Abstract

The present study assesses the efficacy and safety of topical sevoflurane in chronic venous ulcers and its impact on analgesia and healing.

This retrospective study included 30 patients older than 65 years with painful refractory chronic venous ulcers. Patients were treated with topical sevoflurane prior to the usual ulcer cleaning every 2 days for a period of 1 month. Treatment was initiated with a saline solution, followed by direct irrigation of 1 ml of liquid sevoflurane over the wound size, which was measured as cm2.

Sevoflurane had a fast, intense and long‐lasting analgesic effect. Latency time ranged from 2 to 7 minutes (3·9 ± 1·5 minutes), and duration varied from 8 to 18 hours (12 ± 2·9). The mean ulcer size was 8·4 ± 9·7 cm2. There was a progressive decrease in size in all patients, with a mean size of 4·2 ± 5·4 cm2 at the end of the study. There were no adverse systemic effects. Local adverse effects were mild and transient, including pruritus, erythema and heat.

Topical sevoflurane is a new, efficient and safe therapeutic alternative in painful chronic venous ulcers, refractory to usual analgesic treatment. It can improve the ulcer‐healing process that shortens the cicatrisation period.

Keywords: Anaesthesia, Chronic ulcer, Cicatrisation, Pain, Sevoflurane

Introduction

Chronic venous ulcers (CVU) are a very common wound type with a high epidemiological, physical, economical and social impact 1, 2. A long evolution, the size, the infection, the use of topical and systemic long term antibiotics, a previous history of ulcer, a lack of compliance with treatment and a bad adherence to compressive therapy worsen prognosis for healing 3, 4, 5, 6. Time of evolution and size are the most important factors 5. Positive psychological factors, such as hope, acceptance and optimism, allow an increased treatment adherence and an improved healing rate 7.

Pain in CVU commonly increases with usual cleaning, surgical debridement and dressing changes 8. Pain worsens treatment adherence, quality of life and healing of ulcers 9, 10, 11. Patients require a multidisciplinary therapeutic approach. The patient's pain is usually poorly controlled not receiving any analgesic treatment 12, 13. Debridement and dressing application reach a healing rate of 65–85%. Nevertheless, around 25% of ulcers become chronic, with morbidity and health costs increased 1, 2.

Sevoflurane is an inhaled halogenated anaesthetic agent with an adequate safety profile, used for induction and maintenance of general anaesthesia in hospital and ambulatory surgery 14. Its efficacy has been reported in a few case reports as a topical anaesthetic in leg ulcers 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23. Our purpose is to assess the efficacy and safety of topical sevoflurane in CVU and its impact on analgesia and healing.

Materials and methods

We present a retrospective study of a series of 30 cases. Patients over 65 years of age with painful CVU expressed by a Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) equal to or greater than four points were included. Written consent was obtained from patients for the off‐label use of topical sevoflurane for painful leg ulcers. The drug and the study protocol were approved both by a Pharmacy Committee and our Hospital Ethics Committee. We excluded hospitalised patients and patients with ulceration of any other cause, generalised arteriosclerosis, cognitive impairment or pain for another cause. The sample is directly conditioned by the number of cases that received this treatment. Each patient is his or her own self‐control, evaluating and analysing all variables that occurred in an initial cleaning without sevoflurane and then successive cleanings with sevoflurane.

Those patients received previous standard cleaning without topical sevoflurane or other drug. In an initial visit, NRS and wound size in cm2 was registered, corresponding to the previous cleanings without sevoflurane. An initial cleaning without sevoflurane was performed. Cleaning visits with sevoflurane every 2 days for a period of 1 month were scheduled. We compared the NRS and wound size results of the previous and initial cleanings without sevoflurane and the subsequent treatments with sevoflurane in the 1st, 2nd, 7th and 12th cleanings.

Treatment consisted of cleaning initially with a saline solution and irrigating with 1 ml of liquid sevoflurane every cm2 of the wound size without exceeding the edges of healthy skin, using sterile gauze to protect the perilesional skin. The dose of sevoflurane varied depending on the size of the wound. After that, the wound was quickly covered with a sterile hydrophilic braided cotton pad, soaked in physiological saline. Later, the usual routine cleaning was performed.

