the outer dressing surface. 32 , 33 The measured static COF data are summarised in Table 4.

TABLE 4.

The measured static coefficients of friction (COF) data for the outer surface of the tested dressings (also known as the 'backing film', i.e., the dressing surface which faces the mattress) against new cotton linen in dry and moist test conditions

| Dressing type | COF | |

|---|---|---|

| Dry | Moist | |

| SF product #1 | 0.44 ± 0.03 | 0.43 ± 0.02 |

| SF product #2 | 0.44 ± 0.05 | 0.34 ± 0.04 |

| SF product #3 | 0.50 ± 0.04 | 0.35 ± 0.02 |

| SF product #4 | 0.43 ± 0.09 | 0.46 ± 0.06 |

| RSB | 0.36 ± 0.02 | 0.41 ± 0.04 |

Note: SF, silicone‐foam; RSB, resposorb silicone border. Values are presented as the mean ± SD of the pooled data for each dressing case.

In order to represent the stiffness of the support surface under the supine body in the modelling, the foam material of the mattress was considered homogeneous, isotropic, and linear‐elastic for simplification of the frictional contact problem. Two different elastic moduli were assigned to the modelled mattress for a sensitivity test, 10 kPa (softer mattress), and 30 kPa (stiffer mattress), to account for the possible range of the commercially available standard medical foam mattresses, including high‐specification mattresses. 34 , 35 , 36

2.3. Boundary conditions

At the superior and inferior anatomical surfaces of the model, that is, the torso and thighs, symmetry conditions were applied, that is, all deformations in the longitudinal direction of the body (spine) were fixed. The ends of the bones were rigidly clamped. The bottom of the mattress has been fixed as well, for all translations and rotations.

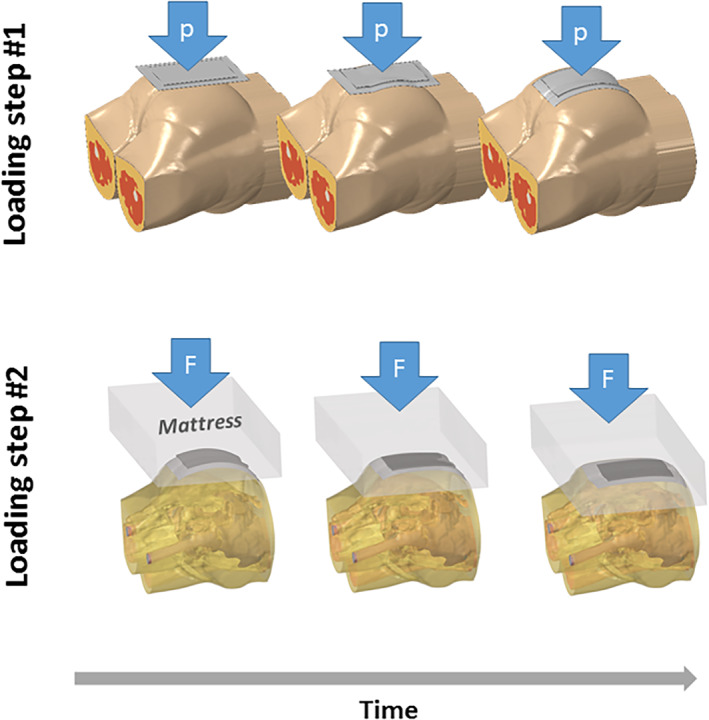

The loading of each of the FE model variants has been divided into two steps, simulating (i) the application of each sacral prophylactic dressing and (ii) positioning the patient in a supine position (Figure 4). In the first loading step, a specific dressing product was applied to the buttocks model using a minimal pressure load which has been gradually increased up to 0.2 kPa and with no friction, to prevent folding of the dressing structure in the following loading step, when the buttocks are simulated to bear the full bodyweight of the supine person. This first loading step simulates, in fact, the pressure applied on the dressing by a nurse during an adequate dressing application action, where a nurse would attach the dressing to the skin surface while maintaining it smooth and free of folds and wrinkles. After application of the dressing, the above pressure load has been removed so it had no influence on the simulation results. In the second loading step, the contact between the skin and the dressing was fixed to simulate the adhesiveness feature of prophylactic dressings. The bodyweight forces were then applied gradually, by moving the mattress towards full contact with the buttocks at a constant speed of 110 mm/s. This movement resumed until a buttocks‐mattress reaction force of 290 N (ie, approximately 29.6 kg) has been reached, which approximates the fraction of the weight of the buttocks of the person scanned in the MRI with respect to her total body weight. Once a reaction force level that represents this weight fraction that should be 40% according to Plagenhoef et al 37 has been achieved, the speed of the mattress was reduced to zero and any dynamic effects were allowed to decay. The steady‐state simulation condition for each dressing case, reached at the end of the second step of the loading process, thereby represents a motionless supine human body resting still on the mattress after application of a sacral prophylactic dressing (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

The two steps of loading the model variants for simulating the application of a prophylactic sacral dressing and then further calculating the tissue loading state in a resting supine body position. p = the minimal pressure level (up to 0.2 kPa) simulating the pressure applied on the dressing by a skilled nurse during the action of dressing application, to attach the dressing to the skin surface while maintaining it smooth and free of folds or wrinkles. F = the reaction force between the mattress and the supine body which is increased gradually (until reaching 40% of the bodyweight which simulates full weight‐bearing based on anthropometrical data). The loading process is shown here from an inferior view, so that the sacral prophylactic dressing can be seen

