Abstract

Skin tears are one of the most commonly treated wounds in the elderly population. In their most basic form, they are essentially traumatic random pattern flaps. We postulate that the injured blood flow to these skin flaps should be ignored and the tissue should be treated as a skin graft. A case report is presented of an 86‐year‐old female with an 8 × 3·5 cm skin tear to her right upper extremity after a hip fracture. In addition to conventional wound closure strips re‐approximating the tissues, a disposable negative pressure wound therapy device was placed to act as bolster. Upon its removal on day 5, the opposed skin tear tissue was found to be 100% viable. We therefore propose that this update may be an improvement over classical skin tear treatments and should be followed up with a case series.

Keywords: Negative pressure wound therapy, Random pattern flap, Skin graft, Skin tear, Wound treatment

Introduction

According to the International Skin Tear Advisory Panel (ISTAP), a skin tear (ST) is a wound caused by shear, friction and/or blunt force resulting in the separation of skin layers. An ST can be of either partial thickness (separation of the epidermis from the dermis) or full thickness (separation of both the epidermis and the dermis from the underlying structures). STs are most commonly seen in the elderly, critically ill/injured or in malnourished patients 1.

STs are highly variable in presentation, depending on depth, associated necrosis, infection, underlying haematoma and overall viable tissue surrounding the wound. Prevalence rates are as high as 21%, with some reports stating that STs occur more frequently than pressure ulcers 2, 3. The top three causes of STs are equipment injury, patient transfer and falls, with the leg or the arm being the most commonly affected location 1.

The two most commonly used grading systems of STs are the Payne–Martin Classification System (Table 1) for STs refined in 1993 4 and the Skin Tear Audit Research (STAR) Project (Table 2) created in 2007 5. Both of these are commonly used depending on the institution.

Table 1.

Payne–Martin classification of skin tears

| Category I – skin tear without tissue loss |

| Linear: epidermis and dermis are pulled apart |

| Flap: epidermal flap completely covers dermis with 1 mm of wound margin |

| Category II – skin tear with partial tissue loss |

| Scant tissue loss: <25% of the epidermal flap is lost |

| Moderate to large tissue loss: >25% of epidermal flap is lost |

| Category III – skin tear with complete tissue loss where epidermal flap is absent |

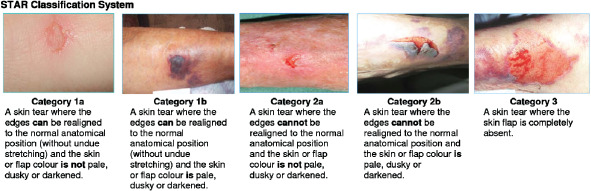

Table 2.

STAR classification system*

|

Skin Tear Adult Research (STAR). Silver Chain Nursing Association and School of Nursing and Midwifery, Curtin University of Technology. Revised 4 February 2010.

The goals of ST healing reflect those of standard wound management: reduce risk of infection, promote healing and obtain optimal cosmetic and functional outcomes 6. The three most commonly used methods in treating ST are (i) non‐adhesive dressing, (ii) steri‐strips and (iii) foam dressing 1. We are proposing a new method to treat STs using the backbone of what wound care management guidelines are based upon.

Case presentation

An 86‐year‐old female presented to the Emergency Department (ED) at Delray Medical Center after falling and suffering an intertrochanteric fracture of her right hip and traumatic ST to the right upper extremity. Her past medical history is significant for atrial fibrillation treated with Coumadin (Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Princeton, NJ) for the last 8 years.

The ST wound measured 8 cm long and 3·5 cm wide. Steri‐Strip™ skin closures (3M, St. Paul, MN) and a pressure dressing were placed over the wound by the ED staff and the patient was admitted to the orthopaedic service. The following day, the inpatient nursing staff was unable to control the bleeding through the bandage and the plastic surgeon was consulted. The wound (Figure 1) was treated with re‐application of strip closures to re‐approximate the skin edge (Figure 2). Upon achievement of satisfactory haemostasis, a reticulated open cell foam dressing (V.A.C.® Granufoam™ Dressing, KCI, San Antonio, TX) was placed superficially over a Mepitel® (Mölnlycke Health Care, Gothenburg, Sweden) interface dressing (Figure 3). Negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT, V.A.C.® Therapy™, KCI) was applied at −125 mmHg for 5 days. On day 5, the foam dressing was removed. Examination of the wound showed 100% survival of the ST as well as its complete fixation to the underlying bed (Figure 4).

Figure 1.

Skin tear (ST) on presentation to plastic surgeon (day 0).

Figure 2.

Skin tear (ST) treated with skin closure strips (day 0).

Figure 3.

Foam bolster dressing placed with 125 mmHg of negative pressure (day 0).

Figure 4.

100% uptake of avulsed skin tear (ST) to wound bed (day 5).

Discussion

STs in their most basic form are essentially traumatic random pattern flaps. The skin flaps associated with STs are almost universally composed of epidermis and, most often, little dermis. As a general rule of flap physiology, the tissue that is most distant from the blood supply is at the highest risk of necrosis. Added to this picture of traumatic insult to the tissues in an elderly patient, the likelihood of flap survival is further decreased.

