Abstract

The management of complex abdominal problems with the ‘open abdomen’ (OA) technique has become a routine procedure in surgery. The number of cases treated with an OA has increased dramatically because of the popularisation of damage control for life‐threatening conditions, recognition and treatment of intra‐abdominal hypertension and abdominal compartment syndrome and new evidence regarding the management of severe intra‐abdominal sepsis. Although OA has saved numerous lives and has addressed many problems related to the primary pathology, this technique is also associated with serious complications. New knowledge about the pathophysiology of the OA and the development of new technologies for temporary abdominal wall closure (e.g. ABThera™ Open Abdomen Negative Pressure Therapy; KCI USA Inc., San Antonio, TX) has helped improve the management and outcomes of these patients. This review will merge expert physician opinion with scientific evidence regarding the total management of the OA.

Keywords: Abdominal compartment syndrome, Damage control, Negative pressure therapy, Open abdomen

INDICATIONS FOR THE OPEN ABDOMEN

There are three major indications for the use of the open abdomen (OA) technique: (i) damage control for life‐threatening intra‐abdominal bleeding, (ii) prevention or treatment of intra‐abdominal hypertension (IAH) and (iii) management of severe intra‐abdominal sepsis 1, 2. Although the indications and timing of management of these conditions have changed significantly in the last few years, a complete description is beyond the scope of this paper.

Damage control should be planned and executed early, before the patient reaches the ‘extremis’ stage (defined by coagulopathy, hypothermia <35°C, and severe acidosis with base deficit >15 mmol/l) taking into account the nature of the injuries, the physiologic parameters, any comorbidities and the experience of the surgeon. Attempts to restore complex injuries, such as vascular or liver injuries, in an unstable patient, should be avoided, in favour of venous ligation, temporary arterial shunting or gauze packing of the bleeding area. Following damage control, the abdomen should never be closed because of the risk of IAH. The second stage in damage control procedures involves stabilisation of the physiological parameters in the intensive care unit (ICU), followed by the final stage of definitive surgical care in the operating room, usually within 24–48 hours of the initial operation.

IAH can lead to tissue hypoperfusion, especially of the abdominal viscera, and organ dysfunction. Uncontrolled IAH exceeding 25 mmHg can cause abdominal compartment syndrome (ACS), which is a potentially lethal complication, characterised by cardiorespiratory and renal dysfunction, bacterial and toxin intestinal translocation and intracranial hypertension (1). It is essential that in high‐risk patients the intra‐abdominal pressure is routinely monitored for early diagnosis and timely therapeutic intervention. The monitoring is usually done by bladder pressure measurements, as part of standardised ICU protocols.

The role of the OA in the management of severe secondary peritonitis has been a controversial issue. There is strong clinical evidence that temporary closure of the OA using traditional passive dressings is of no benefit and may be associated with increased mortality and a higher incidence of enteroatmospheric fistulas when compared with the closed abdomen and relaparotomy on demand technique 3, 4, 5. However, recent work has suggested that the OA technique with temporary abdominal wall closure, using negative pressure dressing methods, is associated with positive outcomes 1, 2, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11.

METHODS FOR TEMPORARY ABDOMINAL WALL CLOSURE

The technique used for temporary abdominal wall closure can influence survival, complications and time to definitive fascial closure. The ideal temporary abdominal closure method should protect the abdominal contents, prevent evisceration, allow removal of infected or toxic fluid from the peritoneal cavity, prevent the formation of fistulas, avoid damage to the fascia, preserve the abdominal wall domain, make reoperation easy and safe and facilitate definitive closure 2, 11, 12, 13. The materials and techniques used for temporary closure have undergone a significant evolution over the last decade and are described below.

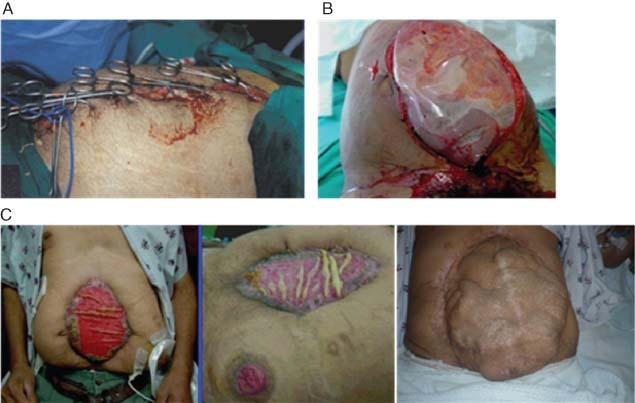

Skin approximation with towel clips or running suture has been used for a quick abdominal closure, as part of damage control in unstable patients. This technique is no longer recommended as it has been shown to lead to development of IAH or ACS (Figure 1A) 1, 2.

