Abstract

An increasing number of compression systems available for treatment of venous leg ulcers and limited evidence on the relative effectiveness of these systems are available. The purpose of this study was to conduct a randomised controlled trial to compare the effectiveness of a four‐layer compression bandage system and Class 3 compression hosiery on healing and quality of life (QL) in patients with venous leg ulcers. Data were collected from 103 participants on demographics, health, ulcer status, treatments, pain, depression and QL for 24 weeks. After 24 weeks, 86% of the four‐layer bandage group and 77% of the hosiery group were healed (P = 0·24). Median time to healing for the bandage group was 10 weeks, in comparison with 14 weeks for the hosiery group (P = 0·018). The Cox proportional hazards regression found participants in the four‐layer system were 2·1 times (95% CI 1·2–3·5) more likely to heal than those in hosiery, while longer ulcer duration, larger ulcer area and higher depression scores significantly delayed healing. No differences between groups were found in QL or pain measures. Findings indicate that these systems were equally effective in healing patients by 24 weeks; however, a four‐layer system may produce a more rapid response.

Keywords: Compression; Quality of life; Varicose ulcer; Wound healing

Introduction

Venous leg ulcers are often slow to heal and result in long‐term suffering and intensive use of health care resources 1, 2. In addition to direct costs to the health care system, chronic leg ulcers are associated with significant hidden burdens on the community. These include costs associated with lost productivity, the social support systems (both community and government funded) necessary for people who are unable to mobilise freely and high personal costs associated with home care of the ulcers (3). Patients report that leg ulcers are associated with prolonged periods of restricted mobility, decreased functional ability, pain, social isolation and decreased quality of life (QL) 4, 5, 6.

Around 70% of chronic leg ulcers are caused by venous disease and evidence shows that compression therapy is an effective treatment (7). However, the ever‐increasing variety of compression systems and limited evidence on comparative effectiveness can lead to uncertainty and inconsistency in treatment decisions. In addition, the wide variation between differing compression systems with regard to costs, requirement for expertise to apply, comfort and ease of application points to an urgent need for information on the relative effectiveness of these systems for both clinicians and consumers.

A systematic review in 2009 found that the use of multilayered high‐compression systems was more effective than use of single‐layered low‐compression systems, and multilayered systems including an elastic component were more effective than non‐elastic systems (7). A debate continues on the optimal type and level of multilayered compression systems, and a number of trials comparing short‐stretch and long‐stretch multilayered systems have been undertaken 8, 9, 10. However, there are a few comparisons of other types of systems and even fewer looking at compression hosiery, despite the frequent use of compression hosiery in clinical practice. A combined analysis of two studies comparing two‐layered compression hosiery and short‐stretch bandaging 11, 12 found that compression hosiery resulted in higher healing rates (7), while two other studies comparing compression hosiery with paste bandages found no significant differences in healing 13, 14.

The purpose of this study was to compare the effectiveness of a four‐layer compression bandage system and a Class 3 (30–35 mmHg) compression hosiery system on healing and QL outcomes.

Hypothesis

There will be no difference in healing or QL outcomes at 24 weeks between patients receiving a four‐layer bandage compression system and those receiving a Class 3 compression hosiery system.

Methods

A randomised controlled trial was undertaken to determine the effectiveness of a four‐layer compression bandage system in comparison with a Class 3 compression hosiery system on healing and QL at 24 weeks in patients with venous leg ulcers. Recruitment and data collection occurred from September 2006 to August 2009.

Sample

All patients fulfilling the inclusion and exclusion criteria and admitted to outpatient leg ulcer clinics run by metropolitan hospitals or two community nursing services were invited to participate in this study.

Inclusion criteria

Patients with leg ulcers of venous aetiology.

Ankle Brachial Pressure Index ≥0·8 and <1·3.

Ulcer size of ≥1 cm2.

When more than one ulcer was present, the largest ulcer was identified as a target ulcer for the purpose of this study.

Exclusion criteria

Patients unable to mobilise, that is completely bound to bed or wheelchair bound.

Ankle Brachial Pressure Index <0·8 or ≥1·3.

