Abstract

Skin tears are an increasingly common injury occurring in the elderly population and have significant associated morbidity secondary to poor wound healing, prolonged hospital stays and reduced mobility. There has been a shift in practice for the acute management of skin tears within our institution, which has resulted in improved outcomes and reduced morbidity for this common and debilitating injury. Review of past and current practices including cost analyses has led to the establishment of a management protocol for the hospital and wider area health service with the aim to reduce the burden of disease amongst our ever‐expanding elderly population.

Keywords: Skin grafting, Skin tear management, Wound care

Introduction

Skin tears are an increasingly common problem facing busy emergency departments. They are associated with significant morbidity amongst the elderly population, in which they are most frequent 1, 2, 3, 4.

Skin tears result from traumatic separation of the epidermis and dermis following friction and/or shearing forces, together with intrinsic skin changes associated with aging 5. They are highly variable in nature, and timely assessment of the extent and depth of trauma, presence of haematoma and any degree of tissue necrosis assist appropriate management and/or referral to a Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery unit.

The aims of skin tear management reflect those of general wound management: to reduce the risk of infection, promote healing and obtain optimal cosmetic and functional outcomes. Few classification systems have been proposed to provide guidance to skin tear management, and there exists little evidence to guide best practice in the elderly.

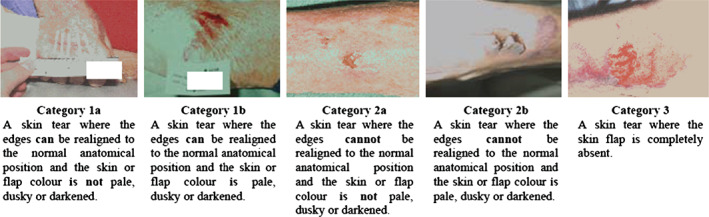

The Payne–Martin Classification System for Skin Tears was devised following a pilot study in 1985 and refined in 1993 6, 7. The three categories and five types of skin tears were based on morphological characteristics of the presenting epidermal injury. Australian literature confirms a lack of use of the Payne–Martin classification system 8, leading to the establishment of the Skin Tear Audit Research (STAR) Project in 2007 9. The STAR Classification System was subsequently described and tested and is used within our unit (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

STAR Classification System.

Skin tears of Category 2a and above generally necessitate specialist referral. They are, however, often managed using the traditional conservative approach of irrigation, approximation of the skin flap edges, application of adhesive strips and/or non‐adherent dressings and review of the wound at days 3–7. The management of skin tears with greater tissue loss (i.e. Category 3) or those failing conservative measures usually involves surgical debridement and grafting. This is not without risk in the elderly population due to factors such as prolonged fasting, general anaesthesia, donor site morbidity, prolonged hospital stay and reduced mobility.

There has been a change in practice at the Royal North Shore Hospital (RNSH; Sydney, Australia) where a trained member of the Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery team performs timely debridement and grafting of appropriately referred skin tears within the emergency department. Patients with skin tears presenting to any hospital within the area health service are treated as a medical emergency and those assessed as Category 2a and above are referred immediately to the Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery team at RNSH.

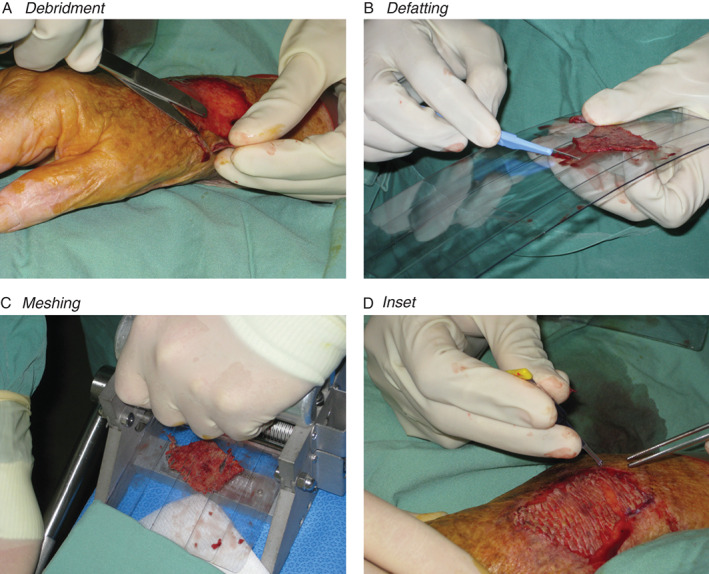

Category 2a and 2b skin tears are generally treated under local anaesthesia and sterile conditions within the emergency department as demonstrated in Figure 2A–D. The wounds are irrigated and debrided; the viable skin flap is excised, defatted and meshed on a skin board using a skin graft mesher; and the meshed skin relaid as a graft to the clean wound bed. The graft is secured with tissue glue and/or sutures and a non‐stick dressing applied.

