Abstract

Haemodialysis is the most frequent form of renal replacement therapy (RRT) in patients with end‐stage renal disorder (ESRD). Patients with ESRD frequently develop skin problems, mainly xerosis, pruritus and hyperpigmentation, as well as bullous diseases, mainly porphyria or pseudoporphyria and, in some cases, bullous pemphigoid (BP). BP is the most common autoimmune sub‐epidermal blistering disease, and it predominantly affects elderly people. Clinically, BP is characterised by generalised pruritic, bullous eruptions and urticaria‐like lesions. Usually, BP is an idiopathic disorder; however, in some cases, underlying internal disorders are present, like diabetes or neurological disorders. Herein, we present a 33‐year‐old man with ESRD, maintained on haemodialysis, who developed BP. There are only six cases with BP provoked by the placement of a fistula for haemodialysis. BP in the current patient was confirmed by direct immunofluorescence (DIF) and indirect immunofluorescence using BIOCHIP. The patient responded promptly to tertracycline and 0·05% clobetasol propionate lesionally. However, the relationship between BP and the fistula for haemodialisys still remains unknown. It is highly likely that the skin injury associated with fistula placement was responsible for the alteration of the basement membrane zone (BMZ) and the stimulation of the immune system, leading to BP development. To explain the real role of fistula placement as a provocative factor in BP, other such cases are required for assessment.

Keywords: BIOCHIP, Bullous pemphigoid, Fistula, Haemodialysis, Renal allograft

Introduction

Haemodialysis is the most frequent form of renal replacement therapy (RRT) in end‐stage renal disorder (ESRD). Although RRT is a lifesaving procedure, it may be responsible for numerous complications, including skin problems. About 50–100% of the patients present with at least one skin problem. Among these, the most common is porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT) and peseudoporphyria; however, bullous pemphigoid (BP) may also appear 1. BP mainly affects people older than 65 years of age; however, it rarely occurs in younger individuals 2, 3, 4. Clinically, BP is characterised by tense blisters located mainly on the flexural surfaces of the extremities and trunk, with severe pruritus in almost all patients. Immunologically, BP is characterised by tissue‐bound and circulating autoantibodies against the 180kD and 230kD, which are hemidesmosomal proteins of the basement membrane zone (BMZ) 2.

Here, we present a case of BP in a haemodialysed patient with ESRD who responded well to mild therapy with the use of tetracycline and topical 0·05% clobetasol propionate.

Case report

We present the case of a 33‐year‐old man who was referred to our department in 2015. In 2007, the patient was diagnosed with ESRD and treated with haemodialysis. As a consequence of ESRD, he developed renal hypertension, which was controlled with amlodipine and metoprolol. In 2008, a renal transplantation was performed, supported by immunosupressive therapy containing prednisone, cyclosporine and mycophenolate mofetil. However, in 2014, kidney transplant was rejected. Therefore, a haemodialysis fistula on the right forearm was performed, and haemodialysis was initiated again. One year later, the patient visited our department because of tense blisters initially located on the forearm along with the fistula. Then, the blisters spread to the left forearm, trunk and knees (Figure 1). Blisters were accompanied by severe pruritus. Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) identified linear deposits of IgG and C3 along the BMZ. Indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) performed on the salt split skin disclosed linear staining of circulating IgG on the epidermal side of the artificial blister. Moreover, the patient's serum revealed reactivity with the recombinant NC16a domain of the BP180 kD BMZ antigen in the BIOCHIP test (Figure 2) 3. Based on these results, we diagnosed BP. The patient was treated with oral tetracycline (1 g/day) plus 0·05% clobetasol propionate lesionally twice a day, which were gradually reduced till discontinuation after 8 months. Blisters and erosions disappeared within 3 weeks without scars. The patient has remained symptom free in the follow‐up lasting 6 months.

Figure 1.

Clinical characterisation of the current patient. (A) Tense blisters located on the forearms before treatment, (B) after treatment.

