Abstract

Venous leg ulcers (VLUs) have higher tumor necrosis factor‐α (TNF‐α) levels compared with normal skin. Refractory VLUs of long duration have higher TNF‐α levels compared with VLUs of shorter duration. As up to 75% of VLUs fail to heal with standard care, we sought to evaluate the role of anti‐TNF‐α therapy for patients with refractory VLUs. Evaluable data were obtained in four of five subjects with recalcitrant VLUs treated with 80 mg of subcutaneous adalimumab at week 0 and with 40 mg at week 2 along with compression therapy and were followed‐up for 6 weeks. Wound biopsies taken at weeks 0 and 4 were stained with anti‐TNF‐α antibodies. Average 4‐week percent wound size reduction was 20.5% ± 6.4%. Two patients had wound size reduction more than 25%, and their percent wound size reduction correlated to percent TNF‐α staining score reductions (P = 0.02, R2 = 0.999). VLU TNF‐α level decrease 4 weeks post‐adalimumab treatment correlated with wound healing.

Keywords: Adalimumab, Chronic wound, Immunohistochemistry, TNF‐alpha, Venous leg ulcer

Introduction

Venous leg ulcers (VLUs) cause up to 90% of lower extremity chronic cutaneous ulcers 1. It is estimated that VLUs cost $14·9 billion annually and, depending on wound size and duration, up to 75% of patients with VLUs fail to heal within 24 weeks of standard compression therapy 2, 3. Therefore, a better understanding of patients who fail to heal with compression therapy is needed. Aberrant cytokine expression may be involved in VLU pathogenesis 4; specifically, increased tumor necrosis factor‐α (TNF‐α) levels both systemically and in ulcer tissue have been associated with venous ulceration 5, 6. TNF‐α cell‐signaling protein expression is increased with greater expression of matrix metalloproteinases, interleukins 1 and 6 and inflammatory cell adhesion molecules such as Intercellular Adhesion Molecule‐1 (ICAM‐1), which cause increased proteolysis and inflammation, resulting in delayed healing 5. TNF‐α decreases expression of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases and growth factors such as tumor growth factor‐beta (TGF‐β), which affects collagen production and may impair healing 5. Previously we found elevated levels of TNF‐α in VLUs compared with normal skin as well as in VLUs of longer duration compared with VLUs of shorter duration 5, 7. Moreover, patients with a gene polymorphism associated with elevated TNF‐α production, TNFA‐308A allele, are at twice the risk of venous ulceration 8, 9. Therefore, TNF‐α is a potential wound‐healing target. In vitro anti‐TNF‐α agents such as infliximab, etanercept and adalimumab increase wound collagen, decrease inflammatory cytokines and circulating leukocytes, decrease fibroblast apoptosis and TNF‐α binding 5. In one case series, topical infliximab promoted wound healing of various chronic wounds 10; however, tissue TNF‐α levels were not measured.

Adalimumab is a fully human recombinant IgG1 monoclonal antibody against TNF‐α, which is Food and Drug Administration (FDA)‐approved for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriasis, ulcerative colitis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis and Crohn's disease 11. We sought to investigate the use of subcutaneous adalimumab for the treatment of recalcitrant VLUs and to evaluate whether wound tissue TNF‐α level reduction would be associated with improved healing.

Materials and methods

After institutional review board approval, subjects with recalcitrant VLUs were enrolled. Refractory VLUs were defined as ulcers present on the lower leg for greater than 6 months with an area greater than 5 cm2 with two of the following: varicosities, venous dermatitis, atrophie blanche, hyperpigmentation or lipodermatosclerosis 12. We excluded patients with moderate to severe arterial insufficiency [ankle brachial index (ABI) < 0·65], wound infection, cellulitis, osteomyelitis or who were treated with antibiotics within 2 weeks, or subjects who received bioengineered skin or topical growth factors within 6 weeks. We also excluded subjects with a history of tuberculosis, lymphoma, heart failure, demyelinating diseases, neurological disease or previous treatment with anti‐TNF‐α therapy, positive purified protein derivative test, positive hepatitis B panel, positive pregnancy test or liver enzymes greater than two times the upper limit of normal.

At enrollment (week 0) after a 1‐week screening period, incisional biopsies were taken from the wound margin, and subjects received 80 mg subcutaneous adalimumab and standard wound care with multi‐layer compression. Patients were followed‐up weekly with wound photography, planimetry, symptom assessments and standard wound care with compression. At week 2, subjects received one 40 mg subcutaneous injection of adalimumab. At week 4, incisional biopsies were taken from the wound margin. Subjects were followed‐up for 2 more weeks (total of 6 weeks excluding screening week).

