Abstract

Clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) for venous leg ulcer (VLU) management recommend below‐knee compression to improve healing outcomes after calculating the ankle‐brachial pressure index (ABPI) to rule out significant arterial disease. This systematic scoping review aimed to complete a qualitative and quantitative content analysis of international CPGs for VLU management to determine if consensus existed in relation to recommendations for compression application based on an ABPI reading and clinical assessment. Our review shows that there is a lack of consensus across 13 VLU CPGs and a lack of clear guidance in relation to the specific ABPI range of compression therapy that can be safely applied. An area of uncertainty and disagreement exists in relation to an ABPI between 0.6 and 0.8, with some guidelines advocating that compression is contraindicated and others that there should be reduced compression. This has implications in clinical practice, including when it is safe to apply compression. In addition, the inconsistency in the levels of evidence and the grades of recommendation makes it difficult to compare across various guidelines.

Keywords: ankle‐brachial pressure index (ABPI), clinical practice guidelines, consistency, scoping review, venous leg ulcers

1. INTRODUCTION

People with chronic venous insufficiency (CVI) are prone to active venous leg ulcers (VLU) because of persistent high blood pressure in varicose veins. Prolonged high pressure leads to low‐level chronic inflammation in the surrounding tissues and precipitates ulcer formation. CVI affects 2 people per 1000 of the general population in Australia, and of those, 20 per 1000 will develop an active ulcer.1 One in three individuals with CVI experience more than 10 episodes of ulceration in their lives, commonly with protracted healing and recurrence because of underlying pathophysiology.1 An age‐related VLU is the most common cause of lower limb ulceration in the community settings in developed countries, with incidences between 1.5 and 3.0 in 1000 in people aged 65 and younger. Prevalence increases with age to reach 20 in 1000 people aged over 80 years.2 Sustained healing is a major challenge that has a considerable impact on individual health and quality of life. Estimated health care costs relating to VLU treatment in Australia exceed $3 billion/year.3, 4 A recent study from the United Kingdom reported that the mean NHS cost of VLU care over 1 year was £7600 per wound, which was much higher for unhealed wounds.5 With an ageing population and the growing epidemics of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and obesity, this burden is expected to rise dramatically. For example, in the United Kingdom, the number of new VLUs has been estimated to increase to 170 000 in 2017 to 2018 and was predicted to cost approximately £1·3 billion during the first year of treatment.6

Compression therapy is the current best practice for VLU management and prevention.7 Clinical practice guidelines (CPGs)8 recommend that compression therapy be applied only in the absence of arterial complications. The ankle‐brachial pressure index (ABPI) and/or toe brachial pressure index (TBPI) are calculated to rule out significant arterial disease.9

ABPI is widely used by health professionals for screening, diagnostic, and monitoring purposes in VLU and peripheral arterial disease (PAD) management. In clinical practice, hand‐held Doppler ultrasonography is used to measure ABPI prior to compression application to rule out marked arterial disease.10 A Doppler ultrasound produces accurate systolic pressure readings for ABPI measurements, with a reported strong interrater reliability (intraclass correlation coefficient, 0.93‐0.99).11 However, in patients with renal disease and diabetes mellitus, these measures may be unreliable because of the arterial incompressibility as a result of calcification of arterial walls.12 The ABPI is calculated as “the ratio of arm systolic pressure, taken as the best non‐invasive estimate of central systolic pressure, and the highest ankle systolic pressure, as measured in each of the three named vessels at the ankle, for each limb.”12

People with VLUs are usually treated in the community setting and often managed in general practice by general practitioners (GPs) and Practice Nurses3 and referred to specialist wound clinics if clinicians assess the wound healing to be protracted. This clinical judgement is often subjective.3 Evidence‐based CPGs8, 13 recommend below‐knee compression to improve healing outcomes, assessment of ABPI with a Doppler or a venous duplex scan to diagnose accurately and exclude arterial insufficiency prior to compression application, and specialist referral within 3 months of diagnosis or first visit and sooner for patients with comorbid conditions such as diabetes.

In patients with chronic VLUs, ABPI must be interpreted with caution as it may under‐represent the degree of arterial disease in the lower extremity in patients with low central systolic pressure or where there is PAD in the upper extremity.14 ABPI contraindications include a high level of pain in lower limbs and deep vein thrombosis as the ABPI assessment procedure may lead to thrombus dislodgement and acute embolism.15

Evidence‐based CPGs are designed to improve the quality of care and reduce practice variation by providing graded recommendations based on the best available evidence. They are intended as instruments of knowledge transfer to support decision‐making by physicians, other health professionals, and patients in clinical practice.1, 16 Although regularly updated, the level of evidence may vary and contain conflicting information, which may interfere with implementation1 and reduce utilisation in clinical practice.3 The aim of this study was to analyse the existing international CPGs for VLU management on the recommendations for compression based on ABPI readings and clinical assessment.

2. METHODS

2.1. Objectives

This review aimed to complete a qualitative and quantitative content analysis of international VLU CPGs in VLU to determine if consensus existed in relation to recommendations for compression application based on an ABPI reading and clinical assessment.

2.2. Eligibility criteria

CPGs or best practice recommendations (BPRs) for VLU were considered eligible for inclusion in this review provided that they:

were explicitly described as a CPG or BPR by authors;

were original (ie, not derived from an amalgamation of other CPGs from other organisations);

had a dedicated VLU section in the event that the guideline covered wounds of multiple aetiologies or an umbrella condition such as CVI; and

were published or had an update published between the years 2000 and 2018.

There were no language restrictions.

2.3. Information sources

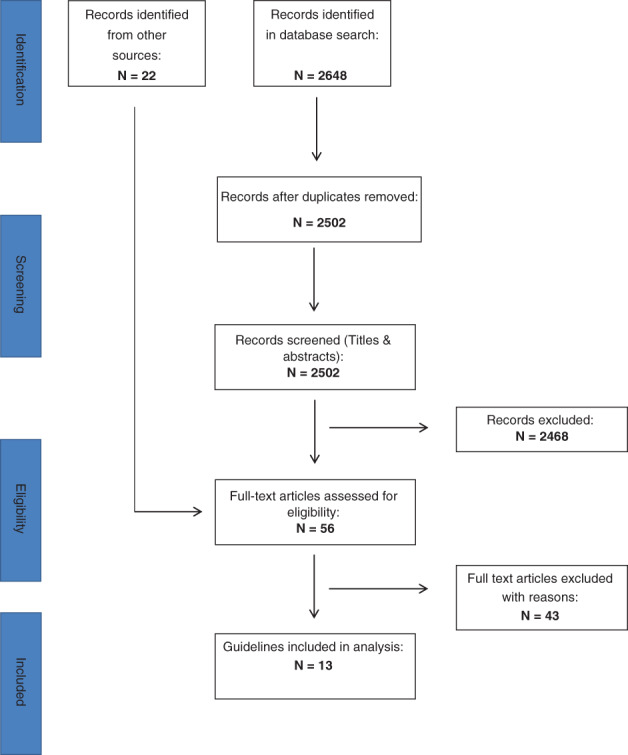

CPGs or BPRs were sourced from an article by Andriessen et al17 through searches of Scopus (inception to present) and PubMed (2000 to present) using the search strategy outlined in Figure 1 or were provided by the authors of this review.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Chart

2.4. Study selection

Titles and abstracts were screened by individual reviewers (C.D.W.; G.G.; K.C., & J.D.I.), and those that were clearly not CPGs or BPRs were eliminated. A second reviewer (K.C. or J.D.I.) located the full text of any titles and abstracts that were marked as unclear and excluded them if not CPGs or BPRs. Full texts of titles and abstracts marked as unclear and in languages other than English were screened by a single reviewer (J.D.I.) using Google Translate where necessary and were either excluded or included for further screening.

