Abstract

In chronic wound management, alginate dressings are used to absorb exudate and reduce the microbial burden. Silver alginate offers the added benefit of an additional antimicrobial pressure on contaminating microorganisms. This present study compares the antimicrobial activity of a RESTORE silver alginate dressing with a silver‐free control dressing using a combination of in vitro culture and imaging techniques. The wound pathogens examined included Candida albicans, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, β‐haemolytic Streptococcus, and strictly anaerobic bacteria. The antimicrobial efficacy of the dressings was assessed using log10 reduction and 13‐day corrected zone of inhibition (CZOI) time‐course assays. Confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) was used to visualise the relative proportions of live/dead microorganisms sequestered into the dressings over 24 hours and estimate the comparative speed of kill. The RESTORE silver alginate dressing showed significantly greater log10 reductions and CZOIs for all microorganisms compared with the control, indicating the antimicrobial effect of ionic silver. Antimicrobial activity was evident against all test organisms for up to 5 days and, in some cases, up to 12 days following an on‐going microbial challenge. Imaging bacteria sequestered in the silver‐free dressing showed that each microbial species aggregated in the dressing and remained viable for more than 20 hours. Growth was not observed inside of the dressing, indicating a possible microbiostatic effect of the alginate fibres. In comparison, organisms in the RESTORE silver alginate dressing were seen to lose viability at a considerably greater rate. After 16 hours of contact with the RESTORE silver alginate dressing, >90% of cells of all bacteria and yeast were no longer viable. In conclusion, collectively, the data highlights the rapid speed of kill and antimicrobial suitability of this RESTORE silver alginate dressing on wound isolates and highlights its overwhelming ability to manage a microbial wound bioburden in the management of infected wounds.

Keywords: Alginate, Bacteria, Confocal, Silver

INTRODUCTION

Microorganisms are present in all chronic wounds, including those that do not exhibit obvious signs of clinical infection (1). Contamination of a wound can involve the presence of a low level of microorganisms that are able to persist in the wound environment. In contrast, colonisation of wounds involves the presence of multiplying bacteria, although an associated host reaction may not be observed (2). On occasion, the presence of microorganisms in wounds, such as in the case of infection, is considered to be a contributing factor to delayed wound healing (3). Such chronic wounds are a major problem in developed countries, with an estimated 2–3% of the population suffering from them at some point in their lives (4). In addition to increased patient morbidity associated with chronic wounds, there is also a considerable financial cost to healthcare providers, with an estimated annual expenditure of $25 billion associated with chronic wound care in the USA alone (5).

The causes of chronic wounds are multiple, often involving underlying peripheral vascular diseases, uncontrolled diabetes, or prolonged pressure ulceration (6). In recent years, much attention has focussed on the role that microorganisms play in impairing wound healing (7) which could arise through the promotion of continuous inflammatory responses or the presence of microbial virulence factors that induce damage to the local tissue (8). For example, during wound infection, the number and virulence of infecting organisms are sufficient to overcome host defence mechanisms, thereby causing tissue damage and delayed healing.

Some researchers have postulated the concept of a ‘critical colonisation’ of wounds, which implies that at a given bioburden of microorganisms (i.e. 105 colony forming units (CFU) per gram of wound tissue) delayed healing is induced (9). This concept does not, however, take into consideration wound aetiology, the type of microbial species present, nor their relative virulence potential (1). In addition, there is increasing evidence to suggest that there is no direct correlation between wound bioburden and non healing in chronic wounds 7, 10. Indeed, it seems more likely that synergy between bacteria present, producing enhanced virulence, is a significant contributing factor to non healing 7, 11. Also, it has more recently been reported that microbial colonisation of wounds involves the formation of polymicrobial biofilms 12, 13. Biofilms can be defined as communities of microorganisms, invariably attached to a solid surface, and encased within an extracellular polymeric substance, generated by the microorganisms themselves. Importantly, it has been shown that biofilms exhibit a much higher tolerance to both host immune defences, as well as to any administered antimicrobial agents 14, 15.

