Abstract

Increasing pressure on health care budgets highlights the need for clinicians to understand the true costs of wound care, in order to be able to defend services against indiscriminate cost cutting. Our aim was to develop and test a straightforward method of measuring treatment costs, which is feasible in routine practice. The method was tested in a prospective study of leg ulcer patients attending three specialist clinics in the UK. A set of ulcer‐related health state descriptors were defined on the basis that they represented distinct and clinically relevant descriptions of wound condition [‘healed’, ‘progressing’; ‘static’‘deteriorating; ‘severe’ (ulcer with serious complications)]. A standardised data‐collection instrument was used to record information for all patients attending the clinic during the study period regarding (i) the health state of the ulcer; (ii) treatment received during the clinic visit and (iii) treatment planned between clinic visits. Information on resource use was used to estimate weekly treatment costs by ulcer state. Information was collected at 827 independent weekly observations from the three study centres. Treatment costs increased markedly with ulcer severity: an ulcer which was ‘deteriorating’ or ‘severe’ cost between twice and six times as much per week as an ulcer which was progressing normally towards healing. Higher costs were driven primarily by more frequent clinic visits and by the costs of hospitalisation for ulcers with severe complications. This exercise has demonstrated that the proposed methodology is easy to apply, and produces information which is of value in monitoring healing and in potentially reducing treatment costs.

Keywords: Costs, Ulcers, Wound care, Wound healing

Introduction

Early in 2009, the Chief Executive of the UK National Health Service (NHS), David Nicholson, told the NHS that it should plan to save £20 billions in the 2012–2014 spending round, on top of the £2·3 billion savings already required in the period upto 2011 (1). These trends are not unique to the UK. Increasing pressure on health care budgets highlights the need to ensure that available resources are used efficiently. However, it is critical at this time for clinicians to understand the true costs of wound care in order to be able to defend services against indiscriminate cost‐cutting. In particular, it is important to understand the difference between the cost of dressings and materials (which is visible) and the other costs of healing an ulcer, such as clinician time and inpatient bed‐days, which tend to be hidden. It is also important to know how the total costs of healing increase with the incidence of delayed healing, infection and other complications. At the same time, it is important to be able to demonstrate positive patient outcomes. Understanding the impact of delayed healing on outcomes and costs, highlights the importance of ensuring that treatment is effective and that wound care services are adequately resourced.

We are a long way from this level of understanding. Costing individual patient episodes over a number of weeks of treatment is time consuming and can be complicated. The conventional approach is to record details of all major resources consumed (clinician time, dressings, antibiotics, analgesics, investigations, hospital admission and surgical interventions) at each patient contact over the period from first presentation to wound healing. As a result, there are few costing studies carried out outside the limited context of a clinical trial, where complex patients or those suffering from adverse events are often excluded, with the result that costs may not be representative of normal clinical practice.

Our aim was to develop and test a different approach to collecting information on treatment costs, which is more straightforward and more likely to be feasible in routine practice. The method has been tested in a prospective study of leg ulcer patients attending three specialist clinics in the UK.

Methods

The first stage was to define a set of ulcer‐related health state descriptors to classify the healing status of an ulcer. Health states should be clinically meaningful and should convey information that is relevant to treatment choices. Health state descriptors were agreed by the clinical members of the project team on the basis that they represented distinct and clinically relevant descriptions of wound condition. Monitoring the health state of the ulcer on a weekly basis is a relatively straightforward way to provide early warning of healing delays, and to signal the need for further investigation. We defined five health states relevant to leg ulcer treatment:

-

1

HS1. Healed – Skin is intact

-

2

HS2. Unhealed grade 1: progressing – Ulcer is progressing towards healing

-

3

HS3. Unhealed grade 1: static – Ulcer is neither healing nor deteriorating

-

4

HS4. Unhealed grade 1: deteriorating – Ulcer is deteriorating (e.g. increasing in size, exudate or odour; surrounding skin is deteriorating)

-

5

HS5. Unhealed grade 2: severe – Ulcer is infected or with other complications which may require hospital admission and/or surgical intervention

The health state also conveys information about the likely costs of treatment. Weekly costs are expected to be similar between ulcers in the same health state and different between ulcers in different health states. The second stage of the costing exercise was to estimate weekly resource use and costs for each health state from information collected prospectively on a sample of patients.