Potentially eligible full‐text articles were then screened for inclusion by two independent reviewers (J.D.I. or K.C.) according to the inclusion criteria. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion between the two reviewers. Because of limited resources, full‐text articles in languages other than English were screened for inclusion by a single reviewer only.

2.5. Data extraction

A pre‐designed data extraction form was revised and refined after an initial extraction exercise by two reviewers (V.T. & J.D.I.) using three eligible sets of guidelines. Three independent review authors (K.C., V.T., and J.D.I.) extracted relevant data. Discrepancies in the extracted data were resolved by discussion between the three authors. Because of limited resources, data from guidelines written in a language other than English were extracted by a single reviewer only.

Data items for inclusion in the study included methodology used to create the CPG; target population; recommended method for measuring ABPI; designated personnel to carry out the assessment; barriers to accurate reading; indications, contraindications, and precautionary recommendations for compression therapy in the context of ABPI readings; and recommendations for specialist referral. Reported data on recommendations for reassessment of ABPI were also extracted.

2.6. Quality assessment

As this is a scoping review, it was not considered necessary to carry out a quality appraisal on included guidelines.

2.7. Synthesis

Qualitative and quantitative content analyses18 were used to synthesise data extracted from included CPGs in this review. The main themes that we identified in qualitative analysis include1: the description of the systematic review methodology,2 evidence rating,3 ABPI measurement recommendations,4 ABPI interpretation,5 ABPI and compression indication,6 ABPI and compression contraindication,7 ABPI and precautions to compression therapy, and8 ABPI and referral to specialist services. The unit of qualitative analysis was a message unit, for example, messages related to the ABPI measurement. Quantitative content analysis was focused on the ABPI as a score, which was the unit of observation. Extracted ABPI measures were grouped according to the message attached to them, for example, if ABPI score < 0.5, compression is contraindicated.

3. RESULTS

3.1. CPG selection

Database searches resulted in the identification of N = 2648 records. After removal of duplicates, N = 2502 titles and abstracts were screened for eligibility. Of these, N = 34 were retained for full‐text screening. These retained articles were supplemented by N = 22 full‐text articles provided by the authors or obtained from an article by Andriessen et al17 (Figure 1).

Of these N = 56 full‐text articles, N = 43 failed to meet inclusion criteria (Table 1). Of the excluded full texts, 21 were not CPGs, and 17 were not original, that is, authors explicitly reported that other guideline sets had been used in their development. Ten of the excluded full texts were CPGs without a dedicated VLU section. One article19 was published prior to 2000 but simultaneously included as an update,20 and one guideline21 was already included as another publication.22 Eight of the articles failed to meet more than one inclusion criteria according to two different reviewers.

Table 1.

List of excluded studies

| Author/organisation | Year | Country of origin | Reason for exclusiona | Author/organisation | Year | Country of origin | Reason for exclusiona | Author/organisation | Year | Country of origin | Reason for exclusiona |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAWC | 2015 | USA | 2 | Crawford, P. E. & fields‐Varnado M. | 2013 | USA | 3 |

Mosti, G. et al. IUP |

2015 | USA | 1; 2 |

|

Ehresmann, U. et al. DGP |

2008 | Germany | 2 | Defloor, T. S. L. & Schoonhoven, L. | 2004 | Belgium | 1 | EWMA | 2003 | N/A | 1 |

| Aldeen, L. | 2007 | UK | 2 |

Edwards H. |

2013 | Australia | 1 | RNAO | 2007 (update) | Canada | 2 |

| Anderson, I. | 2012 | UK | 1 | Foy White‐Chu, E. & Conner‐Kerr, T.A | 2014 | USA | 1; 2 | DGP | 2004 | Germany | 2 |

|

Assenheimer, B. et al. ICW |

2013 | Germany | 1 |

Franks, P.J. EWMA |

2016 | N/A | 1; 2 |

Rabe, E. DGP |

2008 | Germany | 2 |

| Beldon, P. | 2011 | UK | 1 |

Fujimoto, M. A. Y. et al. Japanese Dermatological Association |

2016 | Japan | 3 |

Rabe, E. ESVS |

2008 | Belgium | 3 |

|

Bolton, L. WOCN |

2008 | USA | 1 |

Gallenkemper, G. et al. DGP |

2000 | Germany | 4 (2012 update) |

Rabe, E. et al. DGP |

2008 | Germany | 2 |

|

Bolton, L. et al. |

2006 | USA | 1; 2 |

Gloviczki, P. et al. SVS and the AVF |

2011 | USA | 1 |

Rüttermann, M. et al. Deutsch Gesellschaft für Wundheilung und Wundbehandlung e.v. & AWMF & Deutsch Gesellschaft für Pflegeweissenschaft |

2013 | Germany | 3 |

|

Bolton, L. L. et al. AAWC |

2014 |

USA |

2; 3 |

Gordillo, G. M. & Sen, C.K. |

2009 |

USA |

1; 3 |

Simms, W. |

2010 |

USA |

3 |

| Bonham, P. A. et al. | 2016 | USA | 2;3 | Kimmel, H.M. | 2013 | USA | 1 |

Tang, J. C. et al. WHS |

2012 | USA | 5 |

|

Burckhard, M. DGfW |

2012 | Germany | 2 |

Kirsner, R. S. WHS |

2016 | USA | 1 |

Widener, J. M. |

2015 | USA | 2; 3 |

|

Burrows, C. et al. CAWC |

2006 | Canada | 2 |

Kunimoto, B. et al. CAWC |

2001 | Canada | 1 |

Wilm, S. et al. DGP & DeGAM |

2010 | Germany | 2 |

| Cavorsi, J. et al. | 2006 | USA | 2 | Ligresti, C. & Passaro, I. | 2009 | Italy | 1 |

Wittens, C. ESVS |

2015 | Belgium | 3 |

| Cooper, M. A. et al. | 2015 | USA | 1 | Maessen‐Visch, M.B. & de Roos, K. | 2014 | Netherlands | 1 | ||||

| Corbett, L. Q. | 2012 | USA | 1 | McInnes, E. et al. | 2000 | UK | 1 |

Abbreviations: AAWC, Association for the Advancement of Wound Care; AVF, American Venous Forum; AWMF, Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften; CAWC, Canadian Association of Wound Care; DeGAM, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Allgemeinmedizin und Familienmedizin; DGfW, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Wundheilung und Wundbehandlung e.V.; DGP, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Phlebology; ESVS, European Society for Vascular Surgery; EWMA, European Wound Management Association; ICW, Initiative for Chronic Wounds; IUP, International Union of Phlebology; RNAO, Royal Nurses Association of Ontario; SVS, Society for Vascular Surgery; WHS, Wound Healing Society; WOCN, Wound Ostomy and Continence Nursing.

