Abstract

Numerous comorbidities and cofactors have been known to influence wound healing processes. In this multicentre study, clinical data of 1 000 patients with chronic leg ulcers from ten specialised dermatological wound care centers were analysed. The patient cohort comprised 567 females and 433 males with an average age of 69·9 years. The wounds persisted on average for 40·8 months and had a mean size of 43·7 cm2. Venous leg ulcers represented the most common entity accounting for 51·3% of all chronic wounds, followed by mixed‐type ulcers in 12·9% and arterial ulcerations in 11·0% of the patients. Vasculitis was diagnosed in 4·5%, trauma in 3·2%, pyoderma gangrenosum in 2·8%, lymphoedema in 1·7%, neoplasia in 1·0% and delayed post‐surgical wound healing in 0·6% of the included patients. In total, 70·5% of patients suffered from arterial hypertension, 45·2% were obese, 27·2% had non‐insulin dependent diabetes, and 24·4% dyslipidaemia. Altogether 18·4% suffered from metabolic syndrome. Cofactors and comorbidities of patients with chronic leg ulcers have previously been studied but not in detail. Here, we were able to demonstrate the existence of several potentially relevant cofactors, comorbidities of their associations and geographical distributions, which should be routinely examined in patients with chronic leg ulcers and – if possible – treated.

Keywords: Chronic wound, Cofactors, Comorbidities, Leg ulcer, Metabolic syndrome

Introduction

Chronic wounds represent a growing medical and economical problem worldwide 1. Neither prevalence nor incidences of chronic wounds are centrally recorded in most countries including Germany. However, it is assumed that between two and four million people in Germany suffer from chronic wounds of diverse aetiologies 2. These chronic wounds predominantly manifest as leg ulcers, diabetic foot syndrome, pressure ulcers or wounds secondary to peripheral occlusive arterial disease (POAD) 3, 4, 5. The subgroup of patients suffering from chronic leg ulcers is the most heterogeneous one. Recent studies showed that the diagnosis and clinical evaluation of underlying pathologic mechanisms represent an essential pharmaco‐economic factor not least because of their influence of treatment 6. As an example, patients with chronic venous insufficiency (CVI) need sufficient compression therapy, and in advanced states need invasive methods like varicose vein stripping or sclerosing also. Arterial or mixed leg ulcers (POAD and CVI) require treatment with rheological drugs or interventional revascularisation 7. In more rarely diagnosed entities sustaining chronic wounds like vasculitis, pyoderma gangrenosum, and calciphylaxis, the therapeutic concept is guided by the underlying immunologic or anatomic disorders and, thus, requires different budgetary resources 3. Moreover, different kinds of comorbidities like metabolic syndrome, arterial hypertension and diabetes mellitus and intake of immunosuppressive drugs are suggested to influence wound healing, but are mostly not considered in previous studies 8, 9. Other important aspects are cofactors like age, gender, ulcer size, duration and bacterial colonisation which have been recently reported to affect wound healing and impact therapy costs 10.

So far, only a few single‐centre studies are available addressing these questions in Germany 1, 8, 11. As a consequence, the aim of this nationwide study is the analysis of the aetiology of chronic leg ulcers in addition to comorbidities and cofactors in 1 000 patients from 10 specialised dermatological wound care centers in different regions of Germany.

Methods and patients

Wound care centers

The data for this multicentre study were collected from 10 specialised dermatological wound care centers located in five different geographic regions in Germany (northern region: Kiel and Hamburg; southern region: Regensburg and Munich; western region: Essen and Bochum; eastern region: Magdeburg and Dresden; middle region: Erlangen and Frankfurt). All participating clinics were members of the Working Group Wound Healing [(Arbeitsgemeinschaft Wundheilung (AGW)] of the German Society of Dermatology [Deutsche Dermatologische Gesellschaft (DDG)] to ensure uniform diagnostic and therapeutic standards.

Patient‐related data

In this study in each centrum, 100 successive patients with chronic leg ulcers were admitted. Following national guidelines, a leg ulcer was classified as chronic when it had been present for at least 8 weeks and located on the lower leg between knee and ankle 12. Pressure or other ulcers of the feet or other anatomic regions were excluded. We defined no other exclusion criteria, for example in terms of age, genesis or ulcer size.

The analysis of the aetiology, comorbidities and cofactors was carried out retrospectively using the patient records in the different centres. Besides hardcopy patient files (Dresden, Kiel, Munich, Regensburg), electronic clinical information systems like SOARIAN® (SIEMENS, Erlangen) were used in Hamburg and Erlangen; MEDOS® (NEXUS, Villingen‐Schwenningen) in Magdeburg; and ORBIS® (Agfa Health Care, Bonn) in Essen, Bochum, Dresden and Frankfurt am Main.