2.4. Numerical method

The 3D geometry reconstruction of the female buttocks was imported to an FE solver (ABAQUS, Dassault Système, Vélizy‐Villacoublay, France) for meshing. All tissue types were meshed using tetrahedral elements (type C3D4H in ABAQUS). The model (without a dressing) consisted of approximately 3.6‐million elements, distributed as follows: bone 229 000, adipose 2 212 000, skeletal muscle 755 000, and skin 454 000 elements. The dressings and the mattress were meshed using hexahedral elements (type C3D8I in ABAQUS). There were approximately 40 000 to 60 000 elements in the different dressing structures (depending on the specific dressing type) and 62 000 elements in the mattress. To account for the compressive non‐linearity of the core of the tested dressings, non‐linear springs (type SPRINGA in ABAQUS) were added to the dressing elements to represent the hyperelastic behaviours of their foam or cellulose fluff components (Table 3). Mesh refinements were applied locally and manually where required, particularly at the skin‐dressing‐mattress interfaces, to augment numerical convergence despite the sharp material stiffness gradients and potential element shape distortions where high surface curvatures existed (which typically causes challenges in solving FE numerical problems). Likewise, mesh refinements were used to support convergence in the model locations where there has been direct transition from relatively thick tissue structures to the thin dressing layers.

Multiple numerical tests were further conducted to minimise the influence of mass scaling and velocity while reducing the calculation times, which resulted in the aforementioned mattress velocity of 110 mm/s (for the second loading phase, simulating the positioning of the patient supine after application of the dressing) and also, a mass scaling of 10%. All calculations were performed in a 3D dynamic explicit analysis and using the two loading steps as described above (Figure 4). The time for solving the FE model variant without a dressing was 14 hours whereas the model variants with dressings required a range of 15 to 18 hours to reach full numerical convergence, depending on the specific dressing type. The computer system used for all the present FE analyses was a dedicated heavy‐duty workstation for high‐end FE analyses: 64‐bit Linux‐based system with a central processing unit containing an Intel Xeon E5‐2697A v4 processor, operating at a clock speed 2.6 GHz and with 256 Gigabytes of random access memory.

2.5. Protocol of simulations and biomechanical outcome measures

Each FE model variant with a certain dressing product was solved in simulations of dry and moist dressing conditions, and where the buttocks were supported by the softer (10 kPa) or stiffer (30 kPa) mattress. This resulted in a set of four solutions for each model variant: (i) Dry dressing on soft mattress, (ii) dry dressing on stiff mattress, (iii) moist dressing on soft mattress, (iv) moist dressing on stiff mattress. For each such solution, effective von Mises stresses were analysed in a cubic volume of interest (VOI) with dimensions of 9 × 9 × 9 cm3, which contained the soft tissue structures located directly under the sacrum and coccyx that are, therefore, at the highest risk for development of a sacral PU in a supine patient (Figure 5). For the presently studied anatomy, the volume fractions of tissues (representing the soft tissue composition in the undeformed model configuration) were 2.1% skin, 84.4% adipose, and 13,4% muscle.

FIGURE 5.

The volume of interest (VOI) in the modelling (with dimensions of 9 × 9 × 9 cm3) containing the soft tissue structures located directly under the sacrum and coccyx, which are at the highest risk for development of a sacral pressure ulcer in a supine position

For the purpose of analysing the exposure of soft tissues in the above VOI to the sustained stresses associated with the supine position, effective stress data from the elements contained in the VOI were analysed as follows. First, we plotted the volumetric distribution of the effective stress magnitudes in the VOI, following the stress exposure histogram (SEH) chart methodology developed in our published work. 13 , 14 , 15 , 17 , 20 A SEH chart has been prepared for each dressing case and for each combination of dry/moist dressing conditions and soft/stiff mattress conditions per each dressing type (4 SEH per dressing type). A SEH chart for the no‐dressing case was further prepared, as the reference chart. We then systematically compared the volumetric exposures of soft tissues to stresses in the VOI across the FE model variants with the different dressing types, using the no‐dressing case as the basal condition.

The protective efficacy index (PEI) defined in our previous work 15 , 17 has been employed here as a scalar (single value) comparator of the biomechanical performances of the different dressings (in either dry or moist conditions). For a given dressing, the PEI is the percentage‐difference in the area under the SEH chart for a given applied dressing (A d) relative to the no‐dressing case (A nd):

| (1) |

From a theoretical perspective, the area under the SEH curve should reduce if a good effective prophylactic dressing is applied. If the difference in the area under the SEH curve for the no‐dressing case with respect to the selected dressing data, A nd − A d, is minimal, the PEI would approach zero, indicating an ineffective dressing that is unable to reduce the stress exposure and is, therefore, not delivering tissue protection. The more biomechanically effective a dressing is in reducing the stress exposure in the VOI, the lower its SEH curve would be (with respect to the no‐dressing curve), resulting in a greater A nd − A d difference, and accordingly, a higher PEI value (Equation (1)). Considering that it is the exposure to relatively high stresses which may compromise soft tissue health, only the effective stress domains above the median value of the basal (no‐dressing) simulations were considered for calculations of the PEI values per each dressing case.