To combat infection and wound biofilms, a number of strategies have been utilised. Topical antimicrobials including certain antibiotics, antiseptics and disinfectants have all been used with varying degrees of success. Povidone iodine is an antiseptic that has Food and Drug Administration approval for use on certain types of superficial and acute wounds (16). Topical antibiotics may eliminate surface bacteria and those not associated with the biofilm. Generally however, these topical agents are not deemed effective in the complete eradication of biofilms. Furthermore, prolonged use of topical antibiotics can potentially provide a selective pressure for bacterial resistance against the administered agent (17). Systemic antibiotic therapy is more frequently used for treating chronic wounds, although limited evidence on the effectiveness of such therapies on promoting wound healing exists 18, 19. Frequent physical debridement of microbial biofilms can, at least in part, reduce the biofilm in wounds to levels that may be sensitive to administered antimicrobial agents (20).

A wide range of wound dressings are available to promote wound healing through the generation and maintenance of a moist environment. The types of dressings frequently used include low adherent dressings suitable for flat exudating wounds, semi‐permeable flexible films for use at anatomically difficult sites, as well as hydrocolloid dressings, hydrogels, foams and alginates (21) which swell in the presence of moisture to fill the wound site. In addition, a number of antimicrobial dressings are also available that are often impregnated with agents such as iodine, silver or metronidazole gels. The use of silver dressings has widely been promoted as a means of reducing the bioburden of wounds without concomitant development of resistant bacterial strains (22) and preventing a wound infection (23). Silver alginate dressings in particular are known to have prolonged antimicrobial efficacy, sometimes as long as 21 days, indicating sustained availability of ionic silver and therefore the requirement of fewer dressings changes (24). Metallic silver is inert, but will release silver ions in an aqueous environment. It is these silver ions that exhibit antimicrobial effects through first absorption and then concentration within microbial cells. Inside the microbial cell, ionic silver denatures proteins, and also binds to nucleic acids, thus inhibiting protein function and cell replication. Ionic silver exhibits activity against a wide spectrum of microorganisms, although the extent of activity varies depending upon the ionic form used, and also the possible interaction with complex organic molecules in the surrounding medium. Few studies have looked at the development of silver resistance following long term use of such dressings.

This present study aimed to examine the antimicrobial properties of one such silver alginate dressing (RESTORE silver alginate) against typical wound microorganisms. This activity was compared with an equivalent silver‐free alginate control dressing (silver‐free alginate). In addition to determining antimicrobial activity over time using log10 reduction and corrected zones of inhibition (CZOIs), a direct analysis of antimicrobial activity within the dressings was performed using live/dead‐staining and CLSM of microorganisms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Microorganisms and test dressings

Test dressings were RESTORE silver alginate (Holister Woundcare, Libertyville, IL, USA) and a silver‐free alginate (Advanced Medical Solutions Ltd., Winsford, UK). A total of nine microbial strains were used to assess the antimicrobial activity of the dressings (Figure 1). All aerobic species were subcultured at 24 hours intervals and maintained at 37°C using Mueller–Hinton agar (MHA) and Mueller–Hinton broth (MHB). Strict anaerobic bacterial strains were cultured on fastidious anaerobe agar (FAA) supplemented with 5% (v/v) defibrinated horse blood (TCS Biosciences Ltd., Buckingham, UK) and in Brain–Heart Infusion broth (BHI). These anaerobic bacteria were cultured for 48 hours at 36–37°C in an anaerobic environment (10% v/v CO2, 20% v/v H2, 70% v/v N2). All media, unless otherwise stated, was obtained from Lab M™ (International Diagnostics Group plc, Bury, UK).

