Abstract

The purpose of the article is to evaluate the acellular dermis' utility in reconstructing full‐thickness defects after scar contracture releasing and giant nevus resection. From the year 2012 to 2014, 18 consecutive patients underwent composite graft (thin autograft and alloderma) transplantation. Among these patients, 16 patients suffered from burned scar contracture in the upper extremities, and two young cases were met with giant nevus on the upper extremity. Ten of 13 adult cases with upper extremity scar affection were chosen for a comparative study. Twenty hands were randomly allocated into group A and group B. The thick autograft was used to repair one upper extremity in group B, and the composite grafts were used to cover the other upper extremity in group A. Besides appraisal of the recipient sites' function and aesthetics, donor sites were also estimated after a mean of 12 months' follow‐up through the Vancouver Scar Score Scale. After evaluation in the above comparative study through the Vancouver Score Scale, in the recipient evaluation, no statistical difference was found in the pigmentation score between two groups, while statistical difference was achieved in other aspects (vascularity, pliability, height). In the donor site's evaluation, statistical difference was established between the two groups in all facets. One adult patient was dissatisfied with the hypertrophic scar on the donor site, and about almost a half of the area became a hypertrophic scar in the recipient site. No atrophic change occurred; one little girl, suffering from large nevus, was operated on by removing nearly the whole giant nevus on the upper limb. Unfortunately, she presented with finger tip necrosis occurring. The finger tip was not ultimately preserved and was repaired with an abdomen flap. Acellular dermal matrix is an excellent option and a useful tool for reconstructing large full‐thickness skin defects after releasing burned scar contracture and removing giant nevus. With thin‐skin graft meshed, a donor site's presentation brings courage to patients, while recipient sites can reach nearly the same elasticity and function compared to thick‐grafted skin.

Keywords: Acellular dermis, Thick graft, Thin graft

Introduction

Full‐thickness skin defects are frequently followed by burn contracture release, larger tumour resection and other traumatic events. The aims are rapid wound closure and then encouraging functional and cosmetic outcomes. To improve outcome in reconstructive operations, a thick‐skin graft's utility may be the optimal choice because it carries more dermis than a thin‐skin graft and is thus supposed to be affected less by scar recurrence. However, the use of thick‐ or full‐thickness skin grafts is not always available because of the donor site's morbidity and delayed healing. The non‐immunogenic dermal matrix, which are removed cells of the dermis and epidermis, maintaining the structural and biochemical integrity, has served as a substitute to replace and augment a part of grafted skin in co‐graft techniques and has gained better scar function and appearance on recipient sites. Since its first introduction, its utility in reconstructing tissue defects has been recognised by surgeons. Especially in young patients group, their guardians expect excellent results not only on the recipient sites but also the donor sites. An extra evident scar is not accepted on the donor sites in most paediatric cases. It has been proved that when an autograft and allograft are combined in covering defects, the alloderma plays an important role in the growth of vessels and fibroblasts, which facilitates the survival of the autograft at a later stage post‐operation. Thus, it confers on the neodermis the role of bridge and property of augmentative product.

As a popular solution in reconstructing tissue defects, many reports have been presented, including burned wounds, breast surgery, tumour resection and scar contracture. Among these reports, scar contracture and giant nevus were recruited in our study. Although advancement has been achieved in previous reports about recipient sites, no study about patients' donor sites are presented. We made a retrospective intergroup control study of donor sites' scarring and recipient sites' function and cosmetics.