After separately calculating the PEI of each dressing in its dry and moist conditions, the protective endurance (PEN) can further be calculated, as 15 :

| (2) |

Ideally, for a good dressing which biomechanically performs identically when being either dry or moist (ie, the PEI of such dressing in its moist state equals its PEI in its dry state), the PEN will be 100%. Another example illustrating the use of the PEN parameter (Equation (2)) would be of a dressing that, when moist, induces tissues stresses that are near those where no dressing is present (ie, its PEImoist will be close to 0%) and in such case, its PEN will be approximately zero. When used together, Equations (1) and (2) indicate that a good prophylactic dressing should have both high PEI and PEN values. 15 , 17

The PEI and PEN data have been calculated separately for just the skin in the VOI and for the pooled layers of the soft tissues (ie, for the entire VOI composing skin, adipose, and muscle tissues altogether), in order to isolate the superficial protective effect of each dressing on the skin (only), from the corresponding protective effect projected into subdermal and deeper tissues. We further calculated the PEI and PEN data separately for the softer (10 kPa) mattress and for the stiffer (30 kPa) mattress. As explained above, we used the median tissue stress values of the no‐dressing simulations as the basal stress thresholds for these PEI and PEN calculations. For the softer (10 kPa) mattress, the basal stress thresholds were 23.9 kPa and 0.3 kPa for the skin (only) and pooled soft tissues, respectively; for the stiffer (30 kPa) mattress, the basal stress thresholds were 19.2 and 0.33 kPa for the skin and pooled soft tissues, respectively. Of note is that the median skin stresses for the bare skin were moderately greater on the softer mattress as the exposed sacral skin tissue is stretched more on the softer mattress (but not necessarily so when being protected by a prophylactic dressing).

Finally, as a potential trade‐off (interaction) effect may exist between the protective performances of a new (“out of the package”) dry dressing product and the ability of that same product to deliver a similar extent of protective efficacy over the time of use (when absorbing moisture), the prophylactic trade‐off design parameter (PTODP) was calculated for each tested product, as:

| (3) |

Of note is that the aforementioned definition of the PTODP follows the classic definition of an interaction term in statistics, which is an explicit multiplication of the two relevant variables (PEIdry and PEImoist). The higher the PTODP value (Equation (3)), the better is the trade‐off point between delivery of tissue protection when the product is new (from the package) and its ongoing protective efficacy when that product absorbs moisture over time. In other words, a good dressing product should have a relatively high PEIdry value (reflecting its prophylactic performances when it is new) as well as a relatively high PEImoist (reflecting its ability to maintain its performances while in use), which both contribute to a high PTODP.

Taken together, the PEI, PEN, and PTODP indices create a minimum dataset (MDS) which objectively and quantitatively characterises the protective biomechanical performances of any prophylactic dressing of interest, when being new out of the package (PEI), in its used condition after absorbing moisture (PEN) and, when combining these two states in the lifecycle of a dressing (PTODP). The latter, PTODP index is of particular importance, as it evaluates the adequacy of the balance between the 'new' and 'used' performances of the same product. Calculation of each of these indices for dressings evaluated under the same testing conditions, therefore, allows robust and systematic comparisons of new or existing product performances.

3. RESULTS

The different dressing products exhibited distinct mechanical (Table 2) as well as structural (Table 3) stiffness behaviours, as well as different friction characteristics (Table 4) which (as could be expected) resulted in substantially different protective performances, as detailed below. Noteworthy is the structural stiffness of the tested dressings in compression, which not only varied across products in the dry condition, but was also not necessarily consistent between the dry and moist test conditions for the same product (Figure 3). For example, the RSB dressing which was shown to be relatively soft and compliant at a dry (new) state (Figure 3A) has approximately doubled its structural stiffness after being exposed to moisture and became the stiffest product in compression (Figure 3B), likely due to a swelling effect in its backing film 4 (Figures 2, 3).

The SEH charts of the different dressing products that were studied here are shown in Figure 6 (for the softer, 10 kPa mattress and separately, for the stiffer, 30 kPa mattress, in panels (A) and (B), respectively). Associated with the above‐reported variations in mechanical and structural stiffness behaviours across the different products, these SEH curves demonstrate substantial variability in skin and pooled soft tissue (effective) stress exposures among these products, and even within the silicone‐foam product family.

FIGURE 6.

The stress exposure histogram (SEH) charts of the different dressings under dry (left column) and moist (right column) test conditions, for the skin and pooled soft tissue layers (skin, adipose and skeletal muscle tissues considered together) in the upper and lower panels, respectively, for the softer (10 kPa) mattress (A) and the stiffer (30 kPa) mattress (B). The SEH data in the sacral volume of interest (VOI; demarcated in Figure 5) are shown on a semi‐logarithmic scale. The no‐dressing SEH charts (continuous red lines, plotted starting from the median stress value on the horizontal axes) were considered the basal condition for the calculations of the protective efficacy index (PEI), protective endurance (PEN) and prophylactic trade‐off design parameter (PTOD) values (detailed in Tables 5, 6 and 7, respectively) for each tested dressing product. SF, silicone‐foam; RSB, resposorb silicone border