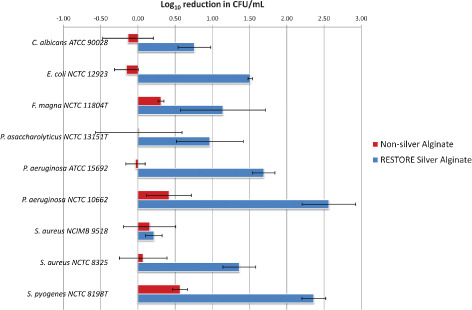

Figure 1.

Log10 reduction assay measuring dressing antimicrobial activity after 2 hours exposure (n = 3; standard deviation from the mean was used to produce the error bars).

Log10 reduction assay to measure antimicrobial efficacy (speed of kill)

The ability of the dressings to rapidly kill microorganisms was determined using a one‐day log10 reduction assay adapted from Cavanagh et al. (25). Colonies from agar cultures were used to inoculate 20 ml of liquid medium, which was incubated for either 24 hours for aerobes or 48 hours for anaerobes, and then a portion of this culture (100 µl) was used to inoculate a fresh 20 ml liquid culture. The re‐inoculated media was incubated under the same conditions, either 4–6 hours for aerobes, or 36–48 hours for anaerobes, until the organism was in log‐phase growth and contained approximately 108 CFU/ml.

Test dressings were aseptically cut into 2 cm2 pieces. The experimental dressing pieces were then immersed in sterile phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and allowed to saturate during 1 hour incubation in the dark, at room temperature. Control dressing pieces were similarly immersed in neutralisation buffer (NB), which inactivates ionic silver. NB consisted of PBS containing 1% (v/v) polysorbate 20 and 0·1% (w/v) sodium thioglycolate (Sigma‐Aldrich Ltd., Gillingham, UK).

Saturated dressings were aseptically transferred, without squeezing, and allowed to drain for 10 seconds before being placed flat in a sterile container. Each dressing was then inoculated with 1 ml of the log‐phase culture and incubated, in the dark and under the appropriate conditions, at 37°C for 2 hours. Following incubation, dressings were placed in NB (9 ml) to achieve a 1:10 dilution of the inoculum and vigorously vortexed for 10 seconds to re‐suspend the microbial cells. The recovered microorganisms were then serially diluted in NB. Each dilution (50 µl) was spirally plated on to appropriate agar media using a Whitley Automatic Spiral Plater (WASP; Don Whitley Scientific Ltd., West Yorkshire, UK) and plates incubated either overnight for aerobes or for 48 hours for anaerobes. Subsequently, the resulting number of colonies was counted to calculate the number of CFUs from each dressing. The counts generated from the neutralised control dressing pieces were used to estimate initial microbial numbers CFU/ml in the original inocula, while the counts from the experimental dressing pieces were used to calculate the surviving number of CFU/ml. Log10 reduction values, representing the antimicrobial effect of the dressing were then calculated as the difference between the log10 values of the starting and surviving numbers of microorganisms.

CZOI assay to assess antimicrobial persistence of the wound dressings

The ability of the dressing to inhibit microbial growth over several days was also assessed using a day‐to‐day agar transfer and CZOI assay, adapted from Cavanagh et al. (25).

Fresh culture of each test microorganism (100 µl) was used to create a microbial lawn on agar, as per the The British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy guidelines for disc diffusion testing (26). Triplicate pieces of the test dressing (2 cm2) were saturated with sterile distilled water and aseptically placed on to the middle of the seeded agar plates. Prior to placement on the agar, the dressings were allowed to drain for approximately 10 seconds. The original placement of the dressing pieces was traced on to the base of the petri plate to allow correction for any dressing shrinkage over time. Plates were incubated with the dressing, either overnight for aerobic species or for 48 hours for anaerobes. The dressings were then transferred to a new agar plate, seeded as above, and incubated in the same manner. The zones of microbial growth inhibition and original dressing widths were measured in two perpendicular directions for each plate. These measurements were then used to calculate the CZOI value by dividing the inhibition zone width by the dressing width. This procedure was repeated for each microorganism for as many days that were required for all the dressing pieces to no longer inhibit growth.