Exclusion criteria: 1 = Document is not a Clinical Practice Guideline or Best Practice Recommendation; 2 = Not an original Clinical practice Guideline or Best Practice Recommendation (explicitly derived from other guideline sets); 3 = Does not have a dedicated VLU section (eg, if the document is concerned with wounds in general or lower extremity venous disease); 4 = Published prior to 2000; 5 = Duplicate missed at initial screen.

3.2. Description of the included CPGs

We included 13 CPGs (Table 2): 322, 30, 32 from the United States; 2 each originated in of Germany,20, 31 Australia/New Zealand,8, 23 and Italy27, 28; and one guideline set each came from France,29 Switzerland,25 the Netherlands,33 and Scotland.13 All included CPGs except one23 were produced by a medical association or government organisation.

Table 2.

List of included guidelines

| Organisation/Author | Year | Country of origin | Methods | Intended for | Measuring ABPI advised. | Level of evidence | Barriers to accurate ABPI reading | Level of evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AWMA and NZWCS8 | 2011 | AUS/NZ |

Search: >3 databases, trial registries + reference lists. Search updated. SRs, RCTs, cohort, and CCS eligible. Included studies appraised using SIGN critical appraisal tool. |

Medical/surgical, GPs, allied, nurse practitioners, nurses, pharmacists, rural and indigenous health workers and consumers. | Yes, with Doppler Frequency not reported | CBRa | Untrained personnel, arterial calcification, severe oedema, lymphoedema, painful or extensive ulceration | CBRa |

| DGP23 | 2009 | GER |

SR methodology. Search: Explicit strategy, reference lists + hand searching RCTs eligible Selected articles evaluated with standardised checklist. |

Patients, phlebotomists, dermatologists, vascular surgeons, angiologists | Not reported | ‐ | Not reported | ‐ |

| DGfW20 | 2012 | GER |

Search: >5 databases. Explicit search strategy. Selected papers evaluated with standardised checklist. Evidence synthesised according to GRADE guidelines. |

Patients, GPs, physicians, nursing and other wound care specialists (in/out patient), podiatrists, PTs, insurers, the public | Not reported | ‐ | Not reported | ‐ |

| NHG21 | 2014 | NL | Update. Methodology not reported. | Dutch GPs |

Yes, with Doppler (plus referral to a PAD guideline24 |

Not reported | Not reported | ‐ |

| EDF10 | 2016 | SUI |

Search: Three databases searched, pre‐1995 search results + requested reference list. Selected articles appraised and graded. |

Dermatologists or other specialists | Yes, with hand‐held Doppler Frequency not reported | Level 2c level 3d | Persons with diabetes (medial sclerosis of arteries) | Level 3d |

| HAS25 | 2007 | FRA |

Systematic searches of French and English medical and scientific databases, specific databases, websites, grey lit., legislative and regulatory texts. CPGs, consensus conferences, medical decision aid articles, SRs, MA, and other assessments eligible. Guidelines graded according to quality of their evidence base. |

GPs, dermatologists, internal and physical medicine and vascular specialists, gerontologists, radiologists, nurses PTs, home help, and nursing auxiliaries. |

Yes, with continuous‐wave Doppler probe (plus referral to a Doppler technical report.26 Frequency not reported |

Grade Bj, Ck, and professional agreementl | Main limitation in interpreting ABPI values is medial calcification of arteries in elderly patients or patients with diabetes leading to risk of underestimating or failing to recognise PAOD. ABPI should be interpreted in light of physical findings, particularly palpation of pulses. | ‐ |

| ICP27 | 2005 | ITA |

Search: ≥2 databases. Particular consideration given to consensus statements prioritising MA and RCTs |

GPs | Not reported | ‐ | Not reported | ‐ |

| SIGN9 | 2010 | SCT |

Search: >3 databases + material identified by development group members. Quantitative and qualitative material eligible. Included articled appraised with SIGN checklist |

Patients, GPs, nursing, specialist nursing (dermatology, wounds, tissue viability, and rheumatology), dermatologists, vascular and plastic surgeons, pharmacists, podiatrists, and PTs. | Yes, with Doppler Frequency not reported. | Df, 2 + g | Calcified vessels (persons with diabetes or advanced chronic renal failure) may give misleadingly high results. Values >1.5 cannot be used to guide clinical decisions. | Level 4h |

| Sinha, S. & Sreedharan, S.28 | 2014 | AUS | A2B2C2D approach + TIME concept (necrotic tissue, infection, maceration, edge) of wound bed preparation. A short, evidence‐based practical guide. | GPs, practice nurses, physicians + scientists |

Yes, with Doppler in conjunction with combined clinical features. Frequency not reported |

Not reported | ABPI ≥1.2 may be because of a calcified artery. | ‐ |

| SIF and SICVE29 | 2016 | ITA |

GRADE methodology for leg ulcer section development. Search: ≥2 databases. Guideline, consensus conference + clinical evidence, informed opinions (new topics unsupported by evidence) eligible. Italian, English and international articles eligible. Included articles (mainly RCTs) evaluated for strength of evidence. |

Not reported | Yes, with Doppler Frequency not reported | 1Be | Not reported | ‐ |

| SVS and AVF30 | 2014 | USA |

De novo (SR & MA) development of surgery/endovascular and compression section recommendations. SRs with a priori protocols conducted (independent researchers). RCTs, CCTs, cohort, retrospective large observational CS eligible |

Specialists in vascular diseases and wounds. | Yes, with Doppler Frequency not reported | Level 1Be | Persons with diabetes, renal insufficiency, or other diseases that cause arterial calcification leading to false elevation of ankle pressure and ABPI. | Level 1Be |

| WHS23 | 2015 | USA |

Search: >3 databases, previous guidelines, MA, relevant reviews, reference lists + Medicare/CMS consensus of usual treatment of chronic wounds. SA, MA, consensus statements, RCTs, reviews, CS, retrospective series review, in vivo, protocols, pathological series reviews, evidence not specific to VLU eligible. Three‐level grading system that takes in vivo studies into account. Search updated. |

Not reported |

Yes, and/or with pedal pulse palpability Frequency not reported |

Level 1i | In elderly patients, patients with diabetes or an ABPI >1.2, a toe /brachial index of >0.6 or a trans‐cutaneous oxygen partial pressure of >40 mm Hg in the region of the ulcer may help to suggest an adequate arterial flow. | Level Ii |

| WOCN31 | 2012 | USA |

Search: >2 databases + reference lists. RCTs, prospective clinical trials, retrospective studies, SRs eligible. Level of evidence rating = 6 level taxonomy. |