A univariate analysis of all variables was performed. Comparisons consisted of a mean chart for quantitative variables. The average standard error has been used as a reference in each one of the bars in order to make a visual comparison of the mean between each one of the categories. For qualitative variables, comparison was made using bar graphs and applying the chi‐square test to compare relationships between each of the categories.

Results

The study consisted of 30 patients, 20 women (66·7%) and 10 men (33·3%). The age of the patients varied from 66 to 90 years (76 ± 6 years). Women were older (78·3 ± 6 years) than men (71·3 ± 3·2 years). Of the patients, 13 patients (43·3%) demonstrated dyslipidaemia, 25 (83·3%) hypertension and 7 (23·3%) obesity, but none had a metabolic syndrome; 16 patients (53·3%) had the ulcer on the right leg and 14 (46·7%) on the left leg. They had ulcers different locations. The time of evolution was found to range from 4 to 24 months (10 ± 5·3 months).

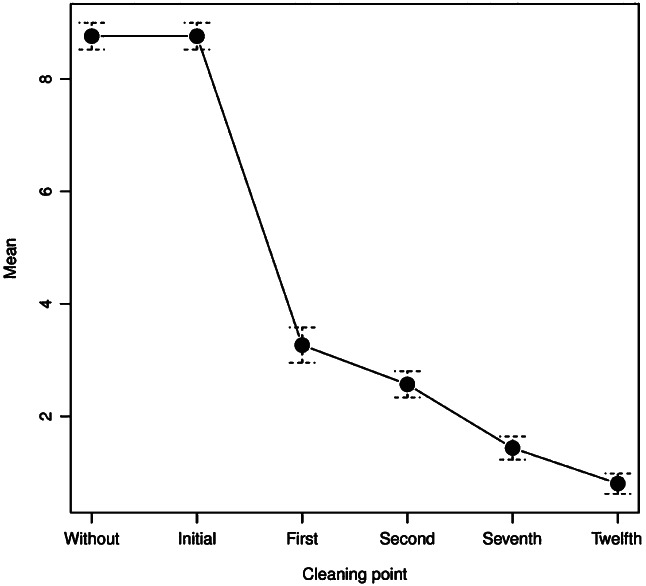

Sevoflurane had an intense analgesic effect. Without sevoflurane, mean NRS was 8·8 ± 1·3 points, and in the 12th cleaning, the mean NRS was 0·8 ± 1 point (Figure 1). Latency time ranged from 2 to 7 minutes (3·9 ± 1·5 minutes). Duration varied from 8 to 18 hours (12 ± 2·9 hours). The analgesic effect duration was always the same for each patient throughout the cleanings.

Figure 1.

Numeric rating scale of cleaning.

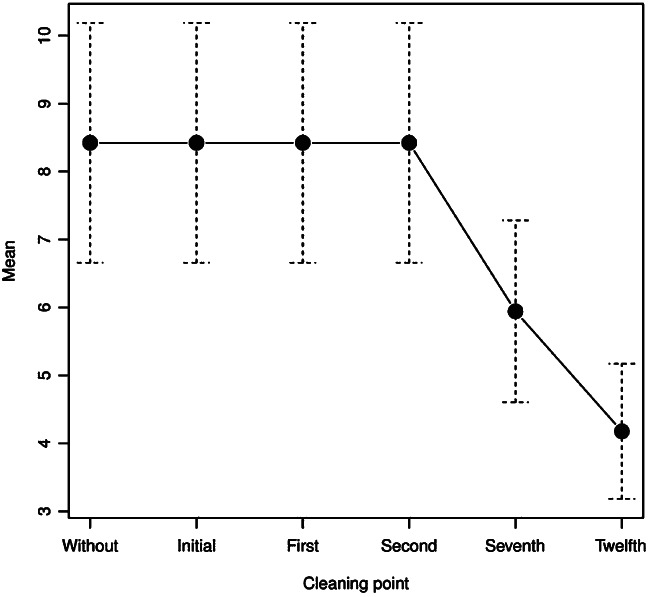

The mean ulcer size was 8·4 ± 9·7 cm2 in the previous, initial and first cleanings (Table 1). From the seventh cleaning with sevoflurane, a progressive decrease in size was achieved in all patients, being statistically significant in the 12th cleaning with a mean of 4·2 ± 5·4 cm2 (P = 0·001) (Figures 2 and 3).

