Abstract

Recent research has started to identify mood disorders and problems associated with acute and chronic wounds, which have been shown to contribute to delayed healing, poor patient well‐being and a reduced quality of life. Furthermore, mood disorders have been shown to have a negative impact on financial costs for service providers and the wider society in terms of treatment and sickness absence. This study aimed to survey a multinational sample of health professionals to explore their perspective and awareness of mood disorders amongst acute and chronic wound patients. Responses were received from n = 908 health professionals working in Asia, Africa, Australia, Europe, North America and South America. A strong awareness of the prevalence of mood disorders appeared to be widespread among the health professionals across the world, in addition to a view on the potential factors contributing to these problems with mood. Despite this, it was thought that few patients were actually receiving treatment for their mood disorders. Implications for clinical practice include the need for health professionals to engage actively with their patients to enable them to learn from their experiences. Studies that explore the benefits of treatments and techniques appropriate for minimising mood disorders in patients with wounds would provide empirical evidence for health professionals to make recommendations for patients with acute and chronic wounds.

Keywords: Acute, Chronic, Health professional, Mood disorders, Wounds

Introduction

Mood disorders reflect how an individual believes, behaves and perceives situations. Problems with mood or mental illness are usually defined as a psychological pattern, often resulting in behaviour that is associated with distress, helplessness, despair and sadness 1. Furthermore, individuals suffering from mood disorders can also experience sleep disturbance, changes in appetite and chronic fatigue. As a result, mood disorders make it difficult for individuals to carry out daily tasks, which would normally be effortless for people who do not suffer from such problems 2. Mood disorders place substantial clinical, social and economic burdens on individuals suffering from these conditions, as well as on their families, friends and the wider society 3. Although specific psychological disorders are recognised using the DSM IV, many health professionals in wound care are not necessarily able to make diagnoses using such criteria. Therefore, for the purpose of this study, the term ‘mood disorder’ is also used to refer to problems with mood such as stress and anxiety, which can often be observed via interactions with patients. As well as the negative impact of mood disorders in patients, including well‐being and quality of life, they also have negative consequences for health professionals and organisations due to the financial costs associated with both sickness absence and treatment.

Mood disorders are amongst the most burdensome conditions worldwide 4. In 2004, the World Health Organization (WHO) conducted a multinational mental health survey and found that mood and anxiety disorders were prevalent across the globe 5. Problems with mood were identified in all 14 countries surveyed in the Americas, Europe, the Middle East, Africa and Asia, with the most prevalent in the USA (26·4%), European countries including Ukraine (20·5%) and France (18·4%), and the Middle East (16·9%). In particular, a substantial number of individuals reporting mood problems were not receiving treatment for their disorder, leaving symptoms unresolved for prolonged periods of time.

As a result of reports surrounding the prevalence of mood disorders, many researchers have also focused on their general financial impact. Although not specific to patients with wounds, in Europe the annual cost of mood disorders to health care services was estimated to be €113·41 billion in 2010 6. The financial burden of depressive disorders in the UK was calculated in excess of £9 billion in 2000, with £370 million directly related to treatment costs 7. Moreover, Young et al. 8 estimated the annual cost of bipolar disorders to be £342 million in the UK in 2009/2010. In the USA, it was estimated that 96·2 million workdays are lost and $14·1 billion salary‐equivalent lost productivity per year associated with bipolar disorders and 225 million workdays and $36·6 billion salary‐equivalent lost productivity per year associated with depressive disorders 9. Similar estimates have been calculated in Australia, with the overall cost of mood disorders at approximately $3·97–$4·95 billion 10, and Canada where approximately $5·5 billion is spent on mental health services each year 11. Overall, wound patients with unresolved mood disorders as a result of their condition may be contributing significantly to this financial burden.

