Abstract

This study aims to test which factors influence and aid the psychosocial adjustment of patients with an ostomy and to provide data for the development of programmes for the self‐management of and psychosocial adjustment to intestinal stomas. A total of 150 ostomy patients were recruited between December 1, 2017 and March 26, 2018 in Korea and completed self‐report questionnaires. Data of 25 participants were excluded, resulting in a sample size of 125 participants. Factors, including social support subtypes and self‐efficacy, that influence the psychosocial adjustment were analysed using Cox's regression. Of the factors that influenced the adjustment groups after adjusting for time, the following subtypes of social support were found to influence the patients' adjustment: the patients' psychosocial adjustment increased by 0.4 when the level of medical staff support increased by 1 (Exp[B] = 1.04, P = 0.007), and adjustment decreased by 0.3 when the level of family support increased by 1 (Exp[B] = 0.97, P < 0.001). As medical staff support who have expertise exert more of an influence on the psychosocial adjustment of ostomy patients than self‐efficacy and family support, psychosocial adjustment programmes that reflect this and nurses specialised in care for ostomy patients are required.

Keywords: ostomy, psychosocial adjustment, self‐efficacy, social support

1. INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer is the second most common cancer after gastric cancer in South Korea, and the incidence of colorectal cancer has shown a continuously increasing trend.1 Moreover, the 10‐year survival rate increased by 19% from 51.8% in 1993‐1995 to 70.8% in 2006‐2010.1 The early detection of colorectal cancer, the development of various treatment methods, and the establishment of a standardised therapy have all contributed to the increase in the survival rates of colorectal cancer patients.2 Increased survival rates suggest that the perception of viewing cancer as an incurable disease should be changed, and it should rather be considered a chronic disease that requires sustained care and management.3

Among the various subtypes of colorectal cancer, stomas are usually formed through ostomy in cases of rectal cancer located closer to the anus.4 Ostomy patients have to endure the difficult treatments for cancer, including surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy, as well as significant psychological distress, physical pain, and medical treatments that interfere with daily living and decrease their quality of life.5, 6, 7 Moreover, ostomy patients must face significant adjustments as a consequence of their disease. Most significantly, the new excretion method may interfere with their daily living and increase the financial burden on their family, leaving these patients at risk of higher levels of negative emotions compared with other cancer patients.8 Additional ageing‐related problems may also arise with the increase in the life expectancy and thus the life‐span of ostomy patients.9, 10 Indeed, after ostomy patients are discharged from the hospital, they will require continued care for some of their health problems. Furthermore, as ostomy patients' adjustment will likely change over time, their adjustment will necessitate their continued engagement with health care professionals.

This engagement will require that ostomy patients not be merely treated as individuals who are defined by their stomas but rather should be understood from a more holistic perspective that considers the fact that they have survived cancer. Indeed, evidence suggests the importance of multidisciplinary support in order to improve patients' psychosocial adjustment and quality of life.3, 11

Previous studies have demonstrated that social support—particularly medical staff support—is a major determinant of the psychosocial adjustment of ostomy patients.12 Moreover, studies have verified the effects of patient education, typically provided by medical staff, on stoma self‐management.13 These educational effects can be further enhanced with the addition of familial and community support that is concurrent with the education provided by medical staff on the self‐management of stomas.11, 14

Particularly in Korea, where Confucian culture emphasises the importance of familial ties, familial support is an important factor that influences ostomy patient adjustment.15 Although such familial support has been observed to be high immediately after surgery,16 it is subject to change during significant crises that arise as the disease progresses. It is thus necessary to investigate the influence of familial support on ostomy patients longitudinally. Moreover, in South Korea, once the brief education from medical experts is over, the responsibility of stoma management is often transferred to the patients or their families, and this could result in these patients developing psychological problems.17 Therefore, predicting how the duration of familial and medical support would aid in the psychosocial adjustment of ostomy patients would contribute to the development of effective strategies to aid the continued adjustment of ostomy patients.

