Abstract

An optimal position of the patient during operation may require a compromise between the best position for surgical access and the position a patient and his or her tissues can tolerate without sustaining injury. This scoping review analysed the existing, contemporary evidence regarding surgical positioning‐related tissue damage risks, from both biomechanical and clinical perspectives, focusing on the challenges in preventing tissue damage in the constraining operating room environment, which does not allow repositioning and limits the use of dynamic or thick and soft support surfaces. Deep and multidisciplinary aetiological understanding is required for effective prevention of intraoperatively acquired tissue damage, primarily including pressure ulcers (injuries) and neural injuries. Lack of such understanding typically leads to misconceptions and increased risk to patients. This article therefore provides a comprehensive aetiological description concerning the types of potential tissue damage, vulnerable anatomical locations, the risk factors specific to the operative setting (eg, the effects of anaesthetics and instruments), the complex interactions between the tissue damage risk and the pathophysiology of the surgery itself (eg, the inflammatory response to the surgical incisions), risk assessments for surgical patients and their limitations, and available (including emerging) technologies for positioning. The present multidisciplinary and integrated approach, which holistically joins the bioengineering and clinical perspectives, is unique to this work and has not been taken before. Close collaboration between bioengineers and clinicians, such as demonstrated here, is required to revisit the design of operating tables, support surfaces for surgery, surgical instruments for patient stabilisation, and for surgical access. Each type of equipment and its combined use should be evaluated and improved where needed with regard to the two major threats to tissue health in the operative setting: pressure ulcers and neural damage.

Keywords: neural damage, pressure injury, pressure ulcer, surgery

1. INTRODUCTION

Surgical positioning is a sub‐specialty of surgery that involves management of patient risks by the surgeon, anaesthesiologist, and nurse because of the combined effects of anaesthesia, trauma, blood loss, immobility, and the insensate episode during operation and early recovery. The optimal position of the patient may require a compromise between the best position for surgical access and the position a patient and his or her tissues can tolerate without sustaining injury. This article is the first scoping review on the topic and is aimed at identifying and mapping the available evidence on surgical positioning‐related tissue damage risks, the biomechanical and clinical considerations in confronting these risks, and key principles for the prevention of potential intraoperatively acquired tissue damage based on pathophysiological understanding. In addition, this article has identified and analysed knowledge gaps and some clinical practices that do not conform with relevant state‐of‐the‐art aetiological research.

We followed the scoping review methodology recommended by Levac et al 1 and Sucharew et al. 2 Accordingly, our research question was: What is the evidence published from 1990 onwards regarding surgical positioning‐related tissue damage risks and their mitigation? The databases scanned were PubMed/Medline, Cochrane Library, Scopus, Google Scholar, and the Web of Science. We considered peer‐reviewed original research articles, literature reviews, evidence synthesis, systematic reviews, meta‐analyses, scoping reviews, narrative reviews, critical reviews, chapters in books, and formal publications of professional medical societies. Conference proceedings, meeting abstracts, and posters were not incorporated. The populations of interest were adults who underwent any type of surgical intervention. We excluded non‐English publications and literature published over 30 years ago. We used an iterative process to identify the key search terms, initially using the keywords: position*, intraoperative*, perioperative*, postoperative*, operation, operating, room, table, pressure, neural, nerve, injury, injuries, ulcer*, damage, skin, tissue, surgical, surgery, procedure*, hospital acquired, prevent*, protect*, prophylactic, prophylaxis. All articles retrieved were screened for their titles, abstracts, and index terms.

2. COMMON SURGICAL POSITIONS AND MEDICAL CONSIDERATIONS FOR THEIR SELECTION

Surgical positioning is the practice of placing a patient in a specific physical position during the operation so that the vital functions and safety of the anaesthetised patient are maintained while allowing the best access to the surgical site for the surgeon. 3 Both general and neuraxial anaesthesia can affect cardiovascular stability and alter ventilation and perfusion, which can result in hypoxaemia. In addition, compression of tissue or vascular structures related to positioning can cause regional ischaemia or direct nerve injury. When these medical considerations have been met, the challenge is often to prevent tissue damage resulting from the sustained tissue deformations in the immobile and insensate patient. The focus of this article is on the prevention of tissue damage because of sustained tissue deformations in surgical patients.

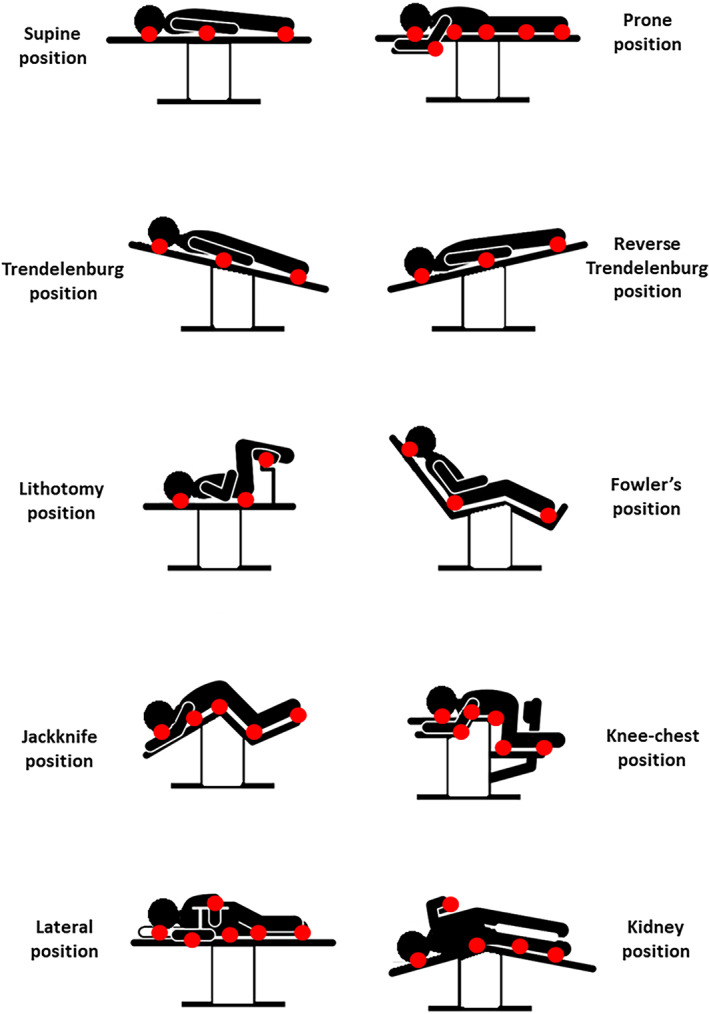

Multiple different surgical positions are used in practice (Figure 1); however, the primary ones are supine, lithotomy, sitting, prone, and lateral positions on the operating table (OT). The most common position used is the supine position. 4 Abdominal, cardiac, vascular, and lower leg operations and minimally invasive procedures are conducted in the supine position. Variants of the supine position exist, such as the Trendelenburg position where the head and upper torso of a patient are lowered below the height of their feet, for patients who develop hypovolaemic shock or to provide additional visualisation of the lower abdomen and pelvis. This position creates pressure on the buttocks or sacrum, heel, and the occiput. When gel rolls are used to hyperextend the neck for access to the chest, pressure ulcers (PUs) can develop from the rolls.

FIGURE 1.

Diagrams of the common surgical positions discussed here and the typical pressure points associated with each of these positions (marked as red circles)

Patients undergoing robotic‐assisted surgical procedures are often placed in the Reverse Trendelenburg position where the patient is supine, and the head is elevated with the feet down. This position is used in head and neck procedures or to provide better visualisation in laparoscopic procedures in the upper abdomen. Both the Trendelenburg and the Reverse Trendelenburg positions cause intensified frictional forces and elevated soft tissue distortions in shear under the scapulae (shoulders), sacrum, and calcanei (heels) as gravity pulls the tilted patient body downward, similar to migration in bed. 5

Another common variant of the supine position is the lithotomy position, which is used for gynaecological, rectal/anal, and urological procedures. In the lithotomy position, the upper torso is placed in the supine position, and the legs are raised and secured. Pressure is focussed on the lower buttocks and peroneal nerves in the lithotomy position, especially if the leg stirrups do not fully support the weight of the legs.

Other variants are the sitting positions: the Fowler (also known as beach‐chair) and semi‐Fowler (also termed semi‐sitting or lawn‐chair) positions, where the patient is supine, but then, the upper torso is raised to a 90° position (for a full‐Fowler) or less (semi‐Fowler). The Fowler position is used for shoulder surgeries or in breast surgery, where the patient is being brought to a sitting position during surgery to assess the symmetry of the breasts. The semi‐Fowler position is used in nasopharyngeal, facial, neck, and breast surgeries and some abdominal cases.

Anatomical sites where sustained and elevated pressure and shear may apply to soft tissues in the above group of supine positions are the occiput; the scapulae; along the spine; and at the elbows, sacrum, and heels. The neural structures that could be potentially affected by these sustained tissue deformations are the brachial plexus and the radial, ulnar, median, common peroneal and tibial nerves. In the supine and lithotomy variants, elevated pressure and shear may also develop at the femoral epicondyles, tibial condyles, and lateral and medial malleoli, depending on the specific method of leg securement. In Fowler and semi‐Flower positions, shear is also increased because of gravity acting on the head and trunk mass.

