Abstract

Chronic osteomyelitis associated with soft‐tissue defect following surgical management is a severe complication for orthopaedic surgeons. Traditionally, the treatment protocol for the notorious complication involved thorough debridement, bone grafting, long‐term antibiotic use and flap surgery. Alternatively, platelet‐rich plasma (PRP), a high concentration of platelets collected via centrifugation, has been successfully used as an adjuvant treatment for bone and soft‐tissue infection in medical practices. PRP has numerous significant advantages, including stypsis, inflammation remission and reducing the amount of infected fluid. It increases bone and soft‐tissue healing and allows fewer opportunities for transplant rejection. Through many years of studies showing the advantages of PRP, it has become preferred organic product for the clinical treatment of infections, especially for chronic osteomyelitis associated with soft‐tissue defect. To promote the clinical use of this simple and efficacious technique in trauma, we report the case of a patient with chronic calcaneal osteomyelitis associated with soft‐tissue defect that healed uneventfully with PRP.

Keywords: Calcaneal, Chronic osteomyelitis, Platelet‐rich plasma, Soft‐tissue defect

INTRODUCTION

Chronic osteomyelitis associated with soft‐tissue defect following fracture care is disastrous. It typically requires a strategic treatment protocol that involves thorough debridement, bone grafting, long‐term antibiotics use and complex flap coverage. The long‐term nature of therapy and the need for multiple operations can cause patients to develop depression after experiencing unsatisfactory results.

Currently, platelet‐rich plasma (PRP) is recognised as an appropriate autologous biomaterial for treating chronically infected wounds. Previous studies have shown that PRP contains various growth factors, including platelet‐derived growth factor (PDGF), transforming growth factor‐p1/p2 (TGF‐p1/p2), insulin‐like growth factor (IGF), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), epidermal growth factor (EGF) and epithelial cell growth factor (ECGF) (1). Landesberg noted that PRP had an unequivocal and outstanding ability to heal wounds and repair bone, and it improves the quality of bone healing (2). Haematogenous infection diseases and rejection are unlikely to occur as PRP is completely autologous. Furthermore, PRP is easy to formulate and implement for clinical operations.

Soft‐tissue defect and chronic osteomyelitis are frequently observed following the surgical management of calcaneal fractures. Due to fragile blood circulation and chronic infection, self‐repair with dressing changes and the systemic use of antibiotics is usually ineffective. Traditionally, a local transfer flap from the calf is designed to cover the defect, and bone grafting is inevitable. This meticulous management can lead to secondary damage, and postoperative failure occasionally occurs. Alternatively, PRP's biological properties allow it to be used for chronic osteomyelitis associated with soft‐tissue defect. To encourage the clinical use of this simple and efficacious technique, we report the case of a patient with chronic calcaneal osteomyelitis associated with soft‐tissue defect that healed uneventfully with PRP. The patient was informed that all medical data may be used for possible publication.

CASE REPORT

A 58‐year‐old male fell from a height and injured both feet. He was conscious with bleeding feet and was sent to the local emergency centre immediately. Radiographic examination showed a closed fracture to the left tibia, bilateral open fractures of the calcaneus with bone defect, pelvic fracture and fractures of the first and second lumbar vertebra bodies. Thorough debridement and antibiotic therapies were provided. Under the guidance of Adult Advanced Life Support (AALS), vital signs were monitored at a local clinic. The patient was transferred to our hospital when his general condition was good. One week later, we decided to implement surgery for the multiple fractures in the lumbar vertebrae and limbs via open reduction and internal fixation. The patient gradually recovered with regular functional exercises and was capable of bearing weight with crutches 4 months postoperatively. All incisions healed completely, and only scar tissue remained.

During partial weight bearing, the patient had continuous pain in both heels. Subsequently, a lateral, L‐shaped incision in the right calcaneum started swelling and became hot, and a superficial sinus 5‐mm deep formed and began oozing thin, yellow pus. Tissues from around the wound and samples of the secretion were sent for a bacterial examination, which was Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) positive. Consequently, we decided to remove the calcaneal implants and implement a thorough debridement of the right calcaneum. Soon after, the swelling and inflammation around the infected wound decreased. After 2 weeks of dressing changes and antibiotics therapy, the patient was discharged. However, the inflammatory responses recurred 1 month later. The condition of the right calcaneum became worse, with a sinus 30‐mm wide and 40‐mm deep with yellowish pus floating out (Figure 1). A bacterial culture again confirmed a MRSA infection. Radiography and computed tomography showed that the right calcaneum was partially defective, with necrotic bones (Figure 2). Four months later, we prescribed debridement to remove the necrotic bone, lavage with vancomycin and continuous dressing change. Unfortunately, the infection returned, this time with a substantial amount of yellowish pus.