Our concept of an MDS to characterise the prophylactic performances of dressings, which is realised here using the PEI, PEN, and PTODP indices, facilitated objective, quantitative, standardised, and robust comparative analyses, which are reported as follows. The PEI data for the silicone‐foam dressings are reported in Table 5, separately for the skin and pooled soft tissue layers (skin, adipose, and muscle altogether). The comparison of the mean PEI of the silicone‐foam products (lumped together) vs the inherently different design of the RSB dressing (with its soft cellulose fluff core) is depicted using bar graph plots in Figure 7, again, separately for the skin and pooled soft tissue layers. The data in Table 5 and Figure 7 revealed the following phenomena: (i) Generally, the PEI values of dressings for skin tissue (alone) are greater than those calculated for the pooled soft tissues. (ii) The PEI values of dressings for a person positioned on the softer (10 kPa) mattress were overall greater than those obtained for the stiffer (30 kPa) mattress. (iii) The means of the PEI values of the silicone‐foam dressings were marginally influenced by the presence of moisture, although there was variability in the extent of the impact of moisture across the different silicone‐foam dressing types, which grew for the stiffer mattress cases (Figure 7). The PEI data of the RSB dressing was more predominantly affected by moisture, excluding in the case of skin (only) on the softer mattress. (iv) Apart from the PEI of skin for the softer mattress case, where the PEI values were similar between RSB and the respective means of the silicone‐foam dressings, the PEI values of the RSB dressing were always substantially greater than those of the corresponding mean silicone‐foam PEI data. The differences in the PEI data between the RSB and the silicone‐foam dressings increased for the stiffer mattress with respect to the softer mattress case. The PEI property ratios of interest to distinguish between the performances of the fluff‐core RSB dressing design and the silicone‐foam dressings are the ratios of the PEI for RSB dressings over those of the corresponding means of the silicone‐foam dressings. For the stiffer mattress cases, these property ratios were 1.4 and 1.2 for the dry and moist dressing conditions, respectively, when considering skin only. These PEI property ratios were even greater, 2.2 and 1.7 for the dry and moist dressing conditions, respectively, when considering the pooled soft tissue structure altogether. This indicates that the PEI of a new RSB dressing would be between 20% and 40% more than those of silicone‐foam dressings as concerned the protection of skin, and between 70% and 120% above those of silicone‐foam dressings in protecting deeper soft tissues near the sacrum.

TABLE 5.

Calculated protective efficacy index (PEI) values for the different dressing types

| Skin | PEI (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Softer mattress | Stiffer mattress | |||

| Dry | Moist | Dry | Moist | |

| SF product #1 | 96.5 | 94.2 | 35.9 | 26.4 |

| SF product #2 | 98.4 | 98.6 | 60.7 | 61.9 |

| SF product #3 | 99.2 | 99.2 | 67.7 | 67.3 |

| SF product #4 | 97.4 | 97.4 | 61.1 | 61.3 |

| RSB | 98.1 | 97.1 | 76.5 | 67.5 |

| Pooled soft tissues | ||||

| SF product #1 | 13.8 | 13.8 | 2.4 | 2.4 |

| SF product #2 | 13.1 | 13.4 | 4.7 | 4.3 |

| SF product #3 | 16.8 | 16.9 | 8.3 | 8.5 |

| SF product #4 | 14.7 | 14.7 | 5.7 | 5.7 |

| RSB | 20.7 | 17.3 | 11.6 | 8.9 |

Note: The softer and stiffer mattresses were assigned elastic modulus values of 10 and 30 kPa, respectively. SF, silicone‐foam; RSB, resposorb silicone border.

FIGURE 7.

The protective efficacy index (PEI) of the Resposorb silicone border (RSB) dressing vs the corresponding mean PEI of the silicone‐foam (SF) dressings for skin only (A) and the pooled soft tissues (B) (skin, adipose and skeletal muscle tissues considered together). The error bars denote the standard errors of the means (n = 4 SF dressings)

The PEN data for the presently tested dressings are reported in Table 6, separately for the skin and pooled soft tissue layers. The comparisons between the PEN of RSB dressings and the mean PEN data of the silicone‐foam products (taken together) are depicted in Figure 8A, likewise, separately for skin and the pooled soft tissue layers. The PEN property ratios of interest, which, consistent with the above (PEI) analyses, are the ratios of the PEN for RSB dressings over those of the respective means of the silicone‐foam dressings, were equal or less than unity, that is, for skin only, they were 1 and 0.9 for the softer and stiffer mattresses, respectively. For the pooled soft tissues, these PEN property ratios were 0.8 for both the stiffer and softer mattresses. These PEN property ratio data (Table 6 and Figure 8A) indicate that the silicone‐foam dressing designs overall handle fluids better, with their prophylactic performances being less affected when moisture accumulates in the dressing.

TABLE 6.

Calculated protective endurance (PEN) values for the different dressing types

| Skin | PEN (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Softer mattress | Stiffer mattress | |

| SF product #1 | 97.6 | 73.7 |

| SF product #2 | 100.2 | 101.9 |

| SF product #3 | 100.0 | 99.4 |

| SF product #4 | 100.1 | 100.4 |

| RSB | 98.6 | 88.2 |

| Pooled soft tissues | ||

| SF product #1 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| SF product #2 | 102.6 | 90.3 |

| SF product #3 | 100.7 | 102.3 |

| SF product #4 | 100.1 | 100.6 |

| RSB | 83.5 | 76.9 |

Note: The softer and stiffer mattresses were assigned elastic modulus values of 10 and 30 kPa, respectively. SF, silicone‐foam; RSB, resposorb silicone border.

FIGURE 8.