Patients with cognitive impairment.

Presence of clinical signs of infection on admission.

Sample size calculations found that a sample of 154 participants would be required to detect a 20% difference in proportions of participants healed, as determined by power analysis with a type I error of 5% and 90% power, and allowing for 20% attrition (64 completing participants/group). Power analysis for the secondary outcomes (pain, depression, QL), based on identifying a significant clinical difference of 20/100 between mean group scores, with a type I error of 5% and 90% power and allowing for 20% attrition, found required sample sizes ranging from 52 (26/group for QL) to 80 (40/group for pain scale) participants required.

Data collection and measures

Data on demographics, health, medical history and ulcer characteristics were collected from medical records and patient questionnaires at baseline. Information on variables known to influence ulcer healing, that is ulcer size, duration and age 15, 16, were collected to include in the final analysis. Data on progress in healing and treatments were collected every second week for 24 weeks from baseline. A ‘healed’ leg ulcer was defined as full epithelialisation of the wound, which was maintained for 2 weeks. Data on QL measures were collected via a patient questionnaire at baseline, 12 weeks and 24 weeks from recruitment.

Instruments and measures

Progress in wound healing was measured with the following methods:

ulcer area was calculated from acetate wound tracings and use of a portable digital planimetry device to determine ulcer areas and percentage area reduction;

the Pressure Ulcer Scale for Healing (PUSH) tool for ulcer healing (17) was used to provide a broader measure of healing than examining area alone, covering area, exudate and the type of wound bed tissue (i.e. epithelial, granulating, slough or necrotic);

clinical data related to healing progress such as presence of oedema, eczema, inflammation and signs of infection were also collected. Ankle and calf circumference measurements were taken to check for changes in oedema every 2 weeks at two points: 2 cm above the medial malleolus and 5 cm below the tibial tuberosity.

QL measures included:

QL Index (18): The QL Index was developed for chronically ill patients and consists of five items measuring the domains of activity, daily living, health support and psychological outlook. Evidence of good validity and reliability has been reported in studies from Australia, Canada and the USA (19). Spitzer et al. (18) reported coefficient α = 0·77 for internal consistency and correlations from 0·74–0·84 for inter‐rater reliability (18).

Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) Pain Measures (20): This seven‐item questionnaire measures the intensity, frequency and duration of pain and records the impact of pain on daily living. The self‐report items cover two factors, severity and pain effects. Good internal consistency has been reported (21).

Geriatric Depression Scale (22): This screening scale was designed to be easily completed by older adults in an outpatient setting. The abbreviated 15‐item scale avoids problems of fatigue. Studies in varying settings have shown good reliability and high sensitivity (84%) and specificity (95%) among cognitively intact elderly people (21).

Procedure and protocol

On admission to the outpatient leg ulcer clinics, patients were assessed and those who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria, were invited to participate in the trial. An information package on this study was provided by a Research Assistant and explained to potential participants and signed consent obtained. Baseline data were collected prior to randomisation and thus blinded.

Following collection of baseline data, the Research Assistant at the clinical site opened a sequentially numbered envelope containing the names of randomised group participants. Randomisation was centrally generated via a computerised randomisation programme for the total expected sample size. An independent administration assistant assembled sealed sequentially numbered envelopes containing the randomised group allocation. These envelopes were divided into four sets (one for each recruitment site). Participants were randomised to either a four‐layer compression bandage system or a Class 3 (30–35 mmHg) compression hosiery system. A core team of wound care nurses at the clinics was trained in the protocol assessment, wound care and compression techniques for consistency. New staff members were also trained in study protocols throughout the study data collection phase.

The ulcers were cleansed with warm tap water and dressed with a non‐adherent, non‐medicated dressing. Patients with clinical signs of infection on admission were excluded from this study; however, if signs of infection developed during the course of this study, the clinician treated the infection appropriately and the patient continued in this study. All such events were documented to enable checks for confounders in analysis of data. Although the nurses assessing the ulcers and providing care were unable to be blinded from the type of compression being applied, the acetate ulcer tracings and wound photographs were assessed and area was calculated by an independent research assistant, who was blinded to group allocation.