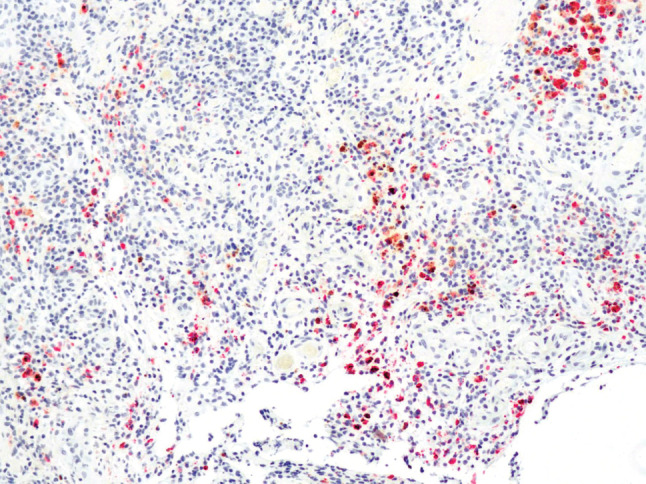

Tissue was fixed with formalin and processed according to standard histological protocols. Immunohistochemistry was performed on the samples to stain for TNF‐α utilizing monoclonal anti‐TNF‐α antibodies (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) at a 1:500 dilution in a Bond‐Max automated staining instrument using polymeric horseradish peroxidase (HRP Polymer) (Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL). Sections were contrasted with Fast Red chromogen (Leica Biosystems, Buffalo Grove, IL). Dermatopathologists blinded to clinical information made qualitative and quantitative assessments of TNF‐α staining. Intensity of cytoplasmic TNF‐α staining was graded on a 0 (no staining) to 3 (maximal intensity staining) scale 7. The number of positive staining cells per representative high‐powered field was scored from 0 to 4 (0 = 0 cells, 1 = 1–30 cells, 2 = 31–60 cells; 3 = 61–90 cells; 4 = >90 cells). An overall score was calculated for each VLU by multiplying the intensity value with the number of positive cells value. We performed a linear regression model to relate 4‐week percent wound reduction to 4‐week percent TNF‐α score reduction.

Results

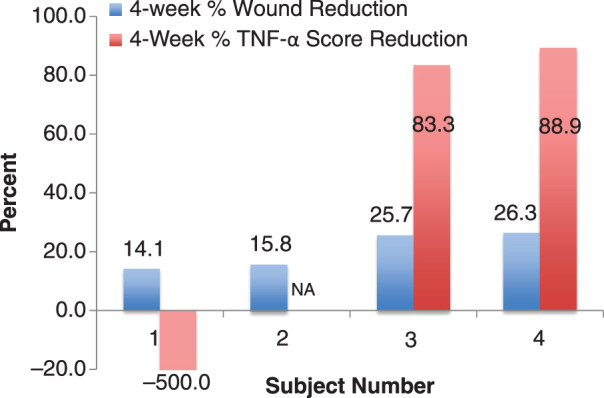

Four of five subjects had evaluable histological data–including two women and two men with an average age of 50·2 ± 15·5 years and an average initial ulcer size of 12·08 cm2 ± 6·3 cm2 (Table 1). All patients tolerated the treatments without complaints, adverse reactions or increase in wound size. Average 4‐week percent wound size reduction was 20·5% ± 6·4%. The two subjects with percent wound size reductions greater than 25% demonstrated positively correlated percent score reduction (Figure 1), while the TNF‐α score of subjects with 4‐week percent wound reduction less than 16% did not improve. Unpaired two‐tailed t‐test P value of mean initial ulcer size and age of subjects 1 and 2 versus subjects 3 and 4 were 0·24 and 0·46, respectively. Linear regression of 4‐week percent wound size reduction and 4‐week percent staining score reduction demonstrated a significantly positive correlation (P = 0·02, R 2 = 0·999). Subject 2 could not be included in this analysis, as he did not have a positive initial TNF‐α staining (score of 0). Representative tissue TNF‐α immunostaining is shown in Figure 2.

Table 1.

Patient demographics, percent wound size reduction and percent tumor necrosis factor‐alpha (TNF‐α) staining score reduction at 4 weeks

| Subject | Age | Gender | Ulcer location | Ulcer size (plan), cm2, week 0 | TNF‐α staining score, week 0 | Ulcer size, cm2, week 4 | TNF‐α staining score, week 4 | Four‐week percent wound reduction | Four‐weeek TNF‐α percent staining score reduction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 70 | Female | Right medial malleolus | 6·4 | 1 | 5·5 | 6 | 14·06 | −500% |

| 2 | 45 | Male | Posterior right leg | 9·5 | 0 | 8 | 2 | 15·79 | NA |

| 3 | 33 | Female | Anterior left leg | 21 | 12 | 15·6 | 2 | 25·71 | 83% |

| 4 | 53 | Male | Anterior right leg | 11·4 | 9 | 8·4 | 1 | 26·32 | 89% |

Figure 1.

Four‐week percent wound reduction and percent tumor necrosis factor‐alpha (TNF‐α) score reduction.

Figure 2.

Representative anti‐tumor necrosis factor‐alpha (anti‐TNF‐α) immunostaining of a venous leg ulcer (VLU). Pre‐adalimumab treated VLU biopsy stained with anti‐TNF‐α antibody. Positive cells are orange to bright red/pink (100×).

