Abstract

Chronic wounds represent a major socio‐economic problem in developed countries today. Wound healing is a complex biological process. It requires a well‐orchestrated interaction of mediators, resident cells and infiltrating cells. In this context, mesenchymal stem cells and keratinocytes play a crucial role in tissue regeneration. In chronic wounds these processes are disturbed and cell viability is reduced. Hydroxyectoine (HyEc) is a membrane protecting osmolyte with protein and macromolecule stabilising properties. Adipose‐derived stem cells (ASC) and keratinocytes were cultured with chronic wound fluid (CWF) and treated with HyEc. Proliferation was investigated using MTT test and migration was examined with transwell‐migration assay and scratch assay. Gene expression changes of basic fibroblast growth factor (b‐FGF), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), matrix metalloproteinases‐2 (MMP‐2) and MMP‐9 were analysed by quantitative real‐time polymerase chain reaction (qRT‐PCR). CWF significantly inhibited proliferation and migration of keratinocytes. Addition of HyEc did not affect these results. Proliferation capacity of ASC was not influenced by CWF whereas migration was significantly enhanced. HyEc significantly reduced ASC migration. Expression of b‐FGF, VEGF, MMP‐2 and MMP‐9 in ASC, and b‐FGF, VEGF and MMP‐9 in keratinocytes was strongly induced by chronic wound fluid. HyEc enhanced CWF induced gene expression of VEGF in ASC and MMP‐9 in keratinocytes. CWF negatively impaired keratinocyte function, which was not influenced by HyEc. ASC migration was stimulated by CWF, whereas HyEc significantly inhibited migration of ASC. CWF induced gene expression of VEGF in ASC and MMP‐9 in keratinocytes was enhanced by HyEc, which might partly be explained by an RNA stabilising effect of HyEc.

Keywords: Adipose‐derived stem cells, Chronic wound, Gene expression, Hydroxyectoine, Keratinocytes, Migration, Proliferation, Wound fluid, Wound healing

Introduction

As a result of an ageing population with increasing morbidity, the incidence of chronic wounds is constantly rising. This evolution pictures a major socio‐economic problem in developed countries with growing costs in health care systems 1. Physiological wound healing is a complex biological process proceeding from inflammation through proliferation to maturation 2. It requires a well‐orchestrated interaction of mediators, resident cells and infiltrating cells. Basal keratinocytes and fibroblasts play an important role in this process as they proliferate and migrate and finally lead to a complete wound closure. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) promote the regeneration process as they have the ability to stimulate contributing cells via paracrine mechanisms and replace damaged tissue 3.

In chronic wounds these physiological processes are disturbed by mediators of the wound environment. Chronic wound fluid (CWF) is characterised by elevated local levels of pro‐inflammatory cytokines such as tumour necrosis factor‐α (TNF‐α) and interleukin‐1 (IL‐1) compared with acute wound fluid (AWF). Proteases like matrix metalloproteinases (MMP) and neutrophil elastase are also elevated whereas levels of tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMP) are reduced 4, 5, 6. MMP‐2 and MMP‐9 are involved in the degradation of extracellular matrix and therefore play a key role in wound healing, both during remodelling and reepithelialisation 7. The content of growth factors in CWF was reported to be significantly lower than in AWF 8, 9. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and basic fibroblast growth factor (b‐FGF) are two pivotal cytokines in wound healing processes 10, 11. VEGF stimulates angiogenesis via the HIF‐1α pathway induced by hypoxia 12, whereas b‐FGF has positive effects on proliferation, migration and angiogenic processes 13, 14.

It has been shown that adipose‐derived stem cells (ASC) can positively influence wound healing 15. They are attracted to the wound site and stimulate wound healing processes via paracrine mechanisms as well as fusion and differentiation, for example into keratinocytes or fibroblasts 16. They are able to promote reepithelialisation and angiogenesis and thereby accelerate wound healing 17. However, undisturbed cell function is an essential requirement for regenerative processes.

Several authors reported that CWF inhibits proliferation and viability of human fibroblasts and keratinocytes. These effects are mainly explained by the imbalance of growth factors and proteases 5, 18, but oxidative stress appears to be another cause for tissue damage in chronic wounds 19. Lipid peroxidation caused by reactive oxygen species (ROS) leads to a degradation of membrane lipids followed by cell damage.

Hydroxyectoine [(S,S)‐2‐methyl‐5‐hydroxy‐1,4,5,6‐tetrahydropyrimidin‐4‐carboxylacid] is a hydroxylated ectoine derivate, and was first detected in the Gram‐positive soil bacterium Streptomyces parvulus 20. It is a zwitterionic, low‐molecular weight and strong water‐binding organic molecule and belongs to the class of compatible solutes. It is synthesised and enriched within the bacteria during environmental stress conditions like high temperature, freezing, extreme dryness and high salinity 21. Interestingly, compatible solutes are biologically inert and do not interfere with the overall cellular functions. Because they protect cell membranes against different types of stress 22, we hypothesised that treatment of impaired ASC and keratinocytes with hydroxyectoine (HyEc) may improve cell viability and therefore positively influence the wound healing.

Materials and methods

For collection of ASC and CWF, approval was given by the ethics committee of the University of Witten/Herdecke (39/2007). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients for sample collection.

