Abstract

This article presents the results of an international 2 stage Delphi survey carried out via e‐mail to achieve consensus as to the most effective postoperative wound management to prevent blistering and other complications. Seventeen prospective participants were invited to be members of the Delphi Panel of which 13 agreed to be involved. The panel suggested that an ideal wound dressing would conform easily to the wound, be easy to apply and remove, allow for swelling and minimise pain on removal. Participants were in agreement that the primary wound dressing should be left in situ for as long as possible, providing there was no excessive oozing or signs of infection. The authors recognise that the Delphi Panel was relatively compact; however, the study arguably provides some useful data that can be used to identify the consequences of wound blistering and important factors that need to be considered when choosing a wound dressing to prevent blistering.

Keywords: Delphi, Orthopaedic, Prevention, Wound blistering

INTRODUCTION

A limited amount of studies have examined the effect of different dressings on wound healing with no conclusive recommendations (1). However, we must be aware that irrespective of the healing properties of a dressing, there may at times be unwanted consequences of an adhesive dressing, for example, development of blisters on the peri wound skin area. This article presents results of a two‐round Delphi survey conducted by an international panel of experts exploring the prevention of postoperative wound blistering.

The incidence of superficial wound problems such as skin blistering is a commonly reported problem, especially in orthopaedic surgery 2, 3. Blistering can cause increased pain, delayed wound healing and increased susceptibility to wound infection, as the integrity of the skin has been breached (4). There is currently conjecture in the literature as to whether dressing choice has an effect on wound complication rates 1, 5. A prospective clinical audit of orthopaedic wound blistering in Scotland, including more than 1000 hip and knee arthroplasties in 2006, identified that skin blistering was common following the use of traditional adhesive absorbent dressings and showed a blister rate of 19·5% (6). Tape‐related injuries causing blistering after hip surgery have been reported as 21·4% (7). Jester et al.(8) reported the incidence of blistering, using a variety of dressings, at 13%, whereas Cosker et al.(3) reported postoperative blistering rates as ranging from 6% to 24% depending on the dressing used.

Why is this study important?

Surgical patients who develop postoperative wound complications, including blistering, risk a prolonged hospital stay which can adversely affect morbidity/mortality rates (1), and can increase costs associated with health care procedures because of increased wound dressing use, medications and nursing care input for wound care. There is a paucity of published studies specifically in the field of wound blistering discussing the treatment of wound blisters in post operative patients. However, few of these studies examine prevention of wound blistering. The results of this Delphi survey offer an insight into effective use of wound dressings and consensus of opinion as to the ideal properties of wound dressings to prevent blistering.

LITERATURE REVIEW

A search of published literature was undertaken exploring the following databases: The Cochrane Library, MEDLINE (1950 to June 2011), EMBASE (1974 to June 2011), CINAHL (1982 to June 2011) using the key words wound blistering, orthopaedics and postoperative; ten papers identified were pertinent to our research, examining prevention of wound blisters. A number of studies investigated the incidence of wound blisters occurring postoperatively in acute settings rather than prevention of wound blisters, three reviews examined prevention and treatment strategies, two of which were specific to wound blisters 1, 5. Collins(5) determined that there was no consistency in the treatment and dressing choice of postoperative orthopaedic wounds, with no particular set of guidelines applicable with a perceived distinct gain. Polatsch et al.(7) suggested from their review that incidence of wound blisters was reported haphazardly in the literature and therefore performed their own retrospective audit from case notes of patients who had undergone surgery for hip fracture. They identified a high incidence of tape‐related blisters (21·4%) that they suggested was specific to the type of tape used to secure the dressing rather than the actual wound dressing.

A clinical audit of 116 postoperative patients who had undergone knee arthroplasty during a 1‐year period, using a standardised dressing protocol, was recorded (9). Bhattacharyya reported 6% of patients developing a blister and stated that this was a result of poor dressing choice. Similarly, Jester et al.(8)reported in their audit of knee and hip arthroplasty patients, a prevalence of 13% for postoperative wound blisters. They performed analysis of variables within this audit to determine possible explanations of causation, but found no statistical differences for choice of dressing. They tentatively concluded that wound conforming (elastic) dressings may have a beneficial effect in the prevention of blister formation. Gupta et al.(4) examined 100 postoperative hip and knee surgery patients and established incidence of blisters at approximately 20%. However, they reported considerable variation among three dressing choices, in a quasi‐experimental study. In a prospective study of patients undergoing hip or knee surgery, the postoperative blistering rate ranged from 6% to 24% depending on the dressing used (3). Of the remaining studies reviewed, two did not focus on orthopaedic surgery and one had too small patient numbers to provide meaningful data to be included in this review 9, 10, 11.