Providers of direct care or wound care to patients with or at risk for LEVD. |

Yes, with Doppler Re‐check Q 12 weeks in patients with non‐healing ulcers |

Level Cb | Not reported | ‐ |

Abbreviations: ABPI, ankle‐brachial pressure index; AUS, Australia; AVF, American Venous Forum; AWMA, Australian Wound Management Association; CBR, consensus‐based recommendation; CCS, controlled clinical study; CCT, controlled clinical trial; CMS, The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid; CPG, clinical practice guideline; CS, case series; DGfW, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Wundheilung und Wundbehandlung e.V.; DGP, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Phlebologie; EDF, European Dermatology Forum; FRA, France; GER, Germany; GP, general practitioner; GRADE, Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations; HAS, Haute Autorité de Santé; ICP, Italian College of Phlebology; ITA, Italy; LEVD, lower extremity venous disease; MA, meta‐analysis; MS, meta‐synthesis; NHG, The Dutch College of General Practitioners; NL, The Netherlands; NZ, New Zealand; NZWCS, New Zealand Wound Care Society; PAD, peripheral arterial disease; PAOD, peripheral arterial occlusive disease; PT, physiotherapist; RCT, randomised controlled trial; SA, statistical analysis; SCT, Scotland; SICVE, Societa Italiano di Chirurgia Vascolare ed Endovascolare; SIF, Societa Italiano di Flebologia; SIGN, Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network; SR, systematic review; SUI, Switzerland; SVS, Society for Vascular Surgery; TIME, Necrotic Tissue, Infection, Maceration, Edge; VLU, venous leg ulcer; WOCN, Wound, Ostomy & Continence Nursing.

Consensus‐Based Recommendation, graded recommendation could not be made because of a lack of evidence.

Two relevant supporting case series (N ≥ 10), or expert opinion.

B: At least two independent studies conducted with a reference test, description of the investigated test and the population, but excluding characteristics that are mentioned further in A (A1: study into the effects of diagnostics on the clinical outcomes in a prospectively followed well‐defined patient group with a previously defined policy on the grounds of the to be investigated test results or a decision study into the effects the diagnostics on the clinical outcomes, whereby results of studies of A2 level are used as a basis and adequate consideration has been given to the mutual dependence of the diagnostic tests. A2: Study in light of a reference test with criteria defined a priori for the investigation test and for a reference test, with good description of the test and the studied clinical population; it must concern an adequately large series of consecutive patients and must make use of the pre‐defined cut‐off values, and the result of the test and the “gold standard” must have been assessed independently. In situations in which multiple diagnostic tests play a role, in principle, a mutual dependence and the analysis should be adjusted to this, for example, with logical regression).

One study of level A2 or B (see c) or a non‐comparative study.

Moderate‐quality evidence. Benefits clearly outweigh risks and burdens or vice versa. RCTs without important limitations (inconsistent results, methodological flaws, indirect, or imprecise) or exceptionally strong evidence from observational studies. Strong recommendations can apply to most patients in most circumstances without reservation.

Non‐analytic studies, for example, case reports, case series OR expert opinion OR extrapolated evidence from well‐conducted case‐control or cohort studies with a low risk of confounding or bias and a moderate probability that the relationship is causal.

Well‐conducted case‐control or cohort studies with a low risk of confounding or bias and a moderate probability that the relationship is causal.

Expert opinion.

Meta‐analysis of multiple RCTs or at least two RCTs supporting the intervention of the guideline. Another route would be multiple laboratory or animal experiments with at least two clinical series supporting the laboratory results.

Studies of an intermediate level of evidence (level of evidence 2), for example, RCTs with some bias, meta‐analyses based on questionable methodology, well‐conducted non‐randomised controlled trials, or cohort studies;

Studies of a lower level of evidence, for example, case‐control studies (level of evidence 3) or case series (level of evidence 4).

In the absence of reliable publications, the guidelines are based on professional agreement among members of the working group and peer reviewers.

Only 1 guideline27 did not specify an intended end user; the remaining 12 were typically written for specialists in dermatology, vascular disease, chronic wounds, rheumatology, gerontology and tissue viability, vascular and plastic surgeons, nurses, GPs, and allied health care providers such as podiatrists, nursing auxiliaries, physiotherapists, and home help and pharmacists.

3.3. Description of the systematic review methodology in CPGs

One guideline23 reported using a sequential or stepwise “A2B2D2C2D” + TIME (Necrotic Tissue, Infection, Maceration, Edge) concept of wound bed preparation as an approach to its development. The other 12 guidelines all used elements of systematic review methodology. One guideline searched >5 databases,20 four guidelines searched ≥3 databases,8, 13, 22, 34 three guidelines searched ≥2 databases,27, 28, 30 while the remainder29, 31, 32, 33 did not specify the number of databases searched. Guidelines from the Haute Autorité de Santé (HAS)29 was the only document that reported a grey literature search.

In cases where a systematic review methodology was reported, seven guidelines8, 22, 27, 29, 30, 31, 32 considered systematic reviews/meta‐analyses and/or randomised controlled trials to be eligible. Three8, 30, 32 accepted controlled clinical studies/prospective clinical trials, while one27 accepted cohort studies.

Three guidelines22, 28, 29 considered consensus statements/conferences as eligible with Italian College of Phlebology (ICP) guidelines,28 emphasising consensus that prioritised meta‐analyses and randomised controlled trials. Five guidelines22, 27, 29, 30, 32 accepted studies with a retrospective, case series, or other CPGs. The Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network (SIGN) guidelines13 accepted both quantitative and qualitative data. The Wound Healing Society (WHS) guidelines22 accepted data from in vivo studies (provided that they provided proof of concept and were corroborated by a clinical series) and evidence validating principles specific to other wound types that were considered to be applicable to VLU.

3.4. Evidence rating

Included articles were critically appraised using the SIGN critical appraisal tool by Australian and New Zealand (Australian Wound Management Association/New Zealand Wound Care Society [AWMA‐NZWCS])8 and SIGN13 guidelines. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Wundheilung und Wundbehandlung,20 Societa Italiano di Flebologia (SIF), and Societa Italiano di Chirurgia Vascolare ed Endovascolare (SIF/SICVE) guidelines 27 used the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations system. Wound, Ostomy & Continence Nursing (WOCN),30 European Dermatology Forum,34 Deutsche Gesellschaft für Phlebologie,24 and HAS guidelines29 used a non‐specified grading system, while WHS 22 used a grading system that took in vivo studies into account.

3.5. ABPI measurement recommendations

ABPI should be measured by a physician, GP, suitably trained staff, or appropriately trained staff with consistently maintained skills.13, 23, 30, 33 Of the 13 included CPGs, 320, 28, 31 did not explicitly recommend that ABPI be measured to rule out PAD. All others recommended that Doppler be used except WHS guidelines,22 which did not specify how ABPI should be measured. Dutch General Practitioner (The Dutch College of General Practitioners [NHG])33 and HAS29 guidelines refer the reader to a guideline for PAD26 and a technical report35 for ABPI methodology, respectively (Table 2).

