Abstract

Diabetic foot ulceration (DFU) is a common and debilitating complication of diabetes that is preventable through active engagement in appropriate foot‐related behaviours, yet many individuals with diabetes do not adhere to foot care recommendations. The aim of this paper was to synthesise the findings of qualitative papers exploring diabetic people's perceptions and experiences of DFU in order to identify how they could be better supported to prevent ulceration or manage its impact. Five databases (MEDLINE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, EMBASE, Web of Science) were searched in May 2016 to identify eligible articles. Findings were synthesised using a meta‐ethnographic approach. Forty‐two articles were eligible for inclusion. Synthesis resulted in the development of five overarching themes: personal understandings of diabetic foot ulceration; preventing diabetic foot ulceration: knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours; views on health care experiences; development of diabetic foot ulceration and actions taken; and wide‐ranging impacts of diabetic foot ulceration. The findings highlight various barriers and facilitators of foot care experienced by people with diabetes and demonstrate the significant consequences of ulcers for their physical, social, and psychological well‐being. The insights provided could inform the development of interventions to promote foot care effectively and provide appropriate support to those living with ulceration.

Keywords: diabetic foot ulcer, foot care, patient experience, qualitative

1. INTRODUCTION

Diabetic foot ulceration (DFU) is among the most common and debilitating complications of diabetes, with a lifetime incidence of up to 25% in people with this condition.1 DFU represents a major health problem in this population because of its deleterious impact on physical and psychosocial functioning2 and increased risks of DFU recurrence,3 amputation,1 and mortality.4 Treatment is expensive and challenging, often involving prolonged hospitalisation and complex medical procedures. At least one‐third of direct costs generated by the treatment of diabetes and its complications in the United States is linked to DFU.5 The personal, societal, and economic costs of DFU, coupled with the rapidly increasing prevalence of diabetes worldwide,6 highlights the importance of developing effective prevention strategies and supports.

DFU is multifactorial in causation, usually resulting from interactions between biological risk factors (eg, peripheral neuropathy) and foot‐related behaviours (eg, wearing ill‐fitting shoes). It is estimated that at least 75% of all cases could be avoided through high‐quality preventive care.7 The patient's active engagement in foot care is a cornerstone of successful prevention.8, 9 Key behaviours that reduce the risk of developing DFU include daily inspection of feet and immediate reporting of irregularities to a health professional, avoidance of behaviours that place the foot at risk (eg, walking barefoot), consistent use of appropriate footwear, and attendance of annual foot screening.9, 10 However, many individuals with diabetes do not practice these behaviours.8, 11, 12 For example, almost two‐thirds check their feet rarely if at all,8 and few adhere to footwear recommendations.13, 14

The importance of the patient's perspective in successfully promoting engagement in foot care has been widely noted.2, 8, 15 Although national and international guidelines on the management of the diabetic foot strongly emphasise educating patients in appropriate foot self‐care,8, 9 the efficacy of existing interventions is limited; this has been attributed to their inattention to the psychosocial processes underlying foot‐related behaviours.2 Exploring patients' views and experiences of DFU may help to further our understanding of the factors that contribute to their engagement in foot care, identify targets for interventions that will effectively promote these behaviours, and ensure that recommendations for practice fit with their needs and personal interpretations of this condition.

A meta‐synthesis involves drawing together the findings of qualitative studies in order to build a more in‐depth understanding of a specific phenomenon and is being used increasingly to inform health‐related policy and practice.16 The aim of the present review is to conduct a meta‐synthesis of qualitative studies exploring the perceptions and experiences of individuals with diabetes regarding DFU. It is anticipated that our findings will offer useful insights on how individuals with diabetes could be better supported to prevent, or manage the impact of, DFU.

2. METHODS

2.1. Search strategy

MEDLINE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, Embase, and Web of Science databases were searched from inception to 11 May 2016 (see Appendix for a sample search strategy). A comprehensive list of qualitative methodology search terms was included to maximise the identification of relevant articles.17 Reference lists of eligible papers were hand‐searched for additional material. Two authors (L.C. and C.M.) screened titles and abstracts for relevance and independently reviewed the full texts of potentially eligible papers. Any disagreements were discussed and brought to a third author (P.G.) if consensus could not be reached.

2.2. Selection criteria

Papers were included if they (a) included a sample of adults (ie, aged 18 years+) with diabetes and explored their perceptions and/or experiences of DFU, (b) used qualitative methods of data collection and analysis, (c) were written in English, and (d) were published in a peer‐reviewed journal. Papers were excluded if (a) they included individuals without diabetes in their samples and did not report findings for participants with diabetes separately or (b) their qualitative findings lacked sufficient detail to contribute meaningfully to the synthesis (ie, no themes reported).

2.3. Quality assessment

The quality of included papers was assessed independently by two authors (L.C. and C.M./P.G.) using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) qualitative research checklist.18 CASP considers the rigour and credibility of evidence in eight areas: research design, recruitment, data collection, reflexivity, ethical issues, data analysis, findings, and value of the research. Reviewers used a three‐point rating system19 to assign scores based on whether the paper being assessed was considered to provide a weak (a), moderate (b), or strong (c) explanation of each area. Any differences between scores were resolved through discussion and reference to a third reviewer (C.M./P.G.) if required. Scores were summed for each paper, giving a possible score of 8 to 24. Papers were not excluded on the basis of their scores; reviews were conducted to aid readers' critical consideration of their credibility.

2.4. Data synthesis

A meta‐ethnographic approach,20, 21 which has been applied extensively in health care research on patient experiences of illness and care,16 was used to synthesise data. The Enhancing Transparency of Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research (ENTREQ) statement22 was followed. Eligible papers were read and re‐read by L.C. and C.M.; their details were recorded by C.M. using a data extraction form. A table of first‐ and second‐order constructs relevant to the aim of the meta‐synthesis was compiled for each paper by L.C. First‐order constructs are study participants' interpretations of their experience (ie, direct quotations); second‐order constructs are study authors' interpretations of participants' accounts. Using these tables, L.C. grouped conceptually similar constructs from different papers together to identify key concepts (ie, common and recurring themes). A grid of key concepts was then produced and used to develop third‐order constructs (ie, the views and interpretations of the synthesis team, expressed in terms of higher‐order themes and sub‐themes). L.C. led the synthesis; third‐order constructs were confirmed independently by C.M. and P.G.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Study selection

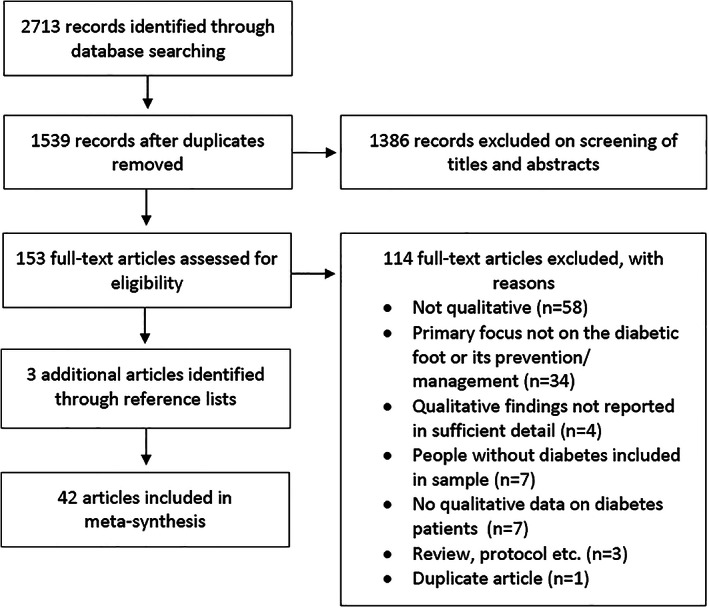

The systematic search yielded 1539 results excluding duplicates, of which 1386 were excluded at title/abstract. Full texts of the remaining 153 articles were obtained; 114 were excluded upon reading. Three additional papers were identified from the reference lists of included papers. Overall, 42 articles23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64 reporting the findings of 35 qualitative studies were selected for inclusion (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of article selection process

3.2. Study characteristics

The characteristics of included papers are summarised in Table 1. The majority were based on research conducted in the United Kingdom (n = 18); the remaining papers originated from Sweden (n = 4), the United States (n = 3), Australia (n = 2), Brazil (n = 2), Jordan (n = 2), Norway (n = 2), Barbados (n = 1), Bermuda (n = 1), Canada (n = 1), France (n = 1), Iran (n = 1), Ireland (n = 1), South Africa (n = 1), and Uganda (n = 1); one included participants from Germany, Italy, and the United Kingdom. Sample sizes were reported in all but one paper26 and ranged from 3 to 67. DFU status varied across studies, where reported. In 32 papers, all participants had previous or current diabetes‐related foot complications. In five papers, some (n = 4) or all (n = 1) participants were described as having no history of ulceration; five papers did not specify participants' foot health status. Thirty‐three papers used interviews as their primary method of qualitative data collection, six used focus groups, and three incorporated both methods.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included papers

| First author (year of publication) | Country | Recruitment setting | Aim | Sample size | Gender | Age | Disease status | Method of data collection | CASP score (/24) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abu‐Qamar (2012)23 | Jordan | 6 hospitals, one health care centre | To elaborate patients' views of diabetic foot care within the Jordanian health care system | 7 | 4 males, 3 females | 52–69 y | Diabetes (duration of up to 29 y); foot burn injury | Unstructured face‐to‐face interviews | 14 |

| Abu‐Qamar (2011)24 | Jordan | 6 hospitals, one healthcare centre | To illuminate the lived experience of diabetic patients who have sustained foot burn injuries | 7 | 4 males, 3 females | 52–69 y | Diabetes (duration of up to 29 y); foot burn injury | Unstructured face‐to‐face interviews | 18 |

| Aliasgharpour (2012)25 | Iran | Large urban hospital | To clarify the care process for Iranian diabetic patients with diabetic foot ulcer condition | 11 | Not reported | Not reported | Diabetes; diabetic foot ulcer condition | Semi‐structured interviews | 15 |

| Anders (2010)26 | Germany, Italy, United Kingdom | Recruited from data held by market research companies | To provide insight into the perceptions, motivations, and barriers to successful foot care among people with diabetes | Not reported | Not reported | 40–65 y |

