Abstract

Background

COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, has become a global pandemic, affecting most countries worldwide. Digital health information technologies can be applied in three aspects, namely digital patients, digital devices, and digital clinics, and could be useful in fighting the COVID-19 pandemic.

Objective

Recent reviews have examined the role of digital health in controlling COVID-19 to identify the potential of digital health interventions to fight the disease. However, this study aims to review and analyze the digital technology that is being applied to control the COVID-19 pandemic in the 10 countries with the highest prevalence of the disease.

Methods

For this review, the Google Scholar, PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus databases were searched in August 2020 to retrieve publications from December 2019 to March 15, 2020. Furthermore, the Google search engine was used to identify additional applications of digital health for COVID-19 pandemic control.

Results

We included 32 papers in this review that reported 37 digital health applications for COVID-19 control. The most common digital health projects to address COVID-19 were telemedicine visits (11/37, 30%). Digital learning packages for informing people about the disease, geographic information systems and quick response code applications for real-time case tracking, and cloud- or mobile-based systems for self-care and patient tracking were in the second rank of digital tool applications (all 7/37, 19%). The projects were deployed in various European countries and in the United States, Australia, and China.

Conclusions

Considering the potential of available information technologies worldwide in the 21st century, particularly in developed countries, it appears that more digital health products with a higher level of intelligence capability remain to be applied for the management of pandemics and health-related crises.

Keywords: COVID-19, digital health, information technology, telemedicine, electronic health

Introduction

The novel disease COVID-19, caused by the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, was originally recognized in December 2019 as a case of pneumonia in Wuhan, China; it has since become a global pandemic, affecting most countries worldwide [1]. On March 11, the World Health Organization announced the outbreak of a pandemic and asked for coordinated mechanisms to support readiness and rapid response to the infection across the world's health sectors [2]. As the incidence of COVID-19 continues to rise, health care systems are rapidly facing growing clinical demands [3]. Operational management of a pandemic in the era of modern medicine requires novel technologies, such as digital health, that can support the management of COVID-19 cases in different stages [4]. Digital health as an application of information technology has already been used to improve health care organizations; for example, the National Health Service (NHS) in the United Kingdom has established the NHS Digital information center [5]. Digital health is defined as information technologies that can be applied in three aspects: digital patients, digital devices, and digital clinics. A digital patient is a patient who uses and engages with mobile health (mHealth) devices to change and sustain their behavior, including technologies such as telemedicine, patient self-measurements, and digital retention. Digital devices help solve clinical problems and include smartphone-connected rhythm monitoring devices, wireless and wearable devices, and implantable and ingestible sensors. The digital clinic aspect focuses on generating mHealth data, analyzing it so that it is clinically meaningful, and integrating it within clinical workflows. Aspects of digital clinics include precision-based mHealth and n-of-1 designs, population-based mHealth interventions in resource-limited areas, and mHealth regulation and integration [6].

During the COVID-19 pandemic, digital health–based tools may support organizations and societies more efficiently. They are useful for instant, widespread distribution of information, real-time transmission tracking, virtual venue creation for meetings and official day-to-day operations, and telemedicine visits for patients [7-12]. Such applications during the COVID-19 pandemic have been reported in several publications [13-15]. During the recent months of the COVID-19 outbreak, as countries and their responsible organizations such as health ministries and other officials have focused on controlling the pandemic, many supportive and reliable informatics infrastructures have been developed [12]. These infrastructures were applied in practice to prepare to manage an exponential increase in patients with COVID-19. Various digital health strategies have been used for disease control in different countries. A study conducted by Calton et al [16] provided some tips for applying telemedicine as a means to reduce the transmission of COVID-19. A study conducted by Moazzami et al [17] focused on employing telemedicine to prevent disease among health care providers. A study conducted by Keesara et al [18] referred to the capabilities and potential of digital health to fight COVID-19. However, they reviewed digital health–related solutions in general to address how this technology can support health care systems through introducing various strategic roles, such as surveillance, screening, triage, diagnosis, and monitoring, and contact tracing; no data regarding the use of this approach in practice for fighting COVID-19 were provided [19]. Fagherazzi et al [20] emphasized that the great potential of digital technology for COVID-19 control should be considered at the top level of health systems; they also discussed the challenges that policy makers may face in controlling the crisis using digital solutions. Furthermore, in a macro vision, they revealed the required societal and environmental restructuring required for successfully applying digital health technology to control COVID-19, including the health care system, government, public, industry, environment, and energy [15]. These reviews depict a general image regarding the requirement of digital system use and their applications worldwide [21], with no focus on any specific application in a specific country or region. Although these studies have shed light on the topic of applying digital health solutions for COVID-19 control, there is a gap of deep understanding regarding the application of these technologies in countries where COVID-19 is highly prevalent.

Therefore, this study aimed to review and analyze applied information technology and digital health–related strategies to control the COVID-19 pandemic in the 10 countries with the highest prevalence of the disease.

Methods

In this review study, the databases of Google Scholar, PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus were searched in August 2020 to retrieve publications from December 2019 to August 15, 2020. The combination of keywords for searching is shown below:

(“Corona virus” OR “COVID 19” OR “coronavirus”) AND (computer OR internet OR web* OR mobile OR smart OR email OR video confer* OR telecommunication OR ICT OR “information technology” OR ehealth OR telehealth OR mHealth OR telecare OR telehealth OR telemedicine OR telemonitoring OR digital OR wearable OR IoT OR cloud) AND (Italy OR Spain OR USA OR France OR UK OR Iran OR China OR Netherlands OR Germany OR Belgium)