Keratinocytes

HaCaT (human adult low calcium high temperature) cells, an immortalised human keratinocyte cell line developed by Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum Heidelberg (DKFZ), were purchased from Cell Lines Service (CLS, Eppelheim, Germany). They were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM; Biochrom, Berlin, Germany) containing 10% foetal calf serum (FCS) or 2% FCS in experimental settings. HaCaT were used between passages 45 and 54.

Adipose‐derived stem cells

ASC were isolated from lipoaspirate after abdominal liposuction. Liposuction was performed using the tumescence technique. The fat fraction of the sample was homogenised using collagenase I (Sigma‐Aldrich, Munich, Germany) and ASC were isolated by centrifugation. ASC were cultured in α‐MEM (PAN Biotech, Aidenbach, Germany) containing 20% FCS (Sigma‐Aldrich), 1 ng/ml b‐FGF, 1 ng/ml EGF and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. For further experiments they were cultured in DMEM containing 2% FCS (Sigma, Hamburg, Germany) and 2% kanamycine. ASC were used in passages 2 and 3.

Identification of ASC

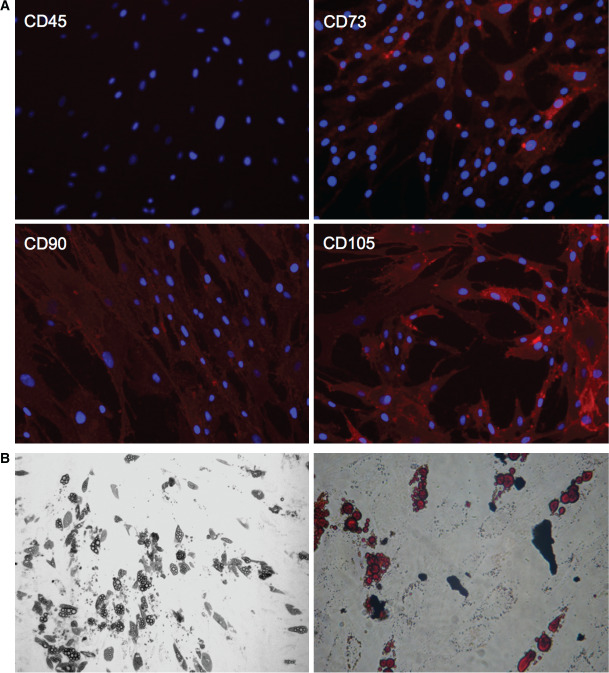

ASC were identified as human MSC according to the minimal criteria of the International Society for Cellular Therapy: plastic‐adherence, expression of CD73, CD90 and CD105, lack of CD45 expression and the ability to differentiate into adipocytes 23.

For immunophenotyping, ASC were cultured as described above. After 2 days they were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Immunofluorescence staining was performed using anti‐human CD45, CD90 and CD105 primary antibodies (Stemgent, San Diego, CA) and an Alexa Fluor 568 coupled secondary antibody (Stemgent). A phycoerythrin (PE) conjugated anti‐human CD73 antibody (BioLegend, Fell, Germany) was used for CD73 staining and a PE coupled IgG antibody (BioLegend) served as isotype control. Nuclei were stained with bisBenzimide (Sigma). Fluorescence microscopy was carried out using the fluorescence microscope Leica CTR400 (Wetzlar, Germany).

To prove adipogenesis, ASC were cultured in human NH AdipoDiff Medium (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch‐Gladbach, Germany). After 3 weeks they were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with Oil‐Red‐O (Sigma). Microscopic analysis was performed for evidence of fat differentiation.

Preparation of chronic wound fluid

CWF was harvested from patients suffering from a third degree chronic sacral decubitus ulcer. All full thickness wounds existed for at least 6 weeks. Patients with previous vacuum therapy or any type of surgery were excluded. Wound fluid was collected by applying an occlusive dressing for 24 hours. After centrifugation the supernatant was diluted with DMEM and passed through a sterile filter. Wound fluids from five patients were subjected to Bradford assay for protein quantification and pooled for further experiments.

To evaluate the most suitable wound fluid concentration, we investigated different concentrations of CWF with respect to their impact on ASC and keratinocyte proliferation using MTT assay. On the basis of these results we chose a concentration of 2% CWF. HyEc was added to the medium using three different concentrations: 1 mM, 100 μM and 10 μM. In all experiments, cell cultures were incubated with HyEc alone, CWF alone and CWF plus HyEc. For scratch assays after sole incubation with HyEc, only the most effective concentration was applied together with CWF. For quantitative real‐time polymerase chain reaction (qRT‐PCR) the most effective HyEc concentration resulting from proliferation and migration assays was used.

Proliferation assay (MTT)

MTT test was performed to examine cell proliferation. Therefore ASC and keratinocytes were seeded on 96‐well microplates. After 12 hours, when cells attached to the wellplate, incubation with HyEc, CWF or CWF and HyEc was performed. MTT assay was realised after 24 and 48 hours, using MTT reagent (5 µg/ml; Sigma‐Aldrich, Hamburg, Germany) according to the manufacturers' instructions. Excitation was measured at 570 nm using the ELISA (enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay) reader μQuant (Biotek, Bad Friedrichshall, Germany).