Table 1.

Chronic venous ulcer size in cm2

| Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Standard deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Previous cleaning without sevoflurane | 1 | 40·5 | 8·4 | 9·7 |

| Initial cleaning without sevoflurane | 1 | 40·5 | 8·4 | 9·7 |

| First cleaning with sevoflurane | 1 | 40·5 | 8·4 | 9·7 |

| Second cleaning with sevoflurane | 1 | 40·5 | 8·4 | 9·7 |

| Seventh cleaning with sevoflurane | 0·35 | 32 | 5·9 | 7·3 |

| Twelfth cleaning with sevoflurane | 0·04 | 24·5 | 4·2 | 5·4 |

Figure 2.

Chronic venous ulcer size in cm2.

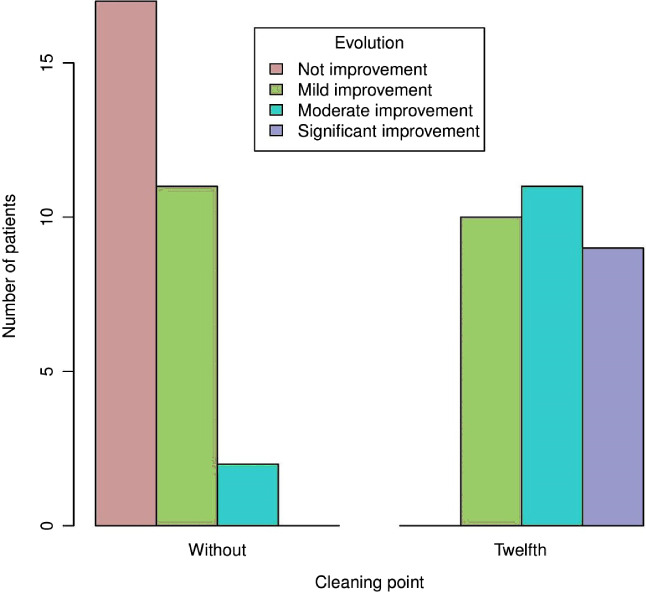

Figure 3.

Subjective evolution of the ulcer of the patient before using topical sevoflurane and after the 12th cleaning with sevoflurane.

The ulcer deepness reduced from the seventh cleaning with sevoflurane (P = 0·001) (Table 2). All ulcers had erythematous edges. The bottom ulcer was dirty in two cases before sevoflurane treatment. However, the bottom ulcer was clean after the first cleaning with sevoflurane in all the patients. A reduction of the exudate and fibrin was also observed after successive cleanings with sevoflurane.

Table 2.

Chronic venous ulcer depth

| Upper dermis | Mid‐dermis | Lower dermis | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Previous cleaning without sevoflurane | 1 (3·3%) | 25 (83·3%) | 4 (13·3%) |

| Initial cleaning without sevoflurane | 1 (3·3%) | 25 (83·3%) | 4 (13·3%) |

| First cleaning with sevoflurane | 1 (3·3%) | 25 (83·3%) | 4 (13·3%) |

| Second cleaning with sevoflurane | 1 (3·3%) | 25 (83·3%) | 4 (13·3%) |

| Seventh cleaning with sevoflurane | 15 (50%) | 15 (50%) | 0 |

| Twelfth cleaning with sevoflurane | 23 (76·7%) | 7 (23·3%) | 0 |

Main local adverse effects were mild and transient, including pruritus, erythema and local heat in five patients (16·7%). None required stopping the drug. No systemic adverse effects were observed.

Discussion

Isolated cases and small patient series with topical sevoflurane for chronic ulcers were reported previously. Topical sevoflurane has an intense, quick and long‐lasting analgesic effect. The latency time varies between 1 and 10 minutes, and the duration ranges between 7 and 24 hours 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23. Until now, we report the study with the highest number of patients with chronic venous ulcers treated with topical sevoflurane.

