Abstract

The purpose of this cross‐sectional study was to identify the prevalence of incontinence and incontinence‐associated dermatitis (IAD) in Australian acute care patients and to describe the products worn to manage incontinence, and those provided at the bedside for perineal skin care. Data on 376 inpatients were collected over 2 days at a major Australian teaching hospital. The mean age of the sample group was 62 years and 52% of the patients were male. The prevalence rate of incontinence was 24% (91/376). Urinary incontinence was significantly more prevalent in females (10%) than males (6%) (χ 2 = 4·458, df = 1, P = 0·035). IAD occurred in 10% (38/376) of the sample group, with 42% (38/91) of incontinent patients having IAD. Semi‐formed and liquid stool were associated with IAD (χ 2 = 5·520, df = 1, P = 0·027). Clinical indication of fungal infection was present in 32% (12/38) of patients with IAD. Absorbent disposable briefs were the most common incontinence aids used (80%, 70/91), with soap/water and disposable washcloths being the clean‐up products most commonly available (60%, 55/91) at the bedside. Further data are needed to validate this high prevalence. Studies that address prevention of IAD and the effectiveness of management strategies are also needed.

Keywords: Acute care, Cross‐sectional study, Incontinence, Incontinence‐associated dermatitis, Prevalence

Introduction

Incontinence‐associated dermatitis (IAD) is a complex, painful condition that is expensive and hard to treat 1, 2. It occurs in the perineum, labial folds, groin, upper thighs, buttocks, rectal area and gluteal cleft, as well as areas where there is increased friction between skin and clothing, or between skin and absorptive devices 3, 4. IAD is characterised by inflammation and erythema, which may present with blisters, erosion, denudation or serous exudate 2, 5. This results in high cost to the individual in terms of pain and suffering, increased morbidity, and increased length and cost of hospital stay 5.

Until recently, there was no international agreement on the name of the condition, its definition or its implications for clinical practice. However, in 2007, a seminal consensus document by Gray et al. 2 defined IAD as the response of the skin to chronic exposure to urine and faecal materials (inflammation and erythema with or without erosion or denudation). This definition acknowledges the source of the irritant, the response of the skin to that irritant and the fact that an area beyond the perineum is commonly affected. The standardised definition will allow researchers and clinicians to generate and compare data using a uniform conceptualisation of the condition.

Excess moisture on the skin acts as an irritant and contributes to skin breakdown and increased susceptibility to pressure injury from friction and shear 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7. Moisture‐damaged skin can be vulnerable to secondary infection with Candida albicans or coliform bacteria 3. Wearing an absorptive containment product (pad) causes occlusion, resulting in increased (more alkaline) baseline skin pH, increased moisture from perspiration and compromised skin barrier function 2, 8. The alkaline pH of urine promotes activity of the digestive enzyme lipases and proteinases in faeces, which in turn makes keratin in the stratum corneum vulnerable to breakdown 3. Wet skin is less resistant to injury from friction, and is at increased risk of erosion from rubbing on bed linens or incontinence pads 3, 8, 9. Exposure to both faeces and urine is more damaging to skin than exposure to urine alone 10.

Identification of IAD is based on skin inspection and accurate differentiation between other skin lesions, particularly pressure injury. Studies indicate that the differential diagnosis between a pressure ulcer and IAD is difficult, with IAD often being misclassified by nurses as a pressure injury 1, 11. In fact, the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP) recommends that the stage II pressure injury category should not be used to describe skin tears, tape burns, perineal dermatitis, maceration or excoriation 12. IAD also needs to be differentiated from intertriginous dermatitis, a moisture‐associated skin injury resulting from trapped moisture and friction in skin folds 1, 3, 6, 13. IAD has further been confused with fungal or bacterial infections as well as other dermatological conditions 14. Misclassification of these lesions can result in poor patient outcomes as well as in inappropriate and ineffective use of health care resources 15. The primary goal of prevention and treatment of IAD is to minimise skin exposure to irritants 3.

Understanding IAD requires an appreciation of incontinence, a condition associated with significant morbidity, decreased quality of life, as well as being a burden for care givers and the health care system. Urinary incontinence is an involuntary leakage of urine 16, and while no consensus definition exists for faecal incontinence, its generally accepted definition is the involuntary loss of solid or liquid stool 17. Incontinence occurs more often in older adults, although it can affect any age group 9, 18. Further, faecal incontinence is the second leading cause of admission to long‐term care in the USA 19.

Prevalence of incontinence among patients in the acute care setting is estimated to range from 10% to 37% 9, 18, 20. Incontinence in the critical care environment ranges from 12% to 30% 21, 22 and in the long‐term acute care settings, it is 22% for urinary incontinence and 57% for faecal incontinence 23. Limited data exists with regard to identification of the scope of incontinence or demographic variables associated with incontinence in the Australian acute care setting.

IAD also presents challenges in the acute care setting where the prevalence ranges from 20% to 50% 8, 9, 22, 23, 24. The prevalence of IAD in adults in Australian acute care hospitals is not known. Prospective Australian data are needed to provide insights into the scope of both incontinence and IAD in the acute care setting to aid health care providers in the development of prevention and management strategies.

Aims

The purpose of this study was to explore incontinence and IAD in the Australian acute care hospital setting. Specific research aims were to:

Identify the prevalence of incontinence (urine and faecal).

Identify the prevalence of IAD.

Describe the products worn to manage incontinence and the products provided at the bedside for perineal skin care.

