ABSTRACT

Negative pressure wound therapy with instillation and dwell time (NPWTi‐d) is an adjunctive therapy that can be used in the management of complex wounds with infection. NPWTi‐d incorporates the intermittent instillation of a topical solution to the wound in a programmed manner. Unlike standard negative pressure wound therapy, NPWTi‐d delivers topical wound solutions directly to the wound, allows the solution to dwell over the wound bed, and removes the solution during the negative pressure phase. The authors review the evidence for using NPWTi‐d and the role it may potentially play in helping to reduce hospital stay, number of debridement operations and cost.

Keywords: Debridement, Instillation, Limb salvage, Negative pressure wound therapy, Review, Wound healing

Introduction

More patients are being hospitalised with infected wounds than ever before. In the USA, 152 infected wounds per 100 000 hospitalisations are because of diabetic foot ulcers and are associated with increasing inpatient treatment costs, amputations and mortality 1. The need for improved wound management is obvious. Negative pressure wound therapy with instillation and dwell time (NPWTi‐d) presents a potentially important adjunctive approach in the management of complex wounds with infection. The application of NPWTi‐d includes forming an occlusive seal over the wound and alternating the application of negative pressure with the instillation of a topical solution with a dwell time on the wound surface. Negative pressure is thought to aid in wound healing by a number of mechanisms including macrostrain, microstrain, fluid removal and optimising the wound environment 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7. Macrostrain involves drawing the wound edges together to reduce wound size, promoting perfusion and reducing oedema. Microstrain refers to the microdeformation that is created at the foam and wound interface that leads to cell stretch, which may stimulate cellular differentiation and activity 2. Finally, NPWT optimises the wound environment through the removal of fluid and infectious materials. NPWTi‐d combines negative pressure with the intermittent instillation of a topical wound solution of a user‐defined volume and dwell time. During the dwell time, the solution (e.g. topical wound cleansers, antiseptics or saline) remains in contact with the surface of the wound. This is followed by the removal of the solution by NPWT. Contraindications of both NPWTi‐d and NPWT include malignancy in the wound, untreated osteomyelitis, non‐enteric and unexplored fistulas, necrotic tissue with eschar present or sensitivity to silver. Also, dressings should not be placed over exposed blood vessels, anastomotic sites, viscera or nerves. Instillation therapy is contraindicated for the abdominal and thoracic cavities.

Numerous studies have investigated the use of NPWT for complicated wounds in diabetic patients either following amputations, significant surgical intervention or chronic stable ulcers 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14. The consensus is that NPWT is safe, effective and may reduce operative interventions for complicated wounds, including in the challenging population of diabetic patients. Of importance, two of those studies noted infection rates between NPWT and standard wound care 8 or NPWT and NPWTi‐d 14. In the study comparing NPWT with standard moist dressing for patients with wounds secondary to partial foot amputation (up to the metatarsal level), the most commonly reported adverse event was wound infection 8. Seventeen percent of the NPWT cohort as compared to 6% of the standard dressing cohort experienced this complication. Goss et al. reported 13 patients and 16 chronic lower leg wounds treated with either NPWTi‐d (instillation of quarter strength Dakin's solution with a 10‐minute dwell time, followed by 1 hour of NPWT) or standard NPWT 14. The mean absolute reduction in bacteria was 10·6 × 106 bacteria per gram of tissue for the NPWTi‐d group, while there was a mean absolute increase in bacteria of 28·7 × 106 bacteria per gram of tissue for the NPWT group. Overall, the authors reported that there was a statistically significant reduction in the absolute bioburden in those wounds treated with NPWTi‐d (P = 0·016) 14.

There is little evidence for the use of adjunctive NPWT in successfully managing infected wounds. Alternatively, studies in both clinical and animal models have reported that adjunctive NPWTi‐d using a variety of topical solutions may help manage wound bioburden 15, 16 and wounds with infection 17, 18, 19, 20, 21.