Figure 1.

(A) Skin approximation with towel clips. (B) Bogota Bag. (C) Absorbable mesh that often extrudes from the wound and results in an incisional hernia.

The ‘Bogota Bag’ or silo is usually constructed using a 3‐l sterile intravenous bag or a sterile X‐ray cassette cover, stapled or sutured to the skin. This technique served an important mission in the prevention or treatment of IAH or ACS; however, the Bogota Bag has now been abandoned by most modern trauma centres in favour of new, more effective methods. The Bogota Bag does not allow the effective removal of excessive fluid in bowel oedema or of toxin and cytokine‐rich intra‐abdominal fluid. In addition, this technique does not prevent the loss of abdominal wall domain (Figure 1B) 14, 15.

Absorbable synthetic meshes [Dexon™ (Tyco Healthcare, North Haven, CT), Vicryl] have been used by some surgeons to encourage granulation tissue formation and subsequent coverage with skin grafting. Synthetic meshes play a limited role, because they may not prevent IAH or ACS, do not effectively drain effectively intra‐abdominal fluid, and cannot be used in the presence of abdominal sepsis. Synthetic meshes are also associated with a high incidence of enteroatmospheric fistulas, extrusion of parts of the mesh and a high incidence of incisional hernia (Figure 1C) 1, 2.

At present, negative pressure therapy (NPT) techniques have become the most extensively used methods for temporary abdominal wall closure. NPT actively drains toxin or bacteria‐rich intraperitoneal fluid and has resulted in a high rate of fascial and abdominal wall closure. The two most commonly used NPT techniques are Barker's vacuum pack technique (BVPT) and Vacuum‐Assisted Closure® Therapy [V.A.C.® Abdominal Dressing System (ADS); KCI USA].

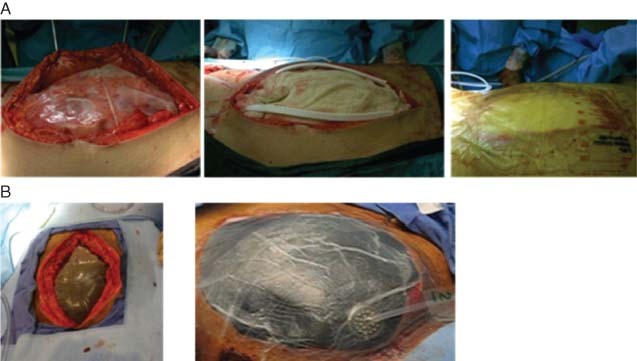

BVPT consists of a fenestrated, non adherent polyethylene sheet that is placed over the exposed bowel and under the peritoneum and covered by moist surgical towels or gauze. Two large silicone drains are then placed over the towels, and the abdominal wound is sealed with a transparent iodophor‐impregnated adhesive dressing. The drains are connected to continuous wall suction at 100–150 mmHg (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

(A) Example of Barker's vacuum packing technique. (B) Example of the Vacuum‐Assisted Closure® Abdominal Dressing System.