Diagnostics

In order to determine aetiology and pathologic mechanisms, all centres used, in addition to a detailed anamnesis and clinical examination, uniform diagnostic procedures and classifications based on national guidelines 13. For example, CVI was diagnosed using colour‐coded Duplex ultrasound. POAD was assessed by measuring the arterial brachial index (ABI) and/or by consulting with an angiological or vascular surgeon with ultrasound expertise. In patients with unclear diagnosis, biopsies were carried out 6 (Table 1). The evaluation of the comorbidities, cofactors and medication was based on patients' history, which was cross‐checked with pre‐existing patient files from other departments or by communicating with the general practitioner (GP). Presence of metabolic syndrome, also known as syndrome X, was defined according to the guidelines of the American Heart Association (AHA), the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI), the World Health Organisation (WHO), the German Society for Diabetes (Deutsche Diabetes Gesellschaft, DDG) and the American Diabetes Association (ADA) 14, 15. For example, the threshold for obesity (WHO) was set to a body mass index (BMI) value of ≥30, hypertension to a systolic blood pressure of ≥130 mmHg or a diastolic value of ≥85 mmHg (AHA/NHLBI), and dyslipidaemia to fasting triglyceride level concentration of ≥150 mg/dl, and a HDL fraction of <50 mg/dl (female) and <40 mg/dl (male) (AHA/NHLBI). The diagnosis of diabetes mellitus type II [non‐insulin dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM)] was made when the fasting blood sugar value exceeded at least twice the concentration of 100 mg/dl (5·6 mM/M; AHA/NHLBI) or exceeded 200 mg/dl (11·1 mM/M) either after 2 hours in a standardised oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) or in a random blood sugar test (WHO) or when the HbA1c value was >6·5% (48 mM/M; DDG/ADA). If three of these criteria were present, metabolic syndrome was documented 14, 15. Neither comorbidity therapy nor ulcer treatment data were collected or evaluated in this investigation.

Table 1.

Diagnostic criteria for ulcer entity

| Ulcer entity | Diagnostic basic criteria |

|---|---|

| Venous | Clinical presentation and ultrasound/duplex diagnostic |

| Arterial | Ankle‐brachial index (ABI) |

| Vasculitis | Histopathologic results from biopsies |

| Post‐traumatic | Anamnesis |

| Pyoderma gangraenosum | Diagnosis of exclusion with typical clinical appearance + biopsy |

| Lymphoedema | Clinical appearance |

| Neoplasm | Histopathologic results from biopsies |

| Post‐surgery | Anamnesis |

Statistical analysis

Data were binary coded and quantitatively recorded in an Excel 2003™ (Microsoft). Then, the data were transferred to SPSS 19™, Software for Predictive Analytics (IBM, Ehningen) for analysis. The numbers were estimated using descriptive statistics. Coherences were calculated using Pearson's bivariate correlations. Significance was tested with Fisher's double‐sided chi‐Quadrat test. The correlation was classified as significant at the level of 0·01 (two‐sided) or 0·05 (two‐sided).

Results

Patients

In total, data from 1 000 patients with chronic leg ulcers were analysed (567 females and 433 males). The oldest patient was 100 years and the youngest was 10 years; the mean age was 69·9 years. On average, the wounds persisted for 40·8 months, with a maximum of 816 months and a minimum of 8 weeks. In 665 patients (66·5%), the wounds persisted for less than 2 years and in 335 patients (33·5%) for 2 years or longer. In 955 patients, a quantitative size of the wounds was documented. The ulcer sizes ranged between 1 mm2 and 736 cm2 with an average size of 43·7 cm2.

Aetiologies

Venous leg ulcers represented the most common entity accounting for 51·3% of all chronic wounds, followed by mixed‐type ulcers (venous and arterial) in 12·9% and arterial ulcerations in 11·0% of the patients. Vasculitis was diagnosed as the underlying cause in 4·5%, trauma in 3·2%, pyoderma gangrenosum in 2·8%, lymphoedema in 1·7%, neoplasia in 1·0%, and delayed post‐surgical wound healing in 0·6% of the included patients. In 11·0% of patients, the exact aetiology could not be unravelled based on the patient health record available. Altogether, 46·7% of the patients with chronic venous ulcers underwent at least one episode of thrombosis prior to ulceration or developed a post‐thrombotic syndrome (Table 2).

Table 2.

