Abstract

To identify the risk factors associated with the development of skin tears in older persons four hundred and fifty three patients (151 cases and 302 controls) were enrolled in a case–control study in a 500‐bed metropolitan tertiary hospital in Western Australia between December 2008 and June 2009. Case eligibility was defined by a skin tear on admission, which had occurred in the last 5 days; or, a skin tear developed during hospitalisation. For each case, two controls who did not have a skin tear and had been admitted within 1 day of the case, were also enrolled. Data collected from the nursing staff and inpatient medical records included characteristics known, or hypothesised, to be associated with increased vulnerability to skin tears. Data analysis included a series of multivariate stepwise regressions to identify a number of different potential explanatory models. The most parsimonious model for predicting skin tear development comprised six variables: ecchymosis (bruising); senile purpura; haematoma; evidence of a previously healed skin tear; oedema; and inability to reposition oneself independently. The ability of these six characteristics to predict who among older patients could subsequently develop a skin tear now needs to be determined by a prospective study.

Keywords: Case control, Risk assessment, Skin tears

Introduction

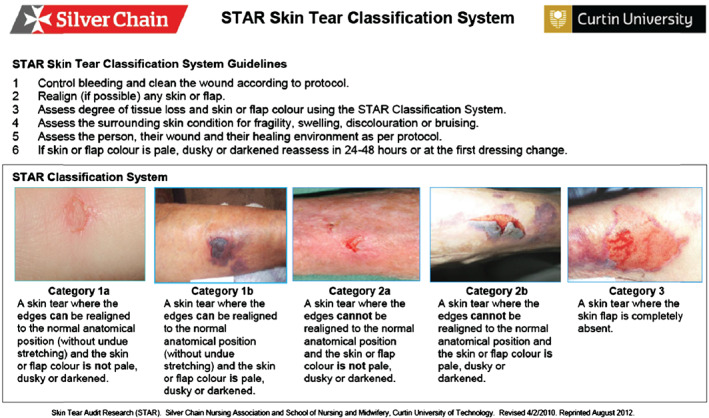

Skin tears are among the most common wounds found in older health care consumers 1. Skin tears were identified as the third most prevalent wound in public hospitals in Western Australia in four surveys conducted between 2007 and 2011 2. The 2011 survey reported a prevalence of 9·6%, with 24% of these tears assessed as Category 3 (total skin loss) according to the STAR Skin Tear Classification 3. Moreover, 57% of the skin tears identified were hospital acquired 2.

Facility acquired skin tears can have an impact on several parameters: financially, as they require nursing time to clean and dress (time that would need to be diverted from other tasks) as well as the cost that will be incurred to procure wound care products to treat; emotionally, as they are often painful and unsightly; and physically, as on occasion they can develop into chronic wounds, particularly if on the lower leg of an individual with venous insufficiency 3.

The high prevalence of skin tears among older people has been related to the pathophysiological changes that occur in ageing skin, the increased incidence of falls among this cohort and their increased requirement of manual handling 3, 4, 5. Other risk factors are visual impairment, impaired mobility or balance, altered mental status and the use of certain medications such as corticosteroids or anticoagulants 3, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13. A 24‐item skin integrity risk assessment form piloted with 26 residents of a nursing home was an early attempt to develop a tool, but details of its reliability and validity are lacking 4.

Recently, consensus statements and guidelines on skin tear prevention and management have been published, despite the lack of systematic reviews or randomised clinical trials 14. More robust research on skin tears is required to confirm the identified potential risk factors, to examine their influence and interdependence and to inform the development of prevention strategies 1.

Study aim

This study aimed to identify the characteristics of older people that were strongly associated with an increased risk of developing a skin tear.

Methods

Study design

A non‐matched case–control study design was used to allow simultaneous investigation of multiple aetiologic factors. As an initial attempt, this is particularly advantageous to identify the causal and preventative factors for a disease about which very little is known 15.

Setting/population

The study was conducted in a 500‐bed metropolitan tertiary hospital in Western Australia. Based on discussions with the nursing management as to the average length of stay in different wards and in which wards skin tears had been identified as more prevalent, it was decided that the study would be conducted in all wards except the short stay and psychiatric wards.