CLSM to visualise death of sequestered microorganisms

Broth cultures of Candida albicans ATCC 90028, Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 15692 and Staphylococcus aureus NCTC 8325 were cultured in a shaking incubator until mid‐log phase growth, for 5–6 hours. Each culture (5 ml) was briefly centrifuged (13 000 g, 1 minute), the media gently aspirated, and the pellet of cells re‐suspended in PBS (1·5 ml) containing working concentrations of live/dead BacLight™ bacterial viability kit (Invitrogen Molecular Probes Inc., Eugene, OR). The stained microbial suspensions (100 µl) were pipetted on to fibres from each dressing, on glass slides with a cover slip sealed with petroleum jelly to prevent drying out. Preparations were viewed and analysed using a Leica TCS SP2 spectral confocal microscope and Leica confocal software (Leica, Heidelberg, Germany). Representative regions of dressing were scanned through their full depth at 20‐minute intervals over a 15 hour period using a ×20 objective lens and appropriate scan parameters for simultaneous fluorescence recordings of live cells (Syto 9; green fluorescence; excitation filter (Ex) maximum 485 nm; emission filter (Em) maximum 500 nm) and dead cells (propidium iodide; red fluorescence; Ex maximum 536 nm; Em maximum 617 nm). The excitation lasers used for each probe (argon 488 nm and helium neon 543 nm, respectively) were used at their lowest possible power output to minimise potential phototoxic side‐effects on the microorganisms. To provide context, individual fibres within the dressing were simultaneously imaged using Nomarski differential interference contrast (DIC) optics. Z‐Stacks of optical sections taken at each time point were reconstructed using a maximum intensity projection algorithm and then presented as green/red bacterial overlays upon a greyscale DIC image of the fibres. Bacterial viability curves were produced from analysing the relative ratio of representative green/red (live/dead) fluorescent signal intensities (i.e. voxel intensities 0–255) at each time point from within selected regions of interest.

RESULTS

Log10 reduction assays to measure antimicrobial efficacy

Compared with the silver‐free dressing, the log10 reduction assays showed excellent antimicrobial activity with the RESTORE silver alginate dressing (Figure 1). No growth inhibition was evident using RESTORE silver alginate dressing previously immersed in NB. While all bacterial species tested were inhibited by ionic silver, this was in a strain dependent manner. In addition, distinct differences were seen between different isolates of the same species for example, S. aureus. Antifungal activity was similarly evident against the tested C. albicans strain. P. aeruginosa exhibited greatest sensitivity to the silver dressing, with Streptococcus pyogenes and Escherichia coli also appearing particularly sensitive. In contrast, S. aureus NCIMB 9518 exhibited greater tolerance to the silver containing dressing.

CZOI assay to assess antimicrobial persistence of silver dressings

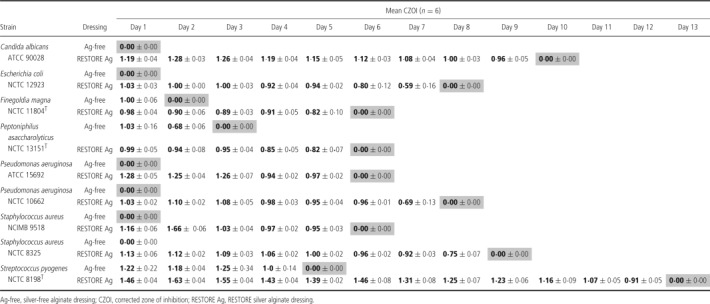

Confirmation of the persistence of antimicrobial activity of the silver containing dressings was provided by the CZOI assay (Table 1). Strain‐dependent variation was again apparent, but the RESTORE silver alginate dressing was able to produce a clearance zone for up to 5 days for each strain tested.

Table 1.