Another group of common surgical positions is the prone positions, with the abdomen supported or raised off the OT. Prone surgical positioning is used to operate the posterior brain, spine, rectum, and the posterior aspects of the extremities, such as in Achilles tendon repair. Important to the discussion of PU or pressure injury prevention (the term “pressure injury” has replaced the term PU in several English‐speaking countries, that is, the United States, Canada, and Australia), the prone position is used for surgical repair of sacral and ischial PUs. Here, as well, different variants exist, such as the jackknife (also called the Kraske) position, in which the abdomen lies flat on the OT, which is then folded so the hip is lifted and the legs and head are lowered, which allows surgical access to the rectum. Another variant is the knee‐chest position, which is similar to the jackknife, except that the legs are bent 90° at the knee. Anatomical sites that are often subjected to sustained pressure and shear in the group of prone surgical positions are facial tissue structures such as the forehead and chin, the eyes and the nose, the breasts, the genitalia, and tissues over bony prominences.

Another common group of surgical positions is the lateral decubitus positions, where a patient is positioned on their side, to allow access to, for example, the lungs, posterior thorax, kidneys, retroperitoneal space, and hips. Variants are, for example, the “kidney position”, where the abdomen is placed over a lift in the OT, which bends the body to allow access to the retroperitoneal space. Another variant of the lateral position is Sims' position, in which the patient is lying almost prone, with the knee of the upper leg flexed and the lower leg straight. The eye globe and ear, which are nearer the OT, could be subjected to sustained pressure and shear in lateral surgical positions, and so, surgical guidelines highlight that the ear must lie flat and the eyelid must be closed during such surgeries. In fluoroscopically assisted hip fracture repair, the upper torso is in the supine position with the unaffected leg raised (knee flexed), whereas the affected leg is extended with no lower support and strapped at the ankle for traction. A perineal post is also used in these procedures to prevent the patient from sliding when traction is applied to the fractured leg during reduction.

3. PREVALENCE AND RISK FACTORS FOR INTRAOPERATIVELY ACQUIRED TISSUE DAMAGE

3.1. Pressure ulcers/injuries

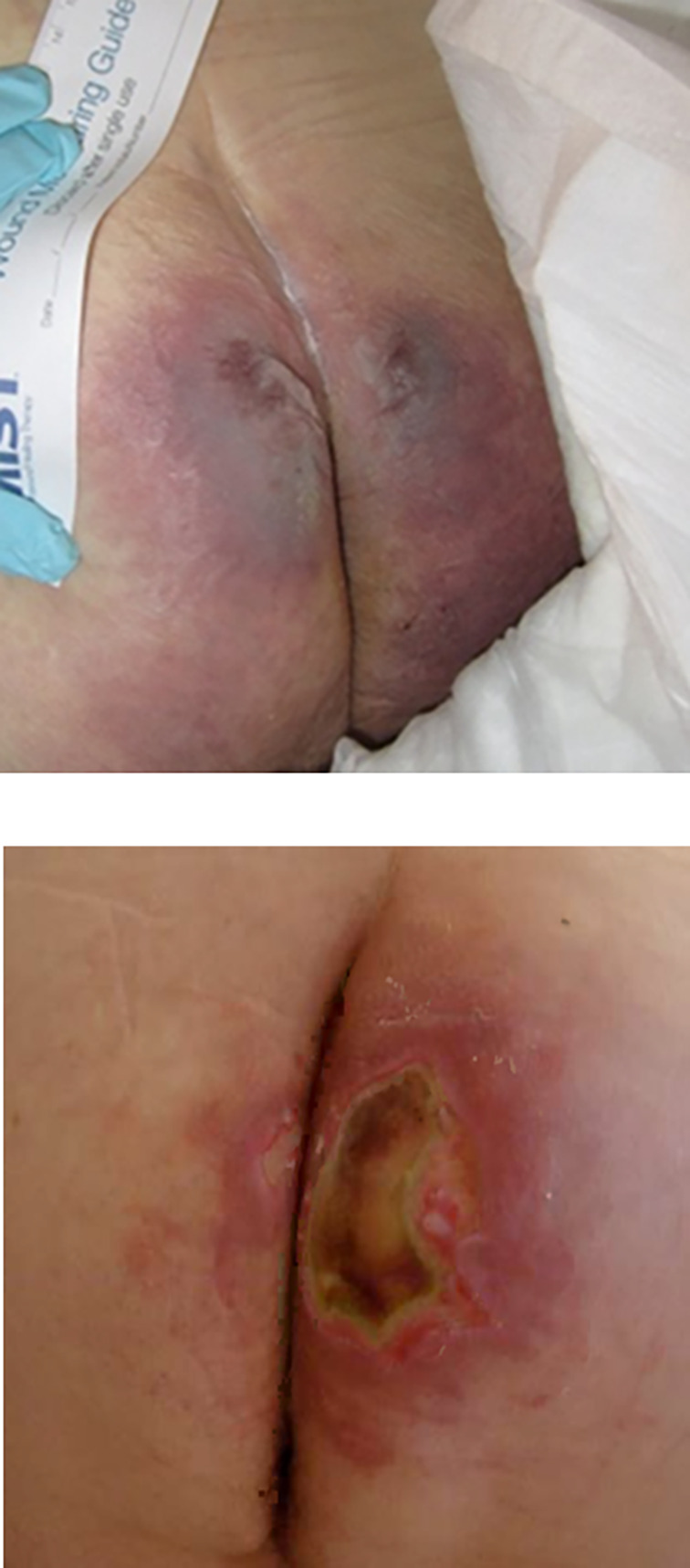

Among the different care settings associated with increased PU risk, the operating room (OR) is known to be one of the most high‐risk environments. The primary cause of PUs is sustained exposure to cell and tissue deformations. 6 Surgical patients are therefore, by definition, at a high risk for developing PUs because of the lack of sensation and immobility during the actual course of surgery and part of the recovery from the operation, 7 , 8 throughout which soft tissues at the supported body sites are distorted continuously and unrelievedly. A PU identified within 72 hours after a surgical procedure is typically considered an intraoperatively acquired injury. 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 The overall rate of these intraoperatively acquired PUs vary substantially, from 12% to 66%. 12 The prevalence of PUs among surgical patients for procedures that last longer than 3 hours is at least 8.5%. 14 PUs are a major complication of cardiovascular surgeries, which are performed in a supine position (Figures 2 and 3); these injuries occur in 9.2% to 38% of the patients. 15 In one study involving 136 adult cardiac surgery patients, approximately 27% of the participants developed category 1 to 2 PUs. 12 In a latter study of 351 cardiovascular surgical patients, 24 patients (7%) had tissue breakdown. 15 Breakdown by categories was as follows: category 1, 62% (n = 15); category 2, 29% (n = 7); category 3, 4% (n = 1); and category 4, 4% (n = 1). 15 Orthopaedic surgical patients are also susceptible to intraoperative PUs. In a study analysing data from spinal disc herniation repair and abdominal surgeries in 24 patients, 9 (36%) developed category 1/2 PUs. 16 Among a cohort of geriatric hip fracture repair patients, 457 of the 8871 subjects (5.2%) developed PUs. 17 In liver resection patients, 11 of 128 patients (8.6%) have been reported to develop category 1 PUs in surgeries longer than 2 hours. 18 The above‐reported variation in prevalence rates reflects marked differences in biomechanical tissue conditions at the various surgical positions and use of different equipment such as OT pads and other positioning and restraining devices, as well as variable patient conditions, ages, and health status.

FIGURE 2.

Intraoperatively acquired pressure ulcers/injuries developed during supine surgery

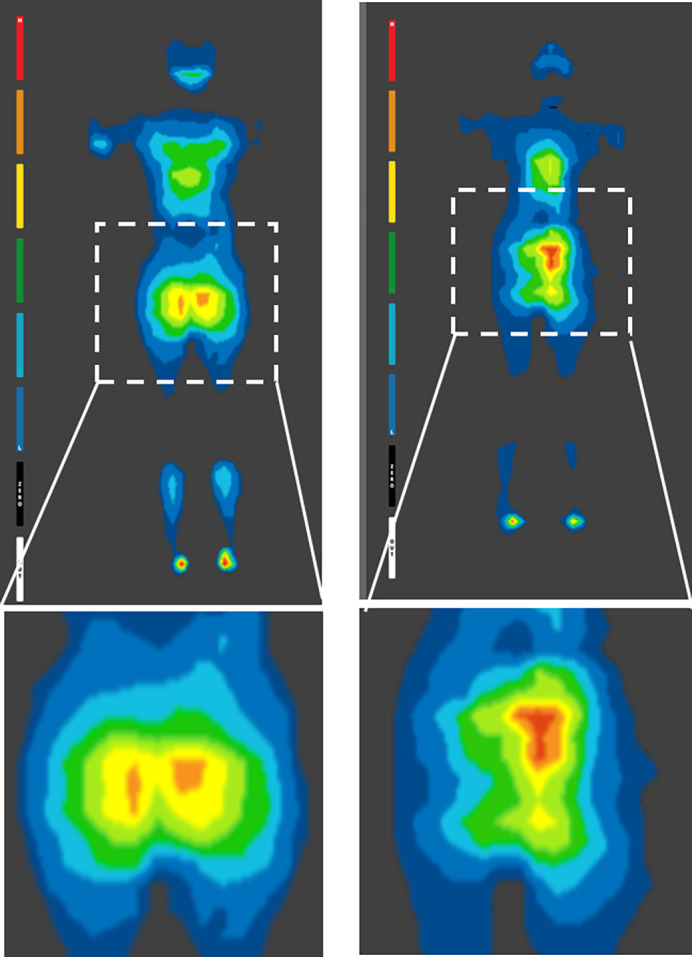

FIGURE 3.