Participants randomised to the bandage group had a four‐layer compression bandage system applied, while participants randomised to the Class 3 compression hosiery group were fitted for the correct hosiery size and shown how to apply and remove the hosiery with appropriate applicators if needed. Participants who were unable to manage their hosiery alone were referred to community nursing services or their General Practitioner Practice Nurse for assistance (n = 2, 4%). Compression hosiery could be removed at night, as long as it was replaced first thing in the morning.

Participants with very oedematous legs who were randomised to the compression hosiery group were placed in short‐stretch bandaging for 1–4 weeks until the oedema subsided prior to commencement of Class 3 compression hosiery (n = 9, 18%). A record was kept each week on how many days/week the compression systems were worn.

Analysis

Data were analysed with SPSSv15 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). Analysis was conducted following intention to treat according to the guidelines. Data were double entered and inconsistencies were checked and corrected according to the original records. Analysis was undertaken by an investigator not involved in data collection at the clinical sites using a group‐coded database. Baseline demographic, health, psychosocial, treatments and ulcer characteristics were analysed to check for comparability of the two compression groups. Descriptive analyses were undertaken for all variables. Median times to healing were calculated and compared using the Kaplan–Meier method and log‐rank test. A Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to adjust for potential confounders and analyse the effect of the two types of compression on healing. Plots of the survival curves for each variable were checked to test for proportionality of hazards. Multicollinearity checks were undertaken using a correlation matrix and examining Pearson or Spearman coefficients, and checking squared multiple correlations among covariates. A general linear model with repeated measures analysis was undertaken to investigate the differences in pain and QL measures over data collection points and between groups.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee at each of the organisations involved and complied with the Helsinki Declaration ethical rules for human experimentation. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Results

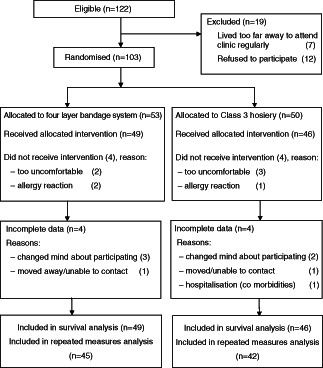

A sample of 103 patients was recruited to participate in this study. The flow of participants through this study and reasons for loss to follow‐up are shown in Figure 1. There was an overall attrition rate of 9·7% (n = 10) of participants over the 24 weeks. Participants who withdrew or were lost to follow‐up did not differ significantly from those who completed this study on baseline demographics, comorbidities or ulcer characteristics; however, they reported significantly lower QL scale scores (P = 0·01) and higher average pain scores (P = 0·005) on admission to this study in comparison with those who completed this study. There were no missing data in the demographic, health or ulcer variables; however, missing data were identified in the Geriatric Depression Scale items. The pattern of missing data was checked by testing differences between cases with missing data and cases with no missing data and no significant differences were found. Cases with more than five of the scale items missing were excluded from the analysis (n = 4), while cases with four or less scale items missing had their total score calculated according to the scale authors' algorithm (22). There were two adverse effects in the compression hosiery group (local sensitivity reactions) and three adverse effects in the four‐layer bandage group (two local sensitivity reactions and one bandage trauma).

Figure 1.

Flow of participants through study.

Baseline demographic characteristics, comorbidities and ulcer characteristics are shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences between groups for age, gender, living arrangements, health variables or ulcer characteristics. Looking at adherence to the compression protocols, 85% (n = 39) of those randomised to Class 3 hosiery reported that they were adherent (i.e. remained in compression six or more days/week) for at least three quarters of their time in this study and 15% (n = 7) for less than 75% of the study period. Of the participants randomised to the four‐layer bandage system, 88% (n = 43) reported that they were adherent for at least three quarters of their time in this study and 12% (n = 6) for less than 75% of the study period.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic, health and ulcer characteristics

| Characteristics | Four‐layer bandage group (n = 53) | Class 3 hosiery group (n = 50) | Total (n = 103) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | |||

