Abstract

To assess the effect of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) [Chinese herbal medicine ointment (CHMO), acupuncture and moxibustion] on pressure ulcer. In this study, we searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, CENTER, CBM, CNKI, WAN FANG and VIP for articles published from database inception up to 4 April 2011. We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs), which compared the effects of TCM with other interventions. We assessed the methodological quality of these trials using Cochrane risk of bias criteria. Ten of 565 potentially relevant trails that enrolled a total of 893 patients met our inclusion criteria. All the included RCTs only used CHMO intervention, because acupuncture and moxibustion trials failed to meet the inclusive criteria. A meta‐analysis showed beneficial effects of CHMO for pressure ulcer compared with other treatments on the total effective rate [risk ratio (RR): 1·28; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1·20–1·36; P = 0·53; I 2 = 0%), curative ratio (RR: 2·02; 95% CI: 1·73–2·35; P = 0·11; I 2 = 37%) and inefficiency rate (RR: 0·16; 95% CI: 0·02–0·80; P = 0·84; I 2 = 0%). However, the funnel plot indicated that there was publication bias in this study. The evidence that CHMO is effective for pressure ulcer is encouraging, but due to several caveats, not conclusive. Therefore, more rigorous studies seem warranted.

Keywords: Acupuncture, Bedsores, Chinese herbal medicine ointment, Moxibustion, Pressure ulcer

INTRODUCTION

Pressure ulcers, also known as bedsores or pressure sores, are regions of localised damage to the skin and deeper tissue layers affecting muscle, tendon and bone as a result of constant pressure due to impaired mobility 1, 2. The pressure leads to poor circulation and eventually contributes to cell death, skin breakdown and the development of an open wound. If not adequately treated, open ulcers can become a source of pain, disability and infection.

Pressure ulcers are generally graded according to the European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel and National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel as follows (3):

-

1

Grade I: Intact skin with non blanchable erythema. Discolouration of the skin, warmth, oedema, hardness or pain may also be used as indicators. Darkly pigmented skin may not have visible blanching.

-

2

Grade II: Partial thickness skin loss involving epidermis, dermis or both, with a red pink wound bed, without slough. The ulcer may also present as an abrasion or blister.

-

3

Grade III: Full thickness tissue loss, but not exposing muscle, tendon or bone. Some slough may be present. May include undermining and tunnelling.

-

4

Grade IV: Full thickness tissue loss with exposed bone, tendon or muscle. Slough or eschar may be present. Often include undermining and tunnelling.

Pressure ulcer prevalence varies widely depending on patients who have predisposing risk factors, such as poor nutrition, confinement to a bed or wheelchair, and other medical problems (especially spinal cord injury, hip fracture or dementia) 4, 5, 6, 7. Common sites include the sacrum (tailbone), back, buttocks, heels, back of the head and elbows 6, 7.

Pressure ulcer are widespread, expensive and painful health care problems, with prevalence rates ranging from 8·8% to 53·2% 8, 9 and incidence rates vary from 7% to 71·6% 10, 11. A multinational study involving five countries reported that the overall prevalence of pressure ulcers was approximately 18% of hospital patients (12). Pressure ulcer prevalence ranges from 5·1% to 32·1% in the UK, 4·7% to 29·7% in the USA and Canada (13). These ulcers represent a major burden of sickness and reduced quality of life for patients and their carers, and are considerable cost both to the patients (14) and the health service (15). The annual treatment cost of pressure ulcers has been estimated to range from £1·4 to 2·1 billion; this was broadly equal to total UK National Health Service expenditure on mental illness, or the total cost of community health services (16).

Treatment strategies for pressure ulcers often represent a great financial burden in the form of direct costs resulting from loss of work and medical expenses. Effective and adequate treatment is an important issue for patients, clinicians and policy makers.