Examples of interface pressure mapping during supine and planed surgical positions, acquired on operation tables with surgical pads. High‐pressure sites are coloured red. These high‐pressure “hotspots” are shown near the sacrum for both the female (left frames) and male (right frames) patients. The respective high sacral pressure regions have been magnified for clarity for both subjects (bottom frames)

The surgical positioning and anaesthetic agents introduce specific risk factors that are added to the common risk factors for PUs. Surgical positioning (as reviewed above) may cause unusual localised deformations and stress concentrations in soft tissues; however, repositioning during surgery is unfeasible. For example, the park‐bench position, a modification of the lateral position to provide better surgical access to the posterior fossa in the skull, has been identified as bearing a high risk for intraoperative pressure ulceration, particularly if the surgery lasts for more than 6 hours. 19 , 20 The aforementioned 2016 Japanese study reported intraoperative PUs in 11% of the study population (30 of 277 patients).

In addition, the blood loss, resulting in lower arterial pressures, and the lower body temperature, causing vasoconstriction, both contribute to a reduced tissue perfusion, which increases the susceptibility to ischaemic tissue damage that is derived from the sustained tissue deformation exposures. 6 Moreover, intraoperatively, where prolonged hypotension episodes are observed, catecholaminergic vasopressors (eg, norepinephrine, epinephrine, or dopamine) may be administrated to increase the arterial pressure, but at the tissue microscale, vasoconstricting agents may in fact constrict arterioles and reduce microvascular perfusion and, thereby, decrease the physiological heat convection, particularly to the periphery. 21 A drop of 1.8°C in the core body temperature, which is common in surgical patients, 14 , 19 increases the odds of pressure ulceration by approximately 20%. 22 Yoshimura et al 19 further reported that excessive perspiration and body temperature above 38.1°C were risk factors in the park‐bench position.

Another relevant point to consider in the context of risk is that surgical positioning is combined with use of specific surgical (eg, retractors) and life‐support instrumentation (such as endotracheal tubes and intravenous lines) that may induce additional localised compressive and shear forces on the surface of the body.

It is also worth noting that tissue exposures to sustained loading during an operation cannot be examined apart from the events that preceded surgery. Some patients are admitted through the emergency department (ED) or have undergone an interventional procedure prior to their operation (eg, cardiac catheterisation or interventional radiological or endoscopy procedures). Hence, a PU could have formed already in the ED or during the prior procedure (especially if patients were also unconscious or chemically sedated preoperatively). The preoperative history of exposure to pressure and shear should therefore be considered in conjunction with the above other OR‐specific risk factors.

The work of Hayes et al 23 to determine the relationship between time on the OT and 931 pressure ulceration cases confirmed that surgery over 4 hours is a risk factor for PU development; however, they reported that only 5% of the injuries occurred within 24 hours of surgery, whereas 58% occurred after the fifth hospital day. Nevertheless, considering that some of the injuries identified in the days after the operation began as deep tissue injuries (DTIs) under intact skin, the above finding very likely represents a clinical challenge in the diagnosis of sub‐surface tissue damage rather than a belated development of these wounds. Their conclusion that “most pressure ulcers do not appear in the immediate postoperative period” suggests that, indeed, a significant portion of the intraoperative PU cases are DTIs that present themselves (ie, progress to skin lesions) later in the time following surgery. This understanding drives contemporary research work, such as that of Grap et al, 24 who conducted high‐frequency ultrasound examinations to detect DTIs that formed during surgeries. Their work confirmed that structural changes in subdermal tissues can precede the clinical appearance of intraoperative injuries in visual skin assessments. 24

3.2. Intraoperatively acquired nerve injuries, nerve ischaemia, and palsy

Localised, elevated, and sustained tissue deformations occurring in one of the above‐described surgical positions may also lead to nerve injuries, which affect sensory or motor pathways. Damage to sensory nerves can cause numbness, sensations of pins and needles, continuous ache, sharp shooting pain, or inappropriate warm or cold sensations. Damage to motor nerves leads to weakness or paralysis of the innervated muscles. Postoperative brachial plexopathy and other peripheral nerve injuries because of direct nerve distortions, obstructed intra‐neural blood vessels, or a combination of both are common. A recent review of postoperative brachial plexus injuries identified 17 brachial plexopathy cases of 517 patients who underwent spine surgery in the prone position. 25 Use of chest rolls for the prone positioning and an unsupported head, together with the low muscle tone because of anaesthesia, may result in posterior shoulder extension and anterior head displacement, thereby leading to brachial plexopathy. 26 Lateral femoral cutaneous nerve neuropathy has been reported from direct compression by bodyweight forces, with an incidence as high as 24% post‐spinal surgery. 27 The incidence in a general population of surgical patients undergoing all types of procedures is 0.03 to 1.5%, 28 with greater incidence rates in cardiac, neurosurgery, and orthopaedic procedures. 29 , 30 Permanent neurological injury has an incidence rate of 2.4 in 10 000 peripheral nerve blocks. 28 The literature reflects that prone positioning imposes a greater risk for neural damage. 31 Intraoperative peripheral neural injuries represent 12% of the general anaesthesia malpractice claims since 1990, with injuries to the brachial plexus and ulnar nerves representing two‐thirds of these claims. 29 Direct pressures on the eyes, especially as a result of a patient malposition on the OT, has been cited as a factor contributing to visual loss, often irreversible. 32

Like PUs, the likelihood of neural injuries increases with the length of the operation, particularly for procedures longer than 3.5 hours. 33 Nevertheless, biomechanical laboratory work indicates that even short durations of sustained loading of nerves, in the order of tens of minutes, are sufficient to cause permanent damage. Nerves may be damaged when stretched or compressed even minimally. Adverse electrophysiological changes in nerve function precede structural damage to perineural sheaths. 34 In a rabbit model, the conductivity of tibial nerves subjected to 6% stretch for an hour was reduced by 40% whereas 12% deformation resulted in nearly complete nerve blockage, which was not fully recovered even an hour after unloading. 35 Accordingly, and as in the case of PUs, minimising the intensity of and time exposure to tissue deformations through appropriate positioning equipment directly minimises the risk of intraoperative nerve injuries.

3.3. Postoperative joint and muscle pain

Other than the pain caused directly by surgical incisions and the related tissue damage, neck and back pain, joint pain, and muscle pain (myalgia) associated with positioning on the OT are common. The latter type, myalgia, has often been attributed to the use of the skeletal muscle relaxant drug succinylcholine (“scoline”), used for endotracheal intubation; however, some patients experience myalgia even when they are not given succinylcholine, which is reflected in the highly variable reported incidence range of myalgia, that is, from 1.5 to 89%. 36 Another relaxant drug, rocuronium, has been said to decrease fasciculation and myalgia following succinylcholine administration, 37 but the mechanisms of action remain unclear. The duration of the myalgia also varies, usually lasting 2 to 3 days but sometimes even a week. 36 Postoperative joint pain is induced by activation of joint nociceptors because of sustained pressures on the immobilised joint. Similarly, muscle pain can be explained by the continuous skeletal muscle deformations caused by the bodyweight forces; however, in the case of muscle tissue, this is combined with spikes of dynamic intra‐muscular shearing forces because of fasciculations that are generated by the drug. 38 The intensity and distribution of muscle tissue loads generated by these complex biomechanical interactions depends on the individual anatomy, body habitus, and soft tissue composition and also on the severity of the fasciculations caused by succinylcholine. The multifactorial contributions to the muscle tissue loading state explain the aforementioned variable incidence of myalgia across patients. It is worth noting that electromyography studies of succinylcholine‐induced fasciculations suggested the development of muscle micro‐damage. 39 The specific postulated mechanisms for such cell‐scale damage may include increased intra‐cellular calcium concentrations, membrane phospholipid degradation, and release of free fatty acids and free radicals, which altogether lead to increased plasma membrane permeability that compromises cell viability. 40 The resulting cell death will likely lead to a localised inflammatory response (already during the course of surgery for procedures that last several hours). Given that muscle nociceptor neurons, which are responsible for transmitting pain stimuli to the central nervous system, possess receptors and ion channels that detect the molecular mediators released during inflammatory events, muscle pain is likely to follow. 41 , 42 Interestingly, the muscle nociceptors are also sensitive to an acidic pH, 42 which develops in ischaemic tissue conditions, and hence, the hypotension induced during surgery (discussed in detail below—see effects of anaesthetics) may exacerbate the nociceptor firing and, accordingly, the intensity of muscle pain that a patient experiences postoperatively. In this context, the study of Power 43 confirmed that the likelihood of postoperative muscle or joint pain, distinctive from the incisional site pain, depends on the length of the operation. Of the 41% (n = 63 of total study participants N = 153) of women who underwent gynaecological surgery and reported postoperative lower extremity pain (separate from the incisional site pain), those who were in position for more than 1 hour had significantly more pain than those who were in position for less than an hour. The impact of myalgia on the tolerance of the patient for repositioning after surgery is unknown.