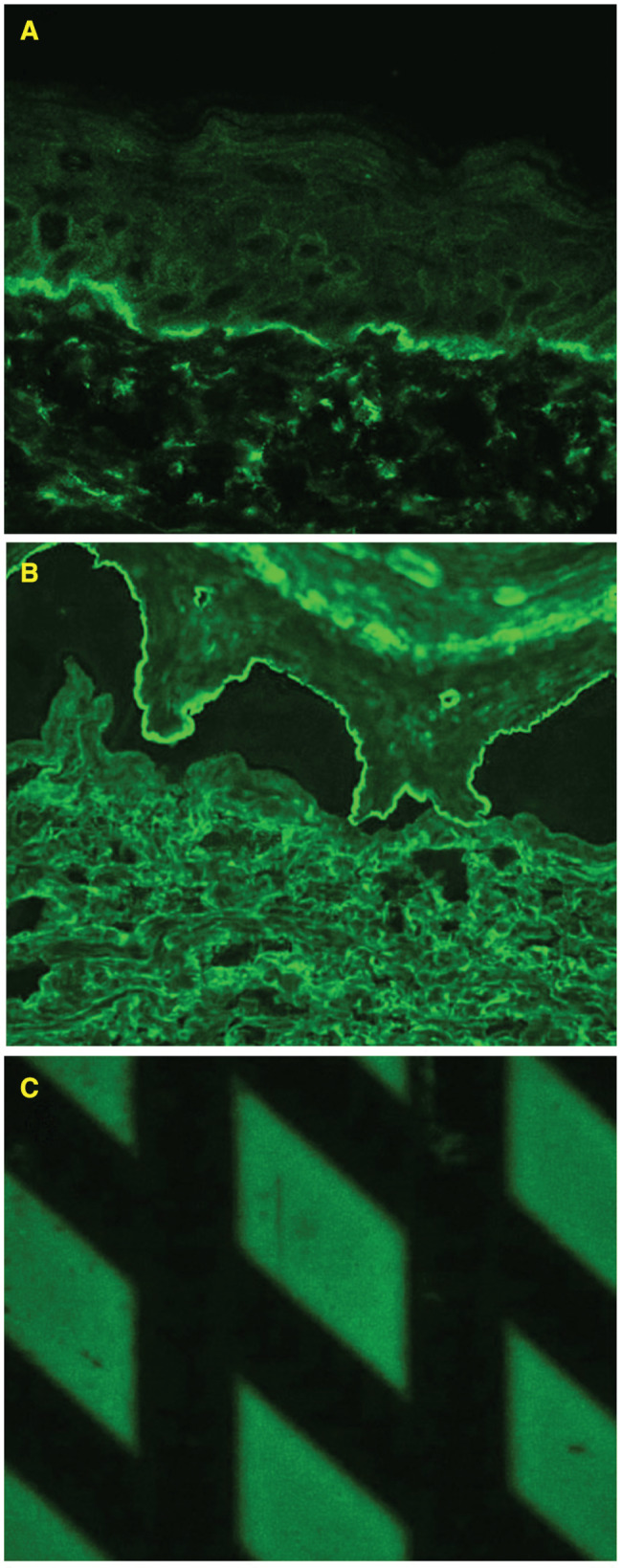

Figure 2.

BIOCHIP: reactivity of circulating IgG with (A) the epidermal side of the salt split skin and (B) recombinant NC16a domain of the BP180 BMZ antigen.

Discussion

BP mainly affects elderly people, and it is considered an idiopathic autoimmune blistering disorder 2. However, there are growing data in the literature on BP provoked by different factors, like medications, UV or skin injuries caused by trauma or surgical procedures 4.

Herein, we present a young patient with ESRD treated with haemodialysis who developed BP. To date, there are only six such cases published in the literature, including ours, three females and three males (details in Table 1) 5, 6, 7, 8, 9. These patients were of different ages when they developed BP; two of them were younger than 52 years of age, and four were 72 years and older. One patient developed BP a short time after the placement of the fistula for haemodialysis 5, whereas in five patients, BP occurred 1–11 years later 6, 7, 8, 9. Most of the patients had coexisting hypertension; 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 two had diabetes mellitus; 5, 7 one had anaemia 6, and another had prostrate cancer and stroke in the anamnesis 9. In only two of them, it was possible to characterise the BP180 BMZ antigen as a target for circulating antibodies using immunoblot 10 or BIOCHIP (our patient), which consists of different antigen substrates, allowing polyvalent immunofluorescence tests, and provides antibody profiles in a single incubation. Patients with ESRD who develop blisters may generate many diagnostic difficulties, the most common of which is PCT or pseudoporphyria. It is known that the clinical picture of patients with BP and ESRD may resemble sporadic PCT or with blisters located on the dorsal hands and face, with hyperpigmentations and hypertrichosis, but the level of uroporphirins in the plasma and urine was normal 1.