Random pattern flaps are based on the subdermal vascular plexus of the skin. In the best of conditions, the maximum length‐to‐width ratio on the extremities should be 1:1 7. STs falling beyond this ratio should be an indicator to the treating practitioner that there is an inherent higher risk of failure.

Therefore, we postulated that we should ignore the random pattern flap component and treat STs as skin grafts. Although not a true skin graft because of the STs random pattern pedicle, we cannot depend on this traumatised blood supply to provide circulation to the distal edge of the flap. We, therefore, need to set the stage for these tissues to be assisted through plasmatic imbibition in the wound bed. It is this added step of NPWT that allows full skin flap survival in the face of certain partial or complete flap failure.

Unlike skin flaps, skin grafts are not bound to length‐to‐width ratios. Although, by design, they do need to be bolstered to their wound beds to avoid the accumulation of serosanguinous fluid that hampers the plasmatic imbibition of nutrients and oxygen diffusion in the wound bed. Even minimal fluid collection can result in graft failure.

In the elderly population in Southern Florida, the community standard of care for patients seen in the emergency departments of local hospitals, urgent care centres and physician offices is to re‐approximate the skin edges with skin closure strips and to cover with various supportive sterile dressings such as foams, petroleum‐based dressings such as Xeroform™ (Covidien LP, Mansfield, MA) or various non‐stick interface dressings such as Adaptic® (Systagenix, Gatwick, UK). All of these are performed with little or no regard for the elimination of skin flap shear or sub‐flap fluid formation. It is the author's experience that such classic methods, which solely rely on STs being treated as random pattern skin flaps, result in over 50% flap failure. These wounds then need to be treated by debridement and various dressing modalities for open wounds. This puts particular strain on elderly patients, who often have mobility issues that might require visiting nursing wound care as well as multiple visits to the wound surgeon for definitive management over the course of weeks to months depending on the size of the open area. The resulting high degree of morbidity for the elderly population and the cost for prolonged wound care, we believe, are unacceptable.

Instead of simply Steri‐Stripping the edges of the STs together, we believe that in Category I and beyond (using Payne–Martin Classification System) and Type Ib and beyond (using STAR classification), the health care provider should in addition apply NPWT to bolster the wound to prevent shear and fluid accumulation. A treatment time of 5–7 days is what we postulate adequate for most STs suffered by patients.

STs treated in the outpatient setting through the classical practice of frequent bandage changes performed by visiting nurses can be costly. The Medicare reimbursement alone for a homecare agency ‘episode of care’ can be as much as $2860·20 8. When adding practitioner and wound facility costs to this number, the need for a more economical solution becomes apparent. Potentially, disposable Prevena™ therapy at a cost of ∼$500 applied in an outpatient setting might alleviate the need for episodic home wound care and significantly reduce the costs.

Today, the wound surgeon has in his armamentarium disposable NPWT devices such as the Prevena™ Incision Management System (KCI), which is designed to be placed directly over closed incisions for up to 7 days. The incision management system is indicated to remove fluids and infectious materials from closed surgical incisions as well as to hold the wound edges together. This is very similar to the clinical scenario faced by providers when faced with a skin tear where wound edges need to be re‐approximated without allowance for fluid collection underneath. By applying the basic tenets of skin graft and random skin flap physiology to our re‐imagination of ST treatment, we believe we have found an improvement over classical thinking. We are presently conducting a case series to determine the outcomes, which we plan to publish in the near future as a follow‐up to this case report.

References

- 1. LeBlanc K, Baranoski S, Holloway S, Langemo D, Regan M. A descriptive cross‐sectional international study to explore current practices in the assessment, prevention and treatment of skin tears. Int Wound J 2014;11:424–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. LeBlanc K, Baranoski S, Skin Tear Consensus Panel Members . Skin tears: state of the science: consensus statements for the prevention, prediction, assessment, and treatment of skin tears. Adv Skin Wound Care 2011;24(9 Suppl):2–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. LeBlanc K, Baranoski S. Prevention and management of skin tears. Adv Skin Wound Care 2009;22:325–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Payne R, Martin ML. Defining and classifying skin tears: need for a common language. Ostomy Wound Manage 1993;39:16–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Carville K, Lewin G, Newall N, Haslehurst P, Michael R, Santamaria N, Roberts P. STAR: a consensus for skin tear classification. Prim Intent 2007;15:18–28. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vandervord JG, Tolerton SK, Campbell PA, Darke JM, Loch‐Wilkinson A‐MV. Acute management of skin tears: a change in practice pilot study. Int Wound J 2014; doi: 10.1111/iwj.12227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Clemens MW, Attinger CE. Functional reconstruction of the diabetic foot. Semin Plast Surg 2010;24:43–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services . Fact sheets: CMS announces payment changes for Medicare home health agencies for 2015. National Standardized 60 Day Episode Payment Rate, 30 October 2014.