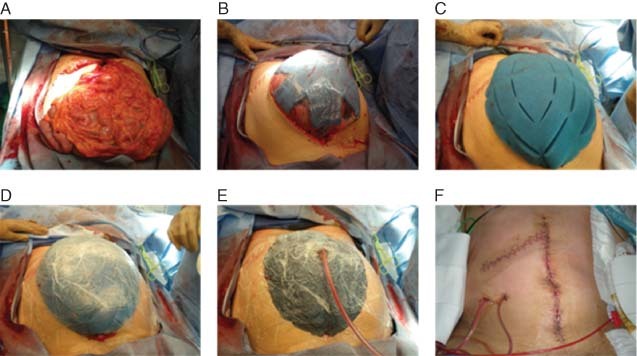

The V.A.C.® ADS is a sophisticated negative pressure dressing system (Figure 2B), which includes a polyurethane foam dressing that is covered with a protective, non adherent layer, tubing, a canister and a computerised pump. A new generation of NPT (ABThera™ OA NPT; KCI USA Inc.) for use with the OA (Figure 3A) provides a protective polyurethane foam layer composed of six strut arms, embedded between two fenestrated, non adherent sheets for easier placement around the bowel and under the peritoneum (Figure 3B). A second foam dressing is placed over the protective foam layer (Figure 3C) and covered with a semi‐occlusive adhesive drape (Figure 3D). A small piece of the adhesive drape and underlying foam are excised and an interface pad with a tubing system is applied over this defect and connected to an NPT unit (Figure 3E). The negative pressure collapses the foam, exerting medial traction and approximation of the fascia and abdominal wall. A pump canister collects and quantifies the fluid evacuated from the abdomen. Dressing changes are usually performed every 2–3 days. In the Figure 3 case study, definitive closure was achieved 9 days after the initial operation (Figure 3F).

Figure 3.

(A) Open abdomen. (B) Polyurethane foam with six strut arms, embedded between two fenestrated non adherent sheets placed directly over the bowel and tucked under the peritoneum. (C) Perforated foam cut into size and shape is placed over the protective foam. (D) The foam is covered by a semi‐occlusive adhesive drape. (E) A small piece of the adhesive drape and underlying foam are excised and an interface pad with a tubing system is applied over this opening and connected to an NPT unit. (F) Definitive fascial and skin closure 9 days after the initial operation.

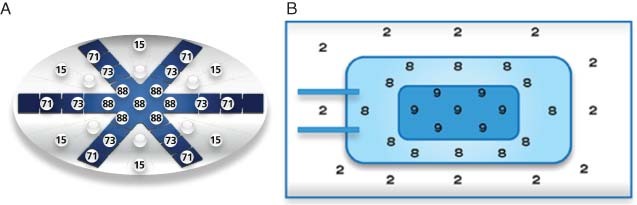

Bench studies were conducted to determine the distribution of negative pressure across the ABThera™ OA NPT and BVPT dressings. Results for the ABThera™ OA NPT showed a relatively even distribution of negative pressure in both the centre and the periphery of the foam, facilitating effective removal of any deep peritoneal fluid, reduction of bowel oedema and approximation of the abdominal wall wound (Figure 4A) (16). In contrast, with BVPT the distribution of negative pressure is highly uneven, achieving fairly high negative pressure in the centre and near zero pressure in the periphery (Figure 4B) (16).

Figure 4.

(A) Distribution of negative pressure with ABThera™ open abdomen negative pressure therapy. (B) Distribution of negative pressure with Barker's vacuum pack technique. (Reprinted with permission from KCI Licensing, Inc.)

COMPLICATIONS OF THE OPEN ABDOMEN

Although the OA has addressed some serious and potentially lethal problems related to early closure of the abdomen, this technique is also associated with significant complications, including fluid and protein loss, a catabolic state, loss of abdominal wall domain and development of enteroatmospheric fistulas (Table 1). The most serious complication is the formation of fistulas, which are difficult to control or repair. The overall incidence of this complication is about 5% 17, 18; however, in chronic OAs the incidence increases to about 15% (19). The development of a fistula increases the ICU stay by approximately threefold, the hospital stay by approximately fourfold and the hospital charges by approximately 4·5‐fold (20).

Table 1.

Complications associated with the open abdomen

| • Fluid and protein loss |

| • Catabolic state |

| • Loss of bowel function |

| • Enteroatmospheric fistulas |

| • Loss of abdominal wall domain |

| • Prolonged intensive care unit and hospital stay |

| • Increased hospital costs |

The most effective way to reduce the complications associated with the OA is to close the abdominal wall as soon as possible. This can be achieved by a combination of three strategies: (i) avoidance of excessive fluid resuscitation, (ii) use of effective NPT dressings for temporary abdominal wall closure and (iii) use of biological materials in appropriate cases for definitive fascial closure.

Restrictive fluid resuscitation in the critical patient has now become the new standard of care. Previous practices targeting ‘superoptimisation’ or ‘supranormal’ cardiac function parameters have been shown to have negative effects on the cardiorespiratory system, and to promote bowel oedema and IAH (21). Reduction of bowel oedema with a conservative fluid resuscitation increases the chances of early definitive abdominal closure.