Pressure ulcer treatment is now a huge industry and involves a range of interventions (3). In addition to traditional interventions for pressure ulcer, such as antimicrobial, mattress (17), dressing (18), hydrotherapy (19), skin substitutes (20), negative pressure therapy (21), electrical stimulation (22), ultrasound (23), electromagnetic therapy (24), laser therapy (25) and light therapy (26), therapies collectively called Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) are commonly used. This includes, for example, CHMO, acupuncture and moxibustion. The effect of these therapies for the treatment of pressure ulcer is not without dispute; therefore, a systematic review was conducted in order to assess the effect of TCM on pressure ulcer in this study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Literature classification

Only RCTs on CHMO, acupuncture and moxibustion were considered. CHMO is an oil‐based ointment containing sesame oil, honey and other small quantities of plant ingredients 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36 (Table 1B). Many studies found that CHMO promotes epithelial repair, inhibits bacterial growth, soothes wounds, retains moisture, relieves pain from wound surface, provides the optimum physiological environment for healing and results in improvement for scar formation 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36. Acupuncture is defined according to traditional acupuncture theory, and needling in acupoints is based on the system of meridians. Moxibustion is an East Asian therapeutic method which generates heat by burning a herbal preparation containing Artemisia vulgaris (mug‐wort), applied close to acupuncture points (37). Moxibustion treatment, though uncommon in Western countries, has been shown to have benefits for pressure ulcer (38), pain (39) and cancer care (40).

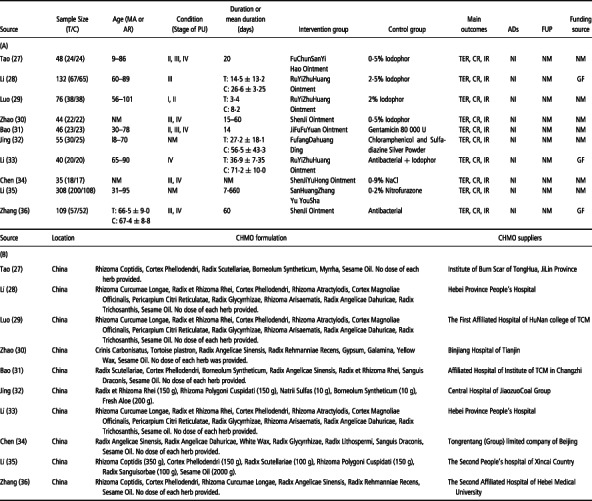

Table 1.

The characteristics of the included RCTs

Data sources

The databases of MEDLINE, EMBASE, CENTER, CBM, CNKI, WAN FANG and VIP were searched from inception through 4 April 2011, to identify relevant RCTs. The following search terms were used: pressure ulcer, pressure sore, bedsore, decubitus ulcer, treatment, TCM, herbal medicine ointment, acupuncture, moxibustion, randomised and clinical trials. We also performed a hand search to identify any other articles. The trails should be selected with no language restrictions.

Study eligibility

Studies fulfilling the following criteria were eligible for inclusion: the study design applied to RCTs; subjects with pressure ulcers belonged to the I–IV phase; more than 30 subjects involved; TCM intervention (CHMO, acupuncture and moxibustion) applied; more than one of the sham groups was placebo; and at least one of the outcomes applied in the study. However, studies with duplication, insufficient information, mixed intervention and crossover design were excluded.

Data extraction and analysis

Two independent reviewers (JHY and LBQ) extracted data according to predefined criteria. If the two reviewers disagreed, the difference was settled through discussion. If a consensus could not be reached, a third reviewer (XR) was consulted.

Quality assessment and data synthesis

The methodological quality of the included RCTs was assessed using the risk of bias. The relative risk with 95% CIs was calculated using Collaboration's software (Review Manager 5·1) for dichotomous data in each outcome measured.

RESULTS

Studies included

The search strategy generated 565 potentially relevant articles. Ten trials, involving a total of 893 participants, were eligible for inclusive and exclusive criteria 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the trial selection process. PU, pressure ulcer.