Sample size

The sample comprised 151 cases and 302 controls. This enabled detection of an odds ratio of two (for any risk factor) with a power of 86% assuming that 20% of controls were exposed to the same risk factor(s). A significance level of 5% was used.

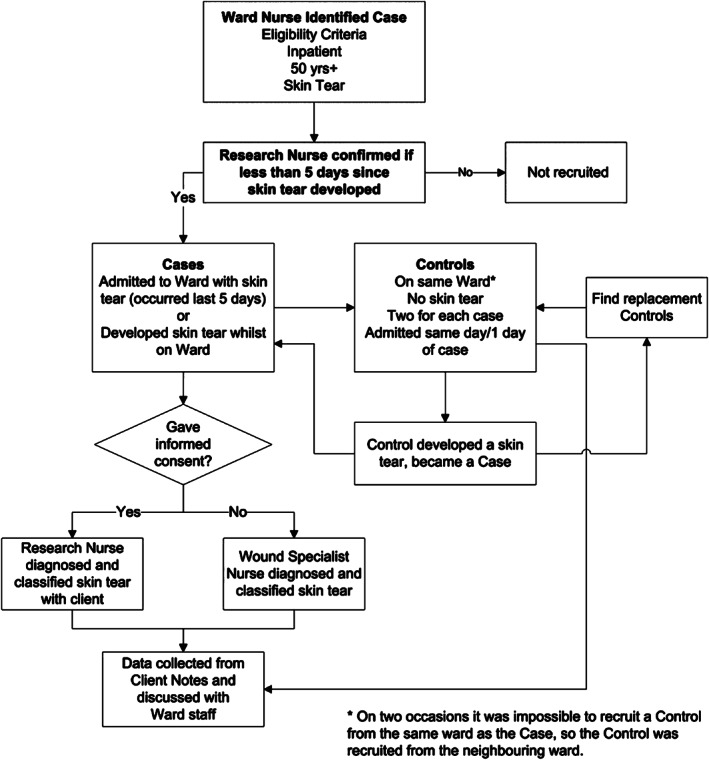

Research and recruitment process

Figure 1 depicts the process used to identify and enrol cases and controls and also includes details of eligibility criteria as well of those who were subsequently removed from the trial as they did not meet the inclusion criteria or who were recruited as controls and then developed skin tears and, therefore, became cases.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of recruitment process.

Patient eligibility and enrolment

Case eligibility was defined as age 50 or above and having a skin tear that was either present on admission (and <5 days old) or that occurred during hospitalisation.

Control eligibility was defined as age 50 or above, admission within 1 day of the case, and not having a skin tear either on admission or during hospitalisation. Eligibility was restricted to individuals 50 years of age or older because of the well‐established association between advancing age and skin tear development 1, 2, 5, 10, 13.

The enrolment process for the study was developed in consultation with the staff from participating wards as it involved a member of the ward staff identifying when a patient met the case eligibility criteria and whether they would, on the basis of their cognitive status, be able to give informed consent. This could have been at admission; during the skin inspection process, which forms part of the routine admission assessment; or later in their stay during personal or nursing care. These patients were then referred to the Research Nurse to complete the consent formalities. Concurrently, the Research Nurse identified other patients in the ward who were eligible to be the controls. When more than two patients were eligible, they were selected for enrolment on the basis of the alphabetical order of their surname. If there were no suitable controls in the same ward as the case, suitable individuals in the ward that was situated nearest to the original ward were enrolled.

Data collection and measures

Patients enrolled as a case had their wound inspected to confirm that it was a skin tear, either by the Research Nurse or Hospital Wound Specialist, both of whom had been trained in the assessment and classification of skin tears. If the wound was confirmed as a skin tear, it was classified using the STAR skin tear classification system 3.

