Abstract

Laser Doppler velocimetry estimates tissue perfusion providing a record of microvascular blood flow. Patients with heart disease or diabetes mellitus have impaired microvascular perfusion leading to impaired wound healing. Aged garlic extract (AGE) has a positive effect on vascular elasticity. This study aimed to assess the effect of long‐term treatment with AGE on cutaneous tissue perfusion. A total of 122 patients with Framingham Risk Score ≥ 10 were randomised in a double‐blinded manner to placebo or 2400 mg AGE daily for 1 year and monitored. Cutaneous microcirculation was measured at 0 and 12 months using laser Doppler velocimetry. A repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a Greenhouse–Geisser correction determined that mean post‐occlusive reactive hyperaemia differed significantly between time points. The mean percent change between the two time points 0 and 12 months was 102, 64 (174, 15)% change for AGE and 78, 62 (107, 92)% change for the placebo group (F[1, 120] = 5. 95, P < 0.016), 12 months of AGE increases the microcirculation in patients with an increased risk for cardiovascular events estimated using the Framingham risk score. Increased microcirculation could hypothetically facilitate wound healing.

Keywords: aged garlic extract, atherosclerosis, cutaneous microcirculation, double blinded, laser Doppler velocimetry

1. INTRODUCTION

Arteriosclerosis complications are the most common cause of death in the Western world.1, 2 Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a complication secondary to arteriolosclerosis. Arterial inflammation and endothelial dysfunction play central roles in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis and adverse cardiovascular events.3 The major risk factors for CVD are hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, diabetes, and obesity. Framingham risk score is a risk‐stratifying score system for estimating the risk of developing CVD. CVD risk factors are well known to enhance the development of atherosclerotic lesions in arteries, but have also been suggested to impair the microvascular circulation and tissue perfusion. Reduced microcirculation has even been suggested to be an early marker for CVDs4, 5, 6 and is also involved in impaired wound healing, especially in persons with diabetes mellitus.

The microcirculation commonly includes the smallest arteries, the arterioles, capillaries, and venules. Exchange of gases, nutrients, and metabolites between the blood and tissues occurs almost solely in the microcirculation, and sufficient perfusion via the microcirculatory system is crucial for organ function, and the integrity of tissue and wound healing. Alterations in microcirculation are correlated with oxidative stress, enhanced platelet‐endothelial cell adhesion, endothelial dysfunction, altered capillary proliferation, and vasomotor dysfunction resulting in arterial stiffness and vessel narrowing.7 The alterations might, in turn, be a response of a low‐grade systemic inflammatory response.8, 9 The association between impaired endothelial function and cardiovascular risk in asymptomatic patients has been poorly explored.

Aged garlic extract (AGE) has been suggested to have a positive effect on vascular elasticity and endothelial function.10, 11, 12 Non‐invasive laser Doppler velocimetry (LDV) is a well‐known technology for functional testing of endothelium‐dependent microvascular reactivity. LDV provides a continuous record of the microvascular blood flow, and is, therefore, an excellent method to measure microvascular blood flow changes and microvascular perfusion.13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21

This study aimed to assess alterations in cutaneous microvascular perfusion over a period of 12 months. Measurements were made at 0 and after 12 months of treatment of either placebo or 2400 mg AGE daily in 122 patients with Framingham Risk Score ≥ 10. The aim of this study was also to assess the effectiveness of AGE on cutaneous microvascular perfusion in patients with increased risk for cardiovascular events, using a double‐blinded placebo‐controlled randomised trial design. The primary outcome of this study was to examine if 12 months of AGE treatment could improve the cutaneous microvascular perfusion measured with LDV on patients with an increased risk for cardiovascular events. To our knowledge, no such study has been performed previously.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was designed as a double‐blinded placebo‐controlled randomised study to determine whether AGE can improve microvascular circulation. The study was approved by the local ethical committee Dnr 2016/745. The study protocol was registered at (https://register.clinicaltrials.gov) with ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03860350. The study was monitored externally by Preventia AB, Sweden https://www.preventia.se/en/startsida/.