The review by Tustanowski(1) identified that wound blistering could be associated with a number of factors: movement of the wound site, choice of dressing, tape use, age, gender, type of incision, medications, comorbidity and cost‐effectiveness of dressings(1). However, an overall conclusion could not be reached, based on this critical review, other than the accepted principles of good postoperative wound management and standard properties of wound dressings. It could be argued that calls for further comparative studies of wound dressings will only continue to provide equivocal results. Therefore, it was considered that the way forward was to achieve consensus between experts and practitioners as to the most clinical and cost‐effective dressings and postoperative wound management to prevent blistering and other complications. An online Delphi survey was devised and implemented to address this, and to form a consensus opinion as to practise best in the prevention of orthopaedic wound blistering.

AIMS

To establish an expert reference group (ERG) to consider the problem of wound blistering.

To develop and evaluate expert consensus opinion in the prevention and management of orthopaedic wound blistering.

To establish a working clinical and cost‐effective guideline and benchmarks for the prevention of wound blistering.

METHODS

There were two rounds of the Delphi process held via e‐mail. All participants remained anonymous to each other, but did receive data analysis from the first round of questionnaires prior to undertaking the second round. The Delphi surveys' aim was to establish a global ERG and achieve consensus for statement and guideline development on the prevention and management of wound blistering. This consisted of four steps, detailed below.

Step 1: Clarification of the research problem/clinical question

Initial consultation and discussion took place between known experts in the field of wound blistering from health care practitioners, academic researchers and industry personnel. This discussion determined the clinical question to be answered.

Step 2: Identification of resources and members of the ERG

Individuals with a known interest in the field of wound care were invited to join the ERG via an e‐mail request from the lead academic researcher.

Step 3: Establishing the initial round

The initial round took the form of a survey of all the ERG members using open‐ended questions to act as probes. The process and aim of the survey was to finalise the clinical question to be answered, discovery of opinions and determination of the most important issues (benchmarks) for the prevention of wound blistering.

Step 4: Establishing the method and process of following rounds

Following the initial round, results were collated and presented to the ERG for agreement and formulation of initial benchmarks. The next stage was a second survey asking for additional ideas, clarifications and elaborations based on the initial survey responses. The second round of surveys was returned to the researchers for analysis, clarifications and elaborations. The responses were ranked and clarified.

It is envisaged that because of the continuous nature of research data becoming available, the ERG will continue to evaluate and refine the consensus guideline and benchmarks via electronic communication.

THE DELPHI SURVEY

Sample

Seventeen prospective participants were invited to be members of the Delphi Panel from England, Wales, Ireland, Scotland, Scandinavia, India, Australia and the USA. Of the 17 people invited, 13 agreed to be involved. There were no respondents from India. Participants were drawn from an expertise‐based purposive sample, including orthopaedic medical staff, tissue viability nurse specialists, orthopaedic nurses, nurse academics and researchers. Although the number of respondents was low, we do not believe this is a concern. Of the 13 respondents, all 13 completed the first round but only 9 completed the second round of questionnaires.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was received from the School of Human and Health Sciences Research and Ethics Panel, University of Huddersfield. Additionally, Leeds Research and Ethics Committee were contacted concerning permissions. They advised that the Delphi survey did not require NHS associated approval.

Data analysis

Survey data from both rounds were entered into PASW (IBM SPSS, New York, NY) version 18. Descriptive statistics relating to respondents' opinions of treatment of wound blistering and wound dressing characteristics were derived for each data set independently, with the results from the second round of the analysis being additionally used as a cross‐check against results from the first round, where appropriate. Because of the small size of the samples, inferential statistics were not derived for either round of the survey.

RESULTS

The first round of questions sought to explore the incidence of wound blistering, dressings used immediately postoperatively for joint replacement operations and which professional group assessed the wound and decided on the first postoperative dressing.

