Abstract

Chronic wounds, including diabetic foot ulcers, pressure ulcers and venous leg ulcers, represent a significant cause of morbidity in developed countries, predominantly in older patients. The aetiology of these wounds is probably multifactorial, but the role of bacteria in their pathogenesis is still unclear. Moreover, the presence of bacterial biofilms has been considered an important factor responsible for wounds chronicity. We aimed to investigate the laser action as a possible biofilm eradicating strategy, in order to attempt an additional treatment to antibiotic therapy to improve wound healing. In this work, the effect of near‐infrared (NIR) laser was evaluated on mono and polymicrobial biofilms produced by two pathogenic bacterial strains, Staphylococcus aureus PECHA10 and Pseudomonas aeruginosa PECHA9, both isolated from a chronic venous leg ulcer. Laser effect was assessed by biomass measurement, colony forming unit count and cell viability assay. It was shown that the laser treatment has not affected the biofilms biomass neither the cell viability, although a small disruptive action was observed in the structure of all biofilms tested. A reduction on cell growth was observed in S. aureus and in polymicrobial biofilms. This work represents an initial in vitro approach to study the influence of NIR laser treatment on bacterial biofilms in order to explain its potentially advantageous effects in the healing process of chronic infected wounds.

Keywords: Biofilm communities, Chronic wound, Laser irradiation, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus

INTRODUCTION

Chronic wounds, including diabetic foot ulcers, pressure ulcers and venous leg ulcers affect 1% to 2% of the population in developed countries and represent a significant cause of morbidity predominantly in patients older than 60 years 1, 2, 3.

The aetiology of these wounds is yet poorly understood; however, it is probably multifactorial. It has been shown that inflammatory and infectious processes contribute to the chronic state. Normally, the infection results from an increased host susceptibility or from an increased microbial concentration and virulence of the strain, although both factors might be present (4).

The role played by microorganisms in chronic non healing wounds is still not entirely known (5). The microbial bioburden, the microbial species and the biofilm formation within the wound are important factors that can delay the healing process. Although it is widely accepted and well documented that both acute and chronic wounds are more susceptible to infection when the bioburden within the wound bed reaches a ‘critical level’6, 7, 8, recent studies have shown that bacteria are randomly distributed within the wound and consequently the assessment of the true microbial density in a wound is often biased 3, 4.

It is known that the microflora of chronic wounds comprises multiple species. Different bacterial profiling studies using standard culturing 9, 10, 11, 12 and modern molecular microbiological methods 13, 14, 15, 16 have documented that predominant microorganisms in chronic wounds include Staphylococcus spp., Pseudomonas spp., Streptococcus spp., Enterococcus spp., Corynebacterium spp. and various anaerobes and suggest that the specificity of microorganisms is more important than bacterial bioburden to delay or even prevent the healing process.

Most of the chronic wound pathogens, such as Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, are typical biofilm producers 17, 18. The presence of P. aeruginosa biofilm in wounds has been recently documented and considered as an important factor responsible for wounds chronicity 19, 20, 21. Bacteria in biofilm communities show significantly greater resistance to traditional antimicrobial therapies than their planktonic counterparts, therefore removing biofilm may be important in the management of chronic wounds and new biofilm eradication strategies to treat chronic wounds are demanded 22, 23, 24, 25.

Currently, laser therapy to improve wound healing opens a new perspective in this research area (26). Laser irradiation can enhance the release of growth factors from fibroblasts and stimulate the wounded cells to recover their functions and increase their in vitro proliferation 27, 28.

Although some studies have focused on selective photodamage induced in bacterial and fungal cells 29, 30, 31 by near‐infrared (NIR) irradiation, to date, little is known about the effect of laser irradiation on bacterial biofilms present in infected wounds.

In this work, a possible killing or disruptive effect of NIR laser was evaluated on mono and polymicrobial biofilms, formed by two pathogenic bacteria strains both isolated from a chronic venous leg ulcer.

As antibiotic therapy resistance constitutes nowadays, more than never, a problem to overcome, alternative bacterial eradication treatments are demanded. This work represents an initial attempt to study new mechanisms that might be involved in the modification of bacterial biofilms structure.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains

Two bacterial strains, Staphylococcus aureus PECHA10 and Pseudomonas aeruginosa PECHA9, were isolated from the wound of a patient with chronic venous leg ulcer and used for the in vitro biofilm formation. Swab sample was cultured on blood agar, McConkey agar, Mannitol Salt agar and Sabouraud agar (Oxoid, Milan, Italy) for bacteria and yeast recovery. The two isolated strains were identified by VITEK® 2 Technology (Biomerieux, Florence, Italy) and stored in Microbank™ system (Biolife, Milan, Italy) at −80°C.