For inclusion and exclusion criteria please see Table 1.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for patients in the study

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Age 40 to 75 | Myocardial infarction |

| Framingham risk score > 10 | Ischaemic heart disease |

| Stable medications for 4 mo prior to randomisation | History of malignancy within the last 5 y or evidence of active cancer |

| Subjects with diabetes had to have a glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) < 8.0 and stable HbA1c level (variation range within 0.5%) for 6 mo | Resting hypotension (systolic <90 mm Hg) or hypertension (resting blood pressure > 170/110) |

| Serum creatinine >140 μmol/L | |

| Prior life‐threatening arrhythmia | |

| Unstable medical disorder | |

| Heart failure NYHA class III or IV | |

| Hypersensitivity to AGE | |

| Diabetic subjects with HbA1c > 8.0 | |

| Triglycerides >4.0 mmol/L baseline visit | |

| Bleeding disorder or stroke or drug abuse |

2.1. Randomisation

A total of 134 patients met the inclusion criteria and were randomised in a double‐blinded manner, using numbered containers assigned to a computer‐generated randomisation chart. The patients were randomised to an intake of capsules with 2400 mg AGE daily daily (two capsules of 600 mg twice daily, Kyolic Reserve formula; Wakunaga of America Co Ltd, Mission Viejo, CA) or two placebo capsules twice daily.

2.2. Clinical evaluation

Medical evaluation including medical history, cardiovascular risk factors, prescribed medications, smoking, and alcohol intake was performed at 0, 4, 8, and 12 months. In addition to blood pressure measurement, body mass index measurement, electrocardiogram measurements, and assessment of patients' compliance with medication were carried out. Blood pressure was measured after 10 minutes' rest in a comfortable supine position by an automatic blood pressure monitor (OMRON Automatic Blood Pressure Monitor Model M6 Comfort IT, Spånga, Sweden).

2.3. Microvascular blood flow measured using LDV

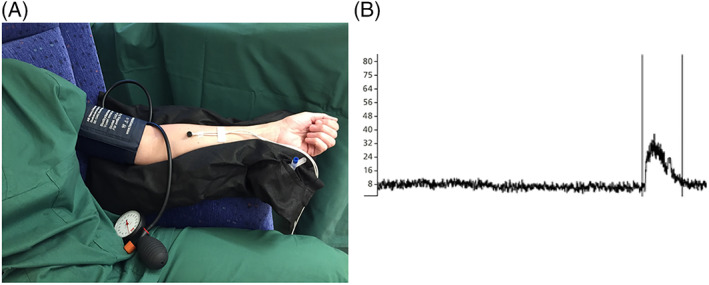

Microvascular blood flow was measured using LDV (Transonic Laser Doppler Monitor, BLF21, Maastricht, the Netherlands, and Peri Flux System 5000, Perimed, Stockholm, Sweden), using a technique that quantifies the sum of the motion of the red blood cells in a specific volume. This method is applied extensively in plastic surgery procedures and uses a fibre optic probe carrying a beam of light. Light impinging on cells in motion undergoes a change in wavelength (Doppler shift) whilst light impinging on static objects remains unchanged. The magnitude and frequency distributions of the changes are related directly to the number and velocity of red blood cells. The information is collected by a returning optic fibre, converted into an electronic signal, and analysed. Measurements are expressed as perfusion units (PU), which are arbitrary.13 All measurements were performed in a quiet and temperature‐controlled room. The study was conducted with ≥10 hours of abstinence from tobacco, alcohol, caffeine, or exercise. The patients had 30 minutes of acclimatisation time in a temperature‐controlled study room before the measurements were made. The measurements were made on the forearm before partial occlusion, during partial occlusion and during post‐occlusive reactive hyperaemia (PORH) using a manual blood pressure cuff (Boso Varius, AB Henry Eriksson, Bandhagen, Sweden) inflated at 250 mm Hg for 3 minutes. The position of the probe was exactly 10 cm below the elbow joint on the ventral side of the forearm exactly in the middle and chosen so hair, freckles, and broken skin were avoided. The study setup is shown in Figure 1A.

Figure 1.

(A) A clinical setup with laser Doppler velocimetry (LDV). The measurements were made on the forearm before and during post occlusive reactive hyperaemia (PORH). (B) An example of an output data file from the LDV. The difference in LDV perfusion units between measurements was considered a proxy of microcirculation

2.4. Ethical considerations

This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving human patients were approved by the local ethical committee DNR 2016/745. All participants signed a written consent form before entering the study. The study protocol was registered at (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03860350?term=NCT03860350&rank=1) with ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03860350. The study was monitored externally by Preventia AB, Sweden, https://www.preventia.se/en/startsida/.

