Abstract

In diabetic patients, there is impairment in angiogenesis, neovascularisation and failure in matrix metalloproteineases (MMPs), keratinocyte and fibroblast functions, which affects wound healing mechanism. Hence, diabetic patients are more prone to infections and ulcers, which finally result in gangrene. Ferulic acid (FA) is a natural antioxidant found in fruits and vegetables, such as tomatoes, rice bran and sweet corn. In this study, wound healing activity of FA was evaluated in streptozotocin‐induced diabetic rats using excision wound model. FA‐treated wounds were found to epithelise faster as compared with diabetic wound control group. The hydroxyproline and hexosamine content increased significantly when compared with diabetic wound control. FA effectively inhibited the lipid peroxidation and elevated the catalase, superoxide dismutase, glutathione and nitric oxide levels along with the increase in the serum zinc and copper levels probably aiding the wound healing process. Hence, the results indicate that FA significantly promotes wound healing in diabetic rats.

Keywords: Diabetic wound healing, Excision wound model, Ferulic acid, Hexosamine, Hydroxyproline

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is the major metabolic disorder causing serious global health problems. In 2011, 366 million people were diabetic and this number is expected to rise to 552 million by 2030. Most people with diabetes live in low‐ and middle‐income countries including India, and these countries will observe the greatest increase over the next 19 years 1. World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that India and China share major diabetic population with more than 120 million diabetic patients and thus are most endangered countries in the world. In 2005, an estimated 1·1 million people died because of diabetes and its complications, and WHO predicted that diabetes‐related deaths will increase by more than 50% in the next 10 years 2. This major increase in morbidity and mortality of diabetes is because of the development of various macro‐ and micro‐vascular complications.

In diabetic patients, there is impairment in angiogenesis, neovascularisation and failure in matrix metalloproteineases (MMPs), keratinocyte and fibroblast functions, which affects wound healing mechanism. Hence, diabetic patients are more prone to infections and ulcers, which finally result in gangrene 3.

Hyperglycaemia is the major cause that affects macrophage cytokine release in the wound environment 4. Hyperglycaemia leads to decreased host immunity, impaired angiogenesis and neovascularisation 5, 6, increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and advanced glycation end products (AGEs) ultimately resulting in delayed wound healing 7. Other factors apart from diabetes that delay wound healing includes infection, poor blood supply, exposure to ionising radiation, age, temperature, nutrition, systemic infection, administration of glucocorticoids and genetic defect (Danlos syndrome) 8.

Ferulic acid (FA; 4‐hydroxy‐3‐methoxycinnamic acid) is a phenolic compound and a natural antioxidant found in many staple foods, such as fruits, vegetables, cereals, coffee and in plant constituent exhibiting a wide range of therapeutic effects such as anticancer 9, antidiabetic 10, radioprotective 11, neuroprotective 12 and anti‐inflammatory activity 13. FA serves as an angiogenic agent to augment angiogenesis both in vitro and in vivo through the modulation of VEGF, PDGF and HIF‐1α 14. It also promotes endothelial cell proliferation through the modulation of cyclin D1 and VEGF 15. FA significantly decreases blood glucose level and increases plasma insulin level by elevating glucokinase activity and production of glycogen in the liver 10. FA has an anti‐inflammatory activity as it can decrease the levels of inflammatory responses mediated by PGE2, TNF‐α and iNOS expression 16, 17. FA also has antimicrobial and antibacterial activity 18. Considering the various reported pharmacological activities, it was proposed that FA may prove to be useful in the treatment of diabetic wound healing and hence this study was undertaken to evaluate the effect of FA on diabetic wound healing.

Materials and methods

Experimental animals

All procedures in the study were approved by the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee (SCOP/IAEC/Approval/2011‐ 12/10), constituted for the purpose of control and supervision of experimental animals by Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government of India, New Delhi, India. Wistar rats of either sex weighing between 170 and 200 g were obtained from National Institute of Biosciences, Pune. Animals were housed into groups of six in polypropylene cages containing husk as bedding material and maintained under controlled conditions of temperature (23 ± 2°C), humidity (55 ± 5%) and 12‐h light and 12‐h dark cycle in the animal house of Sinhgad College of Pharmacy, Pune, India. The animals were fed with standard pellet diet (Amrut feed, Pune, India) and water ad libitum.

Drugs and chemicals

Streptozotocin (STZ) (Enzo Life Science, Exeter, UK), vaseline ointment (Analab Fine Chemicals, Mumbai, India), mupirocin ointment (GSK, Nasik, India), FA (Otto Chemika, India), hydroxyproline (Sigma Chemicals, St. Louis, MO), glucosamine HCl (Otto Chemika, Mumbai, India), chloramine‐T (SD Finechem, Mumbai, India), acetyl acetone (Loba Chemie, Mumbai, India) and other diagnostic kits (Biolab diagnostics, Mumbai, India) were used in this study. Fresh drug solutions were prepared for daily work and stored in air‐tight, amber‐coloured bottle at room temperature until use.

Dosage of drugs

The dose of FA was selected based on previous study by Balasubashini et al. 19, where 10 mg/kg orally was effective in the treatment of diabetic nephropathy. Hence, FA was administered in distilled water at a dose of 10 and 20 mg/kg, orally and made in the form of a vaseline ointment (2%) for topical delivery. STZ was freshly prepared in cold citrate buffer (pH 4·5) and administered at a dose of 50 mg/kg, i.p.

