Abstract

The sacral region is the most common site for pressure injuries (PIs) associated with lying in bed, and such sacral PIs often commence as deep tissue injuries (DTIs) that later present as open wounds. In complex patients, diabetes is common. Because, among other factors, diabetes affects connective tissue stiffness properties, making these tissues less able to dissipate mechanical loads through physiological deformations, diabetes is an additional biomechanical risk factor for PIs and DTIs. A preventive measure with established successful clinical outcomes is the use of sacral prophylactic dressings. The objective of this study has been to expand our previous work regarding the modes of action and biomechanical efficacy of prophylactic dressings in protecting the soft tissues adjacent to the sacrum by specifically examining the role of a directional stiffness preference (anisotropy) of the dressing while further accounting for diabetic tissue conditions. Multiple three‐dimensional anatomically detailed finite element (FE) model variants representing diabetic tissue conditions were used, and tissue loading state data were compared with healthy tissue simulations. We specifically compared soft tissue exposures to elevated internal shear stresses and strain energy densities (SED) near the sacrum during supine weight bearing on a standard (foam) hospital mattress without a dressing, with a prophylactic dressing lacking directional stiffness preferences and with an anisotropic dressing. Our results have clearly shown that an anisotropic dressing design reduces the peak tissue stresses and exposure to sustained tissue deformations in both healthy and diabetic cases. The present study provides additional important insights regarding the optimal structural and material design of prophylactic dressings, which in turn, informs clinicians and decision makers regarding beneficial features.

Keywords: Computational modelling, Deep tissue injuries, Finite element analysis, Prophylactic dressings, Sacral pressure injuries

Introduction

Pressure ulcers, now formally termed pressure injuries (PIs) in the USA and Australia, are localised sites of tissue damage, usually near a bony prominence (unless caused by contact with a medical device) 1. The sacral area is the most common site for PIs associated with lying in bed, and such sacral PIs often commence as deep tissue injuries (DTIs) that later present as open wounds, often a full‐thickness wound affecting all tissue layers down to the bone 2, 3. In complex patients, diabetes is common, and because diabetes affects connective tissue stiffness properties, causing these tissues to become stiffer due to the formation of advanced glycation end‐products and thickening and inter‐linking collagen fibres 4, diabetic connective tissues are less able to distribute mechanical loads through deformation. This diabetic tissue stiffening effect was demonstrated in both animal models and human tissue specimens, is mechanically evident at a macroscopic level and is well‐established 5, 6. Its direct biomechanical outcome is elevated tissue stresses in weight‐bearing connective diabetic tissues, which is an additional risk factor for PIs and DTIs in these patients, on top of the contributions of impaired inflammation response, compromised perfusion and, overall, a diminished tissue repair capacity. In this context, it is worthwhile to note that diabetes also affects the sensory inputs, muscular and joint function and the overall ability of a diabetic patient to detect discomfort and pain and respond to those in a timely manner by micro‐ or macro‐movements and postural changes. All these factors sum up and add to the cumulative risk for developing PIs and DTIs in patients with diabetes.

While a patient is in bed, the soft tissues surrounding the sacrum are subjected to compound loading with compressive, tensional and shear components. The exposure of skin and deep tissues to shear and their resulting distortion can escalate in common hospital scenarios, such as when a patient is being moved (or dragged) in bed for cleaning their body or changing bed sheets, or when the head of the bed is elevated to improve ventilation or lung function or when a patient is put in Fowler's position for whatsoever reason. The latter would cause the body to gradually slide in the bed as gravity will pull the body downwards.

Prevention of PIs is the strategy accepted by the majority of health care organisations worldwide, and the efforts and resources allocated to prevention are constantly increasing, with the intent to focus on prevention and only treat the wounds that have formed despite the preventive approach. A successful preventive measure, which demonstrated exceptionally good outcomes in large‐scale, randomised clinical trials (RCTs), particularly in intensive care settings, is the use of prophylactic dressings 7, 8. These dressings are applied to protect certain regions of the body that are known to be prone to PIs and DTIs, particularly the sacrum and heels, on top of standard practice of prevention, that is, routine skin inspections, use of adequate support surfaces and repositioning protocols 1, 9, 10, 11.