Only one guideline explicitly recommended rechecking ABPI on a regular basis. WOCN guidelines advised that repeat ABPI assessments be carried out every 12 weeks in patients with non‐healing lower extremity ulcers.30 SIGN guidelines13 advise reassessment at 12 weeks if there is no progress and thereafter at 12‐week intervals. They also advise, among other considerations, ensuring that the aetiology of the ulcer has been confirmed (Table 2).

3.6. ABPI interpretation

Four guidelines8, 23, 29, 32 explicitly recommend or imply that ABPI measurement be interpreted in conjunction with combined clinical features, cardiovascular risk factors, and/or further investigation to confirm PAD. Levels of evidence supporting these recommendations, where reported, range from consensus opinion to moderate/intermediate quality (Table 2).

Six guidelines8, 13, 22, 23, 29, 34 all reported arterial calcification or diseases/conditions leading to arterial calcification as the primary reason for caution in interpreting ABPI scores. AWMA‐NZWCS guidelines8 also reported untrained personnel as a potential barrier to accuracy. Levels of evidence, where reported for this information, ranged from consensus/expert opinion to moderate/intermediate quality (Table 2).

3.7. ABPI and compression indication

Of the included CPGs, eight made recommendations in relation to indications/contraindications for compression therapy based on ABPI score (Tables 3 and 4). WOCN and ICP guidelines28, 30 recommend that reduced or low‐compression therapy can safely be initiated when the ABPI score is between 0.5 and 0.8 and 0.6 and 0.8, respectively. Five CPGs8, 13, 22, 27, 32 advise that compression therapy can safely be initiated when ABPI values are ≥0.6, ≥0.8, >0.8, >0.8 , or <1.2. According to HAS guidelines29, high‐level compression can be used safely in patients with an ABPI >0.8 or <1.3.

Table 3.

Summary of ABPI reporting in clinical practice guidelines: Compression indication

| Organisation/author | ABPI | Compression level for VLU management | Level of evidence or grade of recommendation | Compression level for VLU prevention | Level of evidence or grade of recommendation | Additional information, including reduced compression |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WOCN |

Not reported >0.5 to <0.8 |

High‐level compression Reduced‐level compression |

Level Aa Level Ce |

High‐level compression 40 to 50 mm Hgb |

Level Bd |

|

| SIF/SICVE |

≥0.6 ≥0.6 ≤ 0.8 |

Not reported Low‐pressure bandage |

Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

|

| SIGN | ≥0.8 | High‐level compression | 1++ level Grade Af | The strongest compression which patients can tolerate | Grade Af for the use of compression for VLU prevention | None |

| SVS and AVF |

≥0.8 ≥0.50 |

Standard compression Modified compression |

Grade 1, level Ag |

Compression was indicated The level was not reported |

Grade 2, level Bh |

|

| WHS | >0.8 | High‐level compression | 1i | The amount of compression that should be applied is controversial | 1i |

VLUs in patients with mild to moderate arterial insufficiency.

|

| EDF | Not reported | High‐level compression | 1j | High‐level compression | 2k |

|

| AWMA and NZWCS | >0.8 to <1.2 |

Compression was indicated. The level was not reported |

Level Bl |

Compression therapy 18 to 30 mm Hg |

Consensus‐based recommendationm |

|

| HAS |

>0.8 to <1.3 <0.8 > 1.3 |

High‐level compression 30 to 40 mm Hg Reduced level (below 30 mm Hg) |

Level Bn Professional agreement |

Highest tolerable Pressure that ensures compliance (>20 mm Hg at the Minimum, ideally 30 to 40 mm Hg) |

Level Bn |

Reduce pressure levels to below 30 mm Hg and prefer short‐stretch compression, which exerts low pressure while patients are resting. |

| ICP |

Not reported 0.6 to 0.8 |

Compression >40 mm Hg Inelastic material so as to exert low resting pressure |

Grade Ao Not reported |

Compression 30 to 40 mm Hg at the ankle or 40 to 50 mm Hg; elderly—20‐30 mm Hg at the ankle |

Grade Bp |

|

| Sinha and Sreedharan | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | N/A |

| DGfW | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | N/A |

| DGP | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

|

| NHG | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | N/A |

Abbreviations: ABI, ankle brachial index; ABPI, ankle‐brachial pressure index; AVF, American Venous Forum; AWMA, Australian Wound Management Association; CBR, consensus‐based recommendation; DGfW, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Wundheilung und Wundbehandlung e.V.; DGP, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Phlebology; EDF, European Dermatology Forum; HAS, Haute Autorite de Sante; ICP, Italian College of Phlebology; MECH, medical elastic compression hosiery; NHG, The Dutch College of General Practitioners; NZWCS, New Zealand Wound Care Society; PAD, peripheral arterial disease; RCT, randomised controlled trial; SICVE, Societa Italiano di Chirurgia Vascolare ed Endovascolare; SIF, Societa Italiana di Flebologia; SIGN, Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network; VLU, venous leg ulcer; WHS, Wound Healing Society; WOCN, Wound, Ostomy & Continence Society.

Recommendation based on two or more supporting RCTs of at least 10 humans with lower extremity venous ulcers (at Levels I or II), a meta‐analysis of RCTs, or a Cochrane Systematic Review of RCTs.

- Class A (light) 10 to 14 mm Hg (13‐19 hPa);

- Class I (mild) 15 to 21 mm Hg (20‐28 hPa);

- Class II (moderate) 23 to 32 mm Hg (31‐43 hPa);

- Class III (strong) 34 to 46 mm Hg (45‐61 hPa);

- Class IV (extra strong) >49 mm Hg (>65 hPa).

Recommendation based on one or more supporting controlled trials of at least 10 humans with lower extremity venous ulcers or two or more supporting non‐randomised trials of at least 10 humans with lower extremity venous ulcers (at Level III).

Recommendation based on two supporting case series of at least 10 humans with lower extremity venous ulcers or expert opinion.

At least one meta‐analysis, systematic review, or RCT rated as 1 ++ (High‐quality meta‐analyses, systematic reviews of RCTs, or RCTs with a very low risk of bias); a body of evidence consisting principally of studies rated as 1+ (well‐conducted meta‐analyses, systematic reviews, or RCTs with a low risk of bias) directly applicable to the target population and demonstrating overall consistency of results.

Strong recommendation, high‐quality evidence: Benefits clearly outweigh risk and burdens or vice versa, RCTs without important limitations or overwhelming evidence from observational studies; Strong recommendation, can apply to most patients in most circumstances without reservation.

Weak recommendation, moderate‐quality evidence: Benefits closely balanced with risks and burdens RCTs with important limitations (inconsistent results, methodologic flaws, indirect, or imprecise) or exceptionally strong evidence from observational studies; Weak recommendation, best action may differ depending on circumstances or patients' or societal values.

Meta‐analysis of multiple randomised controlled trials (RCTs) or at least two RCTs supporting the intervention of the guideline. Another route would be multiple laboratory or animal experiments with at least two clinical series supporting the laboratory results.