3.4. In‐depth analysis of known risk factors

3.4.1. Operation and recovery times

The duration of the surgery, calculated from the time taken into the OR until the time out of the OR, is known to be a major risk factor for pressure ulceration. In practice, even a 2‐hour (net) surgery can imply 6 or more hours of immobility for the patient. The literature indicates a growing PU incidence rate with the time on the OT, which is approximately 6% for 3‐ to 4‐hour operations, 9% for 4‐ to 5‐hour procedures, 10% for 5‐ to 7‐hour surgeries, and over 13% for operations lasting more than 7 hours. 44 , 45 , 46 Hence, any procedure lasting more than 2 hours should be considered imposing a high PU risk, and that risk increases further with additional time on the OT. To confirm this, Schoonhoven et al 47 conducted a carefully designed clinical study involving 208 patients who had operations that were longer than 4 hours. They chose this length of surgery based on the common practice of repositioning non‐surgical patients every 2 to 3 hours to prevent PU formation, interpreting this as indication that the likelihood of injury in shorter surgeries would be small. Forty‐four patients (21.2%) developed 70 PUs in their cohort, which were diagnosed in the first 2 days post‐operation; 21 of these wounds deteriorated thereafter and have caused disability in 25 (12%) of the studied patients. More than half (52.9%) of the PUs in the Schoonhoven 47 study were heel injuries, whereas 15.7% were sacral wounds. Importantly, Schoonhoven et al 47 found that, with every 30 minutes after 4 hours of surgery, the PU risk increased by 33%. It is worth noting that the PU risk continues to apply even after a patient is out of the OR, during recovery from the anaesthesia, where the sedated patient still did not gain normal sensitivity and movement capacity.

3.4.2. Effects of anaesthetics

Anaesthetic and sedative agents used in surgery lower the blood pressure (combined with intraoperative blood loss), cause peripheral hypo‐perfusion (which affects tissue metabolism), and clearly neutralise the pain response. It is not surprising therefore that general anaesthesia is associated with greater PU incidence than use of regional anaesthetics. Fife and Gkotsoulias 48 recently suggested that intraoperative positioning along with permissive hypotension may decrease arterial or venous flow to angiosomes (areas of skin and underlying tissues vascularised by a source artery), causing an ischaemia‐reperfusion injury to the downstream tissues in body peripheries such as the heels. Permissive hypotension has replaced the classic aggressive fluid resuscitation aimed at maintaining normotension during surgery to not compromise the function of coagulation factors. Yet, diastolic blood pressures lower than 60 mm Hg and hypotensive events are known to contribute to the pressure ulceration risk, likely because of the aforementioned ischaemia‐reperfusion damage mechanism. 9 Therefore, the hypotension caused by general anaesthesia and further supported by permissive hypotension protocols (which may not balance the anaesthesia‐induced hypotension by means of intravenous fluids or vasopressors) appears to increase the risk for intraoperative PUs.

3.4.3. Instruments and set‐ups used for the surgical purpose

The OT is the primary equipment used for positioning. It enables bending so that patients can sit up or accommodates flexion of their knees. Arm boards are added for positioning of the arms to avoid brachial plexus injury, and other parts of the OT can be removed to allow the surgeon to access the surgical site. 49 Lateral tilting (called planing, akin to banking an airplane) the OT is often required during various procedures, and many OTs allow for a lateral tilt of up to 30° to facilitate better surgical access, 50 at the price of increasing the bodyweight‐caused shearing forces and tissue distortions on the dependent body area (often the lower buttock cheek).

The standard OT has a thin mattress (pad) made of foam or gel, which makes a relatively hard surface. Foam OT pads are common; they are composed of a 2‐in. to 5‐in. elastic foam covered with black, conductive, laminated vinyl fabric. The thinner OT pads allow x‐rays to be taken during surgery without obscuring the radiographs. While OT pads provide good stability, Scott 51 cited several studies which demonstrated that thinner OT pads contribute to intraoperative PU development. This is because OT pads must be made of relatively stiff foam materials 52 to prevent bottoming out, which implies that bodyweight forces have to be distributed over smaller contact areas. The transfer of the bodyweight forces through smaller contact areas results in greater peak interface pressures and localised shear forces 53 and, therefore, greater tissue deformations compared with those that form when the same individual lies on a thick and softer foam mattress of a hospital bed. To address this problem, new technologies use a thin alternating pressure overlay 54 , 55 , 56 or an automatically adjustable mattress with an air‐cell structure to minimise tissue deformations through immersion and envelopment. 57

There are various fittings and accessories for patient positioning on the OT, including gel pads, head rests (eg, cushions, donut‐shaped off‐loading cushions), shoulder braces, and body‐restraining straps that are used to prevent falling of patients from the OT. 49 , 58 Posts may be used instead of strapping, or in addition to strapping, in order to prevent falls, which are a major source of concern and have been reported to cause death in the OR. 50 Nevertheless, use of posts implies localised contact between the body of the patient at each post, which may induce tissue stress concentrations at and near the body‐post contact sites, particularly if the OT is tilted (which is when the use of such posts is recommended. 50 ) A peroneal post is a common example, which is used to prevent movement of the patient during traction on the leg during hip pinning. However, even if the post is well padded, bruising and hematoma of the perineum often follow. Stirrups are also commonly used for anal, perineal, or gynaecological procedures. Use of a single stirrup is further possible, for example, in knee arthroscopy where flexion provides better access to the joint. 59 Stirrups, like posts, provide limited body‐device contact area sizes, which lead to tissue stress concentrations.

Patients undergoing general anaesthesia are at increased risk of hypothermia because of inhibition of thermoregulatory control, increased heat loss to the environment, and absent behavioural responses. Heating pads and warming devices can be placed under or above the patient to reduce the risk of surgical hypothermia. Grous et al, 60 Scott et al, 46 Feuchtinger et al, 61 and Aronovitch 9 all indicated that the use of warming devices under the patient on standard OT mattresses increases the risk of PU development. One explanation for this is the combined sustained elevated tissue deformations and the increased metabolic demand of the heated tissues; a 1°C rise in skin temperature causes a 10% increase in tissue metabolism. 46 , 62 However, the additional reason for the increased PU risk on the warming devices is that they compromise the immersion and envelopment of the patient body by the surgical support surface. Hence, Grous et al 60 specifically recommended removal of the warming blanket from routine intraoperative use for patients undergoing prolonged operations. Forced‐air convective warming systems are commonly used today. Fred et al 22 studied intraoperative PU formation and intraoperative hypothermia and reported that those with a 1°C drop in body temperature were at higher risk of PU formation. Other devices that may be associated with PU development for similar reasons include pillows, blankets, gel, and foam pads used for cushioning without fitting that tissue protection purpose.

3.4.4. The acute inflammatory response to surgical wounds

Surgical incisions are, by definition, soft tissue injury and, as such, will activate the inflammatory system. Loram et al 63 characterised the time course of inflammatory cytokine release at the site of injury and in plasma after surgery on the rat tail and found that the inflammatory mediator concentrations of interleukin‐1β (IL‐1β), interleukin‐6 (IL‐6), tumour necrosis factor‐α (TNF‐α), and cytokine‐induced neutrophil chemoattractant‐1 (CINC‐1) in tissues increase after only 2 hours. Concentrations of IL‐1β, IL‐6, and CINC‐1 continue to grow within 24 hours post‐surgery, and TNF‐α levels further increase during the first 48 postoperative hours. These inflammatory mediators cause vasodilation and increase the local vascular permeability by affecting endothelial cell‐to‐cell junctions, 64 , 65 which leads to localised oedema. This implies that, if the operation lasts for longer than 2 hours, oedema begins to develop already during the intraoperative period. The forming oedema gradually increases the interstitial fluid pressures in tissue structures adjacent to the surgical site, which are confined between the OT and bony prominences. The rise in interstitial tissue pressures causes further cell distortion and promotes additional soft tissue stress concentrations because of the localised increase in tissue stiffness, 66 which adds to the already existing tissue deformations and stresses caused by the sustained bodyweight forces. Hence, the inflammatory response to surgery (already during the actual course of surgery) contributes to worsening the tissue loading state, which increases the likelihood of intraoperative tissue damage in forms of PUs and peripheral neural lesions.

3.4.5. The vascular perfusion and the effects of inotropes/vasopressors

Potent vasoconstrictors are commonly administered to critically ill and surgical patients to elevate mean arterial pressure. Vasopressors are considered to be first‐line drugs in the treatment of shock states 106 but have been associated with PU development, particularly norepinephrine. 67 Cox and Roche 68 reported that cases of administration of norepinephrine or vasopressin, where the mean arterial pressure dropped below 60 mm Hg or after a cardiac arrest, were significantly correlated with a later pressure ulceration. These authors also noted that vasopressors are life‐saving in such conditions, and so, the aforementioned risk of ischemia‐reperfusion tissue damage is considered, perhaps leading to an unavoidable PU afterwards.

