Abstract

The foundation of health care management of patients with non‐healing, chronic wounds needs accurate evaluation followed by the selection of an appropriate therapeutic strategy. Assessment of non‐healing, chronic wounds in clinical practice in the Czech Republic is not standardised. The aim of this study was to analyse the methods being used to assess non‐healing, chronic wounds in inpatient facilities in the Czech Republic. The research was carried out at 77 inpatient medical facilities (8 university/faculty hospitals, 63 hospitals and 6 long‐ term hospitals) across all regions of the Czech Republic. A mixed model was used for the research (participatory observation including creation of field notes and content analysis of documents for documentation and analysis of qualitative and quantitative data). The results of this research have corroborated the suspicion of inconsistencies in procedures used by general nurses for assessment of non‐healing, chronic wounds. However, the situation was found to be more positive with regard to evaluation of basic/fundamental parameters of a wound (e.g. size, depth and location of a wound) compared with the evaluation of more specific parameters (e.g. exudate or signs of infection). This included not only the number of observed variables, but also the action taken. Both were significantly improved when a consultant for wound healing was present (P = 0·047). The same applied to facilities possessing a certificate of quality issued by the Czech Wound Management Association (P = 0·010). In conclusion, an effective strategy for wound management depends on the method and scope of the assessment of non‐healing, chronic wounds in place in clinical practice in observed facilities; improvement may be expected following the general introduction of a ‘non‐healing, chronic wound assessment’ algorithm.

Keywords: Chronic wounds, Clinical guidelines, Nursing practice, Wound assessment, Wound management

Introduction

Non‐healing, chronic wounds are a major socio‐economic problem whose solution requires a multidisciplinary approach. In the Czech Republic, nurses are the patients' carers who are mostly responsible for wound assessment in the inpatient facilities. They are also a source of information for doctors in making decisions about appropriate therapeutic procedures. This holistic and systematic approach to wound care also involves initial and ongoing wound assessment 1, 2, 3. An accurate assessment should help nurses to monitor the progress of a wound, and enable them to plan appropriate interventions and selection of dressings 4, 5 according to their competencies. In the Czech Republic, nurses are not allowed to select dressings for their patients, even if they have acquired additional education and certification. They are all obliged to inform a doctor about the condition of patients' wounds, whether there is improvement or deterioration, and collaborate with the doctor in planning the best treatment strategy. According to Czech law, nurses should contribute to the process of treatment, particularly as a source of information, and act as observers in the holistic and longer term care of the patients. It is understood that the role of nurses in wound management is as important as in other countries, but there is still no official recognition for tissue viability or wound specialist nurses, as there is in the UK or USA. However, doctors and nurses in the Czech Republic do understand the need for cooperation and mutual transfer of information. The number of nurses who are competent in accurate wound assessment will have to increase to keep pace with the rising number of patients presenting with non‐healing, chronic wounds, which has significant financial implications.

The increasing number of patients presenting with non‐healing, chronic wounds presents a challenge for health care systems worldwide. In the industrialised world, 1–1·5% of the general population has a chronic wound at any given time. In addition, chronic wound management is expensive; in Europe, the average cost per episode is €6650 for leg ulcers and €10 000 for diabetic foot ulcers and, overall, wound management accounts for 2–4% of health care budgets 6, 7, 8. In the Czech Republic, there is a legislative restriction on nurses' choice of dressing. Thus, the role of nursing is undervalued and underutilised and is not being given sufficient attention by doctors. This may be one of the reasons why nurses do not always consider the rating of wound assessment as important in their health care role and do not implement it in their care plans. This needs to change, and it could be addressed by better education. In the Czech Republic, there are a few courses that focus on undergraduate medical education in wound healing and that are optional subjects for bachelor's or master's degrees. Nurses are able to undertake postgraduate education only through certified courses, rather than through higher degrees, and even though they acquire special knowledge and skills, the latter are not always accepted by doctors 9, 10. These disparities with respect to education in wound care have been observed by other international scientific groups 11, 12, 13, 14. In the Czech Republic, there are no nurse specialists, such as tissue viability nurses, but some nurses who are more experienced, and have attended certified courses, could work as wound nurse consultants 9. They also have untapped experience, knowledge and skills in dealing with different types of wounds. In contrast, most general nurses do not have this level of expertise and need the support of these potential nurse consultants for education and for keeping themselves up to date with advances in wound care 15 and changing terminology 16. In addition, nurses currently use only the practices prevalent in their local clinical areas of practice (surgical, medical, dermatology) or in the hospital or community environment in which they work 10, 13. Improvement in nursing education, through better theoretical knowledge and experience of responsibility, should lead to an improved quality of evaluation of chronic wounds and better care, particularly the ability for early recognition of delayed healing and its causes. There is also the need for recognition of nurses' extended role in chronic wound management in multidisciplinary teams, together with a national standard for the care of patients with non‐healing wounds, in the Czech Republic.