Information about the cause of the wound was collected directly from the patients or from the inpatient medical record. All other data for the cases as well as the controls were collected directly from the inpatient medical record or from the ward staff by the Research Nurse. These data were recorded on a standard paper‐based form adapted from a tool previously developed in 2007 as part of a skin tear incidence study at a Victorian acute care facility (unpublished). Data collected on the form included all characteristics known, or hypothesised, to be associated with increased vulnerability to skin tears, such as age, medical history, current physical condition and treatment; plus the scores from a small number of validated tools measuring characteristics again having been shown, or anecdotally believed, to have an aetiological relationship with skin tears. These tools were the Charlson Comorbidity Index 16; the Braden Pressure Risk Assessment 17; the Mini Mental State Examination Score (MMSE) 18 or Abbreviated Mental Test Score (AMTS) 19; and, the Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA®) 20. Anatomical location of the wound was recorded on a diagram of the body (both front and back being portrayed separately).

Data were collected on weekdays, usually within 1 day of a patient being enrolled in the study. In the event of a control developing a skin tear subsequently, they became a case and three new controls were identified (a replacement for them as a control plus the usual two controls per case).

Data management and analysis

Data were double‐entered into a study database, cleaned and analysed using Stata Version 10 (Stata Corporation 2005, College Station, Texas, USA) and SAS Version 9.1. (SAS Institute Inc., 2002–2004, Cary, NC.) Descriptive statistics were used to summarise the characteristics of the two populations. The characteristics of cases and controls were then compared using Pearson χ 2 tests for the categorical data and student t‐tests for the continuous variables. An explanatory logistic model for skin tears was developed, which balanced parsimony (complexity) with near optimal explanation of variance, as per the Shtatland method 21 that uses the Akaike information criterion (AIC) and Schwarz information criterion (SC) to determine this.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committees of the health and aged care organisation where the researchers had their substantive positions, the university that auspiced the research, as well as the tertiary hospital where the research was undertaken.

Results

There were 151 patients with skin tears enrolled as cases. The causes and location of skin tears are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Place of origin, cause and anatomical location of cases' skin tears

| Variable | Number (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Place where the skin tear was developed | Hospital | 107 (71%) |

| Home | 44 (29%) | |

| Primary cause | Knock | 40 (26·5%) |

| Fall | 39 (25·8%) | |

| During equipment use | 20 (13·3%) | |

| Unknown | 8 (5·3%) | |

| Transfer | 7 (4·6%) | |

| Lost balance | 7 (4·6%) | |

| Other less common causes | 30 (19·9%) | |

| Anatomical location | Arm | 69 (45·8%) |

| Leg | 47 (31·1%) | |

| Hand/wrist | 22 (14·6%) | |

| Trunk | 5 (3·3%) | |

| Foot/ankle | 4 (2·6%) | |

| Head | 4 (2·6%) |

Three hundred and two patients were enrolled as controls, of whom seven subsequently developed a skin tear during hospitalisation and were reenrolled as cases. Table 2 shows the potential risk factors that were found to have a significant association (P < 0·05) with skin tears in a series of univariate logistic analyses. Other factors examined that were not found to have a significant association in this study (P > 0·05) were gender, admission type, smoking, Charlson Comorbidity Score, cardiovascular disease, congestive heart failure, uncomplicated diabetes, vision or hearing impairment, polypharmacy, corticosteroids and sedatives.

Table 2.

Characteristics significantly associated with skin tears in univariate analysis

| Characteristic | Cases N = 151 | Controls N = 302 | Odds ratio (CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 80 years | 74 years | 1·06 (1·04–1·08) | <0·0001 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 37·1% | 25·8% | 1·69 (1·11–2·57) | 0·0138 |