Figure 2.

Category 2a and 2b skin tears treated under local anaesthesia and sterile conditions within the emergency department. (A) Debridement. (B) Defatting. (C) Meshing. (D) Inset.

The application of negative pressure wound therapy or compression bandages is individualised to the patient and presenting injury. The patient is discharged from the emergency department (unless further investigation or medical admission indicated) and reviewed in a specialty dressings clinic 5–7 days following injury/grafting. Ongoing review is dependent on wound healing and patient circumstances, with many patients discharged to the community for simple dressings following the initial graft review. Indications for operative management under general anaesthesia remain unchanged, with more severe skin tears requiring patient admission and treatment in the operating theatre.

This project aims to review the change in management of skin tears at RNSH. A protocol for dissemination to the Local Health District (LHD) to improve outcomes and reduce costs associated with skin tears in the elderly is proposed.

Methods

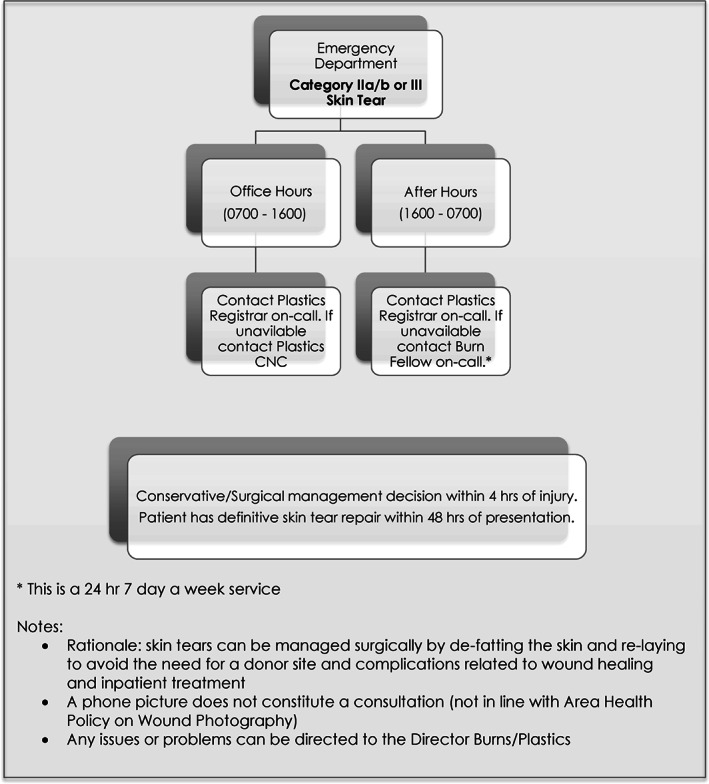

A referral flowchart (Figure 3) was devised and disseminated to the emergency departments within the LHD, including those of five peripheral hospitals. Following discussions with the RNSH Plastics Registrar, appropriate patients are transferred to RNSH for assessment and management.

Figure 3.

Emergency department referral flowchart.

Following review at RNSH, a decision regarding conservative/surgical management is made. Skin tears deemed appropriate for management within the emergency department are treated using the method described and demonstrated in Figure 2. All patients are assessed after procedure by a member of the Occupational Therapy team and discharged if deemed safe and not requiring further investigation or treatment related to their presentation or comorbidities. Patients with skin tears requiring treatment in the operating theatre are admitted subject to emergency theatre availability, after obtaining consent and fasting.

Data were collected prospectively for patients treated using the new referral and management system over a 6‐month period. Data collected included age, injured site, use of NWPT, length of inpatient stay, days to heal, relevant medical history and complications.

For comparison, a medical record review was performed for all patients admitted to RNSH for the management of skin tears over a 6‐month period prior to introduction of the pilot referral/management protocol. Data collected in addition to that described for the study group included days to donor site healing and related complications.

Cost analyses were performed using the New South Wales Health Diagnosis‐Related Group (DRG) Classification based on patients with 1–2% skin tears on the upper arm or lower leg, requiring graft/donor site creation and one bed day on a short‐stay ward.

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by The Northern Sydney Coast (EC0012) Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC).