Purpose of the study

The purpose of this study was to ascertain whether assessment and evaluation of chronic wounds varies among hospitals in the Czech Republic, and to identify problematic areas and recognise which of them might affect wound assessment and outcomes and could be improved. The chronic wound characteristics considered were based on published recommendations 17, 18, 19. The principles of the TIME model 20, 21, which offers a comprehensive approach to wound monitoring in addition to the risk factors that can help identify patients with non‐healing chronic wounds, were used for the study – Tissue (non‐viable or deficient), Infection or Inflammation, Moisture (balance or imbalance) and Edge of wound (non‐advancing or undermined). Another original mnemonic was also used: MEASURE – Measure (length, width, depth and area), Exudate (quantity and quality), Appearance (wound bed), Suffering (pain), Undermining, Re‐evaluate (wound treatment effectiveness) and Edge (condition of edge and surrounding skin) 21. These tools were chosen because they offer an understanding of why wounds do not heal, based on the underlying aetiologies, and why appropriate treatments are effective 20, 22. Other observed clinical parameters and information considered to be important for comprehensive assessment were added whenever nurses reported them in the patient's notes.

Methodological design and statistical analysis

The aim of the study was to ascertain, map and analyse methods of evaluation, with documentation, of non‐healing wounds, used in clinical practice in inpatient facilities in the Czech Republic. The objectives were to determine which parameters of non‐healing chronic wounds were the most reviewed/assessed/reported:

Are objective scales used for the evaluation of non‐healing chronic wounds, and if so, which scales are used?

How does the process of evaluation of wound variables differ in various facilities/hospitals, and how does it relate to the following determinants:

type of accreditation (proactive strategy to maintain the quality)

type of workplace (surgical, internal)

the presence of a consultant for wound healing

assigned/awarded certification of Czech Wound Management Association (CWMA)

the use of objective scales for assessment of patients

a declared interest in further information about the evaluation of non‐healing chronic wounds

the kind of strategy to be adopted to implement the recommended procedure for objective evaluation of non‐healing wounds in clinical practice

Wound parameters were divided into basic and specific groups. The ten basic (fundamental) wound parameters were the following: wound aetiology, wound duration, size, depth, localisation, edge and state of surrounding skin, wound bed, and local and systemic therapy. Nurses were graded according to their reporting; when they recorded this information they were given 1 point. They could obtain 2 points for recording each parameter using an objective scale (not including aetiology, time of wound presence and local or systemic therapy). Scales were created for the number of reported basic variables from 0 to 10, and for objective recording from 0 to 16 points. Specific monitored wound parameters included signs of inflammation/infection, exudate, odour, level of contamination or colonisation (determined by swab culture, for example), comorbidities and pain. The scale for the number of specific parameters ranged from 0 to 6 points, and that for objective recording ranged from 0 to 9 points (inflammation, exudate and pain were the specific variables easily recognised in the range). The health care facilities where nurses reported a greater number of signs and symptoms and used more objective methods (scales, ranges) were considered better than others because they met the optimal criteria for wound assessment.

A mixed research design with quantitative and qualitative elements at multiple levels (multilevel approach) was used with intentionally induced assigned selection. The basic premise was that the use of the qualitative and quantitative approaches in combination allows a better understanding of the research challenge 23, 24. Scientific observation is characterised by a precisely defined objective and is carried out by establishing a process whereby all data are systematically recorded 25. All 187 hospitals operating in the Czech Republic were addressed according to the information from National Directory of Health Services. Data were obtained using structured observation of participants in their working environment, with the creation of field notes, complemented by analysis of documented patient records. An example of this was observation of the process used in dressing changes, the time of day it was undertaken and how and when such data were recorded for future assessment. Statistical analyses of data were undertaken by comparing means, correlations, and appropriate statistical significance tests (Mann–Whitney U‐Test, Kruskal–Wallis test, Pearson correlation coefficient). The accepted level of statistical significance was α = 0·05.