Study characteristics

The characteristics of the 10 included studies are presented in Table 1A. The sample size was varied from 35 to 308. The age of all the subjects ranged from 9 to 101, except two studies that did not mention age 30, 34. The duration of the treatment fluctuated from 1 week to 3 months in most studies 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 36, except one study ranging from 7 to 660 days (35). The subjects with pressure ulcers were at stages I–IV. The intervention was only CHMO, because acupuncture and moxibustion studies did not meet the inclusive criteria. The main outcomes were the total effective rate, curative ratio and inefficiency rate. None of the RCTs reported any side effects in the treatment group compared with the placebo group, and none of these trails mentioned any follow‐up period. Moreover, three trials were funded by the Government 28, 33, 36, while the other seven studies were not mentioned.

Study quality

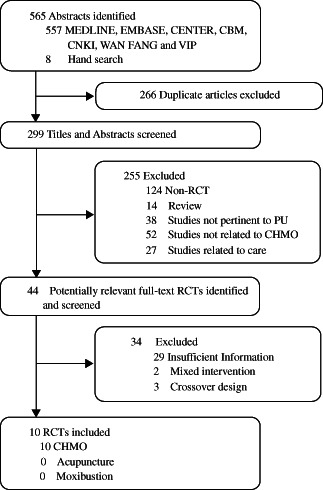

The quality of all 10 studies was assessed with Cochrane risk of bias (Figure 2A, B). Four (40%) of the included RCTs described the sequence generation 29, 30, 36. Three (30%) of them used proper methods 29, 30, 33, 36, while the other one (10%) did not report properly (33). None of the 10 RCTs reported any allocation concealment, expect two (20%) trails which concealed inadequately 32, 33. For incomplete outcome and selective data reporting, 7 (70%) of the 10 trials depicted data appropriately and comprehensively 28, 30, 31, 33, 34, 35, 36, while three (30%) studies failed to provide sufficient data 27, 29, 32. As for performance, attrition and other bias described, all 10 RCTs did not provide any information about those risks.

Figure 2.

(A) Methodological quality graph: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies. (B) Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Outcome measurement

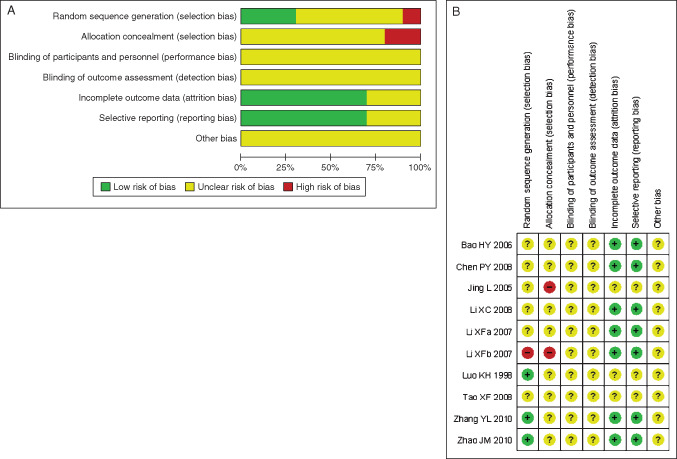

Ten included 10 RCTs assessed the effects of CHMO compared to other interventions on total effective rate, curative ratio and inefficiency rate, respectively 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36 (Figure 3A–C). Nine trials showed a favourable effect of CHMO on total effective rate 27, 28, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, while the other one failed to do so (29) (Figure 3A). Seven studies showed positive effects of CHMO on curative ratio 28, 29, 30, 31, 33, 34, 35, while the others did not 27, 32, 36 (Figure 3B). Six trails showed significant effects of CHMO on inefficiency rate 28, 29, 30, 31, 35, 36, while the other four failed to do so 27, 32, 33, 34 (Figure 3C). A meta‐analysis showed that CHMO had encouraging therapeutic effects compared to other treatments on total effective rate (RR: 1·28; 95% CI: 1·20–1·36; heterogeneity: x 2 = 8·08; P = 0·53; I 2 = 0%) (Figure 3A), curative ratio (RR: 2·02; 95% CI: 1·73–2·35; heterogeneity: x 2 = 14·22; P = 0·11; I 2 = 37%) (Figure 3B) and inefficiency rate (RR: 0·16; 95% CI: 0·02–0·80; heterogeneity: x 2 = 4·98; P = 0·84; I 2 = 0%), respectively (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

(A) Forest plot of comparison: 1 treatment versus control, outcome: 1·1 the total effective rate after treatment. (B) Funnel plot of comparison: 1 treatment versus control, outcome: 1·2 the curative ratio after treatment. (C) Funnel plot of comparison: 1 treatment versus control, outcome: 1·3 the inefficiency ratio after treatment.