Results

Thirty‐six patients were referred and managed using the pilot protocol over a 6‐month period. Medical records of 35 patients treated within the department in the prior 6 months were reviewed. Table 1 compares the two groups. There was a significant reduction in days to heal (17 to 11), length of inpatient stay (12·2 to 1·5 days) and total bed days (426 to 56) following implementation of the new referral and management protocol. The average time for donor site healing in those undergoing grafting in the operating theatre was 14·5 days.

Table 1.

Comparison of skin tear management approaches

| Past management | New protocol | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 35 | 36 |

| Age | ||

| Average | 86 | 85 |

| Range | 52–104 | 72–103 |

| Average time to heal (days) | 17 | 11 |

| Inpatient stay (days) | ||

| Average | 12·2 | 1·5 |

| Range | 3–26 | 0–10 |

| Total bed days | 426 | 56 |

The estimated cost of donor site dressings per patient is $166·79 (uncomplicated) to $456·81 (complicated/delayed healing). The estimated cost of surgery (grafting) and hospitalisation (one bed day) is $1422·48. Therefore, the minimal cost saving for early management of appropriate skin tears within the emergency department is $1588·29 ($166·79 + $1422·48) without donor site complications to $1879·29 ($456·81 + $1422·48) with donor site complications. The cost saving would evidently increase (per bed day) with extended postoperative hospital stays.

Case examples

The following case examples demonstrate the acute management and subsequent outcome of skin tear injuries treated using the new protocol.

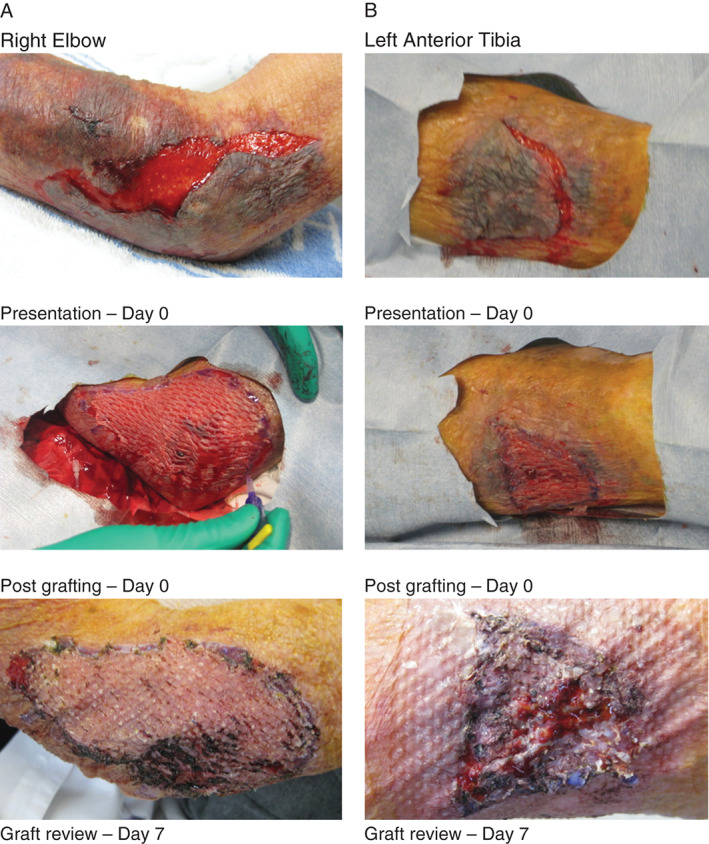

Patient 1 (Figure 4) is a 92‐year‐old nursing home resident referred by the emergency department with Category 2b skin tears to her right elbow and left pre‐tibial regions. Debridement, defatting, meshing and ‘grafting’ of the injured skin was performed in the emergency department. She was discharged back to her nursing home within 8 hours of presentation and returned for a single graft review at day 7. She was discharged to the community with simple dressings at this review.

Figure 4.

Category 2b skin tears on the (A) right elbow and (B) left anterior tibia.