The economic costs of untreated mood disorders in acute and chronic wounds and diagnosing, misdiagnosing and inappropriate treatment of anxiety disorders are increasingly well known, despite being largely avoidable. However, it has been thought that the financial cost on individual countries could be reduced with more widespread awareness and recognition of mood disorder symptoms, and appropriate interventions 2.

Recent studies have begun to show that patients with acute and chronic wounds experience stress and anxiety as a result of their condition 12, 13, 14, with many studies demonstrating that mood disorders can contribute to delayed healing 13, 15, 16. In particular, research involving experimentally induced biopsy wounds, surgical wounds and chronic wounds has demonstrated the relationship between stress and delayed wound healing 17. Therefore, it has been suggested that it is important for health professionals to raise awareness of the impact of mood disorders on patients with acute and chronic wounds to prevent prolonged healing rates and promote patient well‐being. Studies have also shown that patients living with long‐term wounds often have poor psychological well‐being and a reduced quality of life 18. Mood disorders contribute significantly to this negative experience for wound patients, as well as other factors, such as reduced mobility, sleep disturbance and pain.

A key factor in acknowledging and initiating diagnosis of wound‐related mood disorders are health professionals involved in wound care themselves. Previous research has focused on a health professional perspectives of mood disorders amongst patients with wounds to establish awareness of such problems 2, 19. Findings of surveys such as these demonstrate awareness of mood disorders in specific contexts, however despite this; treatment for mood is often not being received by patients.

In light of this, this study aimed to gain a multinational health professional perspective to explore the awareness and understanding of mood disorders amongst patients with wounds across the world.

Methods

This study adopted a questionnaire survey design in order to explore the mood problems and disorders experienced by patients with acute and chronic wounds from the perspective of their health professionals. The survey was sent to an opportunity sample of 5000 health professionals involved in wound care, including educators, nurses, doctors, podiatrists/chiropodists, occupational therapists, physiotherapists, dieticians, social workers, enterostomal therapists and medical company representatives working in Australia, Asia, Europe, North America, South America and Africa. Participants were contacted using a database of health professionals developed by a member of the research team. Health professionals included in the database had given their details voluntarily at conferences and related events, giving permission to be contacted with requests to participate in such studies. Health professionals were not asked to make clinical judgements on mood disorders, rather they were asked to comment on patients' symptoms based on their clinical experience. Therefore specific DSM IV classifications and diagnoses were not used for the purpose of this study.

Health professionals were invited to complete the questionnaire survey online. The survey included 16 items regarding the prevalence of mood problems and disorders among patients with chronic and acute wounds. The items were developed by the authors for the purpose of this study, based on a review of the current literature 17, and a clinical study of stress and wound healing 20. Mood problems included feeling helpless, loss of interest in daily tasks, anxiety, fatigue, irritability, self‐loathing, concentration problems, suicidal thoughts, insomnia and sleep disturbance.

Health professionals were required to estimate the prevalence of a variety of mood symptoms and disorders among their patients on a 5‐point rating scale of 0% (no patients) to 100% (all patients), based on their interactions with patients and observations of their behaviour, as well as drawing on their knowledge of patients' current treatments. Responses were based on health professionals' interactions and observations of patients.

Items also required health professionals to report the average number of patients treated per week, the types of wounds their patients suffer from, the types of wound dressings/treatments frequently used and factors they believed may be contributing to mood problems and disorders.

Descriptive statistics, including frequencies, means and standard deviations, were obtained from the questionnaire survey data using statistics package SPSS (v17, IBM).

Results

Data from the questionnaire survey were obtained from 908 health care practitioners and representatives working across the world, resulting in a response rate of 18·2%. The majority of responses were received from North America (n = 748, 82·4%), in particular Nurses working in Canada (76·7%) (Table 1). Overall, Podiatrists (m = 33·06, SD = 32·46) and Doctors (m = 28·6, SD = 36·91) were reported to be treating the most patients requiring wound care each week (Table 2).

Table 1.