Biofilm growth condition

The two clinical strains used for the experiments were separately harvested in Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB; Oxoid, Milan, Italy) and incubated overnight aerobically at 37°C. In order to obtain log‐phase broth cultures, the overnight cultures were diluted 1:5 in fresh TSB supplemented with 0·5% (w/v) glucose (Sigma Aldrich, Milan, Italy) and incubated aerobically for 2 hours at 37°C under shaking (100 rpm); these cultures were then adjusted to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0·1 corresponding to approximately 108 CFU/ml; a final dilution of 1:100 in TSB supplemented with 0·5% (w/v) glucose was performed for each strain. Such standardised broth cultures were used to prepare a mixture 1:1 (v/v) of the two strains.

The above prepared cultures of S. aureus PECHA10, P. aeruginosa PECHA9 and their mixture were then inoculated into a collagen type I‐coated, flat‐bottomed 96‐well polystyrene microtiter plate (Iwaki, Tokyo, Japan) (200 µl/well) for biofilm formation assay and colony forming units (CFU) count.

Moreover, 2 ml was poured into collagen type I‐coated 35 mm of diameter polystyrene plates (Iwaki, Tokyo, Japan) for cell viability assay. The microplates and plates were incubated aerobically for 24 hours at 37°C.

Laser treatment

Twenty‐four hours preformed biofilms, grown on TSB supplemented with 0·5% (w/v) glucose, were submitted to a laser treatment with an NIR diode laser (A.R.C. Laser GmbH, Nürnberg, Germany), with a wavelength of 980 nm coupled to a 400 nm optical fibre. The NIR laser was applied with an energy level of 10 W, with a distance of 5 cm, delivering a total energy density of 148 J/cm2. These parameters were selected in accordance to the clinical experimental practice performed in the Division of Vascular Surgery of “Santo Spirito” Hospital of Pescara to treat infected chronic wounds.

After the laser treatment, the biofilms were investigated for biomass measurement, CFU count and cell viability assay in respect to the untreated corresponding controls.

All tests were carried out for two independent experiments, and each experiment was performed in triplicate.

Biofilm formation assay

The treated biofilms and respective controls were analysed for the biomass measurement. Planktonic cells were removed and biofilms were rinsed with 300 µl of phosphate buffered saline (PBS), pH 7·3, fixed by air drying and stained with 200 µl of crystal violet 0·5% (w/v) for 2 minutes. The stained biofilms were rinsed with 300 µl of PBS, air dried, eluted with 200 µl of acetic acid 33% and then the optical density was measured at 595 nm using a microplate reader (SAFAS, Munich, Germany). The results were expressed as average of OD595 values of three replicates (32).

The statistical significance of difference between controls and experimental groups was evaluated using Student's t test. Probability levels of <0·05 were considered statistically significant.

Cell viability assay

For the evaluation of cells viability, both planktonic and sessile phases of S. aureus PECHA10, P. aeruginosa PECHA9 and of their polymicrobial biofilms were stained using the Live/Dead BactLight bacterial viability kit (Invitrogen, Milan, Italy). The planktonic cells were removed from each plate, centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 10 minutes at 4°C and resuspended in 500 µl of the appropriate mixture of SYTO 9 and propidium iodide stains, followed by 20 minutes of incubation at room temperature in the dark, as indicated by the manufacturer's instructions. Five microlitres of the stained suspensions were immediately examined using a fluorescent Leica 4000 DM microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany). Instead, the sessile cells were washed with 1 ml of PBS and stained with 500 µl of the appropriate mixture of SYTO 9 and propidium iodide stains, incubated for 20 minutes at room temperature in the dark; then, were rinsed with 1 ml of PBS and examined under fluorescence. Images were recorded at an emission wavelength of 500 nm for SYTO 9 (green fluorescence) and of 635 nm for propidium iodide (red fluorescence).

Microscopic observations were carried out in triplicate. Ten fields of view randomly chosen for each slide were examined. The counts were repeated independently by three microbiologists by using an image analysis software (QWIN, Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany).