The inclusion criteria were publications that introduce digital health applications to manage and control COVID-19 in humans, and the exclusion criteria were non-English publications, publications with no abstract, research on data analysis and modeling for prediction of epidemiological parameters, letters to the editor, and review studies. Data were analyzed using descriptive methods. Qualitative analysis of the included studies was performed based on predefined categories. A summary of the reviewed articles is provided in Table 1. Several items were analyzed in each paper, including (1) publication month; (2) country (Italy, Spain, United States, France, United Kingdom, Iran, China, the Netherlands, Germany, and Belgium, as they were the countries where COVID-19 was most prevalent according to the Worldometer website [22]); (3) purpose of the study, including screening, prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of cases (defined as follows: screening: no symptom + no contact with COVID-19 patients; prevention: no symptom + contact with COVID-19 patients with no symptoms; diagnosis: having disease symptoms; treatment of COVID-19 cases: decreasing symptoms dramatically; and follow-up: discharged cases with the fewest symptoms); (4) scope and territory (village, city, region/province, state, country, and international), (5) digital tools, including robots, the Internet of Things, videoconferencing, web-based systems, cloud-based systems, wearable devices, clinical decision support systems (CDSSs), intelligent systems, smartphones, mobile apps, telecommunication systems, websites, digital media, and digital quick response (QR) codes.

Table 1.

Details of the reviewed papers that discussed the application of digital health tools to control the COVID-19 pandemic.

| Author | Journal | Publication month (2020) | Country | Purpose | Scope and territory | Applied digital tools | Application of digital tools |

| Kamel and Geraghty [23] | International Journal of Health Geographics | March | China | Prevention | International | Web-based systems, mobile apps, GISa | Widespread distribution of information and real-time tracking of transmission |

| Yang et al [24] | Clinical Oral Investigations | May | China | Treatment and follow-up | Country | Web-based systems, mobile apps | Telemedicine visits for patients |

| Meng et al [25] | International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy | April | China | Treatment | Region | Cloud-based systems, smartphones, telecommunication systems | Provision of pharmaceutical care activities to patients and physicians by pharmacists |

| Ohannessian et al [26] | JMIR Public Health and Surveillance | February | France | Prevention | Country | Videoconferencing | Offering telemedicine visits for patients |

| Pan et al [27] | Microbes and Infection | February | China | Prevention | Country | Mobile apps | Widespread distribution of information and real-time tracking of transmission |

| Pan et al [28] | Irish Journal of Medical Science | March | China | Screening and prevention | City and country | Mobile apps | Real-time tracking of transmission |

| Sun et al [29] | Annals of Intensive Care | March | China | Treatment | State | Intelligent systems | Early warning systems and screening procedures for patients |

| Hernández-Garcia and Gimenez-Júlvez [30] | JMIR Public Health and Surveillance | April | Collaboration of the United States, Spain, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, Sweden, and Canada | Screening and prevention | International | Websites and digital media | Widespread distribution of information |

| Hua and Shaw [31] | International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health | March | China | Screening, prevention, and follow-up | Region/ province |

Web-based systems, smartphones, websites, digital media, digital QRb codes | Widespread distribution of information, real-time tracking of transmission, provision of information about “fake news” and rumors |

| Drew et al [32] | Science | May | United Kingdom, United States | Screening | International | Mobile app | Widespread distribution of information, real-time tracking of transmission |

| Franco et al [33] | Global Spine Journal | June | United States | Treatment | State | Videoconferencing, telephone | Offering telemedicine visits for patients |

| Gilbert et al [34] | BMJ Open Quality | May | United Kingdom | Prevention | City | Videoconferencing, telephone | Offering telemedicine visits for patients |

| Giudice et al [35] | International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health | May | Italy | Follow-up | Region | Videoconferencing | Offering telemedicine visits for patients |

| Gong et al [36] | Journal of Medical Internet Research | April | China | Prevention | Country | Telecommunication system | Offering telemedicine visits for patients |

| Gong et al [37] | Journal of Medical Internet Research | April | China | Screening | City | Cloud-based system, mobile app, CDSSc | Screening of cases and detection of patients |

| Goodman-Casanov et al [38] | Journal of Medical Internet Research | April | Spain | Prevention |

Country | Telecommunication system | Widespread distribution of information, support for home care and patient self-care |

| Grange et al [39] | Applied Clinical Informatics | April | United States | Prevention, diagnosis, treatment, screening | State | Videoconferencing, CDSS, telecommunication | Offering telemedicine visits for patients |

| Grenda et al [40] | Annals of Surgery | August | United States | Diagnosis, treatment | City | Telecommunication, videoconferencing | Offering telemedicine visits for patients |

| Grossman et al [41] | Neurology | June | United States | Diagnosis, treatment | City | Smartphone, mobile apps | Offering telemedicine visits for patients |

| Hames et al [42] | Journal of Psychotherapy Integration | April | United States, Canada | Prevention |

Country | Telecommunication system | Training |

| Hanna et al [43] | Modern Pathology | June | United States | Prevention, diagnosis | City | Telecommunication system | Diagnosis |

| Hom et al [44] | Journal of Psychotherapy Integration | April | United States | Prevention, treatment | City | Videoconferencing | Telemedicine visits for patients, training |

| Itamura et al [45] | OTO Open | April | United States | Prevention | Country | Videoconferencing | Telemedicine visits for patients |

| Judson et al [46] | Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association | June | United States | Prevention | State | Website | Screening of cases and detection of patients |

| Wu et al [47] | European Respiratory Journal | June | China, Italy, Belgium | Diagnosis | International | CDSS | Classification of patients in triage to find the best route |

| Wang et al [48] | JMIR mHealth and uHealth | June | China | Prevention | Country | Mobile app (WeChat) | Early tracing and quarantine of potential sources of infection |

| Timmers et al [49] | JMIR mHealth and uHealth | June | The Netherlands | Prevention | Country | Mobile app | Education, self-assessment, and symptom monitoring |

| Pepin et al [50] | Journal of Medical Internet Research | June | France | Prevention | International | Wearable devices and activity trackers | Definition of the level of quarantine |

| Rabuna et al [51] | Telemedicine and e-Health | June | Spain | Prevention | Rural area | TELEA digital web platform | Real-time tracking and monitoring of patients; follow-up of patients by telephone, videoconferencing, and email |

| Cheng et al [52] | Community Mental Health Journal | July | United States, Canada, Australia | Prevention | International | Mobile app | Peer-to-peer psychological support for Wuhan health care professionals at the front line of the crisis |

| Castaldi et al [53] | Acta Biomedica | July | Italy | Prevention | Region | Social media | Assessment of the dynamic burden of social anxiety through analysis of data from Facebook and Twitter |

| Blake et al [54] | International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health | July | United Kingdom | Prevention | Country | Digital learning package using agile methodology | Provision of psychologically safe spaces for staff through providing a three-step e-package with evidence-based guidance |

aGIS: geographic information system.

bQR: quick response.

cCDSS: clinical decision support system.