Type 1 or type 2 diabetes One group of people with a history of diabetic foot ulceration One group of men at low risk of diabetes‐related foot problems One group of women at low risk of diabetes‐related foot problems |

Focus groups | 12 |

| Ashford (2000)27 | United Kingdom | Hospital outpatient clinic for people with diabetic foot problems | To address quality‐of‐life issues in patients with diabetic foot ulcers | 21 | 15 males, 6 females | 49–75 y | Type 1 (n = 12) or type 2 (n = 9) diabetes (duration of 6 mo to 30 y); diabetic foot ulceration | Semi‐structured face‐to‐face interviews | 14 |

| Beattie (2014)28 | United Kingdom | Hospital podiatry clinics | To examine the emotional and behavioural consequences of living with heightened risk of re‐ulceration | 15 | 7 males, 8 females | 26–73 y | Type 1 (n = 7) or type 2 (n = 8) diabetes; history of diabetic foot ulcers but ulcer‐free at present | Semi‐structured face‐to‐face interviews | 21 |

| Bradbury (2011)29 | United Kingdom | Specialist diabetic foot clinic | To explore the effect of DFU pain on quality of life from the patient's perspective | 3 | 2 males, 1 females | 71–86 y | Type 2 diabetes (duration of 10‐30 y); active diabetic foot ulceration | Semi‐structured face‐to‐face interviews | 20 |

| Brod (1998)30 | United Kingdom | Not reported | To examine the impact of lower‐extremity ulcers on the quality of life of patients with diabetes and their caregivers | 14 | 8 males, 6 females | 19–77 y | Diabetes (duration of 5–51 y, mean = 20 y); active lower‐extremity ulceration | Focus groups | 12 |

| Burnside (2007)31 | United Kingdom | GP surgeries | To explore patient experiences and preferences for the delivery of educational material regarding foot care | 18 | 12 males, 6 females | Mean age = 71 y | Diabetes; loss of peripheral sensation; no history of DFU (n = 10) or current/previous DFU (n = 8) | Semi‐structured face‐to‐face interviews | 14 |

| Burton (2007)32 | United Kingdom | Orthotic vascular clinic | To explore the experiences of adults with diabetes regarding the prescription and wearing of orthotic devices to better understand why some patients chose not to wear them | 8 | 6 males, 2 females | 41–76 y | Type 1 (n = 5) or type 2 (n = 3) diabetes; prescribed a patellar‐tendon‐bearing orthosis; DFU status not specified | Semi‐structured face‐to‐face interviews | 20 |

| Chadwick (2002)33 | United Kingdom | Not reported | To explore the health knowledge, beliefs, behaviours, and decisions of people with type 2 diabetes who ulcerate for the first time | 8 | Not reported | Not reported | Type 2 diabetes; first‐time diabetic foot ulcer | Semi‐structured face‐to‐face interviews | 18 |

| Chithambo (2015)34 | United Kingdom | Diabetes foot clinic | To explore patients' reasons for delay in seeking help with diabetes‐related foot problems | 6 | 4 males, 2 females | 49–69 y | Type 1 (n = 1) or type 2 (n = 5) diabetes (duration of 8 mo‐49 y); presenting with gangrenous ulcers and/or requiring partial/full lower limb amputation | One‐to‐one semi‐structured interviews | 21 |

| Coelho (2009)35 | Brazil | Referral service for chronic diseases | To understand the social representations of the diabetic foot for people with type 2 diabetes | 10 | 4 males, 6 females | 53–77 y | Type 2 diabetes (duration of 7–41 y); DFU status not specified | Focus groups; semi‐structured interviews | 13 |

| de Vera (2003)36 | United States | Pascua Yaqui reservation | To describe the perspectives of Yaqui native Americans with diabetes regarding biomedical and traditional methods for healing foot ulcers | 4 | 1 male, 3 females | 58–76 y |

Non‐insulin‐dependent diabetes; healed (n = 3) or active (n = 1) diabetic foot ulceration |

Participant observation, semi‐structured interviews, field notes | 21 |

| Delea (2015)37 | Ireland | Prosthetic rehabilitation outpatient unit |

To explore the attitudes and experiences of foot care services in Ireland among people with diabetes and active foot disease or lower limb amputations. Explore what service users believe are the positive and negative aspects of the care they have received and the ways in which services could be improve |

10 | 10 males | 40–72 y | Type 1 (n = 4) and type 2 (n = 6) diabetes; active diabetic foot disease in both feet (n = 1), transtibial amputation as a result of diabetes (n = 6), transfemoral amputation as a result of diabetes (n = 3) | Semi‐structured interviews | 20 |

| Foster (2014)38 | United States | Suburban community | To explore the lived experience of patients who have had an amputation resulting from a diabetic foot ulcer | 15 | 10 males, 5 females | <60 y (n = 2), 60–64 y (n = 3), 65–69 y (n = 6), 70–74 y (n = 1), 75–79 y (n = 2), 80–84 y (n = 1) | Diabetes; amputation as a result of diabetic foot ulcer [toes (n = 9); transmetatarsal (n = 5); below‐knee (n = 5); above‐knee (n = 5)] | Semi‐structured face‐to‐face interviews | 18 |

| Fox (2005)39 | Canada | Wound management clinic | To explore the experiences of people with a diabetic foot ulcer in order to acquire a better understanding of their needs and to develop recommendations for improving support | 10 | 6 males, 4 females | 40–70 y | Diabetes (duration of 5–25 y); diabetic foot ulceration (duration of 8 mo‐18 y) | Semi‐structured face‐to‐face interviews | 13 |

| Gale (2008)40 | United Kingdom | Suburban primary care health Centre | To explore beliefs about diabetic foot complications and everyday foot self‐care practices among people with type 2 diabetes | 18 | 9 males, 9 females | Mean age = 64 y |

Type 2 diabetes (mean duration of 6.5 y); no history of diabetic foot ulceration |

Semi‐structured face‐to‐face interviews | 17 |

| Guell (2015)41 | Barbados | Two public polyclinics | To explore barriers to foot care from the perspectives of health care professionals and patients, with a view to informing further work to develop effective interventions | 9 | Not reported | Not reported | Diabetes; range of experiences with foot disease (from no known diabetic foot disease to amputations) | Semi‐structured face‐to‐face interviews | 18 |

| Hill (2015)42 | United Kingdom | Podiatry clinic |

To determine the patient Education approach that individuals with diabetes Mellitus were exposed to, as well as exploring patient perceptions and the impact of foot health |

20 | Not reported | >18 y | Type 1 or type 2 diabetes (for at least 18 mo) | Semi‐structured face‐to‐face interviews | 17 |

| Hjelm (2002)43 | Sweden | Specialised multidisciplinary diabetic foot clinic | To explore beliefs about health and illness in patients with diabetic foot ulcers investigated from a patient perspective | 39 |

23 males, 16 females (11 males, 12 females aged <65 y; 12 males, 6 females aged >65 y) |

23–83 y | Diabetes (duration of 5–55 y); current/previous diabetic foot ulcer | Focus groups | 17 |

| Hjelm (2002)44 | Sweden | Specialised multidisciplinary diabetic foot clinic | To ascertain patients’ evaluations of a specialised multidisciplinary diabetic foot clinic and its contribution to an improved coping capability to promote health in the patients receiving care | 39 |

23 males, 16 females (11 males, 12 females aged <65 y; 12 males, 6 females aged >65 y) |

23–83 y | Diabetes; (duration of 5–55 y); current/previous history of diabetic foot ulceration | Focus groups | 21 |

| Hjelm (2003)45 | Sweden | Two hospital‐based diabetes clinics | To explore beliefs about health and illness among foreign‐born and Swedish diabetic men with severe diabetic foot lesions that might affect their self‐reported self‐care practice and care‐seeking behaviour | 26 | 26 males [Swedish‐born (n = 11); foreign‐born (n = 15)] | 38–74 y | Diabetes (duration of 5–55 y); current/previous diabetic foot ulceration |

Focus groups (Swedish‐born participants); semi‐structured face‐to‐face interviews (foreign‐born participants) |