Colony forming unit count

The planktonic cells were removed from each well of microplates, vortexed, serially diluted (1:10) on TSB, plated on Tryptic Soy Agar (TSA) (Oxoid, Milan, Italy) and incubated aerobically for 24 hours at 37°C; the biofilms were rinsed with PBS; then, 100 µl of PBS was added to each well to collect cells using a cell scraper (Corning, Turin, Italy). Each sample was then vortexed, serially diluted (1:10) on TSB, plated on TSA and incubated aerobically for 24 hours at 37°C.

The concentration was calculated as mean value of five replicates for both mono and polymicrobial biofilms and reported as CFU/ml. The statistical significance of differences between controls and experimental groups was evaluated using Student's t test. Probability levels of <0·05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

In this study, the effect of NIR laser on mono and polymicrobial biofilms of S. aureus PECHA10 and P. aeruginosa PECHA9 pathogenic bacteria, isolated from a chronic venous leg ulcer, was evaluated.

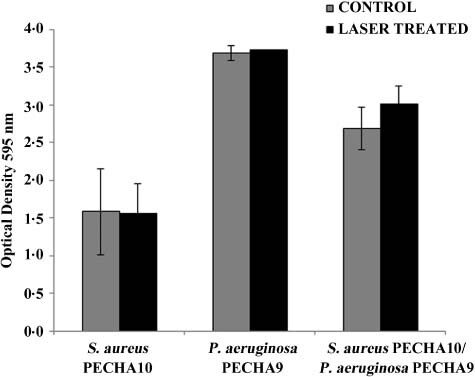

The laser effect on 24‐hour mature biofilms, grown under static conditions, showed no significant differences in terms of biomass reduction in both mono and polymicrobial biofilms when compared to the controls (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Laser effect on Staphylococcus aureus PECHA10, Pseudomonas aeruginosa PECHA9 and their mixture biofilms measured spectrophotometrically by OD595 (mean ± SD) causing no significant reduction in biofilm (P < 0·05).

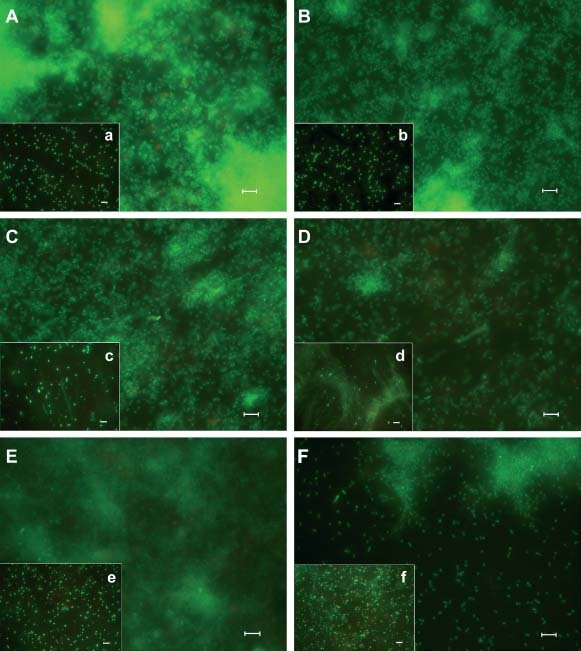

Similarly, the cell viability of S. aureus PECHA10 and P. aeruginosa PECHA9 in mono and polymicrobial biofilms was not affected by laser irradiation as shown in Figure 2 in which a large prevalence of live cells was detected. The QWIN analysis software (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) recorded a similar percentage of live cells (from 98 to 99%) in sessile and planktonic phases of both treated and untreated mono and polymicrobial biofilms. A qualitative evaluation of Live/Dead images displayed a modification on the compactness of treated biofilms in respect to the controls, in particular in P. aeruginosa biofilm and in polymicrobial biofilm as shown in Figure 2C, D and E, F, respectively. On the contrary, a reduction on bacterial growth of treated sessile and planktonic cells was observed in some cases (Table 1). In particular, the CFU count of sessile and planktonic S. aureus PECHA10 was significantly lower (P < 0·05) in treated samples than in respective controls. A similar trend was also noticed in the polymicrobial biofilm (P = 0·16 and 0·01 for sessile and planktonic phases, respectively), whereas no reduction of bacterial growth was recorded in P. aeruginosa PECHA9 biofilm (P = 0·42 and 0·09 for sessile and planktonic phases, respectively).