CZOI assay to measure antimicrobial longevity of wound dressings

CLSM to visualise death of sequestered microorganisms

When the dressings were hydrated with stained microbial culture, the alginate fibres swelled quickly, causing sequestration and immobilisation of the microorganisms in the gel‐like spaces between the fibres. With the silver‐free dressing, all microbial species quickly formed aggregates of viable cells. Bacterial multiplication was not evident, indicating a possible microbiostatic effect inherent to this alginate dressing. In comparison, when the same organisms were added to the RESTORE silver alginate dressing, they progressively appeared red (i.e. dead) with some red cells evident within the first hour indicating a rapid speed of kill evident in real time. Figure 2 shows the rapid kill observed for both P. aeruginosa and S. aureus within the RESTORE silver alginate dressing. In the case of P. aeruginosa, total kill of the microbial bioburden in the dressing was evident within 16 hours, whereas for the S. aureus microbial load, 4 hours was sufficient time for a total cidal effect to be observed. The broad‐spectrum antimicrobial effect of silver was evident when C. albicans was exposed to the dressing fibres.

Figure 2.

Confocal laser scanning microscopy images of live/dead stained microorganisms on alginate dressing fibres.

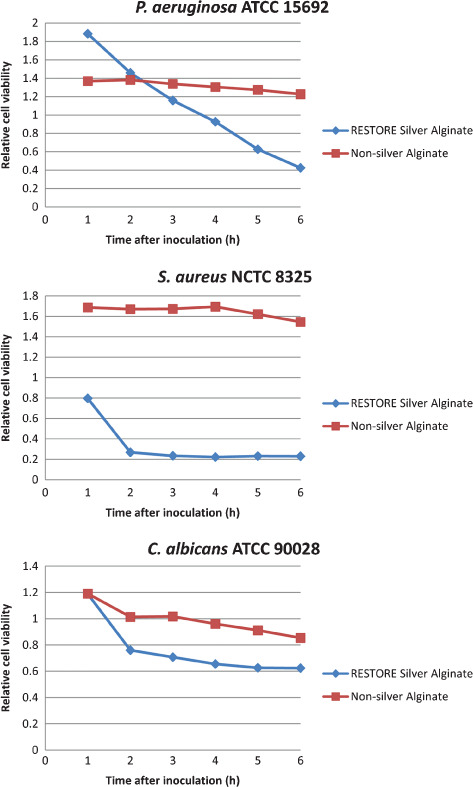

An estimate of the relative viability of microbial cells at each time point could be made by comparing the ratio of green (live) and red (dead) fluorescence intensities. The shift in the ratio for each strain over the first 6 hours (Figure 3) was evidence of the relative rate of cell death for each microorganism on both dressings. With each microorganism there was a steady decline in living cells over time on the silver‐free alginate samples, probably because of natural cell death and the phototoxic effect of the laser. However, for each species the cell death rate was notably greater over this initial time period on the RESTORE silver alginate fibres, indicating the microbicidal effect of that dressing.

Figure 3.

Relative cell viability on inoculated wound dressing fibres, as showed by the change in ratio of live and dead‐stained cells measured by Confocal laser scanning microscopy imaging and relative green and red fluorescence intensity analysis.

DISCUSSION

Wounds are frequently contaminated by a mixed population of microorganisms that can lead to colonisation or infection, which in turn, has been associated with impaired wound healing. The concept of ‘critical colonisation’ implies that once a particular bioburden associated with infection is reached (>105 CFU/g of wound tissue), impaired wound healing occurs and the use of antimicrobial dressings is advocated 27, 28. However, this premise does not take into consideration the wound type nor the microorganisms involved in wound colonisation, because impairment of healing can occur at lower microbial bioburden when opportunistic pathogenic strains are involved. A more scientifically and clinically accepted term, used instead of critically colonised, is biofilm infected 23, 29. Interestingly, recent studies assessing the bioburden of chronic wounds showed no relationship between bacterial counts and healing rates 7, 10, 30.