Methods

Study design

A cross‐sectional study design was used.

Study setting and sample

This study was conducted at a 929‐bed major acute care teaching hospital in southeast Queensland, Australia. The facility provides acute care over a comprehensive range of specialities including medicine, surgery, orthopaedics, oncology, obstetrics, gynaecology, intensive care, burns and trauma. It is the largest tertiary referral hospital in Queensland, providing care to almost 94 000 inpatients in 2012 25.

Hospitalised adults aged ≥18 years admitted to the facility were eligible for inclusion. Patients were surveyed from Internal Medicine, Surgery, Critical Care [which includes a 36‐bed intensive care unit (ICU) and an 18‐bed transit ward attached to the emergency department], Cancer Care and Women's and Newborns' (only adults were surveyed from this service) admitting services. Patients from maternity and mental health services were excluded from the study.

Operational definitions

Incontinence is the inability to control the flow of urine and/or stool any time in the preceding 24 hours 9. Patients with indwelling urinary catheters were deemed continent of urine for the analysis. The presence of a urinary catheter prevents urine from coming into contact with skin, and therefore removes the source of irritation (urine) necessary for the development of IAD. Patients with faecal containment devices were deemed incontinent of faeces because of the high likelihood of faecal leakage from the containment device resulting in faecal contact with skin. These categorisations are consistent with previous studies 9, 26.

IAD is the presence of any skin redness with or without erosion caused by skin contact with urine and/or faeces (rather than other sources of moisture) on the buttocks, coccyx, rectal area, scrotum, labia, lower abdomen, upper thighs, gluteal cleft or groins in an incontinent patient 2.

Fungal infection is the clinical presentation of a central maculopapular rash with characteristic satellite lesions in patients with IAD 3, 27. No microbiological testing was performed to confirm the presence of a fungal infection in this study. This is consistent with current clinical practice, as well as a previous IAD study 9. Diagnosis of superficial fungal infection relies more heavily on clinical findings and less on laboratory support 28, 29.

Pressure injuries are a localised injury to the skin and/or underlying tissue, usually over a bony prominence, as a result of pressure, or pressure in combination with shear 12. Pressure injuries were staged according to the Australian pressure injury staging guidelines at the time of data collection 30.

Measures

Continence status and products

Continence status, incontinence containment, clean‐up and skin protection products as well as demographic data were recorded on a data collection instrument that was designed by the principal investigator (JC), based on a literature review. The instrument was pilot tested by ten registered nurses at the research site and the face validity established. Minor changes were made to the wording and layout of the continence section of the tool based on feedback from the pilot group. Demographic data on age, gender and admitting service were collected.

Stool quality assessment

Stool quality was measured based on the Bristol Stool form scale, but collapsed into dichotomas variables: formed, which equates to type 1–4 on the Bristol Stool form scale, and semiformed‐liquid, which equates to type 5–7 31.

IAD severity

IAD severity was measured by clinicians, using the skin assessment tool (SAT) 32. This tool does not require the patient to report symptoms 5, 6, nor does it assess pain. The SAT was designed to derive a cumulative IAD severity score, with a numerical score assigned according to severity within each of three categories: skin redness, area of skin breakdown (cm2) and erosion. A cumulative severity score (maximum score = 10) is the sum of the scores for the three categories. It has good inter‐rater reliability [κ = 0·81 95% confidence interval (CI), 0·69–0·87] 33. Word descriptors were assigned to match numerical severity categories. Numerical cut‐off points for each category were determined by consensus from a panel of experts comprising the authors and three wound care clinicians with 40 years of combined experience in the specialty. The cut‐off points are 0 = no IAD, 1–3 = mild IAD, 4–6 = moderate IAD, 7–9 = severe IAD and 10 = extreme IAD.

Procedures

Prior to data collection, all research assistants (RAs) (n = 30; 28 RNs, an occupational therapist and a medical practitioner) were trained in identification of IAD, pressure injury and fungal infection. Inter‐rater reliability was established at the conclusion of the education session by scores on a multiple‐choice test of clinical photographs of a variety of IAD lesions, pressure injuries and fungal infections. The test required participants to differentiate between IAD, pressure injury and a fungal infection as well as to classify the IAD images according to the study instrument. A score of 80% was required for the RA to participate in the study. The method of using photographs to test inter‐rater reliability has previously been used 11, 34, 35. RAs were also trained in study procedures.

This study was conducted over two consecutive days in November 2011 by the principal investigator (JC) and 30 RAs. Skin inspections were conducted by the RAs on all eligible, consenting patients. The incontinence management product the patient was wearing was recorded. Each patient's buttocks, coccyx, rectal area, scrotum, labia, lower abdomen, upper thighs, gluteal cleft and groins were inspected and loss of skin integrity classified as IAD, pressure injury or clinical indication of fungal infection. Continence data were collected and for those who were incontinent, data regarding type of incontinence were obtained from the patient, primary nurse and/or clinical records. Stool quality and frequency data for faecally incontinent patients were obtained from the patient, primary nurse and/or clinical records. Data were also recorded on the type of incontinence clean‐up and skin protection products provided at the bedside. When patients were absent from the ward at the time of data collection, the RAs returned and included those present when possible. Demographic data were collected on all patients. To ensure accuracy, the principal investigator who is a skin integrity expert conducted an independent pelvic girdle inspection on all cases identified by the RAs as having IAD and validated the SAT score.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committees for both the research site and the university. Written information about the study was distributed to all eligible patients the day prior to data collection. Patients provided verbal consent as required by the Human Research Ethics Committees.