Number of health professionals who responded to the survey by country and profession

| Continent/Country | Educator | Nurse | Doctor | Podiatrist | O.T. | Physio | Dietitian | Social worker | E.T. | Company | Total (n) | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | 5 | 26 | 7 | 4 | — | — | — | — | — | — | 42 | 4·6 |

| Australia | 5 | 22 | 7 | 4 | — | — | — | — | — | — | 38 | 4·2 |

| New Zealand | — | 4 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 4 | 0·4 |

| Asia | 5 | 22 | 4 | 4 | — | — | — | — | — | — | 39 | 4·2 |

| China | — | 2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 2 | 0·2 |

| Iran | 2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 2 | 0·2 |

| Japan | 3 | — | 2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | 2 | 7 | 0·8 |

| Malaysia | — | 8 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 8 | 0·9 |

| Qatar | — | 4 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 4 | 0·4 |

| Saudi Arabia | — | 2 | — | 4 | — | — | — | — | — | — | 6 | 0·7 |

| Singapore | — | 4 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 4 | 0·4 |

| Thailand | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 2 | 2 | 0·2 |

| UAE | — | 2 | 2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 4 | 0·4 |

| Europe | 16 | 30 | 22 | 4 | — | — | — | — | — | — | 72 | 7·9 |

| Belgium | — | 2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 2 | 0·2 |

| Cyprus | — | — | 2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 2 | 0·2 |

| Denmark | — | 2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 2 | 0·2 |

| France | — | — | 4 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 4 | 0·4 |

| Germany | 2 | 2 | 2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 6 | 0·7 |

| Ireland | 2 | 2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 4 | 0·4 |

| Italy | — | — | 4 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 4 | 0·4 |

| The Netherlands | — | — | 2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 2 | 0·2 |

| Poland | — | — | 2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 2 | 0·2 |

| Spain | 2 | 2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 4 | 0·4 |

| Sweden | — | 4 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 4 | 0·4 |

| Switzerland | 2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 2 | 0·2 |

| Turkey | 2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 2 | 0·2 |

| UK | 6 | 16 | 6 | 4 | — | — | — | — | — | — | 32 | 3·5 |

| North America | 32 | 542 | 68 | 22 | 14 | 30 | 2 | 2 | 30 | 6 | 748 | 82·4 |

| Canada | 26 | 480 | 48 | 20 | 14 | 22 | 2 | 2 | 30 | 6 | 650 | 71·6 |

| Mexico | — | — | 2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 2 | 0·2 |

| Puerto Rico | — | 2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 2 | 0·2 |

| USA | 6 | 60 | 18 | 2 | — | 8 | — | — | — | — | 94 | 10·4 |

| South America | 2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 2 | 0·4 |

| Brazil | 2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 2 | 0·2 |

| Africa | — | 4 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 4 | 0·4 |

| South Africa | — | 4 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 4 | 0·4 |

| Total (n) | 60 | 626 | 100 | 34 | 14 | 30 | 2 | 2 | 30 | 10 | n = 908 | 100% |

OT, occupational therapist; ET, enterostomal therapist.

Table 2.

Health professionals and the number of patients treated each week, by profession

| Profession | n | % | Mean no. patients treated per week | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nurse | 627 | 68·9 | 15·49 | 19·36 |

| Doctor | 101 | 11 | 28·6 | 36·91 |

| Educator | 59 | 6·6 | 10·33 | 17·71 |

| Podiatrist | 34 | 3·7 | 33·06 | 32·46 |

| Physiotherapist | 30 | 3·3 | 13·93 | 13·18 |

| Enterostomal therapist | 30 | 3·3 | 17·2 | 7·39 |

| Occupational therapist | 14 | 1·5 | 5·43 | 5·43 |

| Company representative | 9 | 1·1 | 7·2 | 7·84 |

| Social worker | 2 | 0·2 | 4 | 0·0 |

| Dietitian | 2 | 0·2 | 3 | 0·0 |

| Total | 908 | 100 | n = 15 394 | — |

Overall, all health professionals were treating patients with a variety of different wound aetiologies including, pressure ulcers, venous leg ulcers, arterial leg ulcers, diabetic foot ulcers, mixed aetiology wounds, wounds related to trauma, post infection wounds (e.g. cellulitis), burns and scalds, and ‘other’ wounds (e.g. abscesses, pyoderma and insect bites).