First round analysis

Incidence of wound blistering following total joint replacement surgery

During the first round of questions, respondents were asked to state the number of joint replacements undertaken in their institution and the incidence of postoperative blistering to allow for understanding of whether there was a problem with blistering in orthopaedic patients. The mean number of knee replacements was 298 (range 42–700) and the mean number of hip replacements was 305 (range 100–500). The mean proportion of wound blistering across all institutions was 15·5%, with proportions of wound blistering ranging from 1% to 55% across institutions. This clearly identified that wound blistering was a concern for the institutions involved in the Delphi.

Most commonly used wound dressing postoperatively

Considering the amount of wound dressings currently available on the market, the Delphi sought to establish which dressings were most commonly used as the first postoperative dressing. The first dressing is applied in the theatre environment by either the surgeon or their assistant. Respondents were therefore asked to identify which wound dressing would be used postoperatively on joint replacement wounds. Five respondents reported using Opsite® (Smith & Nephew, Hull, Humberside, UK) as the primary dressing. Mepilex® (Mölnlycke Health Care, Gothenburg, Sweden), Mepore® (Mölnlycke Health Care, Gothenburg, Sweden), Aquacel® (ConvaTec UK, Ickenham, Middlesex, UK) and Tegaderm® (3M UK Plc, Bracknell, Berkshire, UK) were reported as the primary dressing by one respondent each. Three respondents did not provide a response to this question.

By weighting each institution by its estimate of frequency of replacement operations, the total proportions of dressing type can be determined and are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.

Total proportions of first post operative wound dressing

| Wound dressing | Proportion of total use (%) |

|---|---|

| Mepilex® | 49.3 |

| Tegaderm® | 21.5 |

| Mepore® | 0.4 |

| Opsite® | 26.0 |

| Aquacel® | 2.8 |

Hence, Mepilex® was the most commonly used wound dressing, with its use amounting to about half of all wound dressings.

Choice of dressing during first dressing change

The first wound dressing change often occurs in the ward environment and as such the Delphi sought to establish whether the same type of wound dressing was chosen or if it was changed. Respondents were asked to identify what the choice of dressing would be for the first dressing change. Six respondents reported that when the dressing was removed for the first time postoperatively, either the same dressing or a different dressing would be applied. Four respondents reported that the same dressing would be applied. One respondent reported that a different dressing would be applied. Two respondents did not provide a response to this question.

Who should assess the wound and prescribe an appropriate wound dressing?

Wound assessment and choice of treatment tend to be the role of the nurse; however, there are occasions when this choice is medically led, and therefore investigation as to which professional group assessed the wound and prescribed the wound treatment required clarification. Eight respondents reported that the nursing staff would be most likely to first assess the patient's wound postoperatively. Two respondents reported that this could be performed by either a doctor or a member of the nursing staff. Three respondents reported that this was likely to be performed by either a doctor/surgeon or a member of the nursing staff. In all instances, where nursing staff would be most likely to prescribe the choice of wound dressing following first dressing removal, they would also be the first to assess the patient's wound postoperatively. Two respondents stated that if the wound had any signs of clinical infection then the doctor/surgeon would prescribe the first postoperative dressing. The remainder of respondents did not report whether medical staff would be involved in dressing choice, if the wound had signs of infection.

What are the consequences of wound blistering?

Respondents were presented with a range of statements relating to possible consequences of wound blistering and asked to rate their response using a Likert scale ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree. The maximum score achievable for each statement was 60, representing uniform strong agreement by all respondents. The scores achieved by all statements are summarised in Table 2.

Table 2.

Consequences of wound blistering

| Characteristic | Score |

|---|---|

| Choice of dressings is important | 56 |

| Postoperative blistering is a problem | 48 |

| Postoperative blistering leads to longer hospital stays | 46 |

| Blistering main reason for nurse to visit patient on discharge | 34 |

| Blistering leads to wound infection | 36 |

| Blistering leads to increased pain | 52 |

| Blistering associated with macerated skin | 45 |

| Blistering associated with reduced mobility | 41 |

The strongest agreement was found with the statement that choice of dressing was important. The strongest disagreement was found with the statement that blistering had been the main visit for the district nurse to visit the patient on discharge.

What are the characteristics of an ideal wound dressing?