Blood sampling

Blood sample was withdrawn by puncturing tail vein or retro‐orbital plexus for glucose and other biochemical estimations.

Induction of diabetes

All the rats were fasted overnight before administration of STZ. STZ was administered at a dose of 50 mg/kg, i.p. using a freshly prepared 0·1 M cold citrate buffer (pH 4·5). After 2 days of STZ injection, blood glucose level was estimated using glucometer. Rats with blood glucose levels more than 250 mg/dl were considered as diabetic and used for further study 19. The percentage change in the body weight was calculated at the end of the study.

Excision wound model

Animals were divided into following seven groups (n = 6). The animals in groups I and II were non‐diabetic, and in groups III to VII were diabetic. Group I (NWC): animals received distilled water (5 ml/kg, orally) and served as normal wound control (NWC), group II (VWC): animals were applied vaseline ointment (2%, topically) and served as vaseline wound control (VWC), group III (DWC): animals were administered distilled water (5 ml/kg, orally) and served as diabetic wound control (DWC), group IV (FA 10): animals were administered FA (10 mg/kg, orally), group V (FA 20): animals were administered FA (20 mg/kg, orally), group VI (FA 2%): animals were applied FA ointment (2%, topically), and group VII (Mupirocin 2%): animals were applied mupirocin ointment (2%, topically).

All the rats were anaesthetised with anaesthetic ether and shaved on both sides of the back with a blade and the area of the wound to be created was outlined on the back of the animals with methylene blue using a circular stainless steel stencil. The full thickness of 2·5 cm length and 0·2 cm depth of the excision wound was created along the markings using toothed forceps, surgical blade and pointed scissors. Animals were closely observed for any infection and those which showed signs of infection were replaced. The day of the wound creation is considered as day 0. On the 4th, 8th and 14th post‐wound treated day, the granulation tissue that was formed on the wounds was excised and stored in deep freezer (−80°C) for protein estimation. Wound area and percentage wound closure were measured on days 0, 5, 8, 11 and 14 for all the groups using AWAMS software (Advanced Wound Area Measurement System) 20, 21.

|

where n = numbers of days (0, 5, 8, 11 and 14th).

Estimation of hydroxyproline and hexosamine

On 4th, 8th and 14th days of the post‐surgery of excision, a piece of granulation tissue from the healed wound area was collected and analysed for hydroxyproline content, which is the predominant index of collagen turnover. Tissues were dried in a hot air oven at 60–70°C to constant weight and were hydrolysed in 6 N HCl at 130°C for 4 h in a sealed tube. The hydrolysate was neutralised to pH 7·0 and was subjected to chloramine‐T oxidation for 20 min, the reaction was terminated by addition of 0·4 M perchloric acid and colour was developed with the help of Ehrlich reagent at 60°C and measured at 557 nm using UV–Vis spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Columbia, MD) 22.

For estimation of hexosamine, the weighed granulation tissues were hydrolysed in 6 N HCl for 8 h at 98°C, neutralised to pH 7 with 4 N NaOH and diluted with distilled water. The diluted solution was mixed with acetyl acetone solution and heated to 96°C for 40 min. The mixture was cooled and 96% ethanol was added, followed by p‐dimethylamino‐benzaldehyde solution (Ehrlich's reagent). The solution was thoroughly mixed, kept at room temperature for 1 h and the absorbance was measured at 530 nm using a double beam UV–Vis spectrophotometer (Shimadzu). The amount of hexosamine was determined by comparing with a standard curve. Hexosamine content was expressed as milligram per gram dry tissue weight 23.

Estimation of trace elements (zinc and copper)

A stock solution (1000 ppm) of zinc and copper was prepared using inductively coupled spectroscopy (ICP) multi‐element standard solution IV in deionised water. Working standards for zinc and copper were prepared in the range of 5, 10 and 15 ppm from stock solution in deionised water using ICP multi‐element standard solution IV, which contains Thallium (I) nitrate and nitric acid (MERCK, Darmstadt, Germany). The serum Zn and Cu was analysed by Spectra AA 220 atomic absorption spectrometer with a deuterium background correction. The measurements were done for each sample using flame atomisation technique with light at 213·9 wavelength with atomisation in the air/acetylene flame. Serum trace element levels were expressed in micrograms per decilitre 24.

Estimation of antioxidant activity

To evaluate antioxidant activity, the blood was collected on 0 and 14 days by retro‐orbital plexus and subjected to centrifugation at 506.11 g for 10 min (Micro centrifuge) in order to separate plasma. The serum was used for the antioxidative enzyme assay. The extent of lipid peroxidation (LPO) was determined by analysing the levels of thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) by method of Uchiyama and Mihara. Endogenous antioxidant status was evaluated by estimating the levels of reduced glutathione (GSH) by the method of Sedlak and Lindsay and activities of superoxide dismutase (SOD) by Kono. Catalase (CAT) was assayed by the standard method of Aebi 25, 26, 27, 28.

Estimation of nitric oxide

The stable end products of nitric oxide (NO) biosynthesis were measured by estimating nitrite levels in the serum. Greiss reagent (500 µl; 1:1 solution of 1% sulphanilamide in 5% phosphoric acid and 0·1% napthaylamine diamine dihydrochloric acid in water) was added to 100 µl of serum and absorbance was measured at 546 nm using double beam UV‐visible spectrophotometer. 29. Nitrite concentration was calculated using a standard curve for sodium nitrite and expressed as nanogram per milligram of protein.