2.5. Statistics

A power analysis was based on the previously published studies evaluating the effect of garlic and supplements on coronary atherosclerosis, blood pressure, cholesterol, and inflammatory biomarkers.22, 23 All continuous data are presented as a mean value ± SD. A repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a Greenhouse–Geisser correction was performed to test for differences between groups between time points 0 and 12 months. Post hoc tests using the Bonferroni correction were used to make comparisons between time points within treatment groups, AGE supplement, and Placebo. The biological zero in LDV measurements was taken into consideration.24 All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS V 19.0 (SPSS Institute, Chicago, Illinois). The level of significance was set to P < 0.05. The statistics were calculated by Andreas Timglas, at Fanwl Consulting AB.

3. RESULTS

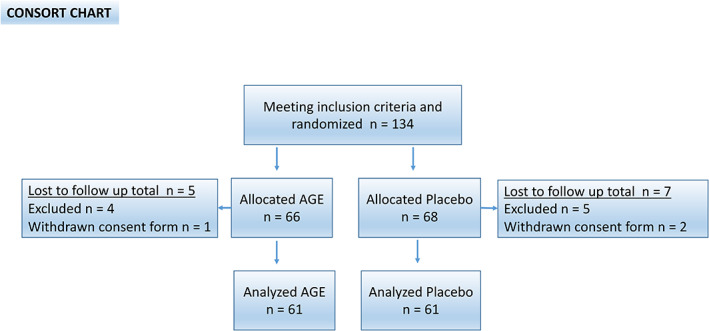

In total, 134 patients were enrolled and randomised in the study, 12 participants were excluded during the study and consequently 122 patients, 60 in the AGE group and 62 in the placebo group, were analysed, see CONSORT (Consolidate Standards of Reporting Trials) outlined in Figure 2. No patient in the study had any adverse reaction of the active therapy that indicated removal from the study. At baseline, there were no significant differences in cardiovascular risk factors calculated using the Framingham risk score. Patient demographics are shown in Table 2.

Figure 2.

CONSORT statement (consolidated standards of reporting trials) flow chart. Showing demographics and baseline clinical information of the study cohort

Table 2.

Patient demographics at baseline

| Variable | Age | Placebo | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 60 | % | n = 62 | % | ||

| Age (y) (SD) | 64 | (SD 6) | 64 | (SD 6) | 0.93 |

| Gender (male) | 30 | 50 | 31 | 50 | 1.0 |

| Hypertension | 48 | 80 | 51 | 82 | 0.75 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 41 | 66 | 27 | 45 | 0.02 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 8 | 13 | 15 | 24 | 0.13 |

| Current smoker | 5 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 0.60 |

| Family history of CVD | 45 | 75 | 40 | 65 | 0.30 |

| Framingham risk score | 20 | (SD 8) | 20 | (SD 7) | 0.86 |

CVD, cardiovascular disease; SD, standard deviation.

3.1. Microvascular measurements at 0 and 12 months measured before, during, and after partial occlusion creating a PORH response