Ethical considerations

The research met the ethical principles for research involving human subjects (in accordance with the Helsinki declaration of 1975 as revised in 2000) and was approved by the management of involved health care facilities and institutional Ethics Committees. It was not considered necessary to obtain written consent from each patient because of the nature of the study, but participation was entirely voluntary and could be withdrawn at any time during the survey.

Results

Of the 187 health care facilities across the Czech Republic that were invited to participate, an analysis was carried out in 77 (41%)), after consent was given by their managements (8 university/faculty hospitals, 63 hospitals and 6 long‐term hospitals. A cross‐section of work places from all regions of the Czech Republic was represented. The largest number of participating health facilities were from the South Moravian region (n = 15). The least involved health care facilities were from the Highland (n = 1) and Karlovy Vary regions (n = 2). The investigation, using all planned research methods, was implemented in 95 departments/nursing units. More workplaces were included, because they had an inconsistency in their evaluation procedures. One unit in 64 hospitals, two units in 8 hospitals (n = 16) and three units in 5 (n = 15) hospitals with the most different assessment methods were visited. The survey was conducted separately in internal medicine (25%) and surgical wards (34%). Other hospital units were evaluated (28%) and the remaining units provided care for long‐term patients (13%).

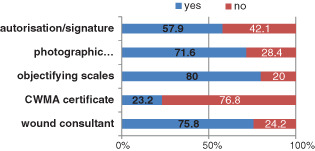

Figure 1 shows the information collected on wound management organisation. The majority of the units studied had a nurse (authorised person) working as a wound consultant (76%) using objective scales for the evaluation of overall patient health status (80%). The Barthel index for basic daily activities, the Mini Nutritional Assessment and the Mini Mental State Examination were the most commonly used scales. Wound care certification offered by CWA had been awarded to 22 units, out of the 95 in total (23%). Photographic documentation was conducted at a majority of the units (72%), but the quality was poor. This was related to a lack of standard operating procedures for the use of a specific digital camera with instructions on lighting, distance and focusing. As a consequence, photographs were not adequate to be a useful adjunct to wound progress as even wound measurements could not be taken. However, there was a problem with the process of data concealment. A more detailed recording of the monitored parameters of non‐healing, chronic wounds was performed mostly in nursing documentation (95%). Surprisingly, this information was missing in the medical records, a common practice for most of the units involved in long‐term care, and was recorded only as the occurrence of a wound (e.g. pressure ulcer) and treated according to the protocol. Another important finding was that only at 55 (58%) workplaces, the person who recorded information was authorised to use the required signature or official stamp set by legislation.

Figure 1.

Wound management organisation.

Observation of the basic/fundamental wound parameters

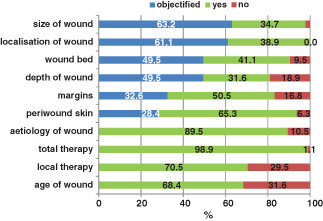

Figure 2 summarises the records of basic/fundamental parameters of wounds. The figure lists the parameters of wounds reported in descending order (from top to bottom) with the use of objective scales. The size and localisation of wounds were the most commonly evaluated and reported parameters.

Figure 2.

Basic/fundamental wound parameters – objectification.

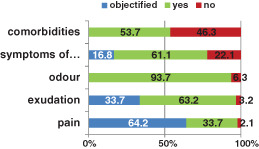

In Figure 3, pain is shown to be the most common objectively specific parameter (66%). Odour was not recorded using any scales, and nurses described and named odour in their own language and terms very subjectively.

Figure 3.

Specific wound parameters – objectification.