Transwell‐migration assay

ASC were cultured as described above. Cell culture inserts (FalconTM FluoroBlok™, pore size 8 µm; BD Bioscience, Heidelberg, Germany) were placed in a 24‐well microplate; 10 000 ASC were seeded into the upper chamber. After 4 hours CWF, HyEc or CWF and HyEc were added to the bottom chamber, with standard culture medium serving as a control. Following 24 hours of incubation, membranes were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) and stained with 4′,6‐diamidino‐2‐phenylindole (DAPI; Sigma‐Aldrich). Migrated and non‐migrated cells were counted in eight randomly selected high‐power fields at 400× magnification using the fluorescence microscope Leica CTR400 and Leica Application Suite V3·6 software.

Scratch assay

Keratinocytes were cultured in six‐well microplates at a density of 700 000 cells per well. After 24 hours, cells were incubated with 10 µg/ml mitomycin C (Serva, Heidelberg, Germany) for 2 hours to disable cell proliferation. The keratinocyte monolayer was then scratched with a plastic pipette tip in a standardised manner. Culture medium was replaced with medium containing CWF, HyEc or CWF plus HyEc. In vitro reepithelialisation was documented by photography using Leica CTR400 microscope and Leica Application Suite V3·6 software. Wound closure was evaluated measuring the remaining cell‐free area using Adobe Photoshop 12·0 and expressed as percentage of the initial cell‐free zone.

Quantitative real‐time PCR

A total of 250 000 ASC and 400 000 keratinocytes were placed on six‐well microplates and cultured according to standard protocols. After 24 hours they were exposed to CWF, HyEc or CWF and HyEc for 6 hours or left untreated. Cells were dissolved in RLT buffer and RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturers' instructions. cDNA synthesis of 1 µg total RNA was performed with the RevertAid First Strand cDNA synthesis Kit (Fermentas, St. Leon‐Rot, Germany). qRT‐PCR was performed using the Brilliant II SYBR Green QRT‐PCR Master Mix (Agilent Technologies, Böblingen, Germany). Data were acquired with Stratagene Mx3005P QPCR System (Agilent Technologies). Primers were obtained from Biomers (Ulm, Germany; Table S1, Supporting information). Expression was normalised to the housekeeping gene RPL. The comparative threshold cycle (CT) method was applied to determine relative expression differences 24.

Statistical analysis

To achieve statistical significance, all experiments were performed in at least three independent approaches. The results were assessed by Student's t‐test and are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). A P value of <0·05 was considered significant.

Results

ASC were shown to be positive for cell surface marker CD73, CD90 and CD105 and negative for CD45 (Figure 1A). They presented plastic‐adherence in standard cell culture. Oil‐Red‐O staining after cultivation with AdipoDiff medium showed differentiation into adipocytes with their typical fat vacuoles (Figure 1B). Therefore ASC were characterised as human MSC according to the minimal criteria of the International Society for Cellular Therapy 23.

Figure 1.

(A) Expression of cell surface marker by adipose‐derived stem cells (ASC). Detection of CD73, CD90 and CD105 expression and lacking CD45 expression. (B) Adipogenesis of ASC. Pictures show intracellular lipid droplets under phase contrast microscopy (left side) and after Oil‐Red‐O staining (right side).

Protein concentrations of CWF obtained from five patients ranged from 28·64 g/l to 38·25 g/l (33·45 ± 6·80 g/l) as summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.

Protein concentrations of chronic wound fluid (CWF)

| Sample | Protein concentration (g/l) |

|---|---|

| CWF I | 31·34 |

| CWF II | 35·81 |

| CWF III | 34·3 |

| CWF IV | 32·26 |

| CWF V | 38·25 |

| Mean ± SD | 33·45 ± 6·80 |

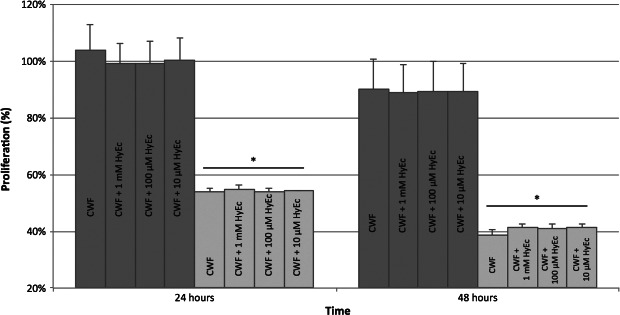

Proliferation of ASC and keratinocytes

ASC proliferation was not significantly affected by CWF; 24 hours following incubation proliferation capacity slightly increased to 103·66% and decreased after 48 hours to 89·93%. Proliferation of keratinocytes was negatively influenced by CWF. After 24 hours, proliferation reduced to 53·95% and further decreased to 38·64% after 48 hours (both P < 0·001). Addition of different concentrations of HyEc did not alter these results. Details are presented in Figure 2. Sole incubation with HyEc had no effect on proliferation rates of ASC and keratinocytes.

Figure 2.

Proliferation of adipose‐derived stem cells (ASC, dark grey bars) and keratinocytes (light grey bars) after incubation with chronic wound fluid (CWF) and addition of hydroxyectoine (HyEc) in different concentrations, presented as percentage related to the untreated control. Shown are the results of five independent experiments plotted as mean + SEM. Keratinocyte proliferation significantly decreased after 24 and 48 hours (* P < 0·001), whereas proliferation of ASC did not significantly change. HyEc did not change these results in none of the tested concentrations.