Figure 2.

Representative fluorescence micrographs of Staphylococcus aureus PECHA10, Pseudomonas aeruginosa PECHA9 and their mixture biofilms after 24 hours of incubation, showing the preservation of cells viability with and without laser treatment. Laser non treated samples (on the left): Biofilm (A) and planktonic cells (a) of S. aureus PECHA10; biofilm (C) and planktonic cells (c) of P. aeruginosa PECHA9 and biofilm (E) and planktonic cells (e) of mixed species. Laser treated samples (on the right): Biofilm (B) and planktonic cells (b) of S. aureus PECHA10; biofilm (D) and planktonic cells (d) of P. aeruginosa PECHA9 and biofilm (F) and planktonic cells (f) of mixed species. Scale bars = 5 µm.

Table 1.

Colony forming unit count (CFU/ml) of Staphylococcus aureus PECHA10, Pseudomonas aeruginosa PECHA9 and their mixture detected in the sessile and planktonic phases

| Species | Control | Laser treated | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sessile | Planktonic | Sessile | Planktonic | |

| S. aureus PECHA10 | 2·1 × 109 | 1·2 × 108 | 1·2 × 108 | 6.0 × 107 |

| P. aeruginosa PECHA9 | 5·2 × 109 | 1·2 × 1010 | 6·6 × 109 | 3·3 × 109 |

| S. aureus PECHA10/P. aeruginosa PECHA9 | 1.0 × 1010 | 2·2 × 1010 | 3·2 × 109 | 3·1 × 109 |

DISCUSSION

Presence of infection within the wound bed can greatly contribute to a state of chronicity and also delay the wound‐healing process (4). Currently, wound debridement, along with dressings containing antimicrobial agents and systemic antimicrobial therapy represent the main available means used by clinicians in the wound infection handling; however, these treatment strategies usually appear to be ineffective in the infection eradication (7).

Many studies 4, 15 have pointed out biofilms as a major factor for the chronic behaviour of wounds. Therefore, the presence, within a wound, of microorganisms capable to form biofilms is definitely an important contributing factor to the difficulty of eradication. The isolates used in our assays, P. aeruginosa and S. aureus, both showed to be good biofilm producers, contributed to the chronicity state of the patient's leg ulcer. Moreover, the occurrence of polymicrobial biofilms may be an additional problem, hampering even more the eradication and therefore the healing (21). Thus, to verify the laser effect, we performed not only monomicrobial biofilms, but also polymicrobial ones.

The laser treatment applied to 24 hour mature monomicrobial and polymicrobial biofilms did not affect the biofilm cells viability and biomass, although a small reduction on the compactness of those biofilms was recorded at microscopic observation. These results can be explained by the NIR laser inability to pass through the exopolymeric substances of mono and polymicrobial biofilms, and thus non affecting cell viability. In any case, the modifications recorded in the compactness of treated biofilms in respect to the corresponding non treated controls might be associated to a mild disruptive effect of NIR laser on the top of the biofilm. At this point, it will be interesting to use antimicrobial agents after the laser treatment, which could facilitate their access to the bacterial target.

In accordance to our results, non effective killing action in methicillin‐resistant S. aureus biofilm was shown by Krespi et al. (33) by using NIR laser alone; however, this effect was achieved when a pretreatment with a shock wave laser was performed.

A reduction on CFU count was significant only in some cases analysed as in both treated phases of S. aureus PECHA10 and in treated planktonic phase of polymicrobial biofilm in respect to controls. This result can be interpreted by the presence of a viable but non culturable cell subpopulation – a reversible, quiescent state typically associated to biofilms of numerous bacteria, which exhibit a loss of culturability. In this ‘dormant state’, bacteria are characterised by the presence of viable cells, observed as green fluorescence at microscope examination, unable to replicate and therefore unable to be cultivated 34, 35.

Although the laser benefits are mostly due to its ability to promote regeneration of damaged cells, laser irradiation may modify the metabolic features in the microbial cells and therefore might constitute a stressful condition inducing a small part of the biofilm population to enter a ‘persister’ cell state (36). This particular state could lead to a restraint in bacterial cell proliferation, which may contribute to a minor recruitment of immune cells in the bed wound. Therefore, wound healing could be favoured through a slowdown in the inflammatory process together with the tissue regeneration effect of laser.