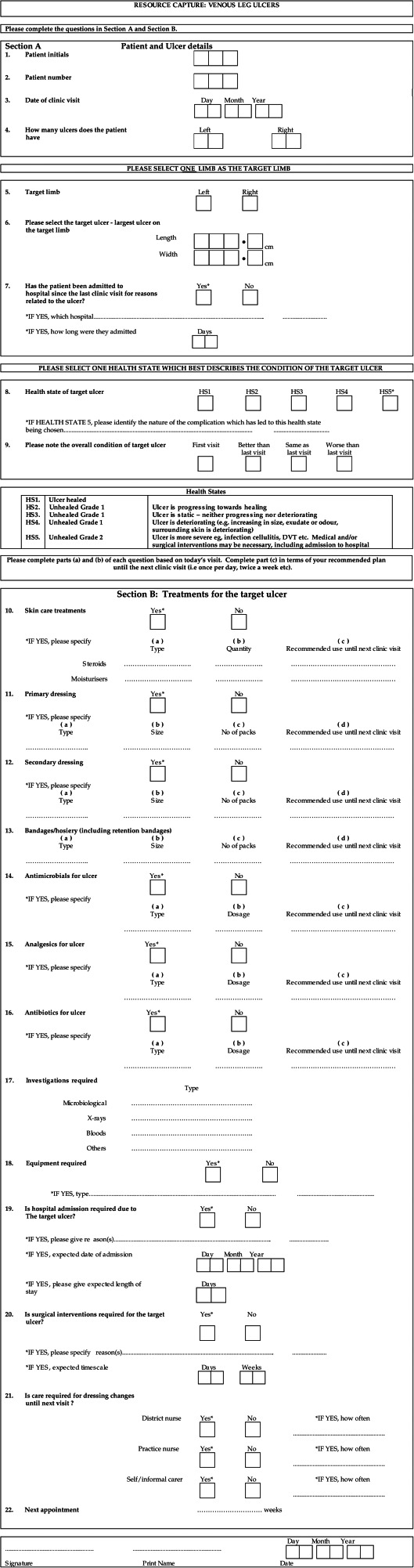

In order to test the methodology, a pilot study was conducted in one specialist leg ulcer clinic. A standardised data‐collection instrument was used to record information for all patients attending the clinic on (i) the health state of the ulcer, (ii) treatment received during the clinic visit and (iii) treatment planned between visits, including ulcer‐related hospital admission. The data‐collection form is shown in the Appendix. Where a patient had more than one ulcer, information was recorded for the largest (reference) ulcer. For patients admitted to hospital for the treatment of the reference ulcer, information was retrieved on length of stay. The main aim was to establish whether the proposed health states were meaningful to clinicians and could be readily distinguished. Data were recorded for a total of 274 clinic attendances on 100 patients. Health state was recorded in 99% of cases and details of treatment and resource use was complete in 97% of cases. Clinicians did not have any difficulty in distinguishing between health states or in recording treatment details.

The results of the pilot study suggested that the health states were meaningful and that the data‐collection instrument was appropriate for its purpose. The study was extended to include two further specialist centres in the UK in order to increase the number of observations and to obtain a reasonable number of observations on each health state. All patients attending a leg ulcer clinic were recruited to the study. Information was recorded routinely on the health state of the ulcer and on treatments received during the visit. Information on treatments to be received between clinic attendances was based on the recommendations of the clinic nurse for the period until the next scheduled visit.

The original research was carried out in 2000, with a view to linking cost estimates with healing outcomes derived from a separate study. In the original study, resource costs were based on representative national NHS prices for the 1999/2000 financial year. Where ever possible, we have updated the costs to 2008/2009 prices using the same data sources as were used in the original study. Prices of skin care treatments, dressings, bandages, compression hosiery, antimicrobials, analgesics, antibiotics and other materials were taken from the Drug Tariff (November 2009) (2) or British National Formulary (September 2009) (3). In the absence of national average costs for investigations (X‐rays, blood tests, biopsy, scan, microbiology) these were valued in the original study at local costs from one of the study centres. These costs have not been updated to 2008/2009 values. Average NHS costs of hospital outpatient attendance, district nurse home visits and practice nurse consultations were taken from Unit Costs of Health and Social Care, 2008 (4). An average inpatient cost of £290 per day was calculated by taking a weighted average of daily rates imputed from 2005 to 2006, National Reference Costs for non‐elective inpatients in Healthcare Resource Groups (HRG) for major and minor skin infections (codes J42 and J45) (5).

Results

Including the pilot data, information was collected on a total of 827 independent observations from the three study centres (Table 1). Observations were independent in the sense that they were not linked to particular patients. Observations on healed ulcers (111) comprised 13·4% of the total. Among unhealed ulcers, 347 (48·5%) were progressing; 229 (32%) were static; 122 (17%) were deteriorating and 18 (2·5%) were ulcers with complications. The relatively low proportion of observations on healed patients is not a reflection of the rate of healing, but rather of the fact that the data‐collection period was short (2–3 weeks) and the fact that once an ulcer was healed the same patient was unlikely to be seen again within the study period.

Table 1.