In order to support the psychosocial adjustment, patients will need to come to terms with the changes in their body image post‐surgery and perform effective stoma self‐management, including understanding the new defecation method, faeces management, use of ostomy pouches, colostomy irrigation, and dietary regulation.14 Ostomy patients will need to feel self‐efficacious in their ability to integrate the new physical changes post‐ostomy into their healthy body and competently maintain good care of their stomas in order to ensure successful and effective self‐management and adjustment.18

Such self‐efficacy over stomas is an important factor that influences the self‐care behaviours of colostomy patients. Indeed, belief in one's self‐efficacy was found to increase when patients could independently perform self‐care, including stoma management.19 Moreover, self‐efficacy over stomas was found to be a major predictor that relieves the burden of stomas and promotes psychosocial adjustment in colostomy patients.14, 18, 20

Various South Korean studies have investigated the psychosocial adjustment of ostomy patients.20, 21 However, most previous studies have been conducted on acute patients immediately post‐surgery, and very few studies have investigated whether adjustment is influenced by disease duration. As adjustment is heavily influenced by time, it necessitates statistical adjusting for time and the analysis of determining factors that are time‐dependent. Adjustment is a variable that is much influenced by time. In studying adjustment, it might be better to use longitudinal research, which requires time‐calibrated investigation and an analysis of factors that change over time. However, this study uses cross‐sectional research that is very meaningful as it can predict future developments in relation to adjustment by applying the time‐dependent Cox regression analysis. Identifying factors that affect adjustment over time and then predicting when adjustment‐related changes are made would greatly help develop an intervention programme that contributes to the better adjustment of ostomy patients.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design

This study is a descriptive survey study that aims to investigate social support, self‐efficacy, and the psychosocial adjustment of ostomy patients that have received surgical treatment for colorectal cancer. It aims to investigate the factors that influence the patient psychosocial adjustment through survival analysis that statistically adjusts for time.

2.2. Sample

Ostomy patients were sampled from a university hospital in B City, five chapters of the Korean Ostomy Association, and one ostomy patient group in S City. Overall, 150 patients were recruited between December 1, 2017, and March 26, 2018 after providing informed consent ensuring that they understood the purpose of the study and that their participation in the study was voluntary. Of these patients, 25 participants were excluded from the final sample as their data contained insincere responses, and thus, the final sample included 125 participants.

As its subjects, this study selected those who had received ostomy over 6 months before with reference to Sharp et al's research22 which found physical disorders following ostomy begin to substantially remove 6 months after the operation. In a similar vein, there is prior study14 on post‐colostomy adjustment that worked on patients who had received the surgery over 6 months previously. The following selection criteria were used:

Inclusion criteria:

Ostomy patients who had received ostomy surgical treatment of colorectal cancer at least 6 months after ostomy surgery.

Those who can communicate and can understand and respond to the questionnaires.

Exclusion criteria:

Participants who cannot understand the questions provided and cannot respond to them.

Those who have cognitive impairment.

2.3. Power analysis

The sample size estimate was calculated using the PASS 15.0 programme (NCSS, Kaysville, Utah). A Cox regression of the log hazard ratio on a covariate with a SD of 1.00 based on a sample of 62 observations achieves 80% power at a 0.15 significance level to detect a regression coefficient equal to 0.45.

The sample size was adjusted as a multiple regression of the variable of interest on the other covariates in the Cox regression is expected to have an R‐Squared of 0.16. The sample size was adjusted for an anticipated event rate of 0.50.

2.4. Ethical considerations

The present study was performed after obtaining approval from the institutional review board of Dong‐A University Hospital located in the B City of Korea (IRB No. DAUHIRB‐17‐216). The researcher explained the relevant aspects related to research ethics, such as the purpose of the study, methods, benefits, risks, and protection of privacy, to ostomy patients who satisfied the selection criteria. Those who voluntarily consented to participate were asked to complete self‐report questionnaires.