Aetiology of chronic leg ulcers in Germany

| Aetiology | Incidence (absolute) | Incidence (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Venous leg ulcer | 513 | 51·3 |

| Mixed leg ulcer | 129 | 12·9 |

| Arterial leg ulcer | 110 | 11·0 |

| Vasculitis | 45 | 4·5 |

| Post‐traumatic ulcer | 32 | 3·2 |

| Pyoderma gangrenosum | 28 | 2·8 |

| Lymphoedema | 17 | 1·7 |

| Neoplasms | 10 | 1·0 |

| Post‐surgical ulcer | 6 | 0·6 |

| Unclear | 110 | 11·0 |

| Total | 1 000 | 100 |

Comorbidities

In the examined study cohort (n = 1 000), 70·5% of patients suffered from arterial hypertension (AHA/NHBLI), 27·2% from non‐insulin‐dependent diabetes mellitus (WHO/DDG/ADA) and 24·4% from dyslipidaemia (AHA/NHBLI). Totally 45·2% (n = 746) presented with a BMI of ≥30 and were classified as morbidly obese according to the current definition of the WHO. The different combinations of comorbidities found in the cohort are displayed in Table 3. For example, hypertension as a single comorbidity was seen in 25·5% of the evaluated patients. A combination of hypertension and obesity was observed in 12·7%, whereas hypertension plus diabetes mellitus was detected less frequently in 8·6% of the patients. Altogether 7·7% of the patients suffered from hypertension, obesity and diabetes mellitus; 3·6% from hypertension, dyslipidaemia and obesity; and 3·1% additionally developed diabetes mellitus. Four comorbidities such as hypertension, obesity, dyslipidaemia and diabetes mellitus were diagnosed in 4·0%. In total 18·4% of all patients had metabolic syndrome, and no relevant comorbidities could be identified in 19·9% of patients.

Table 3.

Comorbidities and chronic leg ulcers

| Numbers | Cofactors | Incidence (absolute) | Incidence (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hypertension | 255 | 25·5 |

| Obesity | 39 | 3·9 | |

| NIDDM | 25 | 2·5 | |

| Dyslipidaemia | 13 | 1·3 | |

| 2 | Hypertension, obesity | 127 | 12·7 |

| Hypertension, NIDDM | 86 | 8·6 | |

| Hypertension, dyslipidaemia | 53 | 5·3 | |

| Obesity, NIDDM | 12 | 1·2 | |

| Obesity, dyslipidaemia | 6 | 0·6 | |

| Dyslipidaemia, NIDDM | 1 | 0·1 | |

| 3 | Hypertension, obesity, NIDDM | 77 | 7·7 |

| Hypertension, obesity, dyslipidaemia | 36 | 3·6 | |

| Hypertension, dyslipidaemia, NIDDM | 31 | 3·1 | |

| 4 | Hypertension, NIDDM, obesity, Dyslipidaemia | 40 | 4·0 |

| 0 | No relevant cofactors | 199 | 19·9 |

| Total | 1 000 | 100·0 |

NIDDM, non‐insulin‐dependent diabetes milletus.

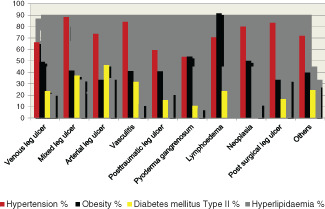

Association of single comorbidities with distinct ulcer entities

Arterial hypertension was found in 88·4% of all patients with mixed‐type leg ulcers, in 84·2% of patients with vasculitis‐associated ulcers, and in 53·6% of patients with pyoderma gangrenosum. Hypertension was also documented in 83·3% of patients with post‐surgical ulcers and in 80·0% of patients with neoplastic ulcers (Table 3, Figure 1). With regard to obesity, there was an association with 91·6% of lymphoedemas, 53·8% of pyoderma gangrenosum, 50·0% of neoplastic ulcers, 49·2% of venous leg ulcers, and 33·3% of arterial leg ulcers and post‐surgical wounds (Table 4, Figure 1). Diabetes was found as a comorbidity in 46·4% of patients with arterial leg ulcers, 37·2% with mixed leg ulcers, 31·6% with vasculitis, 23·6% with venous leg ulcers, and 23·5% with lymphoedema (Table 4, Figure 1). Association with dyslipidaemia was seen in 34·9% of patients with arterial leg ulcers, 33·7% with mixed leg ulcers and 33·3% with post‐surgical ulcers (Table 4, Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Comorbidities in relation to aetiology.

Table 4.