| Age, mean ± SD | 67 ± 15·7 | 68 ± 14·1 | 68 ± 14·8 |

| Female (n, %) | 29, 55% | 22, 44% | 51, 50% |

| Lived alone (n, %) | 18, 34% | 13, 26% | 31, 30% |

| Comorbidities/health | |||

| Cardiac disease (n, %) | 16, 30% | 9, 18% | 25, 24% |

| Osteoarthritis (n, %) | 23, 43% | 16, 32% | 39, 38% |

| Rheumatoid disease (n, %) | 7, 13% | 4, 8% | 11, 11% |

| Diabetes (n, %) | 8, 15% | 7, 14% | 15, 15% |

| Previous DVT (n, %) | 10, 19% | 12, 24% | 22, 21% |

| Previous leg ulcers (n, %) | 38, 72% | 33, 69% | 71, 70% |

| Required aid to mobilise (n, %) | 16, 30% | 10, 20% | 26, 25% |

| Body mass index (mean ± SD) | 34 ± 11·5 | 33 ± 9·7 | 33 ± 10·7 |

| Ulcer characteristics | |||

| Ulcer area (median, range) | 4·6 cm2 (1–170) | 4·0 cm2 (1–114) | 4·1 cm2 (1–170) |

| Ulcer duration (median, range) | 19 weeks (1–312) | 25 weeks (1–364) | 23 weeks (1–364) |

| PUSH score (mean ± SD) | 10·7 ± 2·89 | 10·0 ± 2·56 | 10·4 ± 2·75 |

SD, standard deviation; DVT, deep vein thrombosis.

Ulcer healing outcomes

After 24 weeks of treatment, 84% of participants in the four‐layer system and 72% of those in Class 3 hosiery were healed (χ 2 = 2·16, P = 0·14). Mean percentage reduction in ulcer area was 96% (SD 15·6) for those in the four‐layer bandage group, and 93% (SD 14·9) for those in the Class 3 hosiery group (P = 0·27).

A survival analysis approach was taken to determine multivariable relationships between the compression groups, potential confounders and differences in proportions of ulcers healed, as recommended by Cullum et al. (23) and more recently O'Meara et al. (7), who noted that survival analysis provides a more meaningful estimate of treatment effect and that all trials assessing ulcer healing should adopt this analysis. At the bivariate level, Kaplan–Meier survival curve analysis found that median time to healing for the four‐layer group was 10 weeks, in comparison with 15 weeks for those in Class 3 hosiery (P = 0·003). Time to healing was also found to be significantly delayed for participants with an ulcer duration over 24 weeks on admission (P < 0·001), baseline ulcer area over 10 cm2 (P = 0·03), a PUSH score higher than 10 (P = 0·005), and scores >4 on the Geriatric Depression Scale (P = 0·012). Time to healing was significantly shorter for those taking diuretic medications (P = 0·002) at the bivariate level. No significant relationships were found between healing and age, gender, cormorbidities (diabetes, osteoarthritis, rheumatic disease, cardiovascular disease and autoimmune disease, past deep vein thrombosis), types of medications, restricted mobility (requiring a walking aid) and dressing type.

Cox proportional hazards regression model

All variables associated with healing at the bivariate level (P < 0·05) or identified in the literature as impacting on healing were entered simultaneously in the regression model. After mutual adjustment for all variables, analysis showed that the type of compression, ulcer duration and Geriatric Depression Scale scores remained significantly associated with healing. Participants in the four‐layer system were 2·4 times more likely to heal (95% CI 1·4–4·3) than those in Class 3 compression hosiery. In addition, patients with an ulcer duration >24 weeks were 2·3 times less likely to heal (95% CI 1·4–4·0) and those scoring at risk of depression were 2·1 times less likely to heal (95% CI 1·1–4·3). The proportional hazards regression model is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Hazard ratios for healing – Cox proportional hazards regression model

| β | Hazard ratio | 95% CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.015 | 1.02 | 0·99–1·03 | 0.101 |

| Taking diuretic medications | 0.311 | 1.37 | 0·76–2·43 | 0.291 |

| Ulcer area >10 cm2 | −0.677 | 0.51 | 0·22–1·00 | 0.051 |

| Ulcer duration >24 weeks | −0.950 | 0.39 | 0·22–0·67 | 0.001 |

| Compression type | Referent group | |||

| Class 3 compression hosiery | ||||

| Four‐layer bandage system | 0.91 | 2.49 | 1·44–4·29 | 0.001 |

| Depression (score >4 * ) | −0.762 | 0.47 | 0·23–0·96 | 0.037 |

*Geriatric Depression Scale Short Form – scale from 0 to 15, where scores of 5 or higher suggest depression.