2.5. Instruments

2.5.1. Social support

The social support scale developed by Tae23 was used. The tool consists of a total of 16 questions, including two subdomains, family support and medical staff support, each evaluated with eight items. Each item was scored on a 5‐point Likert scale, from a score of 1 corresponding to “never” to a score of 5 corresponding to “always.” The total score ranged between 16 and 80, with higher scores indicating higher levels of social support. This instrument was reliable, with Cronbach's α of 0.82 for family support and 0.84 for medical staff support in Tae's study.23 In the present study, Cronbach's α was 0.94 for overall social support, 0.95 for family support, and 0.96 for medical staff support.

2.5.2. Self‐efficacy

This study used An's tool24 to measure the self‐efficacy of ostomy patients. The instrument includes a total of 17 items: three questions on maintenance of skin conditions, two on the replacement of tools, six on dietary regulation, one on clothing, one on exercise, one on participation in self‐help groups, one on emergency measures, one on sleep, and one on stress management. The score for each question ranges between 10, indicating “not confident at all,” and 100, indicating “very confident.” The total score thus ranges between 170 and 1700, with higher scores indicating higher levels of self‐efficacy. The reliability of the tool was 0.94 in An's study.24 In the present study, Cronbach's α was 0.86.

2.5.3. Psychosocial adjustment

This study used the Ostomy Adjustment Inventory‐23 (OAI‐23), which was originally developed by Simmons et al25 to measure the level of psychosocial adjustment of ostomy patients after obtaining the original authors' approval. For this study, the tool was translated and back‐translated. Before the questionnaire was distributed to the participants, two professors of nursing and two wound ostomy continence nurses (WOCNs) verified the validity of the questions. Through preliminary surveys, the items that did not fully convey the intended meaning were supplemented and edited. The tool consists of a total of 23 items on four subdomains. There are 10 questions assessing acceptance of stomas, 6 assessing anxiety regarding stomas, 4 on social participation, and 3 on anger regarding stomas. Each item was rated on a 5‐point Likert score, from a score of 0 indicating “strongly disagree” to a score of 4 indicating “strongly agree.” The total score for the tool ranges between 0 and 92, and higher scores indicate higher levels of psychosocial adjustment in ostomy patients. At the time of development, the tool's Cronbach's α was 0.93 in Simmons et al's study,25 and Cronbach's α was 0.88 in this study.

2.6. Statistics analyses

SPSS 20.0 programme (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) was used for the data analysis in this study. For the general characteristics of the participants, frequency and percentage were calculated for gender, which was a nominal variable. Continuous variables, including age, ostomy care duration, social support, self‐efficacy regarding stomas, and psychosocial adjustment, were assessed in terms of mean, SD, kurtosis, and skewness. As the patients' psychosocial adjustment is influenced by the duration of ostomy care, Cox's regression was performed after adjusting for time. For Cox's regression, the score for adjustment, which was a dependent variable, was a binary variable (0 for patients with a score below 40 who have not adjusted and 1 for patients with scores of 40 and above who have adjusted) based on the study of Cheng et al,26 who classified scores below 40 as low, between 40 and 59 as average, and 60 and above as high. Moreover, to confirm time‐dependent variables, Pearson's correlation coefficients were calculated for ostomy care duration and study variables. Cox's time‐dependent regression was performed only for the statistically significant variables. Based on the statistical findings, a hazard ratio (HR) with time was calculated for the significant variables.

3. RESULTS

3.1. General characteristics of the participants

There were 60 men (48%) and 65 women (52%) in the sample. The mean age of the participants was 66.6 (±11.06) years. The mean ostomy care duration was 128.7 (±119.61) months. The mean total score for medical staff support was 22.2 (±8.51), and the mean total score for family support was 33.6 (±6.90). The score for self‐efficacy was 1253.3 (±227.03), and the score for psychosocial adjustment was 60.0 (±13.55). Regarding psychosocial adjustment, 100 (80%) participants were found to have adjusted (adjustment group), and 25 (20%) were found to have not adjusted (non‐adjustment group; Table 1). As the requirement for an absolute value of skewness below 3 and kurtosis below 10 was satisfied for the continuous variables, the variables were found to have normal distributions.27

Table 1.