| Dementia diagnosis | 9·9% | 17·2% | 1·89 (1·07–3·32) | 0·0281 |

| Cognitive impairment assessed | 28·5% | 17·2% | 0·52 (0·32–0·83) | 0·0060 |

| Diabetic complications | 20·5% | 9·9% | 2·22 (1·25–3·94) | 0·0065 |

| Malignant lymphoma | 6·0% | 2·0% | 3·13 (1·09–8·95) | 0·0337 |

| Myocardial infarction | 36·4% | 25·8% | 1·65 (1·08–2·50) | 0·0201 |

| Vascular disease other | 10·9% | 22·5% | 2·37 (1·40–4·01) | 0·0013 |

| Senile purpura | 74·2% | 23·2% | 0·10 (0·07–0·17)* | <0·0001 |

| Ecchymosis | 64·9% | 8·9% | 0·05 (0·03–0·09)* | <0·0001 |

| Haematoma | 70·2% | 30·6% | 0·18 (0·12–0·29)* | <0·0001 |

| Paper‐thin skin | 86·1% | 45·0% | 0·13 (0·08–0·22)* | <0·0001 |

| Healed skin tear | 48·3% | 6·3% | 0·07 (0·04–0·13)* | <0·0001 |

| Wrinkly, furrowed loose skin | 83·4% | 60·9% | 0·30 (0·19–0·50)* | <0·0001 |

| Dry skin | 74·8% | 52·6% | 0·37 (0·24–0·57)* | <0·0001 |

| Bulla | 11·9% | 4·6% | 0·35 (0·17–0·74)* | <0·0001 |

| Oedema | 37/7% | 16·9% | 0·33 (0·22–0·52)* | <0·0001 |

| Macerated | 6·6% | 1·7% | 0·23 (0·08–0·71)* | 0·0099 |

| Able to reposition | 31·8% | 60·9% | 3·34 (2·21–5·06)* | <0·0001 |

| Contractures | 4·0% | 0·7% | 0·16 (0·03–0·81) | 0·0265 |

| Dark skin | 7·9% | 2·0% | 0·23 (0·07–0·77) | 0·0181 |

CI, confidence interval.

Effect of No versus Yes.

The multivariate logistic regression model that ‘best’ balanced statistical performance with model complexity contained six variables (Table 3). It showed that the risk of skin tears increased between two‐ and six‐fold in the presence of ecchymosis, previously healed skin tear, senile purpura, oedema, haematoma and inability to reposition independently.

Table 3.

Risk factors associated with skin tears in a hospitalised sample of older adults

| Characteristic | Odds ratio | Confidence limits 95% | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ecchymosis (Yes versus No) | 6·241 | 3·243 | 12·011 |

| Healed skin tear (Yes versus No) | 5·416 | 2·709 | 10·829 |

| Senile purpura (Yes versus No) | 2·657 | 1·466 | 4·814 |

| Oedema (Yes versus No) | 3·011 | 1·617 | 5·605 |

| Able to reposition independently (No versus Yes) | 2·307 | 1·317 | 4·041 |

| Haematoma (Yes versus No) | 2·259 | 1·296 | 3·938 |

Discussion

This study has proposed a simple model to explain skin tear development using six variables: four that describe characteristics of the individual's skin; the fifth, oedema, that directly affects the skin; and the sixth, the inability to independently reposition, which reflects the physical status of the person and the need for frequent handling. In a number of earlier publications 1, 4, 5, 10, 13, 22, 23, five of the six have been identified previously to be associated with skin tears, or as potential risk factors for their development.

The four variables that describe skin characteristics were senile purpura, ecchymosis (bruising), haematoma and evidence of a previously healed skin tear. Senile purpura was described by White et al. (1994) as appearing when ‘the blood vessels become thinner and more fragile, leading to the appearances of haemorrhaging known as senile purpura’ 4 and as a potential risk factor for skin tear development because the bleeding under the epidermis enables the skin to lift more easily when friction is applied, thus resulting in a skin tear 23. This same mechanism may be responsible for the association between ecchymosis and the development of a skin tear. However, although bruising is frequently noted at the site of skin tears 1, 4, 10, 13, 22, it may well have been caused at the same time as the skin tear and its potential usefulness as a predictor of risk could be considered doubtful. This applies similarly to haematoma, the only characteristic in the model that has not been previously identified as a potential risk factor for skin tear in the literature. A haematoma is usually defined as a collection of blood or a clot within the tissues, flap or realigned skin (Figure 2). Haematomas have often been observed at the site of a skin tear 24 and it was the anticipated effect of a haematoma on the viability of the skin flap or realigned skin that resulted in the addition of haematoma to the STAR Classification system. It would appear logical to suggest that in situations when a haematoma exists independently of a skin tear, the skin tightness resulting from haematoma formation may make the skin more vulnerable to breakdown from any further trauma. As with ecchymosis, it is the temporal relationship between the skin characteristics and the development of the skin tear that will determine whether it will be useful in predicting the development of a skin tear at some point in the future. This can only be tested with the help of a prospective study.