QL outcomes

The two compression groups' mean scores and standard deviations for the QL Index, MOS Pain Measures Pain Severity Scale and Geriatric Depression Scale at baseline and at 24 weeks from baseline are shown in Table 3. General linear model repeated measures analysis showed no significant interaction effect or main effect for the QL Index scores. There were no significant interaction effects for the Geriatric Depression Scale scores or the MOS Pain scores; however, there were significant main effects for the Geriatric Depression Scale scores, with a small improvement over time from a mean score of 3·94 (SD 3·94) at baseline down to 3·88 (3·65), F = 4·72, P = 0·035, and for the MOS Pain Severity scores, which improved from an overall mean score of 50·8 (SD 27·1) at baseline (on a scale of 0–100, where 0 = no pain and 100 = worst pain possible) to a mean score of 28·9 (SD 23·1) at 24 weeks from baseline (F = 35·2, P < 0·001).

Table 3.

QL measures at baseline and at 24 weeks from baseline

| Mean (SD) at baseline | Mean (SD) at 24 weeks | Interaction effect | Main effect | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class 3 hosiery | Four‐layer bandages | Class 3 hosiery | Four‐layer bandages | F | P | F | P | |

| QL * | 8·33 (1·72) | 7·56 (2·20) | 8·36 (2·43) | 8·00 (2·36) | 1·19 | 0·278 | 1·51 | 0·223 |

| Depression † | 3·87 (3·84) | 4·04 (2·75) | 3·71 (3·76) | 4·13 (3·58) | 0·02 | 0·892 | 4·72 | 0·035 |

| Pain severity ‡ | 50·0 (26·4) | 51·8 (28·3) | 34·0 (23·3) | 23·0 (22·1) | 2·42 | 0·124 | 35·2 | <0·001 |

QL, quality of life.

*Range 0–10, where 0 = poor QL and 10 = excellent QL.

†Geriatric Depression Scale: range 0–15, where 0 = no depression and 15 = high risk of depression.

‡MOS pain measures: range 0–100, where higher scores indicate higher levels of pain.

Discussion

This study aimed to compare the effectiveness of a four‐layer compression bandage system and a Class 3 (30–35 mmHg) compression hosiery system on healing and QL outcomes. Results found that the four‐layer compression bandage system achieved significantly faster healing times, although there were no significant differences between the two groups in the proportions of healed patients after 24 weeks of treatment. QL and pain outcomes were similar for both compression groups.

These findings provide important evidence on the comparative effectiveness of these two compression systems for patients, their carers and health professionals. Previously reported evaluations of compression hosiery have had varying results, including favourable comparisons with short‐stretch compression bandages 11, 12, and no differences in healing were found in comparison with paste bandages 13, 14. As both multilayered bandage system and compression hosiery are widely used, further studies are important to build a strong body of evidence in this area and enable patients and health professionals to make informed choices.

Ulcer duration remained significantly associated with healing in this sample, as is frequently reported in the literature 16, 24, 25, 26. For example, Meaume et al. (25) specified an ulcer duration over 3 months as associated with prolonged healing, and Margolis et al. (16) reported that ulcers over 10 cm2 in size and lasting over 12 months had a 78% chance of not healing after 24 weeks of treatment. This consistent risk factor shows the urgent need for early identification of ulcers at high risk of poor healing outcomes in order to implement early interventions and break the long duration – hard to heal cycle that develops.

Ulcer size has also been previously identified as a risk factor. In general, the larger the ulcer, the more delayed the healing process 16, 25, 27, 28. This trend was showed in this sample, although ulcer area did not quite reach statistical significance in the multivariable model.