Figure 1.

Chronic osteomyelitis associated with soft‐tissue defect in the right heel. The wound formed at the lateral heel with a sinus 30‐mm wide and 40‐mm deep with yellowish pus floating out.

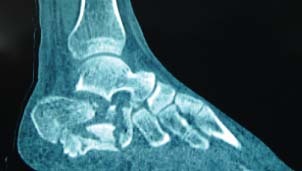

Figure 2.

Sagittal CT scan of the right calcaneus. Bone defect and decompression of the subtalar joint were present, which made thorough debridement difficult.

On the basis of our previous experience with the research and clinical application of PRP, we selected alternative treatment with PRP for the chronic infection and bone defect. The PRP was made by centrifuging the blood twice 1, 2. A 5 ml citrate phosphate dextrose was placed in an aseptic syringe for anticoagulation. Whole blood (40 ml) was drawn from the front elbow vein then placed in an aseptic tube, gently shaken and centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 10 minutes. Next, the blood in the tube was divided into three different layers and colours. The top layer consisted of platelet‐poor plasma (PPP), which is semi‐opaque and contains water, electrolytes and organic compounds. The middle layer was PRP, which has a yellowish colour, and this layer contains primarily platelets and partial white blood cells and was the desired product of this process. The bottom layer contained enriched red blood cells (RBC). Four fifths of RBCs in the lowest layer was withdrawn, and the remaining blood product was prepared for further concentration at a rotating speed of 2000 rpm for 10 minutes. Finally, the contents formed three different layers of colours, which were very similar to the result of the first centrifuging process. This time, we removed the PPP and used a syringe to withdraw the middle layer, which was ready‐to‐use PRP.

The wound was filled with 4 ml of jelly‐like PRP (Figure 3). The disease site was covered with a medical transparent membrane for daily observation. One week later, the membrane was discarded, and the sinus appeared smaller and was surrounded by fresh granulation tissue. However, the sinus' infection symptoms disappeared for only a few days, and the sinus remained. We decided to apply PRP again 1 month later. The running pus disappeared, the sinus' inflammation and dimensions decreased gradually and the wound seemed healthier; however, it did not heal perfectly. Therefore, a third PRP treatment seemed inevitable. This time, the symptoms of inflammation and pus discharged vanished thoroughly, and a healthy scar formed uneventfully (Figure 4). The patient complied with regular postoperative follow‐up. The osteomyelitis did not recur once healthy soft‐tissue coverage was established.

Figure 3.

The wound, filled with jelly‐like PRP. Following a thorough debridement, the wound was filled with PRP and then covered with a medical transparent membrane for daily observation.

Figure 4.

The healed wound. The wound healed with no recurrence of chronic infection.

DISCUSSION

Chronic osteomyelitis combined with soft‐tissue defect after surgery is one of the most severe problems that orthopaedic surgeons face. S. aureus is the most common infectious microorganism in open fracture osteomyelitis (3). Symptoms and signs of chronic osteomyelitis often appear several months after open injuries, and patients may present with a low fever, swelling, pain or a sinus with pus drainage and the formation of necrotic bone tissue. In our patient's case, all such symptoms were present. We speculated that bacteria were initially inoculated directly into the fractured calcaneum. Additionally, internal fixation devices may also contribute to infection and increase its development; therefore, implants were removed as soon as the infection presented.

For internal therapy, a preventive parenteral antimicrobial treatment should be provided to treat clinically suspected pathogens then modified once the pathogenic organism is identified. Preventive intravenous antimicrobial therapy should be provided within 6 to 8 hours after an open injury (4). In our patient's case, urgent care was provided immediately, and preventive intravenous antimicrobial therapy was started within 2 hours after the patient was sent to the first hospital. However, the preventive intravenous antimicrobial therapy did not work efficaciously. Indeed, osteomyelitis caused by trauma is extremely difficult to treat with antibiotics, and a 5‐hour delay in surgically debriding any open injuries could increase the incidence of infection (5). We undertook several bacterial cultures before and after the first debridement and obtained a result of MRSA; subsequently, direct antimicrobial therapy with vancomycin was used, but it did not work successfully again.