Results

The search of scientific databases and manual searches retrieved 771 relevant articles. The titles and abstracts of all the retrieved publications were evaluated by two authors. Disagreements between the two evaluators were discussed and resolved by consensus. After removal of duplicates, 292 articles remained at this stage. Next, 260 publications were removed because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Afterward, four authors independently reviewed the full text of the remaining publications (N=32). The reviewed papers were studied based on the variables shown in Table 1 and the different distributions discussed below.

For the purpose of this review, studies published from December 2019 to August 15, 2020, were reviewed. The survey identified 32 papers that demonstrated digital health applications to fight the COVID-19 pandemic. The distribution by publication month revealed that the publication of studies regarding digital health and COVID-19 began in February 2020, and the distribution of the 32 publications by month is February, 2 (6%); March, 5 (16%); April, 9 (28%); May, 3 (9%); June, 9 (28%); July, 3 (9%); and the first half of August, 1 (3%).

The projects of digital health application for COVID-19 control were deployed at different geographical levels, from international to rural. Six countries carried out six international projects, and the most common collaborations were among European countries, the United States, China, and Australia. The digital health projects at the international level mainly aimed to track real-time transmission and infected cases, define the level of quarantine, and enable peer-to-peer consultation to support care providers in other countries phytologically and scientifically. The studies of digital health projects for a given purpose in the 32 studies were most frequently conducted at the country level (n=10, 31%), and the other geographical levels were state (n=4, 13%), region (n=3, 9%), city (n=8, 25%), and rural (n=1, 3%). The United States was the country with the highest number of studies of digital health projects to fight COVID-19 (12/32, 38%), and these 12 studies varied the most in geographical scale, including international (n=3, 25%), state (n=3, 25%), country (n=2, 17%), and city (n=4, 13%) levels. The other studied countries ranked by the number of conducted studies were China (11/32, 34%); the United Kingdom (4/32, 13%); Canada, Spain, and Italy (3/32, 9%); Belgium and France (2/32, 6%); and the Netherlands (1/32, 3%).

To show the applied approaches of digital health for certain methods of COVID-19 control, the results were analyzed, and all the papers were categorized into six domains. These categories, their frequencies and percentages, and their applications for COVID-19 control are presented in Table 2. Some articles mentioned more than one approach to using digital health to control the COVID-19 pandemic.

Table 2.

The frequency of digital health methods and their applications for COVID-19 pandemic control.

| Domain number | Applied digital health solutions | COVID-19 control approaches | Digital health application projects (N=37), n (%) |

| 1 | Digital learning package, mobile apps, and web-based systems | Widespread distribution of information | 7 (19) |

| 2 | GISsa, QRb codes, and wearable devices | Real-time tracking of transmission, activity tracking, and quarantine-level analysis | 7 (19) |

| 3 | Web-based systems and mobile apps, videoconferencing, and telephone | Telemedicine visit services and virtual venues for meetings | 11 (30) |

| 4 | Cloud- and mobile-based systems | Self-care and patient monitoring, training, and diagnosis | 7 (19) |

| 5 | Intelligent systems and CDSSsc | Early warning and detection, screening, and triage | 4 (10) |

| 6 | Social media | Dynamic burden of the pandemic and analysis of its consequences | 1 (3) |

aGISs: geographic information systems.

bQR: quick response.

cCDSSs: clinical decision support systems.

According to the results, telemedicine visit services (11/37, 30%), especially in the United States (6/11, 54%), were the most commonly applied pandemic control approach. Using electronic methods to inform people about the disease, methods to prevent disease spread, and protection methods was the second-ranked approach, in addition to two other solutions of geographic information systems (GISs), QR codes, and wearable devices for real-time transmission tracking as well as cloud-based and mobile app usage for patient monitoring and self-care at home (all 7/37, 19%). A few studies were identified regarding the application of intelligent systems and CDSSs (4/37, 10%) and social media data analysis (1/37, 3%) for screening and burden of disease analysis purposes.

Discussion

Principal Findings

The COVID-19 pandemic has spread worldwide, costing lives and bringing upheaval and change to societies and economies. Although the global scientific community is racing to discover effective vaccines and therapeutics, the most essential defense remains public health measures such as personal hygiene and mass physical distancing. To successfully implement these two main measures, digital health and information technologies have emerged to support health systems, and they offer opportunities to reshape current health care systems. The aim of this study was to review the most significant digital health tools applied to fight COVID-19 in the 10 countries that have been most affected by the disease. These tools help governments and people to engage in strategies to control the COVID-19 pandemic through addressing the most urgent needs, including immediate outbreak response and impact mitigation. In China, which is the first country affected by the virus [55] and the most populous country globally, many researchers have worked on multiple aspects of SARS-CoV-2; it is the second most frequent origin country of the included studies. The burden of SARS-CoV-2 could be massive in populous countries; thus, these studies are worthy of investment in these countries. Studies that reported the development of models to predict epidemiological indicators were ignored, as they have not yet yielded any digital tools and require further development [56-59].