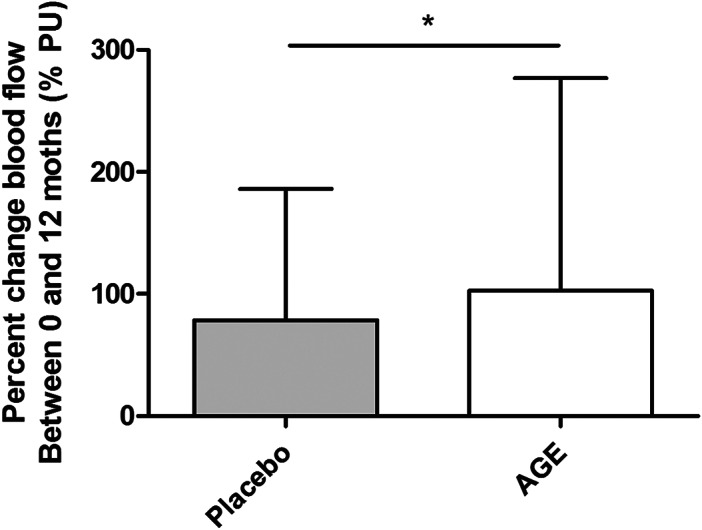

Microcirculation was measured using LDV at 0 and 12 months. The measurements were made on the forearm before, during partial occlusion, and during reperfusion after a partially induced ischaemia, PORH, by compression using a manual blood pressure cuff inflated with 250 mm Hg for 3 minutes. The microvascular blood flow was 9. 7 ± (4.9) PU in the AGE group and 9.3 ± (5.0) PU in the placebo group at 0 months before partial occlusion. The microvascular blood flow was 3.5 ± (0.89) PU in the AGE group and 3.8 ± (3.5) PU in the placebo group during the partial occlusion. The microvascular blood flow was 49.9 ± (29.9) PU in the AGE group and 43. 9 ± (22.0) PU in the placebo group at 0 months during PORH. The same measurements were made after 12 months of either placebo or AGE treatment. The microvascular blood flow was 16.0 ± (7.4) PU in the AGE group and 13.9 ± (5.8) PU in the placebo group before partial occlusion. The microvascular blood flow was 7.9 ± (3.6) PU in the AGE group and 6.5 ± (3.3) PU in the placebo group during the partial occlusion. The microvascular blood flow was 47.3 ± (22.7) PU in the AGE group and 46.6 ± (23.7) PU in the placebo group at 12 months during PORH. See Figure 1B for an example of an output data file from the LDV. The mean percent changes between the two time points 0 and 12 months were 102, 64 (174, 15) % change for AGE and 78, 62 (107, 92) % change for the placebo group (F[1, 120] = 5. 95, P < 0.016) shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The mean percent change in blood flow measured using laser Doppler velocimetry (LDV). Measurements are carried out between 0 and 12 months between the different groups; AGE and placebo

4. DISCUSSION

The present study demonstrates that 12 months of AGE supplement preserves and even improves cutaneous microcirculation measured by LDV compared with the placebo group. LDV is a well‐known technology that can measure the velocimetry on blood cells and is therefore an excellent method to measure microvascular blood circulation and tissue perfusion.13, 16, 20, 21 Alterations in microcirculation are correlated with impaired endothelial function and a low‐grade inflammatory response.7, 8, 9 Impaired vascular endothelial function and impaired cutaneous tissue perfusion on the other hand have attracted attention as prognostic indicators of cardiovascular prevention and are involved in impaired wound healing, especially in persons with diabetes mellitus.

The endothelium covers the interior wall of the vessels and has a major impact on blood pressure regulation, microvascular blood flow, and tissue perfusion. Nitric oxide (NO) is synthesised from the amino acid L‐arginine in endothelial cells by the constitutive calcium‐calmodulin‐dependent enzyme nitric oxide synthase (NOS) and causes vasodilation by relaxation of the smooth muscle cells of the vascular walls. NO has wide‐ranging biological properties and plays a crucial role in the normal endothelial function. Several conditions, including those commonly associated as risk factors for atherosclerosis such as hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, and diabetes mellitus are associated with reduced release of NO. Therefore, endothelial dysfunction has been associated as an early sign of CVD.

Tests that cause endothelium‐dependent and/or independent vasodilation such as PORH are used to study the endothelial function and tissue perfusion. Reactive hyperaemia is an increase in blood flow as a result of a temporary occlusion of an arterial blood supply leading to an oxygen deficit. Patients with impaired endothelial function show a different response than healthy controls. In PORH, a partial arterial occlusion is performed, as in the present study by using a blood pressure cuff inflated to 250 mm Hg for 3 minutes. After the partial occlusion, the pressure is released, resulting in a large inflow of blood into the previously occluded tissue. The perfusion is measured before the occlusion, during the occlusion and after the occlusion. Parameters related to both magnitude, occlusion and baseline measurements before occlusion give information about the vascular health of the patient.

The present study included a total of 134 patients, and 122 patients were analysed after 12 months. Twelve patients were either excluded because of changes in medication during the study or they withdrew their informed consent. This is the largest study ever performed evaluating AGE effects on microvascular blood flow and cutaneous tissue perfusion. There are a few other studies describing the AGE effect on microvascular blood flow. Ahmadi et al. showed increased microvascular blood flow in a randomised trial on 60 patients with AGE supplement and placebo using digital thermal monitoring measurements of the fingertips before, during and after PORH.10 Weiss et al. showed in a 6‐week trial on 11 healthy subjects increased microvascular blood flow using acetylcholine‐induced vasodilation on the forearm.12 Another randomised AGE placebo‐controlled study evaluated arterial stiffness by measuring the pulse wave velocity also showed increased vascular elasticity.25

Atherosclerosis is a progressive disease leading to decreased microvascular blood flow and impaired cutaneous tissue perfusion over time. Previous studies have suggested that AGE improves endothelial function by anti‐oxidative effects.26, 27 Other studies have implicated that AGE increases the production of NO in endothelial cells suggesting an effect on the vascular tone and anti‐inflammation.28 Many studies have shown that NO production in the endothelium interferes with crucial mechanisms in the atherosclerotic process and inflammation.29 Preserving or even increasing the microvascular blood flow might be because of an inhibition of the atherosclerosis process by restoring natural compliance of vessels. However, it might also be because of increased angiogenesis, vascular neovascularisation, and by potentially affecting vascular tone and endothelial function, meaning restored vascular health and thereby improving wound healing.