Table 1.

Clinical and immunological characterisation of haemodialysed patients who developed bullous pemphigoid

| No. | Case | Gender | Age – performed fistula | Age – BP occurs | Coexisting factors | Time for BP development | Diagnostic procedures | Therapy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Freeman (1997) | F72 | 72 | 72 | Hypertension; Diabetes mellitus | 3 days | DIF: linear deposition of IgG, type IV collagen at the base of the bulla | Prednisone; Tetracycline; Niacinamine |

| 2 | Kamada (1998) | M62 | 62 | 73 | Anaemia, elevation of blood urea nitrogen, creatinine and CRP | n/a | DIF: linear deposition of IgG and C3 | 0·12% Betamethasone valeriane ointment containing 0·1% gentamicin |

| IIF: linear IgG and C3 staining | ||||||||

| IB: 230kD positive 180kD negative | ||||||||

| 3 | Yesudian (2002) | M69 | 69 | 73 | Congestive cardiac failure; mitral regurgitation; atrial fibrillation; cerebrovascular accident (PEG); adenocarcinoma of the prostate | 2 weeks | Skin biopsy: eosinophilis, lymphocytes and plasma cells | Clobetasol propionate (Dermovate NN) |

| DIF: IgG+ and C3+, type IV collagen in the blistered floor | ||||||||

| IIF: elevated antibody levels to skin basement membrane | ||||||||

| 4 | Pardo (2004) | M69 | 69 | 76 | Hypertension, type 2 diabetes; vocal cord epidermoid carcinoma | n/a | DIF: linear deposits of IgG, IgM and C3 at basal membrane level | Prednisone (30 mg/day) |

| 5 | Pardo (2004) | F43 | 43 | 52 | Hypertension, plaque pattern psoriasis | n/a | DIF: linear deposits of IgG, IgM and C3 at basal membrane level | Prednisone (30 mg/day) |

| 6 | Peruzzo (2013) | F15 | 15 | 28 | – | n/a | DIF: IgG and C3 along the dermoepidermal junction | Azathioprine 100 mg and Prednisone 60 mg |

| IIF: linear IgG at the basement membrane zone and epidermal staining with IgG on NaCl‐split skin. | ||||||||

| 7 | Current case | M32 | 32 | 33 | Hypertension | n/a | DIF: linear deposits of IgG at basal membrane level | Tetracycline (1 g/day); Clobetasol Propionate |

| BIOCHIP: BP180+ |

DIF, direct immunofluorescence; IB, immunoblotting; IIF, indirect immunofluorescence.

BP, provoked by external factors like medications or skin injury, is rather a mild condition in terms of response to prognosis and therapy. In our patient, considering a few erosions, we decided to treat him with tetracycline and clobetasol lesionally, which led to the rapid healing of these erosions. Within several months, it was possible to discontinue the therapy as he was in clinical remission for 6 months. Most of the similar patients in the literature were treated with prednisone alone 7 or in combination with azathioprine 8 and tetracycline 5, whereas two remaining patients achieved topical corticosteroids only (clobetasol, batametason) with success 6, 9. On the basis of our experience in treating patients with provoked BP, we have noticed that most of them required mild therapies containing clobetasol or tetracycline as the first‐line treatment. It is important in dialysed patients to avoid additional complications and side effects of immunosuppressive drugs.