Distributing widespread information and tracking real-time transmission were the two most frequent goals of the studies. The former may originate from the importance of prevention in pandemic diseases as well as the simplest task of using information systems. The latter may be a focus in the literature because of the knowledge obtained from the previous experience of epidemics such as influenza and Zika virus [60-62]. Additionally, telemedicine visits for patients may be beneficial for populations because screening and follow-up of patients can be performed while maintaining social distancing in the population [63]. It appears that investigating the infrastructures needed for this technology could have great potential to mitigate these types of crises. In addition to the whole populations that can benefit from digital health technologies, more attention should be paid to interventions for travelers, as they can spread SARS-CoV-2 to other locations and even globally [64].

It has been shown that cell phones can be beneficial for health care [65]; due to their high influence among global populations, these tools are well suited for widespread distribution of information to these populations. Mobile apps are also used for tracking real-time transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Other potentially useful digital health tools are web-based apps and websites; these tools can also distribute information and track transmission. Videoconferencing and telecommunication also appear to be useful barriers to the spread of COVID-19 by enabling social distancing. Moreover, other industries may use teleservices to prevent the dissemination of disease.

Due to time limitations and the different times of onset of the epidemic in different countries, several digital health tools are not included in this paper. These tools have been reported in the news and other resources, and it may be valuable to discuss them as learned lessons for other countries fighting COVID-19. Therefore, we will review the digital health interventions in the different countries based on their available facilities and other requirements.

China

In China, multiple approaches are being used to manage the COVID-19 pandemic, ranging from web-based and mobile-based systems to cloud-based systems, CDSSs, and intelligent systems. The total number of cases of COVID-19 in this country showed a slight increase after March 1, 2020, based on the data in [66]. However, this decrease in COVID-19 cases was affected by multiple factors, and the effect of eHealth tools on the decrease should be evaluated. China has widely applied an eHealth app named Health Code to indicate a person’s health status in the past day [67].

China has established a plan to spend approximately US $1.4 trillion on digital infrastructure. This infrastructure upgrade program includes developing 5G networks, industrial internet, data centers, and artificial intelligence [68], which could improve the country’s capability to fight pandemics.

Italy and Spain

In contrast to Spain, Italy ranks among the four least advanced European countries in the Digital Economy and Society Index published by the European Commission [69], and approximately half the population of Italy has insufficient digital literacy [70]. The adoption of technology to prevent and manage the COVID-19 pandemic is unremarkable in these two countries. However, a coronavirus-tracking app was developed in Spain [71]. The statistics of total COVID-19 cases showed a dramatic increase after March 1, 2020, in both countries [66]. It appears that these countries should invest more in technologies to manage the pandemic.

United States

The US government launched a portal [72] for the public that contains information on how to prevent and manage COVID-19. Moreover, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website [73] contains more detailed medical information on the spreading mechanism, symptoms, prevention, and treatment of COVID-19.

France and Belgium

The French app StopCovid was developed to trace infected people to control the spread of SARS-CoV-2. Privacy concerns arose regarding adoption of the app. Belgium has announced that a similar app adoption was canceled due to these issues [74].

United Kingdom

The NHS in the United Kingdom works on nine main areas to digitally respond to the pandemic: provide digital channels for citizen guidance and triage; enable remote and collaborative care with systems and data; deliver digital services for NHS Test and Trace; identify and protect vulnerable citizens; support planning with data, analysis, and dashboards; get data and insights to research communities; support clinical trials; provide secure infrastructure and support additional capacity; and plan for recovery, restarting services, and new needs. The government has categorized initiatives in these areas [75].

Iran

Although our study did not include any papers from this country, the Iranian Ministry of Health developed a national screening program website [76] to identify COVID-19 cases in the early stages.

The Netherlands

The Netherlands is one of the leading countries in Europe in digital health care and data. Approximately 90% of the population has digital records, and the Dutch government has invested over 400 million euros (US $482,980,000) in digital health. Hospitals in the Netherlands have signed up for a COVID-19 web-based portal for sharing patient information. Video consultation was provided by more than 8000 health care providers [77].

Germany

The Health Innovation Hub, established by Germany’s Ministry of Health, has published a list of trusted telemedicine applications. The services provided by these apps include remote consultation, risk assessment, and telemedicine services. Before 2018, the country did not allow remote consultations.

The German parliament passed the Digital Care Act, which acknowledged that digital health is crucial for fighting the COVID-19 pandemic [78].

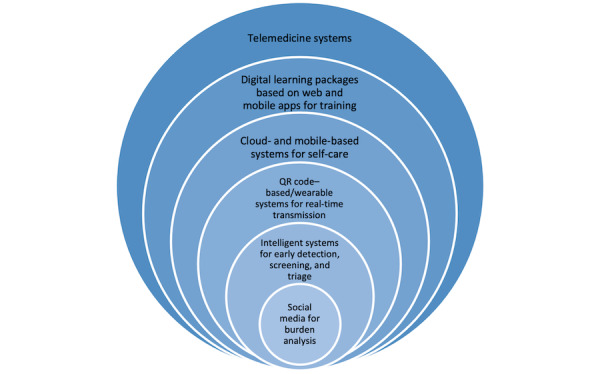

Telemedicine systems are highly used in many countries. In European countries, tracking of patients was adopted due to its feasibility in smaller countries; also, home care and self-care receive a relatively large amount of focus in these countries. Intelligent systems, CDSSs, and intelligent triage systems are not well adopted due to the need to supply them with data. These data are being gathered worldwide. Furthermore, analysis of social health data could be interesting, although little research has been done in this regard. Figure 1 shows the extent of the technologies developed for fighting the COVID-19 pandemic in the literature.

Figure 1.

Technologies currently being applied to address the COVID-19 pandemic. QR: quick response.

Overall, in the studied countries, after the alarm was raised regarding the pandemic, implementation of eHealth strategies began immediately. mHealth solutions and large-scale deployment of virtual consultations were launched. Data analysis approaches are being applied to support decision makers, and websites and electronic training tools are being used to improve patients’ protective behaviors. Although this study presents digital tools that are being applied for pandemic control in general, it lacks evaluation of the exact outcomes of using these digital health tools; thus, further studies are needed to evaluate the effects and outcomes of using digital health tools. This study could help health policy makers make decisions regarding the investment of these tools to control COVID-19.