One systematic review A1 (Systematic reviews of at least several studies of A2 level, whereby the results of individual studies are consistent) of at least two independently conducted studies of levels A1 or A2 (Randomised comparative clinical study of good quality [randomised, double‐blind controlled trials] of adequate size and consistency).

At least two independently conducted studies of level B (Randomised clinical trials of moderate quality or inadequate size or other comparative study (not randomised, comparative cohort study, patient‐control study).

Good evidence — body of evidence can be trusted to guide practice in most situations.

Consensus evidence — a graded recommendation could not be made because of a lack of evidence from SRs or RCTs in populations with VLUs. The CBRs are supported by all members of the Expert Working Committee.

Studies of an intermediate level of evidence (level of evidence 2), for example, RCTs with some bias, meta‐analyses based on questionable methodology, well‐conducted non‐randomised controlled trials or cohort studies;

Recommendations based on large randomised clinical trials, or meta‐analyses, with no heterogeneity.

Recommendations based on randomised clinical trials, sometimes with small populations, and meta‐analyses including non‐randomised clinical trials, with some possible heterogeneity.

Table 4.

Summary of the ABPI reporting in clinical practice guidelines: Compression contraindication and referral recommendation

| Organisation/author | ABPI and compression contraindication | Level of evidence | ABPI and referral to specialist | Level of evidencea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WOCN | <0.5 | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| SIF/SICVE | ≤0.5 | Level C, grade 2a | Not reported | Not reported |

| SIGN | Not reported | Not reported | <0.8 | Level Db |

| SVS and AVF | ≤0.5 | Level C, grade 2c | ≤0.9 | Level B, grade 1d |

| WHS | <0.7 | 1e | Not reported | Not reported |

| EDF | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| AWMA and NZWCS | <0.8 or >1.2 | Not reported | <0.8 or >1.2 | Consensus‐based recommendationf |

| HAS | Not reported | Not reported | >0.85—superficial venous surgery with compression | Professional agreementg |

| ICP | <0.6 | Level Ah | Not reported | Not reported |

| Sinha and Sreedharan | Not reported | Not reported | ≤0.8—further investigation with duplex scan | Not reported |

| DGfW | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| DGP | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| NHG | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

Abbreviations: ABPI, ankle‐brachial pressure index; AVF, American Venous Forum; CBR, XXX; DGfW, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Wundheilung und Wundbehandlung e.V.; DGP, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Phlebology; EDF, European Dermatology Forum; HAS, Haute Autorite de Sante; ICP, Italian College of Phlebology; NHG, The Dutch College of General Practitioners; NZWCS, New Zealand Wound Care Society; RCT, randomised controlled trial; SIF/SICVE, Societa Italiana di Flebologia/Societa Italiano di Chirurgia Vascolare ed Endovascolare; SIGN, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network; SR, systematic review; SVS, Society for Vascular Surgery; VLU, venous leg ulcer; WHS, Wound Healing Society; WOCN, Wound, Ostomy & Continence Society.

Weak recommendation, low or very low quality of evidence, uncertainty in the evaluation of benefits, risks and factors that may or may weigh. Therapeutic alternatives can be considered.

Evidence level 3 or 4 or Extrapolated evidence from studies rated as 2+ (High‐quality systematic reviews of case‐control or cohort studies; High‐quality case‐control or cohort studies with a very low risk of confounding or bias and a high probability that the relationship is causal).

Weak recommendation, low quality or very‐low‐quality evidence. Uncertainty in the estimates of benefits and risk, and burdens; Risk, benefit, and burdens may be closely balanced. Observational studies or case. Series Very weak recommendations; Other alternatives may be reasonable.

Strong recommendation, moderate‐quality evidence Benefits clearly outweigh risk and burdens, or vice versa. RCTs with important limitations (inconsistent results, methodologic flaws, indirect, or imprecise) or exceptionally strong evidence from observational studies Strong recommendation, can apply to most patients in most circumstances without reservation.

Meta‐analysis of multiple RCTs or at least two RCTs supporting the intervention of the guideline. Another route would be multiple laboratory or animal experiments with at least two clinical series supporting the laboratory results.

Consensus evidence—a graded recommendation could not be made because of a lack of evidence from SRs or RCTs in populations with VLUs. The CBRs are supported by all members of the Expert Working Committee.

In the absence of reliable publications, the guidelines are based on professional agreement among members of the working group and peer reviewers.

Recommendations based on large randomised clinical trials, or meta‐analyses, with no heterogeneity.

3.8. ABPI and compression contraindication

Compression therapy is contraindicated in patients with an ABPI score <0.5,30 ≤0.5,27, 32 <0.6,28 <0.7,22 and <0.8 or > 1.28 (Table 4).

3.9. ABPI and precautions to compression therapy

Society for Vascular Surgery‐American Venous Forum (SVS‐AVF) guidelines32 recommend that compression therapy can be used but under close monitoring when ABPI scores >0.5. WOCN guidelines30 make a similar recommendation when the ABPI score is >0.5 and < 0.8. ICP guidelines28 advise close monitoring for patients on compression therapy with an ABPI score >0.6 and <0.8. SIGN guidelines13 recommend close observation when compression therapy is used in patients whose ABPI score <0.8, while AWMA‐NZWCS8 states that compression therapy should be closely monitored in patients whose ABPI <0.8 and >1.2.

3.10. ABPI and referral to specialist services

HAS guidelines29 recommend superficial venous surgery with compression when a patient has an ABPI score >0.85. Sinha23 suggests further investigation with duplex scan when ABPI scores reach 0.8 or less. Arrangements for specialist referral should be made when ABPI scores are <0.8 or >1.2 according to AWMA‐NZWCS,8 while SIGN13 and SVS‐AVF32 guidelines report that referral to a specialist be made when patient ABPI scores <0.8 and <0.9, respectively.

3.11. Compression recommendations for VLU prevention

Of the included 13 guidelines, 88, 13, 22, 28, 29, 30, 32, 34 discussed the use of compression therapy for prevention of the VLU recurrence; and only 5 guidelines8, 28, 29, 30, 34 indicated the level of compression recommended for prevention (Table 3). However, the provided suggestions regarding the level of compression were different. For example, HAS29 recommends the highest tolerable pressure that ensures compliance starting from 20 mm Hg at the minimum but, ideally, 30 to 40 mm Hg; AWMA‐NZWCS8—18 to 30 mm Hg pressure; and the Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society™ (WOCN)30 – 40 to 50 mm Hg.

4. DISCUSSION

CPGs are designed to improve quality of care, reduce practice variation, and support clinician decision‐making process to optimise patient healing outcomes taking into consideration clinical assessment and patient preferences. Our review shows there is a lack of consensus across 13 VLU CPGs and a lack of clear guidance in relation to the specific ABPI range of compression therapy that can be safely applied. The lack of consensus may be an additional barrier to the barriers (eg, lack of time, cost, equipment availability) reported by health professionals.36

Based on our review, we can say with a high level of confidence that compression therapy is contraindicated if the ABPI is ≤0.5. In total, six guidelines state it is contraindicated at an ABPI ranging from <0.5 to <0.8,8, 22, 27, 28, 30, 32 with four of these advocating for reduced compression,27, 28, 30, 32 while one27 states it can be applied with an ABPI of ≥0.6. One guideline8 states it is contraindicated at an ABPI >1.2. An area of uncertainty and disagreement exists in relation to an ABPI between 0.6 and 0.8, with some guidelines advocating that compression is contraindicated and others that there should be reduced compression. This has implications in clinical practice, including when it is safe to apply compression and when to refer for specialist review. In addition, it also has implications for inclusion and exclusion criteria for VLU clinical studies. It is not unusual to have an ABPI of ≥0.75 as an inclusion in some studies,37 thus having further implications for generalisability.