General characteristics of ostomy patients (N = 125)

| Variable | n (%) | Mean | SD | Item mean | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 60 (48.0) | ||||||

| Female | 65 (52.0) | ||||||

| Age | 66.6 | 11.06 | −0.19 | −0.70 | |||

| Ostomy care duration (mo) | 128.7 | 119.61 | 0.69 | −0.72 | |||

| Social support | |||||||

| Medical staff support | 22.2 | 8.51 | 3.40 | 1.06 | −0.54 | −0.37 | |

| Family support | 33.6 | 6.90 | 4.20 | −0.86 | −1.16 | 1.03 | |

| Self‐efficacy | 1253.3 | 227.03 | 73.72 | 13.35 | −0.88 | 0.59 | |

| Psychosocial adjustment | 60.0 | 13.55 | 2.22 | 0.59 | 0.31 | 0.36 | |

| Adjustment group (≥40) | 100 (80.0) | ||||||

| Non‐adjustment group (<40) | 25 (20.0) | ||||||

3.2. The influence of social support and self‐efficacy in the adjustment group

After controlling for time, the adjustment group were observed to be significantly influenced by the support of medical staff and family, whereas self‐efficacy was not found to be statistically significant. In particular, psychosocial adjustment increased by 0.04 when the level of medical staff support increased by 1 (Exp[B] = 1.04, P = 0.007), and the adjustment decreased by 0.03 when the level of family support increased by 1 (Exp[B] = 0.97, P < 0.001; Table 2).

Table 2.

The effect of medical team support, family support, and self‐efficacy between the adjustment group and the non‐adjustment group through Cox's regression (N = 125)

| Variable | B | SE | Wald (df) | P | Exp (B) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical staff support | 0.04 | 0.10 | 7.40 (1) | 0.007 | 1.04 |

| Family support | −0.04 | 0.20 | 4.38 (1) | < 0.001 | 0.97 |

| Self‐efficacy | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.56 (1) | 0.453 | 1.00 |

3.3. Relationship between medical staff support, family support, self‐efficacy, and ostomy care duration

Table 3 shows correlations between time and some variables, which were determined in order to know if the variables are time‐dependent.

Table 3.

Correlation medical staff support, family support, self‐efficacy, and ostomy care duration (N = 125)

| Medical staff support r (P) | Family support r (P) | Self‐efficacy r (P) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medical staff support | — | ||

| Family support | 0.38* (<0.001) | — | |

| Self‐efficacy | 0.11 (0.235) | 0.18* (0.045) | — |

| Ostomy care duration | −0.22* (0.014) | −0.03 (0.705) | 0.16 (0.081) |

Statistically significant.

The relationship between each variable and ostomy care duration was assessed, and a significant negative correlation between medical staff support and ostomy care duration was found (r = −0.22, P = 0.014). This is considerably meaningful as medical staff support was found as a time‐dependent variable that has significant correlations with ostomy care duration, despite the correlation coefficient not being high at 0.3 or below.

Although family support was found to have a positive correlation with self‐efficacy (r = 0.18, P = 0.045), family support and self‐efficacy did not have a statistically significant relationship with ostomy care duration (Table 3).

3.4. The time‐dependent relationship between medical staff support and the psychosocial adjustment group

Based on Cox's regression analysis, it was found that medical staff support and family support was significant, and in addition, medical staff support and ostomy care duration were significantly correlated.