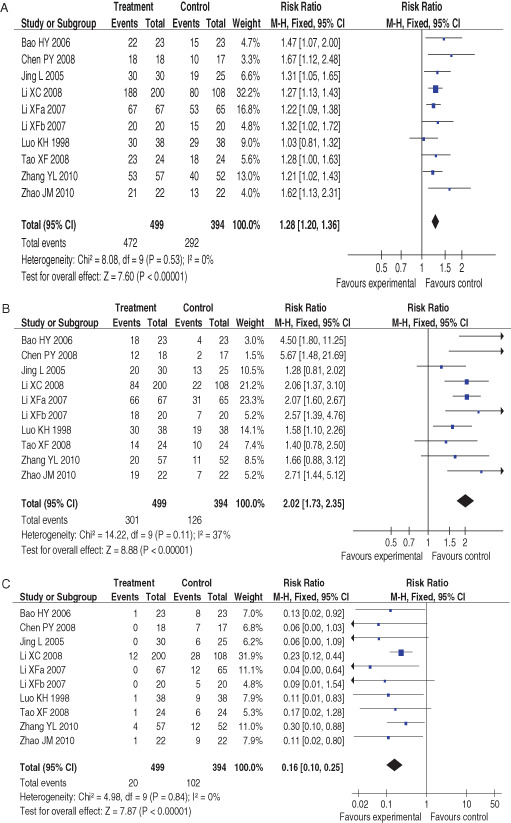

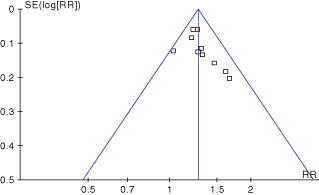

Funnel plots

In our study, the asymmetric funnel plots of the 10 clinical trials showed that there was publication bias (Figure 4). The small total sample size, treatment effect and location might be the reasons of publication bias in this study.

Figure 4.

The funnel plots of 10 included randomised controlled trials.

DISCUSSION

This review involved a systematic assessment of RCTs which related to the effect of TCM by evaluating published literature. The trials assessed the efficacy of several types of CHMO on various medical conditions. However, most trials involved only a small sample and the methodological quality of the trials was low.

The majority of pressure ulcers resulted from other diseases, such as stroke 28, 31, 33, 36, heart disease 28, 31, 33, 36, sequelae of traumatic brain injury 28, 31, 32, 33, 36, paraplegia 31, 32, 36, bone fracture 32, 33, diabetes 31, 36 and renal failure 28, 31. The drugs for these diseases might also have positive effects on pressure ulcer, which may affect the study efficacy of CHMO.

There was not significant difference of gender, age and ulcer grades between intervention group and sham group before treatment in most trials. Of 10 studies, six trails described the comparison of the gender, age and ulcer grades between two groups 27, 28, 29, 33, 34, 36, while the other four did not mention them 30, 31, 32, 35. The lacking comparison data of basic information, mentioned above, limited our ability to meaningfully compare intervention effects between two groups.

The age of all patients ranged from 9 to 101, and the duration of intervention fluctuated from 10 to 660 days (Table 1A). Given such variability in terms of age and length, therapeutic intervention and sham treatments, it is difficult to lead to any definite conclusions. The total sample size and total number of RCTs included in our study, however, were too small to draw firm conclusions about the superiority of CHMO.