Prophylactic dressings are, in fact, a spin‐off from dressings used for the treatment of wounds. The concept is still relatively new, and evidence for efficacy is rapidly being accumulated. Up‐to‐date evidence includes not only RCTs from multiple geographical sites, countries and health care cultures but also published complementary biomechanical research from our group, which explains mechanisms of action and connects them with the current understanding of the aetiology of PIs 12, 13, 14. Nevertheless, this preventive technology is in its early days, and there are substantial gaps in knowledge that need to be closed, a central one being: What is it in the design of a preventive dressing that needs to be different from the design of a dressing used for treating an existing wound? There is likely a list of such design features that would make future prophylactic dressings increasingly more efficient in providing protection to non‐injured tissues. However, it is already clear that such a potential design specification needs to target the minimisation of exposure to sustained tissue deformations, both at the skin and subdermally, and also successfully manage microclimate factors (moisture and wetness). The present study is focused on shedding new light on such a potential list of beneficial design features for a prophylactic dressing. In exploring this topic, we focus on the design of the Mepilex® Border Sacrum (MBS) dressing (Mölnlycke Health Care, Gothenburg, Sweden) given that the Mepilex® Border dressings are the only ones for which solid RCT data from large‐scale trials exist. These data confirm the efficacy of the Mepilex® Border dressings in the prevention of PI in clinical practice 7, and consistent with that, we have recently investigated the modes of action of these dressings 14 and have identified the multilayered structure and alternating stiffness composition of the materials of the dressing to be critical in these efficacy performances. However, some key design features for these dressings, such as the potential influence of a stiffness with a directional preference – that is, whether it is beneficial to produce a dressing that is more flexible and stretchable in its lateral directions (i.e., the cheeks of the buttocks) than in the longitudinal direction of the body (i.e., the spine) – have not been investigated. It is important then to examine the potential advantages of design features such as anisotropy (directional stiffness properties) of the dressing, which the MBS dressing exhibits, when tissue mechanics is altered and becomes abnormal, such as in the case of diabetes (or, to a lesser extent, with old age).

The objective of this study has been to expand our previous work regarding the modes of action and biomechanical efficacy of prophylactic dressings in protecting the soft tissues near the sacrum by specifically examining the role of anisotropy of the dressing while accounting for diabetic tissue conditions. For this purpose, a set of computational model variants of the three‐dimensional (3D) buttocks in the supine position was developed in order to represent patients with connective tissue changes associated with diabetes and how their tissues interact with either an isotropic or the anisotropic MBS dressing design. We applied loading that represents the bodyweight loads in real‐world scenarios, including the effect of external shear associated with gradual sliding in bed. Our present results add important new knowledge regarding the optimal design of a prophylactic dressing and how it is different from a design of a dressing aimed at treating an existing wound.

Methods

In this study, we developed six finite element (FE) model variants representing diabetic tissue conditions and used an additional six model variants of comparable healthy tissue cases obtained in our previous work 14 to investigate the potential effects of the stiffness anisotropy of prophylactic dressings on diabetic patients (Table 1). We systematically compared soft tissue exposures to elevated internal shear stresses and strain energy densities (SED) under the sacrum during supine weight bearing on a standard hospital mattress. We specifically compared the biomechanical effectiveness of prophylactic sacral dressings in alleviating tissue loads under the following conditions: (i) without a dressing (baseline), (ii) with an isotropic (hypothetical) multilayer sacral dressing and (iii) with the anisotropic Mepilex® Border Sacrum (MBS) dressing. We tested how well soft tissues around the sacrum are protected under the above conditions for pure compressive bodyweight loading (simulating horizontal bed rest) and also for a combined compression and shear loading mode (representing, e.g., 45° Fowler's position causing additional shear forces as the body tends to slide downwards in the bed). We tested the aforementioned effects of no dressing, isotropic dressing and MBS dressing on internal soft tissue load exposures for healthy versus diabetic tissue conditions, as detailed below.

Table 1.

Variants of the finite element modelling

| Model variant | Tissue properties | Dressing | Loading mode |

|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | Healthy* | Off | Compression |

| #2 | Healthy* | Off | Compression + shear |

| #3 | Healthy* | Multilayered, isotropic | Compression |

| #4 | Healthy* | Multilayered, isotropic | Compression + shear |

| #5 | Healthy* | MBS, anisotropic | Compression |

| #6 | Healthy | MBS, anisotropic | Compression + shear |

| #7 | Diabetic | Off | Compression |

| #8 | Diabetic | Off | Compression + shear |

| #9 | Diabetic | Multilayered, isotropic | Compression |

| #10 | Diabetic | Multilayered, isotropic | Compression + shear |

| #11 | Diabetic | MBS, anisotropic | Compression |

| #12 | Diabetic | MBS, anisotropic | Compression + shear |

Taken from Reference 14.

MBS, Mepilex® Border Sacrum.