16 |

| Hjelm (2009)47 | Sweden | Diabetic foot clinic | To elucidate how diabetic patients with limb‐threatening foot lesions perceive and evaluate content and organisation of treatment in a multi‐place hyperbaric oxygen chamber | 19 | 13 males, 6 females | 44–83 y |

Diabetes (duration of 9–52 y); non‐healing longstanding diabetic foot ulcers; receiving hyperbaric oxygen chamber treatment |

Focus groups | 17 |

| Hjelm (2013)46 | Uganda | Surgical ward of a university hospital | To explore beliefs about health and illness among Ugandans with diabetic foot ulcers that might affect self‐care and care‐seeking behaviour | 14 | 4 males, 10 females | 40–79 y | Diabetes (duration of 1–18 y); active diabetic foot ulceration (duration of 1‐4 y) | Semi‐structured face‐to‐face interviews | 19 |

| Johnson (2005)48 | United Kingdom | Hospital‐based diabetic foot clinics | To investigate how patients and professionals view the role of advice in diabetes foot care in order to inform educational practice | 15 | 9 males, 6 females | 30‐70+ y | Type 1 (n = 7) or type 2 (n = 8) diabetes; diabetes‐related foot complications | Semi‐structured face‐to‐face interviews using a vignette technique | 16 |

| Johnson (2006)49 | United Kingdom | Hospital‐based diabetic foot clinics | To identify and discuss patient and health professional views of the use of therapeutic footwear for people with diabetes‐related foot complications | 15 | 9 males, 6 females | 30–70+ y | Type 1 (n = 7) or type 2 (n = 8) diabetes; diabetes‐related foot complications; long‐term experience of foot care services | Semi‐structured face‐to‐face interviews using a vignette technique | 16 |

| Kinmond (2003)50 | United Kingdom | Diabetic foot clinic | To address the lack of research relating to both psychosocial health‐related quality‐of‐life issues for patients living with diabetic foot ulceration and the limited number of studies that reflect patients' perspectives | 21 | 15 males, 6 females | Mean age = 58.9 y | Non‐insulin‐dependent (n = 8) or insulin‐dependent (n = 13) diabetes (6 mo‐27 y in duration); active diabetic foot ulceration | Semi‐structured interviews | 18 |

| Marchand (2012)51 | France | Diabetes Centre of a university hospital Centre | To investigate whether there are cognitive factors that act as barriers to the implementation of foot‐related preventive and curative behaviours by persons with diabetes at risk of foot complications | 30 | 30 males | Mean age = 63.8 ± 7.9 y | Type 2 diabetes (mean duration of 17.2 ± 8.9 y); history of previous chronic foot ulcer (lasting more than 3 wk) that occurred and healed at least 1 y prior to the start of the study [recurrence in previous 12 mo (n = 17); no recurrence in previous 12 mo (n = 13)] | Concept maps and semi‐structured face‐to‐face interviews | 17 |

| Matwa (2003)52 | South Africa | Diabetic clinic in a rural hospital | To explore and describe the experiences and foot care practices of diabetic patients who live in the rural areas of Transkei | 15 | 10 males, 5 females | 30–74 y | Diabetes (duration of at least 6 mo); with or without foot complications | In‐depth face‐to‐face interviews | 19 |

| McPherson (2002)53 | United Kingdom | Diabetic foot clinic | To examine the perceptions of patients with diabetes regarding their chronic foot ulcers | 4 | 4 males | Not reported | Type 1 diabetes; receiving treatment for foot ulcer for at least 6 mo | Focus group | 17 |

| Moreira (2010)54 | Brazil | Recruited through participation in previous research | To comprehend individuals with diabetes' experiences when dealing with a podological complication in their being‐in‐the‐world | 8 | Not reported | 18+ y | Diabetes; diabetic foot ulceration with or without amputation | Face‐to‐face interviews | 17 |

| Nancarrow (2003)55 | Australia | Podiatry services within the Australian Capital Territory | To identify the pathways that led to amputation or ulceration and the consequences of foot complications on the individual and the carer | 13 | Not reported | Not reported | Diabetes; diabetic foot ulcer or amputation in previous 6 mo | In‐depth interviews | 10 |

| Parry (1996)56 | United States | Urban orthopaedic limb care outpatient clinic serving low‐income population | To examine health beliefs and actions relating to the care of plantar ulcers in African Americans with type 2 diabetes | 20 | 7 males, 13 females | <40 y (n = 2), 40–50 y (n = 4), 50–60 y (n = 7), 60–70 y (n = 7). | Type 2 diabetes; undergoing treatment for diabetic foot ulceration | Open‐ended interviews | 12 |

| Paton (2014)57 | United Kingdom | National Health Service podiatry clinics | To explore the psychological influences and personal experiences behind the daily footwear selection of individuals with diabetes and neuropathy | 4 | 2 males, 2 females | 58–84 y | Diabetes (duration of 8–20+ y); peripheral neuropathy; history of foot problems (ranging from blisters to minor amputation); supplied with therapeutic insoles/footwear at least 6 mo previously | Semi‐structured face‐to‐face interviews | 18 |

| Ribu (2004)58 | Norway | Community (recruited through home care nurses) | To enhance understanding of the patient's perspective of living with lower‐extremity ulcers and diabetes | 7 | 4 males, 3 females | 21–83 y (median = 70 y) |

Type 1 (n = 1) or type 2 (n = 6) diabetes; one or more leg or foot ulcers (duration of 8 wk‐6 y) [Charcot foot (n = 1); amputated toes (n = 2); amputated leg (n = 1)] |

Semi‐structured face‐to‐face interviews | 16 |

| Ribu (2004)59 | Norway | Community (recruited through home care nurses) | To explore the nursing care experienced by patients with diabetes who have a foot and/or leg ulcer/illuminate the experiences of patients with diabetic foot and/or leg ulcers in order to clarify their needs | 7 | 4 males, 3 females | 21–83 y | Type 1 (n = 1) or type 2 (n = 6) diabetes; foot or leg ulcer (duration of 6 mo‐6 y) [foot ulcer (n = 4), leg ulcer (n = 2), foot and leg ulcer (n = 1)] | Semi‐structured face‐to‐face interviews | 13 |

| Searle (2005)60 | United Kingdom | Outpatient podiatry clinics | To explore the experience of foot ulceration and treatment from both the perspective of both patients and podiatrists | 13 | 9 males, 4 females | 45–66 y | Type 1 (n = 5) or type 2 (n = 8) diabetes (3–47 y in duration); active diabetic foot ulceration | Semi‐structured interviews | 15 |

| Searle (2008)61 | United Kingdom | Large health Centre serving inner‐city population | To explore the psychological and behavioural factors that may influence both the incidence of chronic wounds and their progression |

Study 1: 18 Study 2: 26 |

Study 1: 9 males, 9 females Study 2: 17 males, 9 females |

Study 1: Mean age = 64 y Study 2: Mean age = 67 y |

Study 1: Type 2 diabetes; no history of diabetic foot ulceration Study 2: Type 1 (n = 8) or type 2 (n = 18) diabetes; presenting with a first‐time ulcer or new episode of ulceration |

Semi‐structured face‐to‐face interviews | 13 |

| Vedhara (2012)62 | United Kingdom | Specialist podiatry services in secondary care | To qualitatively evaluate a psychological intervention designed to modify the psychosocial risks associated with foot re‐ulceration in individuals with diabetes | 8 | 6 males, 2 females | 56–81 y | Type 1 (n = 2) or type 2 (n = 6) diabetes; discharged with a healed diabetic foot ulcer in previous 12 mo | In‐depth qualitative interviews conducted at the end of the first 10 wk of the intervention and again following the final maintenance session | 16 |

| Watson‐Miller (2006)63 | Bermuda | Wound care unit and general surgical wards | To explore participants' experience with diabetic foot ulceration in Bermuda | 6 | 3 males, 3 females | 28–66 y | Diabetes; diagnosed with diabetic foot ulceration | Unstructured interviews | 16 |

| Wong (2005)64 | Australia | Two small communities in the Torres Strait and Northern Peninsula Area District | To achieve a better understanding of the perspectives and needs of indigenous people with diabetes in the Torres Strait and to identify ways to promote successful self‐management of diabetes | 67 | 26 males, 41 females | 30–70+ y | Diabetes; no information on DFU status | Focus groups (n = 67) and/or individual interviews (n = 30) | 15 |

CASP, Critical Appraisal Skills Programme; DFU, diabetic foot ulceration; GP, general practitioner.

3.3. Quality assessment

CASP total scores for each paper are provided in Table 1. The quality was good overall but varied considerably across papers, with scores ranging from 10 to 21 of a possible 24 (M = 16.43, SD = 2.81, median = 17). In the eight areas assessed, ratings were generally the lowest for reflexivity and highest for quality of findings and value of the research.

3.4. Data synthesis

Synthesis resulted in the identification of five overarching themes: (a) personal understandings of DFU, (b) prevention of DFU: knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours, (c) views on health care experiences, (d) development of DFU and actions taken, and (e) wide‐ranging impacts of DFU. These themes and their sub‐themes are outlined in Table 2, along with illustrative quotations from participants and a list of the papers that contributed to their development.

Table 2.