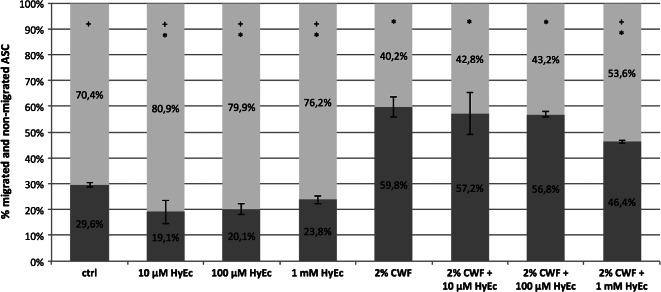

Transwell‐migration of ASC

ASC were attracted to CWF, whereas addition of HyEc inhibited this effect. CWF led to a significant increase of ASC migration (59·8%), compared with the control group (29·6%, P < 0·001). It was found that 1 mM of HyEc in addition to CWF significantly reduced migration rate to 46·4% (P = 0·019), whereas addition of 100 µm or 10 μM HyEc did not influence ASC migration significantly. HyEc alone in all concentrations significantly inhibited migration of ASC. Details are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Migration of adipose‐derived stem cells (ASC, transwell‐assay). Shown is the percentage of migrated (dark grey) and non‐migrated (light grey) ASC after 24 hours. Hydroxyectoine (HyEc) in concentrations of 10 μM, 100 μM and 1 mM, 2% chronic wound fluid (CWF) and 2% CWF plus HyEc in different concentrations were used as chemotactic stimuli. Culture media served as control (ctrl). Shown are the results of three independent experiments as mean ±SEM. Asterisks (*) indicate significance compared with control, plus signs (+) show significance compared with CWF (P < 0·05).

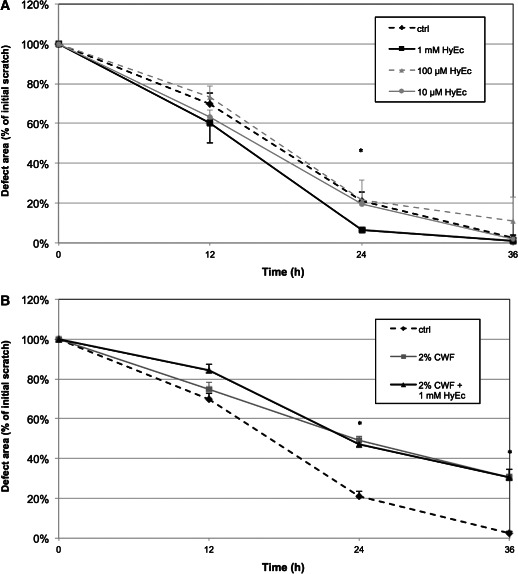

Migration of keratinocytes

HyEc alone had no significant effect on migration of keratinocytes in none of the tested concentrations. Only at 24 hours, a concentration of 1 mM led to a significant reduction of the cell‐free area compared with the control group (6·4% versus 21·3%, P < 0·001, Figure 4A); 1 mM of HyEc was used for further experiments together with CWF.

Figure 4.

Migration of keratinocytes (scratch‐assay). Diagrammed is the reduction of the initial defect area in the monolayer cell culture under the influence of (A) different concentrations of hydroxyectoine (HyEc): 1 mM (black line), 100 μM (dashed grey line), 10 μM (grey line) and (B) 2% chronic wound fluid (CWF, grey line) and 2% CWF plus 1 mM HyEc (black line). The dashed black line represents the control group (culture medium). Shown are the results of three independent experiments as mean + SEM. *P < 0·05.

Twelve hours after incubation, the cell‐free area of the control group was smallest (70%). Influenced by CWF the defect area was slightly enlarged (74·9%), indicating an impaired migration of keratinocytes; 1 mM of HyEc worsened this effect (84·4%). After 24 hours, the remaining cell‐free area decreased to 21·3% in the control group. CWF further inhibited migration, leading to a cell‐free area of 49·1% (P = 0·010). The CWF/HyEc group showed a cell‐free area of 47% (P = 0·022). While in vitro wound closure after 36 hours was nearly completed in the control group (2·5%), the cell‐free area was significantly larger with CWF (30·4%, P < 0·001), which was not influenced by HyEc (30·5%, P = 0·020). Results are demonstrated in Figure 4B.