Figure 2.

STAR classification system.

Once damaged, a wound never fully recovers all its original tensile strength despite being healed 25. As a result of the slow replenishment of epidermal cells, which is an inevitable physiological change associated with skin as one ages, it will take longer to repair a skin tear 1. Both of these effects may explain why a previously healed skin tear plays an important role in our model and why they have been previously identified as potential risk factors by a number of authors 4, 5, 10, 13, 23, 26, 27.Given the strength of the association found in this study and the localised nature of any vulnerability related to the site of a previous skin tear, an alternative explanation may be that evidence of previous skin tears simply indicates that a person's skin is particularly susceptible to tearing and/or that because of their own or others' behaviour their skin is subject to more frequent trauma.

Oedema, the fifth physical characteristic in our model, has also been previously identified as a skin tear risk factor 4, 13 because it affects the epidermal skin barrier and results in reduced resistance to external forces and hence results in increased vulnerability to skin tear development 28.

The final characteristic in our model, the inability to reposition independently, has again been identified by other researchers 9, 27. The mechanism suggested here is that in vulnerable individuals, exposure to repeated manual handling to assist in repositioning increases the potential of trauma to the skin.

All the items included in our data collection tool had either been previously found to be associated with, or proposed to be, risk factors for skin tears. A large proportion, as shown in Table 1, was found to have a significant association with having a skin tear when looked at individually and, as such, confirmed the findings from earlier studies. However, many of these risk factors, such as having dementia, complicated diabetes or vascular disease, did not contribute independently to our explanatory model when we used multivariate analysis that controlled for confounding. Perhaps, the most surprising of these was age, given its strong univariate association as well as the frequency of its citation in the literature as a risk factor for skin tear development because of the physiological changes to the skin that occurs with ageing. However, it is likely that its effect disappeared because of the inclusion of the skin characteristics that more directly reflected the effect of ageing on the skin.

Also somewhat surprising was the finding that there was no significant association between having a skin tear and any of the medication variables, despite polypharmacy, anti‐coagulants, strong analgesia and corticosteroids often being cited as risk factors 3, 14, 29.

Limitations and further research

It is acknowledged that the data collection methods could have introduced bias as, for pragmatic reasons, the Research Nurse was not blinded to whether the patient was a case or control. However, as the data collection method was standardised through the use of a tool, we believe that the lack of blinding was unlikely to have led to bias.

Another potential limitation may have been the quality of documentation in the inpatient medical records. Lack of attention to detail and accuracy is known anecdotally to occur when the condition is unrelated to the reason for admission.

This was a study of hospitalised patients and it is therefore impossible to know how well these risk factors can be generalised to non‐hospitalised patients who sustain skin tears.

A further limitation is one that has already been discussed in relation to two of the variables in the risk model we developed. Because the study is retrospective and we collected the data after the event it was not always possible to distinguish the temporal relationship between the factor being measured and the outcome that was studied. This is a limitation of all case control studies and the reason why they are used to generate hypotheses rather than to provide definitive answers as to causality. This study was designed to generate a risk model that could be used as the basis of a risk assessment tool that could then be tested prospectively. Work is currently in progress to develop a tool that will reliably assess the presence of the six characteristics in our model. Once developed, its ability to correctly predict who develops a skin tear in a hospital setting will be tested in a prospective cohort study.

Conclusion

Although skin tears are common wounds among older adults, there has been little rigorous research on related risk factors and no risk assessment tools have been developed. This study sought to address that gap by identifying a risk model for skin tear development, which can be used to develop a risk assessment tool. The ‘best’ model that has been identified includes six factors: four skin characteristics, oedema and the ability to reposition independently. All of the attributes, apart from haematoma, have been identified as potential risk factors in previous literature. In the next stage of the study we will develop a tool that can reliably assess the presence of the six characteristics and test its ability to accurately predict who develops a skin tear.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded jointly by the School of Nursing and Midwifery, Curtin University, Western Australia and the Office of the Chief Nursing Officer, WA Health.

The authors would like to acknowledge the support and assistance of Anne Nield, Donna Angel, Jan Wright, Robyn Kovac, Gavin Leslie and Tabatha Rando, without whose help the project would not have run so smoothly.