Comorbidities in relation to aetiology of chronic leg ulcers

| Hypertension | NIDDM | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aetiology | n | Absolute | % | n | Absolute | % |

| Venous leg ulcer | 513 | 340 | 66·2 | 513 | 121 | 23·6 |

| Mixed leg ulcer | 129 | 114 | 88·4 | 129 | 48 | 37·2 |

| Arterial leg ulcer | 110 | 81 | 73·6 | 110 | 51 | 46·4 |

| Vasculitis | 45 | 32 | 84·2 | 45 | 12 | 31·6 |

| Post‐traumatic ulcer | 32 | 19 | 59·4 | 32 | 5 | 15·6 |

| Pyoderma gangrenosum | 28 | 15 | 53·6 | 28 | 3 | 10·7 |

| Lymphoedema | 17 | 12 | 70·6 | 17 | 4 | 23·5 |

| Neoplasm | 10 | 8 | 80·0 | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| Post‐surgical ulcer | 6 | 5 | 83·3 | 6 | 1 | 16·7 |

| Unclear | 110 | 79 | 71·8 | 110 | 27 | 24·5 |

| Total | 1 000 | 705 | 70·5 | 1 000 | 272 | 27·2 |

| Obesity | Dyslipidaemia | |||||

| Aetiology | n | Absolute | % | n | Absolute | % |

| Venous leg ulcer | 372 | 183 | 49·2 | 377 | 80 | 21·2 |

| Mixed leg ulcer | 101 | 42 | 41·6 | 98 | 33 | 33·7 |

| Arterial leg ulcer | 90 | 30 | 33·3 | 83 | 29 | 34·9 |

| Vasculitis | 34 | 14 | 41·2 | 33 | 4 | 12·1 |

| Post‐traumatic ulcer | 22 | 9 | 40·9 | 23 | 5 | 21·7 |

| Pyoderma gangrenosum | 13 | 7 | 53·8 | 12 | 1 | 8·3 |

| Lymphoedema | 12 | 11 | 91·6 | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| Neoplasm | 8 | 4 | 50·0 | 8 | 1 | 12·5 |

| Post‐surgical ulcer | 6 | 2 | 33·3 | 6 | 2 | 33·3 |

| Unclear | 88 | 35 | 39·7 | 88 | 25 | 28·4 |

| Total | 746 | 337 | 45·2 | 738 | 180 | 24·4 |

NIDDM, non‐insulin‐dependent diabetes milletus.

Association of metabolic syndrome with ulcer entities

The most common proportion of metabolic syndrome in relation to the aetiology was found in patients with vasculitis‐associated chronic wounds (51·1%). Moreover, metabolic syndrome was diagnosed in 33·3% of patient with post‐surgical ulcers, 25·6% of patients with mixed‐type ulcers, 24·6% with arterial leg ulcers, 20·0% with neoplasms, 17·7% with lymphoedema, 16·4% with venous leg ulcers, 15·6% with post‐traumatic ulcers, and 14·3% with pyoderma gangrenosum (Table 5).

Table 5.

Metabolic syndrome in relation to the aetiology of chronic leg ulcers

| Metabolic syndrome | Aetiology | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute | % Related to the absolute values of 184 | Absolute | % Proportion of the metabolic syndrome in relation to the aetiology | |

| Venous leg ulcer | 84 | 45·7 | 513 | 16·4 |

| Mixed leg ulcer | 33 | 17·9 | 129 | 25·6 |

| Arterial leg ulcer | 27 | 14·7 | 110 | 24·5 |

| Vasculitis | 23 | 12·5 | 45 | 51·1 |

| Post‐traumatic ulcer | 5 | 2·7 | 32 | 15·6 |

| Pyoderma gangrenosum | 4 | 2·2 | 28 | 14·3 |

| Lymphoedema | 3 | 1·6 | 17 | 17·7 |

| Neoplasm | 2 | 1·1 | 10 | 20·0 |

| Post‐surgical ulcer | 2 | 1·1 | 6 | 33·3 |

| Unclear | 1 | 0·5 | 110 | 10·0 |

| Total | 184 | 100 | 1 000 | 18·4 |

Distribution of ulcer entities across different geographic regions in Germany

Significantly more patients with CVI were seen in the western (n = 124) compared with those of the middle (n = 89, P = 0·0006), the southern (n = 92, P = 0·0018) and the northern regions of Germany (n = 101, P = 0·0204), but not more than those of the East (n = 107, P = 0·1052). In contrast, POAD was the least common ulcer entity in the West (n = 14) and the most common entity in the North (n = 30; P = 0·0157). Mixed‐type leg ulcers were more common in the East (n = 32, P = 0·0319) and West (n = 31, P = 0·0446) than in the North (n = 17). Vasculitis (35·5%) and trauma (37·5%) were diagnosed more often in the middle regions of Germany than in the other regions (ranging between 11·1–22·2% and 9·4–21·8%, respectively). Pyoderma gangrenosum was more prevalent in the North (50·0%) than in the other regions (0–28·6%). Post‐surgical ulcerations and ulcers secondary to neoplasia were distributed evenly among the five regions (Table 6).