Patients and methods

Between 2012 and 2014, 18 consecutive patients were included in the series. Among these patients, 16 patients suffered from burned scar contracture in the upper extremity. Two young cases were met with a large nevus on the upper extremity. Ten adult patients with upper extremity scar affection were chosen for a comparative study. The thick autograft was used to repair one upper extremity in group B, and the composite grafts (thin skin graft and alloderma) were used to cover the other upper extremity in group A. They were informed previously to observe the ultimate comparative outcome. The thin median autograft was harvested from the back, thigh or scalp areas. The co‐graft was transferred simultaneously without two‐stage of operations. After an average 1‐year follow‐up, the evaluation of donor sites and recipient sites was accomplished. Patients' demographics are shown in Table 1. No statistical difference was achieved in the average defect size between the two groups preoperatively as shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

Patients passive range of motion at the affected sites

| Patient | Sex | Age (year) | Affected sites | Preoperative PROM | Postoperative PROM | Composite graft or autograft |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 30 | Left Forearm and hand back(wrist motion) | 20 | 70 | Composite graft |

| 2 | M | 13 | Elbow | – | – | Composite graft |

| 3 | F | 40 | I, II, III, IV, V, palm of Right hand | 20 | 50 | Autograft |

| Left Elbow | 70 | 110 | Composite graft | |||

| 4 | F | 33 | Right hand back and forearm (wrist motion) | 10 | 50 | Autograft |

| Left hand back and forearm (wrist motion) | 20 | 45 | Composite graft | |||

| 5 | M | 41 | I, II, III, IV, V and right hand back | 40 | 90 | Composite graft |

| Left hand back and forearm (wrist motion) | 40 | 90 | Composite graft | |||

| 6 | F | 11 | II, III, IV, MCP of Right hand | 0 | 60 | Composite graft |

| Left hand back and forearm (wrist motion) | – | – | – | |||

| 7 | M | 2 | Left forearm | – | – | Composite graft |

| Right forearm | – | – | Composite graft | |||

| 8 | F | 35 | I, III, IV, V, MCP of right hand and hand back | 30 | 90 | Autograft |

| II, III, IV of Left hand and forearm | 30 | 80 | Composite graft | |||

| 9 | F | 27 | II, IV, V, MCP of left hand and hand back | 0 | 35 | Autograft |

| I, II, III of Right hand | 0 | 40 | Composite graft | |||

| 10 | M | 31 | I, II, IV, V of left hand | 30 | 85 | Composite graft |

| Right hand back and forearm | 20 | 80 | Autograft | |||

| 11 | F | 44 | I, V, MCP of right hand | 20 | 65 | Autograft |

| II, III, V of Left hand | 35 | 70 | Composite graft | |||

| 12 | M | 37 | Left elbow | 50 | 95 | Autograft |

| Right elbow and forearm | 40 | 90 | Composite graft | |||

| 13 | F | 35 | I, II, III, IV, V of left hand | 25 | 65 | Composite graft |

| I, III, IV, MCP of right hand | 10 | 40 | Autograft | |||

| 14 | M | 23 | Right elbow and forearm | 35 | 80 | Composite graft |

| II, III, IV of Left hand | 20 | 70 | Autograft | |||

| 15 | M | 26 | I, II, IV, V, MCP of right hand | 10 | 60 | Composite graft |

| II, V, MCP of left and forearm | 15 | 50 | Autograft | |||

| 16 | F | 3 | Left arm large nevus | – | – | Composite graft |

| 17 | F | 15 | Right arm large nevus | – | – | Composite graft |

| 18 | F | 2 | Bilateral forearms | – | – | Composite graft |

I, thumb; II, index finger; III, middle finger; IV, ring finger; V, small finger; MCP, metacarpophalangeal ; PROM, passive range of motion.

Table 2.

Comparison of average defect size between two groups

| Group A | Group B | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of subjects | 10 | 10 | |

