Abstract

Chronic venous ulceration (CVU) is the major cause of chronic wounds of lower extremities, and is a part of the complex of chronic venous disease. Previous studies have hypothesised that several thrombophilic factors, such as hyperhomocysteinaemia (HHcy), may be associated with chronic venous ulcers. In this study, we evaluated the prevalence of HHcy in patients with venous leg ulcers and the effect of folic acid therapy on wound healing.

Eighty‐seven patients with venous leg ulcers were enrolled in this study to calculate the prevalence of HHcy in this population. All patients underwent basic treatment for venous ulcer (compression therapy ± surgical procedures).

Patients with HHcy (group A) received basic treatment and administered folic acid (1·2 mg/day for 12 months) and patients without HHcy (group B) received only basic treatment. Healing was assessed by means of computerised planimetry analysis.

The prevalence of HHcy among patients with chronic venous ulcer enrolled in this study was 62·06%. Healing rate was significantly higher (P < 0·05) in group A patients (78·75%) compared with group B patients (63·33%).

This study suggests a close association, statistically significant, between HHcy and CVU. Homocysteine‐lowering therapy with folic acid seems to expedite wound healing. Despite these aspects, the exact molecular mechanisms between homocysteine and CVU have not been clearly defined and further studies are needed.

Keywords: Chronic venous disease, Chronic venous ulceration, Hyperhomocysteinaemia, Thrombophilia, Venous leg ulcer

Introduction

Chronic venous disease (CVD), widespread in western countries (up to 57% in males and 77% in females), is associated with chronic leg ulcerations ranging up to 2% in the general population. Chronic venous ulceration (CVU) represents a chronic or recurrent manifestation with both higher economic costs and psychological impact 1, 2, 3, 4. Several patients with CVD do not develop skin ulcerations; therefore, probably other factors may be involved in the pathogenesis of venous ulcers 5. Previously, it has been hypothesised that thrombophilia predisposes to the development of superficial and deep lower limb reflux with the occurrence of CVU 6. Patients with CVU have shown at least one thrombophilic disorder such as hyperhomocysteinaemia(HHcy) 7.

HHcy represents both a reaction to acute illness and an important risk factor for cardiovascular mortality in patients with a history of myocardial infarction, stroke, angina pectoris, diabetes or hypertension 8, 9, 10.

Previously, it was reported that several factors (e.g. lifestyle, diseases, diet, drugs and polymorphisms in genes encoding enzymes or proteins involved in Hcy metabolism) could be able to influence plasma Hcy levels 11, 12, and it has been also documented a direct correlation between plasma Hcy levels and folic acid 13.

In this study, we evaluated the prevalence of HHcy in patients with CVU and the effects of folic acid on wound healing.

Methods

Study design

Patients with sign and symptoms of CVU were recruited into an open label, parallel‐group, single‐centre study between January 2008 and December 2010. This study was approved by the Researchers Ethics Committee and was conducted in agreement with the Declaration of Helsinki and the Guideline for Good Clinical Practice. All participants signed a written informed consent prior to enrolment.

Population

Patients eligible for the study were of both sexes, older than 18 years and with CVU diagnosed according to Clinical CEAP classification class 6 (C6) 14.

All patients underwent duplex ultrasound examination of lower limbs. Both the deep and superficial veins were assessed for patency and the presence of reverse flow (Table 1) as well as the measurement of ankle‐brachial index in order to exclude the presence of peripheral artery disease.

Table 1.

Baseline patients characteristics

| Features | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Number of patients | 87 |

| Sex (M/F) Males Females |

26 (29·88%) 61 (70·11%) |

| Age

Age range Median age |

46–87 67 |

| Duplex ultrasound findings Superficial vein incompetence Perforating vein incompetence Superficial + perforating incompetence Deep vein incompetence/obstruction |

81 (93·10%) 4 (4·59%) 3 (3·44%) 0 |

| Surgery Superficial vein surgery SEPS Superficial vein surgery + SEPS |

77 (95·06%) 2 (100%) 3 (100%) |

| Concomitant conditions Arterial hypertension Obesity |

37 (42·52%) 19 (21·83%) |

| Ulcer features Ulcer area (range) Ulcer area (mean) |

3·2–20·7 cm2 14·8 cm2 |

SEPS, subfascial endoscopic perforator surgery.

Patients who met the following conditions were excluded: known condition related to a congenital and/or acquired thrombophilic defects and medical aetiologies for HHcy such as known blood clotting disorders, peripheral arterial disease (ankle‐brachial index ≤ 0·9), previous thromboembolism, history of malignancy, connective tissue disorders, inflammatory bowel disease, surgery ≤ 3 months, pregnancy – current or ≤6 months, hypothyroidism, known hepatic or renalinsufficiency, oestrogen replacement therapy, psoriasis, consumption of tobacco or abuse drugs.