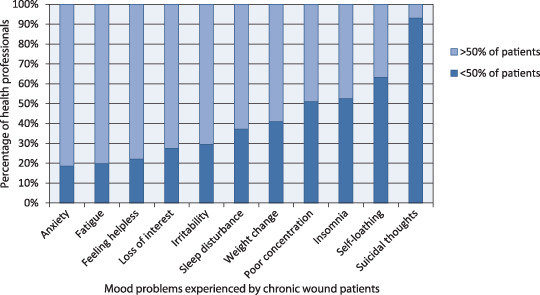

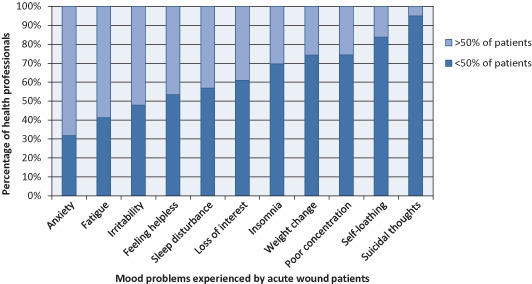

When asked to estimate the prevalence of mood problems and disorders amongst chronic wound patients, the majority of health professionals as a whole (61·8%) reported between 25% and 50% were suffering from mood disorders. In contrast, 51·8% of health professionals believed that fewer of their acute wound patients were suffering from problems with mood, estimating up to 25% of patients. Overall, health professionals reported anxiety (81·5%), fatigue (80·2%) and loss of interest (78%) as the most common symptoms of mood problems for patients with chronic wounds (Figure 1). Anxiety (68·2%), fatigue (58·8%) and loss of interest (46·6%) symptoms were also reported to be most common for acute wound patients; however, the estimated prevalence was lower for patients with chronic wounds (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Health professional's perspective of the proportion of chronic wound patients suffering from symptoms of mood disorders.

Figure 2.

Health professional's perspective of the proportion of acute wound patients suffering from symptoms of mood disorders.