ENTEROATMOSPHERIC FISTULAS

The development of enteroatmospheric fistulas is the most serious and challenging local complication in an OA. The exposed bowel is at risk of fistulisation, especially in a chronic OA and in the presence of synthetic meshes and infection. In some cases, numerous enteroatmospheric fistulas may develop, and the constant leak of enteric contents on the OA aggravates the inflammation and encourages the formation of new fistulas. Local control of the fistula is extremely difficult because no collection bag can be applied on the OA.

The management includes temporary local control to prevent spillage of enteric contents and prevent excoriation of the surrounding skin while planning for definitive closure of the fistula. Efforts to create a controlled fistula by inserting a Foley's catheter never succeed and usually make the fistula larger. Attempts to suture the fistula rarely succeed, unless the repair is covered by normal skin or skin graft.

Appropriate use of NPWT via V.A.C.® Therapy may be helpful in many cases and may control the spillage of intestinal contents over the surrounding exposed bowel (22). This technique cannot be used with V.A.C.® ADS and ABThera™ OA NPT. In small fistulas, the negative pressure approximates the edges of the fistula and spontaneous closure may occur. In large fistulas, the NPWT system may allow a controlled diversion of the fistula contents and protect the surrounding OA and normal skin. There are various techniques to achieve this diversion: The OA is covered by XeroForm (Covidien, Mansfield, MA) dressing, leaving the fistula orifices uncovered. A piece of foam is applied over the abdominal defect and a small hole is cut exactly over the fistula, followed by application of the polyurethane adhesive drape and connection to continuous negative suction. Lastly, a 2‐cm hole is cut on the drape and over the fistula. An ostomy bag is then applied to collect the effluent (22). A modification of this technique includes insertion of a red rubber catheter, or ‘rubber nipple’ over the opening of the fistula. At a later stage, the area around the fistula is skin grafted. A definitive surgical repair is performed, ideally 4–6 months later.

TREATMENT GOALS/OUTCOMES: DEFINITIVE FASCIAL CLOSURE

Following stabilisation of the patient, the goal is early and definitive closure of the abdomen, in order to reduce the complications associated with the OA. Closure should be achieved without tension or risk of recurrence of IAH. Primary fascial closure may be possible in many cases within a few days of the initial operation, when any intra‐abdominal packing is removed and the bowel oedema subsides.

Previous work has suggested that the OA technique with temporary abdominal wall closure using NPT as delivered by V.A.C.® ADS or ABThera™ OA NPT, is associated with positive outcomes 1, 2, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11. Although some small retrospective studies expressed concern about the possibility of increased risk of enteroatmospheric fistulas with this technique, other studies reported no increased risk 5, 23, 24. Experimental work in a peritoneal sepsis porcine model has shown that pigs treated with NPT (−125 mmHg) had reduced mortality and organ dysfunction compared to animals treated with traditional passive drainage. NPT removed significantly more peritoneal fluid, reduced systemic inflammation and improved the histopathology in the intestine, lung, liver and kidney (25).

More recently, Franklin et al. (11) reported on a 19‐patient case series documenting the use of the ABThera™ OA NPT System for management of the OA in non traumatic surgery. The majority of patients had chronic diseases, prior abdominal surgeries and at least one significant co‐morbidity, such as diabetes, hypertension or chronic renal failure. Seventeen of the 19 patients (89·5%) achieved fascial closure, which is consistent with the reported rates using NPT, and the Kaplan–Meier median time to closure was 6 days. Five patients (5/19; 26%) died during their hospitalisation, which is below the 30% mortality rate for an OA (26). The authors concluded that this new NPT system was successful in managing the OA of critically ill patients (11).

Application of ABThera™ OA NPT may help reduce the formation of adhesions between the bowel and anterior peritoneum, prevent the loss of abdominal domain and encourage the approximation of the fascial edges towards the midline. Experimental work using a swine model of intestinal ischaemia and severe sepsis, showed that early application of NPT prevented the development of IAH and subsequent multiple organ dysfunction syndrome, when compared to treatment with passive drainage (25). The suggested mechanism of protection is the removal of the peritoneal fluid containing inflammatory mediators, as shown by the reduction of the concentration of cytokines in the blood (25). These results have not yet been confirmed in human studies.

In many patients, early definitive fascial closure may not be possible because of persistent bowel oedema or intra‐abdominal sepsis. In these cases, progressive closure should be attempted at every return to the operating room, by placing a few interrupted sutures at the top and bottom of the fascial defect. Other techniques used for progressive fascial closure include a combination of NPT with a temporary mesh, sutured to the fascial edges. The mesh is tightened every few days, until the fascial defect is dominated. At this stage, the mesh is removed and the fascia is closed primarily.