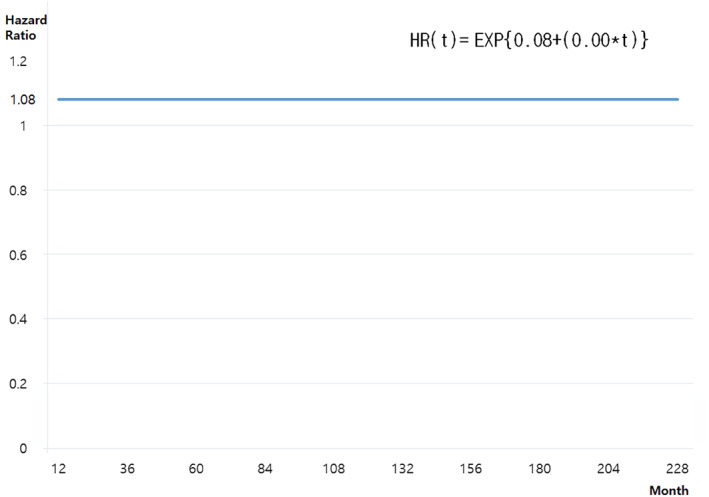

A time‐dependent covariate regression analysis of medical staff support and family was performed. The analysis demonstrated that medical staff support is a time‐dependent variable in the psychosocial adjustment group of ostomy patients (Exp[B] = 1.00, P = 0.004; Table 4). When the level of family support was consistent, the HR of medical staff support stayed consistent at 0.08 over time, constantly influencing the adjustment group (Figure 1). This indicates that medical staff support is consistently important in the adjustment group of ostomy patients.

Table 4.

Verification of medical team support variable through Cox's time‐dependent regression (N = 125)

| B | SE | Wald | P | Exp (B) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time covariance | 0.00 | 0.00 | 8.13 | 0.004 | 1.00 |

| Medical staff support | 0.08 | 0.02 | 14.19 | < 0.001 | 1.08 |

| Family support | −0.04 | 0.02 | 5.20 | 0.023 | 0.96 |

Figure 1.

Time‐dependent changes in medical staff support that influence psychosocial adjustment

4. DISCUSSION

This study was conducted to investigate the relations between social support, self‐efficacy, and psychosocial adjustment in ostomy patients who underwent surgical treatment for colorectal cancer as well as to investigate the determinants that influence patient psychosocial adjustment after adjusting for time.

Among the subtypes of social support for the participants, the score for medical staff support was 3.38 of 5 on average, whereas that for family support was 4.19; therefore, the level of family support was higher than that of the medical staff. When the factors that influence the adjustment group were tested after adjusting for time, medical staff support was found to increase the patients' psychosocial adjustment, while the level of adjustment decreased with increases in the family's support. Although many studies found that family support positively influences the adjustment and quality of life of ostomy patients,19, 28 this study found that the patients' high level of support from their families decreased their psychosocial adjustment when time was statistically adjusted.

Similar to a study that found lower quality of life in cancer patients receiving help from their children,29 and another study where family support did not influence management of cancer at all,30 the participants of this study experienced adverse effects of treatment and difficulties from physical and psychological weakening, and their high family support from spouses and children's care was found to interfere with their successful adjustment.

Moreover, considering that many of the participants received an ostomy 10 years ago on average, inappropriate family support could have bothered the patients or lowered their self‐esteem, with increases in the ostomy care duration.31 In particular, sexual problems in ostomy patients have been highlighted in multiple studies as an important issue in their spousal relationships.32, 33

Inappropriate family support may cause considerable burden or guilt in ostomy patients rather than being perceived as quality emotional care provided through interaction with the family.16 Moreover, the study sample consisted mostly of elderly patients aged 66.57 years on average, and their fight against cancer may have imposed a burden on the patients that may lead to burnout, breakdown of their familial role, or financial hardship for children or spouses when the patients themselves cannot provide anything to the family members any more. Such negative responses may be explained by the fact that, in Korean culture, the Confucian ideal of the head of the household taking responsibility for the entire family is still prevalent.15

Furthermore, family members, who did not previously have much interest in the patients, may have provided more than enough support as the patients received cancer treatment and ostomy, and that may have acted as a psychological burden on the patients. In a phenomenological study conducted on young adults who had undergone an ostomy 4 years prior to the study,17 patients were comforted when their family helped with changing ostomy pouches, while at the same time, these patients did not want to receive more support than necessary. This finding is arguably consistent with, and may help explain, the current results.