| Average defect size (cm2) | 138 | 143 | >0·05 |

Surgical technique

Each patient underwent a one‐stage operation. Under general anaesthesia, the burned scar was excised, and contracture was released thoroughly. To avoid tendon and other deep tissue exposure, careful resection is necessary, especially in deeply burned cases. We should preserve vital structures to guarantee the following skin graft position and coverage. After soft tissue released satisfactorily, it was required that each affected joint should be mobilised and resumed at a nearly normal range‐of‐motion. Kirschner wire may be necessitated according to the degree of joint motion after full mobilisation. Then, the defect was covered with a 0·5–1 mm thickness sheet of acellular dermis matrix with absorbable sutures. The dermis matrix was generally placed in saline water and washed thrice to remove the storing fluid. A thin split‐thickness graft was then harvested from the back, thigh or scalp sites with powered dermatome (Zimmer, Illinois State, America). The autograft was positioned on the surface of the alloderm to finish the final coverage. A packaging suture was at last executed to safeguard the ample pressure on the composite skin co‐graft. Each package was kept in an appropriate splint for 14 days. An intravenous antibiotic was given to patients for about 7 days. After 14 days, the package was removed to observe if the graft survived or not. Then, functional exercises and anti‐scar procedures were initiated. One patient was operated by bilateral acellular dermis matrix transferring.

Regarding patients with a large nevus, the co‐graft was transplanted to the defect after the pigmented site was removed. The package was also implemented to produce continuous pressure for 14 days accompanied by an intravenous antibiotic dosage for 7 days.

The Vancouver Scar Score Scale was used to evaluate the outcome of the donor site and recipient site.

Results

The mean age of the patients was 25·4 (ranging from 2 to 44, 7 male patients and 11 female patients). Patients were followed‐up for a mean of 12 months. Seven patients underwent Kirschner wire placement. The function of the motion of all scarring hands was improved to a great extent as shown in Table 1. Three patients underwent a bilateral neodermis operation in each patient's bilateral upper extremities (Figure 4), while another three patients were operated on with unilateral composite grafts transplantation in the one affected upper extremity (Figure 1). A giant nevus in two patients were excised and reconstructed by composite grafts (Figure 5). Except the abovementioned eight patients, ten recruited patients who were chosen for a comparative study were arranged for the operation on the bilateral upper extremities at the same time (Figures 2 and 3). No complication was encountered in the process except one little girl. This 3‐year‐old patient with a congenital large nevus had a complication of finger tip necrosis, which was repaired with an abdomen flap. Unfortunately, the finger tip was not ultimately preserved. Another non‐recruited adult patient was dissatisfied with his donor site. The hypertrophic scar was still displayed on the back after 2 years follow‐up while thin‐grafted skin was meshed. In the recipient site, about half of the area became a hypertrophic scar, and the other half of the area was excellent (Figures 4 and 5).

Figure 4.

(A) Bilateral hands scar contracture and ulceration were presented. Co‐graft was used to repair bilateral hands. (B) Function and cosmetics have been improved 10 months postoperatively.

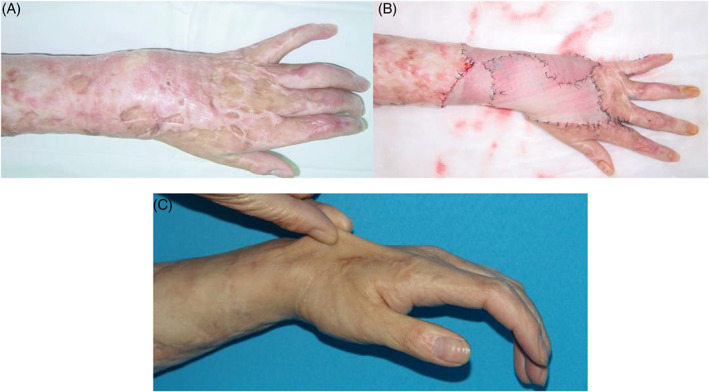

Figure 1.

(A) Left hand and forearm were covered by scar contracture, causing limited motion and cosmetics. (B) Thin split‐thickness skin graft and acellular dermis matrix were combined to repair the large defect after resection and releasing. (C) Excellent aesthetics and function was achieved after 12 months follow‐up. The elaticisty was displayed when the new skin was clenched.

Figure 5.

Left hand was affected with a large nevus (the first row). Co‐graft was used to repair the defect after excision. However, tips of the III, IV and V finger were deformed, while nearly all the nevus was removed after 36 months with no recurrence. The scarring on the back was flattened (the second row).