3.5. Risk assessment tools for surgical patients and relevance to positioning

Although surgical patients have a high risk of tissue damage development, well‐documented risk factors such as predicted time on the OT are missing in conventional risk assessment tools such as the Norton, Waterlow or Braden scales. 45 A meta‐analysis of the Braden Scale for predicting PU development in the OR found low values (sensitivity = 0.42, specificity 0.84, ROC = .6921). 69 Moreover, responsibility for intraoperatively acquired PUs are often incorrectly blamed on other, postoperative care settings, which results from the natural pathophysiological cascade of progression of the injury, that is, the delay of PU demarcation on the skin. 45

Specific PU risk assessment scoring systems have been developed for use in the OR and have been evaluated based on sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values. The Munro Scale 110 was proposed by the Association of periOperative Registered Nurses 70 based on a Delphi (expert opinion) process. The Munro Scale scores patients in three categories: preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative. The preoperative Munro indicators include mobility, nutritional status, body mass index (BMI), weight loss, age, and comorbidity. The intraoperative part includes the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status score, the type of anaesthesia, body temperature, hypotension, moisture, surface/motion, and position. The postoperative scoring criteria are the duration of the operation and extent of blood loss. The problem with the Munro scale is that it explains the risk factors for intraoperatively acquired PUs, rather than predicts them. There have been additional attempts to optimise a scoring system for surgical patients, for example, Gao et al, 71 who opted to focus on application of external forces during the operation, lean body mass, duration of the operation, prone position used for surgery, cardiopulmonary bypass during surgery, and intraoperative blood loss. Another recent effort to form an improved surgical risk assessment tool was that of Park et al, 72 who used the Scott‐Triggers tool 73 as the basis for their work. The Scott‐Triggers assessment includes age, serum albumin, ASA physical status score, and the estimated surgery time. 73 The Park 72 study enhanced this tool with several additional factors: the type of anaesthesia, laboratory test results, and comorbidity conditions. Their logistic regression model to identify significant factors showed, as expected, that, while the Braden tool cannot identify any significant factor that predicts intraoperative PUs, the Scott‐Triggers tool (with or without the additional items) does have a predictive value. The specific factors that were found to be significant were the estimated surgery time and serum albumin level. 72 Brain disease, which was not found to be significant in the “lean” Scott‐Triggers model, emerged as significant in the extended version. Another recent risk assessment tool that has demonstrated effectiveness in identifying patients who are at risk of intraoperative PUs is called the “perioperative risk assessment measure for skin” (PRAMS 74 ;). Risk indicators of interest in PRAMS include diabetes, age, surgical time, the “conventional” Braden score, previous surgery, and a pre‐existing PU. Importantly, the duration of operation appears in all the above reviewed tools and is very likely the most important factor of all. The Gao 71 work, which considered application of external forces and being in prone position, is particularly relevant in the context of the present review as they targeted relevant biomechanical factors that directly affect tissue loading states.

3.6. Assessment of preoperative and postoperative tissue conditions

The current standard of OR nursing care requires visual and tactual head‐to‐toe, front‐to‐back skin assessments (including testing of red skin areas for blanching and documentation of bogginess, scars, and warmer or cooler skin sites). This should be conducted pre‐ and postoperatively to identify intraoperatively acquired PUs. Clearly and by definition, such skin assessments, even if performed thoroughly, document already‐existing tissue damage. In particular, these skin assessments cannot detect early damage sub‐dermally or identify microscopic signs or predictors of clinically significant tissue damage. Moreover, these skin assessments are not infallible and are subject to misinterpretation, 75 particularly concerning patients with a dark skin tone. 76 Skin assessments become even more problematic given the current understanding that most of the severe PUs are in fact DTIs, which initially cannot be seen by the unaided eye of even the most skilled, experienced, and well‐trained medical practitioners. 77 In other words, diagnostic medical technology for early detection of PUs is, overall, lagging behind surgery science and technologies that currently facilitate whole‐day operations, or even longer surgeries in extreme situations. Paradoxically, nurses are expected to detect (on the skin surface) an injury that evolves sub‐dermally after such prolonged exposures to sustained bodyweight forces. This finding is only possible when the PU actually presents itself at the skin surface, which is often at a stage where substantial deep tissue necrosis has already been caused, and damage is likely irreversible. 78 Accordingly, there is a need to progress from the current traditional skin assessments to technology‐based examinations of tissue status, for example, those focusing on identifying changes in biophysical (biocapacitance) or biochemical (eg, interleukin) inflammatory markers postoperatively with respect to the preoperative basal levels 6 , 79 , 80 or impaired perfusion (thermography). 81

4. POSITIONING DEVICES THAT ARE REGULARLY USED IN THE OR

4.1. The principles of adequate positioning: A biomechanical perspective

Because it is not possible to influence the length of the surgery, and complications experienced during the operation can require additional time, prevention should primarily be aimed at decreasing pressures and shearing on the skin and soft tissues throughout the operation and postoperatively (during the recovery period) so that sustained exposures leading to soft tissue deformations and stresses are minimised. Prevention can be achieved, for example, by increasing the immersion and envelopment of the body (a) by the support surface placed on the OT; (b) by using advanced positioners that mould to the shape of the body contours, and, thereby, maximise contact areas for bodyweight force transfer locally for certain body parts; and (c) by means of prophylactic dressings, which alleviate soft tissue loads (especially shear) at selected vulnerable anatomical sites. Nonetheless, the engineering design constraints for OR support surfaces are much stricter than for other medical support surfaces intended for intensive care unit (ICU) use, or the general wards, as follows.

4.2. Specific requirements from support surfaces used in the OR

The OT is a utility table designed to facilitate surgery, not patient comfort. This purpose of the OT matches the most common OR support surface types, which are non‐powered mattresses or overlays of foams, viscoelastic polymers, gels, or a combination of these materials. 82 Advanced active support surfaces for the OR, including alternating pressure overlays 55 , 56 and active pressure redistribution systems, 57 are also available. Not surprisingly, the necessities of specific OR support surfaces contradict the basic biomechanical requirements for tissue protection from PUs and neural damage, particularly with regard to the low‐tech, non‐powered OT mattresses or overlays. First, OT mattresses and overlays (each and when applied together) need to be thin and low profile relative to support surfaces for non‐OR beds (eg, for ICUs). The thinner profile is required in the OR to allow x‐ray through the table, minimise the risk of fall from the OT, and also to form a stable surface for the surgical team to be able to work without causing the patient to wobble during surgery. Some operations require high stability of the patient's body, particularly neurological, cardiovascular, or tumour removal procedures. This stability is typically achieved on a thin surgical support surface; however, thin surfaces cannot provide necessary immersion and envelopment of the patient's body. Moreover, there is interplay between thickness and stiffness of the support surface, namely, a thinner support surface must be made of stiffer (foam, gel) materials to prevent bottoming out. Given that repositioning is not feasible for preventing PUs or neural tissue damage in the OR, and as conventional immersion and envelopment design strategies do not fit all OR settings for the above reasons, alternative and complementary means of tissue protection are specifically needed in the OR to augment the limited protection capacity of low‐tech surgical support surfaces. Such additional means may include positioners and prophylactic dressings with proven reported biomechanical efficacy, as discussed in the following sections.

4.3. The high risk from using improvised positioning by means of pillows, rolled towels, sheets, and blankets

Use of pillows, rolled towels, sheets, and blankets as positioners in the OR remains a clinical practice but is considered unsafe, not only because linen are made of flammable materials but also because these linen have not been designed for conforming to the body contours and maintaining shape thereafter and will tend to flatten under bodyweight forces. 83 Flattening or sliding off of the original position 84 slowly compromises the desired surgical position and, importantly, applies kinetic frictional forces on skin and resulting tissue distortions in shear because of the movement of the supported areas. 83 Forces applied during surgery, for example, by surgical tools, may further contribute to these sliding movements and hence to the build‐up of shear loads in soft tissues. Consistent with the above, linen layers added on top of pressure redistribution surfaces have been shown in laboratory experiments to cause increases in peak body pressure magnitudes, indicating that effective contact areas for body support are reduced by the placed linen. 85

It is worth noting that shape conformation of a positioner to the body contours preoperatively, at the time of positioning, is insufficient if there is no inherent adjustability and adaptability of the positioner structure to the intraoperative body tissue responses. 86 Such tissue responses may include potential body surface shape changes that may occur during surgery, for example, because of blood loss, fluid infusion, or blood transfusion. For example, consider a positioning device commonly referred to by clinicians as the “bean bag.” This positioning device contains numerous small beads that are arranged to conform to the shape of an extremity when negative pressure (vacuum) is applied to their container. The result is a nearly‐rigid support surface; hence, any shape irregularity in the surface of the vacuumed device itself (however small), or a change in shape of the body surface of the patient as explained above, will create high localised tissue deformations and distortions. Therefore, adequate surface matching between the body and a positioner must also be based on material flexibility of the positioner, which is required in order to compensate for and conform to local device/patient shape irregularities or changes. 86