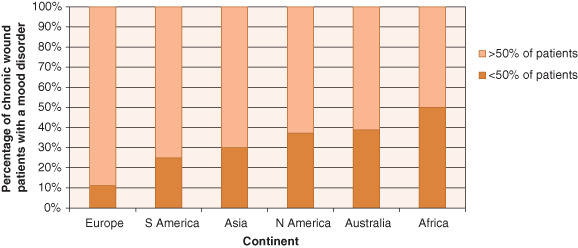

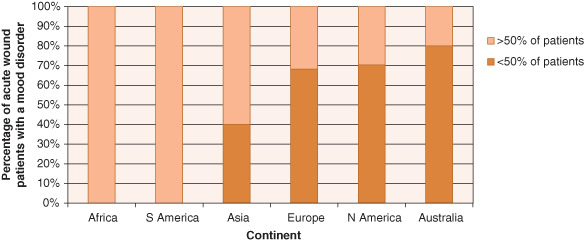

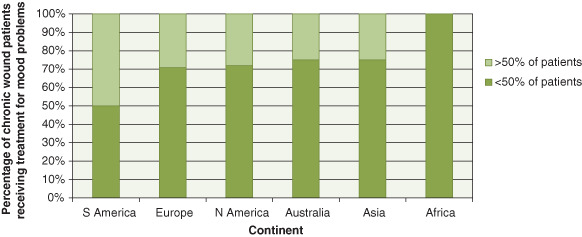

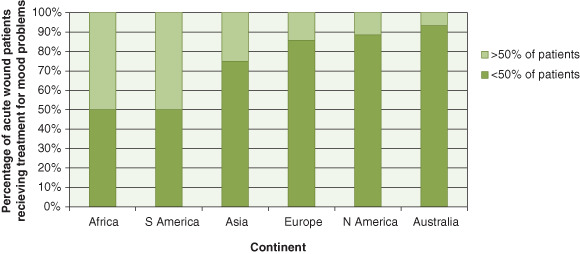

When looking at the estimated prevalence of mood problems in different countries, 88·9% of health professionals from Europe reported the highest prevalence of mood disorders amongst chronic wound patients (Figure 3), whereas health professionals in Africa and South America reported a higher prevalence of mood problems amongst their patients with acute wounds (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Health professionals' perspective of patients with chronic wounds suffering from a mood disorder, by region.

Figure 4.

Health professionals' perspective of patients with acute wounds suffering from a mood disorder, by region.

Despite these findings, health professionals estimated few patients to be receiving treatment for their mood problems. Overall, 72·4% of health professionals believed either few (25%) or none (0%) of their chronic wound patients were receiving treatment for their mood problems and disorders. Similarly, 96·5% of health professionals perceived fewer than 25% of their patients with acute wounds were receiving mood disorder treatment. Estimations for patients receiving treatment for mood disorders across the world are presented in Figures 5 and 6.

Figure 5.

Health professionals' perspective of patients with chronic wounds receiving treatment for mood disorders, by region.

Figure 6.

Health professionals' perspective of patients with acute wounds receiving treatment for mood disorders, by region.

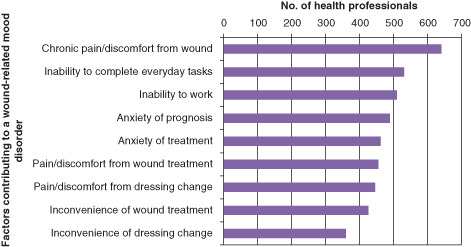

As part of the survey, it was also found that health professionals believed a number of factors to be contributing to their patients' wound‐related mood disorders. Chronic pain or discomfort from the wound was reported most frequently by health professionals (n = 641) as a major cause of mood problems amongst patients. Other examples included the inability to complete everyday tasks (n = 531), the inability to work (n = 511), anxiety about the prognosis (n = 490) and treatment (n = 463) of wounds, the pain and discomfort of wound treatment (n = 456), and specifically the pain caused by dressing change (n = 447) (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Health professionals' perceptions of factors contributing to wound‐related mood disorders.

As a result of this, the majority of health professionals believed that reducing chronic pain was a key factor in improving mood. For example, 94·6% felt it would reduce depression, 95·5% believed it would reduce anxiety and 96·8% indicated that a reduction in chronic pain would improve sleep. Similarly, 85·5% health professionals also believed reducing acute pain would contribute to a reduction in depression, 93·2% indicated it would improve anxiety and 96·4% stated that it would facilitate improved sleep.

Discussion

Overall, the majority of health professionals in all countries reported the presence of mood disorders amongst their patients with chronic and acute wounds, with anxiety, fatigue and loss of interest in daily tasks reported as the most common symptoms. Mood disorders were perceived to be most prevalent amongst patients with chronic wounds, in Europe, Asia and North America, whereas acute wound patients were perceived to be most affected by mood disorders in Africa and South America. This demonstrates an important awareness of mood symptoms and disorders amongst patients suffering from wounds. In particular, the perspective of patients with chronic wounds experiencing problems with mood lends support to the notion that individuals suffering from a long‐term illness, such as chronic wounds, experience mood disorders related to their condition 21. Building on findings of European‐based studies on the perspectives of health professionals 2, 19, this study demonstrates that there is a strong awareness of mood disorders across the world, indicating that health professionals can identify a variety of mood problems. However, when asked about treatment for mood, the majority of health professionals in all countries reported few patients (<25%) if any were receiving any treatment for their observed symptoms. Specifically, 72·4% of respondents stated that less than a quarter of their chronic wound patients were receiving treatment for this. Similar findings were established for patients with acute wounds, with 96·5% of health professionals reporting that the majority of acute wound patients were also not receiving treatment for their mood disorder symptoms. These findings show that, while health professionals are aware of the behavioural signs of mood problems and disorders among their patients, little is being performed to formally assess and treat patients for these conditions. The most common symptoms reported by health professionals in this survey, such as anxiety, fatigue and a loss of interest in daily tasks, can often be managed by encouraging patients to articulate their feelings and educating them in the use of coping strategies and social support networks 22. Types of treatments for mood disorders often include educating patients in coping strategies and creating a relaxing and comfortable environment for patients.