NPWTi‐d for complex wounds with infection

While standard NPWT is an established adjunctive therapeutic option for wound bed preparation or non‐operative management for secondary healing, there is limited evidence for its utility in wounds with active or senescent infection. Wounds plagued with acute infection and biofilm are challenging problems that require an intensive multimodal approach, including systemic antibiotics, surgical intervention (i.e. debridement) and local wound care. Adjunctive use of NPWTi‐d may help manage bacterial bioburden through the removal of wound exudate that may contain infectious materials and potential detrimental inflammatory factors (Figure 1). The authors provide a review of the evidence for use of NPWTi‐d in complex wounds.

Figure 1.

Adjunctive use of NPWTi‐d in diabetic patients. Preoperative photograph of a dehisced infected transmetatarsal amputation in a diabetic patient with peripheral vascular disease on dialysis. Note the necrosis along the distal margin of the wound and liquefaction of fat (A). Angiogram depicting the degree of peripheral vascular disease with a patent posterior tibial artery only (B). Intraoperative photograph with NPWTi‐d applied to the wound area (30 ml of normal saline, 20 minutes of dwell time, 2 hours of NPWT at −125 mmHg) (C). Three days postoperatively after initial debridement and application of NPWTi‐d. Note the improvement in quality (D). Fully healed complex wound 1‐month post‐surgery (E).

The earliest reports of NPWTi‐d use are from a pilot study and a retrospective cohort study. The pilot study from Gabriel et al. assessed the use of NPWTi‐d with silver nitrate in 15 patients with complex infected wounds compared to a retrospective historical control population (n = 15) that was treated with moist gauze wound care 17. The NPWTi‐d group required significantly fewer treatment days (9·9 ± 4·3 days versus 36·5 ± 13·1 days, P < 0·001), achieved wound closure sooner (13·2 ± 6·8 versus 29·6 ± 6·5 days, P < 0·001) and had shorter inpatient length of stay (14·7 ± 9·2 versus 39·2 ± 12·1 days, P < 0·001) 17. The Timmers et al. retrospective cohort study utilised NPWTi‐d in patients (n = 30) with post‐traumatic osteomyelitis 18. The matched control group (n = 94) received standard wound care, which included the use of antibiotic beads. Instillation solution utilised was a 0·04% polyhexanide solution for 10–15 minutes dwell time, with negative pressure of 300–600 mmHg applied through a prototype negative pressure therapy system. The infection recurrence rate was 10% for the NPWTi‐d group compared with 58·5% in the control group (P < 0·0001) 18. A case series of 131 patients with a variety of complex wounds reported a 98% wound closure rate with the adjunctive use of NPWTi‐d (instillation of normal saline (NS) with a 10‐minute dwell time, followed by negative pressure at −125 mmHg between 4 and 12 hours) 22.

Studies conducted in porcine models may support the adjunctive use of NPWTi‐d in infected wounds 15, 16. The two porcine wound models evaluated NPWT and NPWTi‐d on their ability to help manage bioburden, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Davis et al. found that NPWTi‐d (solution of NS or 0·1% polyhexanide +0·1% betaine (PHMB)) had a positive effect on reducing bioburden compared to the control and NPWT alone 15. Philips et al. reported, in a porcine skin explants model of mature biofilm, that the delivery of the majority of the antimicrobial agents tested through the NPWTi‐d system led to a significant logarithmic decrease in the colony‐forming units of bacteria as compared with NPWT alone 16. Interestingly, unlike the Davis et al. study, NS had no effect on the bioburden. Although FDA has not approved any topical wound solutions for the treatment of infection, and NPWTi‐d is not indicated for this purpose, the reported effect that NPWTi‐d has on bioburden could be because of the repetitive loosening of bioburden from the presence of surface‐active agents in certain topical wound solutions and/or the repetitive cycles of wound cleaning and removal of exudate.