Qualitative synthesis: Themes, sub‐themes, and inclusion in papers

| Themes (third‐order constructs) | Sub‐themes | Key concepts (translated second‐order constructs) | Illustrative quotations from participants (first‐order constructs) | Studies that included subthemes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personal understandings of DFU | Identity | Limited awareness of what constitutes DFU |

Q: How would you describe a foot ulcer? What is it? A: Well, I don't … I'm not really sure to be honest. I couldn't describe it, not really. No, I'm not entirely sure what they are talking about, how to describe it. (Searle et al., 2008, p. 85) |

28, 31, 34, 40, 61 |

| Lack of knowledge regarding DFU appearance | I never knew I had an ulcer, because I didn't know what they looked like. I thought: “It's a bit of numbness.” It [foot] was a tiny bit red, I thought it was nothing much to really go to the doctor about. So I just hung on. (Beattie, Campbell & Vedhara, 2014, p. 434) | |||

| Cause | Limited understanding of link between diabetes and DFU | It never occurred to me sort of that it was diabetic related, really as far as I was concerned. As I said just got this hurt or this thing on my foot the same way you might have a mosquito bite that goes septic or whatever. You might bang into something and you got a bruise, something like that. So I really didn't think it was gonna be something serious. (Chithambo & Forbes, 2015, p. 23) | 24, 25, 26, 31, 34, 35, 36, 37, 40, 43, 45, 46, 51, 52, 56, 61, 64 | |

| Belief that DFU is because of poor circulation alone |

Interviewer: Why do you think it is that diabetes can affect the feet? Participant: The circulation goes, doesn't it? Well, I think it's the circulation. Because you do get like…I have got some, some of my toes, I haven't got much feeling in… (Gale et al., 2008, p. 558) |

|||

| Culturally specific beliefs regarding DFU | But let me warn you. Never leave your nails lying around, the witches use nails to make people develop ulcers. (Matwa, Chabeli, Muller & Levitt, 2003, p. 16) | |||

| Timeline | No history of ulceration: DFU as acute condition |

Interviewer: What do you think could happen if for instance you cut your toe on something sharp? Participant: Well, I would expect it to just heal up again I think. Obviously you'd need to sort of keep an eye on it, keep it checked, you know. (Gale et al., 2008, p. 559) |

32, 36, 39, 40, 43, 44, 45, 46, 51, 52, 55 | |

| History of ulceration: DFU as chronic condition | When I saw it I didn't think at all I just got mad…I felt sick…it begins with a little ulcer and at the end it will be a whole toe… it will never hea… I am in pain… (Hjelm, Nyberg & Apelqvist, 2002a, p. 676) | |||

| Consequences | Low perceived risk for DFU | I was aware that one can have foot ulcers but not that I could be affected because I have always tried to use correctly‐fitting shoes. (Hjelm, Nyberg & Apelqvist, 2003, p. 7) | 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 30, 31, 33, 34, 35, 36, 39, 40, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 51, 52, 53, 54, 56, 58, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64 | |

| Belief that DFU only occurs in acute cases |

Q: What sort of thing can it [infected foot wound] lead to? A: I would imagine if it was left long enough, gangrene and loss of either toe, or worse, your foot. So, um, I mean I think it would have to be very bad for that to happen but that is sort of the worst case scenario, then. (Searle et al., 2008, p.84) |

|||

| Judge others who develop DFU | I always keep my appointments, but like I say, if he thinks “Oh, it looks alright”, and he gets infection in it, it's his fault, it's his problem. (Johnson, Newton, Jiwa & Goyder, 2005, p. 330) | |||

| Belief that DFU will heal without medical intervention | I did not care about it because I had experienced a similar one before, which disappeared by itself. I thought this one would be so. (Abu‐Qamar & Wilson, 2012, p. 39) | |||

| Realise seriousness of DFU too late | [T]his nail that you always see in pictures or journals for diabetic people and so on, it is ridiculous… until you get a wound… then you understand what it is… you have to see what happens. (Hjelm, Nyberg & Apelqvist, 2002a, p. 676–7) | |||

| Fear of amputation | You're always, in the back of your mind, saying that one day you're going to lose the foot or they're going to amputate the foot. That's a big one always playing in the back of your mind. (Fox, 2005, p. 108) | |||

| Controllability | Low perceived control over DFU occurrence | I'm taking better care of my feet than I've ever done, and I'm still getting ulcers… sometimes your best isn't good enough, it'll happen anyway. I feel that the ulcers are defeating me and whatever I do, I feel like it's a lost cause. (Beattie, Campbell & Vedhara, 2014, p. 432) | 23, 24, 25, 26, 28, 29, 30, 31, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 51, 52, 55, 56, 57, 58, 60, 61, 62, 64 | |

| Sense of hopelessness | … like cancer, nobody gets completely cured. I am told that this (gangrenous left big toe) is caused by diabetes. All the people who had this thing never survived…cutting my leg will not change anything… (Matwa, Chabeli, Muller & Levitt, 2003, p. 16) | |||

| Uncertainty regarding the future | Are my feet going to go black? That's one of my worries. Are my toes going to go black, and I'll have to have them off? (Searle et al., 2005, online publication) | |||

| Negative outlook on future | “The future is not promising at all…having a dog leading you and having a stick and a wheelchair…those are complications you can get from diabetes…I am very worried…you get very scared…It is the fact that you know that you can get such wounds although you try to prevent it”. (Hjelm, Nyberg & Apelqvist, 2003, p. 11) | |||

| Preventing DFU: Knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours | Foot self‐care knowledge, engagement, barriers, and motivators | Knowledge of appropriate foot self‐care | Wear proper foot wear, when you have a shower make sure to check under your foot for cuts or anything like that, have your nails trimmed regularly. Rub moisturizing cream on your foot to make sure there are no rashes or dry skin. (Wong et al., 2005, p. 175) | 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 51, 52, 53, 55, 56, 57, 58, 60, 61, 62, 64 |

| Recognise importance of foot self‐care | Well, the bottom line, really, has always been cleanliness and I think that's very important where feet are concerned and particularly diabetic feet as well. So yes, that rates as very important to me. And I think that if people made the stipulation that they spent 10 minutes every day doing their feet it would save an awful lot of problems. (Gale et al., 2008, p. 558) | |||

| Know to seek medical assistance if foot injury occurs | Yes, any sore or cut you get, you should go straight to the Health Centre for dressing. It is very important. (Wong et al., 2005, p. 175) | |||

| Practice of appropriate foot self‐care | I wash my feet daily, I keep my nails short, ensure no injury is inflicted on the skin while cutting nails I put on cotton socks to reduce moisture and always keep spaces between toes, I clean and dry them. (Hjelm & Beebwa, 2013, p. 127) | |||

| Limited knowledge of appropriate foot self‐care | … the only thing I have been told is that I have to rub them [the feet] and to wipe them. I have not been given any advice. (Hjelm, Nyberg & Apelqvist, 2002b, p. 70) | |||

| Low perceived need for foot self‐care |

Interviewer: Do you sometimes put your hands inside your shoes to make sure there's nothing loose in there? Participant: No, I don't, that's the sort of thing I never think about, to be honest. Interviewer: No? Or that there's no grit inside them? Participant: Well, if there's grit, surely you can feel it, of course. (Gale et al., 2008, p. 560) |

|||

| Inconsistent engagement in foot self‐care | It's a load of old tosh isn't it? What would I want to check them [feet] every morning for? (Gale et al., 2008, p. 560) | |||

| Difficulty accepting diabetes | What happened was, about 5 or 6 years ago, I did something really stupid. I peeled some skin off the bottom of my foot. I knew I was diabetic, that's real stupid.…It went into complete sepsis, and, oh man, was I sick, but denial was the biggest problem with me.…You know, you think you can get away with cheating a bit with your food intake or your insulin or not taking your medications. (Fox, 2005, p. 107) | |||

| Lack of cues to action | Complacency sets in, yes… Diabetes is, if I break my arm, you can see that, put it in plaster and watch out but you can't see diabetes. So a broken arm, leg, you can see these things. But if it's in your blood, you can't see, feel or do anything. You have a tendency not to care about it so much, because it isn't actually a pain in the leg, it's not actually a toothache or an earache. (Burnside et al., 2007, p. 20) | |||

| Of lower priority than other aspects of diabetes self‐management | I've been told at the surgery [that foot care was very important] but I hadn't sort of… you know how they go on about, they go on about your diet, they go on about your cholesterol, they go on and you think, “Oh it's just another thing”, you know. (Gale et al., 2008, p. 557) | |||

| Physical and cognitive limitations | It's difficult for me because at the moment am having treatment because my eyes have gone bad as well, since I have been in hospital. Am partially sighted so I can barely see so it's difficult to try and look to see if I have any marks, it's not easy, so you know it's difficult. (Chithambo & Forbes, 2015, p. 22) | |||

| Education in foot self‐care from health professionals | You pick up lots of different advice from lots of different people, you know… (podiatrist) may well tell you about you socks being, you know “wear your socks inside out”… (Johnson, Newton, Jiwa & Goyder, 2005, p. 329) | |||