In line with previous research, it was apparent that health professionals believed pain to be a major contributing factor to the mood disorders experienced by acute and chronic wound patients. Moreover, chronic pain and discomfort of the wound was thought to be a significant cause of mood problems and disorders, reflecting findings of several studies that demonstrate the relationship between pain and stress in wound care 20, 23, 24. Furthermore, patients experience a lack of control over their wound treatment, as it restricts their daily activities and routines over a long period of time. These findings also support research that demonstrates how patients with wounds often have a reduced quality of life 18, as it was found that health professionals believed that their patients mood disorders were also a result of the inability to complete everyday tasks, the inability to work, and confusion and anxiety surrounding the prognosis of their illness.

As pain and discomfort of wounds was highlighted as a significant contributor to mood disorders in this survey, it is recommended that pain management should be an important aspect of routine wound treatment. Recent research has shown that minimising pain can help to minimise stress and anxiety, which will subsequently improve patients' quality of life and promote wound healing 20, 21, 24. Therefore, wherever possible, it is suggested that health professionals should assess and manage pain regularly during wound treatment. Specifically, pain management should be implemented to individual patients' needs, for example drug therapies such as analgesics, or non‐drug therapies such as appropriate dressing selection and distraction and relaxation techniques 25.

Selection of appropriate dressings is often associated with pain management and research has shown certain dressingsto significantly reduce pain when they are removed and reapplied 16. The World Union of Wound Healing Societies (WUWHS) 26 consensus document on pain at wound dressing change also stresses the importance of selecting appropriate dressings, such as non‐traumatic dressings and dressings that offer pain‐free removal. Wound dressings such as alginate, film, foam, hydrocolloid and hydrogel have all been reported to cause pain and tissue trauma during dressing changes 27, which have been shown to contribute to stress and anxiety 17, 28. However, the introduction of atraumatic dressings (e.g. Safetac adhesive technology, Mölnlycke Health Care Gothenburg, Sweden) has demonstrated a significant reduction in pain and stress 29. Reducing wound pain and dressing‐related pain could lend to an improvement in the resulting mood problems and disorders experienced by patients. For example, if dressings are selected that promote pain‐free removal, patients would experience a reduction in pain‐induced stress and anxiety. It is also suggested that stress and anxiety should be routinely measured as part of wound care in order to identify patients suffering from mood disorders more easily and to enable implementation of effective treatment.

Our findings show that the majority of health professionals agreed that reducing acute and chronic wound pain would improve mood disorder symptoms, including depression, anxiety and sleep disturbance. It is suggested therefore that health professionals need to engage actively with their patients to enable them to learn from their experiences. Although health professionals are accountable for their practice, ethical and professional tensions are thought to occur if unnecessary pain is inflicted on patients as a result of dressing‐related procedures. Therefore, it is recommended that if the patient with a wound, rather than the professional, is central to the assessment process these issues can be resolved more easily 30.