A central, but not a peripheral, effect of the inhaled sevoflurane has been clinically demonstrated. Topical sevoflurane could have a reversible peripheral analgesic effect, depending on concentration, probably caused by sufficient partial pressure in the peripheral nociceptors that blocks the pain stimulus transmission 24, 25, 26, 27, 28. However, the exact mechanism of action of the analgesic effect is unknown.

Our results show that topical sevoflurane have an epithelising effect, diminishing the time to healing. In previous reports, a progressive diminishing of size and deepness of the ulcer treated with sevoflurane in successive cleanings along some weeks has been reported 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23.

An experiment with rats explores cicatrisation with the exposure of complete skin defects to oxygen and sevoflurane gas type 29. A delayed cicatrisation is observed with a longer exposure time of sevoflurane. A diminished collagen type 1 synthesis, an absence of collagen fibre maturation, a larger acute phase inflammatory cells accumulation and a lower transforming growth factor‐β1 and basic fibroblastic growing factor expression were observed. These authors conclude that sevoflurane exposure can alter the inflammatory phase of the healing process and delay it by decreasing the growing factors and collagen synthesis.

We suggest that healing effects can occur as a result of a vasodilator effect improving microcirculation, increasing the intake of nutrients and oxygen and decreasing inflammatory agents. Sevoflurane may have a vasodilator effect by a direct inhibitor effect on the vascular smooth muscle independent of the endothelium 30.

Local adverse effects are mild and transient, including pruritus and erythema in the wound edges and the burning sensation in the ulcer and the healthy perilesional skin. Until now, these effects have not been described as a sensitisation to topical sevoflurane. The absence of systemic adverse effects is probably a result of a scarce or null, slow and incomplete systemic absorption.

Limitations include the retrospective nature of the study and the relatively small number of patients. Randomised clinical trials and larger prospective studies with longer follow‐up are needed to better assess the analgesic and healing effects of topical sevoflurane.

Conclusion

Topical sevoflurane is an innovative therapeutic alternative for painful refractory CVU. It has an intense, fast and long‐lasting analgesic effect with a very favourable safety profile. It can improve wound healing probably because of a vasodilator and analgesic effect.