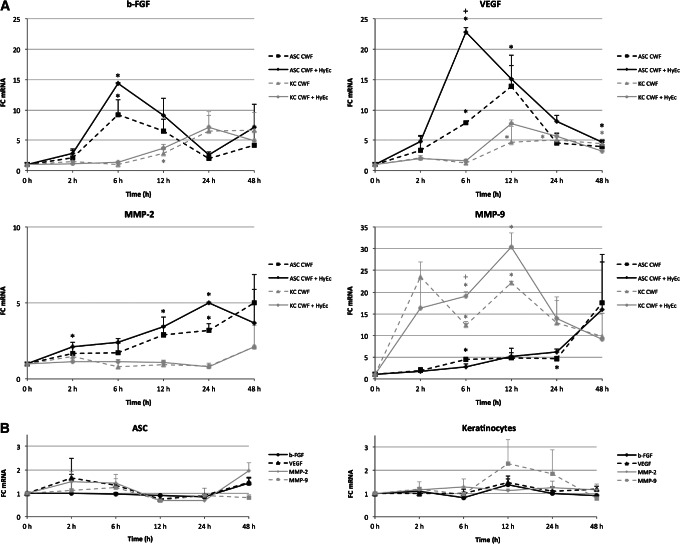

Gene expression patterns of ASC and keratinocytes

On the basis of the above mentioned results, for this experiment HyEc was used only in a concentration of 1 mM. CWF strongly induced expression of b‐FGF, VEGF and MMP‐9 after 6 hours and that of MMP‐2 after 24 hours in ASC. HyEc significantly enhanced this effect for VEGF (P < 0·05) and upregulation occurred earlier. Keratinocytes reacted similarly, but induction of gene expression was observed later and was less pronounced. Expression of b‐FGF, VEGF and MMP‐9 was significantly upregulated by CWF, whereas HyEc further enhanced gene expression only of MMP‐9 after 6 hours (P < 0·05). MMP‐2 expression was not affected in keratinocytes. Results are shown in Figure 5A. HyEc alone did not significantly affect gene expression patterns of ASC and keratinocytes at any time (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Gene expression changes of adipose‐derived stem cells (ASC) and keratinocytes. (A) Keratinocytes (KC, grey lines) and ASC (black lines) were treated with 2% chronic wound fluid (CWF, dashed lines) or 2% CWF plus 1 mM hydroxyectoine (HyEc, continuous lines) for 2, 6, 12, 24 and 48 hours or left untreated. (B) Influence over time of 1 mM HyEc on keratinocyte and ASC gene expression of basic fibroblast growth factor (b‐FGF, black lines), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF, dashed black lines), matrix metalloproteinases‐2 (MMP‐2, grey lines) and MMP‐9 (dashed grey lines). Fold‐changes (FC) of gene expression were analysed by quantitative real‐time polymerase chain reaction and plotted as mean + SEM. Asterisks indicate significant differences in gene expression compared with the control group and plus‐signs between CWF/HyEc group and CWF group with P < 0·05 (n = 3).

Discussion

Chronic wounds are characterised by a prolonged and complicated healing process. Resident and attracted cells are impaired by the local wound environment, representing the consequences of insufficient oxygen supply and accumulation of metabolites resulting from poor blood perfusion. We used a common method to transfer the microenvironment of chronic sacral decubitus into an in vitro wound model. The aim of this study was to examine the effect of HyEc on ASC and keratinocyte function in chronic wounds in vitro.

Migration of keratinocytes was significantly inhibited by CWF. These changes are based on a variety of influencing factors. The imbalance of regulatory growth factors, cytokines and degrading proteases and their inhibitors in CWF appears to be one of the main reasons for decelerated cell functions 9. Keratinocytes located at the wound margin are determined to proliferate and migrate along the wound bed for final wound closure. Fibronectin is one of the key extracellular matrix proteins in wound healing and important for adhesion and migration of keratinocytes 25. For reepithelialisation an efficient interaction between fibronectin and its receptor α5β1 is required. Although fibronectin mRNA is markedly increased in chronic wounds 26, cell migration is impaired. This is explained by an elevated protease activity in CWF leading to degradation of fibronectin 27, and a lack of the binding α5β1 receptor in keratinocyte cell membranes 28. Wound infection might play another important role in impaired wound healing. All chronic wounds are secondary colonised by bacteria from the surrounding skin or the local environment 29. Lipopolysaccharides (LPS) are found in the outer membrane of Gram‐negative bacteria and act as endotoxins. Loryman and Mansbridge showed that LPS decreased keratinocyte migration in vitro 30.

In contrast, migration of ASC was significantly stimulated by CWF compared with the control group. Chemokines like stromal cell‐derived factor‐1 (SDF‐1)/CXCL‐12 and their receptor CXCR‐4 are involved in stem cell migration to the site of injury 31. To our knowledge there is no evidence about the level of SDF‐1 or other important chemoattractants in CWF. However, proinflammatory chemokines such as TNF‐α and IL‐1 are elevated in CWF 32, and might also play a role in ASC recruitment by stimulating cell migration 33.

While proliferation of ASC was not affected by CWF, consistent with the literature, keratinocyte proliferation was markedly reduced in this study 34, 35. Cell proliferation is regulated by EGF and other mitogenic growth factors 36. As it has been shown, CWF has the ability to degrade EGF and other proteins 9, and this might partly explain impaired proliferation of keratinocytes. In contrast Seah et al. postulated that lack of mitogenic growth factors is not responsible for the inhibitory effect of CWF, as they have shown that CWF affects a Ras‐mediated signalling pathway leading to a reduction of cellular proliferation 37. While keratinocyte viability is not affected by LPS 30, toxins secreted by specific bacteria may have the ability to induce cell death. Chronic wounds are mostly contaminated by multiple bacteria, but Staphylococcus aureus is predominantly detected in isolates 38. It has been shown that S. aureus produce profound cytotoxicity in keratinocytes via secreted staphylococcal alpha‐toxin 39. Although in this study CWF samples were passed through a sterile filter and bacterial contamination of the cell cultures was prevented, previous contained toxins might have been jointly responsible for the reduction of proliferation capacity.