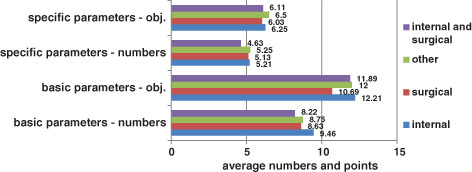

On the basis of data obtained on the assessment of basic and specific wound parameters, the quality of assessment was also sought and recognised. The type of hospital accreditation [national, international, e.g. Joint Commission Accreditation (JCI) or International Organisation for Standardisation (ISO) certification] was studied and no statistically significant differences were found (P ≥ 0·5). Another assumption was that in the faculty hospitals, the process of evaluation would be at a better level, but again no statistically significant differences were found (P ≥ 0·5). The type of specialisation of a unit was confirmed as being important in relation to the assessed number of basic wound parameters (P = 0·036). At internal units, more basic parameters were assessed and reported, but they did not use objective scales more commonly than did surgical units (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Assessment according to the type of unit.

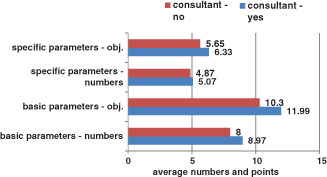

The presence of a nurse consultant for wound healing was found to significantly affect wound assessment in the objectification of basic wound parameters (P = 0·047; Figure 5). As expected, it had to be acknowledged that when the consultant was present, the process of wound evaluation was better and of a higher quality. The same applies to the units awarded certification by the CWA (P = 0·010). The scope of the assessment parameters of non‐healing, chronic wounds was also verified as being statistically significant, and as being dependent on the interest of workplaces to create a wound assessment tool in the field of basic wound parameters – objective recording (P = 0·032) as well as specific parameters of the wounds (P = 0·031).

Figure 5.

Assessment according to the presence of wound consultant.

Further analysis of the findings related to individual wound parameters (wound bed, exudate, odour and pain) is discussed in the following section.

Discussion

The results of this study have shown that there is inconsistency in the process of wound assessment among health care facilities in the Czech Republic. This discussion includes only the data that were most important with respect to everyday nursing clinical practice. Many of the remaining data were of inconsistent quality and would not have added value to changes in practice. It has been recognised that the assessment of wound parameters depends on the presence of wound consultants at the workplace – on the assumption that they are more experienced and able to assess wounds more accurately. This confirms the results of the study conducted by Cook 26, which related the level of education in the evaluation and documentation of wounds to the quality of the care process. So far, there has been a lack of studies focusing on the knowledge and skills of nurses in the evaluation of non‐healing, chronic wounds. With regard to the level of their knowledge, nurses need support, particularly in relation to acceptance of their knowledge and competencies by the team 14. Other published surveys have highlighted deficiencies in the use of objective practices such as scales and maps 3, 14, 27, 28. It was recognised that wound, localisation, wound depth and wound bed were the basic parameters most commonly assessed in the wound. Correct wound measurement helps nurses to identify whether a wound is healing or not 29, 30, 31. It has been acknowledged that measurements carried out by nurses in daily clinical practice lack precision, mostly because nurses are short of time. However, in this study, 63% of hospital nurses were found to be using disposable rulers for measuring wound size, which is consistent with the findings presented in some other sources that it is the most common way of measurement 14, 32, 33. In the rest of the hospitals evaluated where wound size was measured (35%), nurses compared the size of the wound with everyday objects (e.g. a matchbox) or it was estimated by eye, which is not appropriate. A possible solution could be the use of good quality photography or photogrammetric software, which could save time and simultaneously provide accurate information for storage 17, 34, 35, 36, particularly with regard to irregularly shaped wounds. The current economic situation in most Czech hospitals precludes this possibility and, therefore, measurement with disposable rulers is considered as the gold standard for calculation of the wound volume 32, 33. This process is probably effective and sufficiently accurate in day‐to‐day care but not in research studies.