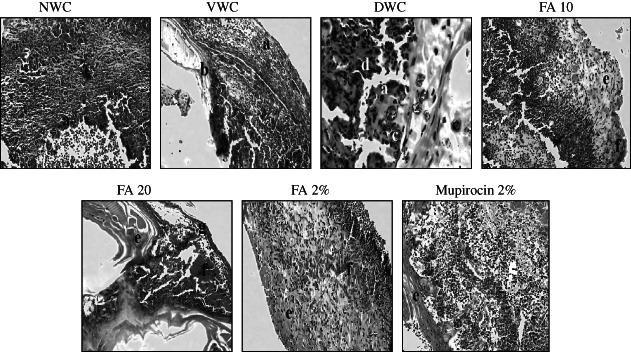

Histological study

Granulation tissue was fixed in 10% solution of neutral formalin, embedded in paraffin and cut into semi‐thin sections. The sections were stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and examined under light microscopy (100×).

Statistical analysis

Values are expressed as mean ± SEM. Results were analysed using two‐way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni test. The values were considered to be statistically significant at P < 0·05.

Results

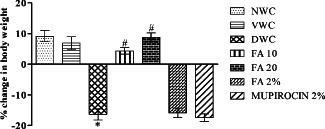

Percentage change in body weight

There was significant decrease in body weight in diabetic wound control when compared with normal wound control (P < 0·001). Treatment with FA 10 and FA 20 for 14 days significantly increased the body weight when compared with diabetic wound control (P < 0·001) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Effect of ferulic acid on percentage change in body weight in streptozotocin (STZ)‐induced diabetic rats. Group I (NWC): normal wound control, group II: vaseline wound control (VWC), group III: diabetic wound control (DWC), group IV: ferulic acid 10 mg/kg orally (FA 10), group V: ferulic acid 20 mg/kg orally (FA 20), group VI: ferulic acid ointment topically (FA 2%), group VII: mupirocin ointment topically (Mupirocin 2%). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM for six rats in each group. * P < 0.001 as compared to NWC group and # P < 0.001 compared to DWC group on respective days. Statistical analysis was done by using one‐way ANOVA followed by Tukey test.

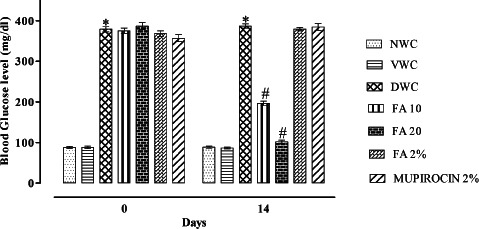

Blood glucose level

There was significant increase in blood glucose level in diabetic wound control when compared with normal wound control (P < 0·001). Administration of FA 10 and FA 20 for 14 days significantly decreased the blood glucose level as compared to diabetic wound control (P < 0·001) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Effect of ferulic acid on blood glucose level in streptozotocin (STZ)‐induced diabetic rats. Group I (NWC): normal wound control, group II: vaseline wound control (VWC), group III: diabetic wound control (DWC), group IV: ferulic acid 10 mg/kg orally (FA 10), group V: ferulic acid 20 mg/kg orally (FA 20), group VI: ferulic acid ointment topically (FA 2%), group VII: mupirocin ointment topically (Mupirocin 2%). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM for six rats in each group. * P < 0.001 as compared to NWC group and # P < 0.001 as compared to DWC group on respective days. Statistical analysis was done by using two way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni test.

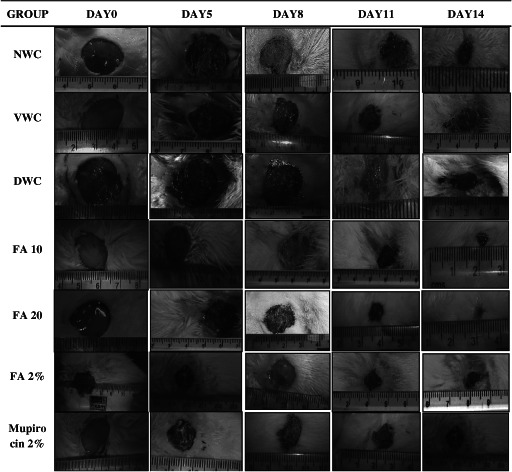

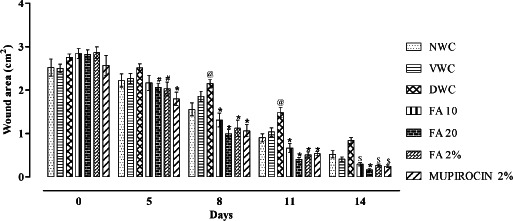

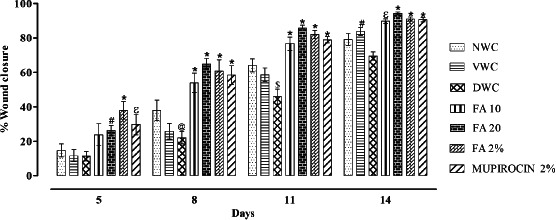

Wound area and % wound closure assessment

Quantitative measurements of wound size are routinely used to assess initial wound size before and after debridement, as well as progress towards wound closure. Photographs of the wound and wound area measurement were performed at the wound creation day, that is, 0 and on days 5, 8, 11 and 14 (Figure 3). There was significant increase in wound area in diabetic wound control when compared with normal wound control (P < 0·001). However, orally and topically treated FA showed significant decrease in wound area when compared with diabetic wound control (P < 0·001) (Figure 4). Further, there was significant decrease in % wound closure in diabetic wound control when compared with normal wound control (P < 0·001). Orally and topically FA treated groups showed significant increase in % wound closure when compared with diabetic wound control (P < 0·001) (Figure 5).