All 10 included studies described wound debridement in details 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36 (Table 2). Of 10 studies, three studies failed to provide sufficient information about the usage of CHMO and placebo 27, 30, 32, and all studies did not provide any information about the dosage of CHMO and placebo 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36 (Table 2). All 10 RCTs depicted wounds care in details 27, 28, 29, 30, 32, 33, 34, 36, expect two trails failed to mention it 31, 35 (Table 2). When it comes to the practicers and carers of all patients with pressure ulcers, only two studies reported that nurses were in charge of patients suffered from bedsores 28, 33 (Table 2). The lacking data of management in any of the 10 studies, stops us from drawing firm conclusions about the effect of CHMO.

Table 2.

The intervention details of the included studies

| Clean wounds | Intervention | Care | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | Treatment group | Control group | Treatment group | Control group | Treatment group | Control group | Practicers and carers |

| Tao (27) | Clean the wound with 0·9% normal saline. | Apply FuChunSanYi Hao ointment directly on wounds. | Cover the wounds with sterile gauze soaked with 0·5% Iodophor. | Changing position one time per hour | Not mentioned | ||

| according to the Moving Around Card. | |||||||

| As for pressure ulcers at III, IV stages, | Cover the wounds with sterile gauze once a day, 10 days for a course of treatment. | Keep the beds clean. | |||||

| removal necrosis tissue completely, then | A good diet with rich nutrients. | ||||||

| clean the wound with 0·9% normal saline. | |||||||

| Li (28) | Clean the wound with | Clean the wound with | Apply RuYiZhuHuang ointment with thickness about 1 mm directly on wounds with scope over the wound edges about 0·5 cm, then cover the wounds with sterile gauze every other day | Cover the wounds with sterile gauze soaked with Gentamicin first, then with sterile gauze soaked with 2·5% Iodophor with scope over the wound edges about 0·5 cm once a day. | Removal necrosis tissue. | Nurses | |

| 0·9% normal saline | 2·5% Iodophor | Keeping moving. | |||||

| Keep the beds clean. | |||||||

| A good diet with rich nutrients. | |||||||

| Luo (29) | Clean the wound with 0·9% normal saline, | Apply RuYiZhuHuang ointment with thickness about 2 mm directly on wounds with scope over the wound edges 1–2 cm, then cover the wounds with sterile gauze, once a day. | Cover the wounds with sterile gauze soaked with 2·0% Iodophor with scope over the wound edges 1–2 cm, 3–4 times a day. | Changing position. | Not mentioned | ||

| and the wound edges with 75% | Keep the beds clean. | ||||||

| alcohol disinfection. | A good diet rich in nutrients. | ||||||

| Zhao (30) | Clean the wound with | Apply ShenJi Ointment directly on wounds, then cover the wounds with sterile gauze, once a day. | Cover the wounds with sterile gauze soaked with 0·5% Iodophor. | Use mattresses and cushions. | Not mentioned. | ||

| 0·9% normal saline. | Changing position. | ||||||

| A good diet rich in nutrients. | |||||||

| Bao (31) | Clean the wound with hydrogen peroxide | Apply JiFuFuYuan Ointment directly on wounds, then cover the wounds with sterile gauze, once a day. | Cover the wounds with sterile gauze soaked with 80 000 U Gentamycin, twice a day. | Not mentioned. | Not mentioned | ||

| solution first, then with 0·9% normal saline. | |||||||

| Removal necrosis tissue. | |||||||

| Clean the wound with 0·9% normal saline again. | |||||||

| Clean the tissue around wounds with Iodophor. | |||||||

| Jing (32) | Removal necrosis tissue. | Cover the wounds with sterile gauze soaked with FufangDahuang Ding, then cover the wounds with sterile gauze. | Cover the wounds with Chloramphenicol and Sulfadiazine Silver | Changing position. | Not mentioned | ||

| Powder. | |||||||

| Clean the wound with 0·9% normal saline. | A good diet rich in nutrients. | ||||||

| Li (33) | Clean the wound with | Apply RuYiZhuHuang Ointment with thickness about 1 mm directly on wounds, then cover the wounds with sterile gauze, every other day. | Apply antibacterial directly on wounds, then cover the wounds with sterile gauze, every other day. | Changing position. | Nurses | ||