Homocysteine plasma levels

At the time of admission, a blood sample was drawn from each enrolled patient in order to determine plasma Hcy levels. The samples were centrifuged and plasma Hcy levels were evaluated in agreement with other previous study 13.

HHcy was defined in the presence of plasma Hcy level greater than 15 µmol/l. Mild–moderate HHcy was considered for levels of Hcy up to 30 µmol/l, intermediate HHcy was considered for levels up to 100 µmol/l and severe HHcy was considered for levels greater than 100 µmol/l 15, 16.

Experimental protocol

Enrolled patients were subjected to the most appropriate treatment considering the patient's wishes. The type of surgery, when it was accepted, was chosen according to anatomical level of vein incompetence: superficial venous surgery (CHIVA procedure is the procedure of choice at our institutions in these cases) and/or subfascial endoscopic perforating surgery (Table 1).

The enrolled patients were divided into two groups:

Group A: CVU patients with HHcy treated with folic acid (1·2 mg/day) + basic treatment for 12 months.

Group B: CVU patients without HHcy treated only with basic treatment.

Basic treatment consists of a treatment with third‐class medical compression stocking (36–50 mmHg) for 12 months and then with second‐class medical compression stocking (25–40 mmHg) for the remaining 24 months. The median follow‐up was 14 months (weekly office visit).

Healing

Healing was assessed through direct ulcer tracing onto clear plastic sheet and subsequent computerised planimetry. It was calculated using the following formula:

where IUA is the initial ulcer area expressed in centimetre, FUA is the final ulcer area expressed in centimetre and NW is the number of weeks that the patient had been observed to obtain the total area healed per week.

Endpoints

The primary endpoint was the correlation between HHcy and CVU. A co‐endpoint included the effects of folic acid on the healing of the ulcer. The overall clinical response during the study was assessed by physicians who were blinded to the treatment.

Sample size

In agreement with statistical input, data indicate that the difference in the response of matched pairs is normally distributed with standard deviation 3·2. If the true difference in the mean response of matched pairs is 2, we need to study 29 pairs of subjects to be able to reject the null hypothesis that this response difference is zero with probability (power) 090. The type I error (alpha) probability associated with this test of this null hypothesis is 0·05.

Statistical analysis

The analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was used to analyse differences in efficacy measures for the primary efficiency endpoint. Also, the paired t‐test was used for the change in efficacy measures within each group. Comparison of health status between the groups was assessed by either ANOVA or Student–Newman–Keuls test. For all comparisons, differences were considered significant for P < 0·05. SPSS (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) and G*Power (Institut fur Experimentelle Psychologie, Heinrich Heine Universitat, Dusseldorf, Germany) software were used for the statistical analyses.

Results

Patient population

During the study period, 87 patients with CVU [26 males (26·43%) and 61 females (70·11%), age range 46–87 years and median age 67 years] (CEAP clinical grade 6) 16 were recruited. Full demographics of patient population are shown in Table 1.

Plasma Hcy levels

The prevalence of HHcy, at admission, among the enrolled CVU patients was 62·06%. In particular, we enrolled 54 patients (17 males and 37 females) in group A (HHcy) and 33 patients (9 males and 24 females) in group B (without HHcy). Demographic characteristics of each group are shown in Table 2.The median follow‐up was 2·7 years.

Table 2.

Groups characteristics

| Features | Group A | Group B |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 54 | 33 |

| Sex (M/F) Males Females |

17 (31·48%) 37 (68·51%) |

9 (27·27%) 24 (72·73%) |

| Age Age range Median age |

49–87 67 |

46–83 67 |

| Duplex ultrasound findings Superficial vein incompetence Perforating vein incompetence Superficial + perforating incompetence |

49 (90·74%) 3 (5·55%) 3 (5·55%) |

32 (96·97%) 1 (3·03%) 0 |

| Surgery Superficial vein surgery SEPS Superficial vein surgery + SEPS |

47 (95·91%) 3 (100%) 3 (100%) |

30 (90·90%) 1 (100%) |

| Concomitant conditions Arterial hypertension Obesity |

25 (46·30%) 11 (20·37%) |

12 (36·37%) 8 (24·24%) |

| Ulcer features Ulcer area (range) Ulcer area (mean) |

3·2–18·5 cm2 13·7 cm2 |

3·6–20·7 cm2 15·9 cm2 |

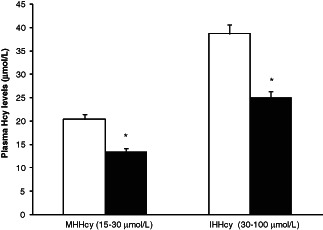

In group A, we documented that 39 patients (10 males and 29 females) presented moderate HHcy (mean 21·4 µmol/l and SD 4·5), while 15 patients (7 males and 8 females) presented intermediate HHcy (mean 38·7 µmol/l and SD 11·7) and no severe HHcy was recorded in this study (Figure 1). The treatment with folic acid induced a significant decrease of plasma Hcy levels (P < 0·01) in both moderate and intermediate HHcy levels (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Plasma homocysteine levels in group A patients at the time of the enrolment (white column) and after the treatment (dark column). The values are expressed as mean ± SEM.*P < 0·01 treatment versus the enrolment.