Figure 3.

Photographs of excision wound on days 0, 5, 8, 11 and 14. Group I (NWC): normal wound control, group II (VWC): vaseline wound control, group III: diabetic wound control (DWC), group IV (FA 10): ferulic acid 10 mg/kg orally, group V (FA 20): ferulic acid 20 mg/kg orally, group VI (FA 2%): ferulic acid ointment topically, group VII (Mupirocin 2%): mupirocin ointment topically.

Figure 4.

Effect of ferulic acid on wound area in streptozotocin (STZ)‐induced diabetic rats. Group I (NWC): normal wound control, group II: vaseline wound control (VWC), group III: diabetic wound control (DWC), group IV: ferulic acid 10 mg/kg orally (FA 10), group V: ferulic acid 20 mg/kg orally (FA 20), group VI: ferulic acid ointment topically (FA 2%), group VII: mupirocin ointment topically (Mupirocin 2%). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM for six rats in each group. @ P < 0.01 as compared to NWC group and # P < 0.05, $ P < 0.01, * P < 0.001 compared to DWC group on respective days. Statistical analysis was done by using two way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni test.

Figure 5.

Effect of ferulic acid on % wound closure in streptozotocin (STZ)‐induced diabetic rats. Group I (NWC): normal wound control, group II: vaseline wound control (VWC), group III: diabetic wound control (DWC), group IV: ferulic acid 10 mg/kg orally (FA 10), group V: ferulic acid 20 mg/kg orally (FA 20), group VI: ferulic acid ointment topically (FA 2%), group VII: mupirocin ointment topically (Mupirocin 2%). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM for six rats in each group. @ P < 0.05, $ P < 0.01 as compared to NWC group and # P < 0.05, ɛ P < 0.01, * P < 0.001 compared to DWC group on respective days. Statistical analysis was done by using two way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni test.

Determination of hydroxyproline and hexosamine content

The hydroxyproline and hexosamine content of granulation tissue of 4, 8 and 14 post‐surgery days are shown in Table 1. There was a significant decrease in hydroxyproline and hexosamine content in diabetic wound control as compared to normal wound control (P < 0·001). However, orally as well as topically treated FA groups showed significantly increased hydroxyproline and hexosamine content when compared to diabetic wound control (P < 0·001).

Table 1.

Effect of ferulic acid on hydroxyproline and hexosamine content in granulation tissue in STZ‐induced diabetic rats. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM for six rats in each group

| Group no. | Group | Hydroxyproline content (mg/g tissue) | Hexosamine content (mg/100 mg tissue) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 4 | Day 8 | Day 14 | Day 4 | Day 8 | Day 14 | ||

| I | NWC | 15·29 ± 1·21 | 12·97 ± 0·60 | 13·06 ± 0·76 | 0·776 ± 0·043 | 0·735 ± 0·036 | 0·731 ± 0·041 |

| II | VWC | 16·30 ± 1·87 | 13·66 ± 1·38 | 13·50 ± 1·27 | 0·715 ± 0·045 | 0·691 ± 0·047 | 0·710 ± 0·043 |

| III | DWC | 4·64 ± 0·40* | 3·64 ± 0·53* | 3·02 ± 0·39* | 0·285 ± 0·012* | 0·235 ± 0·016* | 0·193 ± 0·020* |

| IV | FA 10 | 8·40 ± 0·52** | 10·18 ± 0·36*** | 8·66 ± 0·46*** | 0·366 ± 0·024** | 0·410 ± 0·023*** | 0·398 ± 0·031*** |

| V | FA 20 | 9·69 ± 1·03*** | 12·57 ± 1·06*** | 10·70 ± 0·52*** | 0·436 ± 0·045** | 0·511 ± 0·038*** | 0·435 ± 0·024*** |

| VI | FA 2% | 8·72 ± 0·78** | 10·07 ± 0·56*** | 9·75 ± 0·67*** | 0·393 ± 0·020 | 0·425 ± 0·025*** | 0·393 ± 0·020*** |

| VII | Mupirocin 2% | 9·71 ± 0·77*** | 10·88 ± 0·58*** | 10·18 ± 0·63*** | 0·386 ± 0·037 | 0·431 ± 0·038*** | 0·386 ± 0·037*** |

STZ, streptozotocin; NWC, normal wound control; VWC, vaseline wound control; DWC, diabetic wound control.

P < 0·001 as compared to NWC group and

P < 0·01,

P < 0·001 compared to DWC group on respective days. Statistical analysis was done by using two way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni test.