Recently, it has been reported that BP may be associated with different internal disorders, particularly diabetes mellitus and neurodegenerative conditions. The relationship between BP and the latter was recently postulated as isophorms of the BP180 antigen observed in the postsynaptic areas in the brain are similar in structure to these BP180 antigens located in the BMZ of the skin. Based on this observation, it is speculated that neurodegenerative disorders may lead to the exposition of the isophorm of the BP180 to the immune system and the subsequent production of autoantibodies, which cross‐react with these in BMZ and are responsible for BP. In contrast to neurological disorders, the association of BP with renal insufficiency, renal transplantation or haemodialysis is not common. There are only several reports on this association in the literature 5, 6, 7, 8, 9. Although the pathogenic relationship between renal abnormalities and BP is not established, it is interesting that in some cases initial blisters typical of BP appeared on the skin of the forearm, where the fistula for haemodialysis was placed and closely related to the area of surgery, such as in our patient. It is possible that material used for fistula production may have allergenic properties, causing inflammation and blister formation. On the other hand, it appears likely that skin injury leading to fistula placement enabled the exposition of BP180 for the immune system, then the production of anti‐BMZ autoantibodies and, finally, the development of BP. Such a mechanism was also suggested in patients who developed BP after surgical procedures or UV radiation 11. It is important to note that the review of the literature and analysis of our case disclosed that none of the haemodialysed patients with BP required the removal or relocation of fistula. That is important to keep the patients with ESRD alive. In contrast, most of the described patients with chronic renal allograft rejection (CRAR) who developed BP did not respond to common therapy and finally required a nephrectomy to cure the skin lesions 10, 12, 13, 14, 15. That was probably because of the intolerance syndrome of the renal allograft (ISRA), a complication of CRAR. ISRAs rely on the production of autoantibodies generated during the renal rejection process, which cross‐react with the BMZ of the skin. It has also been suggested that immunological activity within the graft could be responsible for BP. In this cases, nephrectomy or atrophy of the graft are needed to clear cutaneous lesions completely, with no recurrence after the surgical removal. Therefore, one should be aware of that diversity as it may influence the therapy and prognosis in patients with renal insufficiency developing BP.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by a grant from the National Science Center, Poland (no. 2P05B 065 30). The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Lupi O, Rezende L, Zangrando M, Sessim M, Silveira CB, Sepulcri MA, Duarte DJ, Cardim P, Fernandes MM, Santos OR. Cutaneous manifestations in end‐stage renal disease. An Bras Dermatol 2011;86:319–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schmidt E, Zillikens D. Pemphigoid disease. Lancet 2013;381:320–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. van Beek N, Rentzsch K, Probst C, Komorowski L, Kasperkiewicz M, Fechner K, Bloecker IM, Zillikens D, Stöcker W, Schmidt E. Serological diagnosis of autoimmune bullous skin diseases: prospective comparison of the BIOCHIP mosaic‐based indirect immunofluorescence technique with the conventional multi‐step single test strategy. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2012;7:49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Taghipour K, Chi CC, Vincent A, Groves RW, Venning V, Wojnarowska F. The association of bullous pemphigoid with cerebrovascular disease and dementia: a case‐control study. Arch Dermatol 2010;146:1251–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Freeman BD, Rubin BG. Bullous pemphigoid after prosthetic vascular graft placement. Surgery 1997;124:112–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kamada N, Ino N, Hatamochi A, Shinkai H. A case of bullous pemphigoid in a patient on hemodialysis. J Dermatol 1998;25:246–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pardo J, Rodriguez‐Serna M, Mercader P, Fortea JM. Localized bullous pemphigoid overlying a fistula for hemodialysis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2004;51:S131–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Peruzzo J, Dias Pinheiro Dantas L, Zampese M. Bullous pemphigoid associated with chronic renal allograft rejection. J Am Acad Dermatol 2013;68:e192–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yesudian PD, Dobson CM, Ahmad R. Trauma‐induced bullous pemphigoid around venous access site in a haemodialysis patient. Clin Exp Dermatol 2002;27:70–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Devaux S, Michot C, Mourad G, Guillot B, Dereure O. Chronic renal graft rejection‐associated bullous pemphigoid: a cross‐reactive immune response? Acta Derm Venereol 2011;91:82–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Danescu S, Chiorean R, Macovei V, Sitaru C, Baican A. Role of physical factors in the pathogenesis of bullous pemphigoid: case report series and a comprehensive review of the published work. J Dermatol 2016;43:134–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rodriguez‐Caruncho C, Bielsa I, Bayes B, Guinovart R, Fernández‐Figueras T, Ferrándiz C. Bullous pemphigoid associated with chronic renal allograft rejection: resolution after transplantectomy. J Am Acad Dermatol 2011;65:e89–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tessari G, Barba A, Chieregato C, Tonini M, Boschiero L. Bullous eruption during chronic renal allograft rejection. Dermatology 2002;204:307–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yamazaki S, Yokozeki H, Katayama I, Komai R, Hashimoto T, Nishioka K. Childhood bullous pemphigoid associated with chronic renal allograft rejection. Br J Dermatol 1998;138:547–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Feehally J, Reilly DT, Walls J, Wood RF. An antibody‐mediated bullous skin eruption by chronic renal allograft rejection. Transplantation 1982;34:295–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]