Geometry

Development of the 3D anatomical model of the buttocks was accomplished in our previous published work 14 and is reported here briefly for completeness. We used 76 T1‐weighted axial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) slices of the weight‐bearing buttocks of a 28‐year‐old healthy female subject and used the ScanIP module of the Simpleware® software package to segment the pelvic bones, femurs, skeletal muscles, fat and skin tissues 15. Details regarding the specific MRI configuration, scan protocols and the medical ethical approval for these MRI studies are available elsewhere 14. In order to optimise the computational power that was available to us and, further, to achieve adequate numerical convergence of the modelling, we reduced the model volume to a 6·7 × 2 × 5·1 cm3 cube that captured the sacral bone and surrounding soft tissues, which is the relevant volume of interest (VOI) for this research application (Figure 1A). We further lumped the fat and skin tissues of the retro‐sacral region with an effective soft tissue component in the model variants. Specific considerations regarding these two simplifying assumptions are again available in our previous work 14.

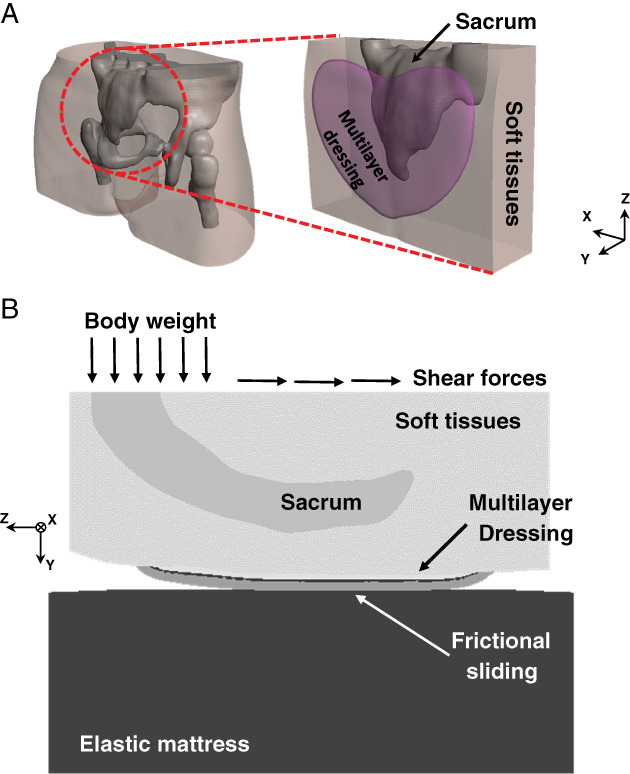

Figure 1.

Computational modelling to evaluate the efficacy of prophylactic sacral dressings: (A) finite element modelling of the buttocks with the Mepilex® Border Sacrum multilayer dressing during weight bearing (left), and a zoom‐in on the volume of interest (VOI) under the sacrum (right). (B) The applied loading conditions in a sagittal cross section through the sacrum.

Next, as in our previous modelling work 14, we introduced three of the layers of the MBS dressing, namely, the polyurethane foam (PUR), the non‐woven (NW) and the air‐laid (AL) layers, as physical layers in the modelling. We further considered the typical heart‐shaped geometry of the MBS dressing, again using the ScanIP module of Simpleware® (Figure 1A). We considered the innermost Safetac® skin contact layer as a tied interface between the soft tissue component and the PUR foam layer and the outermost backing film layer as frictional sliding between the AL layer and the mattress (Figure 1B), all as reported in previous papers from our group 12, 13, 14. A flat foam mattress under the soft tissues, or under the dressing in cases where a dressing was included, was added at the pre‐processing stage in PreView module of FEBio software suite (Ver. 1.19 PostView: University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, USA) (Figure 1B).

Mechanical properties of the tissues and dressing

Constitutive laws and mechanical properties of all tissue components and materials (dressing, mattress) were adopted from the literature. Specifically, the sacrum was assumed to be made of a linear‐elastic isotropic material with elastic modulus of 7 GPa and Poisson's ratio of 0·3 16, 17, 18. The soft tissues were assumed to be a nearly incompressible (Poisson's ratio of 0·49), non‐linear isotropic material, with their large deformation behaviour described by an uncoupled Neo‐Hookean model with the following SED function W:

| (1) |

where Gins (the instantaneous shear modulus) is 2 kPa 19, λi (i = 1, 2, 3) are the principal stretch ratios, K is the bulk modulus, and J = det(F) where F is the deformation gradient tensor. Specifically, we used the material constants reported by Oomens et al. 19 and calculated an effective soft tissue Gins, constituting of 60% skin and 40% fat, as in our previous modelling work of the buttocks 14. In cases where diabetic tissue conditions were simulated, we introduced a 40% increase in the soft tissue stiffness, namely, in Gins and in K 13. The layers of the (hypothetical) isotropic dressing were considered isotropic linear‐elastic materials with elastic moduli of 24, 150 and 30·6 kPa, based on measurements that were previously conducted in our laboratory 12, 13, 14, and Poisson's ratio of 0·258, based on published experimental data 20 (Table 2). The ‘backbone’ structure type, namely, stiffer longitudinal behaviour of the MBS dressing, was modelled, as before 14, using anisotropic mechanical properties for the layers of the dressing, specifically by a 45% increase of Gins and K only in the axial (Z) direction of the dressing (Figure 1B), based on measurements that were conducted in our laboratory to quantify this anisotropy (Table 2). The mattress was considered isotropic linear‐elastic as well, with an elastic modulus of 50 kPa and Poisson's ratio of 0·3, based on literature 12, 13, 21.

Table 2.

Mechanical properties of the model components: tissues, dressing and the mattress

| Model component | Shear elastic modulus (kPa) | Elastic modulus (kPa) | Poisson's ratio | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ex | Ey | Ez | ||||

| Soft tissues | Healthy | 2 | – | – | – | 0·49 |

| Diabetic | 2·8 | – | – | – | ||

| Sacrum | – | 7 × 106 | 7 × 106 | 7 × 106 | 0·3 | |

| Airlaid (Hypothetical Isotropic) | – | 30·6 | 30·6 | 30·6 | 0·258 | |

| Non‐woven (Hypothetical Isotropic) | 150 | 150 | 150 | 0·258 | ||

| Polyurethane foam (hypothetical isotropic) | 24 | 24 | 24 | 0·258 | ||

| Airlaid (anisotropic) | 30·6 | 30·6 | 44·3 | 0··258 | ||

| Non‐woven (anisotropic) | 150 | 150 | 217·5 | 0·258 | ||

| Polyurethane foam (anisotropic) | 24 | 24 | 34·8 | 0·258 | ||

| Mattress | 50 | 50 | 50 | 0·3 | ||

Body loads and shear and friction conditions

Boundary conditions were chosen to simulate the descent of the weight‐bearing sacrum during supine bed rest or 45° Fowler's position, without a dressing, with a (hypothetical) isotropic multilayer dressing or with the anisotropic MBS dressing. Downwards displacements in the range of 4·61–6·56 mm were applied on the top surface of the sacrum, in the reduced model volume, to reach a total reaction force of 40 N (roughly 7% of the total bodyweight of the subject). This same portion of the bodyweight load was transferred through the reduced model volume (Figure 1A) for all simulation cases for the purpose of consistent comparisons of outcome measures across the different model variants. In model variants where external shear was applied, we added horizontal displacements of the same magnitude in the axial (Z) direction of the model (Figure 1B) to account for the shearing forces that act on the sacral region when seated in 45° Fowler's position.

The bottom surface of the mattress was fixed for all motions; tied interfaces were defined at the bone‐soft tissue boundaries as well as between the soft tissues and the dressing, where relevant, to account for the adherence properties of the Safetac® (inner facing) layer of the MBS dressing. Frictional sliding was defined between the soft tissues or dressing, and the coefficients of friction with the mattress were set to 0·4 (bare skin) and 0·35 (backing film), respectively 12, 20.

Numerical methods

Meshing of the tissues and dressing components was performed using the ScanIP® module of Simpleware® 15, with denser meshes in the skin and dressing materials near the contact area with the mattress. Final meshes included a total of 139 964–212 585 linear tetrahedral elements describing the bones and soft tissues, as well as 1 636 013 linear tetrahedral elements describing the layers of the multilayer dressings. We note that these massive, non‐uniform numerical meshes and the consequent, large computer power were required for capturing the fine details of the structure of the dressings (in the scale of fractions of millimetres) – which function in our modelling and in real life in conjunction with the centimetre scale irregular structures of the buttocks. The flat mattress was meshed in PreView module of FEBio using 13 440 linear hexahedral elements. The FE simulations were all set up using the PreView module of FEBio (Ver. 1.19), analysed using the Pardiso linear solver of FEBio (http://mrl.sci.utah.edu/software/febio) (Ver. 2.5.0) and post‐processed using PostView of FEBio (Ver. 1.10.2) 22.

Biomechanical outcome measures

We systematically compared volumetric exposures of the soft tissues in the VOI, under the sacrum, to elevated shear stresses and SED values. The SED data were pooled from all the soft tissue elements that were located immediately below the sacrum (Figure 1B). Converging time steps were chosen for data collection so that the total vertical reaction force acting back from the mattress was within less than a 3% difference from the target reaction force (40 N).