Trace element levels

There was significant decrease in Zn and Cu levels in diabetic wound control when compared with normal wound control (P < 0·001). Administration of FA for 14 days significantly increased the Zn and Cu levels when compared with diabetic wound control (P < 0·001) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Effect of ferulic acid on serum trace element levels in STZ‐induced diabetic rats. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM for six rats in each group

| Group no. | Group | Serum zinc level (µg/dl) | Serum copper level (µg/dl) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 0 | Day 14 | Day 0 | Day 14 | ||

| I | NWC | 97·83 ± 3·79 | 85·50 ± 3·897 | 101·3 ± 7·182 | 95·66 ± 5·799 |

| II | VWC | 96·10 ± 4·041 | 81·07 ± 3·051 | 91·67 ± 9·084 | 83·50 ± 7·538 |

| III | DWC | 35·83 ± 2·04* | 24·66 ± 2·774* | 27·51 ± 2·817* | 16·33 ± 4·006* |

| IV | FA 10 | 29·17 ± 1·956 | 50·66 ± 3·49** | 24·83 ± 3·092 | 43·16 ± 3·59** |

| V | FA 20 | 31·42 ± 2·696 | 64·45 ± 3·807** | 31·67 ± 3·221 | 54·66 ± 6·148** |

| VI | FA 2% | 33·50 ± 2·986 | 22·57 ± 4·318 | 30·33 ± 3·694 | 24·33 ± 3·343 |

| VII | Mupirocin 2% | 32·07 ± 2·405 | 20·30 ± 2·974 | 26·50 ± 3·041 | 17·83 ± 5·406 |

STZ, streptozotocin; NWC, normal wound control; VWC, vaseline wound control; DWC, diabetic wound control.

P < 0·001 as compared to NWC group and

P < 0·001 compared to DWC group on respective days. Statistical analysis was done by using two way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni test.

Determination of antioxidant parameters

There was significant increase in malondialdehyde (MDA) level in diabetic wound control when compared with normal wound control. Further, SOD, GSH and CAT levels were significantly decreased in diabetic wound control as compared to normal wound control (P < 0·001). Whereas administration of FA for 14 days significantly increased the SOD, GSH and CAT levels, decreased MDA levels when compared with diabetic wound control (P < 0·001) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Effect of ferulic acid on oxidative stress parameters in STZ‐induced diabetic rats. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM for six rats in each group

| Group no. | Group | MDA (nmol/mg of protein) | SOD (µg/mg of protein) | GSH (ng/mg of protien) | Catalase (µg/mg of protien) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 0 | Day 14 | Day 0 | Day 14 | Day 0 | Day 14 | Day 0 | Day 14 | ||

| I | NWC | 4·33 ± 0·59 | 4·07 ± 0·47 | 73·35 ± 2·72 | 73·59 ± 2·46 | 18·97 ± 1·62 | 18·24 ± 2·22 | 40·41 ± 4·23 | 39·85 ± 3·09 |

| II | VWC | 4·43 ± 0·38 | 3·80 ± 0·17 | 70·86 ± 3·62 | 71·70 ± 3·50 | 19·33 ± 1·84 | 19·55 ± 1·57 | 38·30 ± 3·59 | 36·96 ± 3·80 |

| III | DWC | 9·03 ± 0·48* | 13·14 ± 1·01* | 48·29 ± 4·85* | 38·07 ± 3·55* | 12·31 ± 1·04* | 7·52 ± 0·81* | 17·85 ± 2·38* | 11·55 ± 1·57* |

| IV | FA 10 | 9·01 ± 0·51 | 8·65 ± 0·41*** | 47·30 ± 3·34 | 55·21 ± 5·17** | 14·05 ± 1·24 | 15·09 ± 1·42*** | 17·23 ± 1·36 | 27·63 ± 2·06*** |

| V | FA 20 | 8·92 ± 0·55 | 5·51 ± 0·44*** | 48·52 ± 4·17 | 72·82 ± 2·03*** | 12·12 ± 0·99 | 19·95 ± 1·41*** | 18·19 ± 1·67 | 33·92 ± 3·99*** |

| VI | FA 2% | 8·26 ± 0·56 | 14·45 ± 1·02 | 43·76 ± 2·54 | 36·73 ± 2·09 | 12·08 ± 0·92 | 7·90 ± 0·65 | 18·21 ± 2·58 | 13·29 ± 2·31 |

| VII | Mupirocin 2% | 9·58 ± 0·31 | 14·13 ± 1·49 | 44·77 ± 3·33 | 30·43 ± 1·87 | 12·18 ± 1·16 | 8·03 ± 0·73 | 18·83 ± 1·61 | 12·05 ± 1·58 |

GSH, glutathione; MDA, malondialdehyde; STZ, streptozotocin; SOD, superoxide dismutase; NWC, normal wound control; VWC, vaseline wound control; DWC, diabetic wound control.

P < 0·001 as compared to NWC group and

P < 0·01,

P < 0·001 compared to DWC group on respective days. Statistical analysis was done using two‐way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni test.

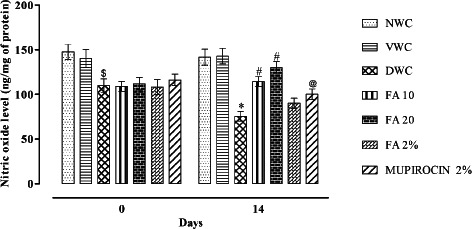

Nitric oxide

There was a significant decrease in nitric oxide level in diabetic wound control when compared with normal wound control (P < 0·001). Administration of FA for 14 days significantly increased the nitric oxide level when compared to diabetic wound control (P < 0·001) (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Effect of ferulic acid on NO level in streptozotocin (STZ)‐induced diabetic rats. Group I (NWC): normal wound control, group II: vaseline wound control (VWC), group III: diabetic wound control (DWC), group IV: ferulic acid 10 mg/kg orally (FA 10), group V: ferulic acid 20 mg/kg orally (FA 20), group VI: ferulic acid ointment topically (FA 2%), group VII: mupirocin ointment topically (Mupirocin 2%). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM for six rats in each group. $ P < 0.01, * P < 0.001 as compared to NWC group and # P < 0.001, @ P < 0.05 compared to DWC group on respective days. Statistical analysis was done by using two way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni test.