While the application of topical antimicrobials can reduce the microbial burden within a wound dressing, the eradication of biofilm microorganisms is generally not reported on. A wide range of antimicrobial dressings are available that promote reduction in planktonic microbial levels and enhance wound repair. In recent years, much focus has been given to the potential role of silver dressings in inhibiting wound microflora 22, 25, 30, 31 and the aim of this study was to investigate the performance of a commercially available silver‐containing alginate dressing against prevalent wound microorganisms.

The findings of the study showed that the RESTORE silver alginate dressing had activity against all of the tested wound isolates including Gram‐positive and Gram‐negative bacteria, as well as fungi. These test isolates had been selected for based on their prevalence within wounds and their pathogenic associations. This broad activity spectrum of ionic silver is widely recognised for silver alginate dressings, in particular against burn wound (32) and chronic wound isolates (33) although, as with several silver containing wound dressings, activity has been reported to be greater against Gram‐negative bacteria compared with Gram‐positive bacteria 22, 34. Indeed, in this present study, a 2 hours exposure of the silver dressing to one of the S. aureus strains did appear to have limited effects in terms of a log10 reduction, although the more extensive overnight exposure used in the CZOI assay proved effective against this strain. The spectrum of activity of RESTORE silver alginate did vary with species and strains, as has been previously reported 32, 33, 35. The absence of silver resistance in this study was, however, reassuring given that there are now several reports of isolates exhibiting tolerance and inherent resistance to ionic silver 36, 37, 38.

Dressings exert their activity, at least in part, by making ionic silver available to the local wound dressing environment. Hence, a loss of antimicrobial efficacy may be anticipated as the silver concentration reduces in the dressing over time, because of the demands of the microbial bioburden. This is important in situations where wound dressings may be in place for several days, with silver alginate dressings recently being shown to demonstrate efficacy for up to 21 days (24). For this reason, to examine the antimicrobial persistence of the test dressing, the CZOI assay was designed to monitor performance over time, up to 13 days, until the antimicrobial effect was no longer apparent. It was therefore significant to see that even when challenged daily, the efficacy of the silver dressing was maintained for several days, particularly against prevalent wound pathogens such as P. aeruginosa, S. pyogenes, C. albicans and strict anaerobic bacteria.

The use of live/dead viability staining with CLSM to observe microbial kill within the dressing environment is a novel approach, although a method had previously been described by Newman et al. in a study examining the antimicrobial properties of a silver salt‐containing Hydrofiber wound dressing (39). However, the method by Newman et al. did not take into account the full extent of inadvertent microbial killing induced by the confocal lasers. The effect of kill by the lasers was fully validated by including the control dressing in this study to evaluate the antimicrobial activity of the silver containing wound dressing. Using relative intensity measurements to calculate the change in total cell viability is not ideal as it does not take into account the potential movement of the microorganisms. This may take cells out of the focus of the field being scanned and change the total number of organisms counted. Nor does it take into account possible bleaching of the fluorescent signal. However, despite these limitations, the technique was able to provide good quantification of relative microbial viability in the image from each time point and, therefore, the rate of cell death in real time. This method proved to be a useful way of visualising the effect of the dressing fibres on the microorganisms and could certainly be used to investigate the antimicrobial efficacy of other such wound care products in the future.

As shown in Figure 3, calculating the relative death rate for the first 6 hours after dressing inoculation showed an overall decline in total viability for both silver and silver‐free dressings. The general trend of decline presumably reflects the ‘natural’ death rate under these conditions. Regardless, the significantly greater losses of viability in the 6 hours after inoculation of the silver alginate fibres compared with the control indicate a rapid microbiocidal effect because of the presence of the ionic silver. The importance of this rapid killing effect within the RESTORE silver alginate wound dressing cannot be understated, because not only will microorganisms be removed from the wound dressing environment but the death of these microorganisms will effectively prevent further proliferation within the dressing and subsequent recontamination of the wound. While further assessment of the performance of this dressing against true biofilms is warranted, these studies highlight the potential value of RESTORE silver alginate in reducing the microbial bioburden within the dressing and thus creating an environment conducive to wound healing.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We wish to acknowledge the support for this research and for Dr S Hooper that was provided by a Knowledge Transfer Partnership (KTP) between Cardiff University and Advanced Medical Solutions.