Results

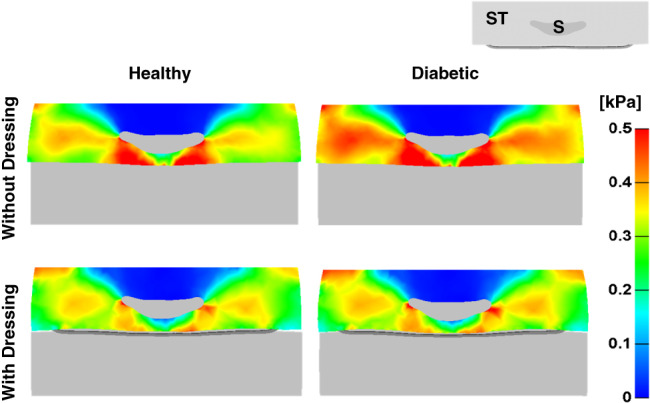

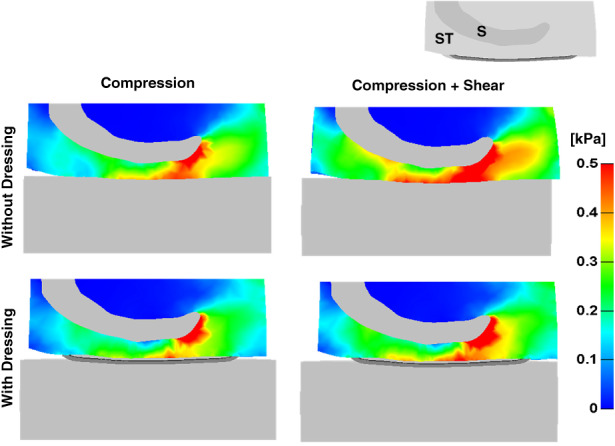

Maximal shear stress distributions in the soft tissues of the retro‐sacral region for healthy and diabetic tissue conditions, with or without the anisotropic MBS dressing and under combined compression and shear loads are shown in Figure 2. In agreement with our previous work regarding prophylactic sacral dressings 14, peak shear stresses were found immediately under the lateral aspects and tip of the sacrum (Figures 2 and 3). While diabetic tissue conditions resulted in slightly elevated shear stresses when external shear was applied in addition to the vertical compression, the anisotropic MBS dressing reduced peak stresses considerably in both healthy and diabetic cases. Specifically, the peak stress in healthy and diabetic tissues was reduced by approximately 24% and 27·5%, respectively, when using the MBS dressing in the case of combined compression and shear loading. As expected, the added external shear, simulating a patient who is lying in Fowler's position and begins to slide down in bed (or during repositioning), resulted in increased exposure of the soft tissues surrounding the scrum to elevated shear stresses, either with the use of the anisotropic MBS dressing or without it (Figure 3). Nevertheless, the anisotropic MBS dressing, which is stiffer in the Z‐direction along the sacrum, was again able to consistently and considerably reduce peak shear stresses in the deep tissues of the retro‐sacral region, with a more pronounced effect when external shear was applied in that same direction (Figure 3). Specifically, the peak stress in the case of compression only was reduced by 14%, whereas in the case of combined (compression plus shear) loading, the effect of the MBS dressing was much more prominent, with a reduction of 27·5% in peak stress.

Figure 2.

Maximal shear stresses in the soft tissues (ST) of the buttocks in an axial cross section through the sacrum (S), without a dressing (top) and with the anisotropic Mepilex® Border Sacrum multilayer dressing (bottom), under combined compression and shear loading and in healthy (left) versus diabetic (right) tissue conditions.

Figure 3.

Maximal shear stresses in the soft tissues (ST) of the buttocks, in a coronal cross section through the sacrum (S), without a dressing (top) and with the anisotropic Mepilex® Border Sacrum multilayer dressing (bottom), under pure compression loading (left) and combined compression and shear loasing (right), with diabetic tissue conditions.