Statistical methods

Participants were assigned a study number and all data were de‐identified. Data were entered into Statistical Packages for Social Sciences (SPSS) (Version 20·0, Armonk, NY). A random 10% of data entry was crosschecked for accuracy. Incomplete data were coded as missing data.

Descriptive statistics were used to describe study variables (means and standard deviations for continuous variables; frequencies and percentages for categorical variables). Prevalence of incontinence was calculated by the total number of incontinent patients in the sample divided by the total number of study patients. Prevalence of IAD was calculated by the total number of IAD cases in the sample divided by the total number of study participants. Prevalence of IAD among incontinent patients was calculated by the total number of IAD cases divided by the total number of incontinent participants. Bivariate analysis using descriptive correlational statistics (χ 2 test for independence with Yates continuity correction and Fisher's exact test where expected cell counts were less than five) was used to explore characteristics of the sample with incontinence and IAD. P values less than 0·05 were considered statistically significant. Direct logistic regression analysis was performed to find out whether independent variables – gender, admitting service and age – predict the outcome, incontinence. The variables entered into the model were based on what is known about incontinence, in particular, association with increasing age, association with being female and the prevalence of geriatric syndromes, specifically, incontinence in medical patients 18. In addition, selection of these independent variables facilitates comparison of our results with other studies, providing clinical applicability. The Hosmer–Lemeshow test was used to examine the goodness of fit of the logistic regression model.

Results

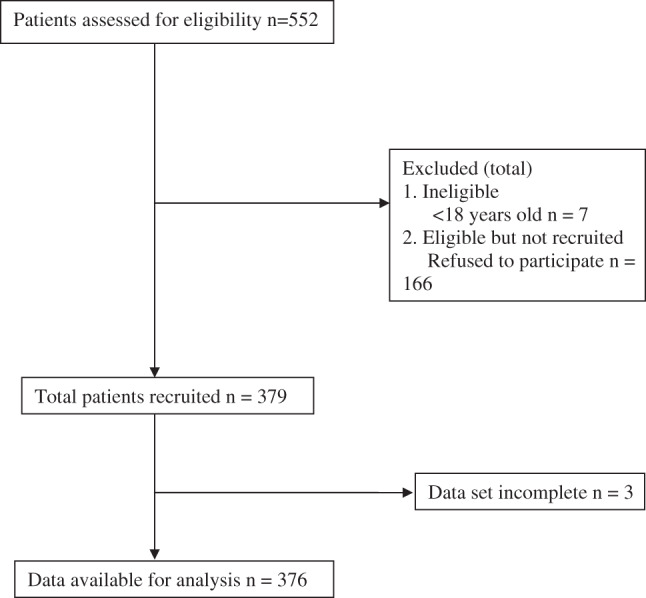

Of the 552 patients assessed for eligibility (Table 1), 545 patients were found to be eligible; 379 patients consented to take part and were surveyed. Data for 376 patients were included in the analysis (Figure 1). Three patients were excluded from the analysis, as the screening tool was not completed. The mean age of the sample was 62 (SD 19·3) years and 52% (n = 194) of patients were male. Patients were admitted most often to the Internal Medicine (44%, n = 167) and Surgical services (39%, n = 146) (Table 2). The Hosmer–Lemeshow test was used to examine the goodness of fit of the logistic regression model. The result was non‐significant, χ 2 (8) = 3·03, P = 0·932, indicating that the model fit was satisfactory.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients assessed for eligibility (n = 552)

| Admitting service | Male number (%) | Female number (%) | Patients assessed for eligibility | Age (mean) | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internal Medicine | 100 (46·3) | 116 (53·7) | 216 | 68·2 | 17·2 |

| Surgical services | 140 (65·4) | 74 (34·6) | 214 | 55·5 | 19·4 |

| Cancer Care | 39 (58·2) | 28 (41·8) | 67 | 61·3 | 17·8 |

| Critical Care (includes Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine) | 19 (47·5) | 21 (52·5) | 40 | 48·8 | 19·3 |

| Women's and Newborns'a | 0 (0) | 15 (100) | 15 | 50·4 | 18·4 |

| Total | 298 | 254 | 552 | 56·8 | 22·7 |

Only adults were evaluated from this admitting service.

Figure 1.

Patient recruitment and participant diagram.

Table 2.

Sample characteristics

| Sample n = 376 | Incontinent patients n = 91 | Patients with IAD n = 38 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean, standard deviation) | 62 (19·3) | 70 (17·4) | 74·8 (15·3) |

| Gender, number (%) | |||

| Male | 194 (51·6) | 41 (45) | 13 (34·2) |

| Female | 182 (48·4) | 50 (54·9) | 25 (65·8) |

| Indwelling urinary catheter present (number, %) | 49 (13) | 23 (25·3) | 9 (23·7) |

| Admitting service, number (%) | |||

| Internal Medicine | 167 (44·4) | 55 (60·4) | 23 (60·5) |

| Surgical services | 146 (38·8) | 21 (23·1) | 8 (1·1) |

| Critical Care (includes Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine) | 21 (7·7) | 6 (6·6) | 3 (7·9) |

| Cancer Care | 29 (7·7) | 6 (6·6) | 2 (5·3) |

| Women's and Newborns'a | 13 (3·5) | 3 (3·3) | 2 (5·3) |

IAD, incontinence‐associated dermatitis.