| Becoming empowered through foot care education | I learnt that you've got to really take care of your feet, and you've really got to do what you're told. I mean, I've had ulcers and things like that for many years and, you know, that's it. But if I hadn't got one, I never used to bother so much. I didn't have the knowledge I've got now to make sure they [feet] don't get bad. I think it was well worth it, and even old me learnt a lot from it [intervention]. (Vedhara et al., 2012, p. 329) | |||

| Assistance in foot care by family members | By myself, not very capable [at performing foot hygiene], with my companion completely capable. (Marchand et al.,2012, p. S139) | |||

| Provision of advice by family members | The sons used to say to me, “take care mum. It [diabetes] has effects on the feet.” (Abu‐Qamar & Wilson, 2011, p. 33) | |||

| Sense of personal responsibility | ….at the end of the day it's me who's responsible for my feet… (Vedhara et al., 2012, p. 330) | |||

| Prior experience as wake‐up call | I've lost this leg…I protect my foot because I don't want to lose another one. (Beattie et al., 2014, p. 435) | |||

| Learning from experiences of others | [At the hospital there was] a man in a wheelchair. And he'd lost from his knees down. And [my son] said to me “and that's how you'll end up with your diabetes”. And I think it registered in my mind. If you don't take care, you know that fear's there in the background all the time. (Searle et al., 2005, online publication) | |||

| Views on therapeutic footwear | Uncomfortable | The shoes they make are too heavy and are no good to me, but I can't make them understand that. (Bradbury & Price, 2011, p. 28)| | 27, 28, 29, 30, 32, 41, 43, 45, 49, 50, 51, 53, 55, 57, 60 | |

| Expensive | I have two pairs of them [diabetic foot wear] and they are expensive. I bought them 350 dollars [Barbadian; equivalent to USD 175] for a pair. You understand? So 700 dollars for two pairs of shoes. (Guell & Unwin, 2015, p. 330) | |||

| Concerns that prescribed footwear will put feet at risk | I'm petrified that when I start wearing them out [new orthotic shoes] it's going to start rubbing my feet. (Beattie, Campbell & Vedhara, 2014, p. 433) | |||

| Restrict activities | But um it's… it's… cumbersome I think is the way to describe it, it's cumbersome to walk in, it's very heavy to walk in, you can't walk great distances… especially if you are walking on anything that's any other than flat. (Burton, 2007, p. 20) | |||

| Unattractive | …there are a lot of hidden illnesses that you don't see and to end up with a clumsy boot, which is an ugly boot, you automatically focus on it. (McPherson & Binning, 2002, p. 201) | |||

| Cannot wear preferred choice of clothing | I used to wear floaty dresses. How can you put a floaty dress on and wear that? The other shoe I've got looks like a policeman's shoe. (Beattie, Campbell & Vedhara, 2014, p. 436) | |||

| Draw unwanted attention | [T]here were ever so many in Church that didn't know I was a diabetic, until I started wearing this big shoe; you don't want to broadcast it! (Johnson, Newton & Goyder, 2006, p. 170) | |||

| Undermine femininity | I went to a wedding on Sunday and had to wear trainers. I don't feel confident when I go out because I'm so used to dressing up in skirts, tights and high‐heeled shoes. I can't wear them at all now. (Ashford, McGee & Kinmond, 2000, p. 153) | |||

| Intentional non‐adherence | I think I'd rather continue with a small open wound that doesn't close, than having to wear some God forsaken shoe. I could wear trousers, but I like to wear skirts more…I'd rather live with my little ulcer and keep having dressings weekly than wear that shoe. (Beattie, Campbell & Vedhara, 2014, p. 436) | |||

| Functional value outweighs aesthetic concerns | If I didn't have shoes that I could wear and walk around in I couldn't function. (Paton, Roberts, Bruce & Marsden, 2014, p. 19) | |||

| Taking risks | Intentionally ignore foot care advice | They said you should really always wear shoes or slippers. Naughty girl that I don't. (Gale et al., 2008, p. 560) | 27, 28, 29, 30, 32, 33, 34, 37, 39, 40, 45, 46, 48, 49, 50, 52, 53, 56, 57, 58, 60, 61, 62 | |

| Intentionally wear inappropriate footwear | I forced my feet [into shoes] and then I went outside for 5 hours. Next day she [his wife] looked at my feet and said there were blisters, very big blisters. So it's my own mistake… (Kinmond, McGee, Gough & Ashford, 2003, p. 10) | |||

| Intentionally walk barefoot | I am told that I shouldn't walk barefoot. Walking, even from the bedroom to the bathroom without shoes on is bending the rules. But I do it very, very carefully… It's the only little risk I take. (Beattie, Campbell & Vedhara, 2014, p. 435) | |||

| Poor adherence to advice on resting ulcerated foot | I've been told the ulcer on my foot would probably heal a lot quicker if I didn't walk. Now so what? What am I gonna do, sit in a chair all day? I mean, it's not so much quantity of life it's quality… (McPherson & Binning, 2002, p. 200) | |||

| View that foot care impinges on lifestyle | I know what the answer is: if I get an ulcer… you keep your feet up. But again to do that, it's very awkward because you have still got to live. (Searle et al., 2005, online publication) | |||

| Taking strategic risks to maintain lifestyle | It is basically up to me. I notice that the more I sit still and the more I follow the advice I am given, the quicker it heals. But… you can't both sit and get everything done, too. (Ribu & Wahl, 2004a, p. 63) | |||

| Difficult to maintain appropriate behaviours in the long term | Having healed for me is the main thing… It's also keeping it up. At the moment it's still quite new and exciting. But I suppose you can get used to it and not take as much care. (Beattie, Campbell & Vedhara, 2014, p. 436) | |||

| Preferences for foot care education | Value of providing written information |

Q: Do you think it is best that information is given in writing, in leaflets, or are there other ways you can think of? A: Both actually, verbal and writing, because I do feel sometimes you don't have time to read it and you misplace it, you know, you can't find it. (Searle et al., 2008, p. 85) |

26, 31, 41, 42, 61, 62 | |

| Inclusion of graphic images of DFU | I greatly believe that it has to be graphic, people have to see what can happen to their feet if they don't take precautions. (Burnside et al., 2007, p. 22) | |||

| Value of group‐based interventions | You need to hear other people that have had problems, diabetic foot problems. Ulcers they've had in the past, okay they've come through but they've had that experience, they know about these things. Listening to the other members, you know, where things haven't been quite right, we've all had it. (Vedhara et al., 2012, p. 328) | |||

| Importance of reinforcing foot care education | It [follow‐up] was very good for reinforcing everything we had heard, learnt. You do get out of good habits. I think just an occasional reminder about what we are doing and why we are doing it. (Vedhara et al., 2012, p. 327) | |||

| Need for general information on diabetes as well as foot care | You've got to talk about diabetes, you've got to talk about medication, about what you eat. If you're going to talk about foot ulcers one relates to the other. (Vedhara et al., 2012, p. 327) | |||

| Reluctance to attend foot care education |

Q: But there are sorts of meetings… A: Yeah, but I wouldn't come […] Q: So you don't think it would give you anything? A: I don't think I'd learn any more than what I already know isn't it, because it's a common sense thing isn't it in the end. (Searle et al., 2008, p. 85) |

|||

| Barriers to attendance | Sometimes I get a bit on edge if I go to the hospital, with the waiting and that, you know. (Burnside et al., 2007, p. 22) | |||

| Views on health care experiences | Dissatisfaction with foot care provided | Foot examinations not routinely performed |

Researcher: Since being diagnosed in the 1980s, when you visited the doctor, were your feet examined, that is, did the doctor inspect the soles? Abu‐Salem: No, no, no. Researcher: No examination! So you mean that foot examination took place after the burn injury? Abu‐Salem's wife: Yes. Abu‐Salem: After this accident. (Abu‐Qamar & Wilson, 2011, p. 32) |

23, 24, 25, 26, 30, 32, 33, 34, 37, 38, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 58, 59, 61 |

| Limited advice on foot care | When I first got diabetes, my GP said you've got to be careful with your feet, and I said why? He said because it can affect your feet. That was all really. He said the nerves might go but he didn't say very much more about it, except be careful with your feet. (Chithambo & Forbes, 2015, p. 22) | |||

| Lack of attention to feet undermines perceived importance of foot self‐care | I would say, actually, if I'm honest with you, the feet side of things is something that always gets ignored. If your doctor and your nurse don't prioritise it, why should you? (Gale et al., 2008, p. 560) | |||

| Inconsistencies in care provided | They put dressing on it, and they gave me cream and they said you have to come to the outpatients clinic tomorrow. I was surprised they did not admit me as an emergency case. Next day, I came to see Dr. Saleem, who is the plastic surgeon; he got upset. He said you have infection, you need hospitalization. (Abu‐Qamar & Wilson, 2012, p. 40) | |||

| Dissatisfaction with care in hospital | To me, that room was a disease, there was nobody to talk to, for God's sake. It was like a dead place. I stayed in there for nine days, and for me it was like a year, a year! That is no place for a person to be… (Moreira & Sales, 2010, p. 899) | |||

| Sense of mistrust | I finished with the private doctors. “Cause I realised they were taking away my money and tellin” me that my feet is gettin’ better and then I end up in the hospital. (Guell & Unwin, 2015, p. 380) | |||