Only one CPG30 made reference to reassessment using ABPI, and in this case, it was after 12 weeks of therapy. Anecdotal evidence suggests that the best practice is to reassess the ABPI every 3 months, especially in those with slow‐healing ulcers.

We recommended that individuals presenting with VLU be assessed for ABPI by trained clinicians. The quality of the initial assessment is important. The challenge for the non‐specialised clinicians working in community settings is that CPGs do little to assist in the decision‐making process. Although training is important, if clinicians do not have ongoing opportunities to maintain knowledge, skills, and practice, they may not develop sufficient expertise for safe practice. For example, if a clinician has been trained but only gets the opportunity to do an ABPI once a month or less frequently, it may be challenging to maintain ABPI measurement skills. For clinicians practicing in isolation and possibly without the equipment to measure ABPI, they may not know that their practice is suboptimal. The included CPGs have conflicting statements to ABPI, which increases clinical practice variability and a potential consequence that patients may or may not receive compression. In addition, the CPGs are suboptimal in advising attending clinicians when to refer patients for specialist assessment.

Specialist clinicians, including vascular physicians and surgeons and tissue viability nurses, often have access to a wider range of equipment when compared with non‐specialised community clinicians. Based on their in‐depth assessment and expert knowledge, they may often recommend full compression at ABPIs less than 0.8. However, these individuals are rarely the target group for these guidelines. In our review, the CPG target groups were largely non‐specialised clinicians. Thus, the question remains as to when compression, either reduced or full, should be initiated with an ABPI 0.6 to 0.8. The ABPI score range of 0.6 to 0.8 is very much a grey area, and more clarification is needed here. There is no agreement or clarity on the optimum level of compression, which is a gap that needs to be addressed.

Five CPGs27, 28, 29, 30, 32 made recommendations regarding reduced compression in the context of ABPI scores. Reduced or modified compression was recommended when the ABPI >0.5 to <0.8,30 ≥0.5,32 between 0.6 and 0.8,27, 28 and <0.8 or >1.3.29 No other guideline differentiate between standard compression and reduced compression, although WHS guidelines did state that the degree of compression must be modified when mixed arterial/venous disease is confirmed during the diagnostic work‐up,22 and AWMA‐NZWCS guidelines advised that potential modifications in the high‐risk patient may include a reduction in level of compression (AWMA 2011).

Two key points emerge from this review1: there is a lack of guidance on the use of compression therapy in patients with an ABPI score of 0.6 to 0.8, and2 the lack of certainty and agreement across CPGs is a barrier to the uptake of guidelines, which has not been explicitly stated in other papers.

4.1. Implications for development and revisions of the VLU CPGs

We know high‐quality CPGs have the potential to improve health care decisions, reduce harm, and enhance health care quality and outcomes.38, 39, 40 However, the inconsistency in the levels of evidence and the grades of recommendation makes it difficult to compare them across various guidelines and reduces the quality of recommendations.41 There is an opportunity for future CPGs in VLU management to reduce uncertainty through the development of consensus based on evidence and using the Reporting Tool for Practice Guidelines in Health Care (RIGHT framework http://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/right-statement/). There is an urgent need to strengthen the guideline recommendations to optimise evidence‐based care.

4.2. Implications for clinical practice

Compression is indicated and could be safely applied for VLU management if ABPI is 0.8 to 1.2 mm Hg.

Compression is not recommended if ABPI is >1.2 mm Hg.

Compression is absolutely contraindicated if ABPI is <0.5 mm Hg. Specialist referral is recommended, including vascular surgeon, tissue viability specialist, and dermatologist.

Referral to a specialist is recommended if ABPI is <0.8 or >1.2 mm Hg, which is indicative of PAD and suggestive of possible arterial calcification.

If ABPI is >1.3 mm Hg, TBPI could be calculated, which is considered more accurate for identifying arterial perfusion in the feet and toes of patients with diabetes and renal disease.

If ABPI is >0.6 to <0.8, graduated compression therapy could be applied in the absence of arterial disease or diabetes mellitus. Aim for ≤ 30 mmHg (elastic) or high stiffness system (inelastic). Compression should be applied by a trained health professional according to manufacturer's instructions.

For patients with the ABPI score of between 0.6 and 0.8, ABPI reassessment every 12 weeks is recommended.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

All persons designated as authors qualify for authorship. Each author has participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for the content.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We extend our thanks to Prof. Dr. Anke Simon, RN, MBA, PhD and Massimo Rivolo, RGN, BSc (Hons), MSc Wound Care for their assistance with screening and extraction of data from German‐ and Italian‐language CPGs. Prof. Carolina Weller is funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council Translating Research into Clinical Practice Fellowship APP1132444.

Weller CD, Team V, Ivory JD, Crawford K, Gethin G. ABPI reporting and compression recommendations in global clinical practice guidelines on venous leg ulcer management: A scoping review. Int Wound J. 2019;16:406–419. 10.1111/iwj.13048

REFERENCES

- 1. Franks PJ, Barker J, Collier M, et al. Management of patients with venous leg ulcers: challenges and current best practice. J Wound Care. 2016;25(Suppl 6):S1‐s67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nelson EA, Adderley U. Venous leg ulcers. BMJ Clin Evid. 2016;2016:1902. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Weller CD, Evans S. Venous leg ulcer management in general practice. Practice nurses and evidence based guidelines. Aust Fam Physician. 2012;41(5):331‐337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Weller CD, Ademi Z, Makarounas‐Kirchmann K, Stoelwinder J. Economic evaluation of compression therapy in venous leg ulcer randomised controlled trials: a systematic review. Wound Pract Res. 2012;20(1):21. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Guest JF, Fuller GW, Vowden P. Venous leg ulcer management in clinical practice in the UK: costs and outcomes. Int Wound J. 2018;15(1):29‐37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Guest J, Vowden K, Vowden P. The health economic burden that acute and chronic wounds impose on an average clinical commissioning group/health board in the UK. J Wound Care. 2017;26(6):292‐303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. O'Meara S, Cullum N, Nelson EA, Dumville JC. Compression for venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;11:CD000265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Australian Wound Management Association, New Zealand Wound Care Society . Australian and New Zealand Clinical Practice Guidelines for Prevention and Management of Venous Leg Ulcers. Osborne Park, Australia: Cambridge Publishing; 2011.