The present study has both strengths and limitations. LDV is easily implemented, yet interpretation of the results needs to be made with some limitations in mind. LDV is sensitive to movement artefacts and to external factors such as changes in room temperature, stress, caffeine intake, nicotine intake, and exercise. There is limited knowledge of how differences in skin pigmentation, skin thickness, and proximity to larger vessel and capillary density affect the size of the LDV output. However, this was compensated for to some extent by using standardised measuring techniques according to the study protocol, controlled environment, and meticulous application of the measuring probe, and repeated measures on patients. All data from the laser Doppler files were extracted twice by two different researchers and the median values of those values were used for calculation. The study was monitored externally by a study monitor during the whole study period, who carefully secured that all values were correct and were adequate.

The present study demonstrates that 12 months of AGE supplement may preserve and even improve the microcirculation measured by LDV as seen in Figure 3. The effect might be because of an inhibition of the atherosclerosis process, but also by potentially affecting vascular tone and endothelial function. Preserving or even increasing the microvascular blood flow and cutaneous tissue perfusion may hypothetically facilitate wound healing.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

S.L. has received a research grant to support this research from Wakunaga of America Ltd. None of the other authors has conflicts of interest to disclose.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.W., J.H., and S.L. participated in the design of the study. S.L. wrote the application for the ethical approval. M.W., A.‐C.N., M.F., and S.L. carried out all clinical appointments. A.‐C.N. carried out all blood tests. A.‐C.N. and M.W. carried out the monitoring of the study together with Preventia AB. M.W., M.F., J.H., and S.L. analysed the study results. M.W. and S.L. drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Vera Celander for the help with advertising and recruitment of study patients. The study was funded by ALF foundation and SUS foundation. The study was also funded by a research grant to S.L. from Wakunaga of America Ltd. Wakunaga of America Ltd also provided the placebo and the AGE capsules used in this study free of charge. Wakunaga of America Ltd had no role in the design, analysis, or writing of this article.

Wlosinska M, Nilsson A‐C, Hlebowicz J, Malmsjö M, Fakhro M, Lindstedt S. Aged garlic extract preserves cutaneous microcirculation in patients with increased risk for cardiovascular diseases: A double‐blinded placebo‐controlled study. Int Wound J. 2019;16:1487–1493. 10.1111/iwj.13220

Funding information ALF Foundation, Grant/Award Number: N/A; SUS foundation; Wakunaga of America LTD