Discussion

Among diabetic complications, impaired wound healing and ulcers is one of the most common causes of gangrene and amputation in diabetic patients 30. It has substantial impact on health costs, patient health and quality of life in diabetic patients. A large number of flavonoids have got attention as effective treatment of diseases such as diabetes 31.

In this study, the effect of FA (oral and topical) in diabetic wound healing was studied in STZ‐induced diabetic rats using excision wound rat model. This is the first report to show that FA accelerates the wound healing process in diabetic animals. Experimental diabetic rats exhibited decreased collagen, reduced trace elements (Zn and Cu levels), increased serum levels of oxidative markers such as MDA while reduced level of NO. Further, depletion of endogenous antioxidants such as GSH, SOD and CAT was observed in diabetic rats affecting wound repair process reflected as impaired wound healing in diabetic control rats. FA treatment resulted in inhibition of LPO, greater collagen deposition, NO synthesis and improved endogenous antioxidants such as GSH, SOD and CAT which reflected as reduced wound areas and hence improved wound healing.

Wound healing is a complex but orderly phenomenon involving continuous cell–cell and cell–matrix interactions with three overlapping phases namely inflammation, cellular proliferation and remodelling 32, 33, 34. Tissue destruction causes acute inflammatory response, in which neutrophils, monocytes and mast cells infiltrate to the site of injury and produces cytokines 35. The released cytokines then stimulate the proliferation and migration of keratinocytes, endothelial cells and fibroblasts to the wound site. In the last step, extracellular matrix remodelling, angiogenesis and re‐epithelialisation are responsible for wound closure and scar formation. In diabetic patients, impaired wound healing results from deviation in inflammatory response 36, poor circulation 37, decreased angiogenesis 5 and insufficient fibroblast migration 38.

Hyperglycaemia is the main culprit responsible for impaired angiogenesis and wound healing process 5, 6. In our study, treatment with FA in diabetic rats showed significant decrease in blood glucose levels which is in agreement with previous reports 10.

Collagen is the predominant extracellular protein in the granulation tissue of a healing wound and there is a rapid increase in the synthesis of this protein in the wound area soon after an injury 39. Breakdown of collagen liberates free hydroxyproline and its peptides. Measurement of the hydroxyproline is as an index of collagen turnover 40. In wound healing process, sudden increase in collagen was observed at day 7 and epithelisation peaks in 48 h under optimal conditions 41. In this study, diabetic control rats showed substantial decrease in hydroxyproline content which was reflected as very little or no formation of granulation tissue on diabetic wounds. Whereas significant increase in hydroxyproline content was observed in both orally and topically FA treated groups which was further reflected as increased granulation tissue formation on diabetic wounds.

Hexosamine is a component of the ground substance required for the synthesis of the extracellular matrix and thus for proper wound healing. In general, the level of hexosamine increases between 7th and 12th post‐wounding day and then decreases slowly 42, 43. We evaluated hexosamine content in granulation tissues of excision wounds in order to monitor the wound healing process. FA significantly increased hexosamine content in both orally and topically treated groups compared to the diabetic control rats indicating improved extracellular matrix synthesis and thus proper wound healing.

Trace elements such as zinc and copper are components of several metalloenzymes which are required in wound healing phenomenon. Because of zinc's role in collagen synthesis (the main protein of connective tissue) and in the multiplication of many cells, such as epithelial cells and fibroblasts, it plays an important role in the healing of wounds. As powerful antioxidants, zinc can prevent cell damage and stabilise cell wall structure 44. We have observed significant decrease in serum zinc levels in diabetic control rats which was significantly improved in diabetic rats treated orally with FA.

Moreover, diabetic control group showed significant decrease in serum copper level which is an extracellular cofactor required for collagen and elastin cross‐linking thus plays an important role in wound repair phenomenon 45. Administration of FA in diabetic rats showed significant elevation in serum copper levels thus assisting in collagen and elastin synthesis.

In diabetes, there is increase in oxidative stress and the ROS which delays wound healing process in diabetic condition 34. In diabetic condition there occurs increased LPO and MDA, a secondary product of LPO used as a biomarker to measure the level of oxidative stress in an organism. It is produced by the degradation of polyunsaturated lipids by ROS 46. In this study, oral administration of FA significantly decreased the serum MDA levels, whereas SOD, GSH and CAT levels were significantly increased as compared to diabetic control rats.

Nitric oxide is known for its stimulatory effect on cell proliferation, angiogenesis and regeneration 47. NO increases fibroblast proliferation and thereby collagen production in wound healing. l‐Arginine and nitric oxide are required for proper cross‐linking of collagen fibres, via proline, to minimise scarring and maximise the tensile strength of healed tissue 48. Diabetics exhibit reduced ability to generate nitric oxide from l‐arginine 49. FA possesses angiogenesis activity 14. In this study, there was a significant increase in plasma NO level in diabetic rats treated orally with FA.

The diabetic control group showed reduction in body weight due to increased muscle wasting and due to the loss of tissue proteins which is in agreement with the previous reports 50, 51. Orally treated FA groups prevented weight loss because of diabetes and restored body weight indicating improved wound healing process.