Conclusion

This study reviewed the digital health tools to fight COVID-19 that have been reported in the 10 countries in which the disease is most prevalent. Although there is no equal strategy to apply digital health tools across the affected countries for pandemic control, these tools are among the primary policies that governmental and private companies have considered for disease control. The United States has developed the most technologies to fight the pandemic. Furthermore, China, the first country that was affected by COVID-19, has applied a great number of digital tools, such as epidemiological indicators, analysis platforms, drones, robots, mobile apps, training websites and educational media, videoconferencing, smart infection detectors, intelligent patient tracers, and telemedicine systems. Having considered the potential of available information technologies worldwide in the 21st century, particularly in developed countries, it appears that more digital health products, especially intelligent products, remain to be created and applied for the management of viral infections and other health crises.

Abbreviations

- CDSS

clinical decision support system

- GIS

geographic information system

- mHealth

mobile health

- NHS

National Health Service

- QR

quick response

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, Zhao X, Huang B, Shi W, Lu R, Niu P, Zhan F, Ma X, Wang D, Xu W, Wu G, Gao GF, Tan W. A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020 Feb 20;382(8):727–733. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Responding to community spread of COVID-19: interim guidance. World Health Organization. [2021-03-04]. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331421/WHO-COVID-19-Community_Transmission-2020.1-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- 3.Guan W, Ni Z, Hu Y, Liang W, Ou C, He J, Liu L, Shan H, Lei C, Hui DS, Du B, Li L, Zeng G, Yuen K, Chen R, Tang C, Wang T, Chen P, Xiang J, Li S, Wang J, Liang Z, Peng Y, Wei L, Liu Y, Hu Y, Peng P, Wang J, Liu J, Chen Z, Li G, Zheng Z, Qiu S, Luo J, Ye C, Zhu S, Zhong N. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020 Apr 30;382(18):1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atreja A, Gordon SM, Pollock DA, Olmsted RN, Brennan PJ, Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee Opportunities and challenges in utilizing electronic health records for infection surveillance, prevention, and control. Am J Infect Control. 2008 Apr;36(3 Suppl):S37–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2008.01.002. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/18374211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.NHS Digital. [2021-03-06]. https://digital.nhs.uk/

- 6.Bhavnani SP, Narula J, Sengupta PP. Mobile technology and the digitization of healthcare. Eur Heart J. 2016 May 07;37(18):1428–38. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv770. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/26873093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joshi AU, Randolph FT, Chang AM, Slovis BH, Rising KL, Sabonjian M, Sites FD, Hollander JE. Impact of emergency department tele-intake on left without being seen and throughput metrics. Acad Emerg Med. 2020 Feb 26;27(2):139–147. doi: 10.1111/acem.13890. doi: 10.1111/acem.13890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Langabeer J, Gonzalez M, Alqusairi D, Champagne-Langabeer T, Jackson A, Mikhail J, Persse D. Telehealth-enabled emergency medical services program reduces ambulance transport to urban emergency departments. West J Emerg Med. 2016 Nov;17(6):713–720. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2016.8.30660. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/27833678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hollander JE, Carr BG. Virtually perfect? Telemedicine for Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020 Apr 30;382(18):1679–1681. doi: 10.1056/nejmp2003539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lurie N, Carr BG. The role of telehealth in the medical response to disasters. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Jun 01;178(6):745–746. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dong E, Du H, Gardner L. An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020 May;20(5):533–534. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(20)30120-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reeves J, Hollandsworth H, Torriani F, Taplitz R, Abeles S, Tai-Seale M, Millen M, Clay B, Longhurst Christopher A. Rapid response to COVID-19: health informatics support for outbreak management in an academic health system. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020 Jun 01;27(6):853–859. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocaa037. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32208481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scott BK, Miller GT, Fonda SJ, Yeaw RE, Gaudaen JC, Pavliscsak HH, Quinn MT, Pamplin JC. Advanced digital health technologies for COVID-19 and future emergencies. Telemed J E Health. 2020 Oct 01;26(10):1226–1233. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2020.0140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bayram M, Springer S, Garvey CK, Özdemir Vural. COVID-19 digital health innovation policy: a portal to alternative futures in the making. OMICS. 2020 Aug 01;24(8):460–469. doi: 10.1089/omi.2020.0089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Torous J, Jän Myrick Keris, Rauseo-Ricupero N, Firth J. Digital mental health and COVID-19: using technology today to accelerate the curve on access and quality tomorrow. JMIR Ment Health. 2020 Mar 26;7(3):e18848. doi: 10.2196/18848. https://mental.jmir.org/2020/3/e18848/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Calton B, Abedini N, Fratkin M. Telemedicine in the time of coronavirus. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020 Jul;60(1):e12–e14. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.03.019. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32240756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moazzami B, Razavi-Khorasani N, Dooghaie Moghadam A, Farokhi E, Rezaei N. COVID-19 and telemedicine: Immediate action required for maintaining healthcare providers well-being. J Clin Virol. 2020 May;126:104345. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104345. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32278298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keesara S, Jonas A, Schulman Kevin. Covid-19 and health care's digital revolution. N Engl J Med. 2020 Jun 04;382(23):e82. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2005835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alwashmi MF. The use of digital health in the detection and management of COVID-19. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 Apr 23;17(8):2906. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17082906. https://www.mdpi.com/resolver?pii=ijerph17082906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fagherazzi G, Goetzinger C, Rashid M, Aguayo G, Huiart Laetitia. Digital health strategies to fight COVID-19 worldwide: challenges, recommendations, and a call for papers. J Med Internet Res. 2020 Jun 16;22(6):e19284. doi: 10.2196/19284. https://www.jmir.org/2020/6/e19284/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sarbadhikari S, Sarbadhikari S. The global experience of digital health interventions in COVID-19 management. Indian J Public Health. 2020;64(6):117. doi: 10.4103/ijph.ijph_457_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic. Worldometer. [2021-03-04]. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/