| 0·9% normal saline, and the wound | Keep the skin clean. | ||||||

| edges with Iodophor disinfection. | A good diet rich in nutrients. | ||||||

| Chen (34) | III: Clean the wounds with 0·02% | Apply ShenJiYuHong ointment directly on wounds, then cover the wounds with sterile gauze once a day, 4 weeks for a course of treatment. | Cover the wounds with the Vaseline of sterile gauze, then with sterile gauze once a day, 4 weeks for a course of treatment. | Changing position. | Not mentioned. | ||

| nitrofurazone, then with 0·5% metronidazole. | A good diet rich in nutrients. | ||||||

| IV: Clean the wounds with 3% hydrogen | |||||||

| peroxide and 1:5000 potassium permanganate. | |||||||

| Removal necrosis tissue. | |||||||

| Cover the wounds with sterile gauze | |||||||

| soaked with 0·9% normal saline. | |||||||

| Li (35) | Clean the wounds with 3% hydrogen | Apply SanHuangZhangYu YouSha directly on wounds, then cover the wounds with sterile gauze, once a day. | Cover the wounds with sterile gauze soaked with 0·2% nitrofurazone, then cover the wounds with sterile gauze, once a day. | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | ||

| peroxide solution first, then with 0·9% | |||||||

| normal saline. | |||||||

| Removal necrosis tissue. | |||||||

| Clean the wounds with 1/1000 | |||||||

| Bromogeramine disinfection. | |||||||

| Zhang (36) | Clean the wounds by infusing and washing | Apply ShenJi Ointment directly on wounds, then cover the wounds with sterile gauze, once a day with more secretions and 2–3 days one time; 30 days for a course of treatment. | Cover the wounds with Ethacridine gauze, once a day with more secretions and 2–3 days one time; 30 days for a course of treatment. | Changing position. | Not mentioned | ||

| wounds with high sensitive antibiotic from | Use mattresses and cushions. | ||||||

| bacterial culture and drug susceptibility test. | Keep the skin clean. | ||||||

| Removal necrosis tissue. | |||||||

CHMO 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34 was used in the intervention groups, while a wide variety of placebo treatments was used in the sham groups (Table 1A). Treatment groups received CHMO 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, whereas the control groups received iodophor 27, 28, 29, 30, antibacterial 31, 32, 35, 36, iodophor and antibacterial (33), and 0·9% NaCl (34) (Table 1A). All 10 trails provided the CHMO formulation, although only 2 of them mentioned the dose of each herb 32, 35 (Table 1B). Most CHMO suppliers were the local hospitals, which might result in different effect with same CHMO treatment. To draw any conclusion of CHMO on bedsores, RCTs should pay attention to control CHMO and placebo effects. Unfortunately, none of the 10 trials made serious attempts to do this and therefore no firm conclusions can be drawn from such studies. Moreover, other important outcomes, such as wound area and symptoms should also be used to assess the effects of CHMO; however, only one of these trials described the wound area comprehensively (36).

In this review, there was a significant difference between CHMO and placebo intervention in terms of total effective rate, curative ratio and inefficiency rate; however, high risk of bias in the included trials prevents us from making firm conclusions (Figure 2A, B). Not a single trial adequately concealed group allocation and 7 of 10 studies did not clearly describe how randomisation was conducted. Moreover, none of the 10 trials reported any blind or blinding procedures. Neither short‐term nor long‐term follow‐ups were described in 10 RCTs, so we are not sure about the effectiveness of CHMO after intervention. Thus, poor reporting and high risks of bias both rendered these studies less reliable.

Few rigorous RCTs testing the effects of CHMO for pressure ulcer are currently available, and the existing studies do not provide much information regarding the superiority of CHMO over other interventions for patients with pressure ulcer. Our meta‐analysis of 10 trials demonstrated that CHMO may be superior to other treatments in pressure ulcer 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36.

The asymmetric funnel plots may have been caused by the poor quality of the trials and publication bias. All 10 trials were conducted in China and published in Chinese language (Table 1B), where most of the papers we found reported positive results, with only a few presenting negative results (41).

Adverse events were not reported in all 10 trials (Table 1A), so we are not sure about the safety of CHMO interventions on pressure ulcers.