Future research could benefit from exploring mood problems and disorders from the patient's perspective to enable a comparison with the estimations of health professionals. For example, qualitative research would contribute to health professionals' understanding of the patient experience of wound care, with a particular focus on mood disorders experienced as a result of this particular condition. Moreover, studies that explore the benefits of treatments and techniques appropriate for minimising mood disorders in patients with wounds would provide empirical evidence for health professionals to make recommendations for patients with acute and chronic wounds. The prevention of mood disorders by building trusting relationships with patients and successful pain management should therefore be seen as a priority in wound care.

Limitations

Although this exploratory study provides a basis for future research to explore the prevalence of mood disorders among wound patients in more depth, there were a number of limitations associated with the study design. Health professionals who took part in the survey were asked to estimate the number of patients suffering from mood disorders based on observations and interactions with their patients. Therefore, their estimations about the number of patients suffering from mood disorders could be accurate based on their involvement and knowledge of the patients' treatment for such problems, or could be purely speculative.

In addition to this, the study design involved a large convenience sample of health professionals obtained via database of contacts which that resulted in unequal numbers of respondents from different countries, as well ambiguity regarding the demographics of health professionals who declined to complete the survey. The database was set up in North America, which could explain the larger numbers of respondents from this region in comparison with other countries. The frequency of visits and interactions that health professionals have with their acute versus chronic wound patients are also difficult to compare given the unequal sample size.

Although health professionals reported their perception of the proportion of patients receiving treatment for mood problems and disorders, due to the nature of the survey, it is unknown whether health professionals were aware of actual treatment being received, based on the patient files, or whether their perceptions were speculative. Perceptions of mood problems may be influenced by the length of the clinical relationship between health professionals and patients, which would differ on an individual case basis.

Finally, due to the exploratory nature of this study, the questionnaire items did not permit an in‐depth, correlational analysis of the data, for example to investigate relationships between wound types, specific mood disorders and country of origin. The purpose of this study was to conduct a broad exploration of health professionals' awareness of mood disorders; therefore, future studies that include clinical interviews and use more detailed statistical analysis would be more appropriate to investigate this further. In particular, the differences between groups in this study could be confirmed using methods that are able to obtain equal responses across all countries.

Conclusion

Previous research and the perspective of the health professionals who responded to this survey demonstrate a shared opinion that successful assessment and management of mood disorders and pain during wound care might contribute significantly to a reduction in mood disorders and problems among patients with acute and chronic wounds. A strong awareness of the prevalence of mood disorders and the impact of pain appears to be widespread among the health professionals across the world who responded to this survey. Despite this, it was thought that the majority of patients did not appear to be receiving treatment for their mood disorders, which is detrimental to their psychological well‐being and overall wound healing. If the majority of patients with wounds also experience mood problems and disorders, then this can significantly increase the cost of wound care. This reinforces the importance of routinely assessing and managing pain and mood disorders as this will not only help to improve patients' overall quality of life but also reduce the financial burden on health service providers.

Acknowledgements

There are no conflicts of interest to declare and no funding was received to conduct this survey.

References

- 1.Ghaemi SN. Mood disorders: a practical guide. London: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2008.

- 2. Upton D, Hender C, Solowiej K. Mood disorders in patients with acute and chronic wounds: a health professional perspective. J Wound Care 2012;21:42–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Patel A. The cost of mood disorders. Psychiatry 2006;5:141–5. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wang PS, Kessler RC. Global burden of mood disorders. In: Schatzberg AF, editor. The American psychiatric publishing book of mood disorders. Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing Inc, 2006:55–66. [Google Scholar]

- 5. World Health Organization (WHO) . Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization, world mental health surveys. J Am Med Assoc 2004;291:2581–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chidambaram A. Management of mood disorders, the greatest economic burden to European healthcare. http://www.frost.com/prod/servlet/market‐insight‐top.pag?docid=256666223 [accessed on 5 April 2012].