| Acknowledge limited availability of personnel and resources | They're doing the best they can with what they've got I say… It's just trying to get the government to put more money in I say and that'd be hard. (Delea et al., 2015, p. 255–6) | |||

| Financial costs associated with foot care | The wound has made me very poor, I expected help from health care staff, especially drugs and regular glucose monitoring, but nothing was given to me… I was advised to constantly check my blood glucose but it is not possible… each time you check that is money I don't have. (Hjelm & Beebwa, 2013, p. 127) | |||

| Accessibility issues | At the emergency health care centre they instructed me to schedule an appointment with the vascular doctor. I went to the city hall during lunch break and waited there for some time. I was close to crying I was in so much pain. I was able to schedule an appointment, but I remember that the employee responsible for the scheduling told me that the city bus that takes the patients to the appointment was full. (Moreira & Sales, 2010, p. 900) | |||

| Positive views on specialist services | Preferred to general practitioner care | I just think they [diabetes specialist nurses] know more, more than what the doctors know, and they know every crook and cranny, whereas your doctors, working on a general principle, whereas they are working, specialising… and they're friendly, more like a family basis… (Johnson, Newton, Jiwa & Goyder, 2005, p. 329) | 23, 24, 25, 29, 31, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 46, 47, 48, 53, 55, 61, 64 | |

| Regular appointments provide reassurance | I manage my toes… I go to X [chiropodist] so if I recognise that something is wrong, she will take care of it… it is better to let the expert manage it… it gives a great sense of security to know that you can visit chiropodists. (Hjelm, Nyberg & Apelqvist, 2002a, p. 677) | |||

| Limited access to specialist services | When the podiatrist saw me she said, “Who cuts your toenails?” I said “I do it myself”, and she said, “You shouldn't do it”, I said “Well I do it myself because you never come to see us”. That's why I lost my toe. You got to come and see us more often. (Wong et al., 2005, p. 175) | |||

| Dissatisfaction with patient‐provider communication | Poor communication | They talk to you like they're talking to kids; they talk down to you half the time. They don't explain things, they just come around [saying] “Well you'll have to have this done and that” and then go away. They don't explain things to you. (McPherson & Binning, 2002, p. 202) | 23, 24, 25, 26, 29, 32, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 43, 44, 46, 47, 50, 52, 53, 54, 56, 59, 60, 61, 63 | |

| Rushed appointments | It was very brief, very brief. Here you are, have an antibiotic, go away. As if, I mean whether she didn't think it was much either I don't know but she certainly gave the impression of not being concerned about it. Didn't want to refer it anywhere. I just went away, thank you for your prescription, goodbye. (Chithambo & Forbes, 2015, p. 24) | |||

| Insensitivity regarding need for amputation | “… he came into me one morning ‐ into the ward and he says, I'm going to take your leg off… He just frightened the life out of me… He didn't even introduce himself at all. Shock!” (Delea et al., 2015, p. 254) | |||

| Lack holistic view of patient | The nurses came in and they had a job to do, and you know, it was basically the foot and I'm not just a foot… It was hard to deal with and there was really no psychological support… There was no acknowledgement that your whole life has been affected. (Fox, 2005, p. 109) | |||

| Do not appreciate impact of DFU | I know Dr. X, when he says, “Go home and rest”, that is the answer, but there are certain other things you have got to do as well, you know, like earn a living! (Searle et al., 2005, online publication) | |||

| Underestimate seriousness of condition | I kept going to my GP and I kept asking them you know, do I need to go to the hospital? And they kept saying no, no it's fine, we just give you antibiotics, just come to the nurse. And it just got worse and worse and worse. (Chithambo & Forbes, 2015, p. 24) | |||

| Paternalistic nature of patient‐provider relationship | It's that syndrome again, you're a human being but you sit there and you've got a number and everybody else talks right over the top of your head. They don't give a thought to the fact that you might have a brain cell of your own. (Searle et al., 2008, p. 88) | |||

| Passivity in health care encounters | They probably can't do any more. I have received the care they can give me for the wound, I assume… so I trust what has been done. (Ribu & Wahl, 2004b, p. 67) | |||

| Desire for more holistic care | Importance of good rapport | They do know what they are doing and, at least those who have been here and whom I have experienced, have been very pleasant and seem very interested in progress taking place in the treatment and that it is going better and such. So, that is I guess what I would have said, yes, that they are not just like that, that they come and change the dressing and then leave, that there are other things that go with it and such. (Ribu & Wahl, 2004b, p. 67–68) | 29, 37, 39, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 54, 58, 59, 61 | |

| Interest in emotional as well as physical well‐being | There was one nurse… she sat with me and gave me comfort. Now that is something that you cannot get with swallowing a pill. (Bradbury & Price, 2011, p. 30) | |||

| Importance of empathy, understanding, and open communication | [Description of ideal physician/nurse] Attending to my problems, discussing them, listening and being keen to listen to me, diagnosing and taking measures, being easy to talk to, being able to give and take information as well as being highly skilled in medicine… and creating a gentle and positive attitude. (Hjelm, Nyberg & Apelqvist, 2002b, p. 71) | |||

| Development of DFU and actions taken | Pathways to DFU | DFU because of burn injury | At night, I put my toe on the radiator…in the morning there was a cavity…my toe was swollen and hurt. (Abu‐Qamar & Wilson, 2011, p. 37) | 23, 24, 25, 27, 28, 34, 35, 36, 39, 43, 44, 45, 46, 48, 50, 51, 52, 53, 55 |

| DFU because of inappropriate footwear | One of the doctors had said that she should wear sneakers to support her feet. Because she didn't sleep she was walking and pacing and that's when the sneakers actually rubbed and caused the ulcer. (Nancarrow & Devlin, 2003, p. 198–9) | |||

| DFU because of foot injury | I scratch with my nails but I go too far, then it bleeds, it makes it sore. (Marchand et al., 2012, p. S136‐7) | |||

| DFU because of failed self‐treatment of wound | I do not know its name; it is one of those ordinary creams. After using it, it caused infection, my toe blackened and the infection started to spread to other parts. (Aliasgharpour & Nayeri, 2012, p. 31) | |||

| Discovery of DFU | Numbness in feet delays discovery | I had trodden on a nail…I didn't recognise it until in the evening when I was taking off my shoe and my stockings were stained with blood… (Hjelm, Nyberg & Apelqvist, 2002, p. 676) | 23, 34, 37, 39, 43, 44, 45, 47, 50, 51, 53, 60, 62 | |

| Discovery by family members | I did not feel anything, my sister in law told me that my leg was swollen. (Abu‐Qamar & Wilson, 2012, p. 38) | |||

| Shock and anger on discovery | When I saw it I didn't think at all, I just got mad…I felt sick… (Hjelm, Nyberg & Apelqvist, 2002, p. 676) | |||

| Surprise at speed of deterioration in condition of foot | What is scaring is…that it (the previous time) went so extremely fast…after two days they established that they had to amputate the feet. (Hjelm, Löndahl, Katzman & Apelqvist, 2009, p. 1982) | |||

| Decisions regarding DFU treatment | Delay in seeking medical attention | It started out as a little scratch…so I didn't attend to it as urgently as I should have. I went away to the Caribbean for 3 weeks instead of going to the doctor to get it attended to… By the time I got back [to Canada], the foot had swollen to about twice the size.” (Fox, 2005, p. 107) | 23, 25, 27, 28, 31, 33, 34, 35, 36, 38, 39, 43, 45, 46, 47, 52, 56, 64 | |

| Lack of pain leads to underestimation of seriousness of foot wound | I had these enormous blood blisters on the bottom [of] each foot… [I thought]: “I'll just keep an eye on these for now”, because I wasn't getting any pain. I treated them [with] antiseptic wiping… and left it for so long. I didn't feel it was bad enough for me to be panicking over it.” (Beattie, Campbell & Vedhara, 2014, p. 434) | |||

| Self‐treatment of DFU | I do not know its name; it is one of those ordinary creams. After using it, it caused infection, my toe blackened and the infection started to spread to other parts. (Aliasgharpour & Nayeri, 2012, p. 31) | |||

| Religion/prayer to heal wound | I had cracked feet since 1993. I used prayer and my cracked feet came okay from prayer. This is my inner secret. (Wong et al., 2005, p. 175) | |||

| Culturally specific treatments for DFU | If it were not for my “inyanga” [traditional healer] I would not be talking to you now. So if it was diabetes, why didn't the doctor help it, and yet a black man did? (Matwa, Chabeli, Muller & Levitt, 2003, p. 16) | |||

| Wide‐ranging impacts of DFU | Physical impact | Pain | The wound started on a toe…and went to affect the whole foot and the leg. It was so painful that it would not allow me to move… (Hjelm & Beebwa, 2013, p. 126) | 27, 28, 29, 30, 32, 36, 37, 38, 39, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 58, 60, 61, 62, 63 |

| Reduced mobility | When you stop to think about it you could just get up and go and now you can't; you're restricted; you have to take care not to knock your leg; you have to be careful that you don't tread on anything that you know is on the ground. (Kinmond, McGee, Gough & Ashford, 2003, p. 10) | |||