Importantly, depression was found to be significantly independently associated with healing in this study. Although depression and anxiety have been shown to delay acute wound healing 29, 30, there is an absence of research on the relationship between poor mental health and healing in chronic leg ulcers. It is known that a significant number of patients with leg ulcers have problems with depression and anxiety and significant correlations have been found between patients' psychological and spiritual well being and the number of venous ulcers experienced 6, 31, 32. Moffatt et al. (33) found that patients with leg ulcers were more likely to be depressed than matched controls without leg ulcers, and Wong and Lee (34) found that there was a significant correlation between patients with better emotional status and a higher likelihood of healing. These findings suggest that all patients with leg ulcers may benefit from screening and appropriate interventions for depression and further research is indicated in this area.

Limitations

Although only a small number of participants were lost to follow‐up (10%), participants who withdrew or were lost to follow‐up reported significantly lower QL and higher levels of pain on admission to this study in comparison with those who completed this study, suggesting that a small subgroup of patients may not be suitable for these treatments. Measures of health‐related QL and pain were obtained from self‐report questionnaires, with the possibility of response bias.

Conclusions

From a clinical care perspective, findings indicate that these two compression systems are equally effective in healing patients after 24 weeks, although a four‐layer system may produce a more rapid response. This study provides an improved understanding of wound healing in venous leg ulcers to facilitate development of improved treatment regimes and inform the practice of health care professionals caring for patients with venous leg ulcers. This new information has the potential to improve ulcer healing rates and QL and reduce health care costs.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Robin Armstrong, Megan Pratt, Patricia Shuter, Sisi Mahlangu, and the nursing and medical staff at the participating hospitals and community nursing services for their contribution. This study was funded by an Australian National Health and Research Medical Council Project Grant ID 390102. Trial Registration No. ACTRN12611000224921 (Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry).

References

- 1. Anand S, Dean C, Nettleton R, Praburaj D. Health‐related quality of life tools for venous‐ulcerated patients. Br J Nurs 2003;12:48–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Abbade LPF, Lastoria S. Venous ulcer: epidemiology, physiopathology, diagnosis and treatment. Int J Dermatol 2005;44:449–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gordon LG, Edwards H, Courtney M, Finlayson K, Shuter P, Lindsay E. A cost‐effectiveness analysis of two community models of nursing care for managing chronic venous leg ulcers. J Wound Care 2006;15:348–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brem H, Kirsner RS, Falanga V. Protocol for the successful treatment of venous ulcers. Am J Surg 2004;188:1S–8S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Franks PJ, McCullagh L, Moffat C. Assessing quality of life in patients with chronic leg ulceration using the Medical Outcomes Short Form‐36 questionnaire. Ostomy Wound Manage 2003;49: 26–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Persoon A, Heinen MM, van der Vleuten CJM, de Rooij MJ, van de Kerkhof PCM, van Achterberg T. Leg ulcers: a review of their impact on daily life. J Clin Nurs 2004;13:341–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. O'Meara S, Cullum N, Nelson E. Compression for venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;2:CD000265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Franks PJ, Moody M, Moffatt CJ, Martin R, Blewett R, Seymour E, Hledreth A, Hourican C, Collins J, Heron A. Randomized trial of cohesive short‐stretch versus four‐layer bandaging in the management of venous ulceration. Wound Repair Regen 2004;12:157–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Partsch H, Damstra RJ, Tazelaar DJ, Schuller‐Petrovic S, Velders AJ, de Rooij MJ, Sang RR, Quinlan D. Multicentre, randomised controlled trial of four‐layer bandaging versus short‐stretch bandaging in the treatment of venous leg ulcers. VASA 2001;30:108–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nelson EA, Iglesias CP, Cullum N, Torgerson DJ. Randomized clinical trial of four‐layer and short‐stretch compression bandages for venous leg ulcers (VenUS I). Br J Surg 2004;91:1292–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Junger M, Wollina U, Kohnen R, Rabe E. Efficacy and tolerability of an ulcer compression stocking for therapy of chronic venous ulcer compared with a below‐knee compression bandage: results from a prospective, randomized, multicentre trial. Curr Med Res Opin 2004;20:1613–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Polignano R, Guarnera G, Bonadeo P. Evaluation of SurePress comfort: a new compression system for the management of venous leg ulcers. J Wound Care 2004;13:387–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hendricks WM, Swallow RT. Management of statis leg ulcers with Unna's boots versus elastic support stockings. J Am Acad Dermatol 1985;12:90–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Koksal C, Bozkurt AK. Combination of hydrocolloid dressing and medical compression stocking versus Unna's boot for the treatment of venous leg ulcers. Swiss Med Wkly 2003;133:364–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Barwell JR, Ghauri ASK, Taylor M, Deacon J, Wakely C, Poskitt KR, Whyman MR. Risk factors for healing and recurrence of chronic venous leg ulcers. Phlebology 2000;15:49–52. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Margolis DJ, Allen‐Taylor L, Hoffstad O, Berlin JA. The accuracy of venous leg ulcer prognostic models in a wound care system. Wound Repair Regen 2004;12:163–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel. Pressure Ulcer Scale for Healing (Version 3.0) 1998. URL http://www.npuap.org/push3‐0.htm [accessed on 21 September 2011]