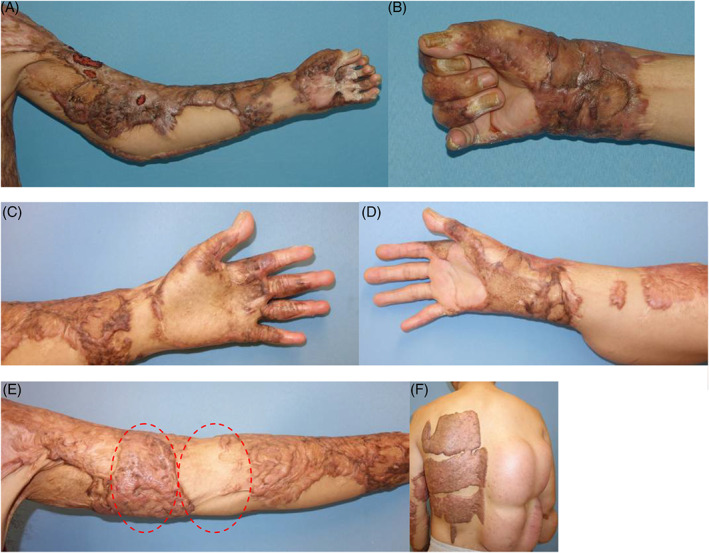

Figure 2.

Right elbow, hand and left burned hand scar contracture can be seen (the first row). A thick skin graft was transplanted to the left hand when a co‐graft was used to repair the right hand and left elbow. Function and cosmetics have improved 24 months postoperatively (the second row). However, the severe hypertrophic scar was developed at the back of the donor site (the rightmost picture of the third row). In the recipient site, the left red marked area was hypertrophic scar, and the right marked area was composite grafts (the leftmost picture of the third row). The expanders were transplanted to reconstruct the hypertrophic scar on the back.

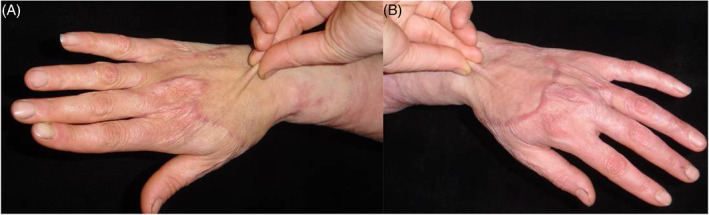

Figure 3.

(A) Bilateral hands scar contracture due to burn injury. Thick split‐skinness skin graft was transplanted to right hand when a co‐graft was used to repair left hand. Function and cosmetics have been improved 12 months postoperatively. When renewed skin was pinched, elasticity was excellent (B).

Recipient and donor site evaluation

The Vancouver Scar Scale was used to appraise the recipient and donor site's functional and aesthetic characteristics (e.g., pliability, contour, color and texture) after a mean of 12 months follow‐up as shown in Tables 3 and 4. In the recipient evaluation, no statistical difference was found in the pigmentation score between the two groups, while statistical difference was achieved in other aspects (vascularity, pliability, height). In the donor site evaluation, statistical difference was established between the two groups in all facets (pigmentation, pliability, vascularity, height).

Table 3.

Comparison of the Vancouver Scar Scale Scores on the recipient site between group A and group B

| Group A | Group B | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pigmentation | 1·6 | 1·8 | >0·05 |

| Vascularity | 1·8 | 2·6 | <0·01 |

| Pliability | 1·8 | 3·0 | <0·01 |

| Height | 0·2 | 0·7 | <0·05 |

| Total | 5·4 | 8·1 | <0·01 |

Table 4.