Our review has several limitations. First, the incomplete information may have limited the quality and validity of the results. Second, publication bias may also affect the results of this study. Third, the sample size and the total included RCTs number are too small to make definitive judgements, and also there might be the possibility of missing studies. Finally, all the trials were carried out in China, where they have appeared to produce almost no negative studies, which might also be the possible source of bias.

CONCLUSION

The results of our study suggest that CHMO intervention on pressure ulcer is pretty satisfied. However, the paucity of RCTs included in this study, coupled with small sample size and high risk of bias, prevents us from drawing firm conclusions about the effect of CHMO. Overall, the lack of studies with a low risk of bias precludes any strong recommendations, particularly with regard to CHMO. More rigorous high quality RCTs with a low risk of bias and adequate sample sizes are direly needed in the future.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors did not report any conflict of interest regarding this work. This study was funded by Educational Commission of Heilongjiang Province of China No.12511508.

References

- 1. Whitney J, Phillips L, Aslam R, Barbul A, Gottrup F, Gould L, Robson MC, Rodeheaver G, Thomas D, Stotts N. Guidelines for the treatment of pressure ulcers. Wound Repair Regen 2006;14: 663–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Reddy M, Gill SS, Kalkar SR, Wu W, Anderson PJ, Rochon PA. Treatment of pressure ulcers: a systematic review. JAMA 2008;300:2647–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel and National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel. Treatment of pressure ulcers: quick reference guide. Washington DC: National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Reddy M, Gill SS, Rochon PA. Prevention of pressure ulcers: a systematic review. JAMA 2006;296:974–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Woodbury MG, Houghton PE. Prevalence of pressure ulcers in Canadian healthcare settings. Ostomy Wound Manage 2004;50:22–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Torpy JM, Lynm C, Glass RM. Pressure ulcers. JAMA 2003;289:254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zeller JL, Lynm C, Glass RM. Pressure ulcers. JAMA 2006;296:1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Davis CM, Caseby NG. Prevalence and incidence studies of pressure ulcers in two long‐term care facilities in Canada. Ostomy/Wound Manage 2001;47:28–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tannen A, Bours G, Halfens R, Dassen T. A comparison of pressure ulcer prevalence rates in nursing homes in the Netherlands and Germany, adjusted for population characteristics. Research in Nursing and Health 2006;29:588–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Scott JR, Gibran NS, Engrav LH, Mack CD, Rivara FP. Incidence and characteristics of hospitalized patients with pressure ulcers: State of Washington, 1987 to 2000. Plastic Reconstr Surg 2006;117:630–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Whittington KT, Briones R. National prevalence and incidence study: 6‐year sequential acute care data. Adv Skin Wound Care 2004;17:490–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. EPUAP European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel. Summary report on the prevalence of pressure ulcers. EPUAP Review 2002;4:49–57. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kaltenthaler E, Whitfield MD, Walters SJ, Akehurst RL, Paisley S. UK, USA and Canada: how do their pressure ulcer prevalence and incidence data compare? J Wound Care 2010;10:530–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Clark M. The financial cost of pressure ulcer in the UK National Health Services. In: Cherry CW, Leaper DJ, Lawrence CJ, Milward P, editors. Proceedings of 4th European Conference on Advances in Wound Management. London: Macmillan, 1994:48–51. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Touche Ross and Company. The costs of pressure sores. Report to the Department of Health, UK. 1993.