A comparison between NPWT (n = 74) and NPWTi‐d (n = 74) was completed in a retrospective, historical‐cohort controlled study conducted, with 142 patients requiring hospitalisation for acutely infected wounds 19. The patient population was comprised of complex patients with multiple comorbidities, including a significant portion of patients with diabetes mellitus, peripheral vascular disease and end‐stage renal disease. All patients received systemic antibiotics and surgical debridement. Data from patients treated with two different dwell times and negative pressure durations (n = 34, 6 minutes of dwell time and 3·5 hours of negative pressure and n = 34, 20 minutes of dwell time and 2 hours of negative pressure) for NPWTi‐d utilising Prontosan® Wound Irrigation Solution (B. Braun Medical Inc., Bethlehem, PA) were compared with data from a historical cohort of patients treated with standard NPWT (n = 74). The results revealed a significant decrease in the number of debridement operations (6‐ and 20‐minute dwell groups, P = 0·043 and P = 0·003, respectively), length of hospital stay (20‐minute dwell group, P = 0·034) and time to final surgical procedure (6‐ and 20‐minute dwell groups, P = 0·043 and P = 0·0019, respectively). An increase in the proportion of closed/covered wounds prior to discharge was significantly different between the NPWTi‐d groups versus the standard NPWT group (94% versus 64%, respectively; P = 0·0004).

NPWTi‐d for complex hosts

Patients with multiple comorbidities present as complex hosts who have intrinsic disadvantages to wound healing. The authors define a complex host as those patients who have an American Society of Anesthesiology Classification of ≥ 2, multiple comorbidities and severe traumatic wounds. Patients with combinations of diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, pulmonary disease, renal disease and a history of smoking were predominant in the studies reviewed evaluating NPWTi‐d 14, 18, 19, 20, 22. These patients are characterised by impaired regenerative potential, poor circulation and nutritional deficits. Often, these patients are unable to mount a strong immune response and have limited physiological reserves. Therefore, when considering the use of NPWTi‐d as an adjunctive therapy, the compromised host may be the most appropriate individual to receive this type of therapy (Figure 2).

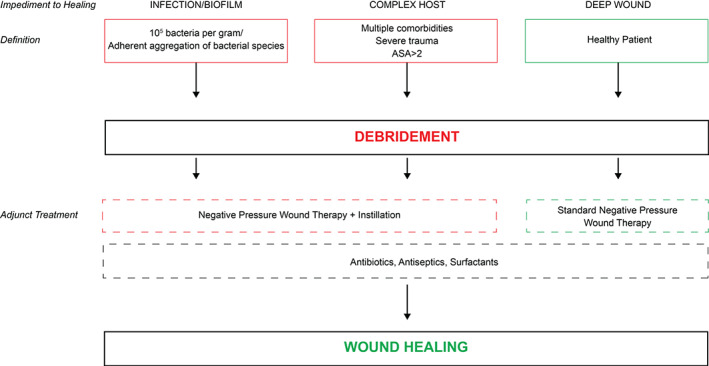

Figure 2.

Management schema for wounds using NPWT with or without instillation as adjunctive therapy. ASA, American Society of Anesthesiology Classification.

NPWTi‐d solution choice

The choice for the ideal instillation solution remains unanswered. In 2013, consensus guidelines regarding NPWTi‐d were published by a multidisciplinary panel including general, plastics, vascular, podiatric and orthopaedic surgeons 23. Consensus statements regarding choice of appropriate instillation solution included the use of PHMB and Dakin's solution. Interestingly, normal saline received only a 55% approval rating and did not reach consensus. In vivo animal studies evaluating NPWTi‐d with varied solutions report conflicting findings. Philips et al. found that from a base of 7‐log colony‐forming units, NPWTi‐d with normal saline reduced counts by 1‐log as compared to instillation of 1% povidone iodine (2‐log), 0·05% chlorhexidine gluconate (3‐log), 0·1% PHMB (4‐log) and 10% povidone iodine (5‐log) (P < 0·001), showing a clear preference for the use of antiseptic agents 16. Davis et al. reported similar outcomes between normal saline and PHMB 15. Both studies have limitations that are inherent to all animal models in that human anatomy and physiology are different.