In excision wound, FA enhanced the wound contraction compared with control group. The wound contraction rate of the FA may be due to collagen deposition, elevation in Zn and Cu levels and rapid maturation of granulation tissue. Both oral and topical treatments of FA showed faster healing when compared with diabetic control groups. There was a significant reduction in wound size from day 8 onwards in FA orally and topically treated animals indicating improved wound healing process.

In the histological evaluation of diabetic control rats showed marked epidermal necrosis, increased inflammatory cells migration and bacterial colonies. This indicates impaired wound healing process in diabetic control rats. However, treatment with FA orally for 2 weeks showed mature granulation tissue formation and regeneration of epidermis followed by hyperkeratosis thus, improved healing of diabetic wound. Further, FA topically treated group showed presence of granulation tissue and increased dilation of blood vessels showing positive effects on wound healing process, however, no sign of hyperkeratosis was observed (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Photographs of haematoxylin and eosin staining on 14th day in wound granulation tissue under 100× magnification power using light microscope. (a) epidermal necrosis, (b) immature granulation tissue area, (c) bacterial colonies, (d) inflammatory cells, (e) mature granulation tissue, (f) blood cells and (g) hyperkeratosis.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that FA is effective in promoting wound healing in diabetic rats. FA effectively inhibited the LPO and elevated the CAT, SOD, GSH and NO levels along with the increase in serum Zn and Cu levels probably aiding the wound healing process.