Only adults were evaluated from this admitting service.

Prevalence of incontinence

The prevalence of incontinence was 24% (91/376) (Table 2). Double incontinence (urinary and faecal) was most common (12%, 46/376), followed by faecal incontinence (8%, 32/279), while the prevalence of urinary incontinence alone was 3·5% (13/376). Urinary catheters were present in 13% (49/376) of patients. Faecal incontinence was more prevalent in females (11%, 43/376) than in males (9%, 35/376). Urinary incontinence was significantly more prevalent in females (10%) than in males (6%) (χ 2 = 4·458, df = 1, P = 0·035); however, the reason for urinary catheter placement was not determined by this study, so the prevalence of urinary incontinence may have been underestimated. Direct logistic regression was performed to assess the impact of a number of factors on incontinence. The model contained three independent variables (age, gender and admitting service). The full model containing all predictors was statistically significant, χ 2 (6, N = 376) = 31·48, P < 0·001. Gender made no difference to the odds of a patient having incontinence [odds ratio (OR) = 0·85, P = 0·516; Table 3]. Older patients had a greater likelihood of having incontinence compared with younger patients (OR = 1·03, P < 0·001). Patients in the Surgical admitting service were less likely to have incontinence, compared with patients in the Internal Medicine admitting service (OR = 0·51, P = 0·029). Internal Medicine and other admitting services showed no difference in the likelihood of patients having incontinence (P > 0·05, Table 3).

Table 3.

Predictors of incontinence (n = 376)

| Characteristics and intercept | Coefficient β | Standard Error | Wald chi‐square | P value | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −2·750 | 0·617 | 19·226 | <0·001 | 0·067 | |

| Gender (Ref: female) | ||||||

| Male | −0·168 | 0·259 | 0·421 | 0·516 | 0·85 | (0·51, 1·4) |

| Age | 0·029 | 0·008 | 13·610 | <0·001 | 1·03 | (1·01, 1·05) |

| Admitting service (Ref: Internal Medicine) | ||||||

| Critical Care | 0·272 | 0·537 | 0·257 | 0·612 | 1·31 | (0·46, 3·76) |

| Surgery | −0·670 | 0·308 | 4·745 | 0·029 | 0·51 | (0·28, 0·94) |

| Cancer Care | −0·508 | 0·496 | 1·048 | 0·306 | 0·60 | (0·23, 1·59) |

| Women's and Newborns' a | −0·189 | 0·712 | 0·070 | 0·791 | 0·83 | (0·2, 3·34) |

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Only adults were evaluated from this admitting service.

Prevalence of IAD

IAD was present in 10% (38/376) of the sample and the prevalence of IAD in those who were incontinent was 42% (38/91) (Table 2). Among incontinent patients, χ 2 analysis showed that there was no significant association between type of incontinence (urinary versus faecal) and IAD (χ 2 = 7·237, df = 1, P = 0·007). Among patients with IAD, χ 2 analysis showed that patients with semi‐formed or liquid stool were more likely to have IAD than those with formed stool (χ 2 = 5·520, df = 1, P = 0·027). Faecal frequency and IAD were not significantly associated (χ 2 = 3·536, df = 1, P = 0·116) (Table 4). Mild skin redness was present in 84% (32/38) of patients with IAD, a small area of skin breakdown occurred in 32% (12/38), mild erosion was present in 32% (12/38) of patients, while 50% (19/38) of patients had no erosion. The most common anatomical locations for skin injury were the buttocks (42%, 16/38), followed by the rectal area (34%, 13/38). The SAT severity score showed that 82% (31/38) were suffering from mild IAD, 13% (5/38) were suffering from moderate IAD, 6% (2/38) were suffering from severe IAD and no patients were suffering from extreme IAD (Table 5).

Table 4.

Clinical characteristics of incontinent patients (n = 91) and patients with IAD (n = 38)

| Variable | Incontinent patients n = 91 | Patients with IAD n = 38 |

|---|---|---|

| Urinary incontinence | ||

| Male, number (%) | 6 (6·6) | 1(2·6) |

| Female, number (%) | 7 (7·8) | 0 (0) |

| Faecal incontinence | ||

| Male, number (%) | 18 (19·8) | 5 (13·1) |

| Female, number (%) | 14 (15·4) | 10 (26·3) |

| Double (urine and faecal) incontinence | ||

| Male | 17 (18·7) | 7 (18·4) |

| Female | 29 (31·9)a | 15 (39·5)a |

| Faecal quality number (%) | ||

| Formed | 5 (5·5) | 0 (0) |

| Semi‐formed or liquid | 36 (39·6) | 19 (50) |

| Missing | 50 (54·9) | 19 (50) |

| Faecal frequency, number (%) | ||

| <3 days | 13 (14·3) | 5 (13·2) |

| ≥3 per day | 28 (30·8) | 17 (44·7) |

| Missing | 50 (54·9) | 16 (42·1) |

IAD, incontinence‐associated dermatitis.

Percentages may not add up to 100 because of rounding.

Table 5.