4.4. Foam wedges and gel pads: Inexpensive but limited in protection capacity

An apparently more advanced alternative for maintaining a surgical position is to use the dedicated foam wedges and gel pads that are available in the market. Both medical foams and gels are made to be stiffer than soft body tissues 52 to allow these devices to support body parts as needed; however, that generates a material stiffness transition at the body‐contact interfaces and, thereby, focal tissue stresses. Specifically, high‐density foam materials are needed to maintain the shapes of foam wedges when these are subjected to bodyweight forces, and as the stiffness of a foam relates to the foam density according to a power law, the foam stiffnesses are in the order of 10seconds of kilopascals, 87 which is considerably stiffer than the supported soft tissue structures. 88 Indeed, foam cushions 89 , 90 and head positioners 88 have been found to provide limited immersion and envelopment, resulting in increased tissue stress concentrations under bony prominences compared with specialised surfaces such as air cell‐based or shape memory structures, which are specifically designed for maximising envelopment. In addition, fatigue mechanical and thermal loading gradually breaks struts in the microstructure of foams, which softens and reduces the elastic recoil (resilience) properties of the foam. 91 Gel materials and compartments are likewise subjected to material aging. 92 Accordingly, aged foam or gel positioners may eventually deflect to their limit, that is, bottom out during OR use. While published work exists in this regard concerning wheelchair cushions (as cited above), there are no specific reports focusing on the aging of OR foam or gel positioners, and this requires specific new research. Such additional research work should also cover the effects of cleaning and sterilisation processes (not limited to autoclaving) on the stiffness and resilience of these products.

4.5. Prophylactic dressings increase tissue protection from static friction effects

Effective prophylactic dressings protect soft tissues subjected to bodyweight and frictional forces during surgery at the anatomical sites of application (where PUs are known to occur during surgery). 93 , 94 For example, multi‐layered specialised silicone‐foam sacral and heel dressings may be applied to protect the sacrum and posterior heels during a supine surgery. Our published work reported several key design features that are essential for obtaining effective tissue protection during surgery. First, a multi‐layered alternating‐stiffness dressing structure is needed, with embedded anisotropy in the dressing; such a specific dressing structure has been shown to absorb shearing forces and therefore alleviate shear stresses in tissues. 95 , 96 , 97 Second, a minimal friction coefficient is needed at the external surface of the dressing (which is achieved through a smooth outside coating of the dressing) to further reduce frictional forces and shear distortions that are transferred to the dressing and from there to the tissues under the dressing via the patient‐support interface. Third, there should be minimal influence of fluid retention from perspiration on the mechanical behaviour of the dressing. Selection of adequate prophylactic dressings becomes particularly important in the OR settings as, again, repositioning is not feasible. Moreover, the support surface placed on the OT is thinner and stiffer than, for example, those used in ICU beds, which imposes greater sustained tissue deformations on the OT and, therefore, higher intraoperative PU, as well as neural injury risks. 52 The characteristics of a biomechanically effective prophylactic dressing have been discussed in detail in Gefen, 95 and clinical evidence for their effectiveness grows rapidly. 98 , 99 However, studies in the OR are needed.

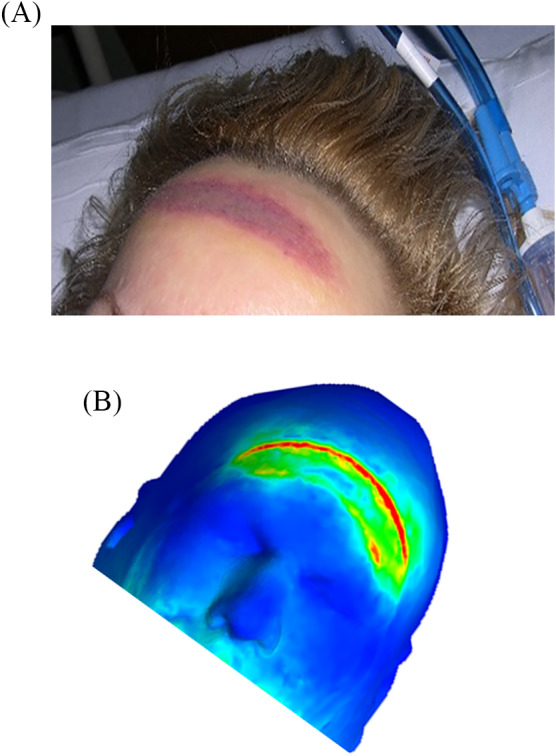

4.6. The risk to scalp tissue health when using donut‐shaped head positioners

Donut‐shaped gel head supports are still in common use for allegedly protecting the occiput during supine surgery. Katzengold and Gefen 100 recently investigated the effects of these off‐loading devices on scalp tissue loading, using three‐dimensional anatomically realistic finite element computer modelling of an adult head, which was resting on such a donut‐shaped positioner. They then compared the occipital scalp tissue loads occurring while the donut‐shaped gel head support was in use against the tissue loads that form where a standard flat medical foam cushion is placed under the (same) head. The donut‐shaped gel head support caused substantially greater exposure of scalp tissues to stresses, particularly to the high (and therefore dangerous) stress domain, compared with the medical foam. The Katzengold and Gefen 100 study concluded that, while the donut‐shaped gel head support design assumes dispersion of tissue loads away from the centre of the occiput, this concept fails to protect the scalp tissues. On the contrary, donut‐shaped head positioners allow the head weight forces to transfer through a relatively narrow ring of scalp tissues, thus increasing the risk of developing occipital PUs during supine surgery (Figure 4). 100 These donut‐shaped devices should therefore not be used for head positioning during surgery, as well as in other settings. 100

FIGURE 4.

The risk to occipital scalp tissue health when using a donut‐shaped gel (shown in the top frame) or foam head positioner, visualised by means of a three‐dimensional anatomically realistic computer model of the human head (graphics adopted from 100 ). The model incorporates the facial soft tissue structures, the scalp tissues, and the skull/cervical spine (A). High tissue distortion regions are coloured red. The donut‐shaped head positioner is found to allow the head weight forces to transfer through a relatively narrow ring of scalp tissues, thus increasing the risk of developing occipital pressure ulcers (conforming to the ring shape of the donut positioner) during supine surgery (B)

4.7. Contemporary technology‐based surgical positioners

An effective technology to alleviate stress concentrations and exposures in soft tissues is to use support surfaces that are designed to maximise immersion and envelopment. These features can be achieved, for example, through the use of a low‐pressure air chamber overlay positioning device that adapts to the body contours by air displacements. 101 Additional tissue protection can be provided to specific anatomical sites, for example, the occiput and heels in supine surgery or the breasts, knees, genitalia, and dorsal feet in prone surgery, by means of shape memory positioners, also known as fluidised positioners. 88 , 100 , 102 These are positioners made of viscoelastic composite materials that can be manually moulded into any shape—often the mirror shape of the body surfaces—and will maintain that shape, even under continuous bodyweight forces. 83 Furthermore, fluidised positioners relax rapidly under bodyweight forces, as opposed to the push back that is applied by foams on tissues because of the inherent elastic recoil behaviour of foams. 88 The OR nursing team shapes each fluidised positioner manually in preparation for surgery, moulding the positioners to conform to the body surfaces that are expected to be at high risk in the desired surgical position. By doing so, the team maximises the body envelopment at the at‐risk anatomical sites for the individual surgical patient, which is a fundamentally different approach than using standard foam or gel positioners that do not conform to the individual. For example, in supine surgery, a fluidised positioner placed under the head can be moulded to the exact (mirror) shape of the back of the head to redistribute the weight of the head onto the largest possible head‐positioner contact area. Such fluidised positioners can further be folded away from sensitive tissue sites or tubes, for example, the ears or the eyes and endotracheal tube, or be moulded away from an existing PU if needed. Using a combination of advanced positioning equipment should always be considered: (a) a low‐pressure air chamber overlay that provides whole‐body protection through immersion and envelopment, together with (b) fluidised positioners that increase the body envelopment locally and (c) prophylactic dressings that deliver targeted protection to specific at‐risk sites, especially from shearing of tissues. The aforementioned hybrid technological approach is considered by the authors to be the most effective for prevention of intraoperative PUs and neural tissue damage. 101 , 102