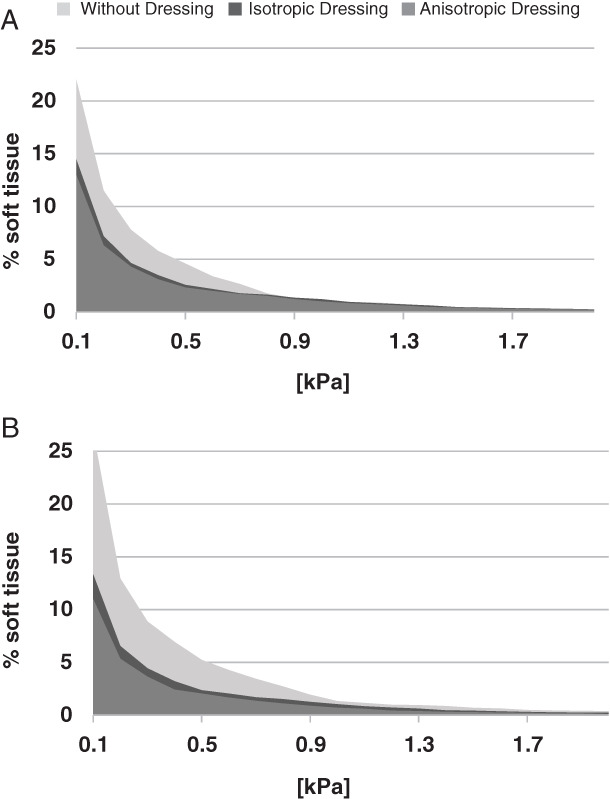

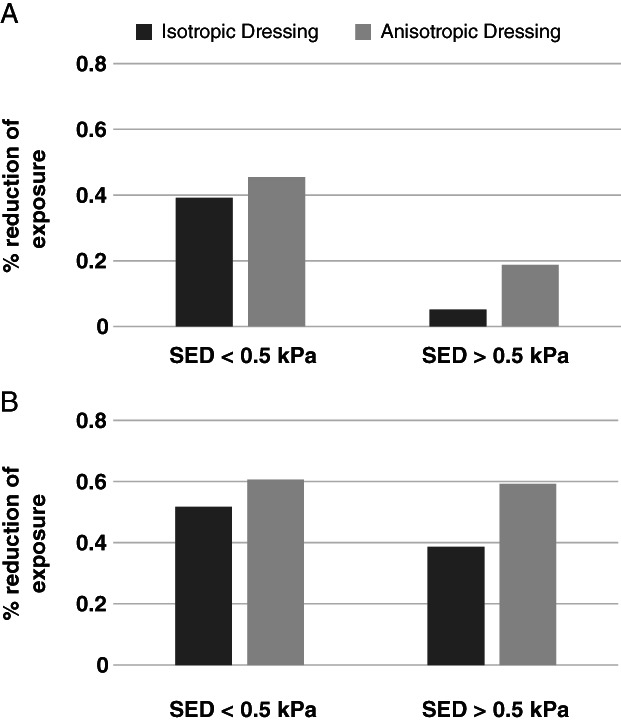

Cumulative volumetric exposures of diabetic soft tissues under the sacrum to increasing values of SED, when either pure compression or combined compression and shear were applied, without a dressing, with a hypothetical isotropic multilayer dressing and with the anisotropic MBS dressing, are shown in Figure 4. Interestingly, while in healthy tissue cases and when only vertical compression was applied, we did not see a meaningful advantage of the anisotropy feature of the MBS dressing – in terms of reduction of internal tissue exposures to elevated SED values 14, in the case of diabetic tissues, the advantage in anisotropy was clearly evident for the two loading modes. Specifically, under pure compression, the hypothetical isotropic multilayer dressing lowered the volumetric exposure of the soft tissues surrounding the sacrum by 39% and 5%, in the low (<0·5 kPa) and high (>0·5 kPa) SED domains, respectively. The corresponding values for the anisotropic MBS dressing were 45% and 18% (Figure 5A), which is a notable contribution of the anisotropic design feature (per se) to deep tissue protection. This tissue protective effect of the anisotropy of the MBS dressing was even more remarkable when additional external shear was introduced: The hypothetical isotropic multilayer dressing yielded 52% and 39% reductions in tissues exposure in the low and high SED domains, respectively, whereas the anisotropic MBS dressing reduced tissue exposures by as much as 60% in both domains (Figure 5B), which again highlights the importance of the anisotropic MBS design. Hence, the added value that the anisotropy of the MBS dressing provides, in reducing the exposure of soft tissues to elevated SED levels, is particularly beneficial for diabetic patients who experience the increase in connective tissue stiffness that is characteristic to this population.

Figure 4.

Cumulative volumetric exposures of the soft tissues under the sacrum to strain energy density (SED) in pure compression mode (A) and under combined compression and shear loads (B), with diabetic tissue conditions.

Figure 5.

Percentage of reduction in soft tissue exposures to strain energy density (SED), with the isotropic (theoretical) multilayer dressing and the anisotropic Mepilex® Border Sacrum multilayer dressing, with respect to the no‐dressing case, under pure compression loading (A) and combined compression and shear loading (B), with diabetic tissue conditions.