- 16. Bennett G, Dealey C, Posnett J. The cost of pressure ulcers in the UK. Age Ageing 2004;33:230–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Heyneman A, Vanderwee K, Grypdonck M, Defloor T. Effectiveness of two cushions in the prevention of heel pressure ulcers. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs 2009;6:114–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lerman B, Oldenbrook L, Eichstadt SL, Ryu J, Fong KD, Schubart PJ. Evaluation of chronic wound treatment with the SNaP wound care system versus modern dressing protocols. Plast Reconstr Surg 2010;126:1253–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dissemond J. Physical treatment modalities for chronic leg ulcers. Hautarzt 2010;61:387–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mizuno H, Miyamoto M, Shimamoto M, Koike S, Hyakusoku H, Kuroyanagi Y. Therapeutic angiogenesis by autologous bone marrow cell implantation together with allogeneic cultured dermal substitute for intractable ulcers in critical limb ischaemia. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2010;63:1875–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chantelau E. Negative pressure therapy in diabetic foot wounds. Lancet 2006;367:726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Curtis CA, Chong SL, Kornelsen I, Uwiera RR, Seres P, Mushahwar VK. The effects of intermittent electrical stimulation on the prevention of deep tissue injury: varying loads and stimulation paradigms. Artif Organs 2011;35:226–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Moghimi S, Miran Baygi MH, Torkaman G, Mahloojifar A. Quantitative assessment of pressure sore generation and healing through numerical analysis of high‐frequency ultrasound images. J Rehabil Res Dev 2010;47:99–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Aziz Z, Flemming K, Cullum NA, Olyaee Manesh A. Electromagnetic therapy for treating pressure ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;10:CD002930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lanzafame RJ, Stadler I, Coleman J, Haerum B, Oskoui P, Whittaker M, Zhang RY. Temperature‐controlled 830‐nm low‐level laser therapy of experimental pressure ulcers. Photomed Laser Surg 2004;22:483–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Durović A, Marić D, Brdareski Z, Jevtić M, Durd̄ević S. The effects of polarized light therapy in pressure ulcer healing. Vojnosanit Pregl 2008; 65:906–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tao XF, Ren YQ. The effect of FuChunSan YiHao Ointment on the pressure ulcers. Guid J Trad Chinese Med Pharm 2008;5:88. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Li XF, Gong SZ, Lu JE, Zhang WH, Xu HY. The clinical study of RuYi ZhuHuang Ointment on patients with III stage of pressure sores. J Nurs Training 2007;22:1646–7. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Luo KH, Huang SL, Li JH. The clinical observation of RuYi JinHuang Ointment on patients with I and? stage of pressure ulcers. J Hunan College TCM 1998;18:45–6. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhao JM. The clinical observation of ShenJi Ointment on patients with III and IV stage of pressure ulcers. Med Res Edu 2010;27:65–6. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bao HY. The effect of JiFu FuYuan Ointment on patients with bedsores. J Changzhi Med College 2006;20:308–9. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jing L. The effect of Fufang Dahuang Ding on patients with bedsores. J Extern Therap Trad Chinese Med 2005;14:18–9. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Li XF, Gong SZ, Lu JE, Zhang WH, Xu HP. Comparisons of effects of RuYiZhuHuang Ointment and conventional treatment on pressed wound. Liaoning. J Trad Chinese Med 2007;34:1286–7. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chen PY, Sui DS. The effect of ShenJiYuHong Ointment on 18 patients with Pressure ulcers. J New Chinese Med 2008;40:45–7. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Li XC, Wang JF. The clinical observation of SanHuangZhangYuYouSha on patients with bedsores. China Med Herald 2008;5:159. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhang YL, Wang XY, Wang ZH, Duan XD. Study of the basic fibroblast growth factor in decubitus tissue treating with Qufu Shengji ointment. Clin Med China 2010;26:388–91. [Google Scholar]

- 37. World Health Organization Western Pacific Region : WHO International Standard Terminologies on Traditional Medicine in the Western Pacific Region. URL http://www.wpro.who.int/publications/PUB_9789290612487.htm. [accessed on 20 December 2011]

- 38. Dai W, Zhang L. The clinical effect of moxibustion on pressure sore. J Modern Clin Med 2006;32:128. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lee MS, Choi TY, Kang JW, Lee BJ, Ernst E. Moxibustion for treating pain: a systematic review. Am J Chin Med 2010;38:829–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lee MS, Choi TY, Park JE, Lee SS, Ernst E. Moxibustion for cancer care: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. BMC Cancer 2010;10:130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Vickers A, Goyal N, Harland R, Rees R. Do certain countries produce only positive results‐a systematic review of controlled trials. Control Clin Trials 1998;19:159–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]