- 7. Thomas CM, Morris S. Cost of depression among adults in England 2000. Br J Psychiatry 2003;183:514–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Young AH, Rigney U, Shaw S, Emmas C, Thompson JM. Annual cost of managing bipolar disorder to the UK healthcare system. J Affect Disord 2011;133:450–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kessler RC, Akiskal HS, Ames M, Birnbaum H, Greenberg P, Hirschfield RMA, JIN R, Merikangas KR, Wang PS. Prevalence and effects of mood disorders on work performance in a nationally representative sample of U.S. workers. Am J Psychiatry 2006;163:1561–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fisher LJ, Goldney RD, Dal Grande E, Taylor AW, Hawthorne G. Bipolar disorders in Australia, a population‐based study of excess costs. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2007;42:105–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mood Disorders Society of Canada. Mental Illness in Canada. 2009; http://www.mooddisorderscanada.ca/ [accessed on 5 April 2012].

- 12. Cole‐King A, Harding KG. Psychological factors and delayed healing in chronic wounds. Psychosom Med 2001;63:216–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ebrecht M, Hextall J, Kirtley LG, Taylor A, Dyson M, Weinman J. Perceived stress and cortisol levels predict speed of wound healing in healthy male adults. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2004;29:798–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jones J, Barr W, Robinson J, Carlise C. Depression in patients with chronic venous leg ulceration. Br J Nurs 2006;15:S17–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Marucha PT, Kiecolt‐Glaser J, Favagehi M. Mucosal wound healing is impaired by examination stress. Psychosom Med 1998;60:362–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. White R. A multinational survey of the assessment of pain when removing dressings. Wounds UK 2008;4:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Solowiej K, Mason V, Upton D. Review of the relationship between stress and wound healing: part 1. J Wound Care 2009;18:357–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Beitz JM, Goldberg E. The lived experience of having a chronic wound: a phenomenologic study. Medsurg Nurs 2005;14:52–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Price PE, Fagervik‐Morton H, Mudge E, Beele H, Ruiz JC, Nystrøm TH, Lindholm C, Maume S, Melby‐Østergaard B, Peter Y, Romanelli M, Seppänen S, Serena TE, Sibbald G, Soriano JV, White W, Wollina V, Woo KY, Wyndham‐white C, Harding KG. Dressing‐related pain in patients with chronic wounds: an international perspective. Int Wound J 2008;5:159–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Upton D, Solowiej K, Hender C, Woo KY. Stress and pain associated with dressing change in chronic wound patients. J Wound Care 2012;21:53–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Walburn J, Vedhara K, Hankins M, Rixon L, Weinman J. Psychological stress and wound healing in humans: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Psychosom Res 2009;67:253–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Solowiej K, Mason V, Upton D. Assessing and managing stress and pain in wound care: part 2, a review of pain and stress assessment tools. J Wound Care 2010;19:56–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Flanagan M. Managing chronic wound pain in primary care. Practice Nurse 2006;31:34–7. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Woo K, Sibbald G, Fogh K, Glynn C, Krasner D, Leaper D, Osterbrink J, Price P, Teot L. Assessment and management of persistent (chronic) and total wound pain. Int Wound J 2008;5:205–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Solowiej K, Mason V, Upton D. Psychological stress and pain in wound care, part 3: management. J Wound Care 2010b;19:153–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. World Union of Wound Healing Societies (WUWHS) . Principles of best practice: minimising pain at wound dressing‐related procedures. A consensus document. London: MEP Ltd, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hollinworth H, Collier M. Nurses' views about pain and trauma at dressing changes: results of a national survey. J Wound Care 2000;9:369–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Richardson C, Upton D. Managing pain and stress in wound care. Wounds UK 2011;7:100–7. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Davies P, Rippon M. Evidence review: the clinical benefits of Safetac technology in wound care. London: MA Healthcare Ltd, 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hollinworth H. Pain at wound dressing‐related procedures: a template for assessment. Retrieved 22 April 2012, from: http://www.worldwidewounds.com/2005/august/Hollinworth/Framework‐Assessing‐Pain‐Wound‐Dressing‐Related.html