Objective assessment of the wound bed was carried out using the wound healing continuum (WHC) definitions 30, 37, 38, 39 in 49·5% of hospitals, with the wound bed being described as necrotic (black), sloughy (yellow), granulating (red) and epithelialising (pink) corresponding to supporting expert advice. On further analysis of the documents, it was found that only the basic wound bed tissue types were recorded, whereas the transitional type of wound beds were rated at only two workplaces. A relatively high percentage of the use of grading scales was also influenced by the strategies of distributors of wound healing materials who have prepared an overview of product portfolios and their use for the healing stage according to WHC and TIME systems. Nurses who were not familiar with any objective scales described the tissue of the wound bed in their own words, which was confirmed in Cook's survey of general nurses who were not familiar with these tools 26, but according to the findings of this study, nurses were better in the evaluation of WHC than doctors. In another survey from the Netherlands, it was found that the knowledge of 63 nurses and 79 doctors was consistent 40, and an Austrian study published in the same year verified that evaluation errors occur in both groups 41. These were least often found in the assessment and monitoring of the wound edges (n = 31, 32·6%) and surrounding skin (n = 27, 28·4%). The field notes from observations, and subsequent analysis of patients' documentation, showed that even if an objective assessment was made locally using an applicable scale, nurses used terms that do not have the same meaning. Nurses often did not use pre‐defined terms, and the description of the edges and surrounding skin area corresponded to the comments written in their own words. Procedures in which uniform terminology is not used pose a risk of misconduct and disrupt the continuity of care. This issue of the use of jargon, acronyms and typing errors has been recognised and addressed by others 42, 43.

The follow‐up phase of the research was to assess the evaluation and recording of specific parameters of wounds in clinical practice. These are the parameters that are not always evaluated by a nurse or when a decision (such as assessment of contamination or colonisation) does not fall within a nurse's competence. Assessment of specific parameters requires a certain level of experience and sufficient theoretical knowledge of the anatomy and pathophysiology of the skin and the skin's healing process. A microbiological swab of each wound was taken in all patients, in all workplaces, although it is known that this is not indicated. This common practice has to be changed as the yield of such ‘routine’ testing is rarely conducive to effective therapy and may increase the use of inappropriate antibiotic therapy. Statistical analysis of this indiscriminate use of swabs was therefore, not undertaken. The most commonly assessed specific parameter of non‐healing wounds was odour (n = 89; 94% of workplaces), which is rarely considered in wound trials. It is a logical assumption that all wounds produce odour. Healthy wounds have a slight, but not unpleasant, odour like fresh blood 44. An increasing intensity of the odour, or an unexpected change, might be an important signal of a sudden deterioration in the healing process 44. Although it was not expected that odour would be evaluated according to a scale, five workplaces were identified where as many as 34 descriptors of odour were recorded. However, only four of them matched the characteristics described by expert sources 45. Interestingly, odour assessment is included in national guidelines from Ireland and Australia, which recommend an assessment of the occurrence of odour during care – no odour, odour in intact primary dressing, odour when removing the dressing, or odour upon entering the room 46, 47. Odour and increasing exudate are two symptoms that distress patients the most, triggering anxiety about the resultant poor quality of life, especially in those with fungating wounds 48. Odour should not be underestimated, and should be evaluated appropriately.

Low amounts of exudate are normal in wound healing and are responsible for maintaining the moist wound environment considered necessary for optimal healing. Whilst it is normal for a wound to produce haemoserous exudate during the healing process, an increase in exudate volume or viscosity may indicate infection or impeding dehiscence 49, 50. From the analysis of document content, it was found that nurses usually assessed exudate character according to a colour scale, usually expressed using a variety of technical terms – serous, haemoserous, purulent. Nurses examined the nature of exudate with regard to dressing types at only three workplaces, out of a total of 95 facilities, but none corresponded to best practice. The field notes showed that nurses believed that the evaluation of exudate should be the doctor's responsibility, but a doctor may not be present at each dressing change of non‐healing wounds. In this context, Cook 26 drew attention to the belief held by nurses that an exact evaluation of the wound using scales is highly time consuming and not possible in their day‐to‐day work management. Therefore, it was recommended that an assessment should be made with simple pictograms to indicate the extent of exudate, which would be similar to the colour range for the WHC. For evaluating exudates, the wound exudate continuum (WEC) definitions could be used effectively, which is a guideline for the choice of therapeutic material for the absorption or, conversely, the retention of moisture in the wound 51.