The protective endurance (PEN) (A) and prophylactic trade‐off design parameter (PTODP) (B) of the Resposorb silicone border (RSB) dressing vs the corresponding means of the silicone‐foam (SF) dressings for skin and the pooled soft tissues (skin, adipose and skeletal muscle tissues considered tgether) on the softer (10 kPa) and stiffer (30 kPa) mattresses. The PTODP data are plotted on a semi‐log scale. The error bars denote the standard errors of the means (n = 4 SF dressings)

The ultimate measure of the prophylactic performances of a dressing over time is the PTODP index, which concurrently considers the performances at the 'new' and “used” states of the same dressing and hence, evaluates the balance between the performances at the corresponding two extreme time points in the lifecycle of a dressing (Equation (3)). The PTODP data for RSB dressings and the silicone‐foam dressings are reported in Table 7, separately for the skin and pooled soft tissue layers. The comparisons of the PTODP values of RSB dressings against the corresponding PTODP means of the silicone‐foam products (taken together) are depicted in Figure 8B, similarly, separately for the skin and pooled soft tissue layers. These PTODP data, which weigh the performances of a new (from‐the‐package) dressing and an identical used dressing (exposed to moisture), clearly demonstrate superiority of the RSB product in 3 of the four relevant test conditions (ie, the possible combinations for just skin or the pooled soft tissues, and when the patient is on either a softer or a stiffer mattress). Specifically, the relevant PTODP property ratios, that is, the ratios of the PTODP for RSB dressings over those of the respective means of the silicone‐foam dressings were 1 and 1.59 for just skin on the softer and stiffer mattress, respectively, and 1.65 and 3.2 for the pooled soft tissues on the softer and stiffer mattress, respectively. In other words, the PTODP of the RSB dressing is at least equal, and potentially 59% more than those of silicone‐foam dressings for skin in the sacral region, and is 65% to 220% above those of silicone‐foam dressings with respect to protecting deeper sacral soft tissues.

TABLE 7.

Calculated prophylactic trade‐off design parameter (PTODP) values for the different dressing types

| Skin | PTODP (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Softer mattress | Stiffer mattress | |

| SF product #1 | 90.9 | 9.5 |

| SF product #2 | 97.0 | 37.6 |

| SF product #3 | 98.4 | 45.6 |

| SF product #4 | 94.9 | 37.5 |

| RSB | 95.3 | 51.6 |

| Pooled soft tissues | ||

| SF product #1 | 1.9 | 0.1 |

| SF product #2 | 1.8 | 0.2 |

| SF product #3 | 2.8 | 0.7 |

| SF product #4 | 2.2 | 0.3 |

| RSB | 3.6 | 1.0 |

Note: The softer and stiffer mattresses were assigned elastic modulus values of 10 and 30 kPa, respectively. SF, silicone‐foam; RSB, resposorb silicone border.

To summarise, the results of our present comprehensive experimental‐computational analyses focusing on the prophylactic performances of RSB dressings vs silicone‐foam products determined that the RSB dressing is as‐good or, in most cases, superior to silicone‐foam dressings, across all the PEI indices as well as for 3 of the 4 PTODP indices. While RSB dressings exhibited moderately lower PEN values, that is, mildly less protection than the silicone‐foam dressings for the moist (used) conditions, it did provide the best balance between protective performances “out‐of‐the‐package” and performances when absorbing moisture after a period of use. In fact, the present data implies that if RSB dressings are to be used prophylactically and would be replaced more frequently than the silicone‐foam products (and thereby, the RSB dressings will always be at their near 'out‐of‐the‐package' condition), the fluff‐core design of the RSB dressing would deliver better superficial as well as deep tissue protection with respect to silicone‐foam dressings.

4. DISCUSSION

In this paper, we systematically compared the biomechanical efficacies of two fundamentally different dressing technologies for preventative use: A new fluff‐core based (RSB) dressing technology with respect to the mainstream silicone‐foam dressings. Using an anatomically‐realistic, 3D FE modelling framework representing a young‐old female patient positioned supine on two mattress types and to whom different sacral dressings have been applied, we quantitatively evaluated the efficacy of each applied dressing. The dressings were evaluated at a simulated “new from the package” condition, as well as post‐use, based on rigorous experimental laboratory work during which we have measured the mechanical and frictional properties of the new dressings and after exposing them to moisture. A set of performance parameters characterising the quality of the delivered prophylactic protection: PEI, PEN, and PTODP have been calculated from this integrated experimental‐computational analysis. The values of the aforementioned indices have been compared across the dressing types (Tables 5, 6, 7) and then specifically, between the RSB product and silicone‐foam dressing family (Figures 6, 7, 8).

The silicone‐foam dressing technology, characterised by a sandwich‐like structure of multiple foam and silicone layers, is currently the market‐dominant for PUP by means of prophylactic dressings. Likely due to historical reasons, no alternative design concepts have been offered in the advanced dressing market so far, and so there were no real incentives for questioning whether the silicone‐foam concept is the only solution or the paramount approach for prophylaxis. In a broader context, at this time, no commercially available dressing has been designed (from scratch) specifically for prophylaxis or is recommended for just this purpose. Current market trends actually favour dual use of the same dressing in prevention and treatment. Such dual use is advantageous in multiple aspects, including allocation of manufacturing capacities and equipment, logistics, and storage at both the manufacturer and client ends, ease and simplicity of use and conduct of training and education that focuses on one product which covers the continuum of care ‐ from prevention to treatment. Nevertheless, from a bioengineering design viewpoint, a dual use dressing should be effective in delivery of both prophylaxis and treatment, which is a considerable and complex engineering design challenge.