Comparison of the Vancouver Scar Scale Scores on the donor site between group A and group B

| Group A | Group B | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pigmentation | 1·4 | 2·8 | <0·05 |

| Vascularity | 0·9 | 2·4 | <0·05 |

| Pliability | 0·8 | 2·7 | <0·05 |

| Height | 0·2 | 2·0 | <0·05 |

| Total | 3·3 | 9·9 | <0·01 |

Discussion

Upper extremity motion is the inherent functionality. Cosmetic requirement is also critical because the upper extremities must touch many objects and are seen by other people. Timely releasing scar contracture can make all motion preservation possible. A large nevus is so disfiguring that patients can be sneered at when they try to integrate themselves into society. A split‐thickness skin graft is the fundamental option to reconstruct the secondary defect. However, the skin graft contracture recurrence can be a major challenge of this method. It has been shown that the thickness of the skin graft is inversely associated with subsequent contracture. On the basis of the premise, the optimal choice is a thick‐skin graft. Then, the dissatisfying outcome is donor site morbidity and prolonged healing. When the young patients, especially paediatric cases, are annoyed with the recipient's function and contour, their guardians do not expect another proliferative scarring in the donor sites caused by thick auto‐derma.

Neodermis, as a revolutionary finding meshed from donated skin, has been used for more than 20 years in many types of reconstructive surgery 1, 2, 3, 4. In 1995, Wainwright first reported using acellular dermal matrix on two similar burn patients with full‐thickness burn injuries 5. The early clinical and histological outcomes of acellular dermal matrix grafted simultaneously with overlying meshed split‐thickness skin graft were displayed. He also evaluated the immunogenic response of the host to the grafted matrix. Lattari et al. 6, Gore 7 and Morad Askari et al. 8 reported that acellular dermal matrix with overlying thin meshed autograft was used on the hand after full‐thickness burns. Functional measurements, task performance and cosmetic results were reported as being excellent by patient and family members. Chou et al. 9 reported the use of neodermis in upper extremity contracture release in 13 patients and advance in range of motion and improved skin quality, with no need for reoperation after 2 years. In 2013, Chen et al. 10 reported a prospective randomised study of a total of 30 full‐thickness burn patients. These patients were treated with composite grafts or autologous split‐thickness skin grafts alone. This study reported that no conspicuous rejection was observed, and moreover, treatment with co‐graft showed better skin elasticity and recovery of joint function compared with autologous split‐thickness skin grafts alone. YI et al. 11 reported a prospective randomised comparison of scar appearances between the co‐graft of acellular dermal matrix with autologous split‐thickness skin and autologous split‐thickness skin graft alone for full‐thickness skin defects of the extremities. No statistically significant difference was found regarding complications, including graft necrosis, graft detachment or seroma formation. For cases with traumatic full‐thickness skin defects on the extremities, a statistically significant better result was achieved with co‐graft of acellular dermal matrix with autologous split‐thickness skin graft than with autologous split‐thickness skin graft alone in terms of the Vancouver Scar Scale score. In all the patients in this study, they did not talk about the donor site's result.

Advantages can be acknowledged as decreased donor site morbidity and satisfaction with elasticity and feel of skin compared with conventional meshed split‐thickness skin grafts. In the procedure, the revascularised net form of artificial substitutes become alive, and the capillary loops grow into channels within the graft through the gap of the dermal matrix. Histological studies have shown that human acellular dermis can cause a low inflammatory response and full immunogenic rejection. As a skin substitute, it can play an important role in replacing partial skin thickness when all cells are removed and cleaned. Then, a thick‐skin graft is not necessitated in all those large secondary wounds. The foreign literature delivered has shown that two‐staged procedures are necessary. The alloderma and continuous negative pressure are positioned onto the wound at the first stage, while the auto‐skin graft is harvested to cover the fully vascularised wound at the second stage. Nevertheless, we complete the whole procedure at one stage, avoiding one more operation. From our observations, the net allomderma must be straightened thoroughly to expose all the gaps fully because the autograft development must be benefited from the serum at the base of the wound during the initial 48 hours. The serum must flow freely through all the gaps of the dermal matrix. In order to make autoderma absorb the serum exudation at the initial critical situation, stable pressure should be ensured to make the autograft touch the base of the wound. The negative pressure appliance is not our primary preferred choice for its possible unstable constant pressure. If the operation site cannot be immobilised stably, the following three guaranteed steps are executed, including the inner layer of packaged pressure, media layer of negative pressure appliance and outmost layer of corset‐strengthening pressure.