Discussion

This study, which builds on our previous published work with regards to the biomechanical function of prophylactic dressings in PI prevention and DTI prevention in particular, employed multiple MRI‐based 3D FE model variants of the buttocks in a supine position in order to systematically study the efficacy of these preventive dressings. Focusing here, as a follow‐up study to our previous article 14 on the stiffness and anisotropy properties of the MBS sacral dressing, we compared the biomechanical efficacy of MBS in alleviating tissue deformations and stresses where diabetic tissue conditions exist, with respect to a healthy tissue status. We further examined whether there is an additional protective effect provided by the anisotropy associated with the structural design of the MBS dressing by comparing it to an isotropic (hypothetical) multilayer dressing of the same size and shape.

Consistent with our previous work 14, we found here that the MBS dressing is effective in reducing the exposure to sustained tissue deformations and stresses for both healthy and diabetic tissue conditions and under either compression loading or compression combined with shear. We attribute this observed reduction in volumetric exposure and peak load values (Figures 2, 3, 4) to the unique structure of the MBS multilayered dressing, which diverts deformations and loads from the tissues around the sacrum to the deformable structure of the dressing itself, particularly with regards to the shear deformations. This unique effect that is facilitated by the multilayered structure and material composition of the MBS dressing is added to the direct local cushioning effect of this dressing, which spreads pressures under the sacral region of the weight‐bearing buttocks.

The results of the present study not only correlate with our prior work 14 but also add an important insight regarding prophylactic dressings, which has not been reported before; that is, our data emphasise the advantage of the anisotropy feature of the MBS prophylactic dressing. Specifically, we demonstrated here that the MBS prophylactic dressing was able to reduce the volumetric exposure of the soft tissues surrounding the sacrum to deformations, as well as to reduce the high peak stresses, particularly in the case of diabetic tissue conditions under combined compression and external shear loading. The combined compression and shear loading of the buttocks represents a realistic and very common real‐life scenario where hospitalised supine patients are frequently repositioned or gradually slide in their bed, for example, in Fowler's position. For (the stiffer) diabetic tissue conditions, we found that external shear loads caused an elevation in shear stress in subdermal tissues (Figure 2). The anisotropy properties of the MBS dressing makes it stiffer in the Z‐direction (the longitudinal direction of the dressing, i.e., the direction of the spine), which is also the direction of potential downward sliding of the body due to gravity, especially if the head of the bed is elevated. As the MBS dressing is stiffer along the line of the spine, which is the direction where external shear loads would typically apply, the dressing will act to preserve tissue shape and minimise tissue distortions in that longitudinal direction. This explains how the MBS dressing is able to reduce the exposure to tissue deformations further than an isotropic dressing, and hence, anisotropy in a prophylactic dressing with stiffness along the spine provides extra protection against PIs and DTIs. Another important feature of the MBS dressing in this regard is the contribution of the low‐friction backing film layer, which reduces frictional forces at the interface of the body. This adds to protecting the tissues from distortions in shear along the gravity‐caused sliding direction. In particular, the MBS dressing was found to be highly beneficial in protecting diabetic (connective) tissues, which tend to be stiffer and hence experience greater shear stresses than non‐diabetic tissues.

Although this study clearly demonstrates that a multilayer prophylactic sacral dressing is effective in alleviating sustained tissue deformations and stresses in either healthy or diabetic tissues, there are assumptions and limitations in our modelling (as in any modelling work), which should be discussed here. First, the anatomy that we have used is of an individual and does not necessarily represent all possible anatomical variations, particularly with respect to bony or malnourished patients as well as the obese. Moreover, for practical purposes, we considered homogeneous connective tissue stiffening in diabetes, although it is suspected that the alternations in tissue stiffness properties that are associated with this disease are hardly homogeneous. These assumptions are additional to those that have been made in our previous work and that are reported there 14. With that being said, for the purpose of modelling the efficacy of prophylactic dressings, the influence of their possible design features on tissue loads and the potential contributions of such design variants to PI prevention, we feel that these assumptions are all reasonable and facilitate systematic, standard and objective quantitative comparisons for the computer‐aided design of existing and future dressings.

To conclude, in this study, we found that multilayered prophylactic sacral dressings are remarkably effective in reducing the exposure to sustained soft tissue deformations and stresses near the sacrum, particularly in diabetic tissues that tend to be stiffer than non‐diabetic. Moreover, we found that the anisotropic design of the MBS dressing is advantageous in providing extra protection to the skin and subdermal tissues around the sacrum from PIs and DTIs, especially in the very common scenario of external shear loads applied to the sacrum, which are caused by the gravity pulling the body downwards in the bed. Our present study therefore provides additional important insights regarding the optimal design of prophylactic dressings, which, in turn, informs clinicians and decision‐makers regarding beneficial features that they need to inquire upon before selecting the type of prophylactic dressing to be used in their facility.