Even from just a preventative perspective, a good prophylactic outcome depends on several design features that should work synergistically and in a balanced, well‐adjusted mechanism of action within a dressing. A good analogue for explaining this would be a running shoe that biomechanically functions to protect the body and tissues of an athlete from a musculoskeletal injury. For adequately achieving this goal, the sole of the shoe needs to have a certain COF with the ground that is not too little (or otherwise the athlete will slip) nor too high (which will require excessive forces and energy for propulsion). Likewise, the materials of the shoe sole structure should be light, soft, and comfortable but still be effective in redistributing the body‐shoe reaction forces and dissipating mechanical energy so that the shock waves transmitted to the musculoskeletal structures with each heel strike during running are minimised. Finally, the shoe should not accumulate excess heat and allow good conduction of the metabolic and frictional heat and its release to the environment, in order to not promote build‐up of perspiration‐induced moisture that induces a risk of skin maceration. These different considerations each reflect on the selection of materials, the composition, and shape of the shoe whereas meeting one design target, for example, good pressure redistribution should not compromise other design targets such as a good thermal conductivity. In fact, each of the above design factors (which have been listed for the running shoes) exists in the context of prophylactic dressings: (i) The requirement to have a relatively low (but not too low 5 ) COF of the backing film with the mattress; (ii) Effective dissipation of mechanical energy through shape conformation and internal dressing deformations which results in pressure redistribution and alleviation of internal tissue loads; and (iii) Thermal conductivity properties that would allow excessive heat to leave the skin‐dressing interface. In the present work, we focused on the prophylactic function of (dual use) dressings, and within the prophylactic domain, we considered the biomechanical but not the bio‐thermal factors (which are addressed in our other recently published work, for example, 18 , 30 ). Specifically, we investigated the performance of biomechanical alleviation of internal (skin and deeper) tissue stresses by means of the two different dressing design concepts: cellulose fluff core vs a silicone‐foam sandwich.

In addition to the requirement of adequately choosing and balancing the material selection, structure, composition, and shape for achieving the desired frictional behaviour, energy dissipation and eventually, sufficient relief of the tissue loading state, one needs to consider the critical issue of durability in any dressing design. Durability is the ability of a dressing to withstand real‐world factors that may affect its efficacy and in the context of prophylaxis, the primary factor is the exposure to moisture. 15 Moisture may apply on the mattress‐facing side of a dressing (the backing film) when, for instance, the bedsheets become wet due to incontinence. Under such moist conditions, the compressive stiffnesses of any dressing might be affected, for example, as wet foams are often softer than dry ones. 39 This is indeed demonstrated in our present data, as a shift to the right (or “flattening”) of the compressive force‐displacement curve from the 'dry' to the 'moist' testing condition, for some of the dressing products evaluated here, specifically for product #1 (Figure 3). Hence, it is critically important to not only assess dressing performances in their new, out‐of‐the‐package condition but also, to test them after exposing the products to moisture and wetness, as will very likely happen in real‐life. In addition, other real‐world conditions need to apply for the laboratory work to replicate the probable clinical scenarios, such as a testing temperature above the ambient temperature (simulating the skin temperature which in most cases will be greater than the room temperature), or the interaction of a dressing with the mattress (while representing a variety of mattresses that are available in different clinical settings). The present experimental‐computational study considered all these factors together, including their potential interactions (eg, the combined effects of the moisture and mattress stiffness).

The parameter which describes the biomechanical efficacy of a dressing used prophylactically in alleviating tissue loads when the dressing is new from the package is the PEI. 17 Its counterpart, describing the capacity of a dressing to still deliver a similar protective outcome when being moist post‐use is the PEN. 15 A new and important theoretical addition in the present study is the PTODP index, which weighs the PEIdry and PEImoist parameters together, to quantify the balance between biomechanical performances of the same dressing in its new and used conditions. Correct application of these three indices is in technology and product comparisons, which can then reflect the relative adequacy of the selection of the specific technology as well as the design choices that have been made in deciding on the dressing materials, structure, composition, and shape. Here we have used the PEI, PEN, and PTODP set of parameters for systematic comparisons between two inherently different dressing technologies: The market‐dominant technology which is currently a silicone‐foam sandwich‐like dressing structure, vs the RSB dressing which has a core of soft cellulose fluff blended with a fluid‐retaining super‐absorber. Importantly, the comparison made here only reflects the preventative, but not the treatment capacitates of these two different technologies, and with respect to prophylaxis, the focus has been on alleviating the sustained soft tissue loads but the heat release aspect has not been addressed and requires a future study.

The PEI, PEN, and PTODP comparisons that were conducted between the silicone‐foam products and the RSB technology (Figures 7 and 8) indicate that as expected, the structure and composition of the different dressings play a critical role in their biomechanical performances. Even within the silicone‐foam dressing family, the tested dressings exhibited considerable variabilities with respect to all the aforementioned indices; these variabilities consistently grew for the stiffer (30 kPa) mattress conditions (with respect to a softer 10 kPa mattress) and for the moist conditions (PEI data in Figure 7). This result strongly reflects that the role of a prophylactic dressing in protecting soft tissues from sustained loads becomes more important on stiffer support surfaces, such as operating table pads or low‐end/thin mattresses and also, clearly, that the effect of moisture on dressings depends on the specific materials selected in the design process. Accordingly, although the PEI, PEN, and PTODP data of the silicone‐foam dressings were pooled together for visualisation and to contrast the combined silicone‐foam data from that of the RSB dressing (Figures 7 and 8), it should be highlighted that each dressing type performs differently, even if it falls under the same design concept of 'silicone‐foam', depending on its specific constituents. There are no generic or common performances of a certain technology in this regard. This point is critically important in the context of patient safety as well as with regards to cost‐benefit outcomes, as the clinical choice is not just between technology categories (eg, silicone‐foam vs a cellulose fluff core) but also, within a certain technology category, between products that deliver potentially different efficacies and at different financial costs. 11 , 40 Compared with the laborious and thoroughgoing regulatory processes in place within the pharmaceutical industry for extrapolation of clinical evidence of efficacy from one type of 'generic' technology to another, the dressing world has more uncertainty or indeterminacy. The main difference between a pharmaceutical drug and an advanced dressing is that there is only one possible way of producing a drug (which is as defined in its chemical formula), but, as highlighted in this work, there are practically infinite ways for an engineering design of a dressing (even if it belongs to the silicone‐foam or any other product family). As a result, in the industry of wound care devices and consumables, it is generally far more difficult to determine whether products that make the same medical claims of a clinical effect (or look‐alike products) are actually equivalent in effectiveness. This issue places undue responsibility on clinicians and administrators in the conduct of product selection and the present study highlights this critically important point. 11 , 40