Seven patients in group A (12·96%; two with moderate HHcy and five with intermediate HHcy) and three in group B (9·09%) were lost during the follow‐up in the first 2 months after the beginning of the study. The remaining patients completed the study (47 of group A and 30 of group B) receiving the treatment in agreement with the experimental protocol previously described.

Healing

Healing rate at 12 months was significantly higher in group A treated with folic acid (78·72%) with respect to group B (63·33%) (P < 0·05). The mean total ulcer area rate of healing was 1·1 cm2/week for group A and 0·92 cm2/week for group B (P < 0·05) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Healing rates at 12 months

| Group A | Group B | |

|---|---|---|

| Healed ulcers Mean area healed per week (cm2/week) |

37 (78·72%) 1·1 |

19 (63·33%) 0·92 |

| Non healing ulcers | 10 (21·28%) | 11 (36·66%) |

Recurrence rate

During the study, recurrence rate was recorded in one male and in one female of group A (5·40%) and in one female of group B (5·26%), 14th, 20th and 17th months, respectively, after the beginning of the study.

Discussion

In this study, we documented an involvement of HHcy in CVU. Previously, it has been documented an association between HHcy and CVU 7.

In our study, 62·06% of patients with CVU had mild–moderate to intermediate HHcy with plasma levels ranging from 15 to 50 µmol/l.

It is estimated that 5–7% of the general population has mild to intermediate HHcy, which represents an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease. HHcy seems to contribute to the development of endothelial dysfunction by the induction of pro‐inflammatory factors and oxidative stress 17. Moreover, HHcy may cause downregulation of lysyl oxidase, an enzyme involved in extracellular matrix (ECM) maturation, promoting in this way the alteration of ECM composition 18, and this may also contribute to the pathological changes observed in CVU. HHcy has additional effects on vascular smooth muscle such as it may increase the secretion of metalloproteinases that may cause the alteration of degradation and remodelling of ECM 19.

HHcy is also clearly associated with an increase of thrombotic risk and both microvascular thrombosis and pericapillary fibrin cuff formation, affecting vascular interstitium and ECM, may play a role in the pathogenesis of CVU 20.

Moreover, in an experimental study in mice, Jacovina et al. 21 showed that Hcy blocking the annexin A2 complex (a fibrinolytic agent) prevents perivascular fibrinolysis and inhibits directed endothelial cell inducing microvascular dysfunction. This mechanism may reflect both the impairment of microvascular thromboresistance and the inhibition of microvascular remodelling present in wound healing.

On the arterial side, the linear relationship between plasma Hcy and cardiovascular disease risk stimulated several attempts on HHcy‐lowering therapy in order to improve vascular disease‐associated morbidity and mortality 22, 23. Moreover, HHcy increases free radical formation and enhances inflammation 11 and this may be related with the progression of the ulcer.

The effect of folic acid on Hcy has been previously reported, suggesting that a decrease in folate, vitamin B12 and vitamin B6 could induce a significant increase in plasma Hcy levels 10.

In this light, in our study, we documented that the administration of folic acid is able to reduce the plasma Hcy levels and improve the healing of the ulcer. However, it is important to underline that genetic factors may also be related with the plasma HHcy levels, that is, mutations in methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) gene or in cystathionine β‐synthase (CBS), both involved in Hcy metabolism. In this article, we have not evaluated the impact of these mutations on plasma HHcy levels and this could represent a limit of this study.

Nevertheless, this study suggests that HHcy may represent a marker of CVU and that HHcy‐lowering therapy may play a role in expediting wound healing, even if further studies are necessary to confirm our analysis.

Author contribution

SdF and RS were responsible for conception and design, critical revision, and had given final approval of the version to be published. GD and LG were responsible for interpretation of data, drafting the manuscript, and had given final approval of the version to be published. PL, GB, VM and SDM were responsible for acquisition of data, drafting the manuscript, and had given final approval of the version to be published.