- 23.Kamel Boulos MN, Geraghty EM. Geographical tracking and mapping of coronavirus disease COVID-19/severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) epidemic and associated events around the world: how 21st century GIS technologies are supporting the global fight against outbreaks and epidemics. Int J Health Geogr. 2020 Mar 11;19(1):8. doi: 10.1186/s12942-020-00202-8. https://ij-healthgeographics.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12942-020-00202-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang Yang, Zhou Yin, Liu Xiaoqiang, Tan Jianguo. Health services provision of 48 public tertiary dental hospitals during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Clin Oral Investig. 2020 May;24(5):1861–1864. doi: 10.1007/s00784-020-03267-8. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32246280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meng L, Qiu F, Sun S. Providing pharmacy services at cabin hospitals at the coronavirus epicenter in China. Int J Clin Pharm. 2020 Apr 2;42(2):305–308. doi: 10.1007/s11096-020-01020-5. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32240484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ohannessian R, Duong TA, Odone A. Global telemedicine implementation and integration within health systems to fight the COVID-19 Pandemic: a call to action. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020 Apr 02;6(2):e18810. doi: 10.2196/18810. https://publichealth.jmir.org/2020/2/e18810/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pan X, Ojcius David M, Gao Tianyue, Li Zhongsheng, Pan Chunhua, Pan Chungen. Lessons learned from the 2019-nCoV epidemic on prevention of future infectious diseases. Microbes Infect. 2020 Mar 27;22(2):86–91. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2020.02.004. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32088333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pan X. Application of personal-oriented digital technology in preventing transmission of COVID-19, China. Ir J Med Sci. 2020 Nov 27;189(4):1145–1146. doi: 10.1007/s11845-020-02215-5. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32219674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun Q, Qiu H, Huang M, Yang Y. Lower mortality of COVID-19 by early recognition and intervention: experience from Jiangsu Province. Ann Intensive Care. 2020 Mar 18;10(1):33. doi: 10.1186/s13613-020-00650-2. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32189136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hernández-García Ignacio, Giménez-Júlvez Teresa. Assessment of health information about COVID-19 prevention on the internet: infodemiological study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020 Apr 01;6(2):e18717. doi: 10.2196/18717. https://publichealth.jmir.org/2020/2/e18717/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hua J, Shaw R. Corona virus (COVID-19) "infodemic" and emerging issues through a data lens: the case of China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 Mar 30;17(7):2309. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17072309. https://www.mdpi.com/resolver?pii=ijerph17072309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Drew DA, Nguyen LH, Steves CJ, Menni C, Freydin M, Varsavsky T, Sudre CH, Cardoso MJ, Ourselin S, Wolf J, Spector TD, Chan AT, COPE Consortium Rapid implementation of mobile technology for real-time epidemiology of COVID-19. Science. 2020 Jun 19;368(6497):1362–1367. doi: 10.1126/science.abc0473. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32371477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Franco D, Montenegro T, Gonzalez GA, Hines K, Mahtabfar A, Helgeson MD, Patel R, Harrop J. Telemedicine for the spine surgeon in the age of COVID-19: multicenter experiences of feasibility and implementation strategies. Global Spine J. 2020 Jun 03;:2192568220932168. doi: 10.1177/2192568220932168. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/2192568220932168?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%3dpubmed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gilbert AW, Billany JCT, Adam R, Martin L, Tobin R, Bagdai S, Galvin N, Farr I, Allain A, Davies L, Bateson J. Rapid implementation of virtual clinics due to COVID-19: report and early evaluation of a quality improvement initiative. BMJ Open Qual. 2020 May 21;9(2):e000985. doi: 10.1136/bmjoq-2020-000985. https://bmjopenquality.bmj.com/lookup/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=32439740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Giudice A, Barone S, Muraca D, Averta F, Diodati F, Antonelli A, Fortunato L. Can teledentistry improve the monitoring of patients during the Covid-19 dissemination? A descriptive pilot study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 May 13;17(10):3399. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17103399. https://www.mdpi.com/resolver?pii=ijerph17103399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gong K, Xu Z, Cai Z, Chen Y, Wang Z. Internet hospitals help prevent and control the epidemic of COVID-19 in China: multicenter user profiling Study. J Med Internet Res. 2020 Apr 14;22(4):e18908. doi: 10.2196/18908. https://www.jmir.org/2020/4/e18908/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gong M, Liu L, Sun X, Yang Y, Wang S, Zhu H. Cloud-based system for effective surveillance and control of COVID-19: useful experiences from Hubei, China. J Med Internet Res. 2020 Apr 22;22(4):e18948. doi: 10.2196/18948. https://www.jmir.org/2020/4/e18948/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goodman-Casanova JM, Dura-Perez E, Guzman-Parra J, Cuesta-Vargas A, Mayoral-Cleries F. Telehealth home support during COVID-19 confinement for community-dwelling older adults with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia: survey study. J Med Internet Res. 2020 May 22;22(5):e19434. doi: 10.2196/19434. https://www.jmir.org/2020/5/e19434/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grange ES, Neil EJ, Stoffel M, Singh AP, Tseng E, Resco-Summers K, Fellner BJ, Lynch JB, Mathias PC, Mauritz-Miller K, Sutton PR, Leu MG. Responding to COVID-19: The UW Medicine Information Technology Services Experience. Appl Clin Inform. 2020 Mar 08;11(2):265–275. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1709715. http://www.thieme-connect.com/DOI/DOI?10.1055/s-0040-1709715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grenda T, Whang S, Evans N. Transitioning a surgery practice to telehealth during COVID-19. Ann Surg. 2020 Aug;272(2):e168–e169. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004008. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32675529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grossman SN, Han SC, Balcer LJ, Kurzweil A, Weinberg H, Galetta SL, Busis NA. Rapid implementation of virtual neurology in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Neurology. 2020 Jun 16;94(24):1077–1087. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hames JL, Bell DJ, Perez-Lima LM, Holm-Denoma JM, Rooney T, Charles NE, Thompson SM, Mehlenbeck RS, Tawfik SH, Fondacaro KM, Simmons KT, Hoersting RC. Navigating uncharted waters: considerations for training clinics in the rapid transition to telepsychology and telesupervision during COVID-19. J Psychother Integr. 2020 Jun;30(2):348–365. doi: 10.1037/int0000224. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hanna MG, Reuter VE, Ardon O, Kim D, Sirintrapun SJ, Schüffler Peter J, Busam KJ, Sauter JL, Brogi E, Tan LK, Xu B, Bale T, Agaram NP, Tang LH, Ellenson LH, Philip J, Corsale L, Stamelos E, Friedlander MA, Ntiamoah P, Labasin M, England C, Klimstra DS, Hameed M. Validation of a digital pathology system including remote review during the COVID-19 pandemic. Mod Pathol. 2020 Nov 22;33(11):2115–2127. doi: 10.1038/s41379-020-0601-5. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32572154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hom MA, Weiss RB, Millman ZB, Christensen K, Lewis EJ, Cho S, Yoon S, Meyer NA, Kosiba JD, Shavit E, Schrock MD, Levendusky PG, Björgvinsson T. Development of a virtual partial hospital program for an acute psychiatric population: Lessons learned and future directions for telepsychotherapy. J Psychother Integr. 2020 Jun;30(2):366–382. doi: 10.1037/int0000212. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Itamura K, Rimell FL, Illing EA, Higgins TS, Ting JY, Lee MK, Wu AW. Assessment of patient experiences in otolaryngology virtual visits during the COVID-19 pandemic. OTO Open. 2020 Jun 08;4(2):2473974X2093357. doi: 10.1177/2473974x20933573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Judson T, Odisho A, Neinstein A, Chao J, Williams A, Miller C, Moriarty T, Gleason N, Intinarelli G, Gonzales Ralph. Rapid design and implementation of an integrated patient self-triage and self-scheduling tool for COVID-19. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020 Jun 01;27(6):860–866. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocaa051. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32267928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu G, Yang P, Xie Y, Woodruff HC, Rao X, Guiot J, Frix A, Louis R, Moutschen M, Li J, Li J, Yan C, Du D, Zhao S, Ding Y, Liu B, Sun W, Albarello F, D'Abramo A, Schininà Vincenzo, Nicastri E, Occhipinti M, Barisione G, Barisione E, Halilaj I, Lovinfosse P, Wang X, Wu J, Lambin P. Development of a clinical decision support system for severity risk prediction and triage of COVID-19 patients at hospital admission: an international multicentre study. Eur Respir J. 2020 Aug 02;56(2):2001104. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01104-2020. http://erj.ersjournals.com:4040/lookup/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=32616597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang S, Ding S, Xiong L. A new system for surveillance and digital contact tracing for COVID-19: spatiotemporal reporting over network and GPS. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2020 Jun 10;8(6):e19457. doi: 10.2196/19457. https://mhealth.jmir.org/2020/6/e19457/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Timmers T, Janssen L, Stohr J, Murk J, Berrevoets MAH. Using eHealth to support COVID-19 education, self-assessment, and symptom monitoring in the Netherlands: observational study. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2020 Jun 23;8(6):e19822. doi: 10.2196/19822. https://mhealth.jmir.org/2020/6/e19822/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pépin Jean Louis, Bruno RM, Yang R, Vercamer V, Jouhaud P, Escourrou P, Boutouyrie P. Wearable activity trackers for monitoring adherence to home confinement during the COVID-19 pandemic worldwide: data aggregation and analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2020 Jun 19;22(6):e19787. doi: 10.2196/19787. https://www.jmir.org/2020/6/e19787/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rabuñal Ramón, Suarez-Gil R, Golpe R, Martínez-García Mónica, Gómez-Méndez Raquel, Romay-Lema E, Pérez-López Antía, Rodríguez-Álvarez Ana, Bal-Alvaredo M. Usefulness of a telemedicine tool TELEA in the management of the COVID-19 pandemic. Telemed J E Health. 2020 Nov 01;26(11):1332–1335. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2020.0144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cheng P, Xia G, Pang P, Wu B, Jiang W, Li Y, Wang M, Ling Q, Chang X, Wang J, Dai X, Lin X, Bi X. COVID-19 epidemic peer support and crisis intervention via social media. Community Ment Health J. 2020 Jul 6;56(5):786–792. doi: 10.1007/s10597-020-00624-5. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32378126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Castaldi S, Maffeo M, Rivieccio B, Zignani M, Manzi G, Nicolussi F, Salini S, Micheletti A, Gaito S, Biganzoli Elia. Monitoring emergency calls and social networks for COVID-19 surveillance. To learn for the future: the outbreak experience of the Lombardia region in Italy. Acta Biomed. 2020 Jul 20;91(9-S):29–33. doi: 10.23750/abm.v91i9-S.10038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Blake H, Bermingham F, Johnson G, Tabner A. Mitigating the psychological impact of COVID-19 on healthcare workers: a digital learning package. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 Apr 26;17(9):2997. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17092997. https://www.mdpi.com/resolver?pii=ijerph17092997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Guo Y, Cao Q, Hong Z, Tan Y, Chen S, Jin H, Tan K, Wang D, Yan Y. The origin, transmission and clinical therapies on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak - an update on the status. Mil Med Res. 2020 Mar 13;7(1):11. doi: 10.1186/s40779-020-00240-0. https://mmrjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40779-020-00240-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ayyoubzadeh S, Ayyoubzadeh S, Zahedi H, Ahmadi M, R Niakan Kalhori Sharareh. Predicting COVID-19 incidence through analysis of Google Trends data in Iran: data mining and deep learning pilot study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020 Apr 14;6(2):e18828. doi: 10.2196/18828. https://publichealth.jmir.org/2020/2/e18828/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Qiang X, Xu P, Fang G, Liu W, Kou Z. Using the spike protein feature to predict infection risk and monitor the evolutionary dynamic of coronavirus. Infect Dis Poverty. 2020 Mar 25;9(1):33. doi: 10.1186/s40249-020-00649-8. https://idpjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40249-020-00649-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Verity R, Okell LC, Dorigatti I, Winskill P, Whittaker C, Imai N, Cuomo-Dannenburg G, Thompson H, Walker PGT, Fu H, Dighe A, Griffin JT, Baguelin M, Bhatia S, Boonyasiri A, Cori A, Cucunubá Z, FitzJohn R, Gaythorpe K, Green W, Hamlet A, Hinsley W, Laydon D, Nedjati-Gilani G, Riley S, van Elsland S, Volz E, Wang H, Wang Y, Xi X, Donnelly CA, Ghani AC, Ferguson NM. Estimates of the severity of coronavirus disease 2019: a model-based analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020 Jun;20(6):669–677. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(20)30243-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wu J, Leung K, Leung Gm. Nowcasting and forecasting the potential domestic and international spread of the 2019-nCoV outbreak originating in Wuhan, China: a modelling study. Lancet. 2020 Feb;395(10225):689–697. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30260-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Santillana M, Nguyen AT, Dredze M, Paul MJ, Nsoesie EO, Brownstein JS. Combining search, social media, and traditional data sources to improve influenza surveillance. PLoS Comput Biol. 2015 Oct 29;11(10):e1004513. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004513. https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.McGough SF, Brownstein JS, Hawkins JB, Santillana M. Forecasting Zika incidence in the 2016 Latin America outbreak combining traditional disease surveillance with search, social media, and news report data. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017 Jan 13;11(1):e0005295. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Majumder MS, Santillana M, Mekaru SR, McGinnis DP, Khan K, Brownstein JS. Utilizing nontraditional data sources for near real-time estimation of transmission dynamics during the 2015-2016 Colombian Zika virus disease outbreak. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2016 Jun 01;2(1):e30. doi: 10.2196/publichealth.5814. https://publichealth.jmir.org/2016/1/e30/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Serper M, Cubell AW, Deleener ME, Casher TK, Rosenberg DJ, Whitebloom D, Rosin RM. Telemedicine in liver disease and beyond: can the COVID-19 crisis lead to action? Hepatology. 2020 Aug 25;72(2):723–728. doi: 10.1002/hep.31276. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32275784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wilson ME. What goes on board aircraft? Passengers include Aedes, Anopheles, 2019-nCoV, dengue, Salmonella, Zika, et al. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020;33:101572. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101572. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32035269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Krishna S, Boren SA, Balas EA. Healthcare via cell phones: a systematic review. Telemed J E Health. 2009 Apr;15(3):231–40. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2008.0099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jibb LA, Cafazzo JA, Nathan PC, Seto E, Stevens BJ, Nguyen C, Stinson JN. Development of a mHealth real-time pain self-management app for adolescents with cancer: an iterative usability testing study. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2017 Apr 04;34(4):283–294. doi: 10.1177/1043454217697022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kim H, Lee H, Park JI, Choi CH, Park S, Kim HJ, Kim YS, Ye S. Smartphone application for mechanical quality assurance of medical linear accelerators. Phys Med Biol. 2017 Jun 07;62(11):N257–N270. doi: 10.1088/1361-6560/aa67d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wong D. How Can Foreign Technology Investors Benefit from China’s New Infrastructure Plan? China Briefing. 2020. Aug 07, [2021-03-04]. https://www.china-briefing.com/news/how-foreign-technology-investors-benefit-from-chinas-new-infrastructure-plan/