Respondents were presented with a range of statements relating the characteristics of an ideal wound dressing. Using a Likert scale ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree, respondents were asked to identify which characteristics they thought were important. The maximum score achievable by each characteristic was 60. The scores achieved by all characteristics are summarised in Table 3.

Table 3.

Characteristics of an ideal wound dressing

| Characteristic | Score |

|---|---|

| Easy to apply | 58 |

| Conform to the patient's wound | 57 |

| Allow for swelling | 59 |

| Easy to remove | 57 |

| Be flexible | 59 |

| Pain‐free on removal | 56 |

| Not stick to the wound | 59 |

| Be transparent | 50 |

| Be able to control exudate | 54 |

| Be available as microbial | 42 |

| Be able to remain in place for 7–14 days | 48 |

| Available in variety of sizes | 58 |

| Cost‐effective | 55 |

| Supported by research | 56 |

| Available in acute and primary health care | 56 |

While the majority of characteristics were considered to be important, allow for swelling, be flexible and not stick to wound were considered the most important. Be available as an antimicrobial was considered the least important.

Second round analysis

The second round of questionnaires sought to clarify opinions from the first round. In order to assess the strength of feeling concerning the statements given in part 1, a scoring system was devised, in which ‘Agree’ was scored 1; ‘Disagree’ was scored 0 and ‘Neither agree nor disagree’ was scored 0·5. Hence, each statement could be scored out of a maximum of 9. It was found that respondents were fairly consistent in their responses to these statements, with almost all statements being scored either consistently highly or consistently poorly.

A full list of the scores of all statements is presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Results of all statements

| Nursing staff first to assess wound postoperatively * | 7.5 |

| Nursing staff should choose appropriate dressing * | 7.0 |

| Medical staff first to assess wound post‐operatively † | 2.0 |

| Medical staff should choose appropriate dressing † | 2.0 |

| Dressing removed after 24 hours and assessed † | 0.0 |

| Dressing removed after 72 hours and assessed † | 2.0 |

| Dressing left intact as long as possible * | 7.0 |

| Dressing removed on medical orders † | 0.5 |

| Postoperative blistering problem | 5.5 |

| Blistering extends hospital in‐patient stay | 6.0 |

| Blistering main reason for visit from nurse on discharge † | 0.5 |

| Blistering leads to wound infection † | 2.0 |

| Blistering leads to increased pain * | 8.0 |

| Blistering leads to macerated skin | 6.5 |

| Blistering reduces mobility | 6.0 |

*Strong agreement.

†Strong disagreement.

The highest scoring statements were as follows:

Wound blistering increases pain (score 8/9).

Registered nursing staff should be the first to assess the wound postoperatively (score 7·5/9).

The lowest scoring statements were as follows:

Wound dressing should be removed 24 hours postoperatively and the wound assessed (score 0/9).

Wound dressing should be removed only on medical orders (score 0·5/9).

Wound blistering is the main reason for a community nurse to visit a patient on discharge (score 0·5/9).

Natural groupings of statements

Within the 15 statements, some natural groupings could be found. The first four statements related to opinions on which staff should assess and choose a wound dressing. A clear preference for nursing staff, rather than medical staff, to perform these tasks was noted. Questions 5–8 elicited opinions on removal of dressing. The statement that the wound dressing should be left intact for as long as possible was clearly in line with respondents' opinions; the other three questions all scored very low. All respondents disagreed with the statement that the dressing should be removed postoperatively after 24 hours and the wound assessed. The final seven questions were concerned with the problems associated with wound blistering. Here, the strongest agreement was found with the statements that wound blistering increases pain (consistent with a similar finding from the first round of questionnaires), leads to macerated skin, extends hospital stay and reduces patient mobility.

Strong disagreement was found in the statement that blistering had been the main visit for the district nurse to visit the patient on discharge. This finding is consistent with the findings of a similarly worded statement from the first round of questionnaires.

Despite clear agreement that wound blistering causes the specific problems mentioned above, the general statement ‘Postoperative wound blistering is a problem’ was scored at only 5·5 out of 9.