- 18. Spitzer WO, Dobson AJ, Hall J, Chesterman E, Levi J, Shepherd R, Battista RN, Catchlove BR. Measuring the quality of life of cancer patients: a concise QL‐index for use by physicians. J Chronic Dis 1981;34:585–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bowling A. Measuring health: a review of the quality of life measurement scales, 2nd edn. Buckingham: Open University Press, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sherbourne C. Pain measures. In: Stewart A, Ware J, editors. Measuring functioning and well‐being: the medical outcomes study approach. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1992:220–34. [Google Scholar]

- 21. McDowell I, Newell C. Measuring health: a guide to rating scales and questionnaires, 2nd edn. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Brink T, Yesavage J, Lum O, Heersema P, Adey M, Rose T. Screening tests for geriatric depression: Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS). Clin Gerontol 1982;1:37–44. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cullum N, Nelson EA, Fletcher AW, Sheldon TA. Compression for venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2001;2:CD000265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gohel MS, Taylor M, Earnshaw JJ, Heather BP, Poskitt KR, Whyman MR. Risk factors for delayed healing and recurrence of chronic venous leg ulcers ‐ an analysis of 1324 legs. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2005;29:74–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Meaume S, Couilliet D, Vin F. Prognostic factors for venous ulcer healing in a non‐selected population of ambulatory patients. J Wound Care 2005;14:31–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Moffatt CJ, Doherty DC, Smithdale R, Franks PJ. Clinical predictors of leg ulcer healing. Br J Dermatol 2010;162:51–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Iglesias C, Nelson EA, Cullum NA, Torgerson DJ. VenUS I: a randomised controlled trial of two types of bandage for treating venous leg ulcers. Health Technol Assess 2004;8:1–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Stacey MC, Jopp‐Mckay AG, Rashid P, Hoskin SE, Thompson PJ. The influence of dressings on venous ulcer healing ‐ a randomised trial. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 1997;13:174–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cole‐King A, Harding KG. Psychological factors and delayed healing in chronic wounds. Psychosom Med 2001;63:216–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Doering L, Moser D, Lemankiewicz W, Luper C, Khan S. Depression, healing, and recovery from coronary artery bypass surgery. Am J Crit Care 2005;14:316–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hareendran A, Bradbury A, Budd J, Geroulakos G, Hobbs R, Kenkre J, Symonds T. Measuring the impact of venous leg ulcers on quality of life. J Wound Care 2005;14:53–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jones J, Barr W, Robinson J, Carlisle C. Depression in patients with chronic venous ulceration. Br J Nurs 2006;15:S17–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Moffatt CJ, Franks PJ, Doherty D, Smithdale R, Steptoe A. Psychological factors in leg ulceration: a case‐control study. Br J Dermatol 2009;161:750–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wong IKY, Lee DTF. Chronic wounds: why some heal and others don't? Psychosocial determinants of wound healing in older people. HK J Dermatol & Venereol 2008;16:71–6. [Google Scholar]