References

- 1. Valencia IC, Falabella A, Kirsner RS, Eaglstein WH. Chronic venous insufficiency and venous leg ulceration. J Am Acad Dermatol 2001;44:401–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kelechi TJ, Johnson JJ, Yates S. Chronic venous disease and venous leg ulcers: an evidence‐based update. J Vasc Nurs 2015;33:36–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Abbade LP, Lastoria S, Rollo HA. Venous ulcer: clinical characteristics and risk factors. Int J Dermatol 2011;50:405–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Scotton MF, Miot HA, Abbade LP. Factors that influence healing of chronic venous leg ulcers: a retrospective cohort. An Bras Dermatol 2014;89:414–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Milic DJ, Zivic SS, Bogdanovic DC, Karanovic ND, Golubovic ZV. Risk factors related to the failure of venous leg ulcers to heal with compression treatment. J Vasc Surg 2009;49:1242–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Phillips TJ, Machado F, Trout R, Porter J, Olin J, Falanga V. Prognostic indicators in venous ulcers. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000;43:627–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rozanski A, Blumenthal JA, Kaplan J. Impact of psychological factors on the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease and implications for therapy. Circulation 1999;99:2192–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nemeth KA, Harrison MB, Graham ID, Burke S. Pain in pure and mixed aetiology venous leg ulcers: a three‐phase point prevalence study. J Wound Care 2003;12:336–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Guarnera G, Tinelli G, Abeni D, Di Pietro C, Sampogna F, Tabolli S. Pain and quality of life in patients with vascular leg ulcers: an Italian multicentre study. J Wound Care 2007;16:347–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Duque MI, Yosipovitch G, Chan YH, Smith R, Levy P. Itch, pain, and burning sensation are common symptoms in mild to moderate chronic venous insufficiency with an impact on quality of life. J Am Acad Dermatol 2005;53:504–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Renner R, Gebhardt C, Simon JC, Seikowski K. Changes in quality of life for patients with chronic venous insufficiency, present or healed leg ulcers. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2009;7:953–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Woo KY. Meeting the challenges of wound‐associated pain: anticipatory pain, anxiety, stress, and wound healing. Ostomy Wound Manage 2008;54:10–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Green J, Jester R, McKinley R, Pooler A. Patient perspectives of their leg ulcer journey. J Wound Care 2013;22:58–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Behne M, Wilke HJ, Harder S. Clinical pharmacokinetics of sevoflurane. Clin Pharmacokinet 1999;36:13–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lafuente‐Urrez RF, Gilaberte Y. Sevoflurane: a valid alternative for the treatment of vascular ulcers? Actas Dermosifiliogr 2014;105:202–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gerónimo‐Pardo M, Martínez‐Monsalve A, Martínez‐Serrano M. Analgesic effect of topical sevoflurane on venous ulcer intractable pain. Phlebologie 2011;40:95–7. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Martinez Monsalve A, Gerónimo PM. Sevoflurano como anestésico local en herida isquémica de paciente cardiópata con insuficiencia respiratoria secundaria a morfina. Heridas y cicatrización 2011;6:46–9. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rueda‐Martínez JL, Gerónimo‐Pardo M, Martínez‐Monsalve A, Martínez‐Serrano M. Topical sevoflurane and healing of a post‐operative surgical site superinfected by multi‐drug‐resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa and susceptible Staphylococcus aureus in an immunocompromised patient. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2014;15:843–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gerónimo Pardo M, Martinez Serrano M, Martínez Molsalve A, Rueda Martínez JL. Usos alternativos del sevoflurano. Efecto analgésico tópico. Rev Electron AnestesiaR 2012;4:181. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Imbernón A, Blázquez C, Puebla A, Churruca M, Lobato A, Martínez M, Aguilar A, Gallego MA. Chronic venous ulcer treatment with topical sevoflurane. Int Wound J 2016;13:1060–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dámaso Fernández‐Ginés F, Cortiñas‐Sáenz M, Mateo‐Carrasco H, de Aranda AN, Navarro‐Muñoz E, Rodríguez‐Carmona R, Fernández‐Sánchez C, Sierra‐García F, Morales‐Molina JA. Efficacy and safety of topical sevoflurane in the treatment of chronic skin ulcers. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2017;74:176–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dámaso Fernández‐Ginés F, Cortiñas‐Sáenz M, Navajas‐Gómez de Aranda A, Yoldi Bocanegra R, Sierra‐García F. Reply: to Chronic venous ulcer treatment with topical sevoflurane by Imbernón et al. Int Wound J 2017;14:591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fernández FD, Cortiñas M, Fernández C, Morales JA. Sevoflurano tópico: una nueva opción terapéutica paliativa en las úlceras cutáneas. Med Paliativa 2015;180:5. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chu CC, Wu SZ, Su WL, Shieh JP, Kao CH, Ho ST, Wang JJ. Subcutaneous injection of inhaled anesthetics produces cutaneous analgesia. Can J Anaesth 2008;55:290–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Skouteri I, Staikou C, Sarantopoulos C, Siafaka I, Fassoulaki A. Local application of halothane, isoflurane or sevoflurane increases the response to an electrical stimulus in humans. Acta Anaesthesiol Belg 2007;58:169–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fassoulaki A, Skouteri I, Siafaka I, Sarantopoulos C. Local application of volatile anesthetics attenuates the response to a mechanical stimulus in humans. Can J Anaesth 2005;52:951–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Matute E, Rivera‐Arconada I, López‐García JA. Effects of propofol and sevoflurane on the excitability of rat spinal moto‐neurones and nociceptive reflexes in vitro. Br J Anaesth 2004;93:422–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Antognini JF, Kien ND. Potency (minimum alveolar anesthetic concentration) of isoflurane is independent of peripheral anesthetic effects. Anesth Analg 1995;81:69–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lee HJ, Kwon JY, Shin SW, Baek SH, Choi KU, Jeon YH, Kim WS, Bae JH, Choi HJ, Kim HK, Baik SW. Effects of sevoflurane on collagen production and growth factor expression in rats with an excision wound. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2010;54:885–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Izumi K, Akata T, Takahashi S. The action of sevoflurane on vascular smooth muscle of isolated mesenteric resistance arteries (part 1): role of endothelium. Anesthesiology 2000;92:1426–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]