Wound characteristics

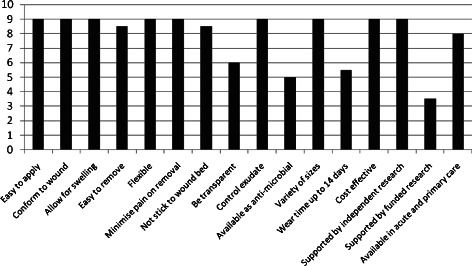

The same scoring system was devised for the wound characteristics questions, in which respondents were invited to state their agreement level with 16 statements relating to wound characteristics. The statements and level of agreement are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Summary of scores.

Many statements elicited a response of Agree from all nine respondents, and only four statements scored less than 8 out of 9.

A wound dressing should be transparent (score 6/9)

A wound dressing should be available as an antimicrobial (score 5/9)

A wound dressing should have a wear time of up to 14 days (score 5·5/9)

A wound dressing should be supported by research funded by the manufacturer (score 3·5/9)

Hence, the respondents could be said to be in broad disagreement only with this last statement. It may be seen that on the findings of this section alone, there are many statements which elicit identical levels of agreement.

Comparison of first and second rounds of questionnaires

Responses to certain questions from the second round may be compared with similarly worded set of questions on the first round of the questionnaire.

A comparison of the scores relating to the characteristics of an ideal wound dressing given in the two rounds is provided in Table 5.

Table 5.

Comparison of the scores given in the first and second rounds

| Statement | Round 1 score | Round 2 score | Round 1 % | Round 2 % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Easy to apply | 58 | 9 | 97 | 100 |

| Conform to patient's wound | 57 | 9 | 95 | 100 |

| Allow for swelling | 59 | 9 | 98 | 100 |

| Easy to remove | 57 | 8.5 | 95 | 94 |

| Flexible | 59 | 9 | 98 | 100 |

| Minimise pain on removal | 56 | 9 | 93 | 100 |

| Not stick to the wound | 59 | 8.5 | 98 | 94 |

| Transparency | 50 | 6 | 83 | 67 |

| Control exudate | 54 | 9 | 90 | 100 |

| Available as antimicrobial | 42 | 5 | 70 | 56 |

| Remain in place for 14 days | 48 | 5.5 | 80 | 61 |

| Variety of sizes | 58 | 9 | 97 | 100 |

| Cost‐effective | 55 | 9 | 92 | 100 |

| Supported by research (generic) | 56 | – | 93 | – |

| Supported by research (independent) | – | 9 | – | 100 |

| Supported by research (manufacturer) | – | 3.5 | – | 39 |

| Available in acute and primary care | 56 | 8 | 93 | 89 |

In the first round, the maximum score achievable by each statement was 60, while in the second round, the maximum score achievable by each statement was 9. Hence, for ease of comparison, percentage scores are also given in both cases. It may be seen that there are few significant changes in the levels of agreement of most statements between the two rounds of the study.

An additional score for each statement was derived as a sum of the rankings allocated to that statement by each respondent. Hence, a low score indicated a statement that respondents considered to be of greater importance. The scores obtained are summarised in Table 6.

Table 6.

Rankings allocated to each statement by respondents

| Statement | Score | Rank order |

|---|---|---|

| Easy to apply | 49.5 | 2 |

| Conform to patient's wound | 47 | 1 |

| Allow for swelling | 49.5 | 2 |

| Easy to remove | 50.5 | 4 |

| Flexible | 56 | 7 |

| Minimise pain on removal | 51 | 5 |

| Not stick to the wound | 53 | 6 |

| Transparency | 88.5 | 13 |

| Control exudate | 64.5 | 10 |

| Available as antimicrobial | 106.5 | 15 |

| Remain in place for 14 days | 60 | 9 |

| Variety of sizes | 96 | 14 |

| Cost‐effective | 58.5 | 8 |

| Supported by research (independent) | 70 | 11 |

| Supported by research (manufacturer) | 106.5 | 15 |

| Available in acute and primary care | 79 | 12 |

The responses to the second round of questionnaires showed some degree of overlap with responses to the first round. The rank ordering in this table should be interpreted with caution, as the implicit assumption that ranks from different statements are additive and may not be accurate. However, it may be tentatively stated that the first four statements in the list (easy to apply, conform to wound, allow for swelling and easy to remove), plus the statement minimise pain on removal, all of which were scored at either 9/9 or 8·5/9 on the previous section, appear to be considered the most important characteristics.