Another phenomenological study on patients who received urostomy28 also demonstrated the negative aspects of inappropriate family support; the patients wanted their family to accept them as they are instead of pitying them, and the patients also reported that relying on family members makes them feel as if they are being pitied and lowers their self‐esteem or makes them feel stigmatised. Considering that the items on the social support measure used in this study quantifies the level of intimacy between family members, relationship with family, and family support, it appears the participants are receiving sufficient amounts of family support. However, the quality of support may not be great despite the quantity, thus negatively influencing the patients' long‐term psychosocial adjustment.

Accordingly, considering the recent social changes in Korea, where households comprising of only elderly couples and single households are increasing, the level of family support and family relationship should be approached through multidisciplinary perspectives in order to perform a continued re‐evaluation to positively influence the adjustment of ostomy patients.

Recalla et al12 reported that negative responses to stomas could be improved with time, and Neuman34 reported that quality of life and emotional, cognitive, and social functions did not differ between patients with and without stomas 8 years after an ostomy. This previous research indicates that ostomy patients naturally achieve successful psychosocial adjustment with time, although the present study found that medical staff support should be maintained at the same level as that provided immediately after ostomy in order to ensure the successful psychosocial adjustment of patients. This is because new complications or those that do not resolve with time, such as skin conditions around stomas, leaking of faeces, gas or odour production, and sexual issues, require help from experts, as is the case for loss of cognitive function or decreased physical function because of ageing.12, 16, 28

Previous studies have emphasised the importance of support and the role of nurses for urostomy or ostomy patients even before surgery.28, 35 Moreover, a recent study reported that stoma management education provided by nurses immediately after surgery is too short for patients to fully understand the contents even though it was still considered helpful.36 Multiple studies have also emphasised that programmes for the continued management of stomas provided by medical staff are required even after discharge, which is consistent with the current findings and recommendations.12, 17, 19

As rapidly evolving new medical technologies now provide more information, medical staff is required to provide support and sufficient education on new medical technologies and ostomy goods. However, in Korea, overcrowding at general hospitals has led to problems such as medical staff shortages and reduced treatment times. Furthermore, as the certification of the WOCNs has not been legally settled yet in South Korea, there is a lack of the certified WOCNs for stomas, and thus, specialised nurses are limited to a narrow scope of work. In order to solve such problems, active policy improvements and social changes are required, including the introduction of the WOCN for stomas who can educate patients on diseases or changes after surgery using appropriate, clear vocabulary for relevant patients. If patients can receive more accurate, individually tailored information through such specialised nurses for stomas, physical changes after surgery or treatment will not come as surprises, and a positive psychosocial adjustment will be encouraged instead. For ostomy patients who received surgical treatment for colorectal cancer, this study investigated their social support, including medical staff support and family, self‐efficacy, and psychosocial adjustment and confirmed factors that influence their psychosocial adjustment after statistically adjusting for time. In order to overcome the limitations of cross‐sectional survey research, a time‐dependent Cox's regression was used to assess medical staff support as a time‐dependent variable. Moreover, this study is significant in that it found the continued need for medical staff support in ostomy patients and provided basic knowledge for nursing interventions to improve such patients' psychosocial adjustment.

5. CONCLUSIONS

This study was conducted to test the factors that influence and aid the psychosocial adjustment of ostomy patients and confirm which factors are influencing their psychosocial adjustment after statistically adjusting for time through survival analysis.

Regarding factors that influence the psychosocial adjustment group of ostomy patients after statistical adjustment for time, the following subtypes of social support were found to influence the adjustment: when medical staff support increased, patients' psychosocial adjustment increased, whereas the adjustment decreased with increases in family support.

Moreover, medical staff support was found to consistently influence psychosocial adjustment of ostomy patients over time. As medical staff support with expertise exerts more significant influences on the psychosocial adjustment of ostomy patients than factors such as self‐efficacy and family support, psychosocial adjustment programmes that reflect this finding are required. Moreover, the scope of the role of specialised nurses for stomas should be expanded, and the system of specialised nurses should become more widespread in order to increase capacity to better accommodate for such difficulties.