Characteristics, location and severity of IAD (n = 38)

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Skin redness | ||

| Mild | 32 | 84·2 |

| Moderate | 4 | 10·5 |

| Severe | 2 | 5·3 |

| Area of skin breakdown | ||

| None | 19 | 50·0 |

| Small | 13 | 34·2 |

| Moderate | 2 | 5·3 |

| Large | 4 | 10·5 |

| Skin erosion | ||

| None | 19 | 50·0 |

| Mild | 18 | 47·4 |

| Moderate | 1 | 2·6 |

| Severe | 0 | 0 |

| Extreme | 0 | 0 |

| Area affecteda | ||

| Buttocks | 16 | 42·1 |

| Coccyx | 5 | 13·2 |

| Gluteal cleft | 4 | 10·5 |

| Groins | 6 | 15·8 |

| Lower abdomen | 3 | 7·9 |

| Rectal | 13 | 34·2 |

| Scrotum/labia | 7 | 18·4 |

| Upper thighs | 2 | 5·3 |

| IAD severity score | ||

| 1–3 mild IAD | 31 | 81·6 |

| 4–6 moderate IAD | 5 | 13·1 |

| 7–9 severe IAD | 2 | 5·3 |

| >9 extreme IAD | 0 | 0 |

| Pressure injury | 8 | 21·1 |

| Clinical indication of fungal infection | 12 | 31·6 |

IAD, incontinence‐associated dermatitis.

Total >100% as patients may have more than one area affected.

Clinical indication of fungal infection was present in 32% (12/38) of patients with IAD. However, the presence of fungal infection may have been over‐ or under‐estimated, as no microbiological testing to confirm the diagnosis of fungal infection was undertaken in this study. Pressure injuries were present in 6% (22/376) of patients, with 21% (8/38) of patients with IAD having a pressure injury (Table 5).

Products worn to manage incontinence and products used to provide perineal skin care.

Wrap around and pull up briefs (i.e. those aids worn as an alternative to underwear) were worn by 77% (70/91) of incontinent patients at the time of evaluation (Table 6). Soap/water and disposable washcloths were the most common incontinence clean‐up products at the bedside for incontinent patients (60%, 55/91). Moisturising agents were present at the bedside in 34% (31/91) of incontinent patients. Skin protection products were present at the bedside in 57% (52/91) patients. Examples of these products are 3M™ Cavilon™ No Sting Barrier Film (3M, Saint Paul, MN) and Skin Basics™ Zinc and Castor Oil Cream (Biotech Pharmaceuticals, Victoria, Australia).

Table 6.

Products worn to manage incontinence and products used to provide perineal skin care (n = 91)

| Variable | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Incontinent aid worn | ||

| Urinary incontinence | ||

| None | 2 | 2·2 |

| Wrap‐around pad | 4 | 4·4 |

| Pull‐up pad | 5 | 5·5 |

| Insert pad | 1 | 1·1 |

| Faecal incontinence | ||

| None | 11 | 12·1 |

| Wrap‐around pad | 10 | 11·0 |

| Pull‐up pad | 8 | 8·8 |

| Insert pad | 1 | 1·1 |

| Double incontinence | ||

| None | 1 | 1·1 |

| Wrap‐around pad | 21 | 23·1 |

| Pull‐up pad | 22 | 24·2 |

| Insert pad | 1 | 1·1 |

| Incontinent aid missing | 4 | 4·4a |

| Incontinence clean‐up | ||

| Soap/water and disposable cloth | 55 | 60·4 |

| Missing | 36 | 39·6 |

| Moisturiser | ||

| Yes | 31 | 34·1 |

| No | 22 | 24·2 |

| Missing | 38 | 41·7 |

| Skin protection products | ||

| Yes | 52 | 57·1 |

| Missing | 39 | 42·8a |

Percentages may not add up to 100 because of rounding

Discussion

Incontinence occurred in one in four patients hospitalised in a major acute care setting in Australia, indicating that it is a common and serious problem. IAD occurs in 42% of those who are incontinent, demonstrating that IAD is a prevalent and under‐appreciated skin injury in hospitalised patients. The most common incontinence aid worn was an incontinent brief (77%), with soap/water and disposable cloths being the most common incontinence clean‐up products present at the bedside (60%). This is the first Australian study to report the prevalence of both incontinence and IAD in the acute care setting and to differentiate IAD from pressure injury and fungal infection.

Incontinence‐associated dermatitis

Acute care patients are subjected to treatment regimes that may result in IAD, for example, antibiotics, changes in dietary intake and enteral feeds. Thus, acute care patients are a unique population that are at increased risk. IAD has been under‐appreciated as it is not the primary reason for admission. Anecdotal evidence suggests that it is not only accepted, but also actually expected that older patients will be incontinent.

IAD prevalence data for the general acute care setting is limited. The majority of published data are drawn from specialised settings such as critical care or the aged care setting. A study in three urban hospital critical care units found an IAD prevalence of 36% 36 and prevalence in a long‐term acute care setting was 23% 23. Prevalence of IAD in aged care ranges from 6% to 22% 10, 37.

An important finding that emerged from our study is that liquid and semi‐formed stool was more associated with IAD compared with formed stool. No other published studies have examined the association between stool quality and IAD. Congruent with our finding, the extensive review by Gray et al. 8 implicates stool as an aetiological factor in IAD, with clinical experience strongly suggesting that liquid stool is more irritating than solid or formed stool. Further research is warranted to determine if stool quality, particularly semi‐formed/liquid stool, promotes the development of IAD.