- 9. Wounds Australia . Standards for Wound Prevention and Management. 3rd ed. Osborne Park, Australia: Cambridge Media; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kelechi TJ, Johnson JJ, Yates S. Chronic venous disease and venous leg ulcers: an evidence‐based update. J Vasc Surg. 2015;33(2):36‐46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chesbro SB, Asongwed ET, Brown J, John EB. Reliability of Doppler and stethoscope methods of determining systolic blood pressures: considerations for calculating an ankle‐brachial index. J Natl Med Assoc. 2011;103(9):863‐869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vowden P, Vowden K. Doppler Assessment and ABPI: Interpretation in the Management of Leg Ulceration. World Wide Wounds. 2001. http://www.worldwidewounds.com/2001/march/Vowden/Doppler‐assessment‐and‐ABPI.html. Accessed November 24, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Scottish Intercollegiate Network (SIGN) . Management of chronic venous leg ulcers: A national clinical guideline Edinburgh. NHS Quality Improvement Scotland; 2010. http://www.sign.ac.uk/assets/sign120.pdf Accessed November 23, 2018.

- 14. Caruana MF, Bradbury AW, Adam DJ. The validity, reliability, reproducibility and extended utility of ankle to brachial pressure index in current vascular surgical practice. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2005;29(5):443‐451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. WOCN Wound Committee . Ankle brachial index: quick reference guide for clinicians. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2012;39(2S):S21‐S29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Team V, Canaway R, Manderson L. Integration of complementary and alternative medicine information and advice in chronic disease management guidelines. Aust J Prim Health. 2011;17(2):142‐149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Andriessen A, Apelqvist J, Mosti G, Partsch H, Gonska C, Abel M. Compression therapy for venous leg ulcers: risk factors for adverse events and complications, contraindications ‐ a review of present guidelines. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(9):1562‐1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Neuendorf KA. The Content Analysis Guidebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gallenkemper GB, Gerlach H, Junger M. Guidelines in diagnosis and therapy of chronic venous insufficiency. Phlebologie. 2000;29(4):102‐105. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bartkowski R, et al. Lokal Therapie Chronischer Wunden Bei Patienten Mit den Risiken Periphere Arterielle Verschlusskrankheit, Diabetes Mellitusm Chronische Cenose Insuffizienz 2012; 2018. https://www.deutsche‐diabetes‐gesellschaft.de/fileadmin/Redakteur/Leitlinien/Evidenzbasierte_Leitlinien/091‐001l_S3_Lokaltherapie_chronischer_Wunden_2012‐06.pdf. Accessed November 23, 2018.

- 21. Tang JC, Marston WA, Kirsner RS. Wound Healing Society (WHS) venous ulcer treatment guidelines: what's new in five years? Wound Repair Regen. 2012;20(5):619‐637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Marston W, Tang J, Kirsner RS, Ennis W. Wound Healing Society 2015 update on guidelines for venous ulcers. Wound Repair Regen. 2016;24(1):136‐144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sinha S, Sreedharan S. Management of venous leg ulcers in general practice ‐ a practical guideline. Aust Fam Physician. 2014;43(9):594‐598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wilm S, Wollny A, Rieger MA. Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Phlebologie: DGP und DeGAM gemeinsam erstellte Kurzversion zum Ulcuc cruris venosum 2010; 2017. www.degam-leitlinien.de. Accessed November 23, 2018.

- 25. Neumann HAM, Cornu‐Thenard A, Juenger M, et al. Evidence‐based (S3) guidelines for diagnostics and treatment of venous leg ulcers. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30(11):1843‐1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Van Kaiser H, Stoffers HE, Van der Laan JR. NHG‐standaard perifeer arterieel vaatlijden. In: Bartelink MEL, Elsman BHP, Oostindjer A, Stoffers HEJH, Wiersma Tj, Geraets JJXR, eds. NHG‐Standaarden voor de huisarts. Deel 1. Maarssen, the Netherlands: Elsevier/Bunge; 1999:252‐264. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ebner H, Stillo F, Lanza G, et al. Linee guida flebo‐linfologiche SIF‐SICVE 2016 della Società Italiana di Flebologia e della Società Italiana di Chirurgia Vascolare ed Endovascolare. Minerva Cardioangiol. 2016;64(4):1‐80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Agus GB, Allegra C, Antignani PL, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and therapy of the vein and lymphatic disorders. Int Angiol. 2005;24(2):107‐168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Haute Autorité de Santé . Management of leg ulcers of predominantly venous origin (dressing excluded). J Mal Vasc. 2007;32(2):100‐111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kelechi TJ, Johnson JJ. Guideline for the management of wounds in patients with lower‐extremity venous disease: an executive summary. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2012;39(6):598‐606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Junger M, Partsch H, Kahle B. Leitlinien Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Phlebologie: Phlebolischer Kompressionsverband (PKV). Phlebologie. 2009;38:168‐171. [Google Scholar]

- 32. O'Donnell TF Jr, Passman MA. Clinical practice guidelines of the Society for Vascular Surgery (SVS) and the American Venous Forum (AVF)‐Management of venous leg ulcers. Introduction. J Vasc Surg. 2014;60(2 Suppl):1s‐2s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schweitzer BPM, Doorenbosch J, Glotzbach R, et al. NHG Practice Guideline 'Venous leg ulcer'. 2014. https://pdfsecret.com/download/nhg‐practice‐guideline‐venous‐leg‐ulcer_5a1df6bbd64ab217dbbfeed8_pdf. Accessed November 23, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Neumann HA, Cornu‐Thenard A, Junger M, et al. Evidence‐based (S3) guidelines for diagnostics and treatment of venous leg ulcers. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30(11):1843‐1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Agenee Nationale d'Accréditation et d'Evaluation en Santé (ANAES) . L'échographie‐Doppler dans l'artériopathie oblitérante des membres inférieurs. Agenee Nationale d'Accréditation et d'Evaluation en Santé (ANAES); 2002. https://docplayer.fr/8042781‐Echographie‐doppler‐dans‐l‐arteriopathie‐obliterante‐des‐membres‐inferieurs.html. Accessed November 23, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ding TG. The Use of the Ankle Brachial Pressure Index (ABPI) in General Practice: A Mixed Methods Study. Dunedin, New Zealand: University of Otago; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Alvarez O, Phillips T, Menzoian J, Patel M, Andriessen A. An RCT to compare a bio‐cellulose wound dressing with a non‐adherent dressing in VLUs. J Wound Care. 2012;21(9):448‐453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Grimshaw JM, Russell IT. Effect of clinical guidelines on medical practice: a systematic review of rigorous evaluations. Lancet. 1993;342(8883):1317‐1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Moher D, Schulz KF, Simera I, Altman DG. Guidance for developers of health research reporting guidelines. PLoS Med. 2010;7(2):e1000217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Eccles M, Grimshaw J, Foy R. Disseminating and Implementing Evidence‐ Based Practice. In: Van Zwanenberg T, Harrison J, eds. Clinical Governance in Primary Care. London: CRC Press; 2018:75‐88. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, et al. GRADE Working GroupGRADE guidelines: 7. Rating the quality of evidence—inconsistency. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(12):1294‐1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]