| Sleep disturbances | I had to lie a certain way, had to lie on my right side and then I had to place the leg parallel on top and then I lay on my side like that, then I wasn't in pain, but when I twisted my foot like that, it was so damn painful, excuse me… it was so awful that I had to stand up, I couldn't manage to lie down like that, had to get on the floor, sit on the edge of the bed, and move the leg. (Ribu & Wahl, 2004a, p. 62) | |||

| Cyclical pattern of healing and recurrence | Another operation… debride it, cleaned it all out… form that day onwards I've spent three Christmases out of five in there… all with the same problem… it goes all right and then it gets a build‐up. (Burton, 2007, p. 18) | |||

| DFU care is time‐consuming | I'd have to go in and inform work that I'd need every Monday [to] finish at 3 o'clock, or every Wednesday I wouldn't be in until 11 o'clock so I could get to the clinic… (Beattie, Campbell & Vedhara, 2014, p. 435) | |||

| DFU care dominates life | Your foot controls your everyday workings… well, controls your life, really, your feet, doesn't it? (Searle et al., 2005, online publication) | |||

| Social and vocational impact | Lifestyle restrictions | It means a disrupted lifestyle for however long it takes for that to mend. You have to start altering your life to that then. (Beattie, Campbell & Vedhara, 2014, p. 435) | 23, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 32, 35, 37, 38, 39, 43, 44, 45, 46, 50, 51, 52, 53, 55, 56, 58, 60, 63 | |

| Leisure activities curtailed | I used to be a field sports person and now [pause] I can't walk far. (McPherson & Binning, 2002, p. 199) | |||

| Difficulty in fulfilling social roles | You know you miss the things you do with your grandchildren… I mean his other nan took him to feed the ducks and things. And it choked me because I thought, well, I should be doing that as well. (Kinmond, McGee, Gough & Ashford, 2003, p. 10) | |||

| Social isolation | In the middle of all of this, I have become so isolated. If I did not have this [ulcer], I would get out more, and not sit inside so much and ponder and think. (Ribu & Wahl, 2004a, p. 62) | |||

| Stigma associated with DFU | I think it's just one of those things that you don't particularly want to discuss with friends… I think some people associate ulcers with being a nasty, smelly old wound… (Beattie, Campbell & Vedhara, 2014, p. 434) | |||

| Loss of employment | Because I was in the building industry wearing steel toe‐capped boots, the consultant said, “You've got to pack the job in”. Well, I said, “What am I going to do?” “I don't know”, he said, “but you can't go back wearing those boots”. (McPherson & Binning, 2002, p. 200) | |||

| Financial hardship | Oh 100 grand… lost income. The wife works and I have a few bob stashed away, financially these episodes cost you… Keeping a house running costs money and I have nothing coming in and everything going out. (Nancarrow & Devlin, 2003, p. 196) | |||

| Psychological impact | Anxiety | I get anxious, worried, it [DFU] really does take over my life. Because I immediately start to think of things I can't do…Just walking out to the kitchen, it's simple things like standing [to put the kettle on]. (Beattie, Campbell & Vedhara, 2014, p. 433) | 25, 27, 28, 29, 30, 32, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 50, 53, 54, 57, 58, 60, 62, 63 | |

| Reduced quality of life | I think I have poorer quality of life…one doesn't have the energy any longer. (Hjelm, Nyberg & Apelqvist, 2002a, p. 676) | |||

| Loss of self‐esteem |

Interviewer: Do you think it affects your self‐esteem? Patient: Oh, I think so. Interviewer: In what way? Patient: I don't know… you feel down all the time I think… gets you a bit depressed I suppose at times, and I just don't want to bother. (Searle et al., 2005, online publication) |

|||

| Altered sense of self | My wife goes out and gets the benefits as the major income earner, with me being at home tying up loose ends. It was hard for me to get adjusted because I didn't feel like it was my place. And to tell you the truth, I'd rather be working. (Fox, 2005, p. 108) | |||

| Anger and frustration over loss of independence | I've lived on a shelf for 3 years. I've really run out of kind thoughts and patience. You know it's okay [for the clinic] to say “Come back in a month,”…and I'm still stuck like a bug on a pin. That's how it feels: living without living. (Fox, 2005, p. 108) | |||

| Sense of powerlessness | You get frustrated when you sit around like that, you feel powerless, everything becomes so heavy. (Ribu & Wahl, 2004a, p. 62) | |||

| Depressed affect | I've just been like a zombie. With no interest. (Bradbury & Price, 2011, p. 42) | |||

| Guilt and self‐blame | …that's my punishment, I was trying to do my life and pretend I wasn't diabetic. (Beattie, Campbell & Vedhara, 2014, p. 433) | |||

| Regret over not looking after feet better | … how could I know the possibility of facing such miseries? … if I have controlled it, this would have been different. (Aliasgharpour & Nayeri, 2012, p. 32) | |||

| Sense of acceptance | It gets easier because you're adjusted to it, you've got a problem and you've got to get through it… (McPherson & Binning, 2002, p. 201) | |||

| Positive outlook | [I]t will be fine again… my wishes are now when it has been stabilized that I will be able to live a rather good life anyhow. (Hjelm, Nyberg & Apelqvist, 2002b, p. 73) | |||

| Perceived benefits | I think differently…Often when you have gone through something, something serious… often you become a stronger person… you can look forward in another way. (Hjelm, Nyberg & Apelqvist, 2003, p. 7) | |||

| Sources of support and impact on relationships | Emotional support from friends and family | Whenever I'm feeling peaked, I call a close friend of the family who is 90 years old. She always tells me what to do for me and my children and it makes us better. (Parry, Mobley & Allen, 1996, p. 270) | 23, 27, 28, 29, 30, 36, 37, 38, 39, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 50, 53, 55, 56, 58, 60, 62, 63 | |

| Practical support from friends and family | If anything is worrying me I know I can ask my wife or my daughters to have a look at my feet. Most friends are very good. If [names wife] got a problem picking me up from work, they [will] pick me up. (Beattie, Campbell & Vedhara, 2014, p. 434) | |||

| DFU care from community health services | And under my heels I have fissures…the health care staff over there [district nurse and home care staff at service apartments] rub my feet with ointment every day. (Hjelm, Nyberg & Apelqvist, 2002a, p. 677) | |||

| Alternative sources of support | Whenever I'm not feeling up to anything, I call my children or church members and they come and see about me. (Parry, Mobley & Allen, 1996, p. 270) | |||

| Support from fellow DFU patients | Oh I get on very well with the other diabetic I know down at the [hospital]. I know quite a few, because we do see each other on a Tuesday or Friday or whatever. We knows all, and we all have the same bad shoe treatment like the little flat sandal with the things that flap over the top. We've all had ulcerated toes. (Searle et al., 2005, online publication) | |||

| Sense of being a burden on others | Ulcer has caused me lots of problems because I am now totally dependent on other people who look on me as a burden. (Hjelm & Beebwa, 2013, p. 127) | |||

| Strained relationships with family members | My children are helping me all the time. My wife cannot sleep. In the night‐time I call her two or three times… My whole family is suffering. (Kinmond, McGee, Gough & Ashford, 2003, p. 12) | |||

| Reluctant to discuss experiences with others | It's not a fun subject. I wouldn't really burden my friends with it [DFU]…when I was worried most about it I didn't talk to anyone too much… (Beattie, Campbell & Vedhara, 2014, p. 434) | |||

| Insufficient support provided | If they wanna ring, the phone's there. I mean I ain't gonna spend hours and hours talking to them every day of the week, but it ain't going to change the fact that they never done it, and I can't see them starting it now. (Searle et al., 2005, online publication) | |||

| Others underestimate seriousness of DFU | The family and friends, no they didn't understand at all. “He might be having it on”. My sister she was like: “Oh, he's just sitting around… sat around with his foot up in the air”… My boss said: “You've got a sore foot, that's all it is”. You just can't explain, they don't know, it's ignorance again. (Beattie, Campbell & Vedhara, 2014, p. 434) | |||

DFU, diabetic foot ulceration; USD, United States Dollar; GP, general practitioner.

3.4.1. Personal understandings of DFU

Several papers explored participants' knowledge and perceptions of DFU, which revolved around its identity, cause, timeline, consequences, and controllability. Overall, participants' comprehension of DFU was often either limited or erroneous. This had the effect of impeding attempts at self‐care and resulted in participants exposing their feet to greater risks in some cases.

Identity

Some participants, including those with previous28, 31, 34 or active61 ulceration, lacked awareness as to what DFU is or looks like.28, 31, 34, 40, 61 This hindered foot self‐care28 and delayed both ulcer detection28, 34, 61 and seeking of medical attention,28, 34 putting the foot at increased risk for negative sequelae.