As initial wound care plays an important role in treating an infected wound, the patient received ongoing treatment with wound dressing changes, irrigation with prophylactic antimicrobials and other treatments aimed at reducing the drainage of pus and pathogenic organisms. In terms of surgical treatment, a critical debridement that removes all necrotic bone or soft tissue is the most efficient and is a prerequisite for osteomyelitis. The surgical management of osteomyelitis follows certain principles (4); once all the dead bone and infected tissues are removed, the species and quantity of pathogenic organisms can be further determined. Moreover, a controlled‐release, pathogen‐specific antibiotic is usually employed intraoperatively. The late debridement of the calcaneum could not thoroughly eliminate pathogens from the infection wound. Radiography showed that the normal structure of the right calcaneum was deformed and destroyed and an open cavity had formed, allowing pathogens to hide in the trabeculae.

Since the accident happened, the patient had suffered from chronic right‐foot infections accompanied by low‐grade fevers, pain, redness, swelling and pus discharge. Eventually, he was unable to bear weight on the infected foot. Before the initial PRP therapy, he underwent continuous treatment with wound dressing changes and irrigation with prophylactic antimicrobial solutions; however, the yellowish pus from the wound recurred and persisted. PRP injection therapy was performed three times to treat the chronic wound. PRP has an adjunctive function in repairing chronic wounds. It is a highly concentrated blood product made of autologous platelets obtained through centrifugation, and it contains various growth factors, such as PDGF, TGF‐p1/p2, IGF, EGF, VEGF and ECGF. These growth factors have been proven to have the ability to stimulate cell proliferation and enhance soft‐tissue repair, vessel reformation and collagen synthesis. PRP also contains a high concentration of white blood cells, which reduces inflammation responses 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11.

Greenhalgh believed that chronic wounds could decrease the quantity of growth factors available to drain inflammatory fibrin that surrounds capillaries, which restricts the amount of growth factors present in the vessel passing through from the cell wall to the wound (12). Robson showed that a long‐term chronic inflammation could increase proteolytic enzymes, which can increase the metabolism of growth factors. However, the problems mentioned above can be solved easily with PRP therapy (13).

Chronic wound healing is a complicated process that involves multiple growth factors and complex regulatory mechanisms. Studies have shown that repaired wounds treated with multi‐participation growth factors had better outcomes than those treated with single growth factors, due to collaborations and stimulations between growth factors 14, 15, 16, 17. The experiment conducted by Bielecki showed that PRP appeared to inhibit S. aureus and Colibacillus 18, 19. In addition, the autologous PRP gelatine has an anti‐infection feature. Yuan used PRP to treat chronic femoral osteomyelitis and obtained a satisfactory result (20). Our previous research showed that PRP could improve the healing of bone defects 21, 22, 23, 24.

PRP is a new, autologous biomaterial beneficial for repairing bone and soft‐tissue defects, and it has shown an excellent outcome. The use of PRP for local infection control and chronic wound repair research has provided an alternative treatment for chronic infections. Previous reports have shown PRP's advantages for controlling soft‐tissue infections. However, some investigators have reported that outcomes may not be satisfactory 25, 26. It should be noted that a critical debridement is the prerequisite for the clinical application of PRP for chronic infections. Although we found that PRP was beneficial for the treatment of calcaneal osteomyelitis, we cautiously concluded that a comprehensive treatment protocol was necessary 27, 28, 29, and PRP was an alternative that required meticulous wound care. To ensure proper treatment of osteomyelitis with PRP, extensive investigation and clinical practice is necessary to support PRP's values in treating infections, especially those associated with osteomyelitis.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The study was partially supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81071487).