REFERENCES

- 1. Percival SL, Dowd S. The microbiology of wounds. In: Percival SL, Cutting K, editors. Microbiology of wounds. London: CRC Press, 2010:187–217. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schultz GS, Sibbald RG, Falanga V, Ayello EA, Dowsett C, Harding K, Romanelli M, Stacey MC, Teot L, Vanscheidt W. Wound bed preparation: a systematic approach to wound management. Wound Repair Regen 2003;11:S1–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bjarnsholt T, Kirketerp‐Møller K, Jensen PØ, Madsen KG, Phipps R, Krogfelt K, Høiby N, Givskov M. Why chronic wounds will not heal: a novel hypothesis. Wound Repair Regen 2008;16:2–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fonder MA, Lazarus GS, Cowan DA, Aronson‐Cook B, Kohli AR, Mamelak AJ. Treating the chronic wound: a practical approach to the care of nonhealing wounds and wound care dressings. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008;58:185–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sen CK, Gordillo GM, Roy S, Kirsner R, Lambert L, Hunt TK, Gottrup F, Gurtner GC, Longaker MT. Human skin wounds: a major and snowballing threat to public health and the economy. Wound Repair Regen 2009;17:763–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gist S, Tio‐Matos I, Falzgraf S, Cameron S, Beebe M. Wound care in the geriatric client. Clin Interv Aging 2009;4:269–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Davies CE, Hill KE, Newcombe RG, Stephens P, Wilson MJ, Harding KG, Thomas DW. A prospective study of the microbiology of chronic venous leg ulcer tissue biopsies to reevaluate the clinical predictive value of tissue biopsies and swabs. Wound Repair Regen 2007;5:17–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hart J. Inflammation. 2: its role in the healing of chronic wounds. J Wound Care 2002;11:245–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Robson MC, Mannari RJ, Smith PD, Payne WG. Maintenance of wound bacterial balance. Am J Surg 1999; 178:399–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ratliff CR, Getcbell‐White SI, Rodebeaver GT. Quantitation of bacteria in clean, nonhealing, chronic wounds. Wounds 2008;20:279–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Trengove NJ, Stacey MC, McGechie DF, Mata S. Qualitative bacteriology and leg ulcer healing. J Wound Care 1996;5:277–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Davis SC, Ricotti C, Cazzaniga A, Welsh E, Eaglstein WH, Mertz PM. Microscopic and physiologic evidence for biofilm‐associated wound colonization in vivo. Wound Repair Regen 2008;16:23–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. James GA, Swogger E, Wolcott R, Pulcini E, Secor P, Sestrich J, Costerton JW, Stewart PS. Biofilms in chronic wounds. Wound Repair Regen 2008;16:37–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hill KE, Malic S, McKee R, Rennison T, Harding KG, Williams DW, Thomas DW. An in vitro model of chronic wound biofilms to test wound dressings and assess antimicrobial susceptibilities. J Antimicrob Chemother 2010;65:1195–1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Naves P, Del Prado G, Ponte C, Soriano F. Differences in the in vitro susceptibility of planktonic and biofilm‐associated Escherichia coli strains to antimicrobial agents. J Chemother 2010;22:312–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fumal I, Branham C, Paquet P, Piérard‐Franchimont C, Piérard GE. The beneficial toxicity paradox of antimicrobials in leg ulcer healing impaired by a polymicrobial flora: a proof‐of‐concept study. Dermatol 2002;204:70–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shah M, Mohanraj M. High levels of fusidic acid‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus in dermatology patients. Br J Dermatol 2003;148:1018–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Howell‐Jones RS, Wilson MJ, Hill KE, Howard AJ, Price PE, Thomas DW. A review of the microbiology, antibiotic usage and resistance in chronic skin wounds. J Antimicrob Chemother 2005;55:143–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. O’Meara SM, Cullum NA, Majid M, Sheldon T. Systematic reviews of wound care management: (3) antimicrobial agents for chronic wounds; (4) diabetic foot ulceration. Health Technol Assess 