ROS are involved in different pathological disorders such as mutagenesis, cancer, atherosclerosis and chronic wounds. As low levels of ROS in acute wounds are necessary for physiological wound healing 40, there is evidence that high levels are associated with the development of chronic wounds 41, 42. The role of ROS in cell damage is frequently investigated in dermatology. It has been shown that high levels of ROS induce apoptosis and necrosis of keratinocytes via different mechanisms 43, 44, 45. We treated our cells with HyEc, a potent osmolyte that is able to reduce cellular stress and might also have antioxidative effects 22, 46. No significant changes in viability of ASC and cell function of keratinocytes were observed after treatment with HyEc in this study. Reduced cell function under the influence of CWF did not improve after addition of HyEc in none of the tested concentrations. In contrast, HyEc even inhibited cell migration of ASC in the transwell‐assay either with or without CWF. These results suggest that cellular damage or dysfunction through CWF might not primarily be caused by osmotic or other type of cellular stress. One disadvantage of our study was that neither osmotic pressure nor pH value nor the levels of ROS were measured for quantification of cellular stress.

As ASC are likely to influence wound healing mainly via paracrine mechanisms, and keratinocytes are the most important resident cells, we analysed their protein expression patterns under the influence of CWF. By performing qRT‐PCR we focused on chemokines that are essential in wound healing, such as the angiogenic factors b‐FGF and VEGF. CWF significantly induced VEGF and b‐FGF expression by ASC and keratinocytes, whereas the effect on ASC was earlier and stronger than on keratinocytes. Interestingly, HyEc enhanced the effect on VEGF significantly. As angiogenesis is a key component of the physiological repair process, diminished VEGF production and therefore angiogenesis are likely to contribute to impaired tissue regeneration 47, 48. In this study VEGF was strongly induced by CWF, which might be due to tissue hypoxia in chronic wounds, activating the HIF‐1α pathway and thereby inducing VEGF expression 12. So a lack of angiogenic factor expression by ASC and keratinocytes appears not to be responsible for insufficient angiogenesis in chronic wounds. It has been previously shown that addition of MMP‐2‐ and MMP‐9‐inhibitors to CWF resulted in angiogenic stimulation, concluding that excessive levels of MMP‐2 and MMP‐9 as found in CWF impair angiogenesis 49. We analysed MMP‐2 and MMP‐9 expression influenced by CWF and observed significant induction of MMP‐2 expression by ASC and MMP‐9 in keratinocytes, which supports these findings. An excessively increased MMP‐2 expression by ASC and MMP‐9 expression by keratinocytes in the chronic wound environment might cause continuous self‐digestion of extracellular matrix (ECM) and thereby impair wound healing. Furthermore, MMP‐9 leads to degradation of growth factors and their receptors 50, and is likely to have a negative impact on cell proliferation51. In our study, HyEc again led to a further increase of MMP‐9 expression by stimulated keratinocytes, which could be explained by stabilisation effects towards proteins and biological macromolecules, including RNA 52, 53. However, HyEc alone had no influence on ASC and keratinocyte gene expression, implying that HyEc may affect only stimulated cells.

Conclusions

CWF negatively influenced proliferation and migration of keratinocytes, which was not influenced by HyEc. ASC proliferation was not affected by CWF, but migration was increased. HyEc inhibited ASC migration. Gene expression of b‐FGF, VEGF, MMP‐2 and MMP‐9 by ASC and b‐FGF, VEGF and MMP‐9 by keratinocytes is strongly induced through CWF. While HyEc alone did not affect gene expression, CWF‐induced expression of VEGF in ASC and MMP‐9 in keratinocytes was further enhanced. These findings might be explained by the RNA stabilising properties of HyEc, but appear to act only in stimulated cells.

Supporting information

Table S1. Primer sequences used for quantitative real‐time polymerase chain reaction

Acknowledgements

We thank the University of Witten/Herdecke for a grant supporting the research position of the last author.

The authors state that there is no conflict of interest following the guidelines of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. The manuscript, including related data, figures and tables has not been previously published and is not under consideration elsewhere. The BITOP AG Witten financially supported the experiments. The company provided the substance ‘hydroxyectoine’.