All described gradual fascial approximation techniques may be used in combination with NPT, including closure via velcro or zipper‐type synthetic materials (i.e. Wittmann Patch). This technique preserves the abdominal wall domain but does not allow effective drainage of any intra‐abdominal fluid. In addition, there is a major concern that the sutures might cause ischaemic damage to the edges of the fascia, making the definitive closure operation more difficult.

In patients with persistent large fascial defects, bridging with biological material should be considered. Biologics have numerous advantages over synthetic materials. The prosthesis is incorporated into the normal tissues and becomes vascularised, is more resistant to infections, does not need to be removed if it gets infected, and maintains a satisfactory tensile strength. Acellular matrix materials, prepared from cadaver or animal skin or animal intestine, are widely available in the market. The material should always be covered by skin, usually after creating skin flaps by undermining the area lateral to the defect.

NPT: CONTRAINDICATIONS/ WARNINGS

Pressure settings should be individualised per patient. In cases with concerns about incomplete hemostasis, application of high negative pressures may aggravate bleeding. In these cases an initial low negative pressure is advisable. In addition, placing polyurethane foam directly on bowel may cause fistula formation. Extreme precaution must be taken to ensure the foam is not in contact with the bowel. Rather, a non adherent layer should be placed completely over the bowel to protect it and allow fluid egress. Also, although rare, IAH may occur in some cases during temporary abdominal wall closure. It is important that postoperatively the bladder pressure is monitored routinely during the first few hours of negative pressure dressing application.

TECHNICAL PEARLS

The following are tips in the application of NPT:

-

•

No active intra‐abdominal bleeding: start with negative pressure at −125 mmHg.

-

•

Suspicion of active bleeding due to coagulopathy and not amenable to surgical repair, consider starting with low pressures, −25 to −50 mmHg, and closely monitor output.

-

•

Postoperatively, monitor for bleeding in the canister.

-

•

Postoperatively, monitor bladder pressures for IAH.

ECONOMIC VALUE AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Studies and practice have shown that NPT helps achieve early definitive abdominal wall closure in many cases and may help reduce the serious complications associated with the open abdomen. In addition, prevention of incisional hernias eliminates the need for another major and costly operation. The concept of NPT is a relatively new and exciting field, which revolutionised the management of a complex surgical problem. The role of the NPT in other abdominal surgical pathologies, such as severe sepsis or necrotising pancreatitis, needs to be explored in future studies.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Dr DD has a consulting agreement with Kinetic Concepts, Inc. This article is part of an educational supplement funded by Kinetic Concepts Inc. to provide an overview of the V.A.C.® Therapy family of products for new users in developing markets.