- 69.The Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) European Commission. [2021-03-08]. https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/digital-economy-and-society-index-desi.

- 70.Guerrini F. How the coronavirus is forcing Italy to become a digital country, at last. Forbes. 2020. Mar 14, [2021-03-04]. https://www.forbes.com/sites/federicoguerrini/2020/03/14/how-the-coronavirus-is-forcing-italy-to-become-a-digital-country-at-last/?sh=649ae9376f75.

- 71.Vega G. Spain launches first phase of coronavirus-tracking app. El País. 2020. Jun 29, [2021-03-04]. https://english.elpais.com/society/2020-06-29/spain-launches-first-phase-of-coronavirus-tracking-app.html.

- 72.Coronavirus (COVID-19) US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Federal Emergency Management Agency. [2021-03-06]. https://www.coronavirus.gov/

- 73.COVID-19. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; [2021-03-06]. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Thompson R. StopCOVID: France's controversial tracing app ready by June. Euronews. 2020. May 05, [2021-03-04]. https://www.euronews.com/2020/04/29/coronavirus-french-mps-approve-covid-19-tracing-app-despite-privacy-concerns.

- 75.NHS Digital COVID-19 Update. NHS Digital. 2020. Apr 30, [2021-03-06]. https://digital.nhs.uk/binaries/content/assets/website-assets/coronavirus/nhs-digital-covid-19-update-april-2020.pdf.

- 76.New corona screening and care (COVID-19) Iran Ministry of Health and Medical Education. [2021-03-06]. https://salamat.gov.ir/

- 77.How the Dutch are responding to coronavirus with digital healthcare. Invest in Holland. 2020. May 01, [2021-03-04]. https://investinholland.com/news/how-dutch-have-responded-digitally-corona-crisis/#:~:text=Pharos%20responded%20to%20this%20challenge,joint%2Dcooperation%20with%20other%20parties.&text=In%20the%20Netherlands%2C%20the%20Dutch,step%20up%20innovative%20eHealth%20solutions.

- 78.How Germany leveraged digital health to combat COVID-19. The Medical Futurist. 2020. Apr 09, [2021-03-04]. https://medicalfuturist.com/how-germany-leveraged-digital-health-to-combat-covid-19/