Most IAD severity in our study was mild (82%, 31/38). Junkin and Selekof 9 classified IAD as red and dry skin, red and weepy skin or the presence of blisters in the areas likely to be exposed to urine or faeces. Of the patients with IAD, 75% (18/24) had red and dry skin, with 25% (6/24) having red and weepy skin. Both of these categories could be interpreted as being at the less severe end of a severity continuum, which correlates with the severity of IAD in our study. The natural history of IAD is poorly understood 2, but progression from ‘mild’ through to ‘severe’ IAD is inevitable in the presence of persisting incontinence, inadequate management of incontinence and inadequate or inappropriate incontinence clean‐up, skin protection and treatment of any secondary cutaneous infections. Early recognition and treatment is thus of optimum importance.

IAD needs to be differentiated from other skin lesions, especially in the pelvic girdle. Pressure injuries have historically been confused with IAD. The NPUAP and the European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (EPUAP) have specifically stated that IAD is not a pressure injury 12. A strength of this study is that both IAD and pressure injury were identified, so prevalence of each could be accurately determined. Future pressure injury prevalence studies would benefit from additionally measuring incontinence and IAD.

Presence of urine and faeces on denuded skin creates a favourable environment for the development of fungal infection, with fungal infection commonly reported as a potential complication of IAD 2, 7, 27. The presence of a secondary fungal infection needs to be differentiated from IAD. In our study, the presence of fungal infection was determined based on clinical presentation of a central maculopapular rash with characteristic satellite lesions 3. No quantitative microbiological testing was undertaken. According to Professor Jack Sobel (personal email, jsobel@med.wayne.edu, 3 April 2014), the fungal rash may also present as non‐specific, confluent and papular, creating some difficulty in clinical diagnosis. The presence of a secondary fungal infection would require treatment, but it is desirable to obtain a microbiological culture prior to commencing anti‐mycotic therapy 28, 29, 38 Accordingly, the presence of a secondary fungal infection may have been under‐ or over‐estimated in our study. Our data showed that 32% (12/38) of patients with IAD demonstrated clinical evidence of a fungal infection. This is higher than the US data from Junkin and Selekof 9, which showed that 10% of incontinent patients had a fungal rash (based on clinical examination). The higher prevalence of suspected fungal infection in our study may be associated with the higher IAD prevalence rate. These infections are a serious threat to patient outcomes because of the possibility of under‐diagnosis or missed diagnosis, and the potential for delay in treatment. It is not clear whether a fungal infection has an aetiological role in IAD, or whether it is only a secondary infection.

Pressure injuries were present in 6% of our entire sample, with 12% of incontinent patients having a pressure injury. This prevalence is lower than that reported by Junkin and Selekof 9 where 22% of incontinent patients had a pressure injury. In part, our lower pressure injury rate may reflect the increased emphasis on pressure injury prevention in recent years.

One of the issues in the literature continues to be the lack of a universal definition for IAD prevalence. That is to say, should the denominator be the entire sample, or only those with incontinence? Since IAD cannot occur without incontinence (i.e. skin exposure to urine and/or faeces) 2, the number of incontinent patients would logically be the denominator. Most studies report IAD prevalence with the denominator being the number of incontinent patients 9, 22, 33, but a consistent standard needs to be established. However, we recommend that until a standard definition is accepted, researchers present the IAD rate for the entire sample and for those who are incontinent to ensure clarity and accuracy. We have used that approach in this article.

Incontinence

The definition of incontinence for an IAD prevalence study needs further clarification, specifically, how to categorise patients who have a urinary catheter. The presence of a urinary catheter prevents skin exposure to urine – a known cause of IAD. Previous studies have categorised patients with urinary catheters as continent 9, 26. However, it should be acknowledged that categorising patients with a urinary catheter as continent can result in an underestimation of incontinence prevalence. In the acute care setting, patients can be catheterised for a multitude of reasons including incontinence. For example, in this study 11 of 15 patients surveyed in the ICU had a urinary catheter. The use of a urinary catheter in the ICU is essential to monitor kidney function and fluid balance in the critically ill.

Our data show a significant association between increasing age and incontinence. Junkin and Selekof 9 found that the odds of older patients having incontinence were greater (OR 4·979, 95% CI 1·015–22·427). Incontinence is recognised as one of the geriatric syndromes 18, 39 and has been associated with a longer length of hospital stay and a greater risk of being discharged to a residential care setting 40, 41, 42. Ageing of the global population 43 coupled with the rising cost of health care 43, 44, 45 means that managing incontinence in the acute care setting is an ever‐increasing challenge.

It is noteworthy that the prospective prevalence data for incontinence in the acute care setting in Australia are limited, even though incontinence is associated with significant morbidity and decreased quality of life 39. Health care providers require an understanding of the magnitude of a condition to provide appropriate care. We are not certain why the probability of incontinence is lower in the Surgical admitting service than in the Internal Medicine admitting service, although there is some evidence supporting the increased prevalence of geriatric syndromes (including incontinence) in older medical patients in an acute care setting 18. Our study adds important results that could provide a better understanding of the burden of incontinence in the Australian acute care setting.

Products worn to manage incontinence and products used to provide perineal skin care

Our study showed that disposable incontinence briefs were the most common incontinence aids worn (77%), that soap/water and disposable washcloths were the most common clean‐up products at the bedside (60%), and that skin barrier protection was available at the bedside of 57% of patients. A consistent, structured approach to the prevention and treatment of IAD is required 2, 3. Having supplies at the bedside is an efficient approach and ensures that a consistent strategy is used. Three steps are recommended: (i) gentle cleansing, using a soft disposable washcloth and cleansers without perfumes or irritants and close‐to‐skin pH (a no‐rinse formulation is suggested); (ii) moisturisation to preserve the lipid barrier 3; and (iii) application of a skin barrier product is required to protect the stratum corneum from moisture and irritants 3, 6. Lack of bedside supplies suggests that there is a gap between available products/recommendations and care. Further research is needed to identify how products are used as well as how effective they are in preventing and treating IAD.