References

- 1. Ratcliffe CR, Fletcher KR. Skin tears: a review of the evidence to support prevention and treatment. Ostomy Wound Manage 2007;53:32–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mulligan S, Prentice J, Scott L. WoundsWest wound prevalence survey 2011 state‐wide overview report. Perth, WA: Department of Health, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Carville K, Lewin G, Newall N, Haslehurst P, Michael R, Santamaria N, Roberts P. STAR: a consensus for skin tear classification. Prim Inten 2007;15:18–28. [Google Scholar]

- 4. White M, Karam S, Cowell B. Skin tears in frail elders: a practical approach to prevention. Geriatr Nurs 1994;15:95–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Edwards H, Gaskill D, Nash R. Treating skin tears in nursing home residents: a pilot study comparing four types of dressings. Int J Nurs Pract 1998;4:25–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Baranoski S. Skin tears: guard against this enemy of frail skin. Nurs Manage 2001;32:25–32. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bryant R, Rolstad B. Examining threats to skin integrity. Ostomy Wound Manage 2001;47:18–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Calliano C. Skin care: keeping the outside healthy. Nursing 2002;32(6 supplement):1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Everett S, Powell T. Skin tears – the underestimated wound. Prim Inten 1994;2:8–30. [Google Scholar]

- 10. McGough‐Csamy J, Kopac C. Skin tears in institutionalized elderly: an epidemiological study. Ostomy Wound Manage 1998;44(3A):14S–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. White M. Skin tears: a descriptive study of the opinions, clinical practice and knowledge base of RNs caring for the aged in high care residential facilities. Prim Inten 2001;9:138–49. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Meuleneire F. Wound care. The management of skin tears. Nurs Times 2003;99:69–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Morey P. Skin tears: a literature review. Prim Inten 2007;15:122–9. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Holmes R, Davidson M, Thompson B, Kelechi T. Skin tears: care and management of the older adult at home. Home Healthc Nurse 2013;31:90–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hennekens C, Buring J. Case–control studies. In: Mayrent S, editor. Epidemiology in medicine, Ist edn. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins, 1987:132–45. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Charlson M, Pompei P, Ales A, Mackenzie C. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bergstrom N, Braden B, Laguzza A, Holman V. The Braden scale for predicting pressure sore risk. Nurs Res 1987;36:205–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Folstein M, Folstein S, McHugh P. Mini‐mental state. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975;12:189–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hodkinson H. Evaluation of a mental test score for assessment of mental impairment in the elderly. Age Ageing 1972;1:233–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nestle Nutrition Institute . MNA® Mini Nutritional Assessment. URL http://www.mna‐elderly.com/default.html [accessed on 5 May 2015].

- 21. Shtatland S, Cain E, Barton M. The perils of stepwise logistic regression and how to escape them using information criteria and the output delivery system SAS Global Forum 26. Long Beach, California; 2001. URL http://www2.sas.com/proceedings/sugi26/p222‐26.pdf [accessed 6 May 2015].

- 22. Payne R, Martin M. Defining and classifying skin tears:Need for a common language. A critique and revision of the Payne‐Martin classification system for skin tears. Ostomy Wound Manage 1993;39:16–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cuzzell J. Clues: bruised, torn skin. Am J Nurs 1990;90:16–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Stephen‐Haynes J, Carville K. Skin tears made easy. Wounds Int 2011;2:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Simon P. Skin wound healing In: Meyers D. eMedicine: Medscape. WebMD LLC, New York; 2014. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/884594‐overview#aw2aab6b6 [accessed 5 May 2015]. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Payne R, Martin M. The epidemiology and management of skin tears in older adults. Ostomy Wound Manage 1990;26:26–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. LeBlanc K, Baranoski S. Skin tears: state of the science: consensus statements for the prevention, prediction, assessment, and treatment of skin tears. Adv Skin Wound Care 2011;24:2–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Voegeli D. Basic essentials: why elderly skin requires special treatment. Nurs Resident Care 2010;12:422–9. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Voegeli D. Understanding the main principles of skin care in older adults. Nurs Stand 2012;27:59–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]