There is speculation that the effectiveness of PHMB is based on the betaine component of this solution. Betaine is a surface‐active agent that may promote detachment of debris. Interestingly, a recent article on the management of open fractures requiring wound irrigation found higher re‐operation rates in the group treated with castile soap (a surfactant) compared with normal saline 24. This study calls into question the value of surfactant‐containing solutions compared to normal saline.

Recently a prospective, randomised, comparative efficacy clinical study of NPWTi‐d was published comparing NS (n = 49) to PHMB (n = 51) for the adjunctive treatment of infected wounds 20. Dwell time for both groups was 20 minutes, followed by 2 hours of negative pressure. One hundred patients were randomised to the intention‐to‐treat analysis (ITT) and 83 patients randomised to the per protocol (PP) analysis. All patients received systemic antibiotics and surgical debridement. Patients in each cohort were demographically equivalent with the exception of gender; more males were included in the PHMB cohort as compared with the NS cohort (P = 0·004). The cohorts were statistically matched for smoking history, wound location and wound aetiology. The results revealed that there was no statistically significant difference between the cohorts for the number of operating room visits, length of stay, proportion of wounds closed/covered and proportion of wounds that remained closed at the 30‐day follow‐up. There was a statistically significant difference between the NS and the PHMB cohorts for the time to final surgical procedure (ITT: 5·73 ± 3·75, 7·73 ± 5·49, respectively, P = 0·038) (per protocol: 5·57 ± 3·61, 7·46 ± 4·42, respectively, P = 0·035), favouring NS. These results suggest that NS may be as effective as PHMB when using NPWTi‐d for the adjunctive inpatient management of infected wounds 20.

As presented here, there is still debate over which topical wound solution is most appropriate for instillation when using NPWTi‐d. There is higher‐level clinical evidence to support NS use as it has similar outcomes to at least one well‐studied solution (PHMB) 20. The results of one clinical trial should not be considered definitive, and similar studies are needed to evaluate other solutions and substantiate the presented findings. The authors speculate that it may not matter which solution is used with NPWTi‐d. Most likely, there are yet undetermined mechanisms at work, which may include washing away of deleterious inflammatory factors with each cycling of this device. Clinicians should evaluate the unique properties of the topical wound solution, including its activity, toxicity/tolerability, availability and cost when selecting an instillation solution.

Wound healing with NPWTi‐d

In order to prevent re‐infection, complete wound healing is required. Granulation tissue formation reflects the second phase of wound healing and is essential in establishing robust soft tissue coverage. Furthermore, granulation tissue can be used as a marker of overall wound health, including decreased bioburden. The ability of NPWTi‐d to stimulate granulation tissue formation was investigated in a non‐infected porcine model study 25. NPWTi‐d with saline instillation was compared to standard continuous NPWT, intermittent NPWT and controlled variable NPWT, all used for a 7‐day duration. Average granulation thickness was not statistically different between the NPWT treatments (3·29 ± 0·33, 3·03 ± 0·47, 3·40 ± 0·34 mm, respectively). NPWTi‐d‐treated wounds did have statistically significant thicker granulation tissue (4·75 ± 0·54 mm) than NPWT groups (P < 0·05). Furthermore, three‐dimensional image analysis revealed greater wound area reduction in NPWTi‐d than all NPWT groups (P < 0·05). All of these results have not been confirmed in human studies. These preclinical data support the use of NPWTi‐d for promoting granulation tissue formation.

A surgical approach involving excisional debridements, followed by staged soft tissue coverage, has shown promising results but has not been previously validated. In a yet unpublished study, the authors conducted a prospective longitudinal effectiveness study to examine the surgical management of infected wounds requiring hospitalisation. All patients had systemic antibiotics and at least two excisional debridements along with NPWTi‐d between surgeries. Number of operative visits, length of stay, time to final surgical procedure and proportion of closed, infected or dehisced wounds at 30, 60, 90, 180 and 360 days were measured. Preliminary results revealed a 75% healing rate achieved at 360 days after initial presentation (E.L. Anghel, unpublished data, May 2016). These results are encouraging considering the complexity of the patients requiring hospital admission with operative management. Following adjunctive NPWTi‐d, closure types included primary closure, autologous skin graft, bioengineered alternative tissues and healing by secondary intention. Simple techniques can work in complex comorbid patients as long as appropriate wound bed preparation is achieved. The adjunctive use of NPWTi‐d with excisional surgical debridement and appropriate antibiotic therapy presents a promising option for the management of infected and complex wounds.