Limitations

Several limitations need to be noted. This was a cross‐sectional study and no cause and effect can be inferred. Every effort was made to recruit eligible participants; however, direct clinical examination of patients in this type of study can be intrusive and may have limited enrolment (in our study this was 69%). Data as to why patients refused to participate was not recorded. This study did not have ethical approval to collect data from the patients who did not consent. The IAD Severity Assessment tool was chosen to classify severity of the condition. However, this scale does not include a measure of patient pain. IAD and faecal quality analysis was conducted at a bivariate level as the amount of missing data in these variables made adjusting for confounders and logistic regression analysis unfeasible. Clinical inspection was used to determine the presence of fungal infection. The prevalence of fungal infection may have been over‐ or under‐estimated as no quantitative laboratory measurement was used to confirm the diagnosis. Future research needs to use appropriate quantitative measures to confirm the presence of fungal infection.

Conclusion

This is the first Australian study to report the prevalence of both incontinence and IAD in the acute care setting and to differentiate IAD from pressure injury and fungal infection. Almost one quarter of hospitalised adults were incontinent, and of the incontinent patients in the study, more than 40% developed IAD. Faecal incontinence occurred more often than urinary incontinence. Liquid and semi‐formed stool was more significantly associated with IAD compared with formed stool. In addition, our data confirmed that the likelihood of incontinence increases with age, especially in those >80 years of age. Products for incontinence containment, clean‐up, and skin protection need to be available at the bedside to facilitate incontinence management. Further, prospective observational prevalence studies are essential to confirm these data in hospitalised Australian adults. The availability of results informing the prevalence of both incontinence and IAD is essential to measure the scope of the problem. More research addressing the effectiveness of treatment of incontinence and IAD in the acute care setting is needed. Additional research examining the aetiology of IAD, and the role of fungal infections in IAD is warranted.

Acknowledgements

The principal investigator is the recipient of a Royal Brisbane and Women's Hospital Research Postgraduate scholarship, which in part supported preparation of this manuscript. We thank the patients who participated in this study and the RAs who collected data. We also thank the Director of the RBWH Quality and Safety Unit—Therese Lee, as well as Michelle Holland, Kelly McDonough and Katrina Rooke for the ‘in kind’ and logistical support of this project. We acknowledge the valuable contribution of Nurse Practitioner Complex Wound Management, Kerrie Coleman and Clinical Nurse Skin Integrity, Kathleen Hocking for their clinical expertise and review of the instrument. Finally, we would like to thank Emeritus Professor Nancy Stotts for reviewing this paper.