5.1. Study limitations

As this study was conducted on 125 randomly selected ostomy patients who underwent surgical treatment for colorectal cancer, any generalisation of the findings to all ostomy patients should be met with caution. Moreover, although demented patients or those with a history of psychiatric illnesses were excluded, the patients were elders, with the mean age of 66.57 years. Therefore, complex factors that can influence psychosocial adjustment, the final dependent variable, may have been present. Furthermore, in contrast to previous findings, self‐efficacy did not show a statistically significant relationship with psychosocial adjustment. Accordingly, its correlation with the psychosocial adjustment of ostomy patients should be confirmed again in future studies.

Nam KH, Kim HY, Kim JH, Kang K‐N, Na SY, Han BH. Effects of social support and self‐efficacy on the psychosocial adjustment of Korean ostomy patients. Int Wound J. 2019;16(Suppl. 1):13–20. 10.1111/iwj.13038

REFERENCES

- 1. Korea Center Cancer Registry, National Cancer Center . Annual report of cancer statistics in Korea in 2015. Gyeonggi, Korea: Ministry of Health and Welfare; 2017.

- 2. Oblak I, Petric P, Anderluh F, Velenik V, Fras PA. Long term outcome after combined modality treatment for anal cancer. Radiol Oncol. 2012;46:145‐152. 10.2478/v10019-012-0022-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lee EK, Ryu EJ, Kim KH. Structural equation modeling on adjustment of cancer patients receiving chemotherapy. J Korean Oncol Nurs. 2011;11:101‐107. 10.5388/jkon.2011.11.2.101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Carmel JE, Colwell JC, Goldberg MT. Ostomy Management. Philadelphia, PA: WOCN Nurses Society: Wolters Kluwer; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shin JH, So HS, Kim EA. Influence of post‐traumatic stress disorders on quality of life among patients with ostomy: focused on the mediating effect of resilience. Korean J Adult Nurs. 2017;29:657‐666. 10.7475/kjan.2017.29.6.657. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jun SY, Song YS. Living with a colostomy: a phenomenological study. Korean J Adult Nurs. 2017;29:579‐586. 10.7475/kjan.2017.29.6.579. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ciorogar G, Zaharie F, Ciorogar A, et al. Quality of life outcomes in patients living with stoma. Hum Vet Med. 2016;8:137‐140. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nam SY, Lee HK, Kim S, Lee RA. Factors affecting body image and sexual life for the colorectal cancer patients with stoma. Asian Oncol Nurs. 2018;18(1):10. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yeom JW, Shin SJ. Factors related to nutritional status among older adults with an ostomy. J Korean Gerontol Nurs. 2017;19:39‐47. 10.17079/jkgn.2017.19.1.39. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Reynaud SN, Meeker BJ. Coping styles of older adults with ostomies. J Gerontol Nurs. 2002;28:30‐36. 10.3928/0098-9134-20020501-08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Figueiredo PA, Alvim NAT. Guidelines for a comprehensive care program to ostomized patients and families: a nursing proposal. Rev Latino‐Am Enfermagem. 2016;24:1‐8. 10.1590/1518-8345.0507.2694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Recalla S, English K, Nazarali R, Mayo S, Miller D, Gray M. Ostomy care and management. A systematic review. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2013;40:489‐500. 10.1097/WON.0b013e3182a219a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Grant M, McCorkle R, Hornbrook MC, Wendel CS, Krouse R. Development of a chronic care ostomy self‐management program. J Cancer Educ. 2013;28:70‐78. 10.1007/s13187-012-0433-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Simmons KL, Smith JA, Bobb KA, Liles LL. Adjustment to colostomy: stoma acceptance, stoma care self‐efficacy and interpersonal relationships. J Adv Nurs. 2007;60:627‐635. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yang JH. Adjustment experiences of patients with permanent colostomy. Qual Res. 2012;13:168‐179. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Song KS, Park YS. A study on quality of life and related factors of ostomates. J Korean Acad Nurs. 1999;29:817‐828. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sinclair LG. Young adults with permanent ileostomies: experiences during the first 4 years after surgery. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2009;36:306‐316. 10.1097/WON.0b013e3181a1a1c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bekkers MJ, van Knippenberg FC, van Dulmen AM, van den Borne HW, van Berge‐Henegouwen GP. Survival and psychosocial adjustment to stoma surgery and nonstoma bowel resection: a 4‐year follow‐up. J Psychosom Res. 1997;42:235‐244. 10.1016/S0022-3999(96)00288-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gautam S, Koirala S, Poudel A, Paudel D. Psychosocial adjustment among patients with ostomy: a survey in stoma clinics, Nepal. Nursing (Auckl). 2016;55:13‐21. 10.2147/NRR.S112614. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kim KM, Baek ES, Kang NH, Yoon KE, Bae NY, Cha BK. Effects of self‐efficacy promoting programs on self‐efficacy, self‐care behavior and psychosocial adaptation in patients with a colostomy. J Korean Acad Fundam Nurs. 2007;14:288‐296. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cha BK, Baek ES. Psychosocial adaptation and related factors in patients with a permanent colostomy. Korean Acad Fundam Nurs. 2009;16:506‐514. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sharpe L, Patel D, Clarke S. The relationship between body image disturbance and distress in colorectal cancer patients with and without stomas. J Psychosom Res. 2011;70:395‐402. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tae YS. Study on the Correlation between Perceived Social Support and Depression of the Cancer Patients [unpublished master's thesis]. Seoul, South Korea: Ehwa Womans University; 1986.