References

- 1. National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel and Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance. In: Haesler E, editor. Prevention and Treatment of Pressure Ulcers: Quick Reference Guide. Perth, Australia: Cambridge Media; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Van Gilder C, Macfarlane GD, Meyer S. Results of nine international pressure ulcer prevalence surveys: 1989 to 2005. Ostomy Wound Manage 2008;54:40–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Vanderwee K, Clark M, Dealey C, Gunningberg L, Defloor T. Pressure ulcer prevalence in Europe: a pilot study. J Eval Clin Pract 2007;13:227–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Connizzo BK, Bhatt PR, Liechty KW, Soslowsky LJ. Diabetes alters mechanical properties and collagen fiber realignment in multiple mouse tendons. Ann Biomed Eng 2014;42:1880–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Andreassen TT, Seyer‐Hansen K, Oxlund HB. Biomechanical changes in connective tissues induced by experimental diabetes. Acta Endocrinol 1981;98:432–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Goodfield MJD, Millard LG. The skin in diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 1988;31:567–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Santamaria N, Gerdtz M, Sage S, McCann J, Freeman A, Vassilou T, DeVincentis S, Wei A, Manias E, Liu W, Knott J. A randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of soft silicone foam multi‐layer dressings in the prevention of sacral and heel pressure ulcers in trauma and critically ill patients: the border trial. Int Wound J 2015;12:302–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Santamaria N, Gerdtz M, Liu W, Rakis S, Sage S, Ng AW, Tudor H, McCann J, Vassiliou T, Morrow F, Smith K, Knott J, Liew D. Clinical effectiveness of a silicone foam dressing for the prevention of heel pressure ulcers in critically ill patients: border II Trial. J Wound Care 2015;24:340–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fowler E, Scott‐Williams S, McGuire JB. Practice recommendations for preventing heel pressure ulcers. Ostomy Wound Manage 2008;54:42–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Duncan KD. Preventing pressure ulcers: the goal is zero. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2007;33:605–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McInnes E, Jammali‐Blasi A, Bell‐Syer SEM, Dumville JC, Cullum N. Support surfaces for pressure ulcer prevention. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011, Paper no. CD001735. https://doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001735.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Levy A, Frank BM, Gefen A. The biomechanical efficacy of dressings in preventing heel ulcers. J Tissue Viability 2015;24:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Levy A, Gefen A. Computer modeling studies to assess whether a prophylactic dressing reduces the risk for deep tissue injury in the heels of supine patients with diabetes. Ostomy Wound Manage 2016;62:42–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Levy A, Gefen A. What makes a sacral prophylactic dressing effective: the combined protective outcome of a multi layered structure with stiffness anisotropy. In press.

- 15. Simpleware® Ltd . ScanIP, +FE, +NURBS and + CAD reference guide version 5.1. Salt Lake City, UT, USA: University of Utah, 2012. URL http://www.simpleware.com/software/. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Linder‐Ganz E, Shabshin N, Itzchak Y, Gefen A. Assessment of mechanical conditions in sub‐dermal tissues during sitting: a combined experimental‐MRI and finite element approach. J Biomech 2007;40:1443–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Palevski A, Glaich I, Portnoy S, Linder‐Ganz E, Gefen A. Stress relaxation of porcine gluteus muscle subjected to sudden transverse deformation as related to pressure sore modeling. J Biomech Eng 2006;128:782–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gefen A, Haberman E. Viscoelastic properties of ovine adipose tissue covering the gluteus muscles. J Biomech Eng 2007;129:924–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Oomens CW, Zenhorst W, Broek M, Hemmes B, Poeze M, Brink PR, Bader DL. A numerical study to analyse the risk for pressure ulcer development on a spine board. Clin Biomech 2013;28:736–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Call E, Pedersen J, Bill B, Black J, Alves P, Brindle CT. Enhancing pressure ulcer prevention using wound dressings: what are the modes of action? Int Wound J 2015;12:408–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sopher R, Nixon J, McGinnis E, Gefen A. The influence of foot posture, support stiffness, heel pad loading and tissue mechanical properties on biomechanical factors associated with a risk of heel ulceration. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater 2011;4:572–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Maas SA, Ellis BJ, Ateshian GA, Weiss JA. FEBio: finite elements for biomechanics. J Biomech Eng 2012;134:5–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]