Average treatment costs per patient per week by ulcer health state and study centre, and number of observations by health state and study centre

| Health state | All observations | Centre 1 | Centre 2 | Centre 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| £ per patient | Observations | £ per patient | Observations | £ per patient | Observations | £ per patient | Observations | |

| Healed | 6·04 | 111 (13·4%) | 2·57 | 13 (5·5%) | 2·57 | 8 (4·3%) | 6·85 | 90 (22·2%) |

| Progressing | 87·59 | 347 (41·9%) | 98·64 | 96 (40·3%) | 97·71 | 80 (43·5%) | 76·58 | 171 (42·2%) |

| Static | 100·27 | 229 (27·7%) | 113·73 | 73 (30·7%) | 108·17 | 61 (33·2%) | 84·92 | 95 (23·5%) |

| Deteriorating | 159·45 | 122 (14·8%) | 161·62 | 51 (21·4%) | 136·63 | 25 (13·6%) | 169·39 | 46 (11·4%) |

| Severe | 637·15 | 18 (2·2%) | 1280·22 | 5 (2·1%) | 201·30 | 10 (5·4%) | 1018·08 | 3 (0·7%) |

| 827 (100%) | 238 (100%) | 184 (100%) | 405 (100%) | |||||

Weekly costs were different between different health states, and the relationship was as expected – costs increased with increasing severity (Table 1). In general, costs were consistent between centres. The weekly equivalent cost for patients with a healed ulcer (£6·04) was based on the frequency of routine follow‐up assessment visits. Costs were higher in centre 3 because healed patients were reviewed quarterly for the first year, and then annually as in the other centres. The average weekly cost of treating open unhealed ulcers increased from £87·59 (HS2) (range £76·58–£98·64) to £637·15 (HS5) (range £201·30–£1280·22). In this latter group, the variation in costs between centres was relatively large because of the small number of observations and the significant impact of hospitalisation costs in this group.

The main determinants of costs varied by health state (Table 2). For patients with a healed ulcer (HS1), costs were dominated by compression hosiery and clinic assessment visits. For ulcers which were progressing or static, costs were dominated by nurse time, proxied by outpatient clinic and district nurse visits. The cost of dressings and bandages mirrored the frequency of nursing visits. The balance between outpatient attendances and district nurse visits differed between centres depending on local practice.

Table 2.

Average treatment costs per patient per week by ulcer health state and by sources of cost

| Health state | Healed | Progressing | Static | Deteriorating | Severe | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resources used | £ per patient | % | £ per patient | % | £ per patient | % | £ per patient | % | £ per patient | % |

| Skin care | 0·04 | a | 0·23 | a | 0·19 | a | 0·65 | a | 0·20 | a |

| Dressings/bandages | – | – | 9·99 | 11·4 | 11·07 | 11·0 | 11·60 | 7·3 | 16·11 | 2·5 |

| Compression hosiery | 1·65 | 27·4 | 0·02 | a | 0·01 | a | 0·02 | a | – | – |

| Antimicrobials | – | – | 0·35 | a | 0·28 | a | 0·27 | a | 1·17 | a |

| Analgesics for wound | – | – | 0·34 | a | 0·40 | a | 0·40 | a | 0·51 | a |

| Antibiotics for wound | – | – | 0·10 | a | 0·30 | a | 2·44 | a | 6·40 | a |

| Investigations | – | – | 1·10 | a | 4·53 | 4·5 | 6·40 | 4·0 | 226·31 | 35·5 |

| Equipment | – | – | 0·07 | a | 2·50 | 2·5 | 0·07 | a | 0·05 | a |

| Hospital admission | – | – | 3·81 | 4·4 | 1·99 | 2·0 | 39·79 | 25·0 | 295·68 | 46·4 |

| District nurse visits | – | – | 25·62 | 29·3 | 30·15 | 30·1 | 40·85 | 25·6 | 46·51 | 7·3 |

| Practice nurse visits | – | – | 1·61 | a | 1·37 | a | 0·52 | a | 1·38 | a |

| Outpatient clinic visits | 4·35 | 72·0 | 44·35 | 50·6 | 47·48 | 47·4 | 56·44 | 35·4 | 42·83 | 6·7 |

| 6·04 | 99·4 | 87·59 | 95·7 | 100·27 | 97·5 | 159·45 | 97·3 | 637·15 | 98·4 | |

Values are <2.

HS2 (Progressing): In centre 1 patients were seen approximately weekly at the specialist outpatient clinic with no additional district nurse visits. In centres 2 and 3 patients were reviewed at the clinic approximately once every 3 weeks (once per 21–22 days), with 60–70% receiving additional district nurse home visits approximately weekly.

HS3 (Static): In centre 1, patients were seen approximately weekly at the clinic with no district nurse visits in‐between. In centres 2 and 3, patients were reviewed at a clinic approximately once every 2 weeks (once per 12–19 days), with 60–70% receiving additional district nurse visits approximately weekly.