REFERENCES

- 1. Kaplan M, Banwell P, Orgill DP, Ivatury RR, Demetriades D, Moore FA, Miller P, Nicholas J, Henry S. Guidelines for the management of the open abdomen. Wounds 2005;17(1 Suppl):S1–S24. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Campbell A, Chang M, Fabian T, Franz M, Kaplan M, Moore F, Reed RL, Scott B, Silverman R. Management of the open abdomen: from initial operation to definitive closure. Am Surg 2009;75(11 Suppl):S1–S22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Robledo FA, Luque‐de‐Leon E, Suarez R, Sanchez P, de‐la‐Fuente M, Vargas A, Mier J. Open versus closed management of the abdomen in the surgical treatment of severe secondary peritonitis: a randomized clinical trial. Surg Infect 2007;8:63–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Christou NV, Barie PS, Dellinger EP, Waymack JP, Stone HH. Surgical Infection Society intra‐abdominal infection study. Prospective evaluation of management techniques and outcome. Arch Surg 1993;128:193–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Adkins AL, Robbins J, Villalba M, Bendick P, Shanley CJ. Open abdomen management of intra‐abdominal sepsis. Am Surg 2004;70:137–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Garner GB, Ware DN, Cocanour CS, Duke JH, McKinley BA, Kozar RA, Moore FA. Vacuum‐assisted wound closure provides early fascial reapproximation in trauma patients with open abdomens. Am J Surg 2001;182:630–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Suliburk JW, Ware DN, Balogh Z, McKinley BA, Cocanour CS, Kozar RA, Moore FA, Ivatury RR. Vacuum‐assisted wound closure achieves early fascial closure of open abdomens after severe trauma. J Trauma 2003;55:1155–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Miller PR, Thompson JT, Faler BJ, Meredith JW, Chang MC. Late fascial closure in lieu of ventral hernia: the next step in open abdomen management. J Trauma 2002;53:843–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kaplan M. Negative pressure wound therapy in the management of abdominal compartment syndrome. Ostomy Wound Manage 2004;50:(11A Suppl):20S–5S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brace JA. Negative pressure wound therapy for abdominal wounds. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2007;34:428–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Franklin ME, Alvarez A, Russek K. Negative pressure therapy: A viable option for general surgical management of the open abdomen. Surg Innov. 2012. Jan 5. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stonerock CE, Bynoe RP, Yost MJ, Nottingham JM. Use of a vacuum‐assisted device to facilitate abdominal closure. Am Surg 2003;69:1030–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vertrees A, Shriver C. Management of the open abdominal wound. In: Sen CK, editor. Advances in wound care, 1st edn. New Rochelle: Mary Ann Liebert, Inc,2010:38–43. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rutherford EJ, Skeete DA, Brasel KJ. Management of the patient with an open abdomen: techniques in temporary and definitive closure. Curr Probl Surg 2004;41:821–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Aydin C, Aytekin FO, Yenisey C, Kabay B, Erdem E, Kocbil G, Tekin K. The effect of different temporary abdominal closure techniques on fascial wound healing and postoperative adhesions in experimental secondary peritonitis. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2008;393:67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sammons A, Delgado A, Cheatham ML. In‐vitro pressure manifolding distribution evaluation of the Abthera open abdomen negative pressure therapy system, V.A.C. abdominal dressing system, and Barker's vacuum‐pack technique, conducted under dynamic conditions. [Abst P 078]. Poster presented at the Clinical Symposium on Advances in Skin & Wound Care; 2009 Oct 22–25; San Antonio (TX), 2009.

- 17. Barker DE, Kaufman HJ, Smith LA, Ciraulo DL, Richart CL, Burns RP. Vacuum pack technique of temporary abdominal closure: a 7‐year experience with 112 patients. J Trauma 2000;48:201–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Smith LA, Barker DE, Chase CW, Somberg LB, Brock WB, Burns RP. Vacuum pack technique of temporary abdominal closure: a four‐year experience. Am Surg 1997;63:1102–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Teixeira PG, Salim A, Inaba K, Brown C, Browder T, Margulies D, Demetriades D. A prospective look at the current state of open abdomens. Am Surg 2008;74:891–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Teixeira PG, Inaba K, Dubose J, Salim A, Brown C, Rhee P, Browder T, Demetriades D. Enterocutaneous fistula complicating trauma laparotomy: a major resource burden. Am Surg 2009;75:30–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Balogh Z, McKinley BA, Cocanour CS, Kozar RA, Valdivia A, Sailors RM, Moore FA. Supranormal trauma resuscitation causes more cases of abdominal compartment syndrome. Arch Surg 2003;138:637–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Goverman J, Yelon JA, Platz JJ, Singson RC, Turcinovic M. The “Fistula VAC,” a technique for management of enterocutaneous fistulae arising within the open abdomen: report of 5 cases. J Trauma 2006;60:428–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Perez D, Wildi S, Demartines N, Bramkamp M, Koehler C, Clavien PA. Prospective evaluation of vacuum‐assisted closure in abdominal compartment syndrome and severe abdominal sepsis. J Am Coll Surg 2007;205:586–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wondberg D, Larusson HJ, Metzger U, Platz A, Zingg U. Treatment of the open abdomen with the commercially available vacuum‐assisted closure system in patients with abdominal sepsis: low primary closure rate. World J Surg 2008;32:2724–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kubiak BD, Albert SP, Gatto LA, Snyder KP, Maier KG, Vieau CJ, Roy S, Nieman GF. Peritoneal negative pressure therapy prevents multiple organ injury in a chronic porcine sepsis and ischemia/reperfusion model. Shock 2010;34:525–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Boele van Hensbroek P, Wind J, Dijkgraaf MG, Busch OR, Carel Goslings J. Temporary closure of the open abdomen: a systematic review on delayed primary fascial closure in patients with an open abdomen. World J Surg 2009;33:199–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]