Summary

There have been significant advances in the understanding of NPWTi‐d with an increase in practical experience as well as a growing body of clinical evidence. Questions remain regarding the most appropriate device settings, the choice of instillation solutions and mechanism of action. There is evidence that suggests that NPWTi‐d is a viable option for the adjunctive management of complex wounds with infection, particularly in the compromised host, along with appropriate debridement and antibiotic therapy. NPWTi‐d can be used with a range of topical wound solutions, and early in vitro work comparing the outcomes of an antiseptic solution with NS showed no difference 26. A robust, multicentre, prospective, randomised controlled trial comparing NPWT to NPWTi‐d in adjunctively managing complex wounds with infection is warranted. Overall, this therapeutic approach holds potential and should be considered in select patients.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Attinger presented as a faculty member at an ACELITY symposium parallel to the 2016 World Union of Wound Healing Societies (WUWHS) conference. This article is part of an ACELITY‐funded supplement based on the 2016 WUWHS Acelity symposium presentations. ACELITY provided editorial assistance.

Ersilia Anghel has no financial disclosures, commercial associations or any other conditions posing a conflict of interest to report. Dr. Kim has received consulting and research funding from KCI, an ACELITY Company, and Integra LifeSciences Corp. Dr. Attinger is a consultant for KCI, an ACELITY Company, Smith & Nephew Inc. and Integra Life Sciences Corp.