The last specific parameter of the survey was the evaluation of pain. Pain was the most extensively evaluated specific parameter of chronic wounds. In 64% of workplaces, pain evaluation was undertaken through the use of an objective rating scale. However, the participants' observations showed that the assessment of pain was not usually a common part of the recorded progress of non‐healing, chronic wounds. Pain was not always associated with the wound but rather with the general status of the patient. Evaluation was predominantly focused on pain intensity and carried out with the use of a visual analogue scale (VAS). Pain status or pain associated with nursing interventions (such as pain at dressing changes) was not assessed. This corresponds to the findings in an earlier study involving 250 Czech nurses 52. McCluskey and McCarthy showed in their study that the majority (81%) of respondents assessed pain routinely 14. The assessment of pain is important for several reasons: it distresses patients 37, 53, 54; an increase in pain may indicate infection 55; and it may relate to delayed healing. A prolonged inflammatory response stimulates the local afferent skin receptors (nociceptive) or peripheral nerve endings with increased sensitivity or hyperalgesia 37, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57. Hence, on‐going assessment and team communication are essential for effective pain management 58.

In this study, it was confirmed that weaknesses exist in wound assessment in current nursing practice in the Czech Republic. The management of all involved hospitals was acquainted with the results of the survey and it was clear that they were interested in removing the highlighted shortcomings of care. Almost all of the 77 hospitals (n = 62; 80%) were interested in the publication of a wound assessment guide. More than half (60%) of the hospital managers were interested in online consulting and 52% of them wanted to be involved in the process of preparation of ‘tailored’ recording for wound care and wound assessment (a wound assessment guide). The results from other surveys also show that there is limited acceptance of nurses' knowledge and skills in the team, and not only in relation to wound management 14, 19, 26, 41. The introduction of easy‐to‐use, validated wound assessment tools would help inexperienced nursing staff in orientation and decision making and can serve as an aide‐memoire for experienced nurses 59.

Conclusions and recommendations

Many nurses, not only in the Czech Republic, lack knowledge regarding wound management and wound assessment skills. Any wound assessment tool has to be clear and simple and should provide support for nurses working in this area. Hard‐to‐heal, chronic wounds require more nursing time and additional resources. If a nurse was able to recognise the primary symptoms of delayed healing, he or she could take action with early intervention. From the analysis of this study, it was found that the evaluation process of non‐healing, chronic wounds in selected Czech health care facilities was not homogeneous. It was shown that nurses are not using objective techniques and tools for the evaluation of the basic and specific parameters of wounds. One of the main reasons for this is the lack of unified recommendations – guidelines for the evaluation of non‐healing wounds in clinical practice at the national level. In collaboration with CWA, the Clinical Wound Assessment Algorithm was prepared 60. The algorithm was compiled through the process of adaptation after an analysis of the available published best practices, in the form of expert‐recommended procedures (an opinion‐based guideline) to produce the AGREE II tool (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation) 61 and the ADAPTE tool for transcultural adoption 62. The algorithm was disseminated to the involved hospitals as an electronic publication and it will be published as a supplement to the Czech scientific journal Wound Healing. The first year pilot project will be completed by the end of summer 2014. The process of implementation of the algorithm is developed through educational activities in the individual health care facilities through a domino effect. The Ministry of Health will publish the final version of the algorithm on their website and the use of the algorithm will be one of the indicators of quality of care for patients with non‐healing, chronic wounds. A reassessment of the algorithm is planned after one year of its use, with another study focused on the evaluation process of non‐healing, chronic wounds and the efficiency of a uniform procedure for evaluation.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the managers of the involved health care facilities for their collaboration and also the committee members of Czech Wound Management Association (CWMA) for their support during the preparation of the clinical algorithm and their review of this manuscript. The research was conducted as a part of the project – Preparation and implementation of recommended nursing process in the care of patients with non‐healing wound – objectifying diagnostics MUNI/A/0948/2013.

We have no conflicts of interest with any financial organisation regarding the material discussed in the manuscript.