Our data depicted in Figures 7 and 8 demonstrates that the RSB dressing is at least as‐good and in most cases, superior to the tested silicone‐foam dressings, with regards to all the PEI and 3 of the 4 PTODP indices. The RSB dressings exhibited somewhat lower PEN values than the silicone‐foam dressings, but still provided the best balance between protective performances at the “new” RSB dressing condition and the performance after being exposed to moisture, as evident from the PTODP index comparisons (Figure 8). Of note is that in order to make the best prophylactic use of these RSB dressings, our present results suggest that they should be replaced frequently to maximise their performance. If the more frequent RSB dressing changes will be applied in clinical practice, the RSB dressings will always be at their near‐'new' condition, where they perform superiorly to the silicone‐foam products in delivering skin and deeper tissue protection (Figures 7 and 8). Noteworthy is that any existing preventative dressing should be changed within a range of 3 to 7 days of use 5 , 7 , 8 and accordingly, the specific frequency of changes (within that relatively wide time interval) is also a trade‐off (optimization) problem of maximising performances and still meeting cost‐benefit goals. This aspect requires further research, including with respect to the RSB dressing.

Both experimental work and computational modelling involve assumptions and limitations that are associated with the chosen laboratory and numerical methods and should be discussed. 41 First, the human anatomy that has been studied here, although being MRI‐based and, therefore, anatomically‐realistic, is of a specific individual. Using FE model variants that incorporate the same subject‐specific anatomy and where only the dressing (and mattress) have been changed was deemed necessary, to be able to isolate the effects of the applied dressing on the loading state of soft tissues. However, this approach may underrepresent the impact of any anatomical variants, including those related to the gender and ethnic groups which may intensify or diminish the prophylactic effect of certain dressings, through their specific dressing‐body biomechanical interactions. In other words, we cannot rule out that in specific individuals with an at‐risk anatomy, such as persons with a bony structure, malnourished individuals, or people with atrophies, the differences in performances of the studied dressings may change (although the same trend of effect is still expected). Accordingly, future research should look into the effects of anatomies that differ substantially from the 50th‐percentile female studied here and specifically focus on male, obese, elderly, and atrophied patients. Likewise, the tissue stiffness properties used in the present modelling do not necessarily represent aging, chronic illness, atrophies, and other degenerative changes in tissues, so these factors should be considered as well in the work going forward. With regards to the simulated‐use protocol employed here for the tested dressings, it included wetting of the backing film of the dressings (ie, from the aspect of the mattress), which is more typical to wet bedsheets, but does not represent perspiration, which accumulates at the skin‐facing side of the dressings. In clinical practice, moisture can accumulate at both aspects of the dressing, that is, due to sweating from the skin side and also, because the bedsheets are wet (eg, if incontinence is involved) and so, there is room for laboratory studies of these scenarios, separately or in combination. Likewise, a laboratory aging method that combines wetting (from one or both sides of the dressing) with sustained or repetitive mechanical loading of the dressing, including friction‐inducing shear to simulate rubbing of the dressing on the bed surface, may be applied in future work to enhance the realism of the simulated use of dressings even further.

To conclude, this is the first study ever to systematically compare the biomechanical efficacies of two inherently different dressing technologies in preventative use: A new fluff‐core based (RSB) dressing technology, against the mainstream silicone‐foam dressings. A sophisticated and rigorous experimental‐computational analysis has been developed for this purpose, to ultimately calculate the PTODP trade‐off value between delivery of tissue protection when a dressing product is new (from the package) and its ongoing protective efficacy, when that product absorbs moisture over time. The RSB dressing achieved that best trade‐off between performances of the 'new' and 'used' product, that is, a greater PTODP score than those of silicone‐foam dressings in the majority of cases. Our present results further indicated that if replaced frequently (so that it stays relatively dry), the RSB dressing will have superior biomechanical protective efficacy (PEI) over silicone‐foam dressings. Future research should explore the thermal performances of RSB dressings and of course, quantify their treatment performances as well.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by an unrestricted educational grant from Paul Hartmann AG (Heidenheim, Germany).

Gefen A, Krämer M, Brehm M, Burckardt S. The biomechanical efficacy of a dressing with a soft cellulose fluff core in prophylactic use. Int Wound J. 2020;17:1968–1985. 10.1111/iwj.13489

Endnotes

The angle between the tangent line to the superior endplate of the S1 vertebra and the horizontal plane.

The angle between the vertical plane and the tangential line to the sacral dorsum.

The static COF corresponds to the maximum torque that must be overcome to initiate motion between the fixed and rotating parts of the tribometer.