Table 6.

Aetiology of chronic leg ulcers in the different regions

| Region | CVI | Mixed | POAD | Vasculitis | Trauma | PG | Lymphoedema | Neoplasm | OP | unclear |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| West (n = 200) | 124 | 31 | 14 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 15 |

| North (n = 200) | 101 | 17 | 30 | 5 | 7 | 14 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 20 |

| East (n = 200) | 107 | 32 | 25 | 9 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 16 |

| Middle (n = 200) | 89 | 24 | 20 | 16 | 12 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 22 |

| South (n = 200) | 92 | 25 | 21 | 10 | 6 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 37 |

| Total | 513 | 129 | 110 | 45 | 32 | 28 | 17 | 10 | 6 | 110 |

CVI, chronic venous insufficiency; POAD, peripheral occlusive arterial disease; PG, pyoderma gangrenosum.

Comorbidities in different regions

From the geographic distribution of the comorbidities, it was apparent that all four were most common in the East. Hypertension was significantly more common than in the West (P = 0·0001) and the North (P = 0·0001). Diabetes mellitus was significantly more prevalent in the East (West, P = 0·0207; South, P = 0·0082; North and Middle, P = 0·0001) (Table 7).

Table 7.

Comorbidities in different regions of Germany

| Region | Hypertension | Obesity | NIDDM | Dyslipidaemia |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| West (n = 200) | 122 | 63 | 58 | 30 |

| North (n = 200) | 125 | 38 | 38 | 41 |

| East (n = 200) | 162 | 85 | 81 | 49 |

| Middle (n = 200) | 149 | 73 | 40 | 29 |

| South (n = 200) | 147 | 78 | 55 | 31 |

| Total | 705 | 337 | 272 | 180 |

NIDDM, non‐insulin dependent diabetes mellitus.

Association of cofactors with ulcer entities

A patients' age was significantly correlated with arterial and mixed‐type leg ulcers (P = 0·022; P = 0·001), whereas a younger age was correlated with lymphoedema or pyoderma gangrenosum (P = 0·01; P = 0·001). Venous ulcers showed a significant positive correlation (P = 0·002) with the persistence of the wounds, whereas pyoderma gangrenosum was negatively correlated (P = 0·039). This suggests that the longer a wound exists, the higher the probability that a chronic vascular insufficiency is the reason and vice versa. Female gender was significantly associated with venous leg ulcers (P = 0·018), while male gender rather predisposed to arterial leg ulcers (P = 0·002). With regard to the size of ulcers, there was no significant correlation detected (Table 8).

Table 8.

| Aetiology | Correlation | Gender | Age | Duration | Size (cm2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CVI | Pearson's correlation | 0·075* | –0·027 | 0·098** | –0·006 |

| Significance (two‐sided) | 0·018 | 0·387 | 0·002 | 0·855 | |

| POAD | Pearson's correlation | –0·100** | 0·072* | –0·056 | 0·024 |

| Significance (two‐sided) | 0·002 | 0·022 | 0·080 | 0·459 | |

| Mixed | Pearson's correlation | 0·017 | 0·104** | –0·003 | 0·056 |

| Significance (two‐sided) | 0·603 | 0·001 | 0·933 | 0·086 | |

| Vasculitis | Pearson's correlation | 0·004 | –0·039 | –0·056 | 0·007 |

| Significance (two‐sided) | 0·892 | 0·218 | 0·079 | 0·826 | |

| Trauma | Pearson's correlation | –0·110 | –0·200 | 0·225 | –0·154 |

| Significance (two‐sided) | 0·391 | 0·115 | 0·076 | 0·232 | |

| Surgical | Pearson's correlation | 0·023 | –0·144 | –0·099 | –0·148 |

| Significance (two‐sided) | 0·892 | 0·390 | 0·556 | 0·375 | |

| Neoplasm | Pearson's correlation | 0·112 | 0·122 | –0·276 | 0·006 |

| Significance (two‐sided) | 0·481 | 0·443 | 0·077 | 0·968 | |

| Lymphoedema | Pearson's correlation | 0·170 | –0·366** | 0·021 | –0·077 |

| Significance (two‐sided) | 0·243 | 0·010 | 0·885 | 0·609 | |

| PG | Pearson's correlation | 0·138 | –0·428** | –0·268* | –0·038 |

| Significance (two‐sided) | 0·292 | 0·001 | 0·039 | 0·779 |

CVI, chronic venous insufficiency; POAD, peripheral occlusive arterial disease; PG, pyoderma gangrenosum.