References

- 1. Bates‐Jenson BM, Sussman C. Wound care: a collaborative practice manual for physical therapists and nurses. Gaithersburg: Aspen Publishers, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Russell L. The importance of wound documentation and classification. In: White R, editor. Trends in wound care. Bath: Mark Allen Publishing, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ousey K, Cook L. Understanding the importance of holistic wound assessment. Pract Nurs 2011;22:308–14. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bradbury S, Ivins N, Harding K. Case series evaluation of a silver non‐adherent dressing. Wounds UK 2011;7:12–9. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lafferty B, Wood L, Davis P. Improved care and reduced costs with advanced wound dressings. Wounds UK 2011;7:14–23. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gottrup F, Apelqvist J, Bjansholt T, Cooper R, Moore Z, Peters EJG, Probst S. EWMA document: antimicrobials and non‐healing wounds – evidence, controversies and suggestions. J Wound Care 2013;22(5 Suppl):4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hjort A, Gottrup F. Cost of wound treatment to increase significantly in Denmark over the next decade. J Wound Care 2010;19:173–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Posnett J, Gottrup F, Lundgren H, Saal G. The resource impact of wounds on health‐care providers in Europe. J Wound Care 2009;18:154–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pokorná A. Možnosti vzdělávání sester v oblasti chronických ran na univerzitní půdě (in Czech). Hojení ran 2008;2:32–3. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pokorná A. Nové trendy ve výuce sester k získání zvláštní odborné způsobilosti k péči o chronické rány a defekty (in Czech). Sestra 2009;19:52. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Timmons J. Wound care education needs a boost. Br J Community Nurs 2006;11(Suppl):S3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ashton J, Price P. Survey comparing clinicians' wound healing knowledge and practice. Br J Nurs 2006;15(Suppl):18S–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Haram R, Ribu E, Rustøen T. The views of district nurses on their level of knowledge about the treatment of leg and foot ulcers. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2003;30:25–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. McCluskey P, McCarthy G. Nurses' knowledge and competence in wound management. Wounds UK 2012;8:37–47. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Leaper D. Evidence‐based wound care in the UK. Int Wound J 2009;6:89–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Worley C. Assessment and terminology: critical issues in wound care. Dermatol Nurs 2004;16 451–452, 457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Keast DH, Bowering CK, Evans AW, MacKean GL, Burrows C, D'Souza L. MEASURE: a proposed assessment framework for developing best practice recommendations for wound assessment. Wound Repair Regen 2004;12:S1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schultz GS, Sibbald RG, Falanga V, Ayello EA, Dowsett C, Harding K, Romanelli M, Stacey MC, Teot L, Vanscheidt W. Wound bed preparation: a systematic approach to wound management. Wound Repair Regen 2003;11(1 Suppl):S1–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ousey K, Cook L. Wound assessment: made easy. Wounds UK 2012;8:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schultz GS, Barillo DJ, Mozingo DW, Chin GA. Wound bed preparation and a brief history of TIME. Int Wound J 2004;1:19–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Keast DH, Bowering CK, Evans AW, Mackean GL, Burrows C, D'Souza L. MEASURE: a proposed assessment framework for developing best practice recommendations for wound assessment. Wound Repair Regen 2004;12(3 Suppl):S1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Leaper DJ, Schultz G, Carville K, Fletcher F, Swanson T, Drake R. Extending the TIME concept: what have we learned in the past 10 years? Int Wound J 2012;9(2 Suppl):1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Creswel JW, Plano Clark VL. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. London: Sage, 2007:5. [Google Scholar]