5. CHALLENGES IN POSITIONING PRONE SURGICAL PATIENTS

Prone surgical positioning used in posterior cranial and spinal procedures is associated with an especially high risk of PUs and neural damage and, potentially, catastrophic complications that may result in permanent disability. 33 Positioning the body in a prone posture for surgery applies localised forces to delicate organs and tissue structures, including the facial tissues, the breasts for females, the lower costal margins, the anterior iliac crests, the genitalia (particularly for males), the knees, the shins, and the dorsal feet (Figure 5A). Accordingly, intraoperative PUs are common in patients positioned prone. 33 Neural injuries have also been reported to occur in patients who are prone. Specifically, direct compression of the eye globes, which in turn causes decreased perfusion of the retina, is known to cause permanent visual loss (typically unilateral) in 0.02 to 0.2% of spinal surgeries. 103 Another, more common neural injury that is associated with prone positioning is brachial plexus damage. The brachial plexus innervates the musculature of the upper body and delivers sensation to the upper limbs. 104 It is fixed at the cervical vertebrae and the axillary fascia and passes near the clavicle, first rib, and humeral head, each of which may compress or stretch the delicate plexus tissues in the prone position, leading to plexus injuries at approximately 3% of the prone surgeries (the majority of cases are partially or fully reversible within weeks to months). 25 Likewise, ulnar nerve injuries or lateral femoral cutaneous nerve neuropathies can occur because of pressure and shear over the cubital tunnel at the elbows or the anterior superior iliac spine, respectively. There are specialty OTs for prone (spine) surgeries, which are commonly designed to reduce the intra‐abdominal pressure and the associated blood loss during prone surgery. These OTs leave the abdomen off‐loaded to reduce bleeding, which consequently shifts and concentrates additional bodyweight forces at the aforementioned supported areas. The available OTs for prone surgeries differ in their effect on the spinal alignment, location of the sites for primary transfer of bodyweight forces, and the haemodynamic performances in the prone position. The OTs used for spine corrections can be, for example, two V‐shaped supports, one under the upper thoracic cage and the other under the pelvis, or can comprise parallel, longitudinal curved pads that support both sides of the torso. In all configurations, however, the authors recommend to use an integrative protective suite of products, including an advanced overlay designed for the specific prone frame, fluidised positioners, and prophylactic dressings applied to the face, chest, iliac crests, and shins for maximising tissue protection. 105 Computer modelling work conducted in the research group of author AG (reviewed in 95 ) allows to test the biomechanical efficacy of interventions, for example, positioners and prophylactic dressings in protecting soft tissue structures in prone‐positioned patients (Figure 5B).

FIGURE 5.

Intraoperatively acquired forehead pressure ulcers: (A) The location and shape of the injury is typical in patients who were operated in a prone position. (B) Computer modelling of an adult head in a prone surgical position. The model, which incorporates soft facial tissues, as well as the skull and cervical spine structure, confirms that the forehead is susceptible to intraoperatively acquired pressure ulcers in a prone surgical position and allows us to assess the biomechanical efficacy of interventions, for example, the specific surgical pad mounted on the operation table and use of positioners and prophylactic dressings

Interestingly, the association between prone positioning and the high PU risk related to this position recently became a highly relevant topic as the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic broke out. There has been a worldwide and dramatic increase in the use of prone positioning in ICUs to treat acute respiratory distress syndrome in COVID‐19 patients. 94 While considering that COVID‐19 patients are inherently different from surgical patients, it is expected that the global clinical experience accumulated with regard to prevention of PUs among these ICU COVID‐19 patients can later be translated (with required adaptations) to the OR setting and practice.

6. CLINICAL HIGHLIGHTS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Predicting risk for perioperative‐acquired PUs remains elusive 107 , 109 , 111 . Risk assessments alone have little predictive power, and clinical judgement is therefore very important. Clearly, the length of the operation is the primary factor, as detailed in this paper, but the true length of any operation is only known after surgery is complete. Therefore, the nurses should examine the surgical schedule for predicted time for the operation. If the operation is listed to require over 2 to 3 hours (depending on the surgical position; prone positions typically involve greater risk), consider the patient to be at risk of PU development. The positions used for surgery create their own patterns of PU development, and preventive dressings or other padding should be applied to those body areas. If the patient's body shape or habitus has prominent bony areas, they should also be padded. Other risk factors include the relative degree of patient comorbid states, which is most efficiently obtained by the American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA) score (rather than trying to account for all other conditions).

The position of the body during the operation is seldom known by the preoperative staff because it does not appear on surgical case lists. Providing images of the most common surgical positions and their associated PU locations would be instructive and of high educational value to preoperative nurses. The 2019 International Guideline on Pressure Ulcer/Injury Prevention and Treatment (EPUAP/NPIAP/PPPIA Guideline)108 includes diagrams of the common surgical positions and associated PU locations. Prophylactic dressings for which there is published peer‐reviewed evidence for biomechanical efficacy 95 should be placed on the sacrum and buttocks during skin assessment, prior to surgery, while the patient is awake and can move to facilitate placement.

The perioperative nurses (ie, all nurses working in the operative area) are central to the safe and proper position of patients on the OT. Because turnover time is crucial to efficiency, the devices needed for PU prevention during surgery must either be in the pack of surgical supply or very close to the OR. When time is lost trying to find equipment, it will soon be omitted entirely. Prophylactic dressings are sterile and can be added to the sterile preparation areas. Such dressings should be placed on the body for prone cases after the patient is anaesthetised and prior to turning or placing on the operative frames. Positioners should be placed and moulded to the patient prior to draping. Anaesthesia personnel should place the head positioner. Caution should be used when the back table or instrument table (“Mayo stand”) is moved into position so that it rests on the patient, especially if the height of the OT is raised.

Devices used for positioning patients can show signs of wear and tear (the biomechanical consequences of which have been discussed here) and yet continue to be used. Nurses should be aware of aging devices, such as foams that do not regain their shape, gels that are flat in certain areas, and pillows that flatten out when bodyweight is applied. The OT pad, in particular, is frequently overlooked as a worn‐out device. Examine the OT pad and determine if it is at least 2 in. thick (as a minimum; the OT pad should desirably be thicker and up to 5 in.). Also examine policy for replacement of OT pads and positioners. This raises the important point of how valuable it is to have OR nursing representation on hospital committees responsible for purchasing or replacing products and equipment. Practicing evidence‐based nursing care in the prevention of OR‐related positioning injuries requires access to products proven to decrease PUs. As proper positioning in the OR is a primary task for OR staff nurses, it is incumbent upon them to be up‐to‐date and educated on various devices on the market. Advocating for the purchase of products with valid, non‐biased, evidence‐based, scientific, clinical, and financial outcomes is crucial to the organisational success of reducing OR‐associated hospital‐acquired PUs.

Following surgery, the handoff to recovery nurses and floor nurses should include the duration of surgery, blood loss or prolonged hypotension, the position the patient was in for the operation, and any equipment that could have caused tissue damage (such as the peroneal post). 112 The EPUAP/NPIAP/PPPIA Guideline instructs nurses to position the patient in another position than that used for the surgery, both pre‐ and postoperatively, in order to off‐load bodyweight forces from tissues. For example, if a patient was supine for surgery, they should be turned on to the side. This position change should occur as soon as possible after surgery and in the pre‐op holding area if feasible. Educating the patient will be helpful; even a statement such as “you have been on your back all day, let's get you turned onto your side to give your back a rest” can be encouraging. Early ambulation is an excellent method to getting patients into a position that will allow alleviation of the sustained tissue deformations and perfusion of the tissue regions subjected to continuous distortions during surgery. Use caution, however, that the patient is not simply put into the same position on another device, for example, moving the patient to a cardiac or geri‐chair often does little to reduce loading on their sacrum. Likewise, if the patient is placed in a bedside chair, be certain the chair is well‐padded, and the patient changes position in their chair at least every hour, and more frequently if possible.

Root cause analysis as part of a quality improvement programme is imperative to reducing hospital‐acquired PU rates. 113 For example, a patient who was positioned in high Fowler's for surgery 48 hours ago with sacral DTI discovered today likely developed them during surgery. In contrast, a patient who was ill at home with respiratory distress and had surgery to drain an empyema who presents with DTI on the sacrum likely did not develop that wound in the OR because he was likely planed or positioned on the side for surgery. Including the OR nursing staff in investigations of possible causes of PUs that may have been initiated during surgery (and doing so early after the PU has been discovered) is imperative to any successful quality improvement programme.

7. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

This scoping review analysed the existing, contemporary evidence regarding surgical positioning‐related tissue damage risks, from both biomechanical and clinical perspectives, focusing on the challenges in preventing tissue damage in the constraining OR environment, which does not allow repositioning and limits the use of dynamic or thick and soft support surfaces. Deep and multidisciplinary aetiological understanding is required for effective prevention of intraoperatively acquired tissue damage, and as in the above example of the donut‐shaped head positioner, lack of such understanding typically leads to misconceptions and increased risk to patients. This article therefore provided a comprehensive aetiological description concerning the types of potential tissue damage, vulnerable anatomical locations, the risk factors specific to the OR setting (eg, the effects of anaesthetics and instruments), the complex interactions between the tissue damage risk and the pathophysiology of the surgery itself (eg, the inflammatory response to the surgical incisions), risk assessments for surgical patients and their limitations, and available (including emerging) technologies for positioning. The present multidisciplinary and integrated approach, which holistically joins the bioengineering and clinical perspectives, is unique to this work and has not been taken before. Close collaboration between bioengineers and clinicians is required to revisit the design of OTs, OR support surfaces, surgical instruments for patient stabilisation, and surgical access so that each type of equipment and their combined use will become safer with regard to the two major OR threats to tissue health: PUs and neural damage.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Ms. Lea Peko of the research group of Prof. Amit Gefen is thanked for her work on the computer simulation of the prone head. The study was supported by an unrestricted educational grant from Mölnlycke Health Care (Gothenburg, Sweden).