2000;4:1–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wolcott RD, Rumbaugh KP, James G, Schultz G, Phillips P, Yang Q, Watters C, Stewart PS, Dowd SE. Biofilm maturity studies indicate sharp debridement opens a time – dependent therapeutic window. J Wound Care 2010;19:320–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jones V, Grey JE, Harding KG. Wound dressings. BMJ 2006;332:777–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ip M, Lui SL, Poon VK, Lung I, Burd A. Antimicrobial activities of silver dressings: an in vitro comparison. J Med Microbiol 2006;55:59–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Beele H, Meuleneire F, Nahuys M, Percival SL. A prospective randomised open label study to evaluate the potential of a new silver alginate/carboxymethylcellulose antimicrobial wound dressing to promote wound healing. Int Wound J 2010;7:262–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bradford C, Freeman R, Percival SL. In vitro study of sustained antimicrobial activity of a new silver alginate dressing. J Am Coll Certif Wound Spec 2009;1:117–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cavanagh MH, Burrell RE, Nadworny PL. Evaluating antimicrobial efficacy of new commercially available silver dressings. Int Wound J 2010;7:394–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Andrews JM. The development of the BSAC standardized method of disc diffusion testing. J Antimicrob Chemother 2001;48(S1 Suppl):29–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schultz G, Barillo D, Mozingo D, Chin G. Wound bed preparation and a brief history of TIME. Int Wound J 2004;1:19–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sibbald RG, Williamson D, Orsted HL, Campbell K, Keast D, Krasner D, Sibbald D. Preparing the wound bed – debridement, bacterial balance, and moisture balance. Ostomy Wound Manag 2000;46:14–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Percival SL, Thomas J, Williams DW. Biofilms and bacterial imbalances in chronic wounds: anti‐Koch. Int Wound J 2010;7:169–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Miller CN, Carville K, Newall N, Kapp S, Lewin G, Karimi L, Santamaria N. Assessing bacterial burden in wounds: comparing clinical observation and wound swabs. Int Wound J 2011;8:45–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kotz P, Fisher J, McCluskey P, Hartwell SD, Dharma H. Use of a new silver barrier dressing, ALLEVYN Ag in exuding chronic wounds. Int Wound J 2009;6:186–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Thomas JG, Slone W, Linton S, Okel T, Corum L, Percival SL. In vitro antimicrobial efficacy of a silver alginate dressing on burn wounds isolates. J Wound Care 2011;20:124–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Percival SL, Slone W, Linton S, Okel T, Corum L, Thomas JG. The antimicrobial efficacy of a silver alginate dressing against a broad spectrum of clinically relevant wound isolates. Int Wound J 2011;8:237–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kim J, Kwon S, Ostler E. Antimicrobial effect of silver‐impregnated cellulose: potential for antimicrobial therapy. J Biol Eng 2009;3:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Percival SL, Slone W, Linton S, Okel T, Corum L, Thomas JG. Use of flow cytometry to compare the antimicrobial efficacy of silver‐containing wound dressings against planktonic Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Wound Repair Regen 2011;19:436–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Landsdown AB, Williams A. Bacterial resistance to silver in wound care and medical devices. J Wound Care 2007;16:15–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Percival SL, Bowler PG, Russell D. Bacterial resistance to silver in wound care. J Hosp Infect 2005;60:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Woods EJ, Cochrane CA, Percival SL. Prevalence of silver resistance genes in bacteria isolated from human and horse wounds. Vet Microbiol 2009;138:325–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Newman GR, Walker M, Hobot JA, Bowler PG. Visualisation of bacterial sequestration and bactericidal activity within hydrating hydrofiber wound dressings. Biomaterials 2006;27:1129–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]