Of the questions relating to wound blistering, the majority of respondents agreed that nursing staff should be the first to assess the wound and choose the dressing, that wound dressing should be left intact for as long as possible, and that wound blistering increased pain, led to macerated skin, extended hospital stay and reduced patient mobility. In general, these findings were consistent with similar findings from the first round of questionnaires.

DISCUSSION/RECOMMENDATIONS

The English Department of Health 12, 13 clearly identified and highlighted the need for health care services to be cost‐effective and efficient ensuring that the patient is involved in all aspects of care provision, using the ethos ’no decision about me without me’ (13). This has led to increasing pressure in health care services to maintain and improve patient outcomes and reduce costs without reducing the level of quality care delivered. Harle et al.(14) identified that dressing costs represent about 0·02% of the total cost of a hip replacement operation, which may seem inexpensive unless that first dressing causes the development of a wound blister, an extended hospital in‐patient stay or extra community nurse visits to treat wound blisters. In addition to these, financial costs are the costs to patients associated with increased pain, reduced mobility, risk of infection and macerated periwound skin.

There are a wide range of wound management products available, and matching dressing selection to patient need is a major component of appropriate, clinically effective wound care(15). It is therefore essential that the professional group who assesses the patient's wound and chooses the dressing has the knowledge and skills base to be able to make an informed judgement for the planned treatment. Recommendations from the Delphi identified that nursing staff should be the first professional group to assess a wound postoperatively, and as wound care dressings account for more than £120 million in England alone each year (16); it is vital that a suitable dressing is chosen immediately. Interestingly, Fletcher (17) stated that it was widely believed that optimal care could only be successfully achieved by a multidisciplinary team; however, in reality, the majority of day‐to‐day wound care is provided by nurses. Indeed, Bianchi (18) suggested that the ultimate goal of nursing is to be clinically effective by delivering the best possible care to patients, with Timmons(19) arguing that areas that provide tissue viability specialists mean that patients are much less likely to experience poor quality wound care as good practice is promoted.

The Delphi Panel suggested that an ideal wound dressing that would help to prevent formation of wound blisters should conform easily to the wound, be easy to apply and remove, allow for swelling and minimise pain on removal. Previous authors have suggested that an ideal postoperative orthopaedic wound dressing should promote a moist environment, be absorbent, be protective, be permeable, able to remain in situ while the patient is bathing be transparent so the wound bed can be observed without the need to remove the dressing, be low adherent, act as a complete barrier to bacteria and water and be cost‐effective 3, 9, 20. Additionally, Harle et al.(14) recommended that a postoperative dressing which prevented restriction of limb movement and accommodated postoperative oedema, was particularly important in hip and knee arthroplasty patients, where postoperative swelling was common.

Results of the Delphi highlighted that the highest proportion of respondents (49·3%) stated they used Mepilex® as a primary dressing. Mepilex incorporates a Safetac® (Mölnlycke Health Care, Gothenburg, Sweden) wound contact layer, which prevents the dressing from sticking to the wound and peri wound area, thus reducing the risk of blister formation. The Delphi survey showed OpSite Post‐Op as the second most popular choice of dressing (26% of respondents). This dressing was compared with a standard absorbent dressing in a clinical audit undertaken by Bhattacharyya et al.(21) in which no OpSite Post‐Op patients experienced a tape blister, signs of inflammation at suture removal or wound infection. Therefore, it would appear that the majority of respondents were choosing dressings that had evidence to support their use in preventing damage to the skin.

Delphi participants were in agreement that the primary wound dressing should be left in situ for as long as possible, providing there was no excessive oozing or signs of infection. This is supported by Leaper(22) who stated that frequent dressing changes can be a potential risk factor for infection as bacteria may contaminate the wound during the procedure.

CONCLUSIONS

The majority of respondents stated that nursing staff should be the first to assess a wound postoperatively and to choose the appropriate wound dressing. The majority of respondents agreed that the wound dressing should be left intact for as long as possible and that pain was the main consequence of wound blistering.

Respondents strongly agreed that postoperative wound blistering could lead to increased pain, macerated skin, lead to wound infection; reduce mobility and increase a length of stay as an in‐patient. They did not rate strongly that wound blistering was the main reason for a district nurse to visit patients on discharge home; perhaps, this was because patients remained in hospital for a longer period of time to allow for the blister to heal. The most important factor in preventing a wound blister was the choice of postoperative wound dressing.