Cause

Participants' beliefs regarding DFU causation often conflicted with conventional medical understanding of this condition. Many were unaware, or had limited knowledge, of the role diabetes plays in DFU aetiology, irrespective of their ulceration status.24, 25, 26, 31, 34, 35, 36, 37, 40, 43, 45, 46, 51, 52, 56, 61, 64 Some only received a diagnosis of diabetes on presenting with an ulcer,24, 25, 56 while others did not become aware of the relationship between diabetes and foot problems until seeking treatment for ulceration.37 Several participants cited poor circulation as the primary cause of DFU/amputation.26, 31, 36, 40, 43, 45, 56, 61 Loss of sensation from peripheral neuropathy was sometimes misinterpreted as reduced blood flow to the feet,40, 56, 61 leading to misunderstandings regarding the purpose of tests to assess peripheral sensation61 and misguided attempts to increase circulation by walking barefoot or wearing open‐toed sandals, which inadvertently put them at an increased risk of foot injury.40, 61 Some participants described culturally specific beliefs they held about DFU causation that diverged from medical explanations of this condition.51, 52, 56, 64

Timeline

There was some evidence that individuals who had no prior experience of ulceration viewed DFU as an acute condition that would heal quickly,34, 39, 40, 46, 58, 60 whereas those with previous or active ulcers viewed healing as a prolonged, or indefinite, process.32, 36, 39, 43, 44, 45, 46, 51, 52, 55, 61

Consequences

Many participants were either unaware of, or unconcerned about, their risk of diabetes‐related foot problems.24, 25, 26, 27, 31, 33, 34, 39, 40, 42, 48, 51, 53, 56, 61 Some believed that DFU and amputation only occurred in acute cases24, 61 or instances of poor hygiene40 and were critical of individuals who neglected themselves to such an extent.35, 40, 48 It was apparent that many individuals did not consider cuts or sores on the foot to be a cause for concern40, 45, 46, 52, 61 and believed they would heal easily without medical intervention.23, 34, 39, 40, 45, 46, 52, 61 Those with a history of ulceration acknowledged that they had failed to grasp the potential seriousness of DFU before it was too late.28, 34, 39, 48, 58, 61, 62 However, some individuals with no prior experience were aware of the risks and feared developing an ulcer.35, 52 Fear of amputation was also frequently reported,26, 28, 30, 33, 35, 36, 39, 40, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 52, 54, 58, 60, 61, 63, 64 especially among those who either had personal experience of DFU26, 28, 30, 33, 36, 39, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 54, 58, 60, 63, 64 or knew someone who had undergone this procedure.33, 39, 40, 52, 60, 61, 64

Controllability

Many individuals had limited perceived control over DFU, particularly those with previous or current ulcers, and felt that little could be done to prevent DFU occurrence26, 28, 39, 43, 44, 45, 46, 51, 52, 58, 60, 61 or were unaware that there were different stages at which action could be taken,26, 44, 45, 46, 61 leading to a sense of hopelessness and resignation.26, 28, 39, 43, 44, 45, 46, 51, 52, 58, 60 Participants in several papers, especially those with a history of ulceration,26, 28, 30, 36, 38, 39, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 51, 54, 58, 60 expressed uncertainty28, 30, 36, 38, 39, 46, 47, 51, 54, 58, 60 or had a negative outlook26, 38, 39, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 52, 58 regarding the future.

3.4.2. Preventing DFU: Knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours

Participants' knowledge of, attitudes towards, and engagement in behaviours that prevent DFU were examined across papers. It was apparent that even when knowledge of appropriate foot care behaviours was present, perceived barriers, such as their impingement on everyday activities, precluded adherence.

Foot self‐care knowledge, engagement, barriers, and motivators

Varying levels of knowledge and engagement in foot self‐care were reported by participants. Many recognised the importance of maintaining healthy feet and avoiding DFU28, 34, 35, 36, 39, 40, 43, 44, 45, 46, 52, 61, 62, 64 and demonstrated good awareness of appropriate behaviours,25, 26, 28, 35, 36, 37, 43, 44, 45, 46, 51, 52, 61, 62, 64 such as seeking immediate medical assistance for foot injuries.28, 31, 33, 35, 36, 40, 43, 44, 45, 46, 51, 61, 62, 64 These individuals tended to practice foot self‐care regularly.28, 30, 31, 35, 36, 40, 43, 45, 46, 47, 51, 52, 61, 62, 64 Others, however, lacked even a basic knowledge of,25, 33, 43, 45, 46, 52, 61, 64 or perceived little need for,24, 25, 26, 27, 31, 33, 40, 48, 52, 61 preventive action; their behavioural performance was often limited or inconsistent at best.26, 40, 45, 46 Several factors appeared to impede engagement in foot self‐care, in addition to participants' misperceptions of DFU outlined in the previous theme. Some disregarded foot self‐care recommendations as they had difficulty accepting their diabetes.26, 28, 33, 39, 44, 48, 52 For others, the lack of visible symptoms and gradual onset of this “silent disease”35 provided few cues for action, leading them to become complacent about their feet.24, 31, 35, 43, 44, 48, 58 As one of several self‐management practices required of people with diabetes, foot self‐care was often considered of lower priority than more immediate demands (eg, taking medication, monitoring blood sugar).26, 41, 61 Physical and cognitive limitations, such as poor eyesight,34, 35, 43 problems remembering,26, 33, 40, 61 or difficulty reaching feet,26, 35, 51, 64 also posed challenges in performing foot self‐care unaided. Factors that appeared to motivate engagement in foot self‐care included receipt of education and/or training from health professionals,25, 31, 33, 34, 35, 37, 42, 43, 45, 46, 48, 51, 55, 57, 61, 62 which empowered participants to look after their feet.26, 37, 41, 43, 45, 46, 47, 48, 51, 62 Family members were also pivotal in promoting foot self‐care by providing advice23, 24, 33, 35, 43, 46, 51, 55, 56, 61 and practical assistance.23, 29, 34, 35, 36, 43, 44, 45, 62, 64 Having a greater sense of personal responsibility for one's feet appeared to encourage more proactive care.26, 35, 36, 39, 41, 43, 45, 51, 52, 61, 62 Personal experience of foot complications28, 30, 31, 35, 39, 43, 45, 46, 57, 58, 61, 62, 64 often served as a “wake‐up call”28 to initiate positive behavioural changes, although knowing or observing others who have experienced DFU or amputation had a similar effect.33, 38, 39, 40, 52, 56, 60, 61, 62, 64

Therapeutic footwear views and practices

Many individuals expressed frustration with wearing prescribed footwear and other orthotic devices,27, 28, 29, 30, 32, 49, 50, 53, 57, 60 which were found to be expensive30, 41, 43, 45, 55 and uncomfortable.28, 29, 30, 32, 49, 55, 60 Some experienced such pain and discomfort that they feared they were putting their feet at increased risk of DFU.28, 29, 32, 49 Others reported severely restricted lifestyles.32, 51, 53, 57, 60 The bulky, unattractive appearance of therapeutic footwear was also remarked upon27, 28, 30, 32, 43, 49, 53, 57, 60 as it prevented people from wearing their preferred choice of clothing27, 28, 32, 49, 50, 60 and drew unwanted attention.28, 32, 49, 53, 57 Female participants described how the “diving boot”‐like57 appearance of their footwear impacted their sense of femininity27, 28, 49, 50, 57, 60 and self‐confidence,27, 50, 60 particularly on social occasions. These factors led many individuals to intentionally defy therapeutic footwear guidelines,28, 32, 49, 53, 57, 60 although for some, their functional value ultimately outweighed any aesthetic concerns.32, 43, 49, 57

Taking risks

Participants across studies admitted to taking chances with their foot health. Many purposely ignored foot self‐care advice,27, 28, 33, 37, 39, 45, 48, 56, 62 while others knowingly engaged in hazardous behaviours such as wearing inappropriate footwear,27, 28, 29, 40, 46, 49, 50, 57, 60, 62 walking barefoot,28, 40, 46, 52, 62 and disregarding instructions to rest the ulcerated foot.30, 48, 50, 53, 58, 60, 61 This was especially the case when recommended actions impinged on everyday activities, with participants taking strategic risks to maintain as normal a life as possible.28, 30, 32, 34, 39, 45, 48, 49, 50, 53, 57, 58, 60, 62 Even those who did adhere to foot care recommendations acknowledged that they might struggle to do so in the long term.28, 62

Preferences for foot care education

Attitudes towards foot care education were generally positive, where explored.42, 61, 62 Four papers examined participants' preferences concerning the form this education should take.26, 31, 61, 62 The value of providing information that was clear, practical, and positively framed,26, 31 preferably in the form of leaflets that could be taken home and kept for reference,26, 31, 61 was emphasised. Although it was acknowledged that the inclusion of graphic images of foot ulcers could induce fear,26, 31 some felt this was necessary to motivate behavioural change.31 Views were mixed regarding whether foot care education should be provided on an individual or group basis. Individuals who took part in Vedhara and colleagues'62 intervention were receptive to its group‐based format, which provided them with the opportunity to share with and learn from others; conversely, most participants in Burnside and colleagues' study31 expressed a preference for one‐to‐one sessions. With regard to timing, some believed education should be provided shortly after the diagnosis of diabetes,31, 42 although the value of further sessions to reinforce learning was highlighted.42, 62 Participants in two studies suggested that general information on diabetes should be provided before focusing on foot care.31, 62 Some individuals admitted they were unlikely to attend foot care education despite being aware of its importance.31, 61 Barriers to attendance included work and child care commitments, mobility issues, financial constraints, and a dislike of hospitals as a venue.31

3.4.3. Views on health care experiences

Participants across studies expressed dissatisfaction with elements of their health care experiences regarding DFU and voiced a desire for more holistic care.

Dissatisfaction with foot care provided