For ulcers which were deteriorating or severe, higher costs were driven by the costs of investigations and hospital admission, combined with more frequent district nurse home visits. The frequency of outpatient clinic attendances was approximately the same as for patients in HS3, but with more frequent district nurse home visits – 70–80% daily or every 2 days. In the severe health state (HS5), investigations accounted for 35·5% and hospitalisation for 46·4% of total cost.

Our results illustrate the importance of early recognition of health state in order to prevent ulcer complications. Overall treatment costs per patient are a function of the number of treatment weeks (time to healing), and the balance between health states. Delayed healing, infection and other complications increase costs by increasing treatment weeks, and also by increasing the resource intensity of treatment: more nursing visits, more investigations and a higher rate of hospitalisation. The average weekly cost of treating an ulcer which is deteriorating is approximately twice as high as the cost of treating an ulcer which is progressing normally. The weekly cost of treating an ulcer which becomes severe is seven times as high. Resources devoted to maintaining a normal healing progression through early diagnosis, regular specialist assessment and monitoring, and early referral for investigation or inpatient treatment, can avoid significant additional costs later in the treatment episode. These results are broadly in line with Tennvall & Hjelmgren, who state that hard to heal ulcers take 33–44% more nursing time, 100% higher staff costs and 100% higher product cost than an ulcer which is progressing (6).

Discussion

Our aim was to develop and test a relatively straightforward method for obtaining information on treatment costs which would be feasible in routine practice. The results of the exercise suggest that there is value in the proposed approach. The first stage is to define a set of ulcer‐related health states which are clinically meaningful, and which are easy to distinguish and record. Health state assessment is based on observation and clinical judgement. Recording requires ticking of one box only, and is not time‐consuming. Even this stage on its own has potential benefits. Monitoring the health state of the ulcer on a regular basis provides early warning of healing delays and may signal the need for further investigation, or a change in treatment. Regular recording of health states establishes a healing profile for each ulcer which can be used to identify, for example, time to healing or the impact of ulcer complications on healing time. Better understanding of the potential cost implications of ulcer complications is one way to illustrate the value of a specialist leg ulcer service.

The second stage is to collect information prospectively for a sample of patients on the resources consumed during treatment. The sample should be representative of the overall population of patients, and should be large enough that it contains a reasonable number of observations on each health state. It is not necessary to record every item of resource use, only those items which are significant in terms of cost. Our results suggest that district nurse home visits, specialist clinic attendances, dressings and bandages, investigations, and hospital length of stay are likely to be the most important. On reflection we should also have included the costs of surgical procedures, and today the cost of antimicrobials may also be significant. It is very important to measure resources used between clinic assessments, and to obtain information on hospital admission. We used representative national prices to value resource use, but it may be equally relevant to use local prices where these are available.

The final stage would be to combine health state profiles from the records of individual patients with estimates of weekly treatment costs for each health state to produce estimates of the cost of individual patient episodes of treatment. This type of information could be used to estimate expected costs to healing by patient and/or ulcer characteristics, or the cost impact of complications over the whole treatment episode.

There are many limitations of this work. Our exercise was limited to testing a costing methodology, and we recognise that costs have limited relevance in the absence of information about patient outcomes. However, we believe that the methodology could be used to facilitate regular monitoring of ulcer healing and to readily identify problems in healing which need further investigation. The same methodology could also be applied to bring together patient outcomes and costs through routine recording of health state details. The original study was carried out in 2000, but we believe that clinical practice, and hence patterns of resource use, have not changed significantly in the intervening period. The accuracy of our estimates of weekly costs may be limited by the fact that we did not verify recorded information from independent sources, and we did not check that the treatment planned between clinic visits was actually provided. The study was carried out in centres providing specialist leg ulcer services and for this reason cost estimates may not be representative of typical practice in the UK.

Data Collection Form

References

- 1. Health Service Journal . 16th September 2009. and 12th November 2009 [WWW document]. URL www.hsj.co.uk.

- 2. NHS in England & Wales. Drug Tariff, November 2009. [WWW document]. URL www.nhsbsa.nhs.uk/prescriptions

- 3. Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. British National Formulary, 58, September 2009. [WWW document]. URL www.bnf.org

- 4. Unit costs of health and social care 2008 , compiled by Lesley Curtis. Personal Social Services Research Unit, University of Kent at Canterbury [WWW document]. URL www.pssru.ac.uk

- 5. UK Department of Health . National Health Service Reference Costs 2005/06 [WWW document]. URL www.dh.gov.uk/en/publicationsandstatistics/publications

- 6. Tennvall GR, Hjelmgren J. Annual costs of treatment for venous leg ulcers in Sweden and the United Kingdom. Wound Repair Regen 2005;13:13–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]