Gefen A, Creehan S, Black J. Critical biomechanical and clinical insights concerning tissue protection when positioning patients in the operating room: A scoping review. Int Wound J. 2020;17:1405–1423. 10.1111/iwj.13408

Funding information Mölnlycke Health Care (Gothenburg, Sweden), Grant/Award Number: N/A

REFERENCES

- 1. Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5:69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sucharew H, Macaluso M. Methods for research evidence synthesis: the scoping review approach. J Hosp Med. 2019;7:416‐418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Servant C, Purkiss S, Hughes J. Positioning Patients for Surgery. 2nd ed. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kneedler JA, Dodge GH. Positioning the patient. In: Perioperative Patient Care: the Nursing Perspective. 3rd ed. Sudbury MA, USA: Jones and Bartlett Publishers; 1994:319‐332. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lustig M, Wiggermann N, Gefen A. How patient migration in bed affects the sacral soft tissue loading and thereby the risk for a hospital‐acquired pressure injury. Int Wound J. 2020;17(3):631‐640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gefen A, Brienza D, Edsberg L, et al. The etiology of pressure injuries. In: Prevention and Treatment of Pressure Ulcers/Injuries: Clinical Practice Guideline European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (EPUAP), National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel (NPIAP) and the Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance (PPPIA). 3rd ed. Westford, MA, USA: EPUAP‐NPIAP‐PPPIA; 2019a. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Alderden J, Whitney JD, Taylor SM, Zaratkiewicz S. Risk profile characteristics associated with outcomes of hospital‐acquired pressure ulcers: a retrospective review. Crit Care Nurse. 2011;31(4):30‐43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kimsey DB. A change in focus: shifting from treatment to prevention of perioperative pressure injuries. AORN J. 2019;110(4):379‐393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Aronovitch SA. Intraoperatively acquired pressure ulcers: are there common risk factors? Ostomy Wound Manage. 2007;53(2):57‐69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fawcett D, Black J, Scott S. Ten top tips: preventing pressure ulcers in the surgical patient. Wounds Int. 2014;5(4):14‐18. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Karadag M, Gümüskaya N. The incidence of pressure ulcers in surgical patients: a sample hospital in Turkey. J Clin Nurs. 2006;15(4):413‐421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Papantonio CT, Wallop JM, Kolodner KB. Sacral ulcers following cardiac surgery: incidence and risks. Adv Wound Care. 1994;7(2):24‐36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Primiano M, Friend M, McClure C, et al. Pressure ulcer prevalence and risk factors during prolonged surgical procedures. AORN J. 2011;94(6):555‐566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Engels D, Austin M, McNichol L, Fencl J, Gupta S, Kazi H. Pressure ulcers: factors contributing to their development in the OR. AORN J. 2016;103(3):271‐281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pokorny M, Koldjeski D, Swanson M. Skin care intervention for patients having cardiac surgery. Am J Crit Care. 2003;12:535‐544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sanada H, Nagakawa T, Yamamoto M, Higashidani K, Tsuru H, Sugama J. The role of skin blood flow in pressure ulcer development during surgery. Adv Wound Care. 1997;10(6):29‐34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Galivanche AR, Kebaish KJ, Adrados M, et al. Postoperative pressure ulcers after geriatric hip fracture surgery are predicted by defined preoperative comorbidities and postoperative complications. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2020;28(8):342–351. 10.5435/JAAOS-D-19-00104 in press, available online. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chen HL, Jiang AG, Zhu B, Cai JY, Song YP. The risk factors of postoperative pressure ulcer after liver resection with long surgical duration: a retrospective study. Wounds. 2019;31(9):242‐245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yoshimura M, Nakagami G, Iizaka S, et al. Microclimate is an independent risk factor for the development of intraoperatively acquired pressure ulcers in the park‐bench position: a prospective observational study. Wound Repair Regen. 2015;23(6):939‐947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yoshimura M, Iizaka S, Kohno M, et al. Risk factors associated with intraoperatively acquired pressure ulcers in the park‐bench position: a retrospective study. Int Wound J. 2016;13(6):1206‐1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. De Backer D, Foulon P. Minimizing catecholamines and optimizing perfusion. Crit Care. 2019;23(suppl 1):149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fred C, Ford S, Wagner D, Vanbrackle L. Intraoperatively acquired pressure ulcers and perioperative normothermia: a look at relationships. AORN J. 2012;96(3):251‐260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hayes RM, Spear ME, Lee SI, et al. Relationship between time in the operating room and incident pressure ulcers: a matched case‐control study. Am J Med Qual. 2015;30(6):591‐597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Grap MJ, Schubert CM, Munro CL, et al. OR time and sacral pressure injuries in critically ill surgical patients. AORN J. 2019;109(2):229‐239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Uribe JS, Kolla J, Omar H, et al. Brachial plexus injury following spinal surgery. J Neurosurg Spine. 2010;13(4):552‐558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Goettler CE, Pryor JP, Reilly PM. Brachial plexopathy after prone positioning. Crit Care. 2002;6(6):540‐542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cho KT, Lee HJ. Prone position‐related meralgia paresthetica after lumbar spinal surgery: a case report and review of the literature. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2008;44(6):392‐395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lalkhen AG, Bhatia K. Perioperative peripheral nerve injuries. Cont Edu Anaesth Crit Care Pain. 2012;12(1):38‐42. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chui J, Murkin JM, Posner KL, Domino KB. Perioperative peripheral nerve injury after general anesthesia: a qualitative systematic review. Anesth Analg. 2018;127(1):134‐143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Moore AE, Zhang J, Stringer MD. Iatrogenic nerve injury in a national no‐fault compensation scheme: an observational cohort study. Int J Clin Pract. 2012;66:409‐416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ben‐David B, Stahl S. Prognosis of intraoperative brachial plexus injury: a review of 22 cases. Br J Anaesth. 1997;79(4):440‐445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schonauer C, Bocchetti A, Barbagallo G, Albanese V, Moraci A. Positioning on surgical table. Eur Spine J. 2004;13(suppl 1):S50‐S55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. DePasse JM, Palumbo MA, Haque M, Eberson CP, Daniels AH. Complications associated with prone positioning in elective spinal surgery. World J Orthop. 2015;6(3):351‐359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Takai S, Dohno H, Watanabe Y, Yoshino N, Ogura T, Hirasawa Y. In situ strain and stress of nerve conduction blocking in the brachial plexus. J Orthop Res. 2002;20(6):1311‐1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kwan MK, Wall EJ, Massie J, Garfin SR. Strain, stress and stretch of peripheral nerve. Rabbit experiments in vitro and in vivo. Acta Orthop Scand. 1992;63(3):267‐272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wong SF, Chung F. Succinylcholine‐associated postoperative myalgia. Anesthesia. 2000;55(2):144‐152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kim KN, Kim KS, Choi HI, Jeong JS, Lee HJ. Optimal precurarizing dose of rocuronium to decrease fasciculation and myalgia following succinylcholine administration. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2014;66(6):451‐456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Shafy S, Hakim M, Krishna S, Tobias J. Succinylcholine‐induced postoperative myalgia: etiology and prevention. J Med Cases. 2018;9:264‐266. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Poon PW, Lui PW, Chow LH, Lam FK, Chan FH, Lin YM. EMG spike trains of succinylcholine‐induced fasciculations in myalgic patients. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1996;101(3):206‐210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pinho‐Ribeiro FA, Verri WA Jr, Chiu IM. Nociceptor sensory neuron‐immune interactions in pain and inflammation. Trends Immunol. 2017;38(1):5‐19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dubin AE, Patapoutian A. Nociceptors: the sensors of the pain pathway. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(11):3760‐3772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mense S. Functional anatomy of muscle: muscle, nociceptors and afferent fibers. In: Mense S, Gerwin R, eds. Muscle Pain: Understanding the Mechanisms. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Power H. Patient positioning outcomes for women undergoing gynaecological surgeries. Can Oper Room Nurs J. 2002;20(3):7‐10. 27‐30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Aronovitch SA. Intraoperatively acquired pressure ulcer prevalence: a national study. Adv Wound Care. 1998;11(suppl 3):8‐9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Price MC, Whitney JD, King CA, Doughty D. Development of a risk assessment tool for intraoperative pressure ulcers. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2005;32(1):19‐30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Scott EM, Leaper DJ, Clark M, Kelly PJ. Effects of warming therapy on pressure ulcers ‐ a randomized trial. AORN J. 2001;73(5):921‐927. 929–33, 936–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Schoonhoven L, Defloor T, van der Tweel I, Buskens E, Grypdonck MH. Risk indicators for pressure ulcers during surgery. Appl Nurs Res. 2002;15(3):163‐173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Fife CE, Gkotsoulias E. On the origin of intraoperative pressure injury: an Angiosomal theory of pressure injury formation. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2019;8(11):580‐584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wicker P, Nightingale A. Patient care during surgery. In: Wicker P, O'Neill J, eds. Caring for the Perioperative Patient. 2nd ed. Chichester, West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Toussaint RJ, Abousayed MM, Kwon JY. Preventing falls in the operating room: a technique tip for safely tilting the operating table. Foot Ankle Spec. 2013;6(5):372‐375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Scott SM. Perioperative pressure injuries: protocols and evidence‐based programs for reducing risk. Patient Saf Qual Healthcare. 2016;13(4):21‐28. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kumagai A, Ohno N, Miyati T, et al. Investigation of effects of urethane foam mattress hardness on skin and soft tissue deformation in the prone position using magnetic resonance imaging. J Tissue Viability. 2019;28(1):14‐20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]