Since only the mattress‐facing surface (“backing film”) of the dressings was moistened and the backing film of the RSB dressing is made of polyurethane (PU) film which is waterproof, that is, no liquid could be transported through the backing film into the fluff core of the RSB (with the embedded superabsorbent particles there), the stiffening of the moist RSB dressing with respect to its dry behaviour (Figure 2) is likely due to swelling of the PU backing film itself.

A COF of the backing film which is too low may contribute to migration of patients in their bed and thereby, to an increase in the tissue shearing levels at body regions not protected by the dressing, 38 for example, when the heels, not protected by dressings, slide towards the foot of the bed.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data available on request from the authors.

REFERENCES

- 1. Padula WV, Delarmente BA. The national cost of hospital‐acquired pressure injuries in the United States. Int Wound J. 2019;16(3):634‐640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gefen A, Brienza D, Edsberg L, Milton W, Murphy C, Oomens CWJ, Perry L, Sari Y. The etiology of pressure injuries. In: Prevention and Treatment of Pressure Ulcers/Injuries: Clinical Practice Guideline European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (EPUAP), National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel (NPIAP) and the Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance (PPPIA), 3rd Ed; 2019.

- 3. Gefen A, Alves P, Ciprandi G, et al. Device‐related pressure ulcers: SECURE prevention. J Wound Care. 2020;29(Sup2a):S1‐S52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fulbrook P, Mbuzi V, Miles S. Effectiveness of prophylactic sacral protective dressings to prevent pressure injury: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2019;100:103400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hahnel E, El Genedy M, Tomova‐Simitchieva T, et al. The effectiveness of two silicone dressings for sacral and heel pressure ulcer prevention compared with no dressings in high‐risk intensive care unit patients: a randomized controlled parallel‐group trial published online ahead of print. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:256‐264. 10.1111/bjd.18621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel and Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance . Prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers/injuries: clinical practice guideline. Westford, MA: The International Guideline; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Burton JN, Fredrickson AG, Capunay C, et al. New clinically relevant method to evaluate the life span of prophylactic sacral dressings. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2019;32(7S Suppl 1):S14‐S20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Padula WV. Effectiveness and value of prophylactic 5‐layer foam sacral dressings to prevent hospital‐acquired pressure injuries in acute care hospitals: an observational cohort study. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2017;44(5):413‐419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Burton JN, Fredrickson AG, Capunay C, et al. Measuring tensile strength to better establish protective capacity of sacral prophylactic dressings over 7 days of laboratory aging. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2019;32(7S Suppl 1):S21‐S27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gefen A, Kottner J, Santamaria N. Clinical and biomechanical perspectives on pressure injury prevention research: the case of prophylactic dressings. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2016;38:29‐34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gefen A, Santamaria N, Creehan S, Black J. Extrapolation of evidence‐related to dressings for pressure ulcer prevention may compromise patient safety. Wounds Int. 2018;9(2):7‐15. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gefen A, Peko Cohen L, Amrani G, Hoffer O, Ovadia‐Blechman Z. The roles of infrared thermography in pressure ulcer research with focus on skin microclimate induced by medical devices and prophylactic dressings. Wounds Int. 2019;10(1):8‐15. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Levy A, Frank MB, Gefen A. The biomechanical efficacy of dressings in preventing heel ulcers. J Tissue Viability. 2015;24(1):1‐11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Levy A, Gefen A. Assessment of the biomechanical effects of prophylactic sacral dressings on tissue loads: a computational modeling analysis. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2017;63(10):48‐55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schwartz D, Levy A, Gefen A. A computer modeling study to assess the durability of prophylactic dressings subjected to moisture in biomechanical pressure injury prevention. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2018;64(7):18‐26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schwartz D, Magen YK, Levy A, Gefen A. Effects of humidity on skin friction against medical textiles as related to prevention of pressure injuries. Int Wound J. 2018;15(6):866‐874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schwartz D, Gefen A. The biomechanical protective effects of a treatment dressing on the soft tissues surrounding a non‐offloaded sacral pressure ulcer. Int Wound J. 2019;16(3):684‐695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schwartz D, Gefen A. An integrated experimental‐computational study of the microclimate under dressings applied to intact weight‐bearing skin. Int Wound J. 2020;17(3):562‐577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kottner J, Black J, Call E, Gefen A, Santamaria N. Microclimate: a critical review in the context of pressure ulcer prevention. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2018;59:62‐70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Levy A, Schwartz D, Gefen A. The contribution of a directional preference of stiffness to the efficacy of prophylactic sacral dressings in protecting healthy and diabetic tissues from pressure injury: computational modelling studies. Int Wound J. 2017;14(6):1370‐1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Forman DE, Berman AD, McCabe CH, Baim DS, Wei JY. PTCA in the elderly: the "young‐old" versus the "old‐old". J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40(1):19‐22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Linder‐Ganz E, Shabshin N, Itzchak Y, Gefen A. Assessment of mechanical conditions in sub‐dermal tissues during sitting: a combined experimental‐MRI and finite element approach. J Biomech. 2007;40(7):1443‐1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Linder‐Ganz E, Shabshin N, Itzchak Y, Yizhar Z, Siev‐Ner I, Gefen A. Strains and stresses in sub‐dermal tissues of the buttocks are greater in paraplegics than in healthy during sitting. J Biomech. 2008;41(3):567‐580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shoham N, Levy A, Shabshin N, Benayahu D, Gefen A. A multiscale modeling framework for studying the mechanobiology of sarcopenic obesity. Biomech Model Mechanobiol. 2017;16(1):275‐295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]