SUMMARY

Respondents of this Delphi survey agreed that the top five ideal constituents of a wound dressing to prevent the formation of a blister were as follows:

-

1

Ability to conform to the wound

-

2

Easy to apply

-

3

Allow for swelling

-

4

Easy to remove

-

5

Minimise pain on removal

The five lowest ranked constituents of a wound dressing by the Delphi Panel were as follows:

-

1

Supported by research (independent)

-

2

Supported by research (manufacturer)

-

3

Transparent

-

4

Available as antimicrobial

-

5

Available in acute and primary care

Although the ERG was relatively compact, this study arguably provides some useful data that can be used to identify the consequences of wound blistering and the important factors that need to be considered when choosing a wound dressing to prevent blistering.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank all members of the Delphi survey panel who contributed their time to completing the questionnaires. This project was supported by an unrestricted educational grant from Mölnlycke Health Care to enable the researchers to undertake the Delphi survey. Mölnlycke Health Care read the manuscript prior to submission.

References

- 1. Tustanowski J. Effect of dressing choice on outcomes after hip and knee arthroplasty: a literature review. J Wound Care 2009;18:449–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wright M. Hip blisters. Nurs Times 1994;90:86–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cosker T, Elsayed S, Gupta S, Mendonca AD, Tayton KJJ. Choice of dressing has a major impact on blistering and healing outcomes in orthopaedic patients. J Wound Care 2005;14:27–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gupta SK, Lee S, Moseley LG. Postoperative wound blistering: is there a link with dressing usage?. J Wound Care 2002;11:271–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Collins A. Does the postoperative dressing regime affect wound healing after hip or knee arthroplasty?. J Wound Care 2011;20:11–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Clarke JV, Deakin AH, Dillon JM, Kinninmonth AWG. A prospective clinical audit of a new dressing design for lower limb arthroplasty wounds. J Wound Care 2009;18:5–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Polatsch DB, Baskies MA, Hommen JP, Egol KA, Koval KJ. Tape blisters that develop after hip fracture surgery: a retrospective series and a review of the literature. Am J Orthop 2004;33: 452–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jester R, Russell L, Fell S, Williams S, Prest C. A one hospital study of the effect of wound dressings and other related factors on skin blistering following total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Orthop Nurs 2000;4:71–7. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bhattacharyya M. A prospective clinical audit of patient dressing choice for post operative arthroscopy wounds. Wounds UK 1988;96:189–91. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Blaylock B. Tape injury in the patient with total hip replacement. Orthop Nurs 1995;14:25–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schmitz M. Evaluation of a hydrocolloid dressing. J Wound Care 1996;9:396–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Department of Health 2009: NHS2010–2015. From good to great Available at URL www.doh.gov.uk/stats/pca99.htm [accessed on 6 July 2011]

- 13. Department of Health. Equity and excellence: liberating the NHS. London: The Stationery Office, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Harle S, Korhonen A, Kettunen J, Seitsalo S. A randomised clinical trial of two different wound dressing materials for hip replacement patients. Orthop Nurs 2005;9:205–10. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Smith G, Greenwood M, Searle R. Ward nurses' use of wound dressings before and after a bespoke education programme. J Wound Care 2009;19:396–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. National Prescribing Centre. Evidence based prescribing of advanced wound dressings for chronic wounds in primary care. MeRec Bulletin 2010;21:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fletcher J. Optimising Wound Care in the UK and Ireland: a best practice statement. Wounds UK 2008;4:73–1. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bianchi J. A review of leg ulcer modules at four UK universities. Wounds UK 2007;3:100–4. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Timmons J. Good research is essential in these fast moving times. Wounds UK 2007;3:8. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Aindow D, Butcher M. Films or fabrics: is it time to re‐appraise postoperative dressings?. Br J Nurs 2005;14:S15–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bhattacharyya M, Bradley H, Holder S, Gerber B. A prospective clinical audit of patient dressing choice for post‐op arthroscopy wounds. Wounds UK 2005;1:30–4. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Leaper DJ. Wound infection. In: Russell RCE, Norman S, Christopher W, Bulstrade JG, editors. Bailey and Love's Short Practice of Surgery, 24th edn. London: Hodder Arnold,2000:87–98. [Google Scholar]