- 24. An JY. Effect of Self Efficacy Enhancing Individual Education on Self‐care Behavior of Ostomates [unpublished master's thesis]. Seoul, South Korea: Seoul National University; 2006.

- 25. Simmons KL, Smith JA, Maekawa A. Development and psychometric evaluation of the ostomy adjustment Inventory‐23. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2009;36:69‐76. 10.1097/WON.0b013e3181919b7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cheng F, Meng AF, Yang LF, Zhang YN. The correlation between ostomy knowledge and self‐care ability with psychosocial adjustment in Chinese patients with a permanent colostomy: a descriptive study. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2013;59:35‐38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kline RB. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2011.

- 28. Villa G, Manara DF, Brancato T, et al. Life with a urostomy: a phenomenological study. Appl Nurs Res. 2018;39:46‐52. 10.1016/j.apnr.2017.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Esbensen BA, Osterlind K, Roer O, Hallberg IR. Quality of life of elderly persons with newly diagnosed cancer. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2004;13:443‐453. 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2004.00546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cicero V, Lo Coco G, Gullo S, Lo Verso G. The role of attachment dimensions and perceived social support in predicting adjustment to cancer. Psychooncology. 2009;18:1045‐1052. 10.1002/pon.1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ogilvie AD, Morant N, Goodwin G. The impact of bipolar depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;7:25‐32. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ceylan H, Vural F. Living with stoma—a phenomenological study. J Nurs Res Pract. 2017;1:6‐12. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Andersson G, Engström Å, Söderberg S. A chance to live: women's experiences of living with a colostomy after rectal cancer surgery. Int J Nurs Pract. 2010;16:603‐608. 10.1111/j.1440-172X.2010.01887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Neuman HB, Patil S, Fuzesi S, et al. Impact of a temporary stoma on the quality of life of rectal cancer patients undergoing treatment. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:1397‐1403. 10.1245/s10434-010-1446-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Burch J. Optimal support systems for patients with stomas—an opinion piece. Nursing (Auckl). 2014;4:55‐64. 10.2147/NRR.S36676. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ang SGM, Chen HC, Siah RJC, He HG, Klainin‐Yobas P. Stressors relating to patient psychological health following stoma surgery: an integrated literature review. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2013;40:587‐594. 10.1188/13.ONF.587-594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]