References

- 1. Doughty D, Junkin J, Kurz P, Selekof J, Gray M, Fader M, Bliss DM, Beeckman D, Logan S. Incontinence‐associated dermatitis: consensus statements, evidence‐based guidelines for prevention and treatment, and current challenges. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2012;39:303–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gray M, Bliss DZ, Doughty DB, Ermer‐Seltun J, Kennedy‐Evans KL, Palmer MH. Incontinence‐associated dermatitis: a consensus. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2007;34:45–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Black JM, Gray M, Bliss DZ, Kennedy‐Evans KL, Logan S, Baharestani MM, Colwell JC, Goldberg M, Ratcliff CR. MASD part 2: incontinence‐associated dermatitis and intertriginous dermatitis: a consensus. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2011;38:359–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gray M. Optimal management of incontinence‐associated dermatitis in the elderly. Am J Clin Dermatol 2010;11:201–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Junkin J, Selekof J. Beyond "diaper rash": incontinence‐associated dermatitis: does it have you seeing red? Nursing 2008;38(11 Suppl):56hn1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gray M. Incontinence‐related skin damage: essential knowledge. Ostomy Wound Manage 2007;53:28–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gray M, Black JM, Baharestani MM, Bliss DZ, Colwell JC, Goldberg M, Kennedy‐Evans KL, Logan S, Ratcliff CR. Moisture‐associated skin damage: overview and pathophysiology. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2011;38:233–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gray M, Beeckman D, Bliss DZ, Fader M, Logan S, Junkin J, Selekof J, Doughty D, Kurz P. Incontinence‐associated dermatitis: a comprehensive review and update. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2012;39:61–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Junkin J, Selekof J. Prevalence of incontinence and associated skin injury in the acute care inpatient. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2007;34:260–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bliss DZ, Savik K, Harms S, Fan Q, Wyman JF. Prevalence and correlates of perineal dermatitis in nursing home residents. Nurs Res 2006;55:243–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Beeckman D, Schoonhoven L, Boucque H, Van Maele G, Defloor T. Pressure ulcers: e‐learning to improve classification by nurses and nursing students. J Clin Nurs 2008;17:1697–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel and European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel . Prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers: clinical practice guigeline. Washington, DC: National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bliss DZ, Powers J. Faecal incontinence and its associated problems in hospitalised patients: the need for nursing management. WCET J 2011;31:35–9. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Farage MA, Miller KW, Elsner P, Maibach HI. Structural characteristics of the aging skin: a review. Cutan Ocul Toxicol 2007;26:343–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Beeckman D, Schoonhoven L, Verhaeghe S, Heyneman A, Defloor T. Prevention and treatment of incontinence‐associated dermatitis: literature review. J Adv Nurs 2009;65:1141–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Abrams P, Blaivas JG, Stanton SL, Andersen JT. Standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function. NeurourolUrodyn 1988;7:403–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Halland M, Talley NJ. Fecal incontinence: mechanisms and management. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2012;28:57–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lakhan P, Jones M, Wilson A, Courtney M, Hirdes J, Gray LC. A prospective cohort study of geriatric syndromes among older medical patients admitted to acute care hospitals. J Am Geriatri Soc 2011;59:2001–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Beitz JM. Fecal incontinence in acutely and critically ill patients: options in management. Ostomy Wound Manage 2006;52 56–8, 60, 2–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ostaszkiewicz J, O'Connell B, Millar L. Incontinence: managed or mismanaged in hospital settings? Int J Nurs Pract 2008;14:495–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bliss DZ, Johnson S, Savik K, Clabots CR, Gerding DN. Fecal incontinence in hospitalized patients who are acutely ill. Nurs Res 2000;49:101–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Driver DS. Perineal dermatitis in critical care patients. Crit Care Nurse 2007;27:42–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Arnold‐Long M, Reed L, Dunning K, Ying J. Incontinence‐associated dermatitis (IAD) in a long‐term acute care (LTAC) facility: findings from a 12 week prospective study. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2011;38(3S):S7–S. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bliss DZ, Johnson S, Savik K, Clabots CR, Gerding DN. Fecal incontinence in hospitalized patients who are acutely ill. Nurs Res 2000;49:101–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Royal Brisbane and Women's Hospital Marketing and Communications . 2011–2012 RBWH year in review. Brisbane: Metro North Hospital and Health Service Royal Brisbane and Women's Hospital, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Halfens RJG, Meesterberends E, van Nie‐Visser NC, Lohrmann C, Schönherr S, Meijers JMM, Hahn S, Vangelooven C, Schols J. International prevalence measurement of care problems: results. J Advanced Nurs 2013;69:e5–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zulkowski K. Diagnosing and treating moisture‐associated skin damage. Adv Skin Wound Care 2012;25:231–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Maertens JA. Diagnosis of fungal infections. New York: Informa Healthcare, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Richardson MD. Fungal infection diagnosis and management Chichester. Wiley‐Blackwell: West Sussex, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Australian Wound Management Association . Clinical practice guidelines for the prediction and prevention of pressure ulcers, 1st edn. West Leederville: Cambridge Publishing, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lewis SJ, Heaton KW. Stool form scale as a useful guide to intestinal transit time. Scand J Gastroenterol 1997;32:920–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kennedy K, Lutz J, editors. Comparison of the efficacy and cost effectiveness of three skin protectants in the management of incontinent dermatitis. In: European Conference on Advances in Wound Management; 1996 Oct 4th; Amsterdam, the Netherlands, 1996.

- 33. Beeckman D, Verhaeghe S, Defloor T, Schoonhoven L, Vanderwee K. A 3‐in‐1 perineal care washcloth impregnated with dimethicone 3% versus water and pH neutral soap to prevent and treat incontinence‐associated dermatitis: a randomized, controlled clinical trial. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2011;38:627–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Defloor T, Schoonhoven L. Inter‐rater reliability of the EPUAP pressure ulcer classification system using photographs. J Clin Nurs 2004;13:952–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Beeckman D, Schoonhoven L, Fletcher J, Furtado K, Gunningberg L, Heyman H, Lindholm C, Paquay L, Verdu J, Defloor T. EPUAP classification system for pressure ulcers: European reliability study. J Adv Nurs 2007;60:682–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bliss DZ, Savik K, Thorson MAL, Ehman SJ, Lebak K, Beilman G. Incontinence‐associated dermatitis in critically ill adults: time to development, severity, and risk factors. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2011;38:433–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Beeckman D, Vanderwee K, Demarre L, Paquay L, Van Hecke A, Defloor T. Pressure ulcer prevention: development and psychometric validation of a knowledge assessment instrument. Int J Nurs Stud 2010;47:399–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Vazquez JA, Sobel JD. Mucosal candidiasis. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2002;16:793–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Inouye SK, Studenski S, Tinetti ME, Kuchel GA. Geriatric syndromes: clinical, research, and policy implications of a core geriatric concept. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007;55:780–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chiarelli P, Bower W, Wilson A, Attia J, Sibbritt D. Estimating the prevalence of urinary and faecal incontinence in Australia: systematic review. Aust J Ageing 2005;24:19–27. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fonda D, Nickless R, Roth R. A prospective study of the incidence of urinary incontinence in an acute care teaching hospital and its implications on future service development. Aust Clin Rev 1988;8:102–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Green JP, Smoker I, Ho MT, Moore KH. Urinary incontinence in subacute care – a retrospective analysis of clinical outcomes and costs. Med J Aust 2003;178:550–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kinsella K, He W. An Aging World: 2008, International Population Reports,. U. S. Census Bureau, 2009. Contract No.: P95/09‐1.

- 44.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). Health expenditure Australia 2010–11 Canberra: AIHW; 2012. [WWW document]. URL http://www.aihw.gov.au/WorkArea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=10737423003 [accessed on 20 June 2013].

- 45. Rak S, Coffin J. Affordable care act. J Med Pract Manage 2013;28:317–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]