The correlation is at the level of 0·01 (two‐sided) significant.

The correlation is at the level of 0·05 (two‐sided) significant.

Discussion

Besides the commonly known causes of chronic leg ulcers such as CVI and POAD 16, 17, there are various comorbidities and cofactors, which additionally may affect wound healing, but are not yet considered in most therapeutic concepts. There are only few clinical studies available regarding the possible association between aetiologies, cofactors and comorbidities in patients with chronic leg ulcers in Germany. In a previous study by our group, wound experts of different medical specialisations collected data of more than 30 000 patients with chronic leg ulcers, however, primarily focussing on the respective aetiologies of ulcers 1. Cofactors or comorbidities were not included in the study questionnaires. Thus, in this study, we intended to (1) confirm the previously reported aetiologies and (2) correlate those with relevant clinical comorbidities and cofactors.

This analysis indicates that venous leg ulcers are most common in 51·3% of patients, followed by mixed‐type leg ulcers in 12·9% and arterial leg ulcers in 11·0% 1. The latter entities, however, were seen less often as compared with those of our previous study. These differences are most likely due to a patient selection bias caused by the heterogeneous composition of the contributing investigators coming from different medical disciplines 1 (Table 2). For example in Germany, vascular surgeons or angiologists are predominantly consulted by patients with suspected arterial disease, whereas ulcers originating from venous disease are treated by phlebologically skilled experts like dermatologists. This explanation is also supported by a study from Hamburg, in which 23% of patients with chronic leg ulcers had an underlying arterial disease. This study was also carried out in different hospitals and specialities including vascular surgical departments 18. Our present study involved only specialised dermatological wound centres. This could have resulted in an over‐representation of patients with CVI.

Comorbidities nationwide

As diverse as the aetiology of chronic leg ulcers is the distribution of comorbidities. The metabolic syndrome, defined by the presence of at least three of the factors, hypertension, obesity, dyslipidaemia and impaired glucose tolerance, represents a growing medical and economic problem in western countries like Germany 19. A recent estimation by the institute of operational health promotion (Institut für Betriebliche Gesundheitsförderung, BGF) of the general local health insurance (Allgemeine Ortskrankenkasse, AOK) indicates that 20 million people in Germany fulfilled the diagnostic criteria of the metabolic syndrome 20. In our study, 18·4% of the patients were affected by metabolic syndrome (Table 5), which signifies that in addition to the underlying aetiology and disease in chronic, non‐healing wounds, more risk factors, which may affect healing, have to be considered.

Our findings show that 53·6% of patients with chronic leg ulcers suffered from arterial hypertension. This was mostly seen in patients with vascular aetiology ulcers. The combination of hypertension coincided with mixed leg ulcers (88·4%), vasculitis (84·2%), arterial ulcers (73·6%) and venous ulcers (73·6%) (Table 4). This association could be owing to combined pathological mechanisms resulting in degenerative venous vessels, atherosclerotic plaques and subsequent inflammatory processes 21.

In 45·2% of the patients in our study, obesity was recorded. Particularly the association of lymphoedema (91·6%) and pyoderma gangrenosum (91·6%) with obesity was noticeable (Table 4). The high relationship between lymphoedema and obesity could be explained by the lack of physical activity in obese patients and subsequent lymphatic stasis. Additionally some of the female patients demonstrate an accompanied lipoedema, which predisposes to lymphatic drainage impairment 22, 23. For patients with pyoderma gangrenosum, obesity has been already discussed as a relevant cofactor in 32·6% of patients in an earlier study 24. These data are comparable with our results, but the exact pathologic mechanisms of this association are not yet clear. One theory is that a perpetuating chronic systemic Th1‐induced inflammatory reaction mediated amongst others by TNF‐α, interleukin‐1, interleukin‐6 and adipokines can deteriorate chronic wounds 24.

Diabetes mellitus and dyslipidaemia were present in more than one‐third of the patients with arterial and mixed ulcers (Table 4). It has been discussed that the atherosclerotic modifications of blood vessels facilitated by the comorbidities hyperglycaemia and hyperlipidaemia may lead to deficiencies of oxygen, nutrition and neural supply 21. The risk in patients with at least three comorbidities of the metabolic syndrome was demonstrated in association with the numbers of vascular‐related chronic ulcers. Currently the frequency of these metabolic syndrome factors was found in more than half of vasculitis associated, and approximately a quarter of arterial, mixed, and venous leg ulcer patients (Table 5). In total, comorbidities that manifest in the arterial system are many in patients with arterial or mixed leg ulcers 21, 25.