Discussion

In this first pilot clinical trial involving four patients with recalcitrant VLUs, all four patients treated with subcutaneous adalimumab, experienced measureable 4‐week percent wound reductions. We found 4‐week percent wound size reductions greater than 25% significantly correlated with percent change in histologically measured wound TNF‐α levels. We did not note adverse reactions, or wound deterioration in 6 weeks of follow‐up. It is possible that in a larger study, a greater patient response to subcutaneous adalimumab may be observed.

While two subjects experienced a decrease in TNF‐α score, two subjects who did not improve significantly clinically did not show decreased TNF‐α (rather an increase in TNF‐α scores) post‐adalimumab treatment, suggesting either a TNF‐α independent mechanism for poor healing or differential response to anti‐TNF‐α treatment. The two groups' average age and initial wound sizes were not significantly different. Biopsies were taken 4 weeks post‐treatment, which should be a reasonable amount of time to have seen a correlated change in TNF‐α score, for in a prior study of psoriasis patients treated with infliximab (another anti‐TNF‐α biological agent), investigators demonstrated significant tissue TNF‐α score reductions at 2 and 12 weeks post‐treatment 13. We did not measure tissue adalimumab concentrations, and perhaps subjects who did not respond to adalimumab based on staining score and wound size reduction exhibited lower tissue drug concentrations.

This pilot study is limited in that we enrolled only four patients and the length of the trial, 6 weeks total follow‐up, is relatively short. Future research involving a longer, larger trial with increased longitudinal TNF‐α and other cytokine wound level measurements and adalimumab injections may produce more significant correlations between tissue TNF‐α levels, healing and adalimumab treatment.

In summary, four subjects with recalcitrant VLUs were treated with subcutaneous adalimumab along with compression therapy. Overall, a 4‐week wound size reduction was noted, and in patients with percent 4‐week wound size reduction greater than 25%, this positively correlated with percent TNF‐α staining score reduction. This pilot study indicates that future larger trials of adalimumab are viable and may further elucidate the efficacy of this therapy for recalcitrant VLUs with simultaneous monitoring of wound TNF‐α levels.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to Mohamed Sharaf, MD, Majdy Bahhar, MD, and Emma Lanuti, MD, for assisting us with dermatopathological evaluation of the samples and to Carol B. Kittles for her work with the institutional review board. We have no relevant financial support or conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1. Sen CK, Gordillo GM, Roy S, Kirsner R, Lambert L, Hunt TK, Gottrup F, Gurtner GC, Longaker MT. Human skin wounds: a major and snowballing threat to public health and the economy. Wound Repair Regen 2009;17:763–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Margolis DJ, Allen‐Taylor L, Hoffstad O, Berlin JA. The accuracy of venous leg ulcer prognostic models in a wound care system. Wound Repair Regen 2004;12:163–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rice JB, Desai U, Cummings AK, Birnbaum HG, Skornicki M, Parsons N. Burden of venous leg ulcers in the United States. J Med Econ 2014;17:347–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Raffetto JD. Inflammation in chronic venous ulcers. Phlebol/Venous Forum R Soc Med 2013;28(Suppl 1):61–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Weinstein DA, Kirsner RS. Refractory ulcers: the role of tumor necrosis factor‐alpha. J Am Acad Dermatol 2010;63:146–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ashcroft GS, Jeong MJ, Ashworth JJ, Hardman M, Jin W, Moutsopoulos N, Wild T, McCartney‐Francis N, Sim D, McGrady G, Song XY, Wahl SM. Tumor necrosis factor‐alpha (TNF‐alpha) is a therapeutic target for impaired cutaneous wound healing. Wound Repair Regen 2012;20:38–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Charles CA, Romanelli P, Martinez ZB, Ma F, Roberts B, Kirsner RS. Tumor necrosis factor‐alfa in nonhealing venous leg ulcers. J Am Acad Dermatol 2009;60:951–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mattey DL, Gonzalez‐Gay MA, Garcia‐Porrua C, Thomson W, Hajeer AH, Ollier WE. Influence of HLA‐DRB1 and TNF microsatellite polymorphisms on the expression of extraarticular manifestations in rheumatoid arthritis patients from northwest Spain. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2001;19:703–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wallace HJ, Vandongen YK, Stacey MC. Tumor necrosis factor‐alpha gene polymorphism associated with increased susceptibility to venous leg ulceration. J Invest Dermatol 2006;126:921–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Streit M, Beleznay Z, Braathen LR. Topical application of the tumour necrosis factor‐alpha antibody infliximab improves healing of chronic wounds. Int Wound J 2006;3:171–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Administration FaD . Highlights of prescribing information of Humira, 2011. URL http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/125057s0215lbl.pdf [accessed on 25 June 2015]

- 12. Margolis DJ, Berlin JA, Strom BL. Which venous leg ulcers will heal with limb compression bandages? Am J Med 2000;109:15–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Markham T, Mullan R, Golden‐Mason L, Rogers S, Bresnihan B, Fitzgerald O, Fearon U, Veale DJ. Resolution of endothelial activation and down‐regulation of Tie2 receptor in psoriatic skin after infliximab therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006;54:1003–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]