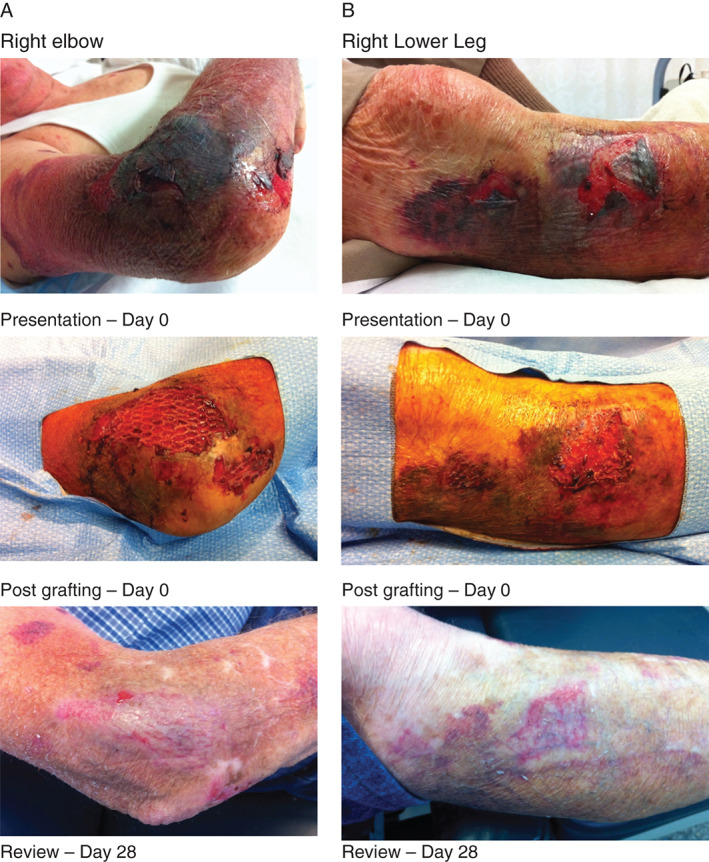

Patient 2 (Figure 5) is a 76‐year‐old independent male who sustained Category 2b right elbow and pre‐tibial skin tears following a mechanical fall on his driveway. Debridement, meshing and grafting of the injured skin was performed within the emergency department and he was discharged the same day following cardiology review. He was reviewed in clinic 4 weeks after injury/treatment.

Figure 5.

Category 2b skin tears on the (A) right elbow and (B) right lower leg following a mechanical fall.

Discussion

The new referral system and acute management approach to skin tear injuries piloted at RNSH has led to reduced inpatient stays and associated complications in the elderly population.

The change in practice within our unit has been accompanied by a number of recognised advantages:

Emphasis on the treatment of skin tears as ‘medical emergencies’ – ensures timely assessment and/or referral of injuries.

Early specialist review – aids acute management of wounds and optimises healing.

Technique of ‘grafting’ rather than skin approximation with adhesive strips/dressings – allows thorough debridement/irrigation and optimises healing.

Improved wound healing – reduces limitations on mobility and encourages faster return to activities of daily living.

Avoidance of prolonged fasting times due to theatre delay/cancellation – reduces complications associated with fasting in the elderly.

Avoidance of donor site morbidity – reduces morbidity and complications in a population with intrinsically poor healing.

Reduction in hospital admissions and inpatient stays – reduces inpatient complications and financial burden to the surgical unit.

The emergency department referral flowchart piloted in this study will be disseminated throughout the LHD to promote the changes in practice for the management of skin tear injuries. Initial cost savings will likely be consumed by dissemination of the new protocol, education and purchase of additional equipment required to meet the demand of increased referrals. However, long‐term financial benefit will accompany the reduced burden of disease within the community.

It is envisaged that additional staff will be trained in the technique described to benefit a broader spectrum of the community. This may extend to appropriately trained nurse practitioners and senior clinical nursing staff who work in key areas such as emergency departments and outpatient clinics.

Skin tears are a significant burden of disease on our ever‐expanding elderly population. These injuries should be treated as medical emergencies and appropriately referred to a Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery unit for acute management within the emergency department if appropriate.

References

- 1. Penzer R, Finch M. Promoting healthy skin in older people. Learn Disabil Pract 2001;4:33–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nazarko L. Maintaining the condition of ageing skin. Nurs Resident Care 2007;9:160–3. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Reddy M. Skin and wound care: important considerations in the older adult. Adv Skin Wound Care 2008;21:424–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ratliff C, Fletcher KR. Skin tears: a review of the evidence to support prevention and treatment. Ostomy Wound Manage 2007;53:32–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Battersby L. Exploring best practice in the management of skin tears in older people. Nurs Times 2009;105:16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Payne R, Martin ML. Defining and classifying skin tears: need for a common language. Ostomy Wound Manage 1993;39:16–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Payne R, Martin M. The epidemiology and management of skin tears in the older adult. Ostomy Wound Manage 1990;26:26–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. White W. Skin tears: a descriptive study of the opinions, clinical practice and knowledge base of RNs caring for the aged in high care residential facilities. Prim Intent 2001;9:138–49. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Carville K, Lewin G, Newall N, Haslehurst P, Michael R, Santamaria N, Roberts P. STAR: a consensus for skin tear classification. Prim Intent 2007;15:18–28. [Google Scholar]