Acknowledgement

This study received no funding. The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1. Serra R, Buffone G, de Franciscis A, Mastrangelo D, Vitagliano T, Greco M, de Franciscis S. Skin grafting followed by low‐molecular‐weight heparin long‐term therapy in chronic venous leg ulcers. Ann Vasc Surg 2012;26:190–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Reichenberg J, Davis M. Venous ulcers. Semin Cutan Med Surg 2005;24:216–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Serra R, Buffone G, de Franciscis A, Mastrangelo D, Molinari V, Montemurro R, de Franciscis S. A genetic study of chronic venous insufficiency. Ann Vasc Surg 2012;26:636–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Serra R, Buffone G, Costanzo G, Montemurro R, Perri P, Damiano R, de Franciscis S. Varicocele in younger as risk factor for inguinal hernia and for chronic venous disease in older: preliminary results of a prospective cohort study. Ann Vasc Surg 2012. in press. DOI: 10.1016/j.avsg.2012.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Serra R, Buffone G, Falcone D, Molinari V, Scaramuzzino M, Gallelli L, de Franciscis S. Chronic venous leg ulcers are associated with high levels of metalloproteinases‐9 and neutrophil gelatinase associated lipocalin. Wound Repair Regen 2012. in press. DOI: 10.1111/wrr12035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Darvall KA, Sam RC, Adam DJ, Silverman SH, Fegan CD, Bradbury AW. Higher prevalence of thrombophilia in patients with varicose veins and venous ulcers than controls. J Vasc Surg 2009;49:1235–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sam RC, Burns PJ, Hobbs SD, Marshall T, Wilmink AB, Silverman SH, Bradbury AW. The prevalence of hyperhomocysteinemia, methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase C677T mutation, and vitamin B12 and folate deficiency in patients with chronic venous insufficiency. J Vasc Surg 2003;38:904–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. De Bree A, Verschuren WM, Kromhout D, Kluijtmans LA, Blom HJ. Homocysteine determinants and the evidence to what extent homocysteine determines the risk of coronary heart disease. Pharmacol Rev 2002;54:599–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Boysen G, Brander T, Christensen H, Gideon R, Truelsen T. Homocysteine and risk of recurrent stroke. Stroke 2003;34:1258–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vollset SE, Refsum H, Tverdal A, Nygård O, Nordrehaug JE, Tell GS, Ueland PM. Plasma total homocysteine and cardiovascular and noncardiovascular mortality: the Hordalans Homocysteine study. Am J Clin Nutr 2001;74:130–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Siniscalchi A, Mancuso F, Gallelli L, Ferreri Ibbadu G, Biagio Mercuri N, De Sarro G. Increase in plasma homocysteine levels induced by drug treatments in neurologic patients. Pharmacol Res 2005;52:367–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Siniscalchi A, Gallelli L, Mercuri NB, Ibbadu GF, De Sarro G. Role of lifestyle factors on plasma homocysteine levels in Parkinson's disease patients treated with levodopa. Nutr Neurosci 2006;9:11–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Siniscalchi A, De Sarro G, Loizzo S, Gallelli L. High plasma homocysteine and low serum folate levels induced by antiepileptic drugs in Down syndrome. JoDD 2012;18:70–6. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Eklöf B, Rutherford RB, Bergan JJ, Carpentier PH, Gloviczki P, Kistner RL, Meissner MH, Moneta GL, Myers K, Padberg FT, Perrin M, Ruckley CV, Smith PC, Wakefield TW. Revision of the CEAP classification for chronic venous disorders: consensus statement. J Vasc Surg 2004;40:1248–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. De Luca G, Suryapranata H, Gregorio G, Lange H, Chiariello M. Homocysteine and its effects on in‐stent restenosis. Circulation 2005;112:e307–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Melhem A, Desai A, Hofmann MA. Acute myocardial infarction and pulmonary embolism in a young man with pernicious anemia‐induced severe hyperhomocysteinemia. Thromb J 2009;7:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lawrence de Koning AB, Werstuck GH, Zhou J, Austin RC. Hyperhomocysteinemia and its role in the development of atherosclerosis. Clin Biochem 2003;36:431–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Raposo B, Rodríguez C, Martínez‐González J, Badimon L. High levels of homocysteine inhibit lysyl oxidase (LOX) and downregulate LOX expression in vascular endothelial cells. Atherosclerosis 2004;177:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schwartzfarb EM, Romanelli P. Hyperhomocysteinemia and lower extremity wounds. Int J Low Extrem Wounds 2008;7:126–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bradbury AW, MacKenzie RK, Burns P, Fegan C. Thrombophilia and chronic venous ulceration. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2002;24:97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jacovina AT, Deora AB, Ling Q, Broekman MJ, Almeida D, Greenberg CB, Marcus AJ, Smith JD, Hajjar KA. Homocysteine inhibits neoangiogenesis in mice through blockade of annexin A2‐dependent fibrinolysis. J Clin Invest 2009;119:3384–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Maron BA, Loscalzo J. The treatment of hyperhomocysteinemia. Annu Rev Med 2009;60:39–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lee M, Hong KS, Chang SC, Saver JL. Efficacy of homocysteine‐lowering therapy with folic Acid in stroke prevention: a meta‐analysis. Stroke 2010;41:1205–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]