References

- 1. Hicks CW, Selvarajah S, Mathioudakis N, Perler BA, Freischlag JA, Black JH III, Abularrage CJ. Trends and determinants of costs associated with the inpatient care of diabetic foot ulcers. J Vasc Surg 2014;60:1274–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Huang C, Leavitt T, Bayer LR, Orgill DP. Effect of negative pressure wound therapy on wound healing. Curr Probl Surg 2014;51:301–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Saxena V, Hwang CW, Huang S, Eichbaum Q, Ingber D, Orgill DP. Vacuum‐assisted closure: microdeformations of wounds and cell proliferation. Plast Reconstr Surg 2004;114:1086–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McNulty AK, Schmidt M, Feeley T, Kieswetter K. Effects of negative pressure wound therapy on fibroblast viability, chemotactic signaling, and proliferation in a provisional wound (fibrin) matrix. Wound Repair Regen 2007;15:838–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McNulty AK, Schmidt M, Feeley T, Villanueva P, Kieswetter K. Effects of negative pressure wound therapy on cellular energetics in fibroblasts grown in a provisional wound (fibrin) matrix. Wound Repair Regen 2009;17:192–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Venturi ML, Attinger CE, Mesbahi AN, Hess CL, Graw KS. Mechanisms and clinical applications of the vacuum‐assisted closure (VAC) device: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol 2005;6:185–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Argenta LC, Morykwas MJ. Vacuum‐assisted closure: a new method for wound control and treatment: clinical experience. Ann Plast Surg 1997;38:563–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Armstrong DG, Lavery LA, Diabetic Foot Study Consortium . Negative pressure wound therapy after partial diabetic foot amputation: a multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2005;366:1704–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tuncel U, Erkorkmaz U, Turan A. Clinical evaluation of gauze‐based negative pressure wound therapy in challenging wounds. Int Wound J 2013;10:152–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Blume PA, Walters J, Payne W, Ayala J, Lantis J. Comparison of negative pressure wound therapy using vacuum‐assisted closure with advanced moist wound therapy in the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care 2008;31:631–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Karatepe O, Eken I, Acet E, Unal O, Mert M, Koc B, Karahan S, Filizcan U, Ugurlucan M, Aksoy M. Vacuum assisted closure improves the quality of life in patients with diabetic foot. Acta Chir Belg 2011;111:298–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sajid MT, Mustafa QU, Shaheen N, Hussain SM, Shukr I, Ahmed M. Comparison of negative pressure wound therapy using vacuum‐assisted closure with advanced moist wound therapy in the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak 2015;25:789–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vaidhya N, Panchal A, Anchalia MM. A new cost‐effective method of NPWT in diabetic foot wound. Indian J Surg 2015;77:525–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Goss SG, Schwartz JA, Facchin F, Avdagic E, Gendics C, Lantis JC II. Negative pressure wound therapy with instillation (NPWTi) better reduces postdebridement bioburden in chronically infected lower extremity wounds than NPWT alone. J Am Coll Clin Wound Spec 2014;4:74–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Davis K, Bills J, Barker J, Kim P, Lavery L. Simultaneous irrigation and negative pressure wound therapy enhances wound healing and reduces wound bioburden in a porcine model. Wound Repair Regen 2013;21:869–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Phillips PL, Yang Q, Schultz GS. The effect of negative pressure wound therapy with periodic instillation using antimicrobial solutions on Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm on porcine skin explants. Int Wound J 2013;10:48–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gabriel A, Shores J, Heinrich C, Baqai W, Kalina S, Sogioka N, Gupta S. Negative pressure wound therapy with instillation: a pilot study describing a new method for treating infected wounds. Int Wound J 2008;5:399–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Timmers MS, Graafland N, Bernards AT, Nelissen RG, van Dissel JT, Jukema GN. Negative pressure wound treatment with polyvinyl alcohol foam and polyhexanide antiseptic solution instillation in posttraumatic osteomyelitis. Wound Repair Regen 2009;17:278–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kim PJ, Attinger CE, Steinberg JS, Evans KK, Powers KA, Hung RW, Smith JR, Rocha ZM, Lavery L. The impact of negative‐pressure wound therapy with instillation compared with standard negative‐pressure wound therapy: a retrospective, historical, cohort, controlled study. Plast Reconstr Surg 2014;133:709–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kim PJ, Attinger CE, Oliver N, Garwood C, Evans KK, Steinberg JS, Lavery LA. Comparison of outcomes for normal saline and an antiseptic solution for negative‐pressure wound therapy with instillation. Plast Reconstr Surg 2015;136:657e–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gabriel A, Kahn K, Karmy‐Jones R. Use of negative pressure wound therapy with automated, volumetric instillation for the treatment of extremity and trunk wounds: clinical outcomes and potential cost‐effectiveness. Eplasty 2014;14:e41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Brinkert D, Ali M, Naud M, Maire N, Trial C, Teot L. Negative pressure wound therapy with saline instillation: 131 patient case series. Int Wound J 2013;10:56–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kim PJ, Attinger CE, Steinberg JS, Evans KK, Lehner B, Willy C, Lavery L, Wolvos T, Orgill D, Ennis W, Lantis J, Gabriel A, Schultz G. Negative‐pressure wound therapy with instillation: International Consensus Guidelines. Plast Reconstr Surg 2013;132:1569–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bhandari M, Jeray KJ, Petrisor BA, Devereaux PJ, Heels‐Ansdell D, Schemitsch EH, Anglen J, Della Rocca GJ, Jones C, Kreder H, Liew S, McKay P, Papp S, Sancheti P, Sprague S, Stone TB, Sun X, Tanner SL, Tornetta P III, Tufescu T, Walter S, Guyatt GH. A trial of wound irrigation in the initial management of open fracture wounds. N Engl J Med 2015;373:2629–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lessing MC, James RB, Ingram SC. Comparison of the effects of different negative pressure wound therapy modes‐continuous, noncontinuous, and with instillation‐on porcine excisional wounds. Eplasty 2013;13:e51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kim PJ, Attinger CE, Crist BD, Gabriel A, Galiano RD, Gupta S, Lantis JC II, Lavery L, Lipsky BA, Teot L. Negative pressure wound therapy with instillation: review of evidence and recommendations. Podiatry Today 2015;27:s2–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]