Our in vitro experimental model was performed using collagen type I‐coated plates in order to better resemble the in vivo bacterial growth conditions. Similarly, Werthén et al. (37) have also developed a new in vitro model to investigate bacterial biofilms in chronic wounds, with bacteria growing as biofilm aggregates in a collagen gel matrix.

Although, our results do not point out a considerable effect of NIR laser on S. aureus, P. aeruginosa and their polymicrobial biofilms, they may highlight the need of performing new combined strategies to improve the healing of infected wounds instead of using pharmacological or laser therapies alone. Further work should consist in performing assays that can better mimic the wound bed and that also combine the use of different types of laser together with antimicrobial therapy.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by a grant awarded by Ministero Istruzione, Università e Ricerca, Italy.

The authors thank Soraya Di Bartolomeo, Emanuela Di Campli and Alessandra Felici for their technical support.

Marina Baffoni and Lucinda J. Bessa contributed equally to this work.

REFERENCES

- 1. Fazli M, Bjarnsholt T, Kirketerp‐Møller K, Jørgensen B, Andersen AS, Krogfelt KA, Givskov M, Tolker‐Nielsen T. Nonrandom distribution of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus in chronic wounds. J Clin Microbiol 2009;47:4084–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kirketerp‐Møller K, Jensen PØ, Fazli M, Madsen KG, Pedersen J, Moser C, Tolker‐Nielsen T, Høiby N, Givskov M, Bjarnsholt T. Distribution, organization, and ecology of bacteria in chronic wounds. J Clin Microbiol 2008;46:2717–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Siddiqui AR, Bernstein JM. Chronic wound infection: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol 2010;28:519–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bjarnsholt T, Kirketerp‐Møller K, Jensen PØ, Madsen KG, Phipps R, Krogfelt K, Høiby N, Givskov M. Why chronic wounds will not heal: a novel hypothesis. Wound Repair Regen 2008;16:2–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Martin JM, Zenilman JM, Lazarus GS. Molecular microbiology: new dimensions for cutaneous biology and wound healing. J Invest Dermatol 2010;130:38–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Madsen SM, Westh H, Danielsen L, Rosdahl VT. Bacterial colonization and healing of venous leg ulcers. APMIS 1996;104:895–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Howell‐Jones RS, Wilson MJ, Hill KE, Howard AJ, Price PE, Thomas DW. A review of the microbiology, antibiotic usage and resistance in chronic skin wounds. J Antimicrob Chemother 2005;55:143–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Robson MC. Wound infection. A failure of wound healing caused by an imbalance of bacteria. Surg Clin North Am 1997;77:637–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bowler PG, Davies BJ. The microbiology of infected and noninfected leg ulcers. Int J Dermatol 1999;38:573–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brook I, Frazier EH. Aerobic and anaerobic microbiology of chronic venous ulcers. Int J Dermatol 1998;37:426–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Davies CE, Hill KE, Newcombe RG, Stephens P, Wilson MJ, Harding KG, Thomas DW. A prospective study of the microbiology of chronic venous leg ulcers to reevaluate the clinical predictive value of tissue biopsies and swabs. Wound Repair Regen 2007;15:17–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cooper RA, Ameen H, Price P, McCulloch DA, Harding KG. A clinical investigation into the microbiological status of ‘locally infected’ leg ulcers. Int Wound J 2009;6:453–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gjødsbøl K, Christensen JJ, Karlsmark T, Jørgensen B, Klein BM, Krogfelt KA. Multiple bacterial species reside in chronic wounds: a longitudinal study. Int Wound J 2006;3:225–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Davies CE, Wilson MJ, Hill KE, Stephens P, Hill CM, Harding KG, Thomas DW. Use of molecular techniques to study microbial diversity in the skin: chronic wounds reevaluated. Wound Repair Regen 2001;9:332–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Thomsen TR, Aasholm MS, Rudkjøbing VB, Saunders AM, Bjarnsholt T, Givskov M, Kirketerp‐Møller K, Nielsen PH. The bacteriology of chronic venous leg ulcer examined by culture‐independent molecular methods. Wound Repair Regen 2010;8:38–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dowd SE, Wolcott RD, Sun Y, McKeehan T, Smith E, Rhoads D. Polymicrobial nature of chronic diabetic foot ulcer biofilm infections determined using bacterial tag encoded FLX amplicon pyrosequencing (bTEFAP). PLoS One 2008;3:e3326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Harmsen M, Yang L, Pamp SJ, Tolker‐Nielsen T. An update on Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation, tolerance, and dispersal. FEMS Immunol Microbiol 2010;59:253–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Otto M. Staphylococcal biofilms. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2008;322:207–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Malic S, Hill KE, Hayes A, Percival SL, Thomas DW, Williams DW. Detection and identification of specific bacteria in wound biofilms using peptide nucleic acid fluorescent in situ hybridization (PNA FISH). Microbiology 2009;155:2603–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Davis SC, Ricotti C, Cazzaniga A, Welsh E, Eaglstein WH, Mertz PM. Microscopic and physiologic evidence for biofilm‐associated wound colonization in vivo. Wound Repair Regen 2008;16:23–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. James GA, Swogger E, Wolcott R, Pulcini E, Secor P, Sestrich J, Costerton JW, Stewart PS. Biofilms in chronic wounds. Wound Repair Regen 2008;16:37–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Burmølle M, Thomsen TR, Fazli M, Dige I, Christensen L, Homøe P, Tvede M, Nyvad B, Tolker‐Nielsen T, Givskov M, Moser C, Kirketerp‐Møller K, Johansen HK, Høiby N, Jensen PØ, Sørensen SJ, Bjarnsholt T. Biofilms in chronic infections – a matter of opportunity – monospecies biofilms in multispecies infections. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 2010;59:324–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Costerton W, Veeh R, Shirtliff M, Pasmore M, Post C, Ehrlich G. The application of biofilm science to the study and control of chronic bacterial infections. J Clin Invest 2003;112:1466–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Percival SL, Thomas JG, Williams DW. Biofilms and bacterial imbalances in chronic wounds: anti‐Koch. Int Wound J 2010;7:169–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gurjala AN, Geringer MR, Seth AK, Hong SJ, Smeltzer MS, Galiano RD, Leung KP, Mustoe TA. Development of a novel, highly quantitative in vivo model for the study of biofilm‐impaired cutaneous wound healing. Wound Repair Regen 2011;19:400–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hawkins D, Houreld N, Abrahamse H, Ann NY. Low level laser therapy (LLLT) as an effective therapeutic modality for delayed wound healing. Acad Sci 2005;1056:486–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rodrigo SM, Cunha A, Pozza DH, Blaya DS, Moraes JF, Weber JB, de Oliveira MG. Analysis of the systemic effect of red and infrared laser therapy on wound repair. Photomed Laser Surg 2009;27:929–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Posten W, Wrone DA, Dover JS, Arndt KA, Silapunt S, Alam M. Low‐level laser therapy for wound healing: mechanism and efficacy. Dermatol Surg 2005;31:334–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bornstein E, Hermans W, Gridley S, Manni J. Near‐infrared photoinactivation of bacteria and fungi at physiologic temperatures. Photochem Photobiol 2009;85:1364–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Guffey JS, Wilborn J. Effects of combined 405‐nm and 880‐nm light on Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa in vitro. Photomed Laser Surg 2006;24:680–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hawkins‐Evans DH, Abrahamse H. Efficacy of three different laser wavelengths for in vitro wound healing. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed 2008;24:199–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Grande R, Di Giulio M, Bessa LJ, Di Campli E, Baffoni M, Guarnieri S, Cellini L. Extracellular DNA in Helicobacter pylori biofilm: a backstairs rumour. J Appl Microbiol 2011;11:490–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Krespi YP, Kizhner V, Nistico L, Hall‐Stoodley L, Stoodley P. Laser disruption and killing of methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. Am J Otolaryngol 2011;32:198–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cellini L, Robuffo I, Di Campli E, Di Bartolomeo S, Taraborelli T, Dainelli B. Recovery of Helicobacter pylori ATCC43504 from a viable but not culturable state: regrowth or resuscitation? APMIS 1998;106:571–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Oliver JD. The viable but nonculturable state in bacteria. J Microbiol. 2005;43:93–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Percival SL, Hill KE, Malic S, Thomas DW, Williams DW. Antimicrobial tolerance and the significance of persister cells in recalcitrant chronic wound biofilms. Wound Repair Regen 2011;19:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Werthén M, Henriksson L, Jensen PØ, Sternberg C, Givskov M, Bjarnsholt T. An in vitro model of bacterial infections in wounds and other soft tissues. APMIS 2010;118:156–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]