Next to comorbidities, clinical cofactors may influence healing of chronic wounds (Table 8). In our analysis, patients' age was associated with POAD (P = 0·022) and CVI (P = 0·001). This could be explained by progressive atherosclerotic alterations in blood vessels increasing with age. In contrast, an inverse correlation of age with lymphoedema and pyoderma gangrenosum was found. This association is confirmed by other studies showing a peak of lymphoedema between 15 and 35 years and of pyoderma gangrenosum between 20 and 50 years of age 26, 27. CVI was significantly associated with long persistence of wounds and with age. This correlation could be confirmed by other reports 9, 28. Under pathophysiological aspects, this is confusing because theoretically CVI is a well treatable disease if the patients are willing to undertake the necessary interventions 29. Our investigation was conducted in specialised dermatological wound care centers only. As shown in a current analysis from our center, patients with chronic leg ulcers present themselves firstly in an average of 17·5 months after the appearance of an ulcer. Initially, most of the patients consulted their GPs at the first instance who tried to treat them, in an average, over a period of 1·5 years. In Germany, specialised wound care centers are approached only if the earlier treatment method failed after longer time periods of treatment 30. The approach of patients through different sectors of the health system can be very different in various countries.

Pyoderma gangrenosum, however, showed a significantly negative correlation with the persistence of wounds. This is probably owing to the sudden development and the high intensity of pain 31.

As a clinical and economic consequence, we believe that it is very important to determine the comorbidities and cofactors in patients with chronic leg ulcers because it is more and more evident that these factors directly or indirectly influence wound healing.

Conclusion

In this nationwide retrospective multicentre study, we analysed the clinical and aetiological spectrum of patients with chronic leg ulcers in Germany. Ten specialised dermatological wound care centers contributed to this data collection. Clinically important correlations between aetiology, comorbidities and cofactors of patients with chronic leg ulcers were determined. So far, such correlations are rarely considered in daily routine despite their potential relevance for wound healing. As a fundamental conclusion we would like to suggest that comorbidities and cofactors of patients with chronic wounds should be consistently examined, recorded, and – if possible – treated based on interdisciplinary standards.

Acknowledgement

All authors of the article declare that there exist no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Körber A, Klode J, Al‐Benna S, Wax C, Schadendorf D, Steinsträsser L, Dissemond J. Genese des chronischen Ulcus cruris bei 31·619 Patienten im Rahmen einer Expertenbefragung in Deutschland. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2011;9:116–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.AWMF‐Register Nr. 091/001. S3‐Leitlinie der deutschen Gesellschaft für Wundheilung und Wundbehandlung e.V. (DGfW). Lokaltherapie chronischer Wunden bei Patienten mit den Risiken periphere arterielle Verschlusskrankheit, Diabetes mellitus, chronische venöse Insuffizienz, 2012.

- 3. Dissemond J. Ulcus cruris – Genese, Diagnostik, Therapie, 4 edn. Bremen: Auflage; Unimed Verlag, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Graham ID, Harrison MB, Nelson EA, Lorimer K, Fisher A. Prevalence of lower limb ulceration: a systemic review of prevalence studies. Adv Skin Wound Care 2003;16:305–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Purwins S, Herberger K, Debus S, Rustenbach SJ, Pelzer P, Rabe E, Schäfer E, Stadler R, Augustin M. Cost‐of‐illness of chronic leg ulcers in Germany. Int Wound J 2010;7:97–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wozniak G, Mauckner P, Steinsträsser L, Dissemond J. Standardisierte Wundtherapie. Gefässchirurgie 2011;16:281–92. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kranke P, Bennett M, Roeckl‐Wiedmann I, Debus S. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for chronic wounds. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;2:CD004123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. O'Brien JF, Grace PF, Perry IJ, Burke PE. Prevalence and aetiology of leg ulcers in Ireland. Ir J Med Sci 2000;169:110–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Meaume S, Couilliet D, Vin F. Prognostic factors for venous ulcer healing in a non‐selected population of ambulatory patients. J Wound Care 2005;14:31–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Moffatt CJ, Doherty DC, Smithdale R, Franks PJ. Clinical predictors of leg ulcer healing. Br J Dermatol 2010;162:51–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jockenhöfer F, Gollnick H, Herberger K, et al. Bacteriological pathogen spectrum of chronic leg ulcers: Results of a multicenter trial in dermatologic wound care centers differentiated by regions. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2013;11:1057–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.AWMF‐Register Nr. 037/009. S3‐Leitlinie der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Phlebologie (DGP). Diagnostik und Therapie des Ulcus cruris venosum, 2008.