References

- 1. Sen CK, Gordillo GM, Roy S, Kirsner R, Lambert L, Hunt TK, Gottrup F, Gurtner GC, Longaker MT. Human skin wounds: a major and snowballing threat to public health and the economy. Wound Repair Regen 2009;17:763–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gillitzer R, Goebeler M. Chemokines in cutaneous wound healing. J Leukoc Biol 2001;69:513–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Akino K, Mineda T, Akita S. Early cellular changes of human mesenchymal stem cells and their interaction with other cells. Wound Repair Regen 2005;13:434–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Baker EA, Leaper DJ. Proteinases, their inhibitors, and cytokine profiles in acute wound fluid. Wound Repair Regen 2000;8:392–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Trengove NJ, Stacey MC, MacAuley S, Bennett N, Gibson J, Burslem F, Murphy G, Schultz G. Analysis of the acute and chronic wound environments: the role of proteases and their inhibitors. Wound Repair Regen 1999;7:442–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wysocki AB, Staiano‐Coico L, Grinnell F. Wound fluid from chronic leg ulcers contains elevated levels of metalloproteinases MMP‐2 and MMP‐9. J Invest Dermatol 1993;101:64–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Parks WC. Matrix metalloproteinases in repair. Wound Repair Regen 1999;7:423–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yager DR, Zhang LY, Liang HX, Diegelmann RF, Cohen IK. Wound fluids from human pressure ulcers contain elevated matrix metalloproteinase levels and activity compared to surgical wound fluids. J Invest Dermatol 1996;107:743–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tarnuzzer RW, Schultz GS. Biochemical analysis of acute and chronic wound environments. Wound Repair Regen 1996;4:321–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ko J, Jun H, Chung H, Yoon C, Kim T, Kwon M, Lee S, Jung S, Kim M, Park JH. Comparison of EGF with VEGF non‐viral gene therapy for cutaneous wound healing of streptozotocin diabetic mice. Diabetes Metab J 2011;35:226–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ortega S, Ittmann M, Tsang SH, Ehrlich M, Basilico C. Neuronal defects and delayed wound healing in mice lacking fibroblast growth factor 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1998;95:5672–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Holzbach T, Neshkova I, Vlaskou D, Konerding MA, Gansbacher B, Biemer E, Giunta RE. Searching for the right timing of surgical delay: angiogenesis, vascular endothelial growth factor and perfusion changes in a skin‐flap model. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2009;62:1534–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ono I. Roles of cytokines in wound healing processes. Nihon Geka Gakkai Zasshi 1999;100:522–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kaikai S, Yuchen S, Lili J, Zhengtao W. Critical role of c‐Jun N‐terminal kinase in regulating bFGF‐induced angiogenesis in vitro. J Biochem 2011;150:189–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lee SH, Lee JH, Cho KH. Effects of human adipose‐derived stem cells on cutaneous wound healing in nude mice. Ann Dermatol 2011;23:150–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nambu M, Kishimoto S, Nakamura S, Mizuno H, Yanagibayashi S, Yamamoto N, Azuma R, Kiyosawa T, Ishihara M, Kanatani Y. Accelerated wound healing in healing‐impaired db/db mice by autologous adipose tissue‐derived stromal cells combined with atelocollagen matrix. Ann Plast Surg 2009;62:317–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ebrahimian TG, Pouzoulet F, Squiban C, Buard V, Andre M, Cousin B, Gourmelon P, Benderitter M, Casteilla L, Tamarat R. Cell therapy based on adipose tissue‐derived stromal cells promotes physiological and pathological wound healing. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2009;29:503–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tarnuzzer RW, Macauley SP, Farmerie WG, Caballero S, Ghassemifar MR, Anderson JT, Robinson CP, Grant MB, Humphreys‐Beher MG, Franzen L, Peck AB, Schultz GS. Competitive RNA templates for detection and quantitation of growth factors, cytokines, extracellular matrix components and matrix metalloproteinases by RT‐PCR. Biotechniques 1996;20:670–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yeoh‐Ellerton S, Stacey MC. Iron and 8‐isoprostane levels in acute and chronic wounds. J Invest Dermatol 2003;121:918–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Inbar L, Lapidot A. Metabolic regulation in Streptomyces parvulus during actinomycin D synthesis, studied with 13C‐ and 15 N‐labeled precursors by 13C and 15N nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy and by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. J Bacteriol 1988;170:4055–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lippert K, Galinski EA. Enzyme stabilization be ectoine‐type compatible solutes: protection against heating, freezing and drying. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 1992;37:61–5. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Harishchandra RK, Wulff S, Lentzen G, Neuhaus T, Galla HJ. The effect of compatible solute ectoines on the structural organization of lipid monolayer and bilayer membranes. Biophys Chem 2010;150(1–3):37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dominici M, Le Blanc K, Mueller I, Slaper‐Cortenbach I, Marini F, Krause D, Deans R, Keating A, Prockop D, Horwitz E. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy 2006;8:315–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Liu W, Saint DA. A new quantitative method of real time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction assay based on simulation of polymerase chain reaction kinetics. Anal Biochem 2002;302:52–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. O'Keefe EJ, Payne RE Jr, Russell N, Woodley DT. Spreading and enhanced motility of human keratinocytes on fibronectin. J Invest Dermatol 1985;85:125–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ongenae KC, Phillips TJ, Park HY. Level of fibronectin mRNA is markedly increased in human chronic wounds. Dermatol Surg 2000;26:447–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Grinnell F, Ho CH, Wysocki A. Degradation of fibronectin and vitronectin in chronic wound fluid: analysis by cell blotting, immunoblotting, and cell adhesion assays. J Invest Dermatol 1992;98:410–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Widgerow AD. Chronic wounds ‐ is cellular 'reception' at fault? Examining integrins and intracellular signalling. Int Wound J 2013;10:185–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Siddiqui AR, Bernstein JM. Chronic wound infection: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol 2010;28:519–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Loryman C, Mansbridge J. Inhibition of keratinocyte migration by lipopolysaccharide. Wound Repair Regen 2008;16:45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kroeze KL, Jurgens WJ, Doulabi BZ, van Milligen FJ, Scheper RJ, Gibbs S. Chemokine‐mediated migration of skin‐derived stem cells: predominant role for CCL5/RANTES. J Invest Dermatol 2009;129:1569–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wiegand C, Schonfelder U, Abel M, Ruth P, Kaatz M, Hipler UC. Protease and pro‐inflammatory cytokine concentrations are elevated in chronic compared to acute wounds and can be modulated by collagen type I in vitro. Arch Dermatol Res 2010;302:419–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bocker W, Docheva D, Prall WC, Egea V, Pappou E, Rossmann O, Popov C, Mutschler W, Ries C, Schieker M. IKK‐2 is required for TNF‐alpha‐induced invasion and proliferation of human mesenchymal stem cells. J Mol Med (Berl) 2008;86:1183–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bucalo B, Eaglstein WH, Falanga V. Inhibition of cell proliferation by chronic wound fluid. Wound Repair Regen 1993;1:181–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mendez MV, Raffetto JD, Phillips T, Menzoian JO, Park HY. The proliferative capacity of neonatal skin fibroblasts is reduced after exposure to venous ulcer wound fluid: a potential mechanism for senescence in venous ulcers. J Vasc Surg 1999;30:734–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pardee AB. G1 events and regulation of cell proliferation. Science 1989;246:603–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Seah CC, Phillips TJ, Howard CE, Panova IP, Hayes CM, Asandra AS, Park HY. Chronic wound fluid suppresses proliferation of dermal fibroblasts through a Ras‐mediated signaling pathway. J Invest Dermatol 2005;124:466–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bowler P. The anaerobic and aerobic microbiology of wounds: a review. Wounds 1998;10:170–8. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ezepchuk YV, Leung DY, Middleton MH, Bina P, Reiser R, Norris DA. Staphylococcal toxins and protein A differentially induce cytotoxicity and release of tumor necrosis factor‐alpha from human keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol 1996;107:603–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Schafer M, Werner S. Oxidative stress in normal and impaired wound repair. Pharmacol Res 2008;58:165–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. White MJ, Heckler FR. Oxygen free radicals and wound healing. Clin Plast Surg 1990;17:473–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Senel O, Cetinkale O, Ozbay G, Ahcioglu F, Bulan R. Oxygen free radicals impair wound healing in ischemic rat skin. Ann Plast Surg 1997;39:516–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Jin GH, Liu Y, Jin SZ, Liu XD, Liu SZ. UVB induced oxidative stress in human keratinocytes and protective effect of antioxidant agents. Radiat Environ Biophys 2007;46:61–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gronberg A, Zettergren L, Bergh K, Stahle M, Heilborn J, Angeby K, Small PL, Akuffo H, Britton S. Antioxidants protect keratinocytes against M. ulcerans mycolactone cytotoxicity. PLoS One 2010;5:e13839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pourzand C, Tyrrell RM. Apoptosis, the role of oxidative stress and the example of solar UV radiation. Photochem Photobiol 1999;70:380–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cornacchione S, Sadick NS, Neveu M, Talbourdet S, Lazou K, Viron C, Renimel I, de Q ueral D, Kurfurst R, Schnebert S, Heusele C, Andre P, Perrier E. In vivo skin antioxidant effect of a new combination based on a specific Vitis vinifera shoot extract and a biotechnological extract. J Drugs Dermatol 2007;6(6 Suppl):s8–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bao P, Kodra A, Tomic‐Canic M, Golinko MS, Ehrlich HP, Brem H. The role of vascular endothelial growth factor in wound healing. J Surg Res 2009;153:347–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Galiano RD, Tepper OM, Pelo CR, Bhatt KA, Callaghan M, Bastidas N, Bunting S, Steinmetz HG, Gurtner GC. Topical vascular endothelial growth factor accelerates diabetic wound healing through increased angiogenesis and by mobilizing and recruiting bone marrow‐derived cells. Am J Pathol 2004;164:1935–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ulrich D, Lichtenegger F, Unglaub F, Smeets R, Pallua N. Effect of chronic wound exudates and MMP‐2/‐9 inhibitor on angiogenesis in vitro. Plast Reconstr Surg 2005;116:539–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ladwig GP, Robson MC, Liu R, Kuhn MA, Muir DF, Schultz GS. Ratios of activated matrix metalloproteinase‐9 to tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase‐1 in wound fluids are inversely correlated with healing of pressure ulcers. Wound Repair Regen 2002;10:26–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Gill SE, Parks WC. Metalloproteinases and their inhibitors: regulators of wound healing. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2008;40(6–7):1334–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Knapp S, Ladenstein R, Galinski EA. Extrinsic protein stabilization by the naturally occurring osmolytes beta‐hydroxyectoine and betaine. Extremophiles 1999;3:191–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Mascellani N, Liu X, Rossi S, Marchesini J, Valentini D, Arcelli D, Taccioli C, Helmer C itterich M, Liu CG, Evangelisti R, Russo G, Santos JM, Croce CM, Volinia S. Compatible solutes from hyperthermophiles improve the quality of DNA microarrays. BMC Biotechnol 2007;7:82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Primer sequences used for quantitative real‐time polymerase chain reaction