- 24. McKie L. Engagement and evaluation in qualitative inquiry. In: May T, editor. Qualitative research in action. London: Sage, 2002:261–85. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Žiaková K. Ošetrovateľstvo, teória a vedecký výskum(in Slovak). Martin: Osveta, 2009:168–9. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cook L. Wound assessment: exploring competency and current practice. Br J Community Nurs 2011;16:40. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hollinworth H, Taylor D, Dyble T. An educational partnership to enhance evidence‐based wound care. Br J Nurs 2008;7:13–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sabasse M, Ruba R. The role of a structured educational programme in enhancing the knowledge of nurses in wound assessment and documentation. EWMA J 2013;3:42. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Little C, McDonald J, Jenkins MG, McCarron P. An overview of techniques used to measure wound area and volume. J Wound Care 2009;18:250–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dowsett C. Using the TIME framework in wound bed preparation. Br J Community Nurs 2008;13:S15–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hanson D, Langemo D, Anderson J, Hunter S, Thompson P. Measuring wounds. Nursing 2007;37:18–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Langemo DK, Melland H, Olson B. Comparison of 2 wound volume measurement methods. Adv Skin Wound Care 2001;14:190–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Langemo DK, Anderson J, Hanson D. Measuring wound length width and area. Adv Skin Wound Care 2008;21:42–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gethin G. The importance of continuous wound measuring. Wounds UK 2006;2:60–8. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Harding K. Methods for assessing change in ulcer status. Adv Wound Care 1995;8(4 Suppl):37–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Romanelli M. Technological advances in wound bed measurements. Wounds 2002;14:58–66. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Eagle M. Wound assessment: the patient and the wound. Wound Essent 2009;4:14–24. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gray D, White RJ, Cooper P. The wound healing continuum. Br J Community Nurs 2002;7(12 Suppl 13):15–9.11823726 [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gray D, White R, Cooper P, Kingsley A. Using the wound healing continuum to identify treatment objectives. Wounds UK 2005;1:9–10. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Vermeulen H, Ubbink DT, Schreuder SM, Lubbers MJ. Inter‐ and intra‐observer (dis)agreement among nurses and doctors to classify colour and exudation of open surgical wounds according to the Red‐Yellow‐Black scheme. J Clin Nurs 2007;16:1270–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Stremitzer S, Wild T, Hoelzenbein T. How precise is the evaluation of chronic wounds by health care professionals? Int Wound J 2007;4:142–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Danielsson‐Ojala R, Lundgren‐Laine H, Salanterä S. Describing the sublanguage of wound care in an adult ICU. Stud Health Technol Inform 2012;180:1093–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Urquhart C, Currell R, Grant MJ, Hardiker NR. Nursing record systems: effects on nursing practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;21:1–66. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002099.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cutting K, Harding KG. Criteria for identifying wound infection. J Wound Care 1994;3:198–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Fleck CA. Palliative dilemmas: wound odour. Wound Care Can 2006;4:10–4. [Google Scholar]

- 46. AWMA – Australian Wound Management Association . Standards for wound management, 2nd edn. West Leederville: Cambridge Publishing, 2010:10. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Health Service Executive . National Best Practice and evidence based guidelines for wound management. Dublin: Health Service Executive, 2009. 30, 64. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lund‐Nielsen B, Miller K, Adamsen L. Malignant wound in women with breast cancer: feminine and sexual perspectives. J Clin Nurs 2005;14:56–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mulder GD. Quantifying wound fluids for the clinician and researcher. Ostomy Wound Manage 1994;40:66–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Thompson G, Stehen‐Haynes J. An overview of wound healing and exudate management. Br J Community Nurs 2007;12:S22–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. World Union of Wound Healing Societies (WUWHS) . Principles of best practice: wound exudate and the role of dressing. A concensus document. London: MEP Ltd, 2007:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Pokorna A, Koutna M. Pain management regarding non‐healing wounds from nurses viewpoint. EWMA J 2013;3:87. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Solowiej K, Mason V, Upton D. Review of the relationship between stress and wound healing: part 1. J Wound Care 2009;18:357–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Solowiej K, Mason V, Upton D. Assessing and managing psychological stress and pain in wound care, part 2: pain and stress assessment. J Wound Care 2010;19:57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Augustin M, Maier K. Psychosomatic aspects of chronic wounds. Dermatol Psychosom 2003;4:5–13. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Solowiej K, Mason V, Upton D. Psychological stress and pain in wound care, part 3: management. J Wound Care 2010;19:153–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Evans E, Gray M. Do topical analgesic reduce pain associated with wound dressing changes or debridement of chronic wound? J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2005;32:287–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Price P, Fogh K, Glynn C, Krasnes DL, Osterbrink J, Sibbald RG. Managing painful chronic wounds: the wound pain management model. Int J Wound 2007;1(4 Suppl):4–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Padmore J. The introduction and evaluation of applied wound management in nurse education. In: Applied wound management part 3. Aberdeen: Wounds UK, 2009:28–30. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Pokorna A. Klinický algoritmus pro hodnocení nehojící se rány. Brno: NCONZO, 2014:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Brouwers M, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Zitzelsberger L, For the AGREE Next Steps Consortium . AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in healthcare. Can Med Assoc J 2010;182:E839–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Fervers B, Burgers JS, Voellinger R, Brouwer S, Browman GP, Graham ID, Harrison MB, Latreille J, Mlika‐Cabane N, Paquet L, Zitzelsberger L, Burnand B. Guideline adaptation: an approach to enhance efficiency in guideline development and improve utilisation. BMJ Qual Saf 2011;20:228–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]