REFERENCES

- 1. Anitua E. Plasma rich in growth factors: preliminary results of use in the preparation of future sites for implants. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 1999;14:529–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Landesberg R, Roy M, Glickman MS. Quantification of growth factor levels using a simplified method of platelet‐rich plasma gel preparation. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2000;58:297–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mackowiak PA, Jones SR, Smith JW. Diagnostic value of sinus‐tract cultures in chronic osteomyelitis. JAMA 1978;239:2772–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Irene G, Verbari EF. Osteomyelitis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2006;20:1065–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kindsfater K, Jonassen EA. Osteomyelitis in grade II and III open tibia fractures with late debridement. J Orthop Trauma 1995;9:121–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Anitua E, Andía I, Sanchez M, Azofra J, del Mar Zalduendo M, de la Fuente M, Nurden P, Nurden AT. Autologous preparations rich in growth factors promote proliferation and induce VEGF and HGF production by human tendon cells in culture. J Orthop Res 2005;23:281–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sun W, Lin H, Xie H, Chen B, Zhao W, Han Q, Zhao Y, Xiao Z, Dai J. Collagen membranes loaded with collagen‐binding human PDGF‐BB accelerate wound healing in a rabbit dermal ischemic ulcer model. Growth Factors 2007;25:309–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kim SJ, Kim SY, Kwon CH, Kim YK. Differential effect of FGF and PDGF on cell proliferation and migration in osteoblastic cells. Growth Factors 2007;25:77–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Claes L, Ignatius A, Lechner R, Gebhard F, Kraus M, Baumgartel S, Recknagel S, Krischak GD. The effect of both a thoracic trauma and a soft‐tissue trauma on fracture healing in a rat model. Acta Orthop 2011;82:223–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lawlor DK, Derose G, Harris KA, Lovell MB, Novick TV, Forbes TL. The role of platelet‐rich plasma in inguinal wound healing in vascular surgery patients. Vasc Endovascular Surg 2011;45:241–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Na JI, Choi JW, Choi HR, Jeong JB, Park KC, Youn SW, Huh CH. Rapid healing and reduced erythema after ablative fractional carbon dioxide laser resurfacing combined with the application of autologous platelet‐rich plasma. Dermatol Surg 2011;37:463–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Greenhalgh DG. Wound healing and diabetes mellitus. Clin Plast Surg 2003;30:37–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Robson MC. The role of growth factors in the healing of chronic wound. Wound Repair Regen 1997;5:12–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tohidnezhad M, Varoga D, Podschun R, Wruck CJ, Seekamp A, Brandenburg LO, Pufe T, Lippross S. Thrombocytes are effectors of the innate immune system releasing human beta defensin‐3. Injury 2011;42:682–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Takamiya M, Saigusa K, Aoki Y. Immunohistochemical study of basic fibroblast growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor expression for age determination of cutaneous wounds. Am J Forensic Med Pathol 2002;23:264–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Thodis E, Kriki P, Kakagia D, Passadakis P, Theodoridis M, Mourvati E, Vargemezis V. Rigorous Vibrio vulnificus soft tissue infection of the lower leg in a renal transplant patient managed be vacuum therapy and autologous growth factors. J Cutan Med Surg 2009;13:209–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Anitua E, Aguirre JJ, Algorta J, Ayerdi E, Cabezas AI, Orive G, Andia I. Effectiveness of autologous preparation rich in growth factors for the treatment of chronic cutaneous ulcers. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 2008;844:415–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bielecki TM, Gazdzik TS, Arendt J, Szczepanski T, Król W, Wielkoszynski T. Antibacterial effect of autologous platelet gel enriched with growth factors and other active substances: an in vitro study. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2007;89:417–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Carter MJ, Fylling CP, Parnell LK. Use of platelet rich plasma gel on wound healing: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Eplasty 2011;11:e38. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yuan T, Zhang C, Zeng B. Treatment of chronic femoral osteomyelitis with platelet‐rich plasma (PRP): a case report. Transfus Apheresis Sci 2007;38:167–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jia WT, Zhang CQ, Wang JQ, Feng Y, Ai ZS. The prophylactic effects of platelet‐leukocyte gel in osteomyelitis: an experimental study in a rabbit model. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2010;92:304–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhang CQ, Yuan T, Zeng BF. Experimental study on effect of platelet‐rich plasma in repair of bone defect. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Ke Za Zhi 2003;17:355–8. In Chinese. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Liu J, Yuan T, Zhang C. Three cases using platelet‐rich plasma to cure chronic soft tissue lesions. Transfus Apher Sci 2011;45:151–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yuan T, Guo SC, Han P, Zhang CQ, Zeng BF. Application of leukocyte‐ and platelet‐rich plasma (L‐PRP) in trauma surgery. Curr Pharm Biotechnol 2011. doi: 10.2174/1389211217403742010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Almdahl SM, Veel T, Halvorsen P, Vold MB, Molstad P. Randomized prospective trial of saphenous vein harvest site infection after wound closure with and without topical application of autologous platelet‐rich plasma. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2011;39:44–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Khalafi RS, Bradford DW, Wilson MG. Topical application of autologous blood products during surgical closure following a coronary artery bypass graft. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2008;34:360–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Spellberg B, Lipsky BA. Systemic antibiotic therapy for chronic osteomyelitis in adults. Clin Infect Dis 2011. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cierny G 3rd. Surgical treatment of osteomyelitis. Plast Reconstr Surg 2011;127:190S–204S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Malizos KN, Gougoulias NE, Dailiana ZH, Varitimidis S, Bargiotas KA, Paridis D. Ankle and foot osteomyelitis: treatment protocol and clinical results. Injury 2010;41:285–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]