Statistical difference has been identified in the pigmentation part, while no statistical difference has been found in other aspects (vascularity, pliability, height). From the above statistical results, two methods can bring out nearly the same function and aesthetic outcome in the recipient site. It is proven that the neodermis has played an important role as a part of the skin graft. It can integrate itself into the skin graft. When the donor site is concerned, the degree of scarring is different in the above two methods. The scarring in harvesting thin graft skin of the co‐graft is much less distinct than thick graft skin alone at a later period. So, when we conduct the composite procedure, the thin autologous skin graft should be guaranteed. An experienced surgeon should carry out the procedure. In the little girl suffering from a large nevus in the upper extremity, a nearly complete excision is shown in the picture. However, finger tip necrosis occurred. We regret that the little girl's finger tip could not ultimately be saved because of the preoperative irrational appraisal of affected sites. Her future life may be affected to some extent. We will continue to follow up. The adult patient was dissatisfied with the donor site and almost a half of recipient sites' hypertrophic appearance, which is possibly attributed to inherent diathesis.

Although satisfied results have been achieved, some limitations of the study should be noted. First, the number of the recruited cases is small, and they are adult cases. Fortunately, we are executing this study in paediatric patients. A detailed collection of data will be presented. Second, the region is confined to upper extremity. More regions must be included in the systematic study. For example, we have now introduced the method in the back area. Third, Relatively high costs must be offered. The cost of a cm2 is about 300 RMB in China. A great number of patients could not pay for the expense. The application has not been included in the medical insurance.

Besides the above consideration, we place the co‐graft of the thin scalp skin graft and Integra onto the donor site, while the thick split‐thickness graft is transferred to the recipient site. We expect good results.

Summary

The outcome of the recipient site and donor site can be more satisfactory in a composite graft procedure than the thick‐grafted skin procedure alone.

References

- 1. Livesey SA, Herndon DN, Hollyoak MA, Atkinson YH, Nag A. Transplanted acellular allograft dermal matrix: potential as a template for the reconstruction of viable dermis. Transplantation 1995;60:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Frame JD, Still J, Lakhel‐LeCoadou A, Carstens MH, Lorenz C, Orlet H, Spence R, Berger AC, Dantzer E, Burd A. Use of dermal regeneration template in contracture release procedures: a multicenter evaluation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113:1330–1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tufaro AP, Buck DW II, Fischer AC. The use of artificial dermis in the reconstruction of oncologic surgical defects. Plast Reconstr Surg 2007;120:638–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Salzberg CA. Nonexpansive immediate breast reconstruction using human acellular tissue matrix graft (AlloDerm). Ann Plast Surg 2006;57:1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wainwright DJ. Use of an acellular allograft dermal matrix (AlloDerm) in the management of full‐thickness burns. Burns 1995;21:243–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lattari V, Jones LM, Varcelotti JR, Latenser BA, Sherman HF, Barrette RR. The use of a permanent dermal allograft in full‐thickness burns of the hand and foot: a report of three cases. J Burn Care Rehabil 1997;18:147–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gore DC. Utility of acellular allograft dermis in the care of elderly burn patients. J Surg Res 2005;125:37–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Askari M, Cohen MJ, Grossman PH, Kulber DA. The use of acellular dermal matrix in release of burn contracture scars in the hand. Plast Reconstr Surg 2011;127:1593–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chou TD1, Chen SL, Lee TW, Chen SG, Cheng TY, Lee CH, Chen TM, Wang HJ. Reconstruction of burn scar of the upper extremities with artificial skin. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108:378–384: discussion 385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chen B, Fu JF, Cao WD. Use of heterogeneous acellular dermal matrix and autologous overthin split‐thickness skin for repair of deep burn at articular sites. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi 2001;15:343–6[in Chinese]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yi JW, Kim JK. Prospective randomized comparison of scar appearances between cograft of acellular dermal matrix with autologous split‐thickness skin and autologous split‐thickness skin graft alone for full‐thickness skin defects of the extremities. Plast Reconstr Surg 2015;135:609e–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]