References

- 1. Whiting D, Guariguata L, Weil C, Shaw J. IDF diabetes atlas: global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2011 and 2030. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2011;94:311–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Friedman E. Evolving pandemic diabetic nephropathy. Rambam Maimonides Med J 2010;1:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tam J, Lau K, Liu C, To M, Kwok H, Lai K, Lau C, Ko C, Leung P, Fung K, Lau C. The in vivo and in vitro diabetic wound healing effects of 2‐herb formula and its mechanisms of action. J Ethnopharmacol 2011;134:831–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Doxey D, Nares S, Park B, Trieu C, Cutler C, Lacopino A. Diabetes‐induced impairment of macrophage cytokine release in a rat model: potential role of serum lipids. Life Sci 1998;63:1127–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Duraisamy Y, Slevin M, Smith N. Effect of glycation on basic fibroblast growth factor induced angiogenesis and activation of associated signal transduction pathways in vascular endothelial cells: possible relevance to wound healing in diabetes. Angiogenesis 2001;4: 277–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Herrick S, Sloan P, McGurk M. Sequential changes in histologic pattern and extracellular matrix deposition during the healing of chronic venous ulcers. Am J Pathol 1992;141:1085–95. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Aliyeva E, Umur S, Zafer E, Acigoz H. The effect of polylactide membrane on the levels of reactive oxygen species in periodontal flaps during wound healing. Biomaterials 2004;25:4633–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Greenhalgh D. Wound healing and diabetes mellitus. Clin Plast Surg 2003;30:37–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Karthikeyan S, Kanimozhi G, Rajendra N, Mahalakshmi N. Radiosensitizing effect of ferulic acid on human cervical carcinoma cells in vitro. Toxicol Vitro 2011;25:1366–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jung E, Kim S, Hwang I, Ha T. Hypoglycemic effects of a phenolic acid fraction of rice bran and ferulic acid in C57BL/KsJ db/db mice. J Agric Food Chem 2007;55:9800–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lin F, Lin J, Ravindra D, Gupta A, James A, Burch M. Ferulic acid stabilizes a solution of vitamins C and E and doubles its photoprotection of skin. J Invest Dermatol 2005;125:826–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cheng Y, Yang S, Yang K, Chen M, Lin F. The effects of ferulic acid on nucleus pulposus cells under hydrogen peroxide‐induced oxidative stress. Process Biochem 2011;46:1670–77. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gohil KJ, Kshirsagar SB, Sahane RS. Ferulic acid‐a comprehensive pharmacology of an important bioflavonoid. Int J Pharm Sci Res 2012;3:700–10. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lin CM, Chiu JH, Wu IH, Wang BW, Pan CM, Chen YH. Ferulic acid augments angiogenesis via VEGF, PDGF and HIF‐1α . J Nutr Biochem 2010;21:627–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wang J, Yuan Z, Zhao H, Ju D, Chen Y, Chen X, Zhang J. Ferulic acid promotes endothelial cells proliferation through up‐regulating cyclin D1 and VEGF. J Ethnopharmacol 2011;137:992–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ou L, Kong L, Zhang X, Niwa M. Oxidation of ferulic acid by Momordica charantia. Peroxidase and related anti‐inflammation activity changes. Biol Pharm Bulletin 2003;26:1511–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tetsuka T, Baier L, Morrison A. Antioxidants inhibit interleukin‐1 induced cyclooxygenase and nitric oxide synthase expression in rat mesangial cells: evidence for posttranscriptional regulation. J Biol Chem 1996;271:1168–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Merkl R, Hradkova I, Filip V, Smidrkal J. Antimicrobial and antioxidant properties of phenolic acids alkyl esters. Czech J Food Sci 2010;28:275–9. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Balasubashini SM, Rukkumani R, Viswanathan P, Menon VP. Ferulic acid alleviates lipid peroxidation in diabetic rats. Phytother Res 2004;18:310–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shivananda BN, Lexley PP, Dale M. Wound healing activity of Carica Papaya L. in experimentally induced diabetic rats. Indian J Exp Biol 2007;45:743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Senthil MK, Kirubanandan S, Sripriya R. Triphala promotes healing of infected full thickness dermal wound. J Surg Res 2008;22:89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Woessner JF. The determination of hydroxyproline in tissue and protein samples containing small portion of this imino acid. Arch Biochem Biophys 1961;93:440–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Johansen PG, Marshall RD, Neuberger A. Carbohydrates in protein: the hexose, hexosamine, acetyl and amide‐nitrogen content of hen's‐egg albumin. Biochem J 1960;77:239–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sunar F, Baltaci AK, Ergene N, Mogulkoc R. Zinc deficiency and supplementation in ovariectomized rats: there effect on serum estrogen and progesterone levels and their relation to calcium and phosphorus. Pak J Pharm Sci 2009;22:150–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Uchiyama M, Mihara M. Determination of malonaldehyde in tissues by thiobarbituric acid test. Anal Biochem 1978;86:271–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kono Y. Generation of superoxide radical during auto oxidation of hydroxylamine and an assay for superoxide dismutase. Arch Bichem Biophys 1978;186:189–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sedlak J, Lindsay RH. Estimation of total protein bound and nonprotein sulfhydryl groups in tissue with ellmann's reagent. Anal Biochem 1968;25:192–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Aebi H. Catalase in vitro . Methods Enzymol 1984;105:121–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Green LC, Wagner DA, Glogowaki J, Skipper PL, Wishnok JS, Tannenbaum SR. Analysis of nitrate, nitrite and [15N]nitrate in biological fluids. Anal Biochem 1982;126:131–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rossing P, Hommel E, Smidt UM, Parving HH. Reduction in albuminuria predicts a beneficial effect on diminishing the progression of human diabetic nephropathy during anti‐hypertensive treatment. Diabetologia 1994;37:511–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pattanayak SP, Sunita P. Wound healing, antimicrobial and antioxidant potential of Dendrophthoe falcate (L.f.) Ettingsh. J Ethnopharmacol 2008;120:241–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Glynn L. The pathology of scar tissue formation. Vol. 25. Amsterdam: Holland Biomedical Press, 1981:215–220. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Clark R, Henson P. Molecular and cellular biology of wound repair. New York: Plenum Press, 1996:46–52. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Martin A. The use of antioxidants in healing. Dermatol Surg 1996;4: 156–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Trautmann A, Toksoy A, Engelhardt E, Brocker EB, Gillitzer R. Mast cell involvement in normal human skin wound healing: expression of monocyte chemoattractant protein‐1 is correlated with recruitment of mast cells which synthesize interleukin‐4 in vivo. J Pathol 2000;190:100–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. McMurry J. Wound healing with diabetes mellitus. Better glucose control for better wound healing in diabetes. Surg Clin North Am 1984;64:769–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Huysman E, Mathieu C. Diabetes and peripheral vascular disease. Acta Chir Belg 2009;109:587–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hehenberger K, Kratz G, Hansson A, Brismar K. Fibroblasts derived from human chronic diabetic wounds have a decreased proliferation rate, which is recovered by the addition of heparin. J Dermatol Sci 1998;16:144–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chithra P, Sajithlal GB, Chandrakasan G. Influence of aloe vera on the healing of dermal wounds in diabetic rats. J Ethnopharmacol 1998;59:195–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pradhan D, Panda P, Tripathy G. Wound healing activity of aqueous and methanolic bark extracts of Veronica arborei in wistar rats. Nat Prod Res 2009;8:6–11. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Graber AM. Wound management. General Surg 2002;22–34. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nayak S, Nalabothu P, Sandiford S, Bhogadi V, Adogwa A. Evaluation of wound healing activity of Allamanda cathartica. L. and Laurus nobilis. L. extracts on rats. BMC Complement Altern Med 2006;6:8–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chaudhari M, Mand S. Evaluation of phytoconstituents of Terminalia arjuna for wound healing activity in rats. Phytother Res 2006;20:799–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sandstead HH, Lanier Jr. VC, Shephard GH, Gillespie DD. Zinc and wound healing: effects of zinc deficiency and zinc supplementation. Am J Clin Nutr 1970;23:514–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gadi B. Copper's role in wound healing. Biomaterials 2004;20: 201–209. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rahimi R, Nikfar S, Larijani B, Abdollahi M. A review on the role of antioxidants in the management of diabetes and its complications. Biomed Pharmacother 2005;59:365–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Stallmeyer B, Kampfer H, Kolb N, Pfeilschifter J, Frank S. The function of nitric oxide in wound repair: inhibition of inducible nitric oxide‐synthase severely impairs wound reepithelialization. J Invest Dermatol 1999;113:1090–1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kei O. Exogenous nitric oxide enhances the synthesis of type I collagen and heat shock protein by normal human dermal fibroblasts. J Dermato Sci 2006;41:121–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Cameron E, Cotter A, Archibald V, Dines C, Maxfieid K. Anti‐oxidant and pro‐oxidant effects on nerve conduction velocity, endoneurial blood flow and oxygen tension in non‐diabetic and streptozotocin‐diabetic rats. Diabetologia 1994;37:449–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bhutada P, Mundhada Y, Bansod K, Bhutada C, Tawari S, Dixit P, Mundhada D. Ameliorative effect of quercetin on memory dysfunction in streptozotocin‐induced diabetic rats. Neurobiol Learn Mem 2010;94:293–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Srinivasan K, Viswanad B, Asrat L, Kaul CL, Ramarao P. Combination of high‐fat diet‐fed and low‐dose streptozotocin‐treated rat: a model for type 2 diabetes and pharmacological screening. Pharmacol Res 2005;52:313–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]