REFERENCES

- 1. Leys D. Atherothrombosis: a major health burden. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2001;11(suppl 2):1‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Singh RB, Mengi SA, Xu YJ, Arneja AS, Dhalla NS. Pathogenesis of atherosclerosis: a multifactorial process. Exp Clin Cardiol. 2002;7(1):40‐53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Glass CK, Witztum JL. Atherosclerosis. The road ahead. Cell. 2001;104(4):503‐516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Strain WD, Paldanius PM. Diabetes, cardiovascular disease and the microcirculation. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2018;17(1):57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lauten A, Ferrari M, Goebel B, et al. Microvascular tissue perfusion is impaired in acutely decompensated heart failure and improves following standard treatment. Eur J Heart Fail. 2011;13(7):711‐717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Levy BI, Schiffrin EL, Mourad JJ, et al. Impaired tissue perfusion: a pathology common to hypertension, obesity, and diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 2008;118(9):968‐976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bottino DA, Lopes FG, de Oliveira FJ, Mecenas Ade S, Clapauch R, Bouskela E. Relationship between biomarkers of inflammation, oxidative stress and endothelial/microcirculatory function in successful aging versus healthy youth: a transversal study. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15:41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hartman J, Frishman WH. Inflammation and atherosclerosis: a review of the role of interleukin‐6 in the development of atherosclerosis and the potential for targeted drug therapy. Cardiol Rev. 2014;22(3):147‐151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Machin DR, Phuong TT, Donato AJ. The role of the endothelial glycocalyx in advanced age and cardiovascular disease. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2019;45:66‐71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ahmadi N, Tsimikas S, Hajsadeghi F, et al. Relation of oxidative biomarkers, vascular dysfunction, and progression of coronary artery calcium. Am J Cardiol. 2010;105(4):459‐466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zeb I, Ahmadi N, Nasir K, et al. Aged garlic extract and coenzyme Q10 have favorable effect on inflammatory markers and coronary atherosclerosis progression: a randomized clinical trial. J Cardiovasc Dis Res. 2012;3(3):185‐190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Weiss N, Ide N, Abahji T, Nill L, Keller C, Hoffmann U. Aged garlic extract improves homocysteine‐induced endothelial dysfunction in macro‐ and microcirculation. J Nutr. 2006;136(3 Suppl):750S‐754S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zografos GC, Martis K, Morris DL. Laser Doppler flowmetry in evaluation of cutaneous wound blood flow using various suturing techniques. Ann Surg. 1992;215(3):266‐268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schabauer AM, Rooke TW. Cutaneous laser Doppler flowmetry: applications and findings. Mayo Clin Proc. 1994;69(6):564‐574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Anesater E, Borgquist O, Torbrand C, et al. The use of a rigid disc to protect exposed structures in wounds treated with negative pressure wound therapy: effects on wound bed pressure and microvascular blood flow. Wound Repair Regen. 2012;20(4):611‐616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lindstedt S, Malmsjo M, Hansson J, Hlebowicz J, Ingemansson R. Microvascular blood flow changes in the small intestinal wall during conventional negative pressure wound therapy and negative pressure wound therapy using a protective disc over the intestines in laparostomy. Ann Surg. 2012;255(1):171‐175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sheikh R, Memarzadeh K, Torbrand C, Blohme J, Lindstedt S, Malmsjo M. Blood perfusion in a full‐thickness eyelid flap, investigated by laser Doppler velocimetry, laser speckle contrast imaging, and thermography. Eplasty. 2018;18:e9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lindstedt S, Hansson J, Hlebowicz J. Comparative study of the microvascular blood flow in the intestinal wall during conventional negative pressure wound therapy and negative pressure wound therapy using paraffin gauze over the intestines in laparostomy. Int Wound J. 2012;9(2):150‐155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lindstedt S, Hlebowicz J. Blood flow response in small intestinal loops at different depths during negative pressure wound therapy of the open abdomen. Int Wound J. 2013;10(4):411‐417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lindstedt S, Malmsjo M, Hlebowicz J, Ingemansson R. Comparative study of the microvascular blood flow in the intestinal wall, wound contraction and fluid evacuation during negative pressure wound therapy in laparostomy using the V.a.C. abdominal dressing and the ABThera open abdomen negative pressure therapy system. Int Wound J. 2015;12(1):83‐88. 10.1111/iwj.12056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Malmsjo M, Ingemansson R, Lindstedt S, Gustafsson L. Comparison of bacteria and fungus‐binding mesh, foam and gauze as fillers in negative pressure wound therapy–pressure transduction, wound edge contraction, microvascular blood flow and fluid retention. Int Wound J. 2013;10(5):597‐605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Budoff MJ, Ahmadi N, Gul KM, et al. Aged garlic extract supplemented with B vitamins, folic acid and L‐arginine retards the progression of subclinical atherosclerosis: a randomized clinical trial. Prev Med. 2009;49(2–3):101‐107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Budoff MJ, Takasu J, Flores FR, et al. Inhibiting progression of coronary calcification using aged garlic extract in patients receiving statin therapy: a preliminary study. Prev Med. 2004;39(5):985‐991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhong J, Seifalian AM, Salerud GE, Nilsson GE. A mathematical analysis on the biological zero problem in laser Doppler flowmetry. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 1998;45(3):354‐364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ried K, Frank OR, Stocks NP, Fakler P, Sullivan T. Effect of garlic on blood pressure: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2008;8:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ide N, Lau BH. Garlic compounds minimize intracellular oxidative stress and inhibit nuclear factor‐kappa b activation. J Nutr. 2001;131(3s):1020S‐1026S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Imai J, Ide N, Nagae S, Moriguchi T, Matsuura H, Itakura Y. Antioxidant and radical scavenging effects of aged garlic extract and its constituents. Planta Med. 1994;60(5):417‐420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kim KM, Chun SB, Koo MS, et al. Differential regulation of NO availability from macrophages and endothelial cells by the garlic component S‐allyl cysteine. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;30(7):747‐756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bult H. Nitric oxide and atherosclerosis: possible implications for therapy. Mol Med Today. 1996;2(12):510‐518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.