- 13.AWMF‐Register Nr. 065/003. S3‐Leitlinie der deutschen Gesellschaft für Angiologie, Gesellschaft für Gefäßmedizin. Leitlinien zur Diagnostik und Therapie der peripheren arteriellen Verschlusskrankheit (pAVK), 2009.

- 14. Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, Donato KA, Eckel RH, Franklin BA, Gordon DJ, Krauss RM, Savage PJ, Smith SC Jr, Spertus JA, Costa F; Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute scientific statement. Circulation 2005;112:2735–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Alberti KG, Zimmet P, Shaw J. IDF epidemiology task force consensus group. The metabolic syndrome – a new worldwide definition. Lancet 2005;366:1059–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Moffat CJ, Franks PJ, Dohetty DC, Martin R, Blewett R, Ross F. Prevalence of leg ulceration in a London population. Q J Med 2004;97:431–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Baker SR, Stacy MC, Singh G, Hoskin SE, Thompson PJ. Aetiology of chronic leg ulcers. Eur J Vasc Surg 1992;6:2452–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Herberger K, Rustenbach SJ, Grams L, Münter KC, Schäfer E, Augustin M. Quality‐of‐care for leg ulcers in the metropolitan area of Hamburg – A community‐based study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2012;26:495–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.BGF Institut 2011. Zeitbombe im Betrieb: Das metabolische Syndrom. Strategien und Hinweise für Unternehmen. www.bgf‐institut.de.

- 20. Neuhauser H, Ellert U. Prävalenz des metabolischen Syndroms in Deutschland: eine Sensitivitätsanalyse. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Medizinische Informatik, Biometrie und Epidemiologie. Deutsche Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Epidemiologie. 50. Jahrestagung der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Medizinische Informatik, Biometrie und Epidemiologie (gmds), 12. Jahrestagung der Deutschen Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Epidemiologie. Freiburg im Breisgau, 12.‐15.09.2005. Düsseldorf, Köln: German Medical Science, 2005. Doc05gmds416. http://www.egms.de/en/meetings/gmds2005/05gmds183.shtml.

- 21. Espinola‐Klein C, Savvidis S. Periphere arterielle Verschlusskrankheit. Epidemiologie, Klinik und Diagnostik. Internist 2009;50:919–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Brauer WJ, Weissleder H. Methodik und Ergebnisse der Funktionslymphszintigraphie: Erfahrungen bei 924 Patienten. Phlebologie 2002;5:118–25. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bilancini S, Lucchi M, Tucci S, Eleuteri P. Functional lymphatic alterations in patients suffering from lipedema. Angiology 1995;46:3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Al Ghazal P, Körber A, Klode J, Dissemond J. Untersuchung neuer Kofaktoren bei 49 Patienten mit Pyoderma gangraenosum. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2012;10:251–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Garg PK, Biggs ML, Carnethon M, Ix JH, Criqui MH, Britton KA, Djoussé L, Sutton‐Tyrrell K, Newman AB, Cushman M, Mukamal KJ. Metabolic syndrome and risk of incident peripheral artery disease: the cardiovascular health study. Hypertension 2014;63:413–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wollina U. Pyoderma gangrenosum – a review. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2007;152:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Connell F, Gordon K, Brice G, Keeley V, Jeffery S, Mortimer P, Mansour S, Ostergaard P. The classification and diagnostic algorithm for primary lymphatic dysplasia: an update from 2010 to include molecular findings. Clin Genet 2013;84:303–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Eberhardt RT, Raffetto JD. Contemporary reviews in cardiovascular medicine: chronic venous insufficiency. Circulation 2005;111:2398–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Läuchli S, Bayard I, Hafner J, Hunziker T, Mayer D, French L. Healing times and the need for hospitalization for leg ulcers of different etiologies. Hautarzt 2013;64:917–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stoffels‐Weindorf M, von der Stück H, Klode J, Dissemond J. Treatment process way of patients with chronic wounds in Germany. Results of a prospective study in 100 patients with chronic leg ulcers. Phlebologie 2013;42:183–8. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Su WP, Davis MD, Weenig RH, Powell FC, Perry HO. Pyoderma gangrenosum: clinicopathologic correlation